Copyright 2022 by Leland Quarterly | All Rights Reserved Stanford University | Giant Horse Printing, San Francisco

EDITORS IN CHIEF Jordan Pollock Angela Yang

Adriana Carter Kavya Srikanth

POETRY EDITORS Lucy Chae Callum Tresnan

Allison Argueta Matias Benitez Lishan Carroll Viva Donohoe Kyla Figueroa Shannon Gifford Anna Kiesewetter Ben Marra Malia Maxwell Divya Mehrish Kristie Park Nicole Segaran Cassie Shaw Pann Sripitak Katherine Wong Julia Wortman

BOARD MEMBERS Olivia Manes Lily Nilipour Linda Ye

“Move slowly. Move more slowly than you think you need to, and that will be the right pace.”

If nothing else, let this be a note of permission to move slowly.

At Stanford, so much of our self-worth rests on how quickly we can accomplish difficult tasks, from grinding out a final paper before Green Library closes to coding the newest social media app and becoming the next Evan Spiegel. But in this issue of LQ, we want to recognize the slow work that each and every one of us does as we figure out how to exist in this rapidly unraveling rat-race—especially this past quarter as we grieved heartbreaking losses, leaned on each other for support, and learned to heal through rest, reflection, and creation.

The stories, poems, and visual art featured in this issue reveal the importance of moving slowly in order to see clearly and feel deeply. In this issue, we lift the skirt to reveal scratches and scars. We burrow into moments of doubt during familiar rituals. We examine the cyclic patterns of heartbreak under the ebbs and flows of moonlit waves. We explore a hometown’s complex relationship with tradition and modernity through a loving camera lens.

The making of this issue was an ode to slow work as well. We feel immensely grateful for the contributors, for their patience and perseverance through multiple rounds of editing. We truly appreciate our team of editors, who attended week after week of meetings to read, review, deliberate, and advocate for the many beautiful pieces we have received. And finally, we extend our thanks to you, the reader, who has taken the time, wherever you are, to pause from your day and flip through these pages. We hope you’ll find something that resonates, that slows you down a little, and holds you in whatever way you need.

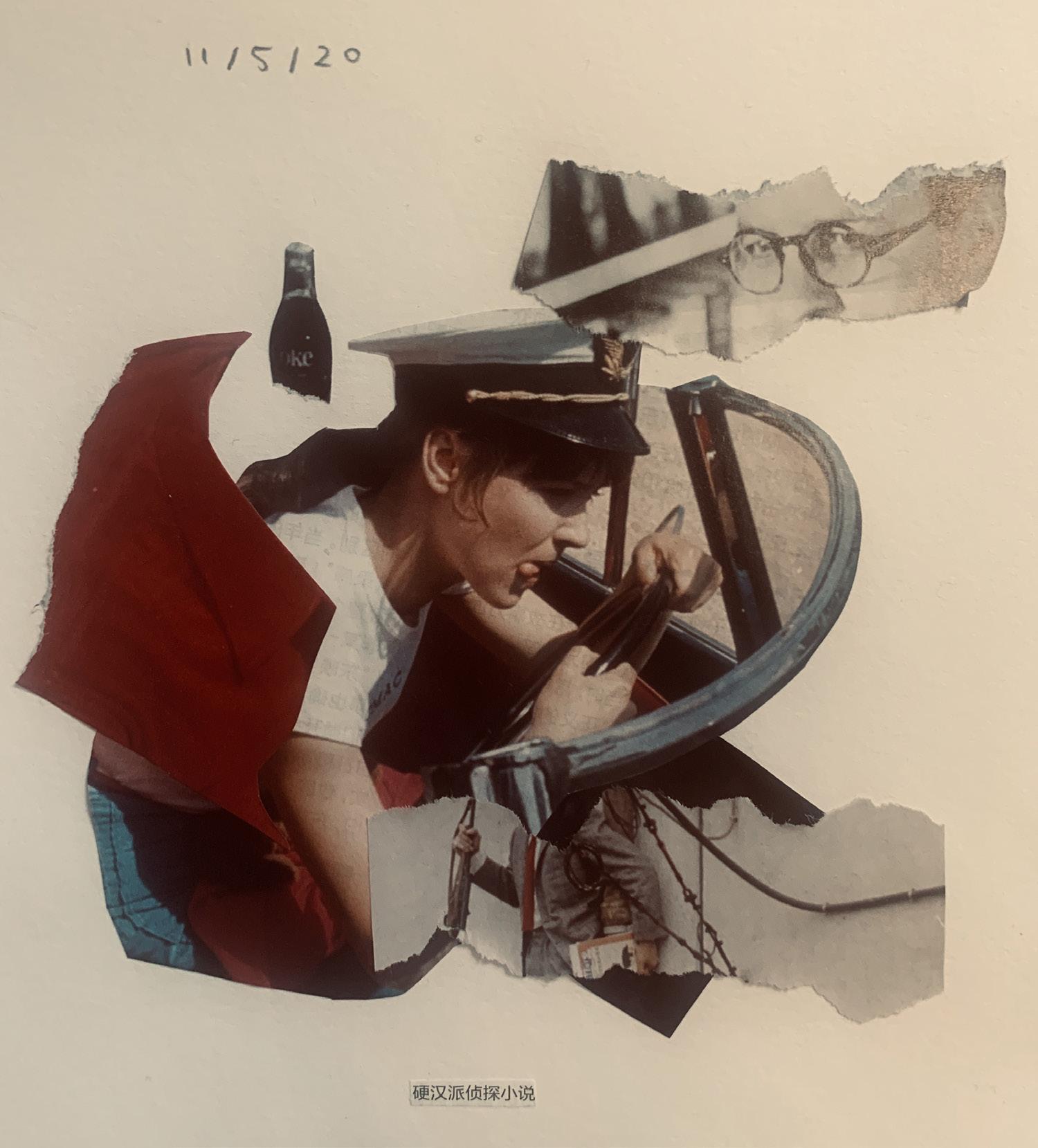

Jordan Pollock and Angela Yang, Editors-in-ChiefAs a photographer, I am interested in exploring China’s contemporary economy and its impact on the young generation. I am continuously inspired by the paradoxical presence of popular culture elements mixed with our mundane lives. My ongoing project, A Hundred Stories, is an exploration of this interest through digitally manipulated images and documentary photography. I collaged QR codes and the popular western clothing brand Burberry to describe the strange dichotomies of our generations torn apart from the old and the global. The silent wind of time has continued to blow. The process brought me a strange feeling of satisfaction, which only a hundred stories can reveal.

Michelle Sijia Ma, Cover ArtistMorris Louis’s Pendulum, Surya Hendry 10 Shiners, Isabelle Claire Edgar 20 Francis, Isabella Saracco 28 At least I got to spend your birthday with you, Connor Lane 41 natural disaster, Anna Keiswetter 42 bump! bump! bump! Chaidie Petris 43 ode to grapes, Aden McCracken 44 ode to idaho olive garden, Jennifer Co 46 Remembrance for a Crab, Elizabeth Grant 47 Sukiyaki Dinner, Leah Arima Chase 66 Postnatal, Yasi Khan 68

Leland Quarterly | Winter 2022

Tashlich, Danny Ritz 16 Holiday, Danny Ritz 18 The Bird Eaters, Anna Zheng 22 What do we do when love leaves through the door and into the night? Cole Dill-de Sa 33 Oskar & Allie, Adam Chin 48

Hide and Seek, Hannah Cha 11 Clout Chaser, Hannah Cha 12 Gratitude, Hannah Cha 13 Find the Light, Hannah Cha 14 Crushed, Hannah Cha 15 Hard-Boiled, Alice Fang 21 Tiburon, Nur Shelton 30 Tetons, Cathy Gao 32 Bleeding Cavity, Aden McCracken 45 Alpine Time, Nur Shelton 65 Sukiyaki Dinner, Leah Arima Chase 67 Scan it!, Michelle Sijia Ma 69 Desire, Michelle Sijia Ma 70 Portrait of Qinglian, Michelle Sijian Ma 71

Last night, you cut tomatoes with the dull knife and it slipped into your knuckle. Your brief gasp, tang finding blood, undone flesh, a scent of ripeness. Here is that moment, flowing across canvas. A wound unfolding

Find the Light (left) emphasizes the importance of communal support in the midst of a pandemic, where empathy and consideration for others are vital for the safety of others despite physical barriers between people. It also emphasizes hope; the fingers in the shadow are crossed, which means hope in British sign language, but also for the need to have a hopeful and wishful mindset within hard times.

The bag I’ll soon use to pick up the Bear’s shit is, for now, full of my sins. I’m standing on a bridge beneath a beautiful forest, tearing apart pieces of bread and forgetting as I toss them into the river below. It’s me, my father and mother, our sheepdog (the Bear, I call her), and one third of my three older brothers, which is to say— my brother. We’ve been here before, in this sacred place, on this sacred day, though usually at a different part of the stream.

Oh, right. It’s a stream. In my head it was always a river, but through my eyes now as I see it, it is most certainly a stream. The action itself, a ritual of the Jewish New Year, feels quite loud, though in this place we cannot hear a sound, save for the gentle landing of fallen, forgotten bread on the water below.

I don’t know the point at which memory became an act of atonement, but I cherish the irony of my forgetting. As the year renews, we’re to cast our sins into water with pebbles (or, in my family’s case, crumbs of pita bread) and hopefully renew ourselves in tow. Yet in my head the day was always for remembering. I usually get through this part rather quickly, but today, under these trees, with this defrosting pita in my hand, I feel like the pebbles I should’ve been using, sinking at the surface of the water. So, I just rip and remember.

The glutens release as we tear. The Bear is stepping on leaves behind me, climbing on her hind legs to look out over the bridge. When she stands up, we don’t look so different. This morning I was jealous of her. Jealous when my parents called her the baby of the family. Jealous when my brother, the same one dropping his sins to my right, cradled her for what felt like hours before acknowledging me. I hope she does not know how I feel. I drop another piece.

As it falls, my brother and father walk away—they’ve finished atoning, and the Bear has to go make. I stare at my brother’s body as he walks: shoulders widened by years in the pool, neck long like mine, legs long and thick like a redwood, yet so small and delicate by the achilles. I imagine what it must feel like to become it, that delicate tendon, connecting his feet and his legs, holding the whole system together, veins flexing and tightening around the whole of my body like vines. A few crumbs slip out from my fingers, this time towards the right.

As they disappear into the water, I feel my mother’s eyes turn onto me. What must she see as she sees me here, slower than the rest, walled within my memories? We are nearly identical, perhaps the most so of any two in my family. By instinct, I crave forgiveness. For what? The pace of my remembering? I close my eyes to think, as though thoughts can be unthought, actions undone. Suddenly her hand on my shoulder grows into an embrace. The sound of her breath in my ear reopens my eyes. I wrap my arms around her in return. My chin fits perfectly into her collarbone, our bodies again, for a moment, one.

I drop the last bit of pita out of my hand. It misses the water, lands on a rock jutting out from the stream, daring every passerby to question its existence. Be like the bread, I hear her say, though in words she says nothing at all.

Behind us, the Bear is having trouble making, so we let go of each other. My brother and father call us over quickly, they need a bag. We stuff our hands into our pockets, worry as we do so much with the dog we love so dearly, realize we are bagless. I pull the pita bag from my pocket, and as though on cue, the Bear goes. A sigh like relief from all. My father compares their shape to a sausage link to my brother as my mother and I walk over. I reach into the bag. Bits of defrosted pita water cling to its walls like teardrops. Standing with my family—my mother and father, the Bear, and a third of my brothers—I wipe them dry, and pick up what must be carried.

It is here in this photo, in the center of her lens, directly in front of her eyes, that you first realize how much the two of you look alike. You’ll joke about this for the duration of the affair, say perhaps we are really cousins, laughing at the grotesque shapes of your inbred and unborn children. Secretly, at the back of your heart, you will think it no laughing matter. Instead, you will believe with every muscle in your body that you, like explorers of earth and space, inventors of fire and light, or the sun and moon themsleves, discovered an unknown and unbreakable sameness in each other that not even the unraveling of the world could disrupt.

Recognize the dimples in your cheeks. How they hold up your smile like a bridge, making roads over water, making the impossible real. Feel like a painting. That’s how your skin looks in the picture—the oils popping out from the canvas into your pores. No, feel like a Turner painting. Feel the oranges and unforeseen yellows, the impossible until suddenly obvious purples. Remember how she seemed that way once, too. Do you see the landscape that has become of your chest? You think I mean the hair that covers it, but I am referring to a heart that has grown inside of it.

Catch the bit of sandwich wedged between your front and canine teeth, an eggplant cutlet on a Dutch Crunch roll. Do as you did then: notice your mouth ever-so-suddenly wet. Ignore the drops of saliva in your lap, hope she does not see them. Imagine her thinking they are for her. What will you say when she asks? When she asked you before, you laughed, the fear inside blossomed into color. Then she did too in response, and the chorus that you made with your laughter is what made the blur in the top right corner of the photo. Part of the image has to blur, has to fade, obscure into

meaninglessness. We do not exist without our ceasing. It was the last roll of Dutch Crunch they were serving that day, so you split the sandwich with her. In each other’s arms (as you are in the photo), strands of lettuce and tomato spilling out between you, you become eyes in the act of blinking, seeking whatever colors can be seen before you close yourselves back into darkness.

Soon, the rest of the image will blur, or perhaps the opposite— the image itself will come to surround all that was of the memory. Until then, remember what remains of the day. The sandwich, the girl on the other side of the sandwich that was the same as you, and the roundfaced man on the other side of the sandwich-shop counter who noticed everything:

the grimace you shared as you handed him the cash, a grimace that soon would grace every human contact, every social interaction in the world

thanking him for the free lollipop (a tradition of this store) when he tells you that your friend is beautiful, or rather (correcting himself) that he sees how beautiful she is from watching you look at her

that while all this was happening she was on the phone talking to and thinking about someone else entirely that even long after you stop speaking to her in the flesh, on facetime and the phone, well still sometimes the phone but it isn’t the same, not as it was when you thought you were one, when your eyes were still open together, you still at one point saw each other in that kind of way.

That while she was on the phone and you were talking to the sandwich man, you couldn’t stop staring at each other.

For the duration of the affair, you often joked that the two of you had built a ‘Hanukkah relationship,’ insomuch that the candle was supposed to have stayed lit for a single night, but instead managed 8 whole nights. Hence, a holiday.

When you finally return to the shop 18 months later to find it shuttered, boarded up, and empty, wish that you could tell her how it really was the last roll.

You said it’d be sexy if I drowned. A dark lip. The last oval button undone. And when you point a flashlight on the shoreline the shiners jump like you’ve boiled the water beneath their bellies and you grab one, mid air and put it in your pocket, silver and cold with your keys, for me to find later.

We were sitting on the floor and you shook out your hair for dandruff or fog and I wondered if everyone is a little bit perverse. In some way. A dream of storing an eyelash or a hangnail beneath the floorboards. You trace the ridge of my collarbone with your fingertip and then fall asleep.

I don’t set alarms because of the clock with red lettering that woke me to a radio report of the eighteen year abduction of the girl with the butterfly ring. I was born with a strawberry birthmark above my left ear and everyone thought I was bleeding. I don’t know why it disappeared.

I pretend to be on the phone when I walk up those stairs that connect the sidewalks where the lights don’t shine. I say I know, I know and so my achilles doesn’t get slit and added to the rubber band ball, you know, become inelasticated, I shine a light under the car, before stepping close enough to sit down and unbutton my coat and drive home in the fog.

Anna Zheng

The birds didn’t go down south that year. At first, we thought it might just be the heat. Then August went, and we said it was a late migration. September, maybe the hurricanes on the coast. By October, another flock of three hundred blackbirds had arrived in town, and none of them seemed in any hurry to leave. That’s when we knew they were staying.

The year the birds landed in Redstone was the same year as the July drought that left the crops parched in the fields and the river a muddy trickle. We were already bracing for a hard winter when the birds arrived to eat anything that was left. That Saturday, the synagogue was packed. Sunday, the church pews were overflowing. Monday, we had the first full-attendance town meeting in the history of Redstone. We prayed, we argued, we cursed, and every time we looked outside, we could feel the coming emptiness in our stomachs. The only person who was happy those hot, dry days was Old Stevie Wasserman.

Old Stevie had been an ornithologist before everything went sideways. Now, he was just another farmer, except for his tendency to stare into the distance when you spoke to him. We excused his peculiarities because he had the best binoculars in town. Those of us young enough remembered him visiting us at school with those binoculars. We would hike through the park, and he’d point to a shrub. “Look, there’s an Ovenbird in there, and a Northern Parula on the tree behind it.” Only after everyone had looked at both would he let us take turns gazing past the fence with his binoculars. We would stare at the dry horizon and try to match the yellow landscape with the stories the oldest townspeople had told us about cars and motorcycles that could drive far, far away.

But only for a minute. Old Stevie would spot another bird and run off after it, binoculars and us in tow.

Apart from the meetings, where he sat near the back and looked out the window, Old Stevie spent all of that fall outdoors, staring through his binoculars at all the birds. When someone reminded him we would starve because of his darn birds, he would smile a little smile and shrug. “Isn’t it beautiful?” he’d say. As the month wore on, that smile became more and more unbearable. We avoided him, and those who couldn’t were infected with his madness. Timmy burst into tears, Will almost punched him, and even dear, sweet Auntie Annie cursed him out. Eventually, we sent the Mayor down from his mansion to talk to him. The Mayor spoke of morale, of town duty. He asked him to lend his expertise to solving This Bird Problem, and, for God’s sake, to stop standing around staring at birds. When the Mayor ran out of steam, Old Stevie lowered his binoculars to look at him. He smiled. “I’ve seen God,” he told the Mayor. Redstone Nondenominational Church kicked him out after that, but he went right on staring through his binoculars. Needless to say, we all hated him a bit.

Nobody really knows who first had the idea of eating the birds, but it was probably Granny Harriet. Lucas and Young Nicole both like to say it was them, but everyone knows Lucas has no sense and Nicole was too busy kissing Tommy Jenkins to do anything of the sort. It was after the snows came. We weren’t starving yet, but everyone’s stores were growing thin. No one could buy potatoes for love or money, and everyone who owned a chicken or pig or cow had killed it weeks ago. Then, in early December, we woke to the smell of roasting meat, sizzling, fragrant fat from somewhere in town. And on the tail of that smell came Auntie Annie running down from her house up the hill.

“It’s bird,” she said. “Granny Eliot says someone is cooking a bird.”

So then we knew. We looked at our unwelcome visitors with new eyes, and faced with the choice between limp carrots or a

plump, juicy drumstick, we all became bird eaters overnight. There were vegetarians who threw up eating their first bird and learned to work their way up from sparrow-sized portions. There were religious nuts who found loopholes in their teachings, exempted butchering birds from their lists of sins. There were animal lovers, pacifists, toothless old timers; everyone wanted a part of the feast. The streets stank of blood and burnt feathers.

Only Old Stevie refused to eat. The first time he’d wandered into town and seen a bird killed, he’d spluttered, speechless. We glared preemptively and told him to stuff it, unless he wanted to leave for another village. He stuffed it. It was winter, and he wasn’t stupid—the next village we knew of was thirty miles away—but he didn’t come into the town proper again.

We would see him pacing outside his one-person shack, growing thinner by the day. His crop had fared even worse than most people’s. By early December, his meager stock of vegetables had run out. Age lines carved themselves around his sunken eyes. He retired to his shack and stopped pacing—there was no sense for a starving man to waste energy like that. But he still wouldn’t eat. By then, we could afford to be generous with him. It was midwinter, but with new ways of roasting birds, baking birds, sautéing birds, we were all reasonably plump and happy, and no one could quite remember why we hated poor Old Stevie. We brought him drumsticks, wings, anonymous, lumpy stews, but just as before, nothing moved him. Come Christmas, Granny Harriet brought him a whole roasted goose, only to be waved out of the shack without so much as a hello. When she knocked the day after, she found him collapsed on the floor.

We moved him to Granny Harriet’s living room, a shivering sack of bones, half-comatose. But Granny coaxed him back to life, heaping blankets on the couch, fetching hot water, spooning mouthfuls of bird broth into him. Three days in, he stopped shivering. When his exhaustion passed and the fever dreams began, she started him on solid meat.

Old Stevie’s head cleared in late January. When Granny Harriet came in and put his dinner on his lap, he recoiled.

“What is this?” He nudged the wing on his plate. “Why, bird meat, of course.”

He placed the plate on the floor, slightly pale. “I can’t eat this.”

“Don’t be silly. What else do you think you’ve been eating these past weeks?”

He retched. He tried to stand but fell back onto the couch. His foot caught the plate and it flew across the room and shattered. “Oh dear,” said Granny Harriet.

According to Granny, that was when he went crazy for the first time. He screamed and curled up, sobbing, thrashing around like a young child having a tantrum. That day, she didn’t dare get close, for fear of being hit. But he fell asleep readily enough, and the next day, he didn’t seem to remember anything that had happened.

We heard in town that Old Stevie had gone mad. The Mayor came straight from hunting to check on the town’s newest crackpot, on the concerns of the general community. At the door, Granny Harriet stopped him and tried to shove his newest kill out of sight. It was too late. Stevie had seen the bird. But he gazed vaguely at the Mayor and warbled, “What a lovely specimen of Northern Bobwhite! Look at its feathers!”

And for the first time, we realized the use of Old Stevie’s knowledge. We’d known that some of the small birds tasted better than the others, but now there was a more scientific way to go about it. We started listening to his rambling speeches, sought out his company. Even half-cracked, Old Stevie was everyone’s favorite those days. If you asked right, he could tell you the difference between an Ovenbird or a Northern Parula in fall plumage, or a female Ruby Throat and a male Rufous. But if someone mentioned eating, or he caught a glimpse of a recipe, or a songbird dressed and spitted—only Lucas was silly enough to bring a plucked bird with him—the mania would return. He’d scream and shake and scrabble

at the floorboards, as if trying to dig himself away. We would exit quietly and wait for him to settle, to erase what just happened from his mind. When he had reverted to his usual calm, we’d go back in and try again. We learned to say, “Old Stevie, I found this outside. What is it?” And he was delusional enough to believe it had died naturally.

By the end of winter, we all knew blackbird pie was overrated but worked just fine when no grouses could be found. If you were really unlucky, and all you could catch for dinner was a warbler, it was better to get an Ovenbird than a Northern Parula because they were fattier and fried well without any butter. And when their flour ran out, the Mayor’s family took to eating Rufous Hummingbirds for dessert, their spindly wings crystallized midflight in the last of the sugar.

Old Stevie ate too. As soon as he could walk, he moved back to his own shack, but Granny Harriet continued to cook for him. She would serve him birds drowned in sauce or chopped into little pieces. He never examined the dishes anymore, just downed the contents and thanked Granny for her excellent cooking. Then spring came. As the snow melted, we polished up the few birds remaining in town, and Old Stevie resumed his habitual window-watching, waiting for the spring migration. We knew better. Nothing went south, so nothing came back north. Day after day, the skies were quiet and empty. When the frost broke, Old Stevie didn’t bother planting crops. He was too busy staring out of his window, clutching his binoculars.

In May, he went over the edge. We’d seen him taking a walk that morning, searching the trees, but when Granny Harriet came by with dinner, he hadn’t come back. The town wasn’t large. By sundown, we’d found him, curled at the base of an old birch tree in the park, hugging his knees and rocking back and forth. “Flesh and bone,” he whimpered, “flesh and bone.” On the ground beside him were his binoculars. They were shattered. That was it for Old Stevie. No more periods of lucidity, no

almost-sane conversations. There was no question of poor, crazy Stevie living by himself, so he moved back to Granny Harriet’s house, where he wandered through the rooms, broken binoculars around his neck, mumbling to himself.

So spring passed. We planted seeds and prayed for a better crop next year. The oldest children started new apprenticeships, new jobs. Nicole was caught with Tommy Jenkins in the Jenkins’ barn on a Sunday afternoon. And except for Grannie Harriet, no one ever saw crazy Old Stevie. We relished in the normalcy of it all.

If we missed the thrushes singing, well. The crops had to be planted, the shirts had to be sewn, the children had to be taught. We turned back to our tasks and ignored it.

The Mayor was holding the first town hall of June when Granny Harriet stumbled in, hair springing out of her bun.

“Stevie’s gone,” she told us. “Stevie’s missing.”

We had never thought of locking him in. He didn’t like going outside anymore, would cower on the ground, hands over his head. But Granny Harriet didn’t lie, so we trooped out of the meeting to her house. The door was open, the house and everything, even Stevie’s shoes, untouched. But the binoculars were gone, and Stevie with them.

No one knows what happened to Old Stevie Wasserman after that. We searched, but never found any trace of him. Some say he must have drowned himself in the rain-swollen river. Others say, no, though he might have fallen in by accident. But Tommy Jenkins swears he saw a stooped figure walking away from the village that day. A pair of broken binoculars hung around his neck, his eyes cast down so that he might not see the empty sky.

There is a crustacean crumbling in her hands. In the dark, it is a dull white, the color of a pomegranate seed, in the place where it presses closest to the red skin. It is dignified for something that is dead. Its little legs lie limp like strings but it shimmers in the stars’ light, perfectly clean. The lake cleaned it and when I touch it the gritty water sticks to my fingers. It sits in two halves, nestled together to imitate a whole. I wonder why its body is cut clean in two.

Francis, she names him. I tell her that it’s a good name for a crustacean. He has come to life. (This is not true. He’s dead.)

Francis has that unconventional crustaceous charm of the deceased. (You know the one.)

In the night next to him, the sky and sea are perfect twins and the world feels infinite in their imitation of each other. Then the waves catch the night’s faint light and the image violently flips and everything is suddenly small, so small that I cannot tell the difference among us, and I look to Francis and I feel as if we are friends. The three of us have been friends for years, our entire lives, and we stand on the shore laughing about old jokes and silly children

and whatever else old people (and old crustaceans) laugh about.

We dress him up. We make Francis a crown of grass, place him in a boat of leaves. He is a Viking king in a regal carriage, headed for the land of the dead.

A leg breaks from his body, and I hurry to put it back into place. I am careless, and another leg breaks, leaving lines of jagged legs like an old and broken comb. We leave him in an expensive boat by the pier, so that someone else can find him in this state of derision or dignity.

I read a Pablo Neruda poem recently.What inspired that reading I don’t recall; I was perhaps forlorn and maybe sentimental and very likely needed to just go outside. I do things like that sometimes, when something bothers me and I don’t know why, or when I feel lost. In effect, it’s a meditative practice—not the poetry, but the search for something prescriptive. The poetry is pure circumstance.

I think I remember it more clearly now: it was one of those quotes you see quickly in passing, maybe on the wall, framed in a neat wooden frame, on sale at TJ Maxx or a Kohls—no, not a Kohls.

At a TJMaxx then, displayed on a wall was a quote from a Pablo Neruda poem. I don’t remember the exact lines or words, but it was the vulnerability that caught my attention. I looked it up later and read it in full.

Tonight I can write the saddest lines. Write, for example, ‘the night is starry and the stars are blue and shiver in the distance.’

The night revolves in the sky and sings.

Tonight I can write the saddest lines. I loved her, and sometimes she loved me too.

I sent it to a friend, I knew he would be interested in it. A

few days later, between the cracks in my iPhone screen, I received a thumbs up notification accompanied with simple text: “This is beautiful” Indeed, the brevity of his statement underscores the poetic beauty of Neruda’s writing. It is beautiful in its simplicity and its seemingly effortless delivery: Sad and probably alone, he writes about his failed romance on a single brisk, blue, starry night and delivers something remarkable. When I read this poem, I find something especially impressive in the candidness of his words—something that feels real and unfabricated and intimately personal and that doesn’t exactly fit the typical narrative of unrequited love.

She loved me, and sometimes I loved her too. How could one not have loved her great still eyes.

Tonight I can write the saddest lines. To think that I do not have her. To feel that I have lost her.

To hear the immense night, still more immense without her. And the verse falls to the soul like dew to the pasture.

He was no victim of just unreciprocated love, but of a noxious relationship. A malign recurrent theme characterizes some of these lines—some horrible cyclic motion that characterizes Neruda’s relationship. You can see it in the repetition of its titular phrase throughout the poem; you can see it in the witty reflective nature of the phases: “I loved her, and sometimes she loved me too,” followed by “she loved me, and sometimes I loved her too.” He seems to present us a flashpoint without artifice, a moment stripped of inhibition, hesitancy, or pretenses regarding the nature of his romance.

What does it matter that my love could not keep her.

The night is starry and she is not with me

Like adolescents avoiding a hard conversation, we sit at dinner and labor over reasons to avoid talking about love, pushing our asparagus onto the floor to amuse ourselves with the dog instead. When we are inevitably confronted with the subject; we talk about love like we talk about politics: parlor conversation less concerned with content than with rules through which we deliver it—absent of stakes and inherently vapid. Neruda talked about love like only a poet could: bringing it up high and in the spotlight and splattering it across the page—ruthlessly authentic and maybe a little too sentimental, but at least in earnest, truthful.

***

We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

Joan Didion wrote those words, which are the first lines to her famous essay collection, The White Album. Her words were meant to warn us from falling into the peculiar fallacies of sentimentalism and wishful thinking that essentially constitute a slippery slope into a certain distasteful thought-pattern. Over the years, people have taken these words and twisted their original purpose—which was an indictment of the over-sentimentality of American culture—to contradict her meaning.

I recently talked with a friend of mine about love. He was lamenting about his current involvement, which is what I’d imagine most would characterize as a failing, somewhat poisonous relationship. It was the same story I have heard for a couple years now: a difficult long-distance situation that had started sweet in university, then extended through the pandemic lockdowns, an online graduation, and now sat in waters stagnated by 5,000 miles and a five-hour time difference. Yet, through the years of unwarranted accusations, toxic phone calls, and cautious advice from friends, they stay together—perpetually locked into an arrangement neither of them want much of. Whenever this issue came up,

sometimes over coffee but usually between a bottle of Jameson blackbarrel whiskey, I would jockey my friend about his irresponsible behavior, push him to be rational, and interrogate him for reasons to perpetuate what I saw to be a disaffected romance. Why allow each other to sit entangled and unhappy and waiting for catastrophe to precipitate, especially when it could very well end with a phone call? In turn, he’d spend the night convincing me that the two of them were remarkably gifted at settling disputes together. Once, in a small surfing cove up the coast, the two of us sat under a bright moon. We both enjoyed the pleasure of a cool, clear summer night, and so we had built a small campfire near the front of the beach where we watched the waves crash against the sand and the faint, impassive stars glitter through washed-out moonlight. These fires have the quality of always coming at the right time—it was just us, sitting a little ways from each other and the heat, sharing a bottle of Bulleit rye. After an hour or so, we had fallen onto the topic of his romance. I inquired—one more time—about his intentions, and received the same story. But between the fire, the whiskey, and good company there was a tense understanding of something undeniable. A lull in the conversation took hold, and we sat mesmerized by the flames. I thought about his situation, turned it over in my head a few times and tried to understand his point of view.

The water was lit by the half-to-full moon overhead, speckling the reefbreak with a somber twilight sparkle. The waves looked larger than normal, as they always do on moonlit nights. They looked dangerous and menacing as they crashed against themselves just offshore so that their white-water surged towards us and sloshed a ways up the shoreline. Some would assume danger but I recognized the familiarity of the mirage—I’d seen it since the first time when we, my buddy and I, went surfing at night on that same beach. Our backs to the shore and thigh-deep in the water, we pushed out and onto our boards towards the nightshaded waves—both nervous and looking ahead, hoping for the best. After that first push, and through the break, we would sit on our boards and look around and realize that these were the same waves, cresting and breaking in the same fashion

during the day. He smiled at me—I remember he smiled a lot back then—and it was bright enough to see each other’s faces. And in that moment with the seascape and the moon surrounding us I wondered why we had been afraid. I brought that point up to him back on shore and he said he didn’t know either, so we had a good laugh and called it a night.

So, I have recognized that tricksy mirage since, and I looked out onto the crash and tumble of the moonlit water and reckoned that there was nothing out there except the same foam-crested waves I’d known since childhood, shaded sinister by an expert illusion. I sipped my whiskey and poked at a log in the fire, turning it so that the flames could reach fresh wood—I felt their heat on my chest as they spread quickly across the bark of the driftwood we had collected for fuel. That, coupled with the whiskey, had me feeling quite warm.

I watched the moon closely now, it was low in the sky now and darting quickly towards the horizon. I looked at him through squinted eyes, and I asked him if he thought all that trouble was worth it. He told me “the pain has to mean something, doesn’t it?” There’s no easy way to respond to that statement, so I just settled for a nod and shrugged in acknowledgement and left it there. Grief may be the price paid for love.

During a long conversation spent half-submerged in the waters of a fairly popular stretch of shoreline in Keaukaha, another friend of mine spent the better part of a lazy afternoon explaining a particular situation. He and I have done this for years—since we could drive ourselves to the beach and lounge together in the heavy tropical afternoon sun.

He was lamenting that he had spent most of this past year— and the year before that—feeling deeply unsatisfied and unsteady, concerned about the prospect of never properly letting go of the closeness and rustic inertia of Hilo—our small hometown neatly situated on the edge of a large bay on the Big Island of Hawai’i. He

wanted to jetset to the mainland to explore the United States and see exotic places, experience a different life, and discover some essential truth about himself along the way. As bulbous clouds overtook the sun, we moved out of the chilly water and onto our beach towels. I picked at some chords on my Lanikai tenor, and he articulated his plight in further detail onto the beach.

He was waiting for something: that singular instance of electrification in which readiness was upon him and he was no longer restrained by—as he described it—his childish impulses to make his move. “It’s about finding the right moment… it’s all about the right moment,” he said at one point. He would punctuate his silences by throwing ripped pieces of grass into the small tidepool next to us. In the meantime, he would be working a holdover job, a remarkably well-intentioned, albeit labor-intensive, gig with an environmental restoration group on the island. It was hard labor, and the pay was terrible, but at least, he insisted, it was “a meditative experience.” He liked his job in other ways too, and he had met a certain someone special who worked with him clearing out restoration sites. They were set for a hiking date in search of an especially exclusive waterfall some ways up the coast the following week.

“There’ll be no tourists, so it will be quiet for us,” he exclaimed proudly, and I nodded in understanding and strummed a tense E7 chord on the Lanikai. Our patch of grass, which was surrounded by the rocky shoreline, was empty except for a youngerlooking couple and their dog, who momentarily came to examine us and sniff at the lychee peels we had piled during our conversation. We sat in silence for a while and I thought about all that he had told me, and I wondered out loud if he had ever read On the Road, which he hadn’t. I thought to myself that he should read the book, but I suppose it’s foolish to expect things like that, so I suggested he watch the movie instead. In any case, the chill got to us both and the evening was nearly upon us, so we headed to a bar featuring an EDM set for its weekly showcase and didn’t speak much of his ordeal again. However, that whole interaction hasn’t left my mind since:

something about the situation was off-kilter—the water lapping at our waists, the ponderings on place and meaning, even the dog and my ukulele. The image in my mind has some reverberatory quality to it—something keenly harmonic—and now I realize that I had been there before in that exact space. We’d had the same conversation the year before, and the year before that, and nothing had much changed since the last time we spoke and stood, half-submerged and chilly, talking about life and love while I strummed bluesy arpeggios on my ukulele. I wondered then if he had read On the Road too, and he hadn’t—but today, thinking about that whole scene strikes a cold and shivery chord throughout my entire body. Today, I think back to my other friend, and I remember he once told me he didn’t see a future for him and his girlfriend—I remember that statement as almost an aside, something of a slip of tongue. I was quick to probe what he meant, and he confessed he was waiting to break up— maybe after Christmas or New Year’s, or after she came to visit—but either way now, as he put it, wasn’t the “right moment.” Today, Joan Didion has died, and now I can’t help but wonder if all the decisive right moments have died with her too, leaving us alone with those meandering stories we tell ourselves.

***

I read a Pablo Neruda poem recently, and now I think I remembered what inspired that reading, but that point doesn’t matter as much as what the reading inspired in me. Maybe it’s something about the poem’s subject, something about the beautiful vernacular of rotten love that piqued my interest:

I no longer love her, that’s certain, but how I loved her. My voice tried to find the wind to touch her hearing.

Another’s. She will be another’s. As she was before my kisses. Her voice, her bright body. Her infinite eyes.

I no longer love her, that’s certain, but maybe I love her. Love is so short, forgetting is so long.

Because through nights like this one I held her in my arms my soul is not satisfied that it has lost her.

It’s because I know these words that I can pull out some of my own writing and recognize the same somber adjectives and achy voice and restless tone and realize that I have been in that sad, twisted moment too. I have been in that seat, sad and alone, twisted inside and running through the same circles in my head. I have sat on a shoreline, late in the afternoon, painfully discontent and dispirited. I’ve sat on a beach harboring misaligned values and a sore heart— wishfully believing in the ghosts of a dead romance. I’ve even told myself that the pain is worth it in the end and earnestly believed it. And, it seems, so did Pablo Neruda. However, I am not Pablo Neruda and I missed something crucial that he didn’t. So did both of my friends, who, to some extent, may both still be waiting for the right moment. So did everyone else who grew up believing in certain things that we shouldn’t have. Maybe, getting over the artifice is something you need to do first-hand, but I have my doubts about that sentiment. Pablo Neruda, to his credit, wasn’t afraid to let the world know—he wasn’t afraid to sit and shiver, feeling dim and blue, and etch his last lines into permanence for the rest of us:

Though this be the last pain that she makes me suffer and these the last verses that I write for her.

Neruda knew something about the right moment. In his poem he may have been speaking about love, but his message cannot be taken for something so insular and narrow. In a way, all this talk of love was really a conduit for better understanding the essence of the right moment. He knew something about the choices that confront us and the fantasies we choose to let ourselves believe, and

he decided—then and there, pen to paper—to take a stance, choose a path, and get on with it; anything else more, I believe, would have been wasted words.

“Tonight I Can Write the Saddest Lines” – Pablo Neruda. Translated by W S Merwin and A.N.Other.

For our last meal, I took you to the Creamery off Ramona. We ate on the patio. It was empty, but us. We could have watched the cars at the intersection. Two separate drivers played music so loud. Or the group of kids we probably knew walking from the stadium. We could have talked. But we just feasted. Caribbean French toast. Banana chunks in the syrup pool. Egg fried on top like candy. Smoked salmon. Chorizo sausage mixed in hash browns, doused in Tabasco. We woke up so late, that last day. Lazily, like there was no red-eye home or “intrinsic differences” between us. And when we walked around the square after, we could have stopped looking at our shoes. We could have sat on that bench by the duck pond and let our mouths go over glass reflection. We could have looked up, even.

We could have seen the sun sliding away between that church steeple and the museum on the corner. But instead, when my gaze lifted, it wasn’t to talk. I just stared into your eyes and felt it.

my bedroom door shuts and i’m at it again. tearing off frayed ropes of skin, mouth tasting of salt and metal. then i yank my fingers from my teeth and set them on the table. my hand is fissured: barren earth. skin flaking like a thin layer of permafrost. lava oozes out from blackened flaps of volcanic flesh. i stare at the raw cuticles, nails bitten to stubby ridges, fingertips picked at and eroded to white calluses. then i stuff hands back into pockets. dormant until the next eruption.

bump off a knife in the back of the record shop stop to smoke by the side of the pier poke fun at the sign that says no smoking no alcohol get a beer lie in the grass open your eyes too wide wonder if you hallucinate that squid in the sky no it’s a kite close your eyes tight breathe through the bad trip go for a dip off the end of the pier get another beer beer blow some guy on blow at the end of the pier in the bathroom come down get found in bed with someone you don’t know don’t stay sober long enough to care you don’t dare ask his name do the same same same then leave town never see him or his name around along every rail tie between here and there get gone get gone gone gone on the train say casey jones was the one to blame then stare out the window pane and watch your fears click against piano tile ties watch someone jump out and die cry on the phone cuz your people don’t want you to come home and then write this poem.

serrated fingers drag along the murky waters that lie in the canals of your skin you are shriveled like a raisin only meant to eaten by the man who is blind to the wisdom that lives within and deaf to the soft notes of the hesitation that is often left unheard he sinks his teeth into the nape of your neck his eyes feel unwelcome as they browse your body like a magazine you are merely a product to be consumed, and fault is easier to digest when it’s on you so you don’t say no you can’t say no

we are driving back from a hike the one where it was hot and that’s to be expected in the apparent midwest in july of 2021 and with eight bodies raised in fog and a distaste for anything above 70 but then it was miles of dust flying up around us and the balmy sort of sun block sheen that makes your hands avoid themselves and one of the siblings had caved then lifting a dim weather app to say 104 which was validating at the time but also miserable and i was playing games in my head at the wheel with whether or not to keep the ac going while the windows were still down and at what angle might both be optimized to survive triple digits in a stuffed car. but we are driving. and on the way we pass an olive garden and i give a heat delusioned fantasy of the baby sister fisting those bastardized breadsticks all small hands and new proportions and someone in the back reminds me that i don’t like pasta but with the sort of voice that is also somewhat amused by breadsticks and the baby and later that night it is us at a round table anyway and there are breadsticks mixing with the oil and sunblock on our fingers and we are laughing about free refills and how dad pronounces gnocchi to crystal with the cheese grater but underneath that is the awe of the sun still in our eyes is the fear when dad jumped into the lake is the bewilderment of those thickened seconds of who would jump first to follow him across is the anxiety from how the water smelled is the green brown algae blooming murky between our toes is the memory of my brother coughing water because he hadn’t swum since he was a toddler is the silence of the six of us following each other across and the willingness to play the part a while is the fact that kevin is no longer a toddler. my brother puts his head in his

hands funny when crystal with the cheese grater charges us for a second lemonade, and at the end and after it all my dad takes a picture of us, eight people steamy and beaming and slightly sunburnt underneath the ten pm olive garden sign. in the photo i am smiling but holding my breath and also a bit sad, that we left without saying goodbye, that joy was just the moments where i should have.

On the sand a Catholic priest shed his cassock and collar and kissed me many times, gently. We picked reeds out with our thumbs and in the bonfire we watched them burn out like bouquets of sparklers. The wind traced its nails across our backs. We shivered, then held each other closer, panting. I dug my hand into the earth and lifted a mound of wet sand crabs, crawling over each other to bury themselves again. He laughed and picked one up, then threw it into the ocean. It soared but made no sound as it splashed in the water. I studied at the altar of him but never learned.

Gila Wilderness. Western New Mexico. 1847.

Dwarfed by the immensity of the landscape, the wanderer leads his mule across the unforgiving terrain. His steps are labored and halting. His beard is haggard and unkempt. When he scratches, flakes of dry skin fall to the rocky ground. He is not old. But not young either. Blankets, canteens, a rifle and a lute-shaped guitar clang against the mule’s body, marking the rhythm of its stride. Its ears twitch, pestered by flies. Its hooves leave tracks in the red, cactus-speckled clay. It knows nothing of what he has left behind. Or where they are headed. It simply marches forward, fearing the whip…

Dusk — The wanderer leans back against a lone ponderosa pine, reading an old Blood and Thunder novel with a caricature of Kit Carson killing legions of savage Indians on its cover. The mule grazes nearby.

Night — The wanderer sits in front of a campfire playing the old guitar. Singing the blues. Sparks from the fire spiral upward into the darkness.

A sickly old vagabond stumbles into the firelight. The wanderer leaps to his feet, slicing open his left palm on a rock on the way

up. He yelps. The vagabond stares at the wound.

Apologies. Had no mind to startle ye.

The wanderer’s eyes go wide. He recognizes the old vagabond from the cover of his book.

You’re... Kit Carson.

The wanderer offers the vagabond his clean hand.

Name’s Oskar.

The old man just stares at the blood streaming from Oskar’s palm. Oskar follows his gaze.

Hm.

Oskar digs in the saddlebags for a kerchief and wraps it tightly around his bloody hand to stanch the wound.

C’n I offer ye sumthin’ t’eat?

Carson shakes his head, his eyes never leave the bloody palm. Oskar pulls some dried meat and stale bread out of the saddlebag.

You ever seen one a’ these?

Carson shakes his head.

They calls it a gee-tar. Picked it up off a merchant out Texas way. Reckon t’ennertain them troops at Fort Marcy with it.

Oskar grips the neck of the guitar with his bloody hand and

plucks a few chords, fighting through the discomfort to entertain his hero. Carson watches blood saturate the kerchief.

What’s it like...? Spyin’ yerself on the cover o’ all them books?

Carson picks up the book, examines it and scowls. Don’t pay ‘em no nevermind. Ain’t one true word in ever’ five. He tosses the book aside. You done had yerself an adventure or two, though, ain’tcha?

Waiting for an answer, Oskar picks up the book and tucks it away. Carson deliberates.

I seen a thing or three.

I been wantin’ to have me some adventures like yers fer long as I c’n remember. It’s on account o’ you I’m even out here to start with.

He waits for something from Carson but nothing comes. Sure you won’t take some o’ this meat? It ain’t no trouble. I’ll get by. Oskar packs the food away.

I always imagined myself on one o’ them covers. Fightin’ Injuns, havin’ adventures. But that’s hubris, I s’pose. Ain’t Christian. I’ll show ya somethin’.

Carson leaps across the fire like a rabid dog. He grabs Oskar’s hand and sucks the blood from his palm. The two men fall back on the hard ground. Oskar struggles. The old tracker is strong. Impossibly strong. Desperate now, Oskar reaches for a rock. He pounds it into Carson’s temple. Oskar is blinded by spurts of blood from Carson’s face. It flows into Oskar’s eyes and mouth. Oskar struggles loose, wipes his eyes and scrambles to his feet, spitting out Carson’s blood in watery red globules like embers from the fire. He unsheathes the rifle and points it at the old tracker.

Don’t make me. I don’t want no part a killin’ a legend.

Carson’s gaze is black ice piercing through the firelight straight to Oskar’s core. The old man spits. He wipes his mouth with his sleeve. Carson slinks off into the darkness.

Morning — Oskar sleeps in a ball on the frigid earth, arms wrapped around the rifle. He blinks. The sunlight plunges into his ocular nerve, a hot knife slicing brain. His head throbs. He wipes his face. Oskar examines his hand. It is already scabbed over and scar tissue is forming.

A woman, young in age but not experience, looks up from her book. Standing in front of her is a half-Hispanic girl in a yellow

dress. The woman tucks tendrils from her blonde mane behind her ears. The little girl is shy. The woman smiles. They share a silent moment.

Hi. Hi.

My name’s Allie, what’s yours?

Scarlet.

Nice to meet you, Scarlet.

Scarlet looks back over her shoulder at a wiry caucasian man with a mustache, wearing black leather gloves on a hot day. The man waves. Allie asks:

Who’s that?

That’s my daddy. Okay. Bye. Bye.

Allie watches Scarlet walk back to the man with black gloves. She checks the time on her cellphone. Sighs. Dials a number. Waits. No answer. Voicemail. A deep, gravely voice growls into the phone.

You’ve reached Randal, but this ain’t me...

A matte black 1950 Mercury sedan refurbished down to the whitewall tires and leather interior pulls up to a fleabag motel, the “El Rey Inn.” Allie scrambles out of the backseat and pulls her

luggage after her.

Thanks, Clarence. De nada.

The wiry man with black gloves speaks Spanish as if it’s an extension of English. It’s unsettling. That someone can speak it so well, so coldly.

Bye Scarlet. Bye. We’ll see you around, guapa.

The musty air inside the motel is cigarettes and stale sweat. An obese clerk watches TV behind a pane of bulletproof glass. Allie stands at the desk.

Hello? M’alp you?

The clerk doesn’t bother to look up as he speaks. I’m looking for someone. Room 217.

You’re looking for Randal. I’m his daughter.

The clerk snorts. Looks her over. Slowly gathers himself and stands.

I’ll take you up.

The clerk lumbers up the stairs. At the top he turns and watches Allie struggle up with her bags. He leads her down the hall and pounds on the door to room 217.

Randal! RANDAL?!?! He’s basically deaf. Never answers.

The clerk pulls out a key ring and opens the door.

The curtains are drawn, the room shrouded in darkness save a pale glow from the blaring TV. Light from the hallway illuminates the cans of Pabst Blue Ribbon that litter the floor. There is no furniture.

Randal? Someone here ta see ya.

No answer. The clerk shrugs and lumbers off down the hall.

Hello? Randal…?

Allie cuts a path through the beer cans to the TV. She turns it off. Opens the curtains. A burly middle-aged man leaps up from a cot in the corner. Allie stumbles backward and screams. He is shirtless and barefoot. His tattered jeans are unzipped and his breath wreaks of booze. He sizes Allie up.

Keep ‘em shut, hear me? Light hurts ma eyes.

Randal pulls the curtains shut.

Yer momma sent ya.

Yeah.

Huh? Come on, speak up girl! Yer speaking in tones too low for the human ear.

He fiddles with his hearing aid. Yeah! She kicked me out!

She still a whore?

Randal switches the TV back on. He walks back to the corner and collapses onto his cot where he lays propped on an elbow, sipping beer from a tallboy. Allie just stands. Randal tosses her a pillow and a sweat-stained sheet.

You can sleep on the floor. Ain’t nowhere’s else.

Allie turns over onto her back and stares at the ceiling. Somewhere in the motel, someone has violent sex with a prostitute. Somewhere else, tenants throw things at each other and scream. The TV blares. Randal snores. Allie gets up.

She opens the refrigerator. Inside are three tallboys of Pabst, a few ketchup and mustard packages, an ancient box of baking soda. Allie takes a can of Pabst. Holds the cool metal to her forehead. Slumps to the floor. Back to the wall. Tears roll down her cheeks. She closes her eyes…

Allie feels Randal on top of her, struggling with his pants.

Be a good girl and show daddy what yer mama taught ya.

Allie tries to roll over and shove him off. He’s too heavy. They

struggle. He leans in close, trying to wriggle her pants off. She screams into his ear. He slaps her and sticks his hand over her face. Tries to muzzle her. She near bites his thumb clean off. He punches her in the stomach. She finally releases his thumb and he roars in pain. Stumbles backwards. He snarls. She grabs the full can of Pabst. Hurls it. He turns away. It strikes him in the temple. He staggers toward her. Dazed. Likely concussed. She sprints out the door.

Allie walks down Central. Crying. The streets are empty aside from a drunk, homeless junky who calls to her. Allie turns a corner. The junky follows. Fear, desperation and anger collide. Allie spins and screams at him.

What?!?!

The junky stops cold. He fidgets and sways and slinks away. Allie exhales. Clarence’s black Mercury sedan pulls up.

Yo! Allie! Wassup girl?

Allie and Clarence sit on a plush leather couch in front of a massive TV watching Jerry Springer re-runs.

So, who do you know in LA?

No one. I just gotta get outta here.

Clarence’s apartment is white and bare. The under-furnished lair of a bachelor with money but no mind for decoration. The carpet is stained with cigarettes, weed, beer and other things. A Greyhound Bus ticket lays on the coffee-table.

Sí, pero… You’re moving there with no diñero? Nada?

Don’t have much choice.

You could stay, que no? At least until you make a little cash. How?

I can think of a few things. Pretty girl like you? Sin problema. I just want to get the fuck out of here.

Allie wakes up on the couch. Fully clothed and drooling. A blanket draped over her. She wipes her mouth slowly, finding her bearings. She leaps up. Searches desperately for a clock. The timer on the microwave blinks zeroes. She sprints down the hall and throws open Clarence’s bedroom door.

Clarence sits up. He rubs his eyes.

Is it...?

He rolls over and checks his phone. Seven-thirty. Puta madre. What time is your bus?

An hour ago. Fuck. I can’t believe I fell asleep. I can’t fucking believe I fell asleep…

Pinche pendejo de la puta madre. I’m so sorry Allie.

It’s a non-refundable ticket. I’m out of money. No te preoccupes, Allie. I’ll get you another ticket, I promise. I’m taking Scarlet to the County Fair today, quieres ir?

The fair is shiny and bright, and busy. Young couples ride the ferris wheel. Children squeal and run from tent to tent. Old folks munch on candy corn. Scarlet drags Allie up and down rows of parlor games. Eyes vacant, Allie allows herself to be led.

At Scarlet’s urging Clarence hands Allie a handful of darts. Allie’s expression subtly shifts as she throws darts at balloons pinned to cork boards. Darts become basketballs, basketballs softballs, and softballs BB guns. Soon, Allie and Clarence coach Scarlet through a ‘Whack-A-Mole’ game.

The three pile into an instant photo booth. Scarlet wraps a feather boa around Allie’s neck and plunks a cowboy hat on Clarence. For herself she selects a toy pistol and bandit’s mask. She playfully points the pistol at Allie. Scarlet’s enthusiasm is infectious. They pose like outlaws, making mean, threatening faces while the camera snaps away. They laugh at the pics, Clarence hands them to Allie.

Here. Something to remember us by. Allie and Scarlet share a bumper car. Allie presses the pedals as Scarlet steers frantically with Clarence in hot pursuit. They buy cotton candy and ride the mini roller coaster and ‘Tilt-aWhirl.’ They have dinner at the food fair as the sun sets and the lights come on. Then they ride the giant swing. And ferris wheel. Peering down on a rodeo, in full swing. Scarlet falls asleep on Allie’s lap. Clarence covers her with his jacket and snuggles up close to Allie.

Back at the house Clarence tucks Scarlet in. Scarlet reaches for Allie. Allie gives her a hug and kiss.

Allie and Clarence sit on the couch drinking beer.

Good day. Scarlet really digs you, I notice.

Her face don’t lie. On the bumper cars? Orale! Fuckin’ priceless.

She’s a riot.

Clarence slides closer to her. He puts down his beer. He leans over. He kisses her on the mouth. Allie is tentative. Lost in thought. Frozen. She doesn’t respond. But she doesn’t resist either. Clarence takes the beer from her hand and puts it on the coffee table. He takes her hand in his. He stands up and leads her down the hallway. Allie allows herself to be led.

Clarence kisses Allie once more. He continues kissing her and slowly removes her clothes. Then he lays her on the bed. He stares at her as he removes his clothing. It’s business-like, not sensual. Clarence is in complete control. He straddles her.

Digame algo. Tell me a story, baby.

I like hearing about my girls with other men. It turns me on.

***

Ronnie’s Roadhouse. A small saloon on the outskirts of Albuquerque packed with old drunks, truckers and young hipsters discovering its dive bar charm. The steady finger-picking of Oskar’s cover of Townes Van Zandt’s ‘Waiting Around to Die’ fills the room. Though his clothes are different, Oskar looks the same as he did 170 years ago. While he plays he watches Allie dance with a drunk trucker. Her expression miles away. Oskar finishes the song. The trucker leads Allie upstairs.

Oskar talks to the bartender. At the far end of the bar, Allie sits. Quiet. Staring, listless, at the photo strip of Clarence, Scarlet and her from the fair. She takes the pointed corner of the strip and presses it into the pad of her index finger. Hard. She grimaces in pain, but keeps pressing. Oskar sidles over.

Who’s that?

Allie shoves the strip into her purse.

Just some friends. Buy you a drink?

I’m off the clock.

So am I. My boyfriend’s on his way.

You mean, your pimp?

You’re blunt. Do you like your job?

Allie stands up and gathers her things.

I’m sorry. Really. I didn’t mean to offend you. Let me make it up to you.

Oskar waves the bartender over.

What’re you drinking?

Oskar and the bartender wait for her response. Allie scrutinizes Oskar’s disheveled appearance. Oskar tries again.

It’s my birthday. Please. I don’t want to drink alone. Will you join me?

How old are you? 170. Allie snorts. Oskar smiles.

Oh yeah? You don’t look a day over 169. She turns to the bartender. G&T, Sam.

Oskar helps her back onto her chair and sits. Allie steals his question.

Do you like your job? No.

No? Does that surprise you?

It does. I thought all musicians loved what they do. I’m not a musician. No? So what are you?

Just a wanderer, I suppose. Why music then? There are lots of ‘just jobs.’

It’s just what I do.

A purpose.

I don’t know about that…

They sit in an awkward, pensive silence for a long moment. Allie absently sticks her hand in her purse, fiddles with the picture, regretting her decision to stay.

I apologize, if I seemed crass earlier. I don’t play well with others. But I really am curious about your thoughts on your profession…?

He waits for an answer. None comes. He keeps going.

It is the oldest profession, perhaps even a noble one, some might say, from a certain perspective… I can fully appreciate how one might… Are you going to let me keep rambling…?

I was kind of enjoying it. The bartender hands Allie her drink. Thanks. Cheers. Allie takes a sip. Then: Let’s just say, it’s not exactly what I imagined I’d be doing with my life.

You thought maybe you’d be doing something with more... Purpose?

Yeah. I guess. Yeah.

You know, the Chinese, they’ve got this idea — You been to China? Yeah. Allie is impressed. Oskar continues his story. Purposelessness. Here, we say something’s purposeless, it’s an insult. It’s worthless. But the Chinese, they hear it and think: ‘that’s just great.’ It’s a compliment. It’s like laying in a field and looking up at the stars. Or going for a long walk, not caring where you end up. Music is purposeless.

He looks at Allie.

And dancing. When you dance do you aim to end up at a certain spot on the floor? Is that the point of dancing?

No.

It’s the same with life. We think life has a purpose. No. It’s the waves lapping against the shore, again and again, endlessly…

Oskar sips his drink, letting his words linger. Allie pulls the photo strip out of her purse and scrutinizes it once more.

The sound of a break — colorful spheres of resin and plastic smashing together and firing off in all directions — from the pool table on the other side of the room fills the silence. A couple argues at a table in the corner. An old drunk snores, hunched over his beer. Finally, Allie speaks.

It’s true. The point of dancing isn’t to get somewhere. Or do anything, really. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t have a purpose, though. Sometimes, every once in awhile, when I’m dancing I forget where I am.

She stares blankly at the photo as she talks, pressing her index finger into its sharp corner once more.

I kinda get lost in the movement, you know…? Sometimes, I even forget who I am. For a moment. That’s nice. I like that.

Oskar scratches his beard, tugging on a few lengthy whiskers.

Here’s to forgetting to remember. Here’s to remembering to forget…

Allie presses her finger into the photo even harder now. Tears welling in her eyes. The bartender ambles over.

Startled, Allie stumbles forward, her finger slips on the edge of the photo. Oskar grabs her wrist to steady her. A crimson droplet balloons from her finger pad, Oskar stares at it for a frozen moment. Then he grabs a cocktail napkin and presses it to the wound. She pulls her hand away. He gently lets go.

Alpine Time Nur Shelton

I want to know my grandmother, so I take everything she has given me and lay them out one by one on the kitchen table. It is a bizarre menagerie of antiquated things: white bobby socks cut with lace, a Lions International travel clock, a selection of sleek 45s, a tan blazer embroidered with the memory of a nonAnglicized name. I pause to admire each item as I remove it from its plastic wrapping and stop when I come to a particular record. A 45 marked with a memorable orange-yellow gloss swirl, it is Kyu Sakamoto’s hit 1961 single, Sukiyaki. Like my grandmother’s name, Sukiyaki was not the original title. To the Japanese it was known as Ue wo Muite Arukou, or I Look Up as I Walk, but following the song’s massive commercial success in the United States, Americans took it upon themselves to christen it with the only proximal Japanese term they could conjure up: the name of a traditional dish of slow-cooked, thinly-sliced beef. Reclaiming is a difficult process. It is even more difficult when you take into account its ugliness alongside its valor, that when you pull pain at the root, you are also pulling up the roses that bloomed from it. I search the kitchen for the knife block and take the knife with the largest blade. I set my grandmother’s record on the cutting board and bend my elbow for leverage, the tip of the knife sliding over black vinyl and striated song. What do we gain when we remake the things that hurt us? What purpose is there in healing if we willingly reopen the wound? It takes a long time for food to settle in one’s stomach, to digest and absorb the nutrients and expel the toxic waste. But for now there is still time for the thinly-sliced shards to make their way down the esophagus, for the sharpened bits to skin and scar the organ tissue, for the blood to well up in the throat and coat the tongue.

In Hemingway’s six word story everyone sees the dead child.

Stillborn. Unworn shoes and a threadbare future. But nobody ever talks about the ones who come after the dead.

How can you compare to a corpse? Years before me, an expectant mother, belly swelling like a sarcophagus. A perfect baby— brown with black curls, her life twisted into the cord around her neck.

It is clear I was contingent on the monstrous shadow of a ghost.

My life is a chalk outline. My parents scatter ashes across the Pacific and I get good at not asking questions.

Hannah Cha (visual art) is an artist and humanitarian, dedicated to innovating with her creativity. Being a freshman new to Stanford, she explores the overlap between social justice and art through stickers, art prints, and paintings. Matcha latte in hand, she hopes to make a positive, social impact in the world.

Leah Arima Chase (poetry, visual art) is a junior majoring in English. Their work attempts to uncover the historical processes of race and gender through visual and textual mediums. Their poetry also features a focus on the body as a site of violence, trauma, and healing. In their spare time, they like to hike, read children’s fiction, and tend to their plants.

Adam Chin (Prose) was born in Toronto and grew up in Vancouver, BC with his Chinese-Jamaican single mother with visits to his hippy father in Santa Fe, New Mexico. After dropping out of a professional acting program to travel the world making films, he now finds himself studying screenwriting at Stanford.

Jennifer Co (she/her) (poetry) is a Chinese Filipina writer and sensitive eldest daughter from Brisbane, California. She recently graduated from UC Berkeley’s Chemistry and Creative Writing departments, where she was literary editor for {m}aganda magazine for two years. She is currently pursuing a PhD in Chemical Biology, and is continuing to try to find the words.

Cole Dill-De Sa (prose) is from Hawai’i.

Isabelle Edgar (poetry) is a sophomore who calls Woods Hole and many people home.

Alice Fang (visual art) is obsessed with stories. She reads, doodles, stares at moving pictures, and writes frantically with her mental typewriter on a daily basis. She enjoys good food, dog-watching, and amusement parks. Her short-term goal is to start a comic strip.

Caroline Gao (visual art) earned her symbolic systems bachelor’s degree June 2020 and is now finishing up her master’s in computer science. Though her degrees show otherwise, Caroline loves the arts – writing, drawing, painting – anything creative, really. Outside of academics and art, Caroline enjoys cycling, Chipotle, and a good prank / pun (which to her, is also considered an art).

Elizabeth Grant (poetry) is a senior at Stanford, where she studies English and the Creative Writing Poetry. She is from Southern California, and loves caring for her many plants.

Surya Hendry (poetry) is a junior studying Political Science. She is from Seattle. She writes, occasionally.

Anna Kiesewetter (poetry) is a freshman at Stanford University from Issaquah, Washington. Her writing has been recognized by the Scholastic Writing Awards and Skipping Stones, and can be found in Polyphony Lit, Blue Marble Review, Prometheus Dreaming, and Rising Phoenix Review. A firm believer in the psychological nature of literature, she writes to explore the complexities of human experience, identity, and perception.

Yasi Khan (poetry) is a senior majoring in Symbolic Systems and minoring in Creative Writing (Poetry). She is from San Francisco.

Connor Lane (poetry) is a 5th year Senior from Raleigh, North Carolina, and he has had the honor of being rejected from all sorts of esteemed literary publications in the past (including LQ). He will show you pictures of his dog, Cody, both prompted and unprompted.

Sijia Ma (visual Art) (b. 2001 in Shenyang, China), is a visual artist based in Shanghai and Massachusetts. She is currently pursuing a B.A. in Studio Arts and Quantitative Economics at Smith College, MA. She also studied Photography at Amherst College in 2020. Sijia has worked to develop image-based projects and used the language of photography to explore the complexity of today’s Chinese identity in a subtler way.

Aden McCracken (he/him) (poetry, visual art) is a freshman studying Psychology with a concentration in Health and Development, while also minoring in Creative Writing. His passion for advocacy and awareness bleeds over into his art through his external reflections of his identity as a COSA (child of substance abusers), recovering alcoholic, and low-income, first-generation student.

Chaidie Petris (poetry) is a Greek-American poet and a sophomore at Stanford University. Their work has recently been published in Stanford’s Leland Quarterly and the Eunoia Review, and will appear in The Blue Route this coming spring. In the tradition of the Beats, their work is often inspired by their travels and conversations with members of oppressed classes in America.

Danny Ritz (prose) is a junior from Rydal, Pennsylvania. He isstudying English (Creative Writing) and Music.

Isabella Sarraco (poetry) is a junior studying History and Creative Writing. Born and raised in Chicago, she is interested in folklore, gender and sexuality, and chinchillas. She wants to get a PhD to become a history professor. In her free time, she enjoys reading, writing, and spending time with her friends.

Nur Shelton (visual art) is a Junior from Ashland, Oregon. He spends his time at Stanford climbing at the rock wall, tap dancing, exploring the Santa Cruz Mountains, and studying English.

Anna Zheng (prose) is a freshman originally from Atlanta, Georgia, where she enjoys writing bad poetry and marginally less bad short fiction. She has previously been published in Sandpiper. She is not sure what she’s doing.

Where do you want to see LQ head in the future? How can we continue to grow, increase our accessibility, and support the artistic community at Stanford?

We would truly appreciate your input. If you have five spare min utes, please take this survey and share your ideas with us: