Featuring Miles Howard-Wilks, Dionne Canzano, Patrick Francis, Bronwyn Hack, Ruth Howard, Michael Camakaris, Julian Martin, Terry Williams and more

Curated by Miles Howard-Wilks, Sandy Fernée and Sarah Lamanna

25 MAY — 6 JULY

ARTWORK: Miles Howard-Wilks Untitled 2023, glazed earthenwareWelcome to the June-July issue of Leonard Magazine.

Within this issue, to celebrate the Year of the Dragon, we learn about the dragon motif in traditional Chinese art through history. We also take a look into the jewellery box of the Duchess of Windsor, discover what edition markings mean on prints, learn about "the dirty dozen" - the holy grail of military watch collecting, explore the role of technology in contemporary art, and more.

We hope you enjoy.

cover:

A Chinese embroidered blue-ground ‘Dragon Robe’, Mangpao, Qing dynasty (1644-1911)

$5,000-$7,000

Fine Chinese and Asian Art Auction 25 August, 11am

below:

18ct gold diamond and sapphire pendant earrings

$2,800-3,800

Fine Jewels Auction 24 June, 6pm

June–July 2024

features

The Intersection of Technology & Art

The Vogue for the Loge: Painting the Theatre Box

The Dirty Dozen: as Legendary as the Cinema Classic

Beyond Priceless: Wallis Simpson’s Jewellery Collection

Inspiration & Imitation: Appetite & Appropriation of Exotic Porcelain

The Year of the Dragon (Long): Depictions in Chinese Art

Beyond Functionality: Forms & Figures

On our Nature (Strip)

What is it Really Worth?

Fifty Shades

Hot off the Press: A Guide to Prints & their Editions

in focus

Five Minutes with Millie Lewis

22nd Report: Gripping Docuseries Examines Shadowy World of Elephant Poaching in India

Thinking of Selling?

A Last Look

join us

Connect Value, Sell & Buy

July

The Auction Salon

The Collector's Auction

Tue 4 Jun, 2pm

Sydney

The Sydney Jewellery Edit Wed 5 Jun, 2pm

Sydney

The Collection of the late Patricia Begg OAM Mon 17 Jun, 2pm

Melbourne

Timepieces Mon 24 Jun, 4pm

Melbourne

Fine Jewels Mon 24 Jun, 6pm

Melbourne

Fine Art Tue 25 Jun, 6pm

Melbourne

The Online Collector Wed 26 Jun, 2pm

Sydney

Modern Design Mon 15 Jul, 6pm

Melbourne

Luxury Tue 16 Jul, 6pm

Melbourne

Prints & Multiples

Wed 17 Jul, 6pm

Melbourne

Furniture & Interiors, Objects & Collectables, Jewellery, Art

Every Thu from 10am

Melbourne

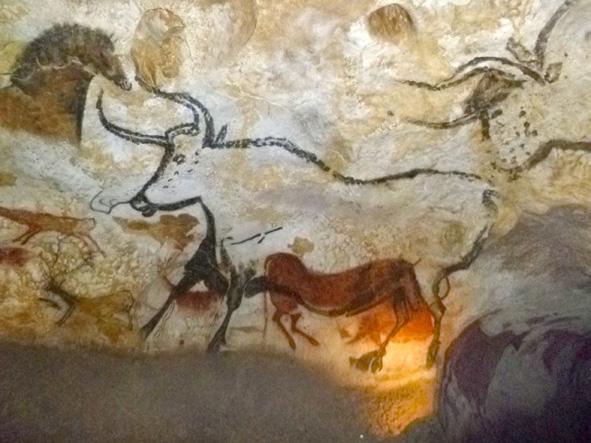

From the early cave paintings in Lascaux to the marble masterpieces of ancient Greece, art has served as a timeless mirror reflecting the human experience and cultural evolution.

by wiebke brix, head of art

throughout history, artistic mediums have encompassed tangible materials and craftsmanship. Whether it is the intricate brushwork of Rembrandt or the sculptures of Michelangelo, physicality has been central to the way artists work. Even “cultural resets,” such as Duchamp’s introduction of the ready-made concept, expanded artistic possibilities while still being rooted in tangible materiality.

As we navigate the complexities of the digital age, the definition of art broadens to incorporate intangible and interactive elements. The emergence of video art in the late 1960s marked an initial attempt to merge technology with artistic expression, but the result was often rudimentary and struggled to captivate. As society progresses into a technology-dominated era, the intersection of art and technology becomes an increasingly vital commentary on our world.

Recent exhibitions, such as those by Agnieszka Pilat and the experimental art collective Marshmallow Laser Feast, signify a shift in the relationship between art and technology. Pilat’s installation Heterobota, featured in this year’s Triennial at the National Gallery of Victoria, challenged conventional creativity by employing Boston Dynamics robot dogs as painters. These mechanised artists, roaming freely and creating abstract compositions, provoked profound questions about the intersection of technology and humanity. As viewers witnessed the robotic dogs engage in the act of creation, they were compelled to confront how technology shapes our lives and perceptions, blurring the boundaries of art, technology, and humanity.

Similarly, Marshmallow Laser Feast’s exhibition, Works of Nature, showcased at ACMI, transcends traditional artistic boundaries by immersing viewers in a sensory journey exploring the interconnectedness of nature, the human body, and the universe. Through large-scale screen works, interactive experiences, and guided meditations, the exhibition invites audiences to contemplate the sublime forces governing existence.

What distinguishes these exhibitions is not merely their use of technology but their ability to use technology as an artistic expression that is captivating and relevant. By seamlessly integrating tech with tra-

ditional artistic elements, they offer a glimpse into a future where art becomes a dynamic dialogue between the old and new, traditional and technological media.

These exhibitions succeeded in reflecting contemporary society, which in my opinion is integral to important art. In an age defined by rapid advancement and societal transformation, the fusion of art and technology becomes a powerful tool for documenting and interpreting the world around us.

The convergence of technology and art represents a new frontier in creative expression. By pushing the boundaries of traditional mediums and embracing innovative technologies, artists redefine what it means to create and experience art. Installations such as those by Pilat and Marshmallow Laser Feast embody a refined approach, transcending the rudimentary to engage us and to offer a meaningful dialogue on the roles of technology in our lives.

This exploration has traversed a remarkable journey from the early video works of the 1960s to the immersive digital experiences of today. What once may have felt experimental has evolved into sophisticated expressions that entrance and engage audiences on profound levels.

This development is important not only to keep the artistic expression relevant but also to cultivate a new generation of art lovers and collectors. In an age where technology permeates every aspect of our lives, it is exciting to see how new media produces work that is not only relevant but also resonates, allowing viewers to connect with art in new ways.

As artists continue to push the boundaries of what is possible at this intersection, the future of artistic expression holds endless possibilities, ensuring that art remains as important as it always has been.

left:

Art has always reflected the human experience. Over 600 paintings cover the interior of the Lascaux cave in France, dated to 17,000 years old. The paintings show animals of the Paleolithic Age that were living in the area at the time.

top:

Distortions in Spacetime by Marshmallow Laser Feast, Works of Nature, ACMI, 2023, image by Eugene Hyland

top:

Distortions in Spacetime by Marshmallow Laser Feast, Works of Nature, ACMI, 2023, image by Eugene Hyland

left: § Jean-Gabriel Domergue (1889-1962)

La Loge

left: § Jean-Gabriel Domergue (1889-1962)

La Loge

opera, coming from the italian word for labour/work, realised the Baroque ambition of integrating all the arts. Music and drama were the fundamental ingredients, complemented by staging and costume design. It’s no wonder then, with this intertwining of disciplines, that opera was frequently documented by fine artists in paintings, drawings, and printmaking. This practice was particularly prevalent in France, where the genre was to dominate the stage evolving into romantic grand opera by the turn of the 19th century. Opera as an art form has been considered intrinsic to French culture ever since.

French opera tradition dates back as far as 1673 with a performance of Jean-Baptiste Lully’s Cadmus et Hermione performed at the court of Louis XIV of France. By the end of the 18th century, opera had become an international phenomenon and had generated several genres, both comic and serious. In the 19th century, the growing wealth and influence of the bourgeoisie in France began to broaden the audience for opera and result in changes to the form itself.

Opera became more accessible to a wider audience and a bigger part of everyday life for the upper-middle class. Where historically it had been the domain of the nobility and aristocracy, there was now an opera for almost everyone in French society to attend. By the mid-19th century, the Opéra was considered the theatre for the aristocracy and the nouveau riche, the Opéra-Comique that of the bourgeoisie, and the Théâtre-Lyrique stood as the opera house for the working man and woman and the hard-up artist. Towards the end of the century, however, these lines began to blur much to the unease of the upper-class who were increasingly uncomfortable at the Opéra due to the increased numbers of bourgeoisie attendees.

During the late 19th century, the opera became not only a place to watch a performance but also a social gathering where high society would mingle and show off their latest fashions. It also served as one of the only social settings that women could freely attend. These changes in the audiences were reflected not only in the prosperity of the operatic arts but also depicted by the artists of the time. Whilst historically artists had depicted narrative scenes from the operas themselves, they began portraying audi-

ences in the act of watching the opera. The artist’s gaze shifted from the stage to the boxes, and the observers became the observed.

The subject of the loge, or theatre box, was one that was favoured by the Impressionists as it fulfilled their desire to depict the spectacle of modern life. In 1874, Pierre-Auguste Renoir exhibited La Loge (The Theatre Box) at the first Impressionist group exhibition in Paris to much critique. Whilst some admired Renoir’s new subject matter and his painterly technique, several reviewers were troubled by the main subject. Their primary contention was that the central female figure appeared not to be a respectably married member of fine society but rather that her extravagant dress and made-up face alluded to her being a high-class courtesan.

Shortly after, in 1878, artist Mary Cassatt painted In the Loge (also known as At the Opera) which again takes a central female figure as its primary subject. Cassatt’s woman plays a more active role in the composition, depicted engaged in watching the opera whilst a man from another box in the distance turns his gaze away from the stage to look at her. Renoir by comparison approached his female subject with a direct gaze in order to display her physical features more prominently.

The opera box continued to be a source of fascination for artists throughout the 20th century, featured in works by artists such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jean-Gabriel Domergue, Jean Beraud, Charles Henry Tenré, and more. Aside from the natural frame that the theatre box provides, it also offers opportunities to explore a variety of themes such as the relationship between appearance and reality, and the confluence of public and private space. The artist can capture a sitter who is conscious of both watching and of being watched and at the same time present to us a little slice of Parisian life.

The Collector's Auction will take place on Tuesday 4 June in Sydney. For viewing times and to see the full catalogue please visit our website.

left: Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) La Loge (The Theater Box)

left: Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) La Loge (The Theater Box)

For most people, the words “The Dirty Dozen” immediately call to mind Robert Aldrich’s genre defining World War II epic starring Hollywood hard boiled tough guys Lee Marvin, Charles Bronson, and Telly Savalas. But in the watch collecting world, this is a nickname that refers to a group of 12 watches worn by British soldiers who actually fought in the war.

by patricia kontos, senior timepieces specialist

military watches that make up the Dirty Dozen are many a collector’s coveted dream and when an elusive full set appears on the market it can sell for incredible sums, not least because of the military history and scarcity that surrounds it. Let’s delve a little deeper into how this influential collection of field watches helped British soldiers win the war and earn their very cool sobriquet.

Turning back the clock to 1914, we saw the demands and rigours of the First World War battlefields sound the death knell for the pocketwatch. They persisted in civilian life, but on the battlefield a soldier didn’t have the luxury of extracting a watch from his pocket. If he had to tie up one hand in the operation of a pocketwatch to determine the distance of incoming artillery fire whilst loading a rifle, that lost moment could cost him his life. Initially, the trend was for soldiers to strap their pocketwatches to their wrists for easier and quicker access. Eventually, soldiers would be issued “trench watches” made with pocketwatch movements, with the crown usually at 12 o’clock and luminous indices, but most importantly, they could be worn on leather straps keeping their hands free and allowing for accurate coordination of military manoeuvres.

While these trench watches effectively served their purpose, the advent of another war barely two decades later would make the demand for the “perfect soldier’s watch” as distinct from repurposed civilian watches, increasingly pressing. The edict from the British Army, Air Force, and Royal Navy stipulated that military timepieces were to meet strict specifications such as: a black dial, Arabic numerals, railroad style minute track, luminous hands and minutes, chronometer grade 15-jewel manual wound movement, shock and water-resistant type case and crystal, fixed lugs, and a larger crown for use with gloves.

For the duration of WWII, British manufacturing had focused its production to goods directly beneficial to the war effort. With the British watchmaking industry now depleted, the Ministry of Defence (MOD) approached the following 12 Swiss watch manufacturers to produce dedicated field watches to equip their specialists and soldiers: Buren, Cyma, Jaeger-LeCoultre, Lemania, Longines, IWC, Omega, Record, Timor, Vertex, Eterna, and the most famous brand on the list, Grana. These Swiss based manufacturers answered the MOD call producing military precision watches with case backs stamped W.W.W. (“Watch, Wrist, Waterproof”), a capital letter and five-digit serial number, along with the Broad Arrow emblem that was steeped in British heraldry and traditionally used to denote UK Government property.

With the end of the war came the diminished demand for military watches and for the next couple of decades they were unassumingly referred to as “Watches, Wrist, Waterproof” as per their W.W.W. caseback initials. However, when in 1967 Robert Aldrich’s WWII blockbuster hit the screens to massive commercial success, the tough guy title caught on and the nickname “The Dirty Dozen” was affectionately applied to this group of watches - and don’t watch collectors love a nickname.

It is fair to say the story of the Dirty Dozen has entered horological lore and the fascination with these functional and efficient tool watches has not waned. Not only are they regarded with reverence for aiding British soldiers in winning the war, but they also provided the template for many field watches that followed. Notable watches from this set such as the limited issue Grana are met with a flurry of excitement when they appear on the market, and for a complete set to come up, well, here you might say we’re approaching holy grail territory.

Leonard Joel will offer An Important Private Collection of Military Watches including a complete Dirty Dozen in our forthcoming Timepieces Auction.

Our Timepieces Auction will take place on Monday 24 June in Melbourne. For viewing times and to see the full catalogue please visit our website.

the romance between King Edward VIII and the American divorcée Wallis Simpson stands out as one of the most captivating and controversial love stories of all time. The Duchess of Windsor’s jewellery collection is equally unparalleled. It boasts not only jewels personally selected by a king for the woman he abdicated the British throne for, but also showcases some of the most exquisite designs from renowned 20th century jewellers.

Her impeccable taste in fashion and jewellery radiated glamour, cementing her status as an icon for designers both during and after her lifetime. As a prominent figure in high society, the Duchess of Windsor cultivated relationships with the elite of the fashion world. This resulted in numerous bespoke gowns crafted especially for her to showcase her jewels, by iconic designers like Elsa Schiaparelli and Christian Dior.

Never one to follow trends, her choice of engagement ring was less than conventional. The Duke of Windsor proposed with a dazzling 19.77ct emerald ring crafted by Cartier. Jacques Cartier reported that the gem was one of two stones cut from an emerald as large as a bird’s egg that once belonged to a Grand Mogul. It was also inscribed on the platinum shank with a hidden message “We are ours now 27 X 36”. The date was significant as it referred to the day, month, and year of the beginning of Simpson’s divorce proceedings from Ernest Simpson. These hidden messages became a recurring motif within the couple’s jewellery.

When the prime minister, the press, and the public learned about the king’s desire to marry an American woman soon to be twice divorced, it became a national crisis. The pressure was so intense, that the king decided to abdicate. In his radio address to the nation on December 11, 1936, he said, “I have found it impossible to carry the heavy burden of responsibility and to discharge my duties as king as I would wish to do without the help and support of the woman I love.” This decision changed the line of succession and ultimately saw Elizabeth II on the throne 17 years later.

Among the Duchess of Windsor’s collection of jewellery were her iconic ‘Great Cat’ pieces commissioned from Cartier. Jewellery often communicates when words fall short. The leopard belongs to the Panthera genus,

known as the Great Cats. What sets these cats apart is their unique ability to roar, rather than purr. One of her first “Great Cat” acquisitions was the sapphire and diamond panther brooch, crafted by Cartier in 1949. The majestic feline on this brooch is depicted in a lifelike crouch, as if poised to leap over the moon, adorned with a large, perfectly round cabochon star sapphire weighing 157.35 carats. Yet, it’s the legendary panther bracelet that holds a special place of honour in her collection. To this day, the bracelet boasts the world record for the most expensive bracelet ever sold at auction (£7.4 million in 2010) and it was even rumoured at the time that the buyer was Madonna.

Edward VIII showered the love of his life throughout their marriage with the finest jewels. Indeed, so obsessed was he with Wallis, he insisted the Duchess of Windsor’s collection of jewels be dismantled after her death. Edward VIII was determined that no other woman would ever wear them. However, the former King of England was not to have his way. In 1987, Around 1,000 bidders crowded into a huge tent erected by Sotheby’s next to Lake Geneva for the two-day sale. The Wallis Simpson Jewellery Collection consisted of 214 pieces and sold for the record price of $53.5 million. The Duchess of Windsor’s jewels were unique, not only because of the record prices they fetched but also since these pieces immortalise the most controversial love story of modern times.

opposite: The Duke of Windsor and Wallis Simpson on their wedding day, 1937, Chateau de Cande, Monts, France / Alamy

right: The Duchess of Windsor wearing her Cartier emerald engagement ring, 1936 / Alamy

opposite: The Duke of Windsor and Wallis Simpson on their wedding day, 1937, Chateau de Cande, Monts, France / Alamy

right: The Duchess of Windsor wearing her Cartier emerald engagement ring, 1936 / Alamy

Although seaborne trades had been active for centuries, it was not until 1602 when the Dutch East India Company was founded that a monopoly on trades in the far east occurred.

by chiara curcio, head of decorative arts, design & interiors Hendrick Cornelisz Vroom (1562/1563–1640)

Hendrick Cornelisz Vroom (1562/1563–1640)

the dutch east india company (commonly known as the VOC: Verenigde Oost-Indische Compangnie) developed trade routes and established the Batavian entrepôt for silks, spices, and porcelain wares. The VOC had vast commercial interests and enjoyed a monopoly in the trade to and from India and the East, resulting in large sums of Asian porcelain reaching European and British shores, and satiating the demand for delicate porcelain wares with foreign designs. The increased export of Chinese wares led to the broader influence of Chinese design, captivating the western world with its mystery and charm. This enthusiasm for and appropriation of Chinese design was so prolific that the term ‘chinoiserie’ was coined to identify it.

Colloquially known as the porcelain capital of China, Jingdezhen is a province synonymous with porcelain since the Song Dynasty, having produced imperial wares since the 6th century. Mastering their craft over hundreds of years, the Chinese had established advances in porcelain techniques and decorations over their foreign counterparts, making their pieces very desirable and resulting in European copies of Chinese styles.

The Derby plate, dating to 1760, is an English example of chinoiserie, featuring a Chinese pagoda in landscape scene, all in underglaze blue, the cavetto decorated with a basketweave border with alternating insect designs. Blue and white wares, unlike tin glazes that were preferred in the 16th century, gained popularity due to their fine execution and interesting designs that included botanicals, landscape scenes, auspicious symbols, and mythical creatures.

By the early 17th century, political unrest in China and the Manchu invasion disrupted the porcelain production at Jingdezhen. During this time, Japan was implementing their sakoku (closed country) policy, prohibiting foreigners entering Japan and the nationals leaving. Leveraging their foreign power, the VOC negotiated entry into Japan, being the only Europeans to achieve this, and establishing an alternate supply from Japan to fill the trade demands.

Japanese porcelain was produced at the Arita kilns, where until that point porcelain wares were made solely for local consumption. By the end of the century, Arita was catering predominately to export demands, which consisted of blue and white, Imari, and kakiemon wares. Imari and kakiemon were unlike the familiar blue and white porcelain of the period, charming the West with their bold colours and asymmetrical designs sitting predominately against the pure white porcelain ground.

These porcelain patterns were highly prized and meticulously copied, and by the 18th century the Europeans and then the English developed their own interpretation of kakiemon and Imari decoration, encapsulated by this dessert bowl by Worcester, decorated in the bold palette of kakiemon design, dating to 1765.

These interesting porcelain pieces feature in our forthcoming single owner auction, The Collection of the late Patricia Begg OAM.

Patricia was a heavyweight of the porcelain world, contributing to education and philanthropy, and raising over $700,000 for charities through lectures concerning ceramics, glass, and lace. Internationally, Patricia was a respected member of the English Ceramic Circle, the Oriental Ceramics Society, The French Porcelain Society, and the Northern Ceramics Circle in England. Closer to home, she was not only a member of the Ceramics and Glass Circle of Australia, but the president until her passing in 2019, and a founding member.

In 2002, she received an Order of Australia for her work in aged care through the Uniting Church in Australia, music through the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, and the decorative arts via the Ceramics and Glass Circle of Australia. In 2006, Patricia and her daughter Anne McNair were tasked to assist in the completion of the Catalogue of the Lady Ludlow Collection of English Porcelain at the Bowes Museum, England. Published in 2007, this remains a core reference on English ceramics.

This collection comprises her remaining works that were not donated to the National Gallery of Victoria, a good and broad cross section of European, English, Japanese, and Chinese porcelain from the 17th-21st centuries.

Her love and deep understanding of porcelain history, technique, and design is best captured by a quote, “The marriage of the potter and the painter produce individual and unique pieces for posterity.”

The Collection of the late Patricia Begg OAM Auction will take place on Monday 17 June in Melbourne. For viewing times and to see the full catalogue please visit our website.

$300-500

Circa 1765

$300-400 above: Job Adriaenszoon Berckheyde (1630-1693)

The Courtyard of the Stock Exchange, VOC Headquarters, Amsterdam, between 1670 and 1690 / Amsterdam Museum

in the chinese lunar calendar, the year 2024 is known as the Year of the Dragon, or ‘Long’ (龙). In Western contexts, the dragon is a fearsome, fire-breathing beast that often symbolises danger or malevolence (like in the story we can see illustrated in the ancient Greek vase by Douris, for example). In traditional Chinese culture however, the dragon holds fundamentally different connotations.

The idea of the Chinese dragon ‘Long’ originated in the Neolithic era. One of the earliest images of a dragon discovered in China is the green jade ‘C’ shaped dragon from Hongshan culture (c. 4700 to 2900 BC). It is finely carved from dark green Xiuyan jade and has the reputation of being the first, and the best, dragon of China.

The depictions of ‘Long’ changed during the Bronze Age, around the first millennium BC. Initially resembling stylised versions of real animals, they evolved into mythical creatures; powerful, serpentine figures with deep symbolic meaning. Bronze vessels from this time frequently depicted elaborate scenes of dragons, highlighting their revered position in early belief systems.

Following this period, the image of ‘Long’ took a more devotional turn. The dragon held a revered status, helping to communicate between the realms of heaven and earth. Unearthed in 1977 from a tomb dating back to the Warring States period (475-221 BC) in Anhui Province, were three similar pendants in the form of dragons. They were positioned symmetrically on either side of the pelvic bones, suggesting that they formed part of a set worn by the tomb’s occupant that symbolised an aspiration for everlasting life beyond death. The fact that the pendants were exceptionally well-preserved and meticulously crafted also shows the high status of the individual interred in the tomb.

As Buddhism took root in China, its artistic imagery underwent a transformation to resonate with Chinese cultural norms. Gradually, the figure of ‘Long’ assumed the role of a protective guardian, with artwork of this time often illustrating the dragon safeguarding the Buddha.

From the Han dynasty onward, the most acknowledged symbolic meaning of ‘Long’ was that of imperial authority. Beginning with Emperor Liu Bang (reigning from 202-195 BC) who claimed his conception was linked to a dragon encounter by his mother, this majestic creature gradually evolved into a potent symbol associated with rulership. Emperors adopted the title ‘heavenly son of the real dragon,’ while images of dragons embellished palaces, imperial furniture, clothing, and daily utensils.

From the mid-Ming dynasty (15-16th century) to the end of the Qing dynasty (20th century), the five-clawed dragon was the symbol of the emperor, for everlasting prosperity and the continuity of the empire.

The close connection between dragon motifs and imperial authority can also be found in the strictly controlled court attire system, especially in the Qing dynasty. By the regulation announced during the Qianlong period (17361795), bright yellow garments with a five-clawed dragon rank badge (Buzi) were exclusively reserved for the emperor and empress. Lower-ranked members of the imperial family were entitled to wear robes with the rank badge of a five and four-clawed serpent, or without a rank badge but still adorning their ceremonial robes with the motif, as seen in a beautiful, embroidered robe to be offered by Leonard Joel later this year.

As illustrated in these examples throughout history, in Chinese culture, no mythical creature is more revered than ‘Long.’

Our Fine Chinese and Asian Art Auction will take place on Sunday 25 August in Melbourne. For viewing times and to see the full catalogue please visit our website.

opposite: A Chinese embroidered blue-ground ‘Dragon Robe’, Mangpao, Qing dynasty (1644-1911)

$5,000-$7,000

left: Douris was an Athenian red-figure vase-painter and potter active c. 500 to 460 BCE. This vase shows Jason being regurgitated by the dragon who keeps the Golden Fleece (center, hanging on the tree); Athena stands to the right. Red-figured kylix, c. 480–470 BC. From Cerveteri (Etruria)/ Vaticans Museums

right top: A Chinese Hongshan ‘C-shaped’ ‘dragon’ pendant, Neolithic period, Hongshan culture (47002900 BC), National Museum of China / Alamy

right bottom: Blue and white dish depicting the five-clawed dragon

anthropomorphism and zoomorphic design have been prevalent themes in the 20th century, deeply rooted in the intersection of culture, history, and design philosophy. These concepts, drawing inspiration from both human characteristics and animal forms, have shaped various aspects of design, from architecture to industrial and commercial product design.

Some of the earliest examples of anthropomorphism and zoomorphic design can be traced back to ancient civilizations. The Egyptians, for instance, depicted their gods with human bodies and animal heads, blending human attributes with animal symbolism. This fusion of characteristics reflected their beliefs, where animals were revered for their perceived qualities such as strength, wisdom, or agility.

Fast forward to the 20th century, and these themes experienced a resurgence, particularly in the wake of industrialisation and technological advancements. As society grappled with the rapid changes brought about by modernity, there was a longing for a connection to nature and a desire to imbue the sterile, mechanised world with warmth and personality; a playful contrast to modernism while still often loaded with meaning, references, and symbolism.

Here are a couple of my favourite designers from the second half of the 20th century whose work incorporates these themes.

Nicola L.’s work engaged with radical ideas in feminist politics, equality, and collectivity. She was particularly known for her anthropomorphic designs that fused the female form and domestic objects. She termed much of her sculpture “functional art,” making furniture that is at once silly, critical, and useful. La Femme

Commode, originally designed in 1969, is a lacquered wood cabinet in the shape of a woman in which body parts become drawers.

Many of Gaetano Pesce’s designs incorporated anthropomorphic elements. One of the most well-known examples would be his La Mamma chair and ottoman designed in 1969, part of the UP series produced by B&B Italia. Of feminine form inspired by silhouettes of ancient fertility goddesses and accompanied by an affixed ottoman resembling a ball and chain, this piece is both practical and radical.

French sculptors Claude and François-Xavier Lalanne, known collectively as Les Lalanne, challenged the boundaries between art and design. Their zoomorphic furniture designs are highly decorative yet also functional. A bronze Hippopotame II bar from 1978 recently sold at Christie’s for over 7,000,000 USD. As the name suggests, it is indeed a life-sized hippopotamus shaped bar. Les Lalanne are also well known for their whimsical sheep shaped sculptures that function as stools. These are just two examples of many marvellous, sought after creatures in their oeuvre.

opposite: Gaetano Pesce UP 5 lounge chair and UP 6 ottoman for B&B Italia Sold for $6,875

opposite: Gaetano Pesce UP 5 lounge chair and UP 6 ottoman for B&B Italia Sold for $6,875

one of my earliest memories while walking the neighbourhood as a young boy was the sight of hulking old wood-framed radios out on the nature strip, ready for collection. In essence, they were making way for the arrival of colour television, and more broadly, the unstoppable miniaturisation of every form of consumer electronics. The valves in these old radios fascinated me as did those other things that households no longer had a purpose for or a market within which to on-sell them. I also remember seeing old soda syphons and their little chargers; they too intrigued me.

The term “hard waste,” as these moments in the life of a household have come to be known, is an incongruous one in the world of collecting. They should rather be called “nature strip days,” or “changing taste days,” or “changing technology days,” for this is what they are a mix of. And I won’t lie, I continue to find them fascinating because for me they remain somewhat of a barometer for collecting, living habits, and the nature of design.

The lonely Victorian balloon-back chair or the inter-war piece of furniture is now not an uncommon sight as one drives around residential streets. Now, it would be unheard of to find an item of used luxury in these gatherings of the unwanted, just as a well-known make of designer furni-

ture would rarely be found here. These are the things that are now very much in vogue, and coveted by those whose sweet spot is post-retail. Once upon a time, they would either have been gifted to friends and family or indeed waiting for collection on these “nature strip days.”

I was recently comforted to know that it was certainly not just me that found this element in the life cycle of collecting and domestic life intriguing, when I spotted a client of mine, just after dark, and at a brisk walking pace, carrying away from one of these offerings a brass platter he had found! I didn’t stop to congratulate him for fear of embarrassing the situation. It was a silly little moment that described how these days can reflect and describe our natures and our lifestyles in curious ways.

Image:

Niels Gammelgaard

of

when it comes to jewellery valuations, it can seem like navigating a minefield. Clients are often perplexed when they come to Leonard Joel for estimates on their jewellery and our quotes fall below their expectations. There is a common myth that a jewellery valuation is used to indicate the ‘worth’ of an item, however there are many types of valuations, and they all serve different purposes.

The most common is an insurance valuation, the purpose of which is to determine a cost for replacing like for like in the event of loss or damage. A qualified valuer uses specialised gemmological equipment to determine gem weights, gold carat levels, and metal weights, and they also consider manufacture costs and the condition of the item to determine a value.

Generally speaking, an insurance valuation is typically 10-15% above the purchase price. Factored in is a buffer for future fluctuations in the market, for example metal prices, exchange rates, and interestingly, fashion trends. It is important to note that insurance valuations are not used in determining retail pricing.

Bricks and mortar retailers have different replacement values given the variance in their costs and overheads. Some prefer to issue Certificates of Authenticity, this is usually stated as the price for which the item was purchased. These documents are of particular importance when purchasing branded jewels such as by Cartier or Tiffany & Co. If you decide down the track to sell, it gives peace of mind to potential buyers that the item is genuine.

Next, we come to auction value. Here at Leonard Joel, our jewellery specialists hold industry recognised qualifications in gemmology, diamond grading, and valuing. Our locations are equipped with gemmological tools used to identify and assess your jewellery. The specialists keep abreast of local and international auction results and trends to determine a range in which they think the hammer price for a lot at sale is likely to be. For the secondary market, values are typically between one third and a fifth of the insurance or retail replacement value of a jewellery item. Our aim is to be transparent and realistic in our estimates, and the hope is to generate interest and competition on auction night to achieve great results!

Circling back to ‘what is it worth,’ at the end of the day, a piece is worth what someone is prepared to pay. As eloquently put in the 1997 classic The Castle, Dale asks, “How much is a jousting stick worth, Dad?” To which Daryl responds, “Couldn’t be more than $250. Depending on the condition.”

Image: Rebecca SheahanFew accessories possess the transformative power of sunglasses, serving as an entry point for many into the coveted world of high-end design or invaluable collector’s items.

by indigo keane, luxury specialist

from kurt cobain’s 1990s oval Christian Roths to Delfina Delettrez Fendi’s Fendi Couture diamond studded spectacles, these accessories stand for more than mere adornment; sunglasses possess the ability to completely alter one’s appearance, framing the face, accentuating features, and sometimes acting as a shield between oneself and the world. These iconic accessories have journeyed through history, reflecting the styles of their times while maintaining an enduring status as indispensable fashion statements and must-have essentials. From ancient origins to modern runways, the story of sunglasses is a fascinating exploration of style, innovation, and cultural influence.

The origins of sunglasses can be traced back to ancient civilizations. In 12th century China, flat panels of smoky quartz known as Ai Tai were utilised to obscure the expressions of magistrate judges in court. The Inuit people of the Arctic fashioned goggles from walrus bone and wood to shield their eyes from the blinding reflection of snow. In Venice, the iconic Goldoni glasses shielded gondoliers from the glaring sun bouncing off the city’s picturesque canals. In ancient Rome, Emperor Nero peered through polished emeralds to watch gladiator matches, foreshadowing the luxury eyewear of modern times. These early iterations of sunglasses laid the groundwork for the stylish and functional eyewear we enjoy today.

In the 1920s, with the rise of Hollywood cinema, sunglasses began to gain popularity among actors and actresses seeking to shield their eyes from bright studio lights. Stars like Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich helped popularise sunglasses as symbols of glamour and mystique.

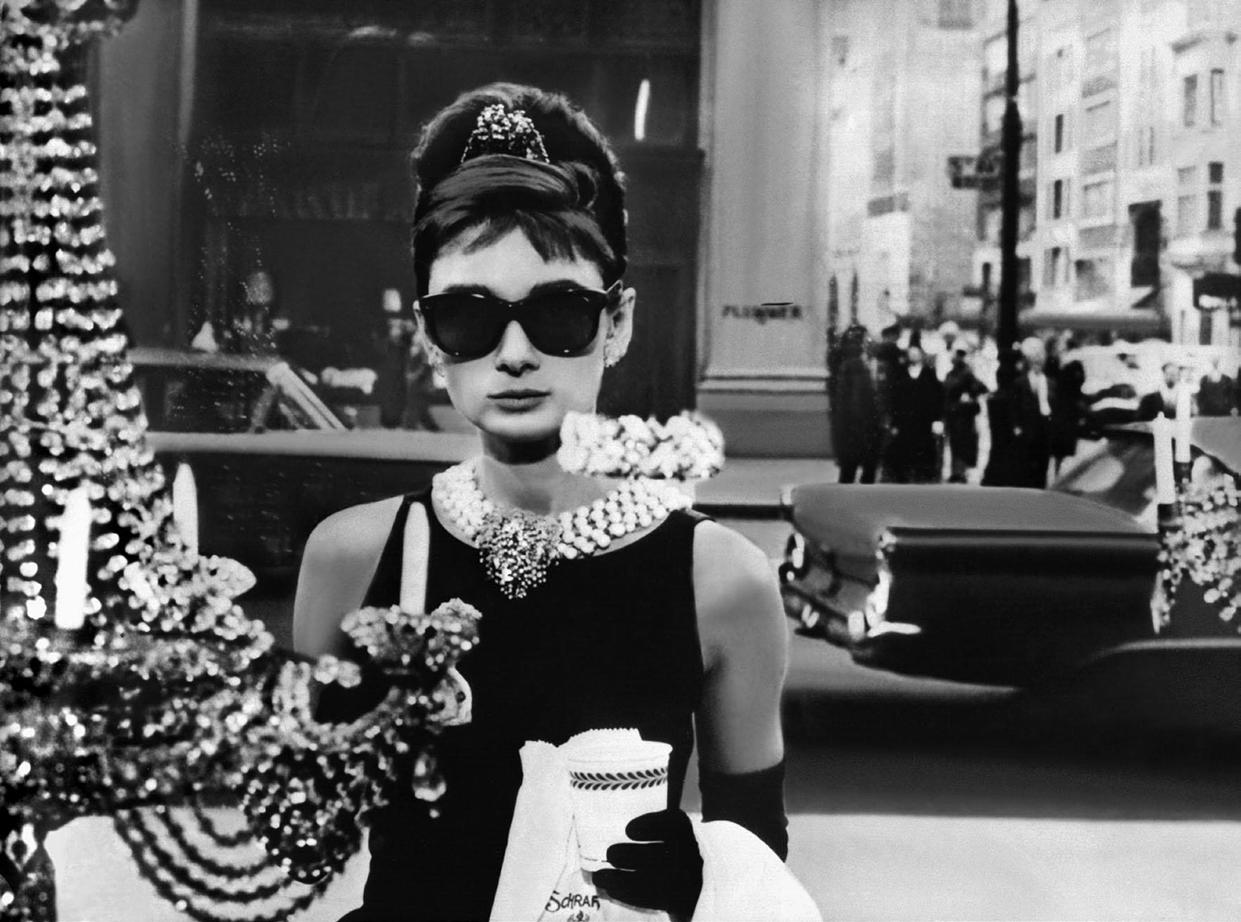

The mid-1930s heralded the inception of aviator glasses, originally designed for military pilots, with Ray Ban pioneering the utilisation of polarized lenses. They have been reimagined by Tom Ford and Phoebe Philo, offering sleek interpretations that blend retro charm with a bold and contemporary vision. The 1950s and ‘60s marked a turning point for sunglasses in fashion. Iconic figures like Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s and Marilyn Monroe epitomised elegance with their oversized shades and cat eye sunglasses.

The influence of sunglasses extends beyond aesthetics. Innovations in lens technology, such as polarized and photochromic lenses, ensure that modern eyewear not only complements style but also enhances functionality and comfort.

The history of sunglasses is a testament to the dynamic relationship between fashion and functionality. From their humble beginnings as protective eyewear to their current status as indispensable fashion accessories, sunglasses have continuously evolved, reflecting the ever-changing tastes and attitudes of society.

As we continue to celebrate the legacy of iconic designs and embrace new innovations, one thing remains certain: sunglasses will always be a symbol of self-expression and a nod to fashion evolution.

opposite left:

Kurt Cobain, 1998 / Alamy

opposite right:

Bottega Veneta, pair of sunglasses

Sold for $562

opposite left:

Kurt Cobain, 1998 / Alamy

opposite right:

Bottega Veneta, pair of sunglasses

Sold for $562

Have you ever wondered about the significance of an ‘edition’ on a print?

by hannah ryan, prints & multiples specialist

the figures you may see in the bottom corner of a print indicate the total number of prints made from a single plate. Two primary categories exist: limited and open editions. Limited editions are exclusive, with a fixed number of prints created, enhancing their desirability and value. Each print is meticulously marked to indicate its position in the series. On a print from an open edition, you would not find an edition number. However, there is a deeper layer to uncover. We are delving into the technical nuances of editions, essential for navigating the complex landscape of the art world. Prepare for an enlightening journey into the realm of printmaking…

what constitutes an edition?

Each individual artwork (whether a print, sculpture, or photograph) within a series is often referred to as an ‘edition’, illustrating that it is part of a collection of identical artworks.

numbered print

The numbering of a print takes the form of a fraction and is often found with the artist’s signature. It represents the print number as well as the total number of prints in the edition. For instance, 5/20 indicates that the print is number five out of a limited edition of 20.

uneditioned prints

There are some prints that are considered as ‘open editions’ or uneditioned, that do not bear an edition number. This can be due to various reasons, including the artist’s preference and the nature of the artwork. These prints are often well-documented to solidify their authenticity.

bat: bon à tirer

BAT is the acronym for ‘bon à tirer’, a French expression meaning ‘good for printing’. It signifies the final proof of a print approved by the artist, serving as a guide for the rest of the edition to replicate. Since there is typically only one of these proofs for an edition, the print technician traditionally retains it.

h/c: hors d’commerce

Hors d’Commerce is a French phrase signifying ‘not for sale’. A H/C proof resembles an Artist’s Proof in being identical to the final edition. Historically, H/C proofs were intended for the artist and their collaborators, hence the instruction that they are not to be sold. However, in practice, these proofs are frequently retained with the rest of the proofs.

a/p: artist’s proof

Artist’s Proofs are often marked with A/P or the French version E/A (Epreuva d’Artiste). This edition indicates that both the artist and print technician are satisfied with the progress, ready to commence the next steps of the official run of numbered prints. There are no official rules regarding the number of A/Ps created, but in most cases, the numbers are less than 10% of the numbered run. These editions are created and often kept by the artist and print technician as a record of the print’s progression.

p/p: printer’s proof

As the name suggests, a Printer’s Proof is similar to an Artist’s Proof. The Printer’s Proof is an edition produced by the artist and print technician during their creative process perfecting the edition. Like A/Ps, there are only a few P/Ps produced.

t/p: trial proof

Trial Proof prints are pulled while the artist is actively working on the composition, often differing from the regular edition. This is used to assess a print’s progression and may lead to further refinements for the subsequent stages of the work. These trial impressions may not precisely mirror the final edition, and some collectors may appreciate their unique nuances. These prints often feature additional annotations and notes, showcasing the work’s progression.

A question that frequently arises among art collectors is whether the edition number of a print has any significant impact on its value or exclusivity. While some collectors may prefer collecting A/Ps or the number 1 in the print edition, these distinctions do not necessarily enhance the worth or exclusivity of the print. All prints are created by the artist’s hand and are to be enjoyed by everyone at any stage of their art collecting journey!

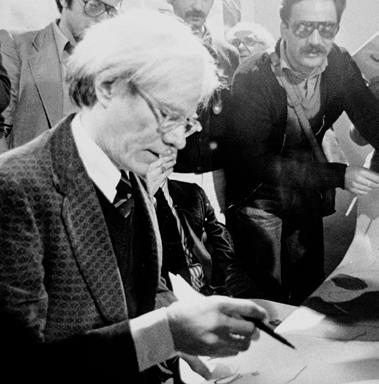

opposite left: Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987) Flowers (Feldman & Schellmann II.6) 1964 offset lithograph, ed. of approximately 300 Sold for $68,750

opposite right: Brent Harris (born 1956) Swamp 1999 etching and aquatint, ed. P/P Sold for $1,875

left: Andy Warhol, 1970 / Alamy right: John Coburn (1925-2006) Garden of Desire 1976 screenprint, ed. A/P Sold for $3,250

favourite artist

How could I choose one? I’m currently writing my thesis on the use of craft in contemporary art, so obviously it would have to be a textile or fibre artist. I have always admired the work of Paul Yore, it’s so bold for a medium traditionally viewed as domestic or hobbyist. I also have to give an honourable mention to the fibre sculpture works of Sheila Hicks (illustrated) and Louise Bourgeois, in all of their colourful and eerie glory.

I love the local walking trails near where I live, so I would definitely start the day with a walk along the beautiful beach from Mordialloc to Black Rock. Then obviously it would have to be followed by a little treat from one of my favourite bakeries, either Bromley’s Bread or Baker Bleu. I also love a good shop at the Prahran Market, so there would be some afternoon cooking involved too. The best way to finish any day is dinner and drinks with friends, if I had to choose a favourite place in Melbourne right now, it would be at Bounty of the Sun.

favourite cocktail

I’m very simple when it comes to my drink order. I don’t like a lot of fuss, so it would absolutely have to be a dry martini with a twist. The best one I’ve had so far in Melbourne was at the Apollo Inn.

what’s on your “saved favourites” list from leonard joel at the moment?

On my first day as the art assistant in the Salon, we consigned an amazing miniature tapestry by the artist Kate Derum, who had a long involvement with the Australian Tapestry Workshop. I’ll always regret not bidding on that work as its consignment felt kismet, so now I’m always keeping an eye out for any contemporary tapestries to add to my favourites!

leonard joel staff all seem to have a side project or talent, what’s yours?

I have an aversion to sitting still, so I always have to have a project in the works. Before studying art, I worked in costume design for the theatre. So apart from helping out with the odd show, I’m always trying to sew/ crochet/tailor things I, or any of my friends or family, might need.

your ideal day in melbournea new amazon original series is captivating worldwide audiences with a real-life look into the shadowy world of elephant poaching, ivory dealers and brokers, and the impact of this criminal activity on the longterm conservation of a species.

The series, titled Poacher, launched on February 23 with eight episodes and subtitles in 35 languages. Poacher brings to light the untold stories behind “Operation Shikar,” a meticulously planned investigation that unfolded between 2015 and 2017. Based on real events, the investigation and arrests targeted suspected elephant poachers, ivory traders, carvers, and high-end ivory art dealers across various regions of India.

“The series captures the essence of actual events and presents it to the world without missing the beauty of the forests of western ghats, the ruthlessness and greed of hardened criminals, and the blood, sweat, and silent hard work of the people who sought to end the hunting,” said Jose Louies, CEO of the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI).

The incidents primarily occurred in Kerala and Tamil Nadu, with connections to the Indian state of Karnataka. The investigation resulted in the recovery of 28 illegal guns suspected to be used in elephant poaching. Operation Shikar won the Prime Minister’s award in 2017 for outstanding protection efforts.

Integral to the success of Operation Shikar was the collaboration between WTI and the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), providing technical and resource support at every stage of the case. The investigation led WTI and IFAW to initiate HAWK, a centralised intelligence management system in Kerala.

Today, HAWK is fully operational, providing real-time information to officials about various wildlife crime-related incidents. As a result, no targeted poaching for ivory has been reported since 2015. Despite these preventive efforts, experts continue to fend against the persistent threat of cunning leaders re-establishing networks.

“It is vital we break down silos in the world of intelligence and security forces that may impede the swift sharing of information, ultimately deconstructing criminal networks and stopping crime before it occurs,” added IFAW President and CEO, Azzedine Downes. “The point is to protect elephants—not to protect the ivory after it’s already too late and the elephants have died.”

Poacher is a powerful narrative that underscores the tireless efforts to combat wildlife crime, showcasing both the triumphs and ongoing challenges in the fight for conservation.

Director Richie Mehta first had the idea for Poacher after noticing the amount of ivory in people’s homes while working on a Google-financed documentary nine years ago called India in a Day. Poacher is available to watch in Australia on Amazon Prime.

On 22 March 2017, the first industry briefing between IFAW (International Fund for Animal Welfare) and auctioneers and antique dealers from Australia took place, with the view to ending the auction and antiques trade in rhinoceros horn and ivory. That same year, Leonard Joel introduced a voluntary cessation policy and we are proud to no longer sell these materials. In the 22nd Report, IFAW share the latest news about their conservation projects.

Art

Jewellery

Luxury

Decorative Arts

Modern Design

+

With astute local market knowledge and extensive global experience, Leonard Joel offers the broadest range of specialist expertise in Australia. Scan the QR code and discover the value of your piece or collection with a complimentary online valuation, book an appointment with one of our specialists, or join us at one of our regular valuation days.

22 June –13 October

YVONNE AUDETTE, CHRISTOPHER BASSI, LYNDA BENGLIS, MIKE BROWN, PUUNI NUNGARRAYI BROWN, MARIO CRISTIANI, ELLEN DAHL, JEFFREY GIBSON, SIMRYN GILL, BRETT GRAHAM, ROCHELLE HALEY, FREDDY MAMANI, RON MUECK, ANNA PARK, LEE SALOMONE, DAVID WALSH & MORE

Imane Ayissi from the Mbeuk Idourrou collection, autumn–winter 2019, Paris, France.

Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Photo © Fabrice Malard, courtesy of Imane Ayissi

Imane Ayissi from the Mbeuk Idourrou collection, autumn–winter 2019, Paris, France.

Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Photo © Fabrice Malard, courtesy of Imane Ayissi

In this feature, we revisit a handful of beautiful and extraordinary pieces that have passed through our doors since the last issue.

I was delighted when contacted by a long-standing client with an important request to assist the family with the sale of their late father’s treasured art collection. Amongst the pieces was Tapestry of Night by John Coburn, acquired in 1966 to coincide with the year of birth of one the children. The painting had remained in the family until only recently.

Coburn, an esteemed Australian artist born in 1925, captivated audiences with his unique blend of abstract expressionism infused with religious and spiritual themes. Over the course of five decades, Coburn dedicated himself to conveying his profound emotions about nature and the world through his art.

Tapestry of Night (1966) immediately captivates the viewer with its vibrant and dynamic use of colour. Coburn employs a rich palette of deep blues, greens, and blacks, evoking the enveloping darkness of the night sky. / Troy McKenzie, Queensland Representative Specialist

John Coburn (1925-2006) Tapestry of Night 1966 Sold for $60,000

Art, March 2024

Josiah Rushton (born 1836) was employed at the Worcester factory until 1871 working as a decorator, specialising in fine figure subjects. He is regarded as the greatest portrait painter from the Worcester factory.

A pair of large Royal Worcester porcelain covered vases

Shape 520, dated 1871–2, the reserves decorated by Josiah Rushton

Sold for $32,500

The Andrew Morris Collection of Important Worcester and Other Porcelain, March 2024

The Italian firm that most successfully profited from the revival of interest in ceramic traditions in the second half of the 19th century, and made the highest quality wares to meet it, was headed by Ulisse Cantagalli (1839-1901).

All of the ingredients that made the Figli di Giuseppe Cantagalli so successful are well represented in this superb tin-glazed earthenware panel by Cantagalli, Florence, circa 1890.

A fine large tin-glazed earthenware panel by Cantagalli Manifattura Figli Di Giuseppe Cantagalli, Florence, circa 1890

Sold for $15,000 Decorative Arts, April 2024

Hermès, exotic Birkin 30, circa 2014

Sold for $45,000 Luxury, April 2024

Charles and Ray Eames lounge chair and ottoman for Herman Miller

Sold for $12,500 Modern Design, April 2024

Rolex Submariner Ref 16613 a stainless steel and gold wrist watch with date and bracelet, circa 1997

Sold for $16,250 Timepieces, March 2024

Hermès, exotic Birkin 30, circa 2014

Sold for $45,000 Luxury, April 2024

Charles and Ray Eames lounge chair and ottoman for Herman Miller

Sold for $12,500 Modern Design, April 2024

Rolex Submariner Ref 16613 a stainless steel and gold wrist watch with date and bracelet, circa 1997

Sold for $16,250 Timepieces, March 2024

With regular auctions in Fine Art, Jewels & Watches, Decorative Arts, Modern Design, Luxury and more, there’s something

to suit every taste at Leonard Joel.

browse

Browse our online auction catalogues or view in person at one of our salerooms.

bid

Create an account online and use it whenever you bid. You can also receive Lot alerts tailored to your interests.

Bidding is simple and you can do so in person, online, by phone or by leaving an absentee bid. Our team is always on hand to guide you.

now delivering

Get your auction purchases delivered straight to your door with Leonard Home Delivery (Melbourne only), our convenient, fast, reliable delivery service managed by our in-house team. Please visit our website for more information or contact delivery@leonardjoel.com.au

connect

Subscribe to our email newsletter through our website to stay up to date with news on upcoming auctions, special events, and industry insights. website leonardjoel.com.au instagram @leonardjoelauctions facebook facebook.com/leonardjoelauctions youtube youtube.com/user/leonardjoel1919

thank you to our leonard magazine partners

The Hughenden Boutique Hotel, Soak Bar + Beauty, Mrs Banks Boutique Hotel

chairman & head of important collections

John Albrecht 03 8825 5619 john.albrecht@leonardjoel.com.au

chief executive officer

Marie McCarthy 03 8825 5603 marie.mccarthy@leonardjoel.com.au

Auction Specialists

important jewels

Hamish Sharma

Head of Department, Sydney 02 9362 9045 hamish.sharma@leonardjoel.com.au

fine jewels & timepieces

Rebecca Sheahan

Head of Department 03 8825 5645 rebecca.sheahan@leonardjoel.com.au

fine art

Wiebke Brix

Head of Department 03 8825 5624 wiebke.brix@leonardjoel.com.au

decorative arts

Chiara Curcio

Head of Department 03 8825 5635 chiara.curcio@leonardjoel.com.au

asian art

Luke Guan Head of Department 0455 891 888 luke.guan@leonardjoel.com.au

modern design

Rebecca Stormont Specialist 03 8825 5637 rebecca.stormont@leonardjoel.com.au

luxury

Indigo Keane Specialist 03 8825 5605 indigo.keane@leonardjoel.com.au

prints & multiples

Hannah Ryan Art Specialist, Manager of Speciality Auctions 03 8825 5666 hannah.ryan@leonardjoel.com.au

sydney

Ronan Sulich Senior Adviser 02 9362 9045 ronan.sulich@leonardjoel.com.au

Madeleine Norton

Head of Decorative Arts & Art, Sydney 02 9362 9045 madeleine.norton@leonardjoel.com.au

brisbane

Troy McKenzie Representative Specialist 0412 997 080 troy.mckenzie@leonardjoel.com.au

adelaide

Anthony Hurl Representative Specialist 0419 838 841 anthony.hurl@leonardjoel.com.au

perth

John Brans Representative Specialist 0412 385 555 john.brans@leonardjoel.com.au

The Auction Salon Specialists

art

Noelle Martin 03 8825 5630 art.manager@leonardjoel.com.au

furniture

April Chandler 03 8825 5640 furniture.manager@leonardjoel.com.au

jewellery

Leila Bakhache 03 8825 5645 jewellery.manager@leonardjoel.com.au

objects & collectables

Dominic Kavanagh 03 8825 5655 objects.manager@leonardjoel.com.au

Valuations

David Parsons

Head of Private Estates and Valuations 03 8825 5638 david.parsons@leonardjoel.com.au

Marketing & Communications

Blanka Nemeth

Senior Marketing Manager 03 8825 5620 blanka.nemeth@leonardjoel.com.au

Maria Rossi

Graphic Artist

Paolo Cappelli Senior Photographer & Videographer

Adam Obradovic

Photographer & Videographer

Sale Rooms

melbourne 2 Oxley Road, Hawthorn, VIC 3122 03 9826 4333

sydney

The Bond, 36–40 Queen Street, Woollahra, NSW 2025 02 9362 9045

Leonard Magazine

editor

Blanka Nemeth

graphic design

Maria Rossi

melbourne 2 Oxley Road, Hawthorn, VIC 3122 03 9826 4333

sydney

The Bond, 36-40 Queen Street, Woollahra, NSW 2025 02 9362 9045

brisbane 54 Vernon Terrace, Teneriffe, QLD 4005 0412 997 080

adelaide 429 Pulteney Street, Adelaide, SA 5000 0419 838 841

perth 0412 385 555

info@leonardjoel.com.au leonardjoel.com.au