3 minute read

AN EXTRAORDINARY STORY

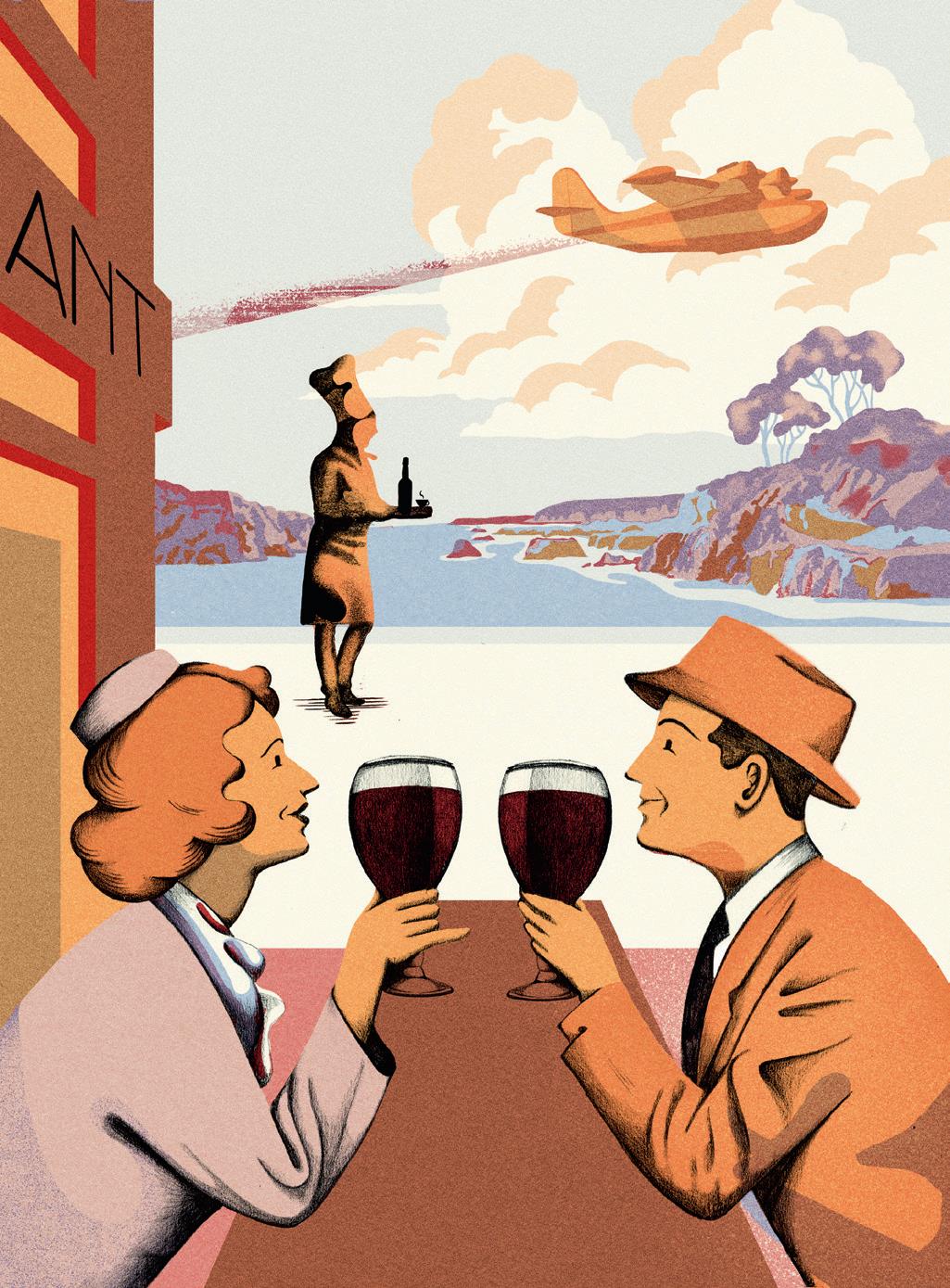

The dayIRISH COFFEE took off

IT WAS DURING WORLD WAR II: IN THE RESTAURANT OF AN AIRPORT BESIDE A SMALL IRISH TOWN, A COOK INVENTED A BEVERAGE TO SOOTHE THE PASSENGERS OF A ROCKY TRANSATLANTIC FLIGHT. IRISH COFFEE WAS BORN.

By Boris Coridian Illustration Icinori

AFTER SIX HOURS OF A CHAOTIC FLIGHT, THE HUGE SEAPLANE TURNED AROUND AND WENT BACK TO FOYNES, ITS TAKE-OFF POINT. The extravagantly proportioned vessel –the obese belly of the cabin utterly incongruous with the modest scale of rest of the plane – prepared to land on the waters of the Shannon Estuary. On this stormy day in October 1943, the frantic whine of the craft’s four engines was almost drowned out by the deafening roar of the rain. The flight, which left the small town on Ireland’s west coast, was carrying its chic passengers across the Atlantic. It was scheduled to arrive in New York after a technical stop in the quiet town of Botwood on the island of Newfoundland, Canada. But they were not to see North America that day. Weary and dazed by their tribulations, the travellers remained firmly on solid ground, after one last boat ride taking them to the seaplane dock. Chilled through, they headed to the airport restaurant, a warm and safe sanctuary. The smell of coffee wafting out of the kitchens quickly invigorated heart and mind. The pleasant dining room was well-known for the quality fare prepared by Chef Joe Sheridan. Though Foynes had no particular sightseeing feature, it had felt the presence of the most eminent personalities in its halls since 1936, when this seaplane airport opened. One had to be a person of means to enjoy transatlantic travel by air, uniting the two continents like never before: one could cross the ocean in a day, whereas a steamer meant a five- or six-day crossing. The guestbook bore signatures of famous figures: John F. Kennedy, Yehudi Menuhin, Eleanor Roosevelt, Ernest Hemingway, Humphrey Bogart, Marilyn Monroe. On that day, however, as World War II raged across Europe, there were no celebrities in Foynes. Only unknowns who, without realising it, would be the first to sample a recipe that would itself travel around the world.

After receiving a Morse code message about the returning travellers, Joe, the cook with the famous toque, quickly concocted a powerful batch of coffee. He then added a dose of Irish whiskey to flavour the hot beverage. Sugar and whipped cream came next, their own form of sweet nourishment. When one passenger regained courage and colour after just a few sips, he asked, “Is this Brazilian coffee?” “No, sir,” Joe replied without thinking, “it’s Irish coffee!” The legend was born. The inventor put the crowning touches on this oeuvre a few days later by knocking on the door of Brendan O’Regan, the establishment’s new, government-appointed manager, who was charged with making the place a showcase of Irish lifestyle. When the chef suggested serving his new recipe in a clear glass, O’Regan quickly grasped that this might mean the birth of a potential national emblem. The chef described the recipe: “After warming a glass with hot water, pour in a teaspoon of brown sugar and a generous shot of Irish whiskey. Then fill it up with good, strong coffee to within a centimetre of the rim. Next, using the back of a spoon, carefully add lightly whipped cream to the brim. Do not mix, by any means! Sip by drinking the coffee through the cream.” With the deep black liquid, creamy white foam, and warm, delicious smell, it was – and is – the perfect coffee cocktail. Its reputation crossed the world’s oceans and found a new home in San Francisco. In 1952, Joe Sheridan was invited to work at Buena Vista Café, where he would continue preparing his signature beverage until his death in 1962. But a legend never dies: his Irish coffee still revives chilled and weary souls. It even embodies the soul of its people: “Cream as rich as an Irish brogue, coffee as strong as a friendly hand, sugar as sweet as the tongue of a rogue, and whiskey as smooth as the wit of the land.” So, as the locals say in Gaelic in the pubs, sláinte! n