TERRITORIO COMPARTIDO

Casapoli Residencias | Ciclo 2016

Pág 01

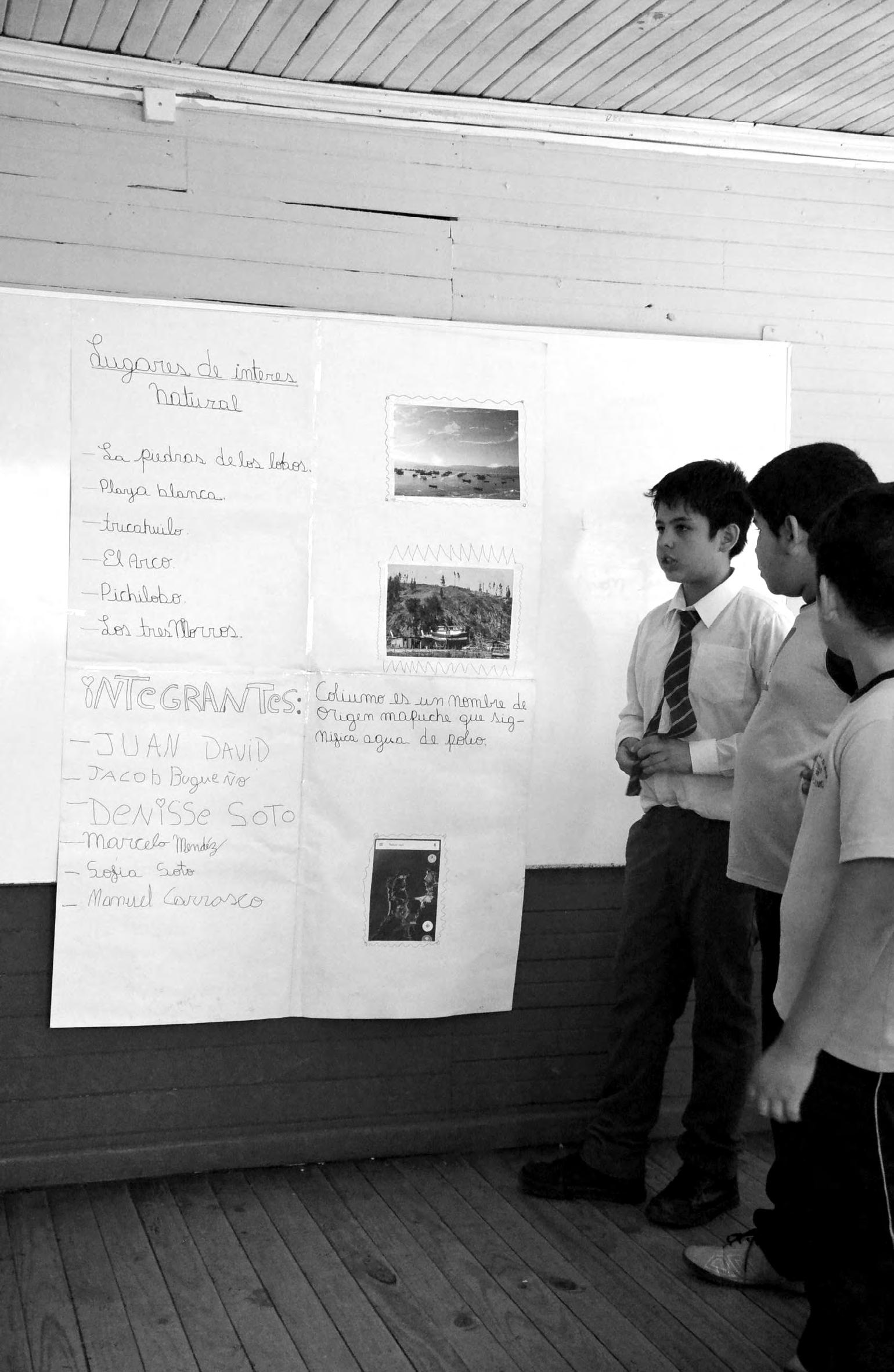

Texto escrito por alumnos de la Escuela Vegas de Coliumo en el desa rrollo de taller sobre residencias. Registro Daniel Cartes. Pág 03

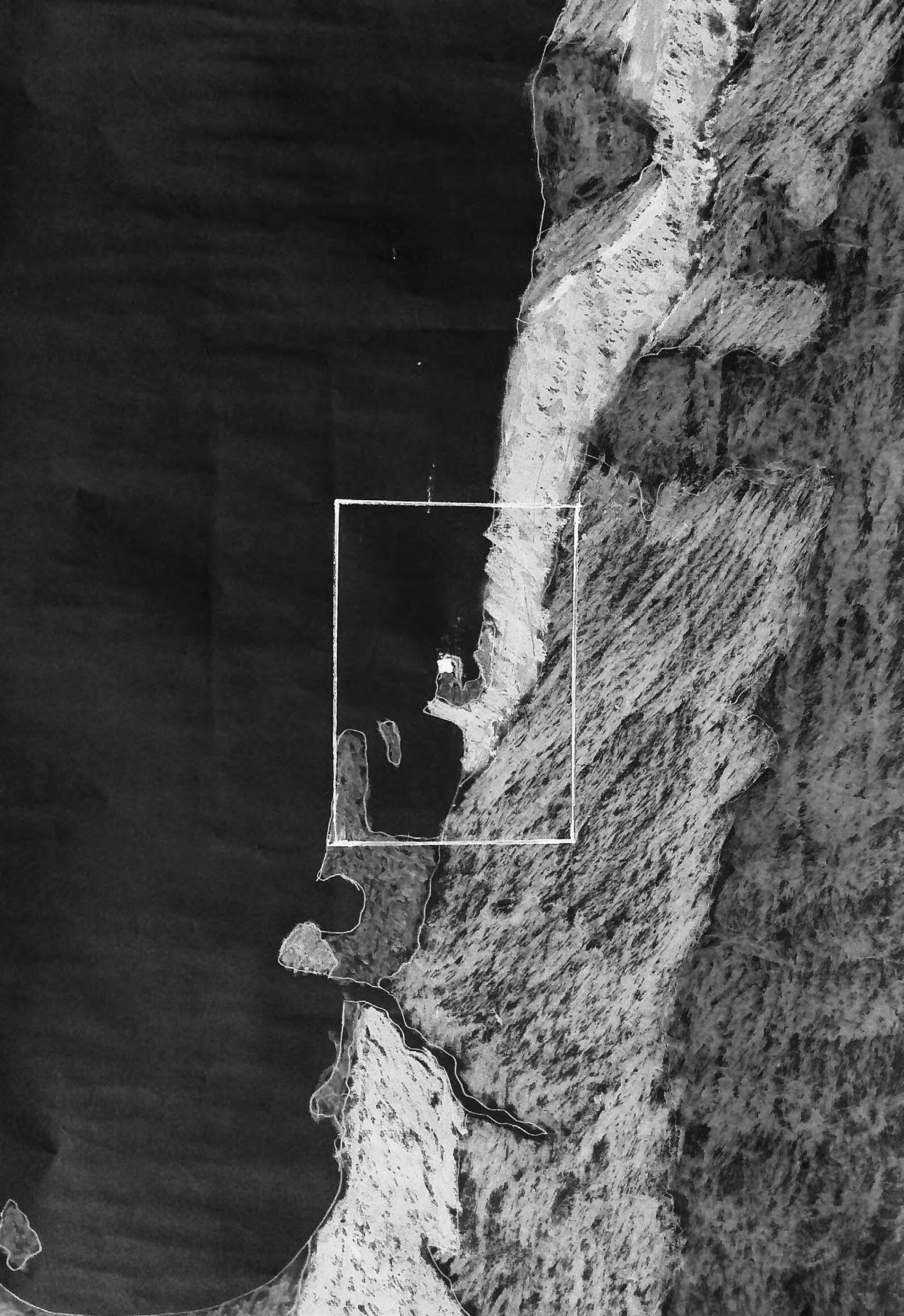

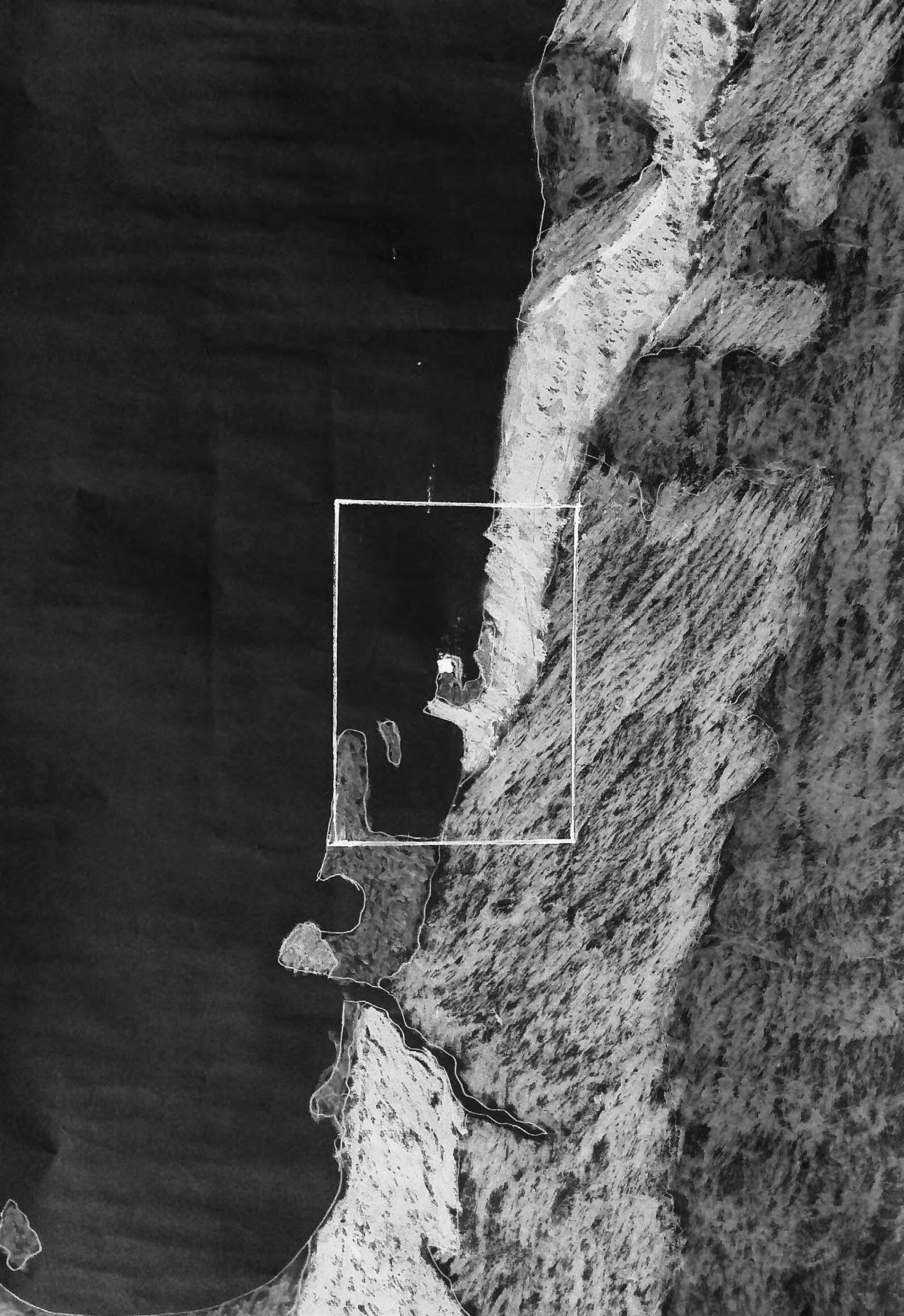

Vista aérea de Coliumo. Registro Oscar Concha.

TERRITORIO COMPARTIDO

Casapoli Residencias | Ciclo 2016

INDICE

Leslie Fernández + Oscar Concha

David Romero

Francisco Navarrete Sitja + Osvaldo Ulloa

Eduardo Cruces + Andrés Tassara

Gonzalo Cueto + Alvaro Espinoza

Alejandro Quiroga + Javier Ramírez

Natascha de Cortillas + Noelia Carrasco

Daniel Cartes

Pablo Rivera

Carla Motto

Victoria McReynolds Xavier Tavera

Francisca Sánchez

Patricio Vogel Sebastián Jatz

Traducción

Exploración de campo, Coliumo

Apropiaciones y lecturas desde el paisaje de Coliumo Territorios compartidos, o en la búsqueda de nuevos territorios por explorar Estallar la línea; diluir la tierra In-situ-ando

Ese mar que tranquilo nos baña Paisaje, territorio y comunidad La culinaria de Coliumo como hecho social total Espacio educativo | espacio político

La piedra ideal Calar - recorrer La última batalla entre la forma y la luz Retratos

01234 O breve descripción secuencial hacia los dibujos materiales La fascinación del olvido Arpas eólicas Traducción Políptico desplegable

08 12 16 24 32 38 42 50 58 62 66 70 76 80 84 89

APROPIACIONES Y LECTURAS DESDE EL PAISAJE DE COLIUMO

Leslie Fernández | Oscar Concha | Directores Casapoli Residencias

Desde su construcción y funcionamiento, hace ya 12 años, Casapoli se ha transformado en un espacio referencial para las artes visuales contemporáneas en Chile, siendo sede y locación para el desarrollo de diversas actividades vinculadas a la producción artística, permitiendo una ampliación gradual de vínculos en el ámbito nacional e internacional.

A partir del programa de residencias, una de sus principales actividades, han circulado por Coliumo y por Concepción artistas provenientes de diferentes lugares de Chile y del extranjero, lo que para una región lejana del centro político y administrativo de Chile, si no en la periferia, no es algo que suceda de manera habitual.

Parte de nuestra inquietud, como directores del programa de residencias desde el 2010, ha significado ir reforzando la conexión con la localidad de Coliumo por medio de los vínculos establecidos durante este tiempo con personas clave, nos referimos específicamente a Nelson Gutiérrez, profesor de la Escuela Vegas de Coliumo, y Ricardo Villagra, pescador y propietario de la cocinería El Loro, quienes, desde su respectivos lugares, han entregado un apoyo fundamental para los proyectos realizados por nuestros residentes. Pero además hemos ido ampliando una relación con artistas que viven en Tomé, Concepción y con la Universi dad de Concepción, a través de docentes y alumnos del Departamento de Artes Plásticas, sumándolos a las actividades surgidas desde Casapoli.

Entendemos la producción artística desarrollada desde las residencias como la posibilidad de asumir una ubicación geográfica, un paisaje que puede ser abordado desde lo cultural, político o social descartando la figura que instala a un artista en un espacio, solo para el retiro o la introspección, como si se tratara de un contexto cualquiera.

A partir de la profundización de las reflexiones en torno al territorio, producto de la continuidad de este proyecto bajo nuestra dirección, el segundo semestre de 2016 desarrollamos un ciclo llamado Territorio Compartido , ciclo de residencias para artistas visuales e investigadores, a través del cual se buscaba generar un trabajo interdisciplinar entre duplas constituidas por investigadores de las Ciencias y las Artes Visua les. Es así como invitamos a profesionales del área de la Oceanografía, Geología, Biología Marina, Historia del Arte y Antropología para que, durante dos semanas, convivieran con artistas visuales para compartir miradas desde cada disciplina en relación con situaciones problemáticas que constituyen el contexto. En total fueron 5 residencias realizadas en parejas, determinadas previamente por afinidades y temáticas que constituyen la especialidad de ambos investigadores, haciendo especial énfasis en la generación de inter cambios entre los procesos de cada uno. Las duplas, ordenadas temporalmente, estuvieron constituidas por Francisco Navarrete Sitja y Osvaldo Ulloa, Eduardo Cruces y Andrés Tassara, Gonzalo Cueto y Álvaro Espinoza, Alejandro Quiroga y Javier Ramírez y por último Natascha de Cortillas y Noelia Carrasco.

Una parte importante para este proyecto fue, sin duda, la sociabilización de estas experiencias, realizadas en diferentes Departamentos y Facultades de la Universidad de Concepción, en donde los investigadores de las ciencias ejercen labores docentes. A pesar de ser un proyecto que surge desde las Artes visuales, esta acción significó un desplazamiento hacia los centros operativos de las otras disciplinas, lo que también contribuyó a ampliar el público que habitualmente participa de charlas y conversatorios convocados desde el arte.

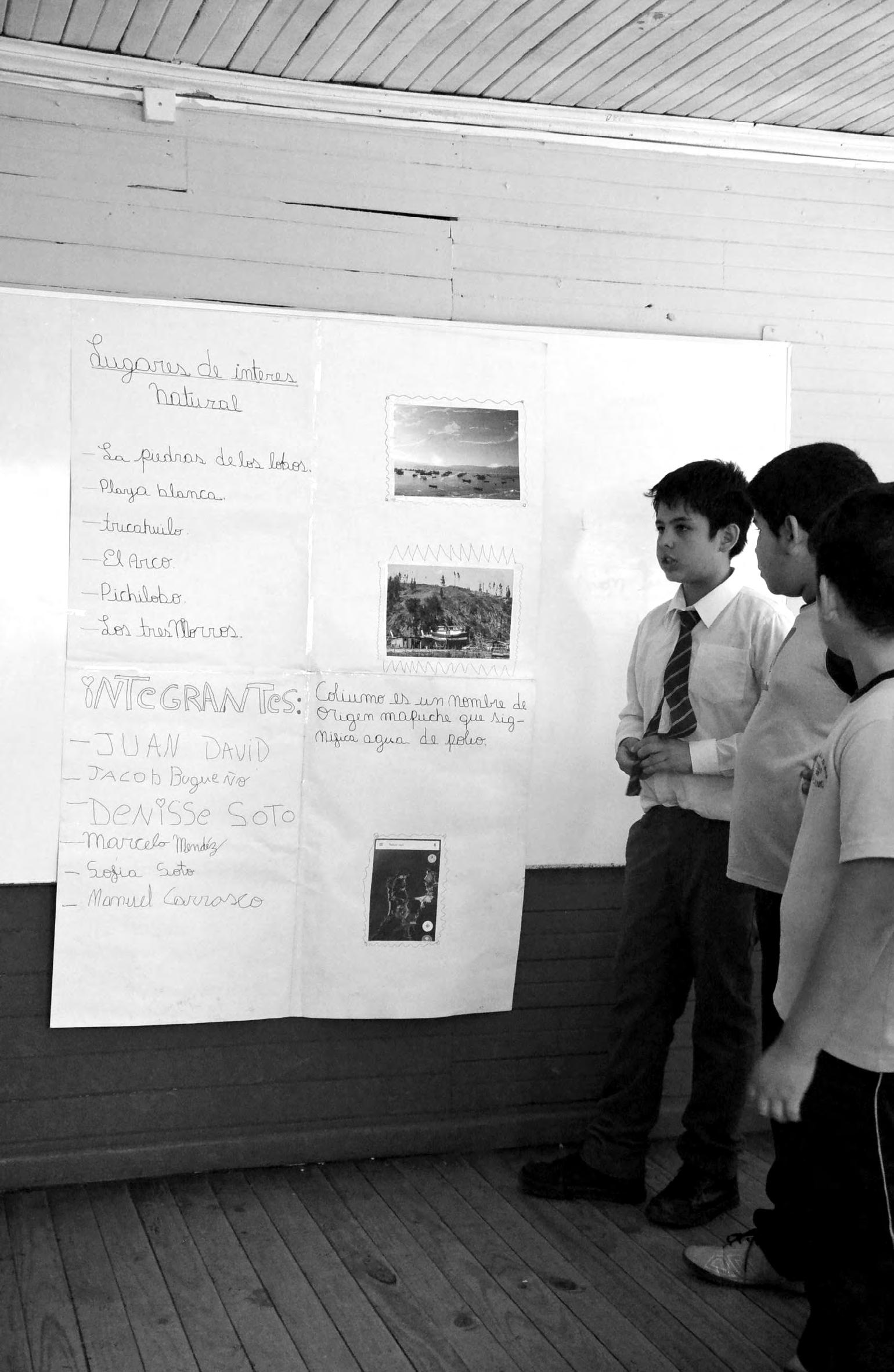

Quisimos cerrar este ciclo con un taller realizado en la Escuela Vegas de Coliumo, que estuvo a cargo del li cenciado en arte Daniel Cartes. El taller consistió en trabajar con niños de quinto básico a octavo básico y sus profesores, donde se pusieron en práctica diferentes didácticas que abordaron las metodologías y temáticas utilizadas por los artistas e investigadores de Territorio compartido.

Aparte de la realización de ese ciclo, el 2016 fue un año especialmente activo para Casapoli. A comienzos de año, los artistas Pablo Rivera y Carla Motto (ambos de Santiago) desarrollaron respectivamente sus proyectos que contemplaron estudios de campo y exploraciones en el contexto. En el mes de julio, dos artistas extran jeros, el fotógrafo Xavier Tavera (Minnesota) y la arquitecto Victoria McReynolds (California) desarrollaron sus investigaciones individuales simultáneamente y producto de la convivencia confluyó además en un traba jo colectivo. Por último, a partir del programa Traslado, una convocatoria nacional realizada por el Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y las Artes, fueron seleccionados los proyectos de Francisca Sánchez, Sebastián Jatz, Patricio Vogel, los 3 de Santiago.

Cada uno, a partir de prácticas muy distintas, abordó el paisaje, la comunidad y el territorio. La experiencia de haber convivido, aun en un tiempo breve, con investigadores y artistas, conociendo diferentes procesos de trabajo, ha permitido además ir ampliando las relaciones más allá del plano profesional, integrando la afecti vidad manifestada desde los vínculos mantenidos luego del termino de cada residencia. Las infinitas lecturas por medio de las cuales es posible abordar un mismo territorio, nos permiten entender estas relaciones como una figura orgánica, que se va adaptando a lo que acontece en cada tiempo.

Hemos procurado, a partir de la permanencia en la dirección del proyecto de residencias de Casapoli, asumir estar situados en la Caleta Coliumo, Tomé, Octava Región de Chile, como un contexto particular con carac terísticas que se desprenden de su condición geográfica costera, centrada principalmente en el desarrollo de actividades vinculadas a la pesca, la recolección de algas y secundariamente a la actividad agrícola. Un territorio situado a mar abierto, que nos mantiene simbólicamente conectados con el mundo, pero al mismo tiempo nos lleva a convivir con una realidad local.

08

09

Francisco Navarrete Sitja + Osvaldo Ulloa

Eduardo Cruces + Andrés Tassara

Gonzalo Cueto + Alvaro Espinoza

Alejandro Quiroga + Javier Ramírez

Natascha de Cortillas + Noelia Carrasco

15 al 30 de agosto 01 al 15 de septiembre 16 al 30 de septiembre 01 al 15 de octubre 16 al 30 de octubre

TERRITORIOS

COMPARTIDOS, O EN LA BÚSQUEDA DE NUEVOS TERRITORIOS POR EXPLORAR

David Romero | Investigador y Artista Visual

Al comenzar este texto debo sincerar la posición desde la cual escribo. Me encuentro residiendo hace más de un año en Suiza, a una considerable distancia geográfica y temporal respecto de los hechos ocurridos durante el ciclo de residencias Territorio Compartido de Casapoli, en Coliumo.

Por lo tanto, mi reflexión no está basada en la observación directa y presencial de los acontecimientos, sino en la experiencia transmitida a través de diversos textos, registros y diagramas, es decir, a través de trazos que testimonian, ante todo, el desarrollo de procesos signados por el diálogo y la colaboración interdisciplinar.

Es importante puntualizar lo anterior, en tanto uno de los objetivos del proyecto Territorio Compartido ha sido precisamente dislocar las barreras que impone la distancia, no sólo geográfica y temporal, sino, aún más relevante, aquella que se impone entre el arte y otras formas de producción de conocimiento. Esta distancia, que separa y segmenta las formas del conocimiento, ha sido, efectivamente, impuesta por un modelo fun damentado en la distribución jerárquica de roles y funciones que, por ejemplo, separa el saber artístico del saber científico. Bajo ese modelo, lo que se espera del arte es que produzca obras, y que esas obras transmitan una experiencia circunscrita a los códigos e instituciones propios del sistema artístico. Este es el territorio convencional del arte, algo que representa una trinchera demasiado acotada para la noción de territorio que aquí se buscó explorar.

El título de este ciclo de residencias, Territorio Compartido, contiene implícita la idea de explorar nuevas te rritorialidades. Compartir un territorio indica la búsqueda de lo común allí donde artificiosamente tiende a imponerse la separación; plantea el desafío de construir puentes que conecten a la práctica artística con nuevos territorios, desde la geografía y el paisaje que rodean a Casapoli hasta los territorios representados por otros saberes y disciplinas. De este modo, con la idea de expandir las territorialidades de la práctica artística, se propuso poner en diálogo a artistas y trabajadores del ámbito de las ciencias.

Francisco Navarrete Sitja trabajó junto al oceanógrafo Osvaldo Ulloa; Eduardo Cruces, con el geólogo Andrés Tassara; Gonzalo Cueto junto al biólogo marino Álvaro Espinoza; Alejandro Quiroga dialogó con el historiador de arte Javier Ramírez, por último, Natascha de Cortillas trabajó junto a la antropóloga Noelia Carrasco.

Todos ellos desarrollaron metodologías de trabajo que van a contramano de la segmentación de los saberes, indagando en los procesos comunes de lo interdisciplinar, allí donde la diferencia ya no es un impedimento sino un aspecto enriquecedor de la práctica y la reflexión en conjunto. Aquí, la ciencia no es planteada como un “tema” del arte, sino que arte y ciencia son concebidos como esferas que desarrollan metodologías de in vestigación y formas de conocimiento que, en colaboración mutua, permiten expandir el pensamiento crítico respecto de lo que nos rodea. En este caso, en torno a problemáticas situadas en un contexto específico: la península de Coliumo y sus alrededores.

Volviendo a la relación específica entre el arte y la ciencia, esta última ha dado nuevas herramientas a las prácticas artísticas contemporáneas: conocimiento e innovaciones técnicas que han jugado un rol importante en el desarrollo del arte reciente. Pero más aún, podemos decir que si el arte es una experiencia humana que aborda diferentes aspectos de nuestra existencia en el mundo, y la ciencia es una experiencia humana que busca generar conocimiento sobre nuestra existencia en el mundo, entonces la relación entre arte y ciencia es intrínseca, aun cuando pueda llegar a ser una relación problemática.

Este diálogo es posible porque el arte se basa en dos esferas que al mismo tiempo son inseparables y con tradictorias: lo sensible y lo intelectual. Esta condición es la que, precisamente, configura el conocimiento proporcionado por la experiencia artística. Por otro lado, la ciencia no es neutral, no lo es ni en sus metas ni en sus resultados, y siempre está involucrada en dilemas éticos y políticos. Este es uno de los aspectos fundamen tales de la relación entre arte y ciencia, en tanto dicha relación abre la puerta a cuestionamientos que toman a lo sensible como elemento fundamental del pensamiento. Usualmente se dice que la ciencia es una disciplina de la cual se espera algo útil o que cumpla una función específica, descartando el aspecto de lo sensible en su proceder, pues bien, desmitificar las representaciones del artista y el científico ha sido uno de los objetivos de las residencias organizadas en este ciclo de Casapoli.

Ahora bien, acaso el aspecto más relevante de este diálogo interdisciplinar ha sido poner en valor los procesos metodológicos que aproximan a la producción artística y científica. Es aquí en donde emerge la importancia dada a la investigación en su cualidad de trabajo en sí mismo, es decir, la investigación concebida más allá de los ‘productos’ o ‘resultados’ que habitualmente se demandan de ella. Así, entonces, la característica común que conecta a las duplas de cada una de las residencias es la siguiente: su condición de investigadores o investigadoras.

INVESTIGACIÓN

Cuando hablamos de la investigación como un aspecto fundamental de la práctica artística ¿qué significa esto? ¿Cuáles son los énfasis, las potencialidades? Uno diría que la práctica artística, en tanto proceso investi gativo, abre precisamente la posibilidad de dialogar con otras disciplinas y saberes que tienen a la investiga ción como su rasgo constitutivo; así también, permite establecer una relación más estrecha con el contexto en tanto la experimentación no se reduce a fenómenos puramente formales sino que se conecta con situaciones en el plano de lo político, lo social y lo cultural, algo que se aprecia nítidamente en el trabajo desarrollado en estas residencias.

Lo cierto es que la práctica artística desarrollada como herramienta de investigación no es ni mucho menos

12

13

algo reciente, se manifiesta ya en las primeras décadas del siglo XX con las prácticas de arte de vanguardia en la Unión Soviética pos-revolucionaria, creando complejos procedimientos de investigación en el cine y en la literatura. De acuerdo con Hito Steyerl, “la variedad de enfoques estéticos desarrollados como herramientas de investigación hace casi cien años es pasmosa”, y ha estado ligada desde un inicio al pensamiento político y a las luchas emancipadoras a lo largo del siglo XX:

Muchos de los métodos históricos de investigación artística estén ligados a movimientos sociales o revolucionarios o a momentos de crisis y reforma. Dentro de esta perspectiva, se revela el contorno de una red global de luchas, que abarca casi todo el siglo XX y que es transversal, relacional y (en muchos casos, aunque ni mucho menos en todos ellos) emancipadora.1

Se trata, en definitiva, de algo muy simple: cuestionar el régimen de lo dado - saberes, representaciones, po deres -, descifrar sus lógicas de poder, iluminando así un tipo de reflexión cruzada por el aspecto sensible. Ello significa subvertir las jerarquías que habitualmente determinan la aprehensión del sentido artístico. Cuando toman la palabra otros actores, habitualmente privados de palabra, y las categorías que amarran la unidad del sentido se ponen así en evidencia, estamos en presencia de un espacio de disenso, fundamento de la subjetivación política.

Ante todo, investigar significa poner a prueba las certidumbres y exponer(se) a la contingencia. La investiga ción es dialógica en tanto necesita ir al encuentro de otros que están produciendo conocimiento para contras tar teorías y procesos. La investigación también involucra un compromiso con aquello que es su objeto, ¿cual sería el objeto de investigación del arte? o más específicamente ¿cuáles son los objetos de investigación que se vislumbran en el ciclo de residencias de Casapoli?

En verdad, más allá de objetos particulares de investigación, lo que podemos observar es la articulación de diferentes conceptos que son producto de la experiencia con el entorno natural que rodea a Casapoli y la realidad social que lo intersecta. Palabras tales como borde, imaginario, fractura, memoria, lo visible, lo intan gible, el porvenir, adquirieron el rango de ejes conceptuales que movilizaron las operaciones y metodologías de los investigadores.

Es necesario agregar que la relación con la naturaleza, en Chile, está dominada por dos polaridades: ignoran cia y explotación. Romper con ese modelo pasa necesariamente por afianzar nuevas relaciones entre distintos campos de conocimiento.

CONOCIMIENTO

En Territorio Compartido se ha puesto en valor el carácter performativo del conocimiento, como una construc ción que deriva y se transforma de acuerdo con una red de múltiples conexiones. Esto va de la mano con una noción expandida de territorio, dentro del cual se configuran procesos, conceptos y formas de hacer. Bajo esta concepción, el arte es una manera de obtener y transmitir saberes, y no sólo de producir cosas u objetos, es decir, se identifica con una “libertad de conexiones” (Luis Camnitzer) para organizar y expandir el conocimiento.

En esta concepción del arte, donde la investigación es un aspecto esencial de ella, lo que importa no es la obra como objeto final del proceso, sino el proceso mismo como un encadenamiento de distintos momentos de visibilización y/o socialización:

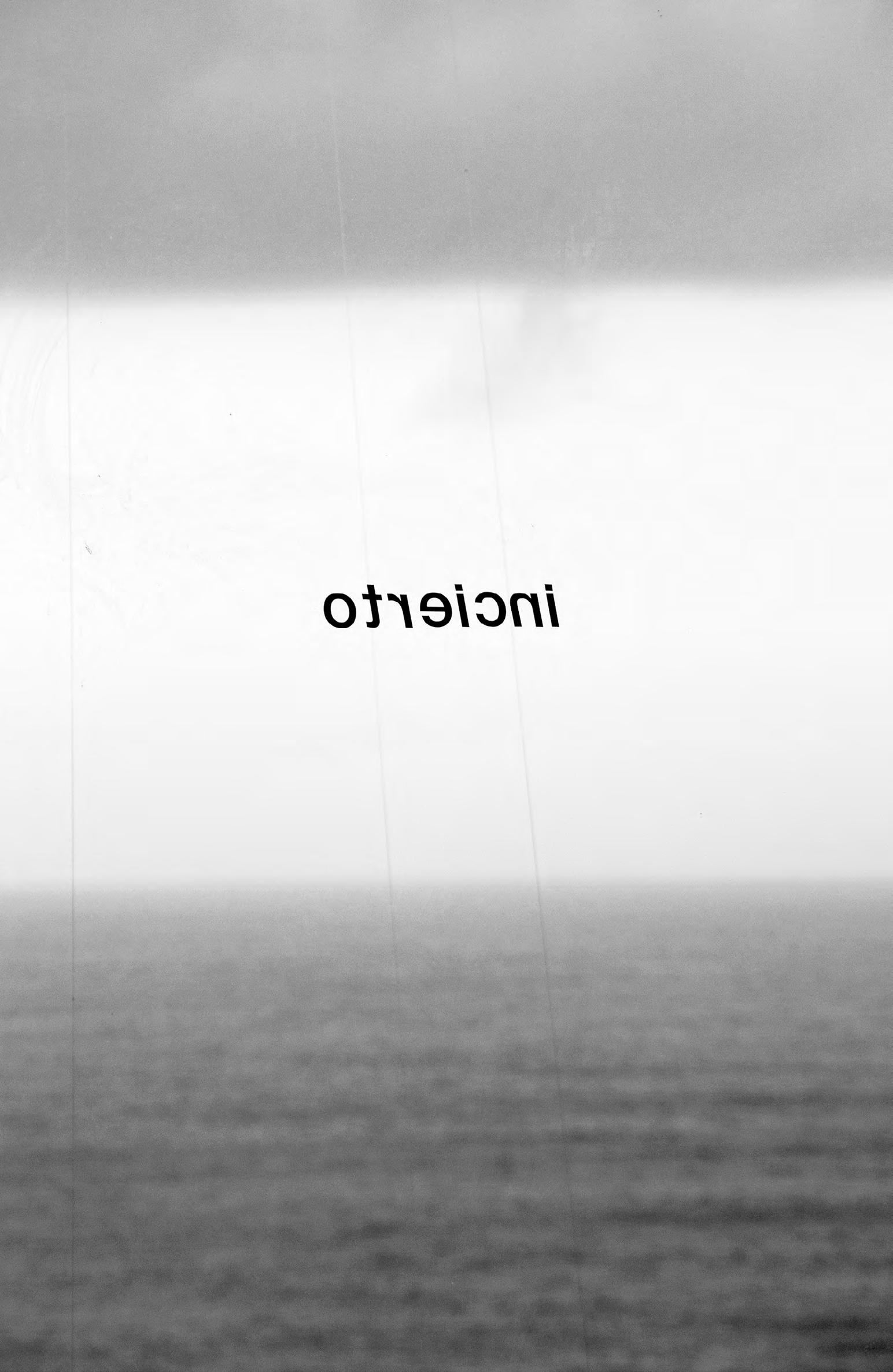

La “incertidumbre” propia de un trabajo desarrollado de ese modo, demanda una especial atención a los momen tos de sociabilización y/o exhibición, puesto que éstos evidentemente ya no otorgan una importancia exclusiva a la disposición objetual, a la obra encerrada en sí misma. 2

Este es otro aspecto que destacar de Territorio Compartido, lo cual fue concretado a través de los distintos conversatorios que se realizaron luego de finalizada cada una de las residencias. Esta actividad tuvo lugar en los departamentos académicos de los investigadores de la Universidad de Concepción: la Facultad de Quí mica, la Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Oceanográficas y el Departamento de Antropología. Ello permitió comunicar los procesos de trabajo a un público diverso, enfatizando el diálogo interdisciplinar y generando un momento de intercambio entre el espacio académico y las prácticas situadas en el territorio.

Esto es importante porque vuelve a plantear la pregunta respecto del rol de la universidad como espacio de producción de conocimiento y la necesidad de una apertura hacia lo que ocurre en sus extramuros. Hablo de la función social y cultural de la universidad en relación con la esfera pública, algo que por largo tiempo ha sido denegado en favor de intereses privados y económicos. Hay toda una institucionalidad consagrada a la división y privatización del conocimiento; la universidad, en nuestro país, es parte de aquel sistema. En este sentido, abrir una brecha y explorar nuevos diálogos disciplinares dentro del espacio académico representa al mismo tiempo una forma de crítica institucional y un deseo de instituir un nuevo de tipo de relaciones extra-académicas.

Además, este deseo de extender la experiencia artística interdisciplinar hacia otros públicos o audiencias, plantea la pregunta en torno a cuáles serían las estrategias pedagógicas adecuadas para la transmisión de conocimientos basados en procesos de investigación como los que se desarrollaron en Territorio Compartido. Un tipo de pedagogía que explore las distintas formas de ver, asimilar y posicionarse frente a un determinado fenómeno, y que no esté basado en el discurso autoritario de quien posee un saber para ser aprehendido por quien no sabe.

Así puede entenderse la iniciativa de mediación que Territorio Compartido encomendó realizar al artista y pedagogo Daniel Cartes en la Escuela Vegas de Coliumo.

Para finalizar, quisiera destacar el que varios de los investigadores que participaron en este ciclo de residen cias plantearon el propósito de darle continuidad a los procesos de trabajo iniciados en Territorio Compartido. Nada se da por cerrado, entonces, por el contrario, este proyecto representa el inicio de procesos y metodolo gías que quedan abiertos a futuras etapas de trabajo.

La incertidumbre en torno a una probable “obra” que diera por concluido los procesos se transformó en valor en sí mismo, en otras palabras, si pudiéramos describir el ‘resultado’ de Territorio Compartido este ha sido, ante todo, el “concebir subjetividades, sin la inminente urgencia de la producción”. 3

1 Hito Steyerl, ¿Una estética de la resistencia? La investigación artística como disciplina y conflicto. En internet: http://eipcp.net/ transversal/0311/steyerl/es

2 Cristián Muñoz y David Romero, La puesta a prueba de lo común. Una aproximación a los discontinuos trazos de la dimensión colectiva en el arte contemporáneo penquista, pág. 34.

3 Palabras de Francisco Navarrete Sitja, durante la presentación de su proceso de trabajo en Territorio Compartido junto a Osvaldo Ulloa, en la Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Oceanográficas de la Universidad de Concepción.

14

15

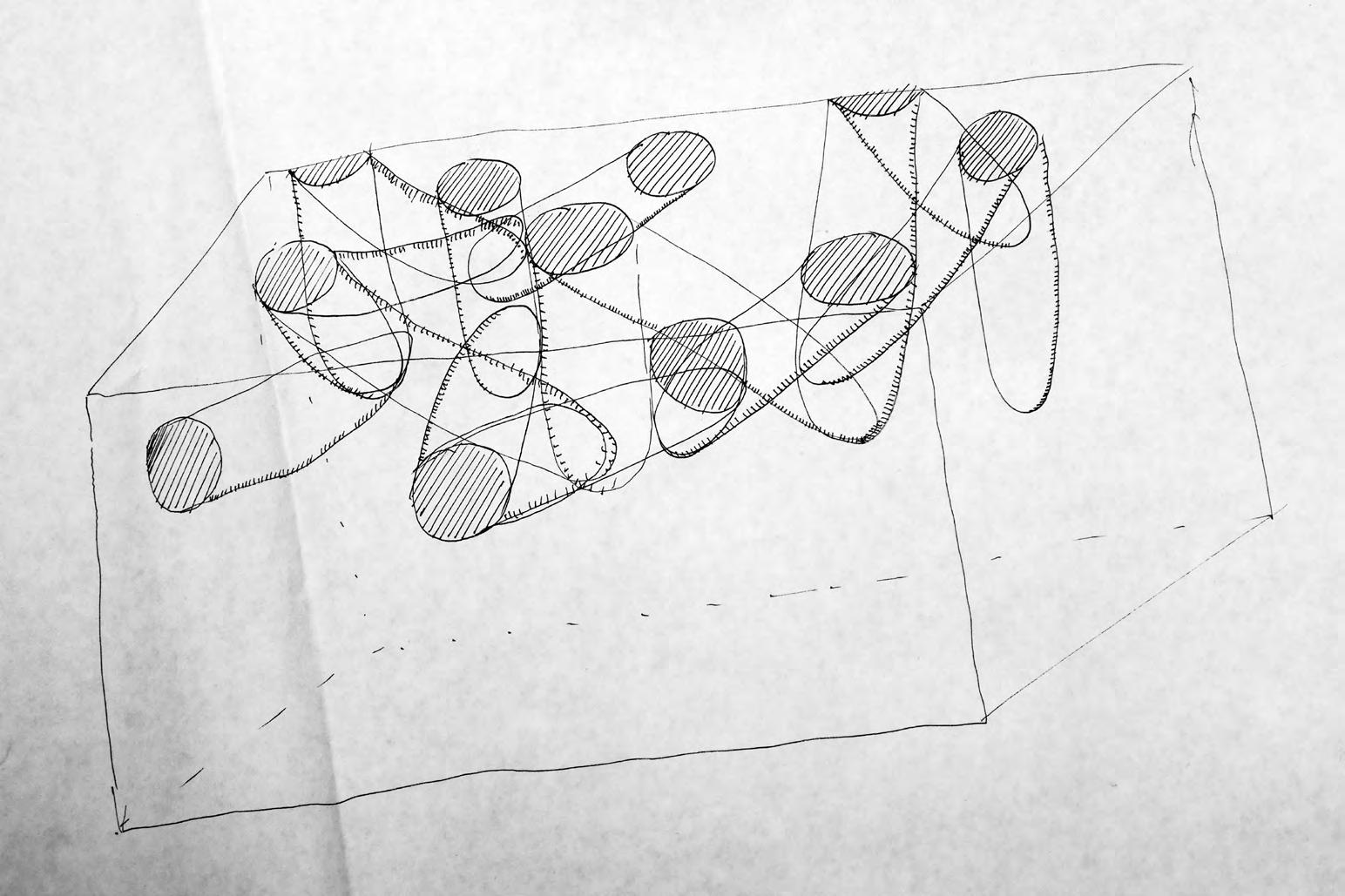

ESTALLAR LA LÍNEA; DILUIR LA TIERRA

Francisco Navarrete Sitja | Artista Visual Osvaldo Ulloa | Oceanógrafo

Mi acercamiento al océano fue desde la orilla. No pude ingresar, no pude embarcarme ni ver sus pro fundidades. Aparte de encontrar un certificado que alude al nacimiento y migración de mi bisabuelo desde un pueblo costero de Cataluña (España) en 1890, y la experiencia de un pasar frente al Terminal Pesquero Metropolitano, no he encontrado más da tos en mi historia que guarden relación con el mar. Nací y viví 28 años en la capital de Chile, donde no se habla del océano más que por noticias regionales, diversión, glorias navales u oferta turística. Para San tiago el mar no existe.

Desconozco las artes de pesca, oficios y la realidad del pescador artesanal, de los armadores, tripulan tes, mariscadores y recolectores de orilla. Tampoco fui seguidor de la representación de la “caleta” en manos de la parrilla televisiva nacional; programa ción que por décadas ha estado al servicio de ho mologar y aniquilar la diversidad cultural de nuestra geografía. De ahí que, en el contexto de esta expe riencia de residencia, diálogo crítico e interdiscipli nar, surge mi intención de tomar ese “vacío” como un espacio donde concebir subjetividades en torno al océano sin la inminente urgencia de la producción.

En este sentido, quizás debido a ciertas operaciones y derivas presentes en mis últimos proyectos reali zados en locaciones específicas, tomé este “residir” como una instancia para experimentar el entorno inmediato de Punta de Talca, especular sobre el mar e interpelar a mi compañero Osvaldo Ulloa, Ocea nógrafo de la Universidad de Concepción. En un principio, esta interpelación estuvo enfocada en dia logar sobre la percepción, metodologías y medios de representación empleados por la ciencia para la

producción de modelos predictivos y comprensión de fenómenos que no podemos percibir. Esto, a partir de su especialidad en oceanografía biológica, interacciones y adaptación de microorganismos a ambientes carentes de oxígeno, de extrema acidez y profundidad.

Las preguntas dirigidas a mi compañero abordaron asuntos de índole epistemológico con la intención de explorar posibles filiaciones a partir de cuestio nes formales y conceptuales; enlaces e ideas que derivaron en puntos de encuentro y desencuentro entre nuestras aproximaciones al océano y prácticas mediales a partir del registro, codificación, archivo y representación de determinados entornos median te imagen y sonido. Igualmente, hablamos sobre la organicidad de la práctica artística y racionalidad atribuida a la ciencia, y dialogamos particularmente sobre las nociones de inspiración, verdad, reciproci dad, predicción e intuición. También conversamos sobre el lugar del “azar” y el “error” en la investiga ción, y discutimos sobre la relevancia de la emotivi dad en los sistemas de producción de conocimiento y cómo éstos podrían generar relaciones afectivas y subjetivas más sustentables.

Así, a través de un diálogo en ocasiones fluido o fa llido, ideé algunas reflexiones y conexiones a partir de mi interés por la representación del territorio, reinterpretación de narrativas asociadas al paisaje y configuración de la mirada. En estas ideas destaca mi intensión de gestar diálogos entre la condición superviviente de las imágenes –juego de intermi tencias, montajes, aparición, desaparición y ciertos relatos locales, sobre supervivencia, que se podrían enlazar, subjetivamente, con investigaciones sobre

16

organismos que sobreviven en zonas oceánicas que carecen de oxígeno en nuestra costa; o el en friamiento de las masas de agua que circulan frente al país en tanto acontecimiento premonitorio para el futuro del planeta, entre muchos otros. Temas y derivas simbólicas que, en un futuro, me permitirían enlazar problemáticas globales y locales, abordar la memoria como suceso especulativo e interpelar la dinámica del espacio geográfico y dispositivos digi tales de representación y circulación de imágenes.

Por otro lado, creo importante mencionar algunas tensiones en nuestro diálogo. Esto, entendiendo que Osvaldo Ulloa, mi compañero de residencia, no sólo realiza investigación, si no que presta asesoría científica en el ámbito gubernamental, y participa además en una pequeña agrupación cultural en la localidad rural de Coliumo. Así, apreciando estas ca pas de acción, me pareció pertinente desmontar el prejuicio de que las prácticas artísticas deben estar orientadas a conmover; persistiendo así en el valor del entramado de reflexiones–materiales y concep tuales–, acciones, operaciones y conocimientos sen sibles que desde la intromisión del arte posibilitan otros saberes y sensibilidades.

Asimismo, respecto de la necesidad de transmisión de conocimiento de la ciencia, me pareció necesa rio debatir la idea de que la práctica artística puede ingresar a la ciencia y comunidad como medio para ilustrar investigaciones científicas; afirmación que se sustenta en que el arte permite “bajar” contenidos a “la gente”. Lo mismo respecto de la idea de que el “valor intrínseco” de un elemento adquiere “sig nificado” al ingresar en el relato hegemónico de la historia y patrimonio nacional. Para mí, la práctica artística debe hacer todo lo contrario, desmontar ese relato de poder. Es sabida la peligrosidad de ese juego, más aún en el contexto de la instrumentaliza ción de la cultura, comercialización de lo simbólico e industria del turismo global. Si “predecir” permite “modificar conductas” y la investigación científica es “modulada” por la libre “demanda”, no debemos perder de vista como los modos de producción del conocimiento–al amparo del neoliberalismo– han sido orientados para propiciar un mercado basado

en la producción de imágenes genéricas y prolifera ción de escenarios a partir de modelos predictivos y nuevos oráculos simbólicos.

Por último, volviendo a esta experiencia, me pare ce importante destacar que durante la residencia no interactué con la comunidad, ya que decidí que eso sería posterior a mis caminatas y diálogo con mi compañero. Luego se acabó el tiempo y esa inquie tud se transformó en idea fuerza para volver y salir a su encuentro. Sería entonces un re-situarme en la orilla, pero de forma distinta, con otras visiones, para recolectar signos, precisar lenguajes, conexiones y replegarme en la dimensión social y psicológica del contexto; esa dimensión que la disponibilidad, idea lización de la representación del entorno natural y narrativa patriótica han dañado y dejado desprovis ta de imagen. Entonces, lo que sigue es salir al en cuentro de ese otro paisaje, uno de capas vulnera bles, erráticas, subalternas, intermitentes, nómadas y en fuga. Imaginando quizá que la migración tran satlántica de un albañil–mi bisabuelo– podría ser, de algún modo, lo que quizá me permita diluir la tierra para que aparezca el mar.

Francisco Navarrete Sitja, Pineda de Mar, 2017

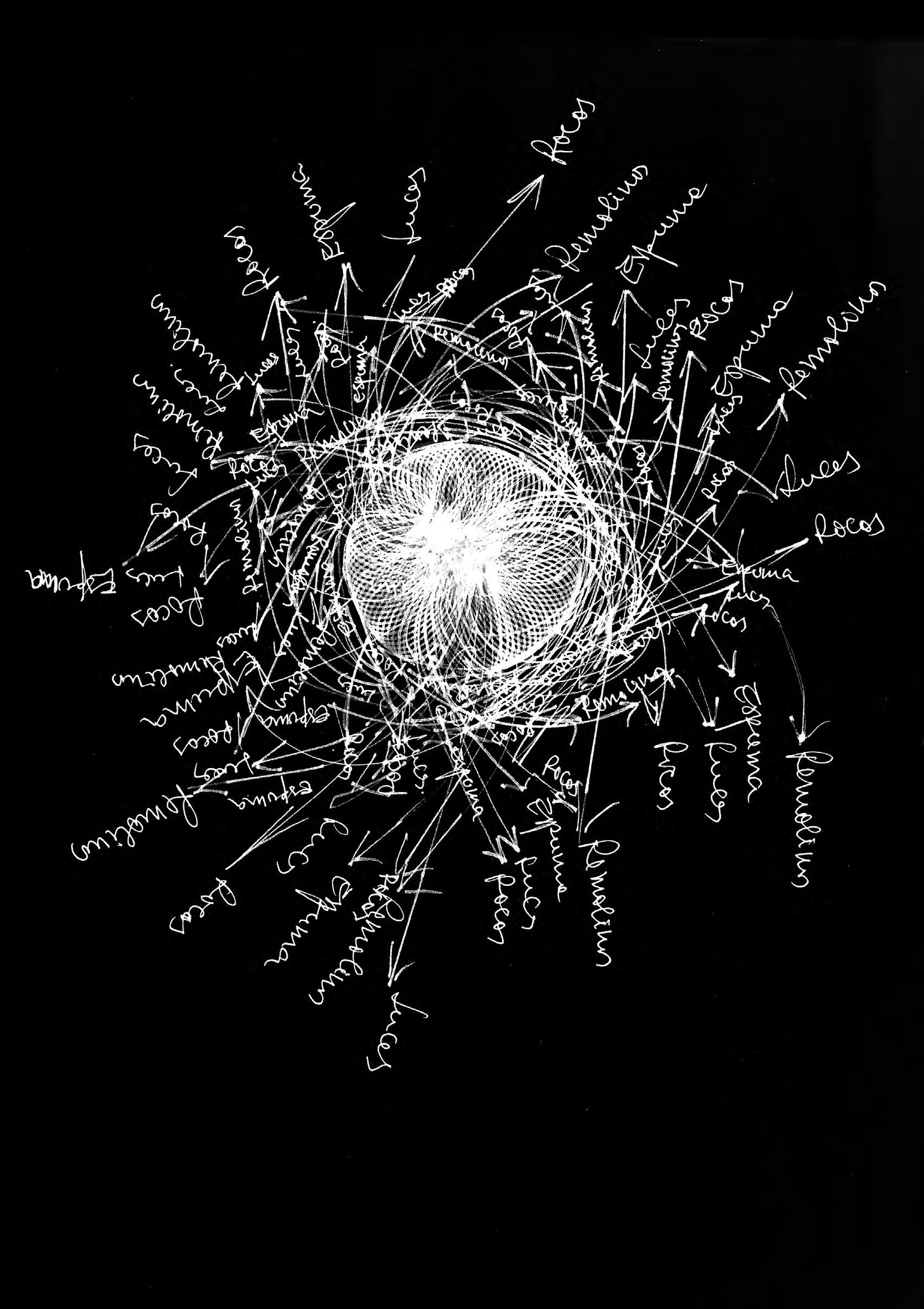

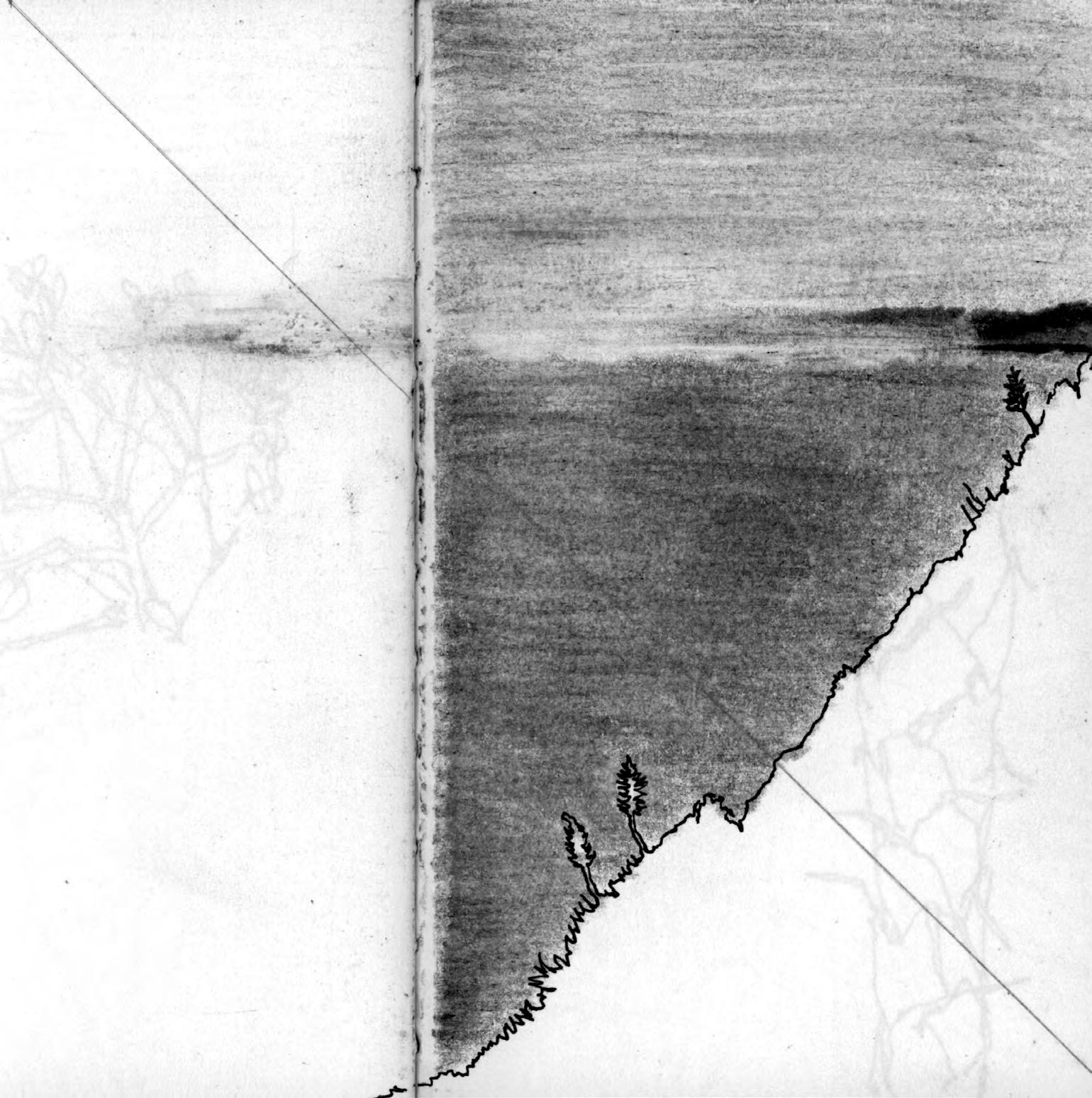

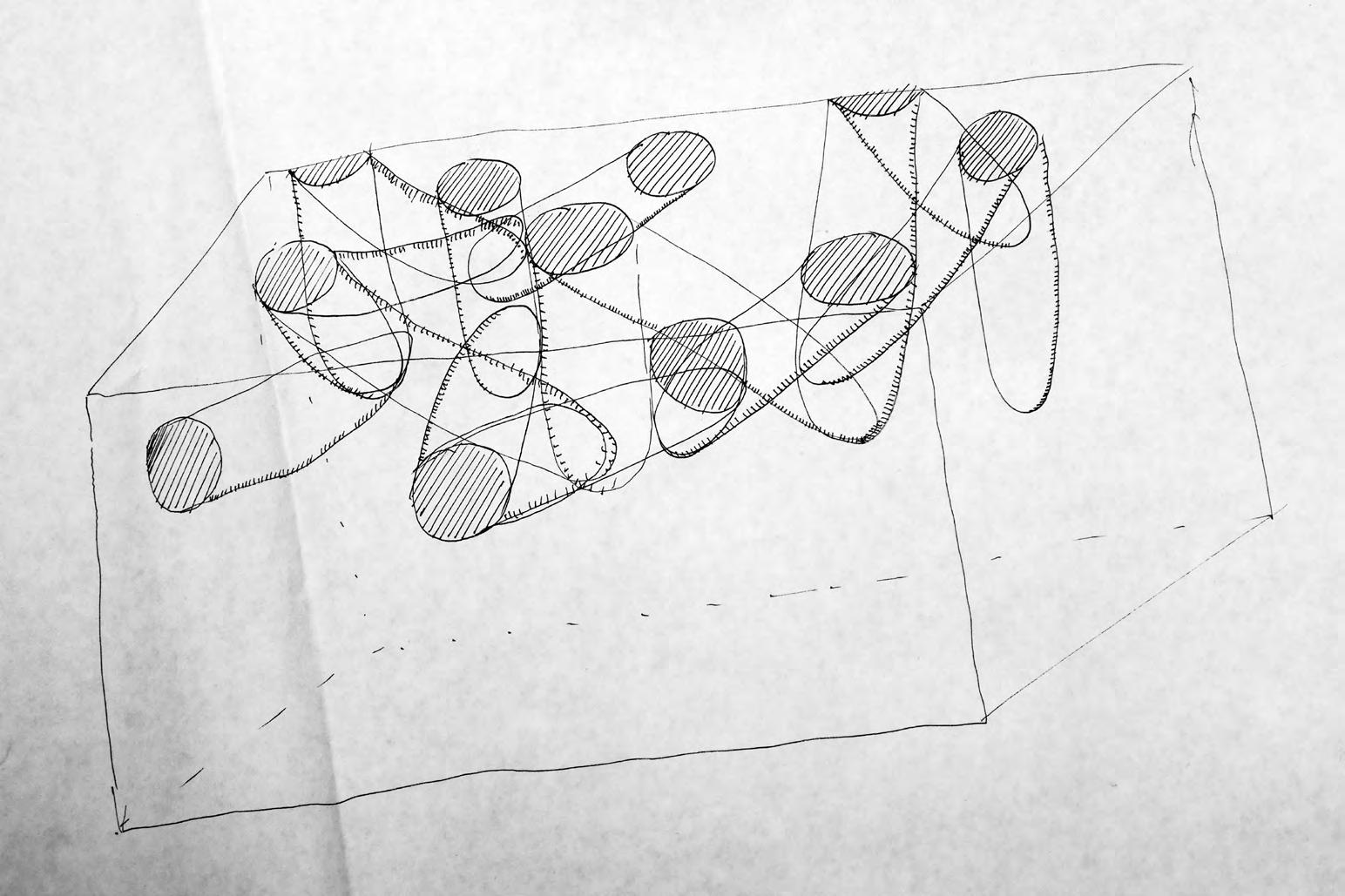

Serie Estallar la línea; diluir la tierra exploración y trabajo de cam po en Punta de Talca y Bahía de Coliumo. 2016-2017.

Pág 17

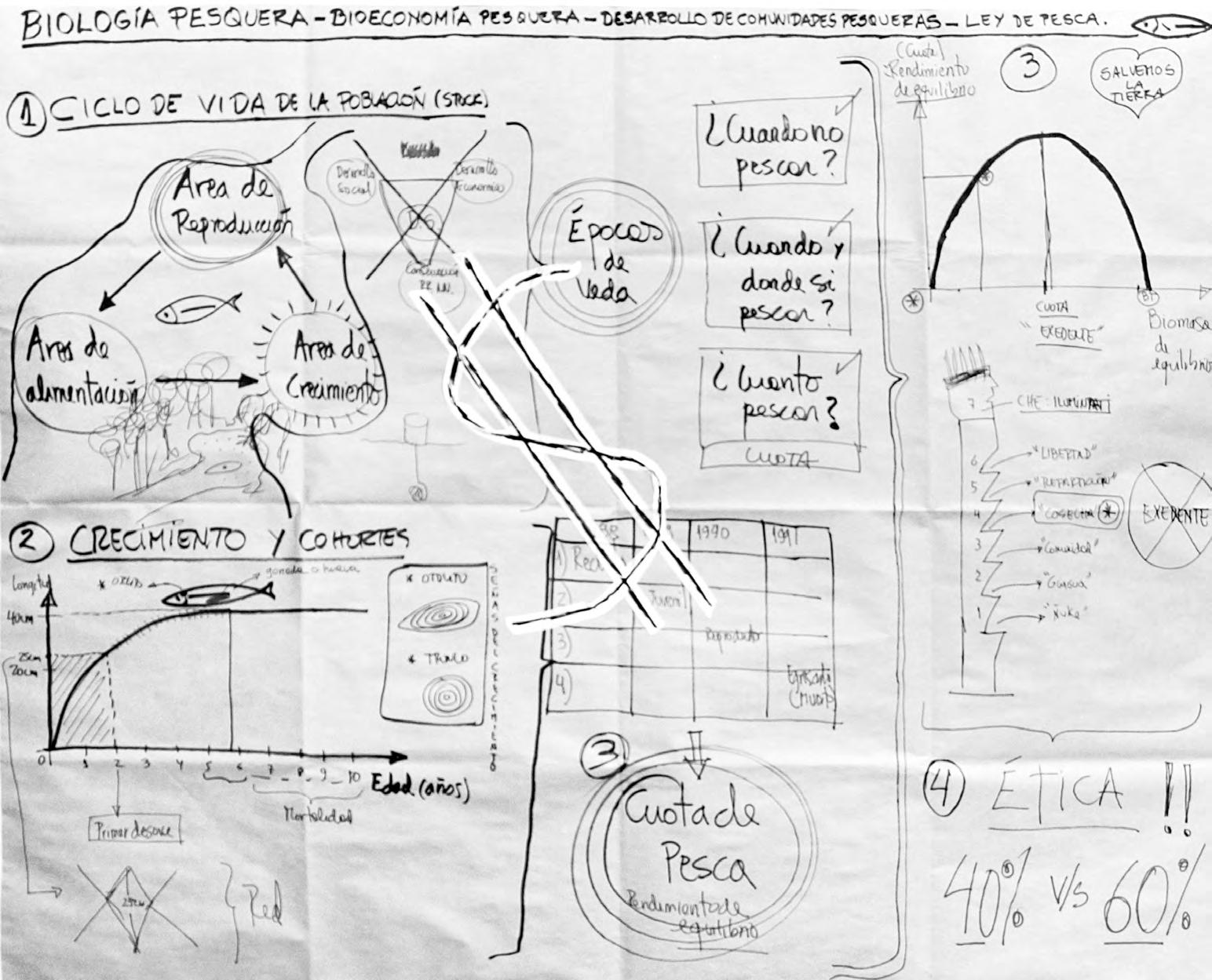

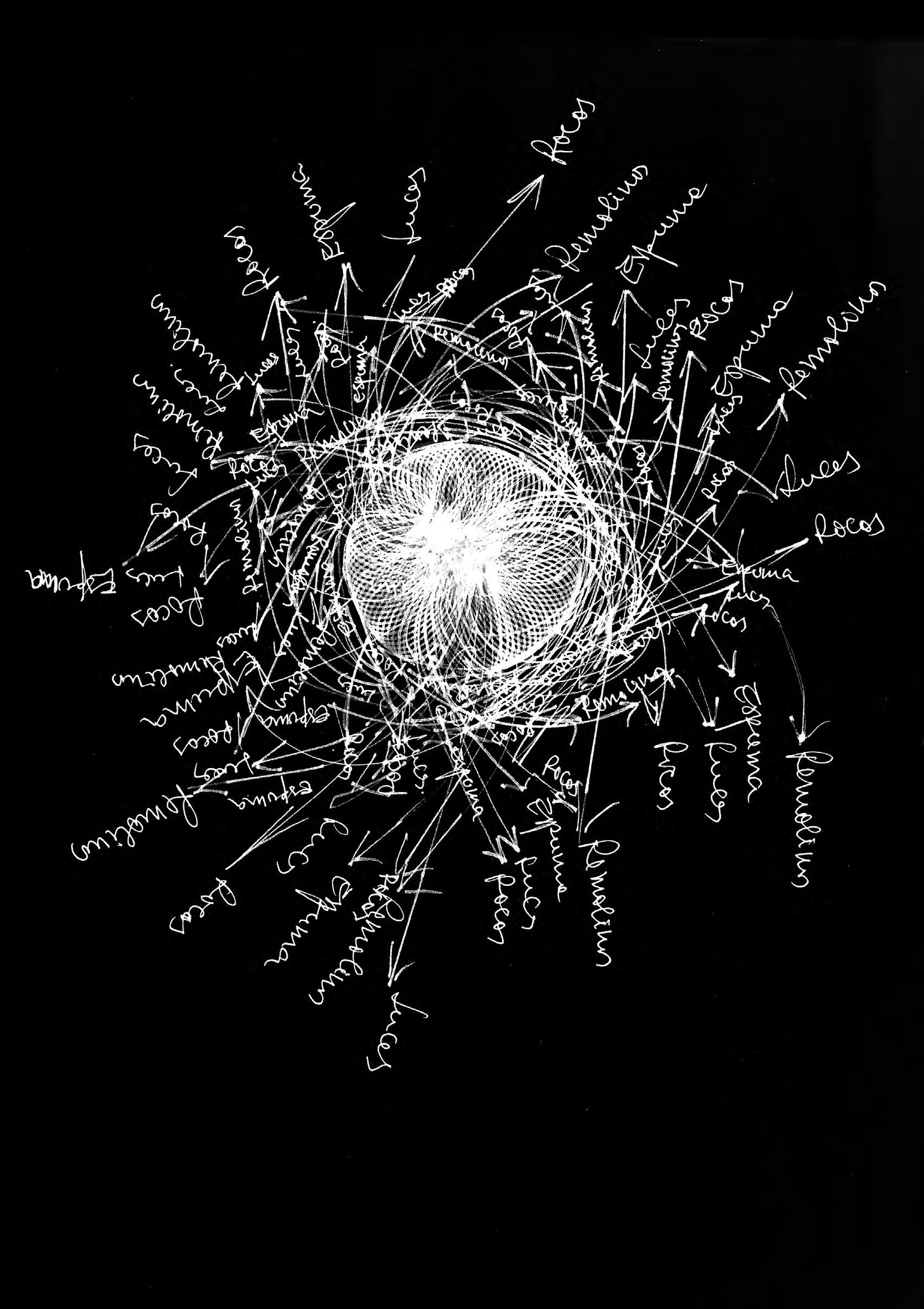

Representación gráfica y signo esquemático realizado por el artista durante proceso de diálogo con el Oceanógrafo Osvaldo Ulloa.

Pág 19

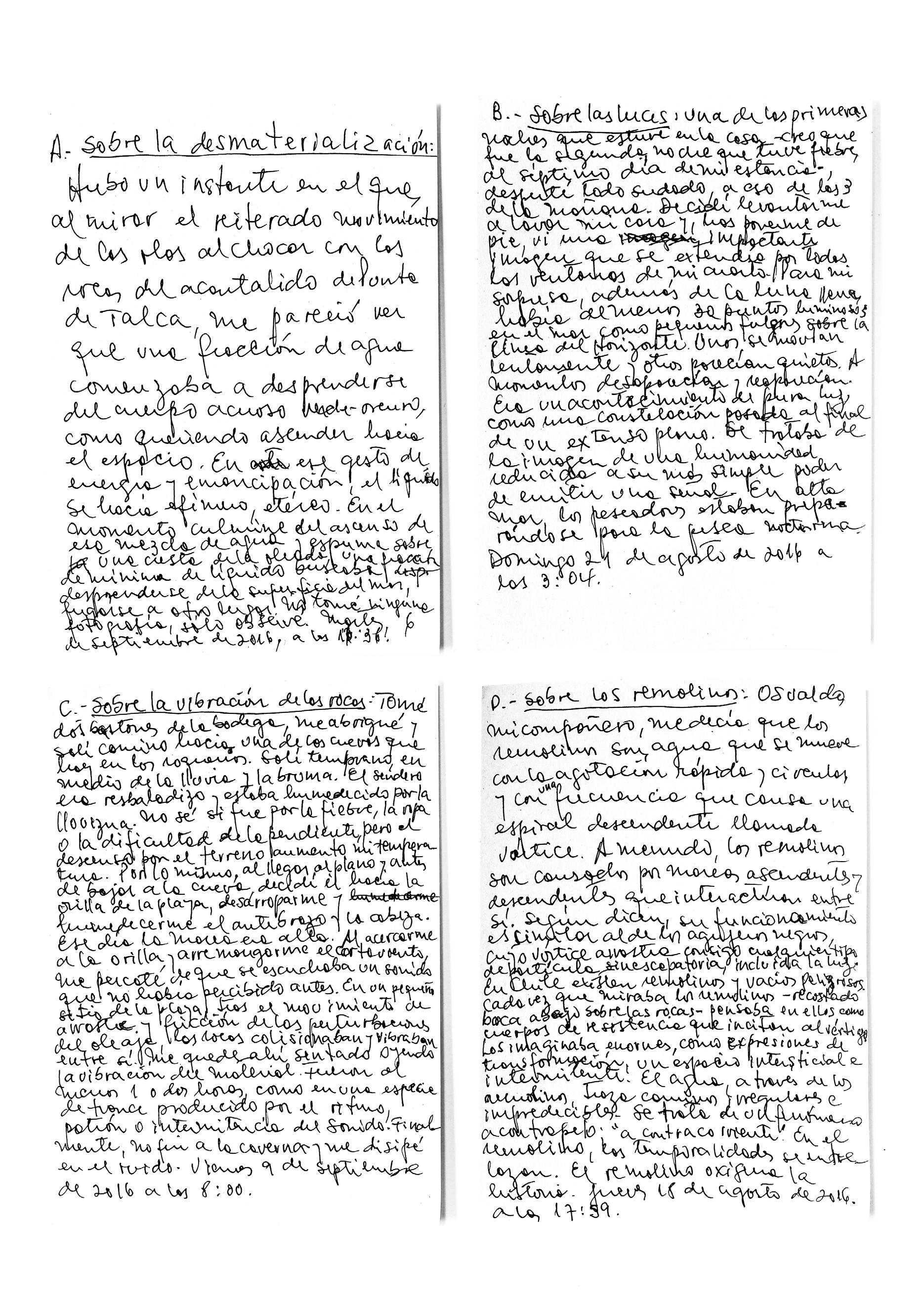

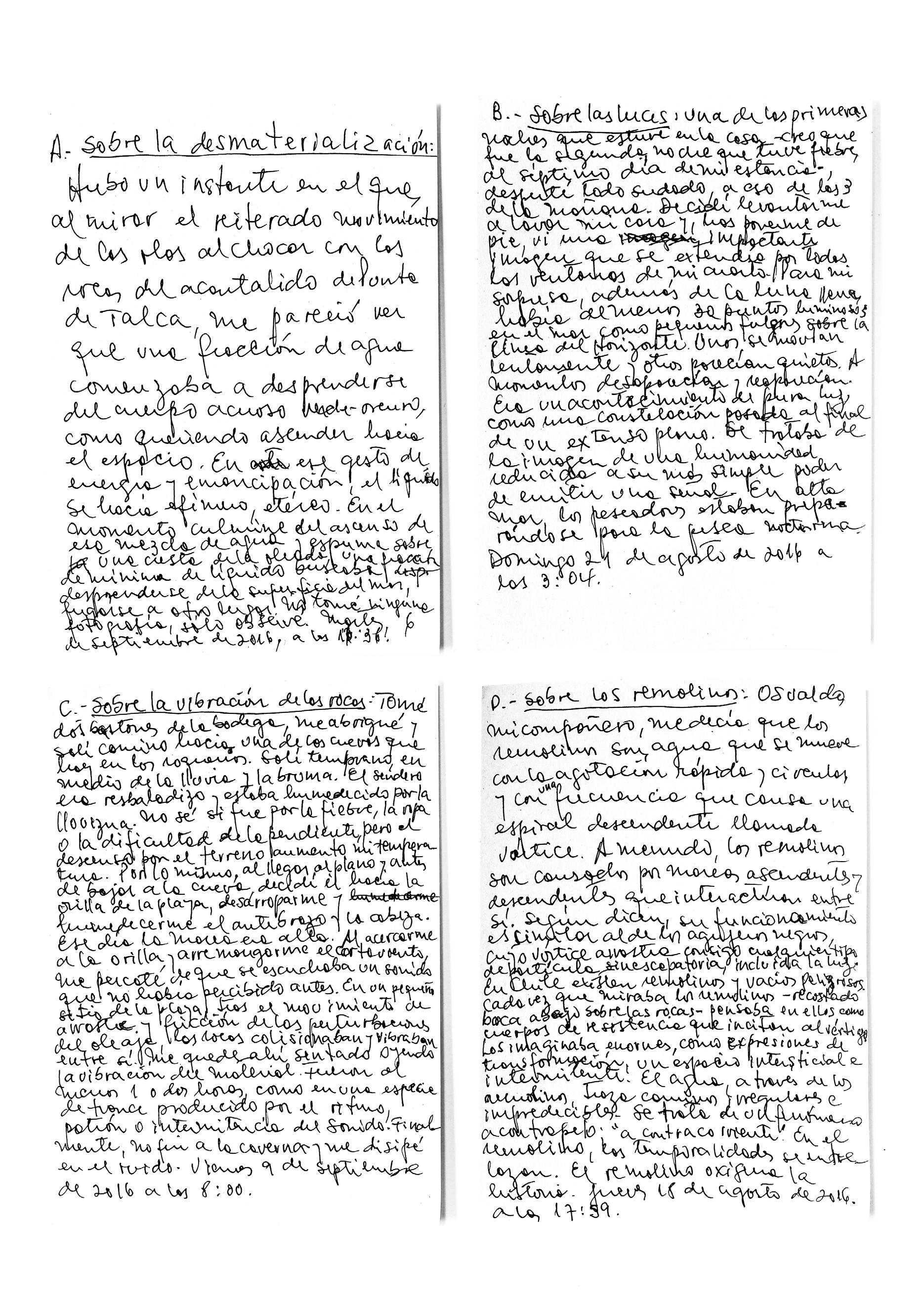

Fragmentos de Bitácora de trabajo de campo sobre desmaterializa ción, luciérnagas, remolinos y vibración de las rocas, entre otros. Serie de anotaciones realizada por durante diálogo con el Oceanógrafo Osvaldo Ulloa.

Pág 20-21

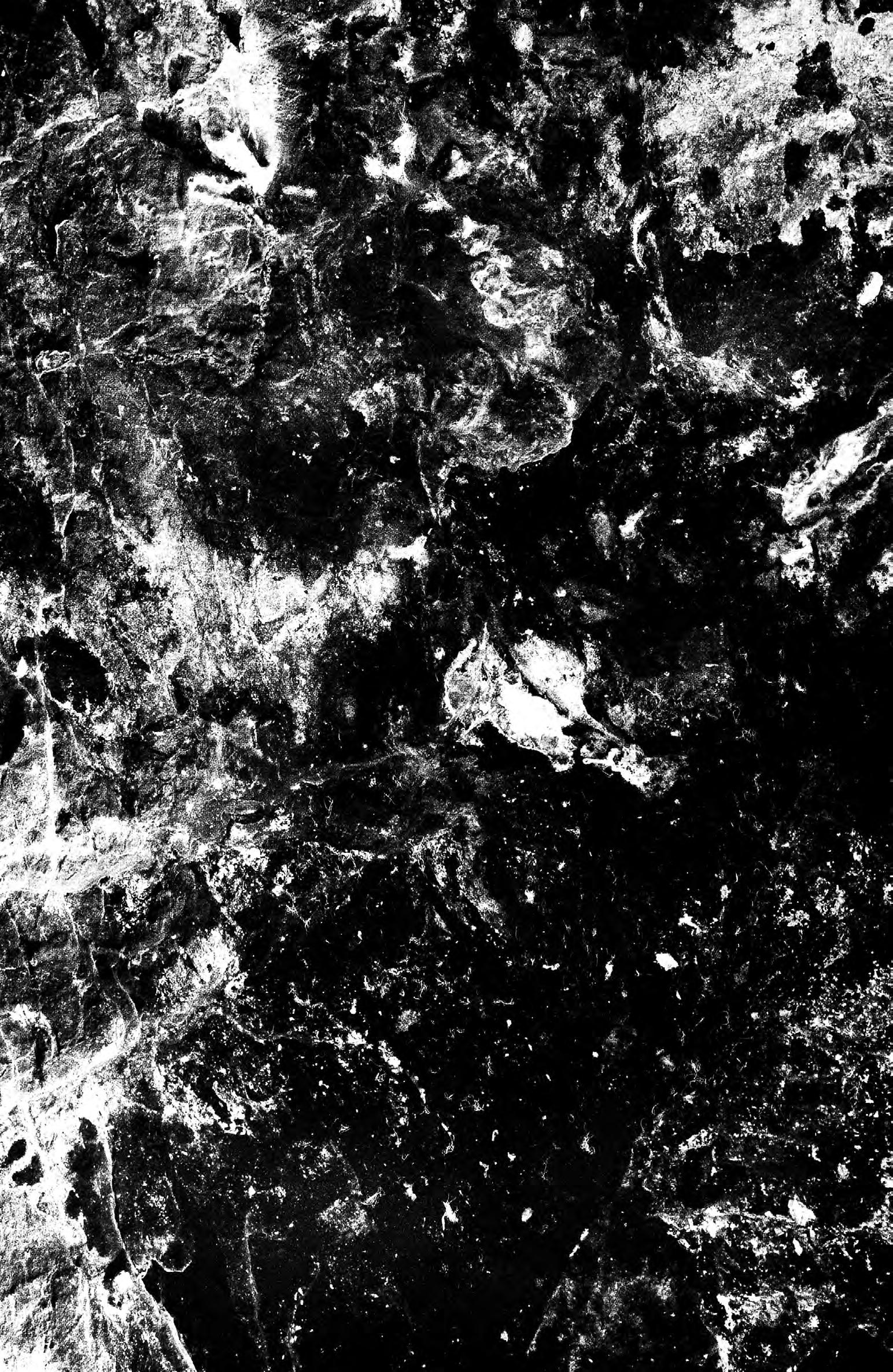

Selección del registro fotográfico realizado durante el proceso de diálogo con el Oceanógrafo Osvaldo Ulloa.

Pág 22

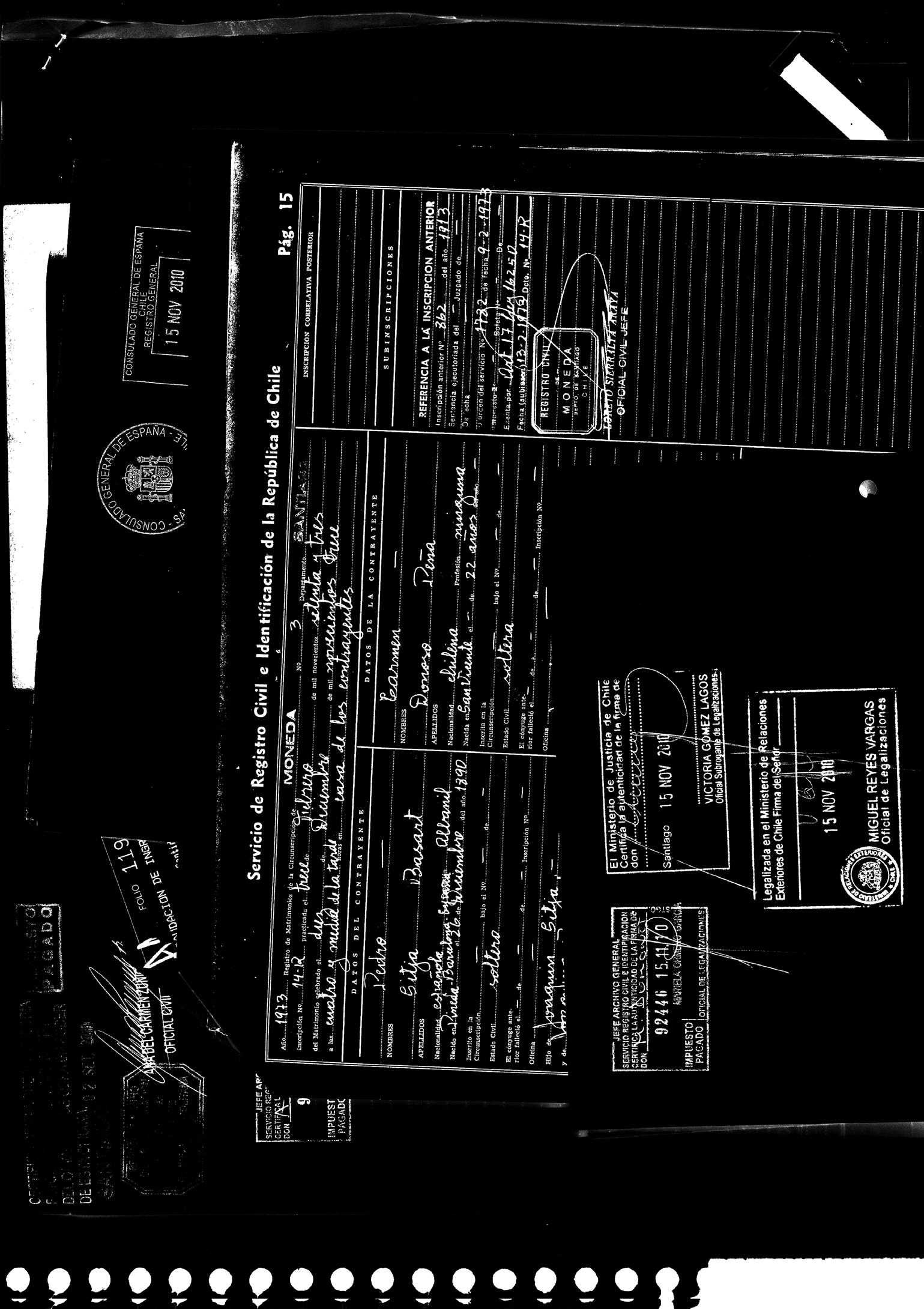

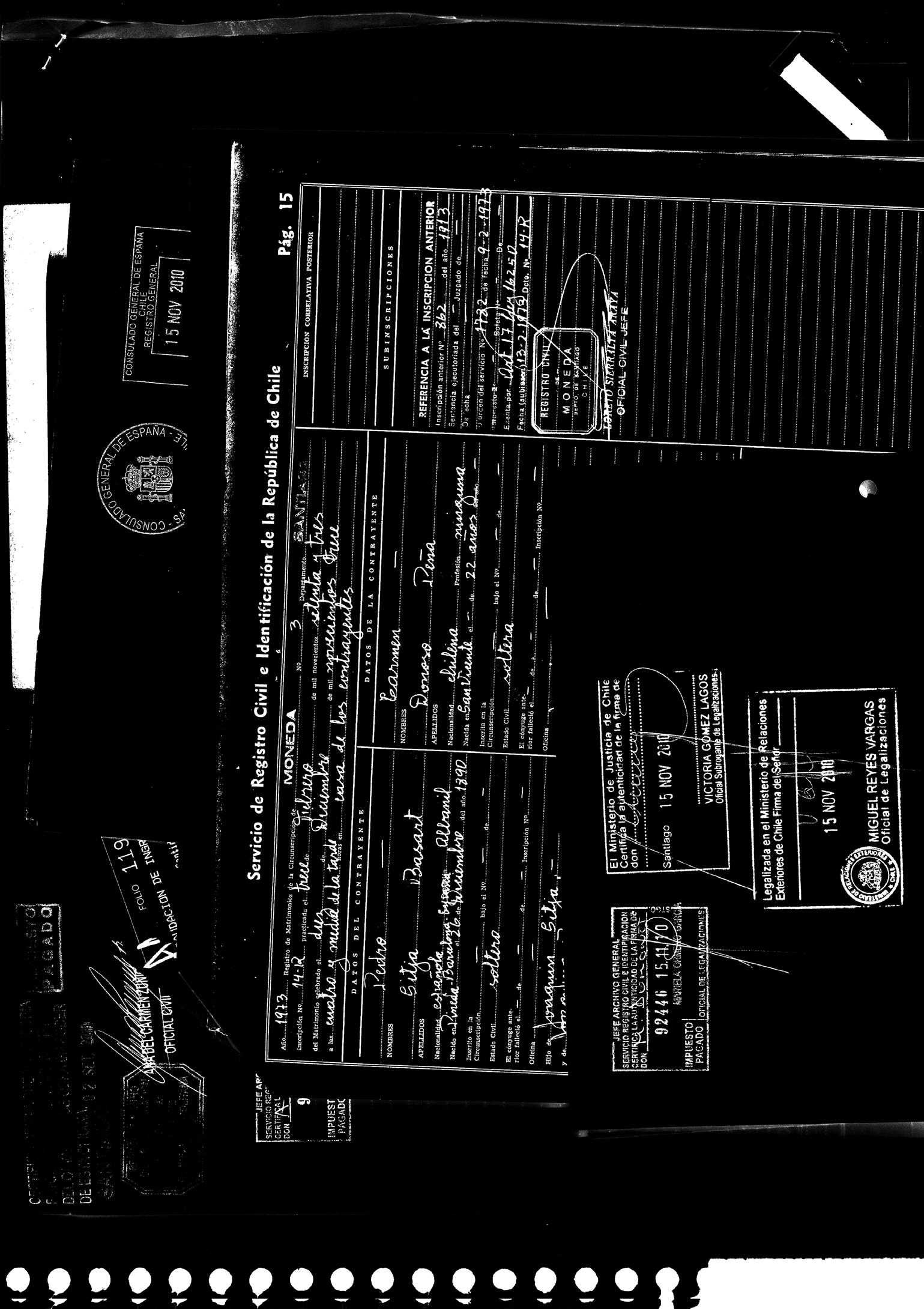

Material de archivo institucional digitalizado e intervenido. Compo sición de serie de certificados de inscripción del Servicio de Registro Civil e Identificación de la República de Chile, a nombre de Pedro Sitja Bazart.

Pág 23

Material de archivo encontrado, digitalizado, impreso e intervenido. Vista cenital del punto de encuentro de mar y rocas.

18

22 23

IN-SITU-ANDO

Eduardo Cruces | Artista Visual Andrés Tassara | Geólogo

Fuimos invitados para participar como dupla en el ci clo de residencias Territorio Compartido por Casapoli, instigadora de un cruce entre la investigación cien tífica y artística. En nuestro caso, la particularidad que motivó la invitación se basa en la vinculación entre nuestras disciplinas y su relación con la Tierra. Andrés como académico e investigador de las Cien cias Geológicas, Eduardo por su investigación en las cuencas carboníferas iniciada desde la Península de Arauco.

Nuestra vinculación transitó diversas operaciones que reflexionaron constantemente sobre la me todología de la propia planificación del proyecto, donde jamás lo primordial fue generar un producto final, sino más bien las condiciones de socializar una serie de experiencias por dicho proceso en colabo ración.

La presentación inicial entre ambos consistió en un intercambio de textos publicados desde nuestras in vestigaciones, muchos de ellos generados también por un trabajo en red y colectivo que propiciaba su circulación, en específico documentos en línea por Andrés y catálogos de exhibiciones por Eduardo. Dichos textos sirvieron como introducción a la esta da por dos semanas en Casapoli en Coliumo, donde continuamos dibujando mapas a diferentes escalas, graficando con colores los tipos de rocas existentes en la zona. Desde allí, el nicho teórico y visual es materializado mediante salidas a terreno diurnas y nocturnas, donde Andrés verbaliza una serie de conceptos asociados a las dinámicas actuales que estructura el estado de aquello que nos rodea, hi lando palabras específicas que afloran como enlaces entre la metodología científico-artística. Entre otros,

el concepto “in situ” vibra transversalmente para am bas prácticas, convertido por nuestro experimento verbal al gerundio “in-situando” a propósito de re calcar un carácter procesual en el acto de encontrar y accionar en un mismo lugar, donde si bien no es obviada una particularidad del contexto, lo concibe en un estado de dinamismo continuo.

Dicha sintonía es potenciada al toparnos con un punto importante en términos conceptuales, una cita de Ghyka que hiciera Mauricio Pezo, dentro del libro donde a su vez expone el proyecto arquitectó nico de la propia Casapoli, definiendo así el paisaje: “Toda estructura geológica local y las formas resul tantes que son el esqueleto del paisaje, representa rán el residuo, la huella cicatrizada de un conflicto de fuerzas naturales... un efecto que mucho tiempo después de la separación de la fuerza misma, evo ca una intensidad y fija su recuerdo” (89,91. pág. 11. Mauricio Pezo 89). Entonces ¿Un proyecto de crea ción sería dicha intensidad evocativa de otros pro cesos generados por una cadena de interacciones?

¿Las fuerzas naturales podrían ser también fuerzas culturales, fuerzas económicas, fuerzas del trabajo u otras fuerzas en conflicto? ¿Sirve esta reflexión como metáfora de nuestra propia experiencia creativa? ¿Es así el paisaje y su sustrato geológico a la obra culmi nada lo que las fuerzas dinámicas inmanentes lo son al proceso creativo? ¿Resulta mucho más relevante entonces el proceso por detrás de la obra que el pai saje generado por éste, la obra misma?

Posterior al periodo de interacción en Coliumo, se articula una serie de reuniones en la oficina de Andrés en la Universidad de Concepción, donde ensayamos un guión para una charla pública, con

ABSTRACT

Palabra clave: Imagen

La presente investigación hace lectura desde la obra Ga lileo Galilei de Bertolt Brecht, Acto “VIII Un Diálogo”, entre el científico y un monje.

GALILEI: A veces pienso: me haría encerrar en una mazmorra a diez brazas bajo tierra, a la que no llegara más la luz, si en pago pudiera averiguar lo que es la luz. Y lo peor: lo que sé tengo que divulgarlo. Como un amante, como un borracho, como un traidor.

24

ABSTRACT

Palabra clave: Condiciones

La presente investigación interpela las condiciones del artista y del científico en un sistema que subyuga la relación entre humanidad y naturaleza bajo las lógicas del mercado. Dicho cuestionamiento debe considerar también la separación del trabajo y la externalización de costos.

ABSTRACT

Palabra clave: Socialización

La presente investigación centra su importancia en las operaciones que cruza un proyecto articulado en sus estrategias de socialización en un campo acotado de gestos. El objetivo no es la consumación de un enlace, sino identificar instancias específicas de transmisión que materialicen la fruición de una dinámica, prestando especial atención en los vestigios de dicha experiencia a medida que se transforma.

el propósito de ordenar la multiplicidad de puntos presentados a una audiencia en su mayoría acadé mica y proveniente de geología y artes visuales. La charla montada en el Auditorio de la Facultad de Ciencias Químicas se acerca al público desde diversos flancos: 1. Un sonido se escucha en todo el salón, ejercicio sonoro realizado junto al artista Francisco Navarrete Sitja, concebido por arrastre y frotado entre dos piedras en la playa de Coliumo, captadas mediante micrófonos adheridos a sus su perficies. 2. A medida que entran las personas, se les proporciona una ficha para redactar una pre gunta motivada del diálogo. 3. Al fondo, se proyec tan diapositivas con imágenes y diagramas de los puntos de vista por Andrés y Eduardo con respecto de la residencia, haciendo énfasis en las conjun ciones y divergencias propias de una experiencia transdisciplinar. 4. Casi al cierre y previo a las pre guntas abiertas de los asistentes, ambos leemos de manera alternada una serie de interrogantes escri tas en clave poética, con el objetivo de extrapolar una apertura centrada en la duda por sobre la cer teza, dichas preguntas también se proyectan sobre el fondo durante la presentación.

La charla es asumida como una retroalimentación vi tal en directo, donde tensionamos junto a la audien cia las interrogantes motivadas por una interacción que así lo requerían. De esta manera, la etapa de circulación del proyecto puesta en esta publicación sitúa la lectura como una siguiente instancia que tra tar: ¿Cómo generar las condiciones para que el lec tor se inserte en una dinámica de experiencias con el proyecto, en la medida que lee y hojea un libro impreso? ¿Cómo evocar a través de sus vestigios, la intensidad de dicha experiencia?

En la dinámica actual de socialización hemos pro ducido un texto y diversas imágenes. El texto está narrado en clave metafórica por una serie de resú menes junto a sus palabras clave, similares a los dis puestos al principio de los documentos académicos convencionales, esta vez introduciendo ciertas te máticas posibles para ser abordadas. Las imágenes corresponden a un montaje de registros visuales generados a través de todo el periodo de vincula

ción, diálogo y colaboración entre todas las inte racciones del proyecto, y del cual no tenemos total certeza en los efectos e instancias que continuarán acaeciendo por la sintonía iniciada y las fuerzas ya liberadas.

ABSTRACT

Palabra clave: Verbalizar

La presente investigación transita directo a las zonas de sacrificio que habitan dichos paisajes donde la omisión es ejecutada como castigo sobre sus propias comuni dades. Sin embargo, desde el silencio forzado también actúa una progresiva interiorización de las experiencias, allí donde el mundo se arma como un gran secreto, del cual es posible disparar sólo con verbalizarlo.

28

ESE MAR QUE TRANQUILO NOS BAÑA

Gonzalo Cueto | Artista Visual Alvaro Espinoza | Biólogo

La crisis de la pesca artesanal en Chile se alarga ya por demasiado tiempo. Vivimos en la regencia de le yes diseñadas para mantener artes de pesca dañinas para el ecosistema marino y para reservar amplias cuotas de pesca para las corporaciones industriales. Vivimos en la ignominia de tener que asistir al desta pe de los escándalos de corrupción con parlamenta rios mojados y pauteados por la industria, y funcio narios públicos con altas responsabilidades políticas directamente sobornados. Vivimos en la angustia de los pescadores artesanales y sus familias azotados por las mareas y por la autoridad marítima que, por la fuerza, controla, sanciona e impide que los pobres accedan a pescar lo que su subsistencia demanda. No hace mucho tiempo para los pescadores era un orgullo que sus hijos fueran la primera generación que se estaba educando en institutos profesionales con los pagos mensuales por una educación de baja calidad y que, que por cierto, salían de la abundan cia de la pesca. Hoy es penoso ver la desesperanza de los pescadores al ver que sus hijos ya no podrán siquiera tener la ilusión de una educación superior que los haga emigrar hacia otros derroteros labora les. Asistimos a los días en que todos van a la playa pero no miran lo que ocurre a su alrededor. Asisti mos a los días de la extinción de la cultura costera, los mariscales, la carpintería de ribera, los botes me ciéndose juntos en las bahías, las procesiones y la risa de los niños jugando encima de las cubiertas de los botes varados.

biológicos y económicos de la crisis y de cómo el Gobierno no ha respetado las pautas internaciona les elementales para garantizar la conservación del patrimonio biológico de la nación y, mucho menos, el acceso igualitario a la pesca. También realizamos entrevistas a dirigentes de los pescadores las que registramos en videos, los que editamos y presen tamos ante la asamblea del Sindicato de Pescadores de Coliumo. De esta forma se pudo iniciar un inte resante debate donde quedó registrada la angustia de los pescadores por la actual situación productiva y social que viven. A la hora de la discusión de las soluciones a la crisis la asamblea tuvo un giro inespe rado. Frente a una respuesta negativa del residente científico para apoyar una campaña de matanza ma siva de lobos marinos (a quienes responsabilizan por su mala pesca ya que les comen las presas atacando las redes) se produjo una catarsis hacia la profesión de los biólogos marinos a quienes achacan ignoran cia de los fundamentos de la pesca y responsabili zan por su actuación antiética en el sistema público que finalmente los perjudica como trabajadores de la mar.

Asistimos a unos días en Casapoli para ver que nos pasaba estando allí cerca de las comunidades cos teras y su entorno. Y pasaron muchas cosas. Los residentes tuvimos brillantes sesiones de análisis de cuestiones técnicas de los detalles pesqueros,

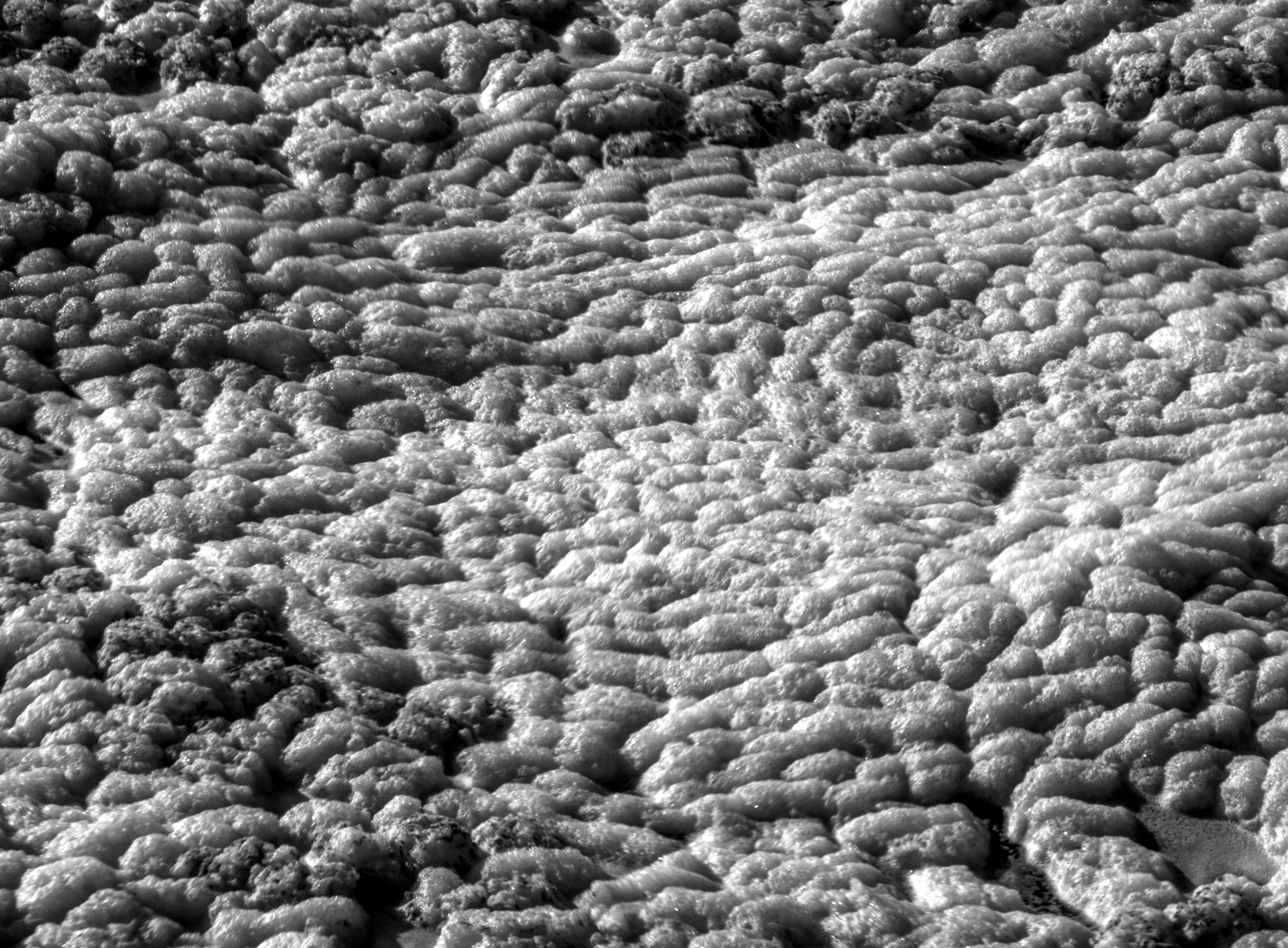

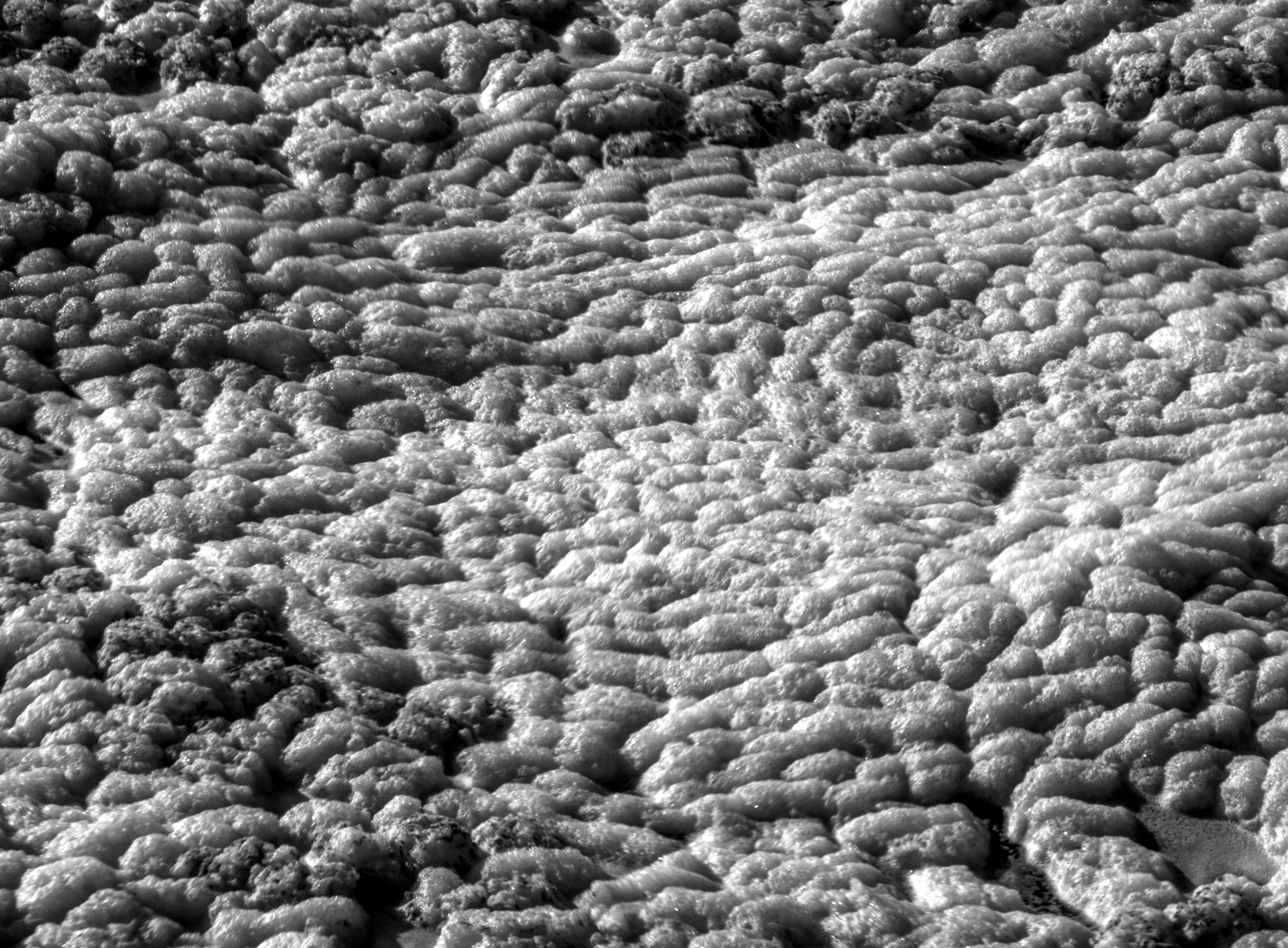

El correlato artístico de toda esta vivencia emergió de forma misteriosa plasmándose en registros au diovisuales de la organicidad de las espumas bio lógicas de los furiosos requeríos de Casapoli y en el paso avasallador de gigantescas moles navieras atiborradas de contenedores donde se exportan los productos de una economía local basada en grandes volúmenes de recursos naturales con tipos de pro cesos industriales que resultan en productos que no explotan toda su capacidad de elaboración; perdien do con ello la posibilidad de obtener el mayor valor agregado posible y la mayor empleabilidad indus

trial. Es decir, una forma de producción sustentable que despresione la explotación por volumen de los recursos pesqueros y garantizar con ello su conser vación.

Qué lejos estamos de una forma honesta y susten table de administrar nuestros recursos naturales pesqueros. Qué débil se escucha la voz de las co munidades costeras frente a ello. Qué desesperan za la registrada. Qué caldera de conflicto social se incuba entre los pescadores y sus familias. Cuánta

indolencia frente al sufrimiento de las comunidades costeras. Cuánta labor puede hacer el arte contem poráneo para visibilizar este sufrimiento y las salidas de la crisis por la vía de un empoderamiento de los pescadores de su destino marítimo de frente a la in justicia del discurso oficial basado en leyes lógicas, biológicas, pero mentirosas y a favor de los podero sos. Si en la historia de Chile hubo una reforma agra ria en contra el latifundio y el inquilinaje oprobioso también puede haberla para poner las cosas en su justo orden en el mar que tranquilo nos baña.

32

33

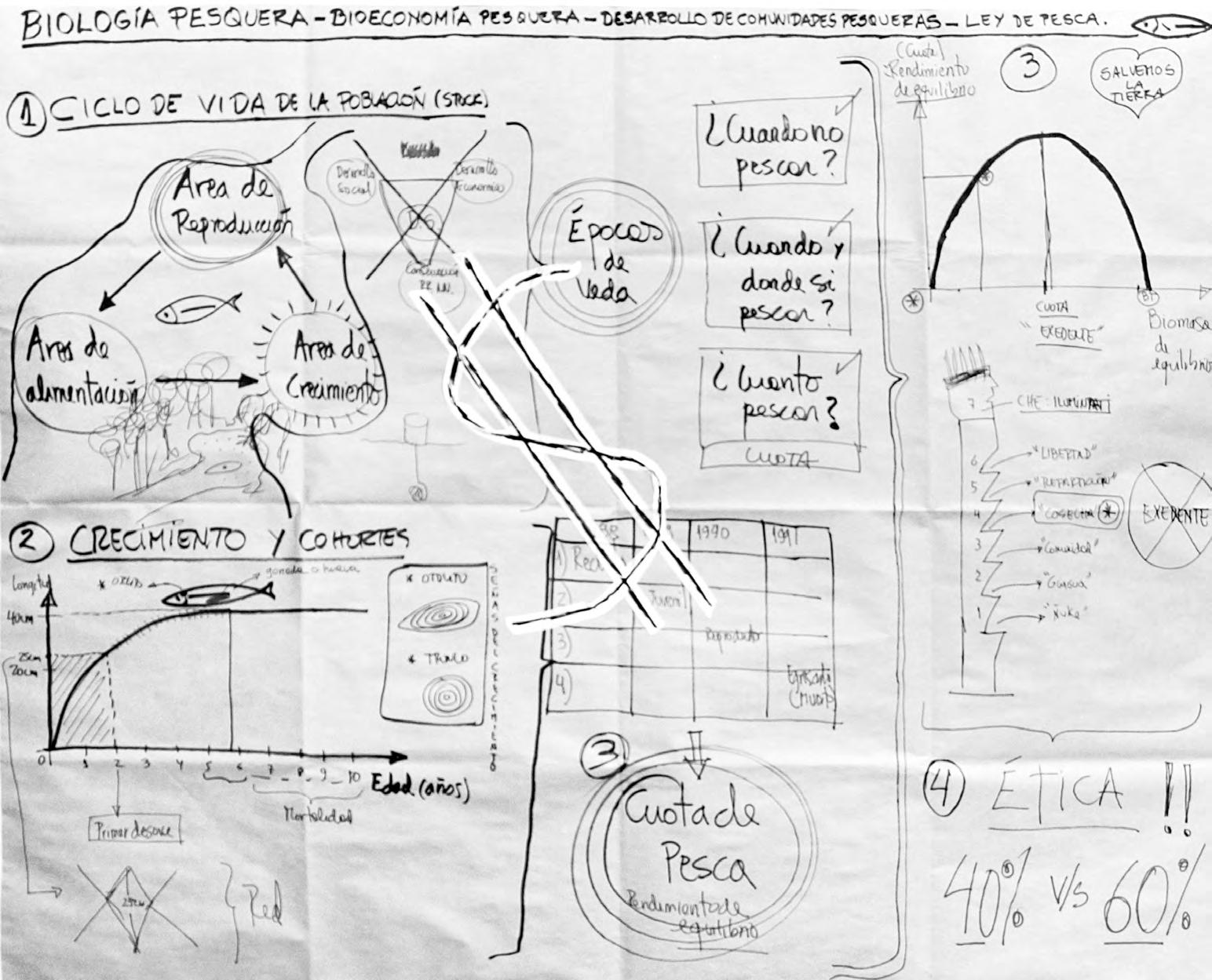

Pág 33

Papelógrafo de planificación del proyecto Ese mar que tranquilo nos baña Registro Gonzalo Cueto.

Pág 34

Carpinteros de ribera y faena de extracción de eucaliptus. Registro Gonzalo Cueto.

Pág 35

Contenedor en sector Vegas de Coliumo. Registro Gonzalo Cueto.

Pág 36-37

Espuma de mar, sector Punta de Talca. Registro Gonzalo Cueto.

34

35

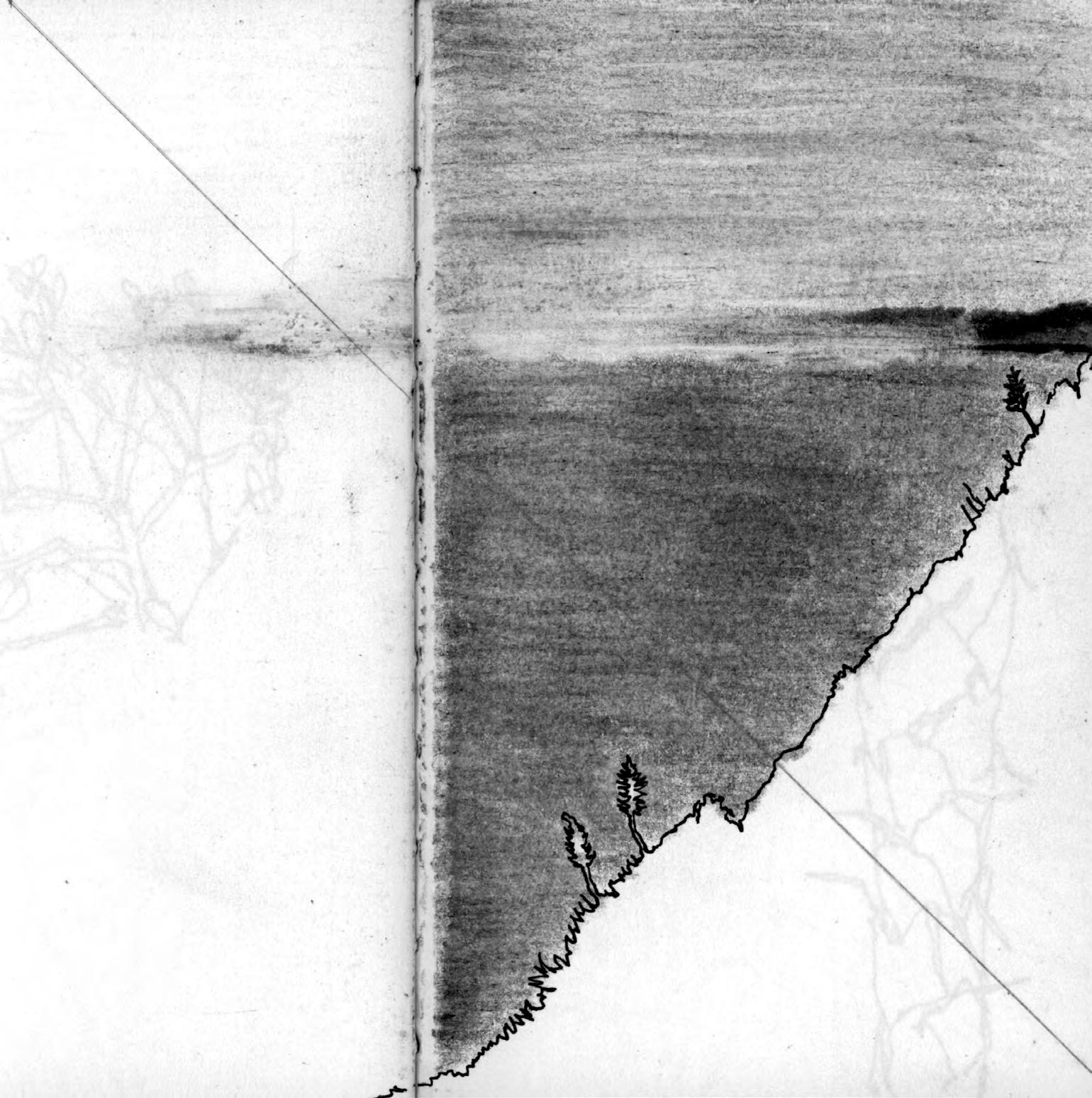

PAISAJE, TERRITORIO Y COMUNIDAD

Alejandro Quiroga | Artista Visual Javier Ramírez Hinrichsen | Historiador del Arte

En la actualidad (Chile), las experiencias artísticas han tomado una distancia relevante de lo que se entendía casi desde un lugar común, de la labor del artista. La obra de arte ya no pasa a ser el centro y el fin de la producción visual. Más bien nos acercamos a los con textos y condiciones con las cuales dicha producción, resultante en una obra, se constituye como tal.

La experiencia de residir fuera del confort del espacio del taller inicia su tránsito hasta la actualidad desde los inicios del siglo XIX en el ámbito europeo. Los ava tares de las transformaciones económicas producto de la revolución industrial repercutirán en la posición social, en el caso ocupado, de los pintores y su mundo.

¿Qué pasa en América Latina? En el texto “El artista viajero-cronista y la tradición empírica en el arte la tinoamericano posterior a la independencia” 1 del norteamericano Stanton Loomis Catlin (1915-1997), expone la llegada de una nueva forma de represen tar el continente americano. Con la llegada de los viajeros-cronistas (Debret, Rugendas, entre otros) se abre una nueva mirada sobre dichos territorios. Un poco más adelante se constituiría la representación del paisaje como problema pictórico. No podríamos hablar de una especie de tradición visual respecto de los artistas viajeros cronistas con el tema que nos convoca: la residencia en Casapoli (Coliumo), del artista chileno Alejandro Quiroga. Al contrario, hay ciertas constantes que no dejan de estar presentes, y son a la vez, prácticas que vuelven a resituarse.

Ahora bien, un historiador del arte local y un pin tor. La residencia de Alejandro Quiroga lo marca (y marcó) el paisaje. Al decir, península de Coliumo es indicar su bahía, las playas (también Dichato). No

obstante, esta punta que se introduce en el pacífico permite marcar un lugar.

Estamos frente a diversas imágenes; una caleta de pescadores, un balneario privado, etc. Para Alejan dro, dichas condiciones se entrelazan con trabajos que ya ha realizado. Ir más allá de una crónica pin toresca es su afán. Busca la forma de su atmósfera, su paisaje.

El lugar que rodea a Casapoli está lleno de señas. En la memoria reciente nos remite a poner la mirada en los vestigios pos 27 de febrero de 2010; campa mentos de emergencia, y en la bahía homónima a la península, casas de un proceso de reconstrucción. Producto de dichas circunstancias se define un nue vo paisaje, el pintor lo encuentra.

Por lo anterior, abordaremos tres tópicos para nues tra reflexión: paisaje, territorio y comunidad. Así iniciamos un diálogo que busca responder ciertos cuestionamientos de este sujeto (pintor) que lo re contextualiza en un nuevo lugar, la residencia.

Preguntemos, Alejandro, ¿qué entiendes por Paisa je?: “…Toda aquella superficie que me permite salir y entrar… campo propicio de exploración… natural o artificial…”

Sumemos, ¿qué entiendes por Territorio?: “…tiene que ver con el sentido de habitar este u otro paisaje… No todos los paisajes los considero mi territorio… “

Finalmente, ¿qué entiendes por Comunidad?: “… todo aquello que nos implica… una idea de colec tividad…”.

Hoy, la experiencia de un pintor en residencia en el borde del territorio continental americano, y fuera del centro político de Chile marca un con traste al respecto. Queremos seguir preguntando. De nuevo Alejandro, de la creación artística, ¿cuál es el lugar que tiene al frente o ante la realidad social de una comunidad?: “…es fundamental, por eso es clave el espacio público… Eso ya lo decía Camnitzer 2 , en el arte de espacios públicos se puede reflexionar frente a todo lo que los medios no informan: intervenciones públicas, trabajos de comunidad, etc…”.

La vivencia y experiencia de Alejandro en Casapoli traspasa el umbral del inmueble y aloja en un nuevo territorio. Estar ante el paisaje de Coliumo lo vuelve público, el territorio en espacio.

Hablemos entonces de la idea de residir. ¿Cómo un pintor puede ser huésped de un lugar que no le es propio?: “… El estar en otro lugar te permite poder hacer lo que normalmente no harías en un viaje fa miliar, por ejemplo… Registrar, experimentar y apre

hender un poco más del paisaje de lo que es a mi entender el centro de Chile...”.

Podríamos decir que existen en la residencia de Alejandro dos focos: uno plástico y otro político. La tensión de la transformación de ese paisaje vivido vincularía las dos variables enunciadas.

Justamente el trabajo de una residencia es ir al en cuentro de un contexto donde todo se tambalea, nada es fijo. La representación pictórica se constitu ye como una acción política. Ya no hay una mirada alterna, lejana; sino más bien cercana y situada.

Finalmente, la labor del historiador del arte a cons truir un relato a través de las imágenes y la memoria del pintor: Alejandro Quiroga. Traspasando las fron teras de la experiencia objetiva de los documentos nos adentramos en la vivencia de Coliumo y la cons trucción de su territorio como un paisaje cultural. No estamos ya más en el tiempo de las crónicas, sino del siempre aquí.

1 En: Ades, Dawn. Arte en Iberoamérica 1820-1980. Catálogo de exposición homónimo, Palacio de Velázquez, Madrid, 14 de diciembre de 1989 al 4 de marzo de 1990.

2 Luis Camnitzer (1937, Lübeck), artista uruguayo nacido en Alemania. Figura relevante para el conceptualismo en el arte latinoamericano.

38

Javier Ramírez Hinrichsen

39

Pág 39

Playa el Morro de Coliumo. Registro Alejandro Quiroga. Pág 40-41

Pintura de La Isla Quiriquina ubicada en la Bahía de Concepción, Alejandro Quiroga.

I

LA CULINARIA DE COLIUMO COMO HECHO SOCIAL TOTAL

Natascha de Cortillas | Artista Visual Noelia Carrasco | Antropóloga

Natascha de Cortillas | Artista Visual Noelia Carrasco | Antropóloga

La residencia en Casapoli estuvo centrada en el en cuentro entre las artes visuales y la antropología so ciocultural, cuyo objetivo fue idear y vivir el territorio de Coliumo a través de sus habitantes. Acercamien tos previos a la localidad permitieron visualizar en las mujeres algueras una agencia clave para com prender desde adentro las claves de su trama social vinculada al mar. En síntesis, la residencia permitió comprender el lugar de la culinaria local dentro de un sistema complejo mayor y más denso, cargado de tensiones y conflictos latentes y manifiestos, dentro del cual el goce de la comida adquiere también di versos matices. Esta configuración fue interpretada desde la inspiración intelectual de Marcel Mauss como hecho social total, categoría a partir de la cual logramos abordar a la comida como parte de un constructo ideológico y práctico, histórica y contex tualmente situado.

cer artístico. Ciertamente, el modo de aprehender y situar el acercamiento descrito no buscó reproducir las fórmulas clásicas de la etnografía. Aún cuando tuvo como base la observación directa y la perma nencia de las investigadoras en la localidad, la matriz epistemológica de la residencia no fue observar la realidad social en su estado natural, sino más bien reconocer sus fisuras y fracturas, sus implicancias internas y externas, su configuración a través de discursos que reflejan sentidos y cauces de conoci miento local.

II

Residencia - Trabajo de campo - reflexión metodoló gica: La perspectiva etnográfica como herramienta metodológica se instala como un ejercicio dinámi co entre las acciones planificadas por las residentes, permitiendo afinar operacional y teóricamente las prácticas que involucraban esta herramienta. Este campo metodológico sometió a revisión los límites de cada saber y abrió una práctica permanente en el encuentro con el otro, allí donde un saber teóri co, conceptual y por sobre todo humano, pudo ser generosamente compartido. Esta noción metodoló gica se comprendió como una herramienta cíclica, no lineal ni progresiva, capaz de levantar diferentes capas de sentido donde la contemporaneidad y la coetaneidad se configuran como espacios de convi vencia humana, conceptual y práctica en el queha

Lenguaje visual - Diferentes capas de sentido: Por ello los discursos que se levantan desde del arte tra man operaciones que no son inmutables, sino que están sujetos a los territorios. Cuando el arte toma este contexto social como un espacio de interac ción humana, más allá de un campo simbólico de representaciones, revela un cambio estético y cul tural que favorece “el encuentro” como un lugar de reconocimiento e intercambio y se asume como un dispositivo de conexión y cambio de la realidad. Allí el lenguaje del arte ejerce con visibilidad su ejerci cio transformador. Desde la etnografía antropoló gica, la potencia visual de la culinaria hace de ésta un lenguaje directo y tremendamente elocuente. El diálogo con el arte, propiciado por la residencia en Casapoli, interpeló, a su vez, a que la mirada antro pológica se enfrente a la necesidad no sólo de reco nocer otros lenguajes, sino también a construir un esfuerzo descriptivo mayor, pertinente a la densidad y complejidad de la situación vivida. Provocadas por los procesos flexibles, que rigen la vida en común de las mujeres algueras, se hicieron ejercicios de levan tamiento visual y sonoro respecto de la visibilidad y

42

activación de microhistorias que se urden en la con versación, el encuentro y la estada.

Contexto vinculante - áreas de interés vital- la bio política de la comida: Los acercamientos antropoló gicos a la comida y la alimentación han estado ba sados, desde sus orígenes, en una comprensión del hecho y proceso alimentario como una construcción social cultural y nutricional al mismo tiempo. Por este motivo es que en antropología contemporánea hablamos de lo alimentario y no de lo alimenticio, pues el eje de interés etnográfico no se centra en los alimentos y sus propiedades bioquímicas, sino más bien en las elaboraciones culturales de lo comesti ble, las transformaciones de los alimentos en comi das, y los significados, prácticas y sentidos asociados al consumo de alimentos y la comensalidad. Desde esta mirada se ha hecho posible identificar y descri bir las dimensiones políticas de la comida que refle jan los usos de la alimentación en las construcciones de la vida en tanto recurso civilizatorio y mecanis mo de control social. Esta dimensión biopolítica la pudimos identificar en la experiencia etnográfica propiciada por la residencia a través de dos aspec tos claves: el estatus que las mujeres asignaban a los saberes culinarios, y la incorporación progresiva de nuevos estilos de consumo, producto de la partici pación de estas localidades en transformadores y densos procesos de globalización.

Pág 43-46-47

Cocinería el Loro en entrevista y registro de las Cocineras. Registro Natascha de Cortillas.

Pág 45

Invitación de Marcela Sanhueza para compartir sus producciones culinarias. Registro Natascha de Cortillas.

Pág 45

Sobremesa en Casapoli. Invitación a grupo de Sindicato de Algueras Nº1 de Coliumo. Registro Sol Jorquera.

III

44

45

Daniel Cartes 04 y 05 de abril de 2017

Daniel Cartes 04 y 05 de abril de 2017

ESPACIO EDUCATIVO | ESPACIO POLÍTICO

Daniel Cartes | Licenciado en Arte

“…cuanto más fuerte es la organización molar, más suscita una molecularización de sus elementos, de sus relacio nes y aparatos elementales.” (Deleuze y Guattari)

Cuando Casapoli Residencias planifica en su proyecto un espacio para un taller de carácter educativo en un espacio formal, como lo constituye una escuela de educación básica del sistema municipal chileno en un sector semirrural de Tomé, está apostando por una ruta, una postura acerca de cuál debe ser el sentido de la producción artística que facilitan. Al fin y al cabo, se pone en una posición de compromiso y consecuencia política con quienes se relaciona. No es primera vez que Casapoli Residencias propicia el acercamiento con esta comunidad educativa, tanto es así que desde el año 2010 viene manteniendo, con distintos niveles de intensidad, un vínculo que asiste a las intenciones del proyecto educativo de la escuela Las Vegas de Coliumo de relacionarse con su entorno. La comunidad educativa, a su vez, ha comenzado a adquirir cierto acostum bramiento de ver y dar cabida a diversas manifestaciones artísticas, siempre dentro de un marco de ejercicio relacional y de lenguajes contemporáneos. Casapoli Residencias como un vecino.

EL TALLER

Después de la respectiva reflexión acerca de la historia de Casapoli Residencias en el territorio y sobre todo en el sentido del trabajo llevado a cabo por las duplas, cabe cuestionar, primero, si la figura del taller –amplia mente usada por su flexibilidad- sería la más indicada para proceder en la escuela, sobre todo si se considera a esta forma como un espacio en el que con las herramientas disponibles se configura un producto definido, fruto de un proceso de enseñanza/aprendizaje. Asimismo, estructurar el espacio sobre la base de transmitir cierto conocimiento conservando su hegemonía y posición dominante y vertical sobre los estudiantes, tam poco era el espíritu de los ejercicios propiciados por las duplas, ni por Casapoli Residencias. Es decir, seguir la tradicional y ordenada dinámica enseñanza-aprendizaje desde un programa previamente establecido estaba fuera de lugar y está lejos de representar lo que la teoría dice que es una buena educación. Acá, la duda fue recayendo en si era pertinente “enseñar” y sobre todo “enseñar sobre arte (lo producido por la duplas)”. Así, el convencimiento devino en un deber intervenir a través de otra fórmula, la cual debía ser políticamente conse cuente con el trabajo llevado a cabo hasta ahora. Situado en este marco de referencias, se planteó el espacio como un ejercicio experimental movido por el espíritu anticapitalista de las duplas, las que a través de diversas acciones intentaron traspasar poder (conocimiento y otros) a la comunidad local remeciendo e interviniendo en su orden habitual. De esta forma, la intervención en el espacio educativo debía tener como fin el traspaso de poder efectivo, el que en esencia es el fin de la verdadera educación, esa que boga por la autonomía del ser. Aquí la reflexión podría ser extensa, realizando apuntes desde el constructivismo, la emocionalidad u otras posturas vinculadas a la cognición, pero acá el problema se sitúa mas cerca de lo social (Freire) y sobre todo en el abordaje desde un criterio político-espacial para el diseño de la intervención (Rodrigo y Collados).

50 51

DESMENUZANDO EL ESPACIO

Al identificar y validar al grupo de estudiantes como poseedores de un conocimiento rico, valioso y, en esta ocasión, esencial desde la perspectiva del trabajo en territorio, implicó entenderlos como un par en este ejer cicio primeramente planteado desde lo educativo. Consecuentemente, la dinámica lleva a que la tradicional figura del profesor o guía se pierda y al mismo tiempo vea desjerarquizada la formalidad habitual, resultando en un planteamiento horizontal del espacio, es decir, había dos posiciones (en términos simbólicos) que te nían saberes relevantes.

La primera jornada buscó, a través de un mapeo colectivo, ubicar lugares significativos para ellos y propiciar la comunicación desde cosas y situaciones que ellos ya conocían. En el proceso se fueron incluyendo cajas con materiales que les iban desatando algunos problemas e incentivando el diálogo. En esta primera jornada, va quedando de manifiesto que el fin último de las residencias no es potenciar el entendimiento de obras, si no todo lo contrario, el de ir construyendo la idea de que los artistas producen más bien conocimientos y métodos. En este caso develando relaciones con el territorio de Coliumo.

La segunda y última jornada buscó materializar efectivamente el traspaso de poder al dejar a los estudiantes que comandaran ese espacio educativo a través de su exposición. Ellos ejercerían como profesores o guías del espacio, dejando en un rol de estudiantes a los profesores. Por un largo tiempo los estudiantes intentaron mantener la farsa facilitada por los profesores presentes, pero progresivamente se fueron develando hones tamente las normales relaciones estudiante-profesor (niño-adulto) aunque sin llegar a la formalidad habitual. Finalmente, y para sorpresa, el espacio se tornó horizontal y fue posible mantener una conversación abierta y honesta en torno a lo que nos iba surgiendo, siempre relacionado con su modo de apropiación del territorio.

¿Espacio conquistado? ¿Experiencia educativa exitosa? ¿Deben existir objetivos en el espacio educativo? ¿En qué lugar queda la experiencia artística? Y ¿Qué sería eso en este territorio?

Bibliografía:

Freire, P., (1999), Pedagogía para la autonomía. México DF, México. Siglo XXI. Collados, A., (sin fecha), Transductores: Pedagogías colectivas y políticas espaciales. Granada, España. Diputación provincial de Granada.

Deleuze, G. y Guattari, F., (2015) Mil Mesetas. Capitalismo y esquizofrenia. España. Pre - textos.

52 53

Pág 51

Presentación del trabajo de investigación del grupo de alumnos del taller realizado en la Escuela Vegas de Coliumo. Registro Daniel Cartes.

Pág 53-54-55

Participación de un grupo de alumnos en el taller realizado en la Escuela Vegas de Coliumo. Registro Oscar Concha.

54

55

Carla Motto

Victoria McReynolds

Xavier Tavera

15 al 31 de marzo 14 al 30 de mayo 02 al 16 de julio 02 al 16 de julio

Pablo Rivera

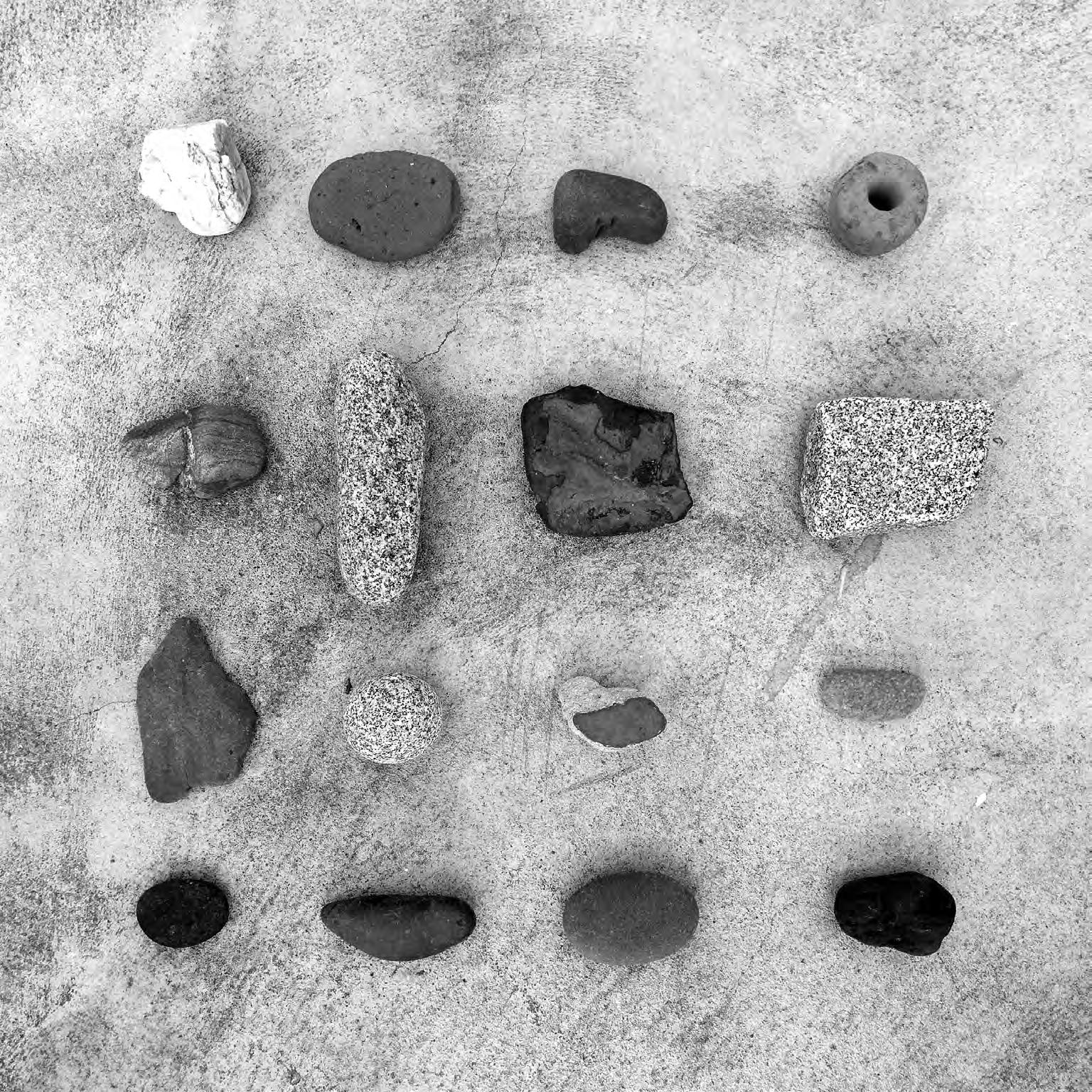

LA PIEDRA IDEAL

Pablo Rivera | Artista Visual

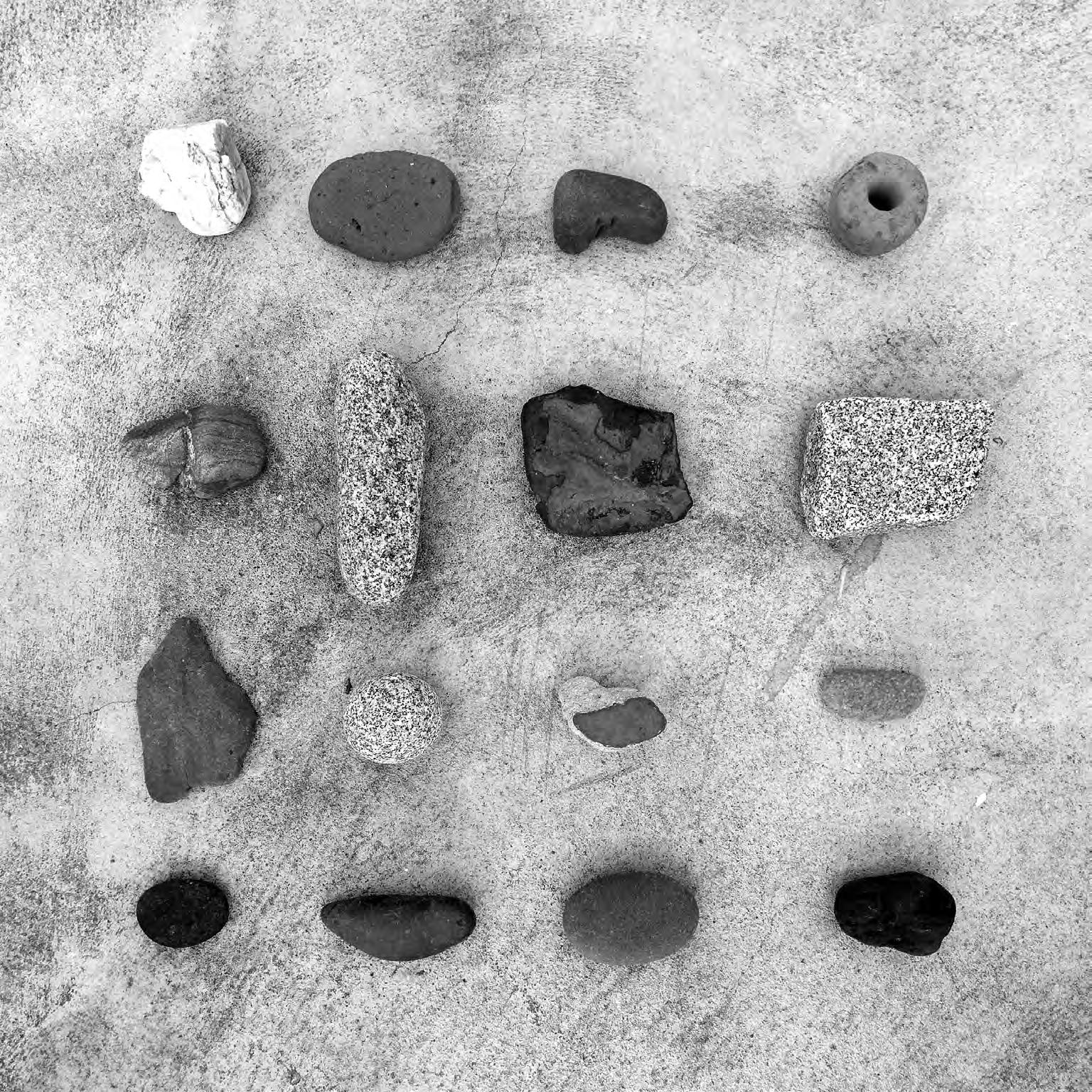

La piedra ideal es un proyecto que se remonta unos cuantos años atrás. Tiene que ver con que todos re cogemos piedras, algunos las juntamos y hasta las coleccionamos. Vamos a la playa, al campo o a la montaña y casi siempre volvemos con alguna pie dra. Me parece que en ello se construye una relación significativa con ese tipo de materias primordiales que nos son comunes a todos. Y, querámoslo o no, todos o casi todos aplicamos algún tipo de criterio para colectarlas.

Hace unos años intenté abordar el asunto: la idea era dedicarme un año entero a buscar y seleccionar pie dras en la calle basado en una rutina diaria. La me todología era muy simple: el primer día recogía una piedra que me atrajera y, al día siguiente, la debía cambiar por otra, colocando siempre a prueba una contra otra, destilando en ello los componentes que me harían llegar supuestamente, al cabo de un tiem po, a la piedra ideal.

Nunca terminé ese proceso pero la última piedra seleccionada me acompañó largo tiempo: deambu laba de aquí para allá, quizás como un modo de colo car en hibernación activa el proyecto. Era una piedra rugosa, de unos diez centímetros de largo, que cabía perfectamente en el puño de mi mano derecha. Su idealidad se basaba sólo en ello.

A fines del 2015 surgió la posibilidad de hacer una residencia en Casapoli, Coliumo. Su ubicación, en un pequeño balneario y caleta de pescadores- así como su condición de aislamiento, ofrecían condiciones muy favorables a un proyecto de este tipo. Allí no hay infraestructura técnica, no hay herramientas ni materiales a los cuales acceder con facilidad, pero

piedras y tiempo para examinarlas encontraría por montones.

Llegué a Casapoli sin mucha idea sobre qué meto dología seguir. Los primeros días sólo me dediqué a derivar por allí, a observar, a dejar que mi atención se fijara y obsesionara con su motivo. Ver piedras, palparlas, arrojarlas, registrarlas, referirlas a un con texto determinado. Entenderlas como material, pero también como cotidiano, como apropiación, como invisibilidad. A partir del tercer día comencé a visitar las playas del sector. En los alrededores de Casapoli hay varias caletas y playas: Cocholgüe y Playa Blanca por el sur; Necochea, Los Morros, Caleta del Medio en Coliumo y hacia Dichato, su larga playa y la Caleta Villarrica. Me propuse visitarlas todas.

El tercer día bajé a la Caleta del Medio y me interné por los roqueríos buscando piedras que me intere saran, con la idea de encontrar una y cambiarla des pués por otra y por otra, siguiendo la metodología que originariamente había utilizado. Pero resultó que empecé a encontrar piedras muy distintas. Me di cuenta de la elasticidad que la noción de ideal im plicaba, una categoría flexible y acuosa que se podía abrir en infinitas tipologías distintas. Ese día llegué con 15 o 20 piedras distintas y todas podían abrir un eje de proyección diverso.

Al cuarto día, por tanto, decidí enfocarme y dedicar me sólo a una tipología: las piedras redondeadas. Ese día fui a Playa Necochea y elegí las más redondas que encontraba. La cosa siguió más o menos así por tres o cuatro días y cada tarde volvía a casa con un saco de piedras: redondas, ovaladas, alargadas, unas de tamaño para lanzar, unas de tamaño para marti

58 59

llar, otras al punto de exceder la mano. Un día incluso me propuse encontrar sólo dos piedras idénticas.

Al octavo o noveno día encontré una piedra con ce mento adherido en su superficie, una especie de hí brido entre tekné y naturaleza. Este encuentro sería clave para entender lo que empecé a encontrar los días posteriores. Se trataba de algo similar a ladrillos, algunos redondeados otros más amorfos, pero to dos con incrustaciones de cemento. Entre revelación y posterior confirmación entendí que estos ladrillos eran restos del Tsunami que el 2010 había asolado la Bahía de Coliumo. Mi fascinación no provenía de la ruina, sino de su forma orgánica, de su equívoca apa riencia. Habían sido escombros de la destrucción:

pero el mar los tomaba de la playa y se los llevaba para arrastrarlos y desgastarlos en su fondo y luego devolverlos. Así, marea tras marea, se los volvía a llevar y devolver, así innumerables veces, por varios años, y con ello les iba dando forma de piedra. El mar los cambiaba, los ocultaba en una nueva apariencia. Interpreté ese movimiento como si el mar quisiera provocar una suerte de amnesia sobre los materia les; en unos cuantos años más borraría todo vestigio de su destrucción.

Me dediqué los días restantes a recolectar estos fragmentos, a arrebatárselos al mar para detener ese proceso amnésico. Para mí no hay otra piedra que tenga más relación con el lugar que éstas.

Pág 59

Piedras redondeadas sector Playa Necochea, Coliumo. Registro Pablo Rivera.

Pág 60

Primera recolección sector Caleta del Medio, Coliumo. Registro Pablo Rivera.

Pág 61

Registro de la zona sector Playa Cocholgüe. Registro Pablo Rivera.

60 61

CALAR – RECORRER

Carla Motto | Artista Visual

Experiencia del trabajo realizado:

El proyecto de intervención Calar - recorrer nace gra cias al encuentro con un pescador de 85 años que me sorprende con su sistema de pesca y entendi miento de la vida en el mar, Don Orlando Garrido.

Nos conocimos y generosamente me invitó a vivir junto a él la experiencia de la pesca artesanal. La es pero mañana a las 4 de la mañana, me dijo, traiga botas de agua y venga abrigada. Así comenzó nues tra travesía de varios días y noches, que más allá de una abundante pesca por esos días, resultó ser una experiencia de vida que generó en mí la más pro funda admiración hacia este hombre, su oficio y el desarrollo de identidad local que veo reflejado en él.

Calar: Según me explica don Orlando, calar se le llama a la acción de extender la red en el mar cons truyendo una especie de gran muro fronterizo, que gracias a las boyas en la superficie y tensada por los pesos en la parte inferior, permiten cortar el paso a los peces que por allí nadan, quedando atrapados en la red. El tipo de red que se utiliza dependerá princi palmente del pez que se quiera atrapar; por ejemplo, una red de 6 ½ a 7 pulgadas sirve para reineta, una de 2 ¾ es para merluza común, de 6 pulgadas para corvina y una de 1 ¼ o 1 ½ permite pescar pejerrey.

Recorrer: Me explica que al otro día de calar la red viene el proceso de recorrer, donde se comienza lentamente desde un extremo del “muro fronterizo” subiendo poco a poco la red al bote. Seleccionando los peces que tengan el tamaño adecuado para el consumo y devolviendo los más pequeños al mar.

Le cuento a Don Orlando sobre mi residencia y me

encuentro con la sorpresa de que no sabe qué es Ca sapoli; sin embargo, luego de decirle donde está y como es, me cuenta que la ve en cada oportunidad que va mar adentro a calar la red.

Para la realización de este oficio, botes y embarcacio nes salen de la península a mar abierto para efectuar la pesca pasando inevitablemente por las faldas del acantilado desde donde emerge Casapoli. Todos los pescadores han visto este gran cubo de hormigón armado, sin embargo muy pocos saben de su vincu lación con el territorio.

Esta información y experiencia resulta ser el motor para el proyecto de intervención realizado y que gra cias a la ayuda de varias personas de esta comunidad se pudo llevar a cabo.

Resumen del Proyecto: Cuando las comunidades de un lugar desarrollan gran parte de sus vidas en torno a un oficio, vemos como la cadena humana se robustece y construye la zos socioculturales y políticas internas que dominan el quehacer cotidiano, por lo tanto, se hace común una forma de vida que - pese a las dificultades terri toriales - se regula bajo sus propias lógicas y modos de visión en cuanto al fortalecimiento de su identi dad local.

Por lo tanto, cobra fuerza el individuo colectivo, es decir, aquel que pese a trazar sus propios márgenes de autorregulación, lo hace también junto y para la comunidad a la cual pertenece.

Existen varios oficios presentes en la península, algu nos de ellos asociados a la agricultura, ganadería, avi

62

cultura y construcción por dar algunos ejemplos, pero la gran mayoría son cadenas de producción asociada al mar, así como los astilleros, remendadores de red, pesca en embarcación, pesca artesanal, recolectoras de algas, cultivo de mariscos, gastronomía, etc.

Si bien una parte de la investigación está centrada en cómo el hombre se relaciona con los instrumen tos tecnológicos que posibilitan la ejecución de sus oficios, el proyecto Calar- recorrer se levanta desde la experiencia de la pesca artesanal como un fenó meno que traza, proyecta, construye y visibiliza el aparente dominio del hombre sobre la naturaleza, pero un dominio que se basa en el respeto, la sen sibilidad y el entendimiento sobre el espacio natural en el cual se desarrolla.

un oficio arraigado en la identidad de la comunidad que aquí habita sobre un elemento arquitectónico que, según me comentan, no pertenece a ese terri torio. Siendo observado por los mismos pescadores como un volumen imponente que no reconocen como propio, mirándolo desde el mar con cierta ex trañeza y desconocimiento.

Pareciera ser que el hombre ha invadido todo el es pacio natural, tanto en lo geográfico como en la vida de otras especies pertenecientes al territorio, sin em bargo, lo que recibo desde la experiencia de la pesca artesanal con don Orlando es que aún se mantiene y cultiva un gran respeto por ese espacio natural mencionado. Me permite observar que lo que ha ge nerado el hombre - en este caso - para dominar su medio ambiente, es adaptar el entorno a si mismo, fabricando sus propios instrumentos de sobreviven cia y relación.

Calar - Recorrer es una intervención que plantea es tablecer esas relaciones, utilizando dos elementos que coexisten en el territorio y que representan ma neras de entender y vincularse con el lugar de for mas diferentes.

Es por eso que el proyecto se inicia calando Casapoli, para lo cual utilizo una red de reineta (7 pulgadas), ya que tiene 10 metros de alto 100 metros de ex tensión, lo que me permite cubrir por completo el volumen de Casapoli, intentando replicar de alguna manera el ritual enseñado por Don Orlando, donde desde un extremo se extiende la red, en este caso envolviendo la casa, para luego, al día siguiente, rea lizar el proceso de recorrer, ejecutando una especie de ceremonia de iniciación, vinculación y recono cimiento simbólico del gran cubo con la identidad local.

Ritual que, si bien es simbólico, conlleva una gran responsabilidad de vinculación y fortalecimiento de comunicaciones con todas las personas involucradas en la localidad de Coliumo.

El primero de ellos es Casapoli, que es el lugar desde donde yo como artista genero el acercamiento a la península, representando en este cruce, el elemento extranjero que de alguna manera se impone a la co munidad. El segundo es una red de pescar, elemento que simboliza el oficio que decidí tomar como refe rencia y que tensiona tanto material como sensorial mente la intervención realizada.

La metáfora que se realiza con el proyecto a partir de esta experiencia establece cruces y tensiones entre

Pág. 63

Calar, intervención con red de pesca sobre Casapoli. Registro Carla Motto.

Pág. 65

Recorrer, intervención con red de pesca sobre Casapoli. Registro Carla Motto.

64

LA ÚLTIMA BATALLA ENTRE LA FORMA Y LA LUZ

Victoria McReynolds | Arquitecta

Una lucha tiene lugar entre la forma y la luz cada vez que el sol se pone bajo el horizonte de la Tierra.

La predictibilidad y el carácter común de la puesta de sol aplanan los fugaces momentos combativos que siguen. Intenso por sólo una cuestión de minu tos, los últimos rayos de la luz se retiran y nuestros ojos pierden la definición de frontera y forma.

Con cada puesta de sol la luz golpea las nubes y cae sobre la tierra en un esfuerzo por alcanzar la forma antes de alcanzar nuestra vista. Y con cada anoche cer transformado en oscuridad, la forma se inclina al llamado de la sombra.

Nuestros ambientes oscuros difieren radicalmente de nuestros alrededores iluminados por el sol, determina dos por observaciones precisas. Es dentro de la transi ción crepuscular entre estos estados extremos de ilu minación donde surgen la sorpresa y la ambigüedad.

La certeza perceptiva del encierro se disuelve cuan do chocan los ángulos de luz que permiten la clari dad durante el encuentro de nuestra única fuente de luz natural bajando contra la cortina de luces eléctri cas que se elevan. Las paredes y los bordes se vuel ven inesperadamente pronunciados cuando la luz del sol cae horizontalmente, frotando las superficies, o cuando la luz eléctrica se adentra en las grietas. Es pacios adyacentes alineados al plan durante el día ya no están en alianza. Volúmenes a dúo que siguen la luz del sol se separan bajo el peso de la oscuridad y el aislamiento de una bombilla. Esta oscuridad inva sora reconecta vías perimetrales que estaban frag mentadas por el paso de la luz solar bajo el hilo de los haluros uniformes.

Incluso nuestro arreglo más racionalizado de deli neación ortogonal concreta cae preso a la reforma ción durante el crepúsculo, una y otra vez.

La última batalla entre la forma y la luz es un cuerpo de obra que investiga la fragmentación combativa de los límites formales durante el crepúsculo. Esta serie de dibujos, bocetos, fotografías y textos describen la disolución percibida y la reconfiguración de los volú menes y muros de Casapoli, entendidos específica mente durante el paso del día a la noche. Durante las dos semanas de residencia, el crepúsculo nocturno en el risco costero duró aproximadamente cincuenta minutos. En este momento, la diferenciación de los contenidos en primer plano y en el fondo chocan a medida que la luz del sol retrocede y la luz eléctrica afianza nuevos territorios. Este trabajo tiene como objetivo hacer visibles las etapas incrementales en tre luz y oscuridad. Como complemento al trabajo escrito y dibujado se encuentra la película Nadir, rea lizada en colaboración con el fotógrafo Xavier Tavera y el diseñador de iluminación Julio Escobar Mellado. En Nadir, la cadencia de batalla de la invasión de la oscuridad sobre la arquitectura se encuentra en pri mer plano contra el fondo de separación deslizante y conexión incierta. Esta última batalla entre la forma y la luz se observa a través de vacíos materiales y sobre varias superficies. Adicionalmente, estos trabajos so bre arquitectura, luz, performance y forma amplían preguntas previas respecto a la luz y la atmósfera investigadas en Light 110, un estudio de campo de siete meses realizado en 2015.

66 67

Pág. 67

Sketchbook. Registro Victoria McReynolds. Pág. 68

BattleFormLight: Nightfall Intimacy. Registro Victoria McReynolds. Pág. 69

BattleFormLight: Sky Sketch 07.07. Registro Victoria McReynolds.

68

69

RETRATOS

Xavier Tavera | Fotógrafo

El Proyecto Retrato en Casapoli examina la relación del paisaje con sus habitantes dentro de todo lo que abarca el campo visual, incluyendo todo el espacio expansivo desde una determinada ubicación geo gráfica. Investigué el paisaje como un espacio socioterritorial donde el paisaje natural se mezcla con el paisaje cultural, donde ambos se ven amenazados por cambios drásticos.

En Coliumo las prácticas artesanales de pesca, así como la recolección de productos del mar y la cons trucción de barcos de pesca, están amenazadas por la gentrificación y la reurbanización. La naturale za pintoresca de esta región es difícil de ignorar. El océano que rodea la bahía, los barcos amarillos y azules, las calles sin pavimentar, los días soleados, las tormentas, la luz que se refleja en el océano, el pes cador, los autobuses, los visitantes. Este pintoresco entorno se encuentra dentro de una ominosa ame naza justificada como aparente progreso en las gran jas de salmón, el gaseoducto y la pesca comercial.

Sabiendo de antemano que la fotografía es inútil para acceder a la realidad, hice una serie de retratos en colaboración con los residentes de Coliumo en un estilo clásico y pintoresco. El paisaje de Coliumo es un reflejo de sus habitantes y sus estilos de vida por lo que decidí documentar al pescador y a los traba jadores del océano dentro del paisaje. Mi propósito no era definir la identidad de Coliumo sino ir más allá de la noción de autenticidad representada en su identidad. Las imágenes idealizadas documentan las manifestaciones románticas de sus habitantes, pero no necesariamente la verdad. Las representaciones de los retratos sentimentalizan un tiempo y un lugar antes de que se convierta en un cambio drástico por

un futuro inevitable, haciendo de lo pintoresco un comentario político y un análisis político cultural.

Mi intención es que estas imágenes actúen como recuerdos de un lugar que solía existir, antes de que ocurran acciones drásticas de desplazamiento. Estos recuerdos están llenos de detalles visuales de los re sidentes de Coliumo y su geografía. Las fotografías idílicas crean recuerdos que se pueden recuperar con la ayuda de las imágenes. Los retratos pueden actuar como una reminiscencia de una historia con tada sobre un pasado y evocar un lugar que muchos esperamos recordar.

PROYECCIÓN DE VIDEO

La particular forma y ubicación de Casapoli me lle varon a filmar sus alrededores y proyectarlos direc tamente sobre su fachada. Una proyección sobre la estructura gris contra el océano azul y el cielo imi ta el paisaje y activa la presencia del edificio en un equilibrio aparente donde las proporciones y la es cala de la estructura imitan la magnitud del océano que se confunde con el paisaje.

Pág. 71

Jinete y caballo de carreras a la Chilena, Playa del Morro de Coliumo. Registro Xavier Tavera.

Pág. 72-73 Recolectores de algas en Punta de Talca, Coliumo. Registro Xavier Tavera.

70

71

Francisca Sánchez

Patricio Vogel

Sebastián Jatz

18 de julio al 18 de agosto 18 de julio al 18 de agosto 18 de julio al 18 de agosto

01234 O BREVE DESCRIPCIÓN SECUENCIAL HACIA LOS DIBUJOS MATERIALES

Francisca Sánchez | Artista Visual

0. DIBUJOS MATERIALES

Dibujos materiales es un taller experimental desa rrollado por Francisca Sánchez que busca establecer un diálogo entre escultura y arquitectura mediante ejercicios basados en la experiencia de dibujar exca vando espacios y túneles para usarlos como moldes de vaciado. En este taller participaron diez estudian tes de arquitectura de la Universidad del Bío-Bío, quienes durante tres días exploraron las posibilida des de la escultura en la arquitectura y viceversa.

1. EXCAVAR PARA HACER

Dibujar es la primera invitación, excavar la única restricción. Muchas veces el sentido háptico es com prendido como una dimensión menos precisa que el sentido de la visión y por lo tanto menos explorada para proyectar objetos. Contrariando este prejuicio, se les entrega a los participantes un bloque de es puma floral para que excaven túneles con sus dedos. Índice, anular, meñique, dedo medio y pulgar, de una y otra mano, buscan tocarse para confirmar que una red de túneles se ha tejido.

Lo siguiente es traspasar a papel lo que los dedos hicieron. Los croquis dan cuenta de búsquedas tan to intuitivas como racionales. Surgen los primeros cuestionamientos ¿Será correcta mi transcripción desde lo que hice y sentí con mis dedos, a lo que creo haber realizado mental y visualmente?

2. VACIAR PARA DEVELAR