Copyright © 2024 by LEVITATE literary magazine

All rights to the material in this journal revert back to individual contributor after LEVITATE publication.

LEVITATE Literary Magazine c/o Creative Writing Department

The Chicago High School for the Arts 2714 W. Augusta Blvd Chicago, IL 60622 www.levitatemagazine.org

ISBN 978-0-9995014-9-8

LEVITATE accepts electronic submissions and publishes annually. For submission guidelines, please consult our website.

Editors-in-Chief

Charlotte Hensley

Julissa Ortiz

Managing Editor Jenna Reasner

Lead Fiction Editors

Robin Barth

Nayeli Lopez

Lead Creative Nonfiction Editor Dayna Garcia-Ruiz

Lead Poetry Editors Shamiyah Hightower

Yamile Muñoz

Lead Themed Dossier Editor

Chaske Hunter

Lead Art Editor Adalys Cristobal

Contributing Fiction Editors

Contributing Creative Nonfiction Editors

Contributing Poetry Editors

Contributing Themed Dossier Editors

Contributing Art Editors

Lead Social Media Managers

Print Designers

Penelope Hammer

Allie Phillips

Kaden Washington

Charlotte Hensley

Noveli Lopez

Chaske Hunter

Julissa Ortiz

Maya Hernández

Karla Hernández

Adalys Cristobal

Mordekai DelGuidice

Noveli Lopez

Dayna Garcia-Ruiz

Julissa Ortiz

Karla Hernández

Mordekai DelGuidice

Kaden Washington

Maya Hernández

Noveli Lopez

Geoff Gaspord

Brian Brown

Trigger Warnings

Levitate Editorial Staff p.vi

Cover Art: Reach for the Stars Annika Connor p.8

Fiction

Boy Sepideh Saremi p.9

Master Artworks in COVID Times (visual art)

Cold Noodles

Alter Egos (visual art)

Filed and Forgotten

The Dance (visual art)

Yacht Rock 101

Groovin’ (visual art)

Creative Nonfiction

Donald Patten p.13

Sascha Matuszak p.16

Tomislav Šilipetar p.28

Katarina Behrmann p.30

Howie Good p.37

Langston Prince p.38

Howie Good p.49

Children’s Church (visual art) Christine Williams p.50

Something More

Two Hands

Neha Musuwathi p.51

A.D. Warrick p.55

A photo of Leo taken by the writer A.D. Warrick p.63

Burned Out

Marcela Torres p.64

the idle infatuation of idiosyncrasy (visual art)

Marie Magnetic p.68

what fascinates the masses (visual art)

Marie Magnetic p.69

Still Standing

Good Night (visual art)

My Uncle the Hummingbird

Kayla Blau p.70

Howie Good p.73

Rachel Paz Ruggera p.74

Cat and Butterflies (visual art) Zoe Nikolopoulou p.80

Black Cat (visual art)

Poetry

As Fall Begins 2 (visual art)

America’s Child

Zoe Nikolopoulou p.81

Edward Michael Supranowicz p.82

Emalie Anne Marquez p.83

when they plucked luna moths from my teeth

Afternoon Nap

somewhere in the light

Srishty Sharma p.84

Cami Rumble p.86

Adonis Alegre p.88

We fought about where to park but from here you could smell the sea and mist off the river at the same time (visual art)

Minuet (visual art)

Kay Heath p.89

Mark Hurtubise p.90

Solo Dance Betty Buchsbaum p.91

Daisies

Water Splash (visual art)

Untouched

The End of a Sonnet

Neal Donahue p.92

Yusif Zadeh p.93

Eric Blanchard p.94

James B. Nicola p.95

Seven Days of Forever Nikita Fishman p.96

The Doll-Maker’s Admission

Jha p.99

Love Tokens (visual art) Howie Good p.101

Sensitive

Learned Grief Audra Burwell p.104

You Betcha 2b (visual art)

Edward Michael Supranowicz p.106 apple knowledge Cordelia Hanemann p.107

To Myself at Twenty-Two, Driving Through Youngstown

Blake Lynch p.108

Head in the Clouds (visual art) Annika Connor p.109

Themed Dossier: Insomnia Shadows (visual art)

In the Belly of the Whale (poetry)

H. Felix p.112

Believer (visual art) Aleco Smith p.113

One-and-Twenty (poetry) Paul Hostovsky p.114

The Insomnia Sequences (poetry) Francesca Preston p.115

Requiem for an Undead Soul (fiction)

Anne Anthony p.119

Pieces of Looking Glass (visual art) Beth Horton p.122

Gothic (poetry) Sean Eaton p.123

Anterior Torso Musculature (visual art)

Donald Patten p.126

Eyes (visual art) Donald Patten p.127

persimmon souls at night (poetry) Sienna Morris p.128

The Moon Is Leaving Us (poetry) Christina H. Felix p.129

Galactic Lilies (visual art)

Carolyn Watson p.130

City on the Moon (fiction) Annabelle Taghinia p.131

Forget Me Not (visual art)

Jennifer S. Lange p.141

Trigger noun

A particular action, process, or situation that causes emotional distress and typically as a result causes traumatic feelings and memories to arise

Fiction

Boy forced/coerced underage marriage

Creative Nonfiction

Two Hands terminal illness, deathBurned Out depression, anxiety

Still Standing depression, anxiety, death of a child, school shooting

My Uncle the Hummingbird addiction, overdose, death

Poetry

somewhere in the light death

Seven Days of Forever terminal illness

The Doll-Maker’s Admission war, death

Spoiler sexual assault, suicidal ideation

Themed Dossier: Insomnia

The Insomnia Sequences abuse, depression, suicidal ideation, suicide

Gothic murder

Requiem for an Undead Soul death, abuse

City on the Moon forced/coerced underage marriage

Trigger warnings originated in psychiatric literature, notably about those who experienced post-traumatic reactions, for example “re-experiencing symptoms” such as intrusive thoughts and flashbacks due to sexual or physical trauma. Over time, the term has expanded to include potentially offensive or disturbing material.

We do not want our readers to feel uncomfortable without warning while reading. This page is to alert readers beforehand of triggering content and where in our publication it is found.

Healing begins with understanding. Thank you for reading.

–LEVITATE Editorial Team

Annika Connor

Annika Connor is a painter, SAG-AFTRA actor, and screenwriter whose creative endeavors are deeply intertwined. While she engages in multiple art forms, painting holds a special place as her primary passion. She finds that her experiences in acting and writing enrich her paintings, infusing them with narrative depth.

Connor’s insomnia has led to a unique creative process. Her vivid dreams inspire much of her work, with their imagery captured in detail upon waking. She keeps a notebook by her bed to immediately sketch or write, preserving the essence of her dreams before they fade.

In her paintings, Connor merges her love for storytelling with visual art, creating scenes that feel like stills from larger narratives. She uses visual metaphors and allegorical elements to invite viewers into a world where societal issues are subtly explored. Connor occasionally incorporates activism into her art, using it as a platform to advocate for social change.

Using traditional techniques with oils on linen, Connor’s paintings are intricate and rich, reflecting her meticulous process. Her work serves as a mirror to society, offering beauty and contemplation amidst the chaos of life. Through allegory and dream imagery, Connor’s art invites viewers to explore deeper into their own imagination and reflect on the world around them

Sepideh Saremi She had not thought she would have a boy, and her first thought when they placed him in her arms was, “I have birthed my own oppressor.”

And her second thought was, “I grew a penis inside my body.” She was lying on her back while the doctor sewed up the damage between her legs, and soon she would have to take this tiny future-man home. And she would have to name him, which was a problem because she’d really only picked names for girls, and the only Persian boy name she liked was also the name of his father, and that was not a Persian thing to do at all, to name a child after a parent, so she would have to defy her culture in that way.

The boy was very pretty, even with a smushed face and head elongated by her birth canal. He had a lot of thick black hair, and it curled against his scalp, matted down by her blood. He looked right at her with his enormous dark blue eyes, and she said to him without thinking, “I’m your mom,” and immediately heard the narcissism in it and felt ashamed. What she should have said was “You’re my baby,” which would have been far more gracious.

She turned to her mother and said, “I’m sorry for everything horrible I’ve ever said and done to you and for everything I will do in the future.” She felt an understanding and kinship with her mother for the first time, felt connected to her and to all of the women in their family who had come before them, and then felt sad that her son would never, ever feel this feeling, would never be on his back with his baby in his arms while someone sewed back together the most intimate part of his body, that he would never fully understand her, because he would be limited by his biology. And maybe this meant he would never be fully sorry for anything horrible he did to her, and she heard the narcissism in that, too, and again felt ashamed.

She thought about shame, and about how both of her grandmothers had never left their homeland except to visit grown children, had hardly left the cities in which they’d been born, and neither had ever learned to read, and here she was now, a modern, educated brown woman in the Western world who had just given birth to a blue-eyed white male.

It was astonishing that so much could change in just two generations, that her husband’s half-white genes and her relative fairness had conspired to create a phenotypical result that wiped out thousands of years of darker-skinned Middle Eastern ancestry, including her own olive-skinned mother who stood crying at the foot of the hospital bed and her even more olive-skinned father-in-law who would visit later that evening and kiss her hand and thank her for this little white boy, though to his credit her father-in-law was not a chauvinist with internalized racism and would have kissed her hand for a little brown girl too.

The boy was too quiet, and a phalanx of nurses came in and took him from her arms to neonatal intensive care, and she cried with fear. Then they turned right around and brought him back when he rallied in the hallway. She’d been a mother for fifteen minutes, and already he seemed to be doing better without her participation.

She thought about how both of her illiterate grandmothers had been married in their young teens to much older men, old enough that now it would be considered child abuse, and how all they had done was bear child after child after child after child until there were more children than anyone really knew what to do with, and the older children raised the younger ones. Each of her grandmothers had had babies who had died, and neither of them ever got over it, even after having half a dozen more babies after the ones they lost, and she could understand that for the first time.

She thought about conception and sex. What must it have been like for her grandmothers to have had sex for the first time when they themselves were still children, with men who were twice their age? Who prepared them for that and how? And had either of her grandmothers, in the course of all that sex for procreation, ever had a single orgasm? She wished she could ask them, imagining they might be relieved to talk about it, though this was a projection of her own Western, overly

therapized mind. Some things didn’t have to be talked about, couldn’t be, without causing great harm.

The baby was rooting on her chest, and she held him up to her breast, where he latched on and started to suck hard. Her breasts were massive now, with areolae that had turned nearly black in color and doubled in size. They were unrecognizable to her, mammalian artifacts, and she wondered if they would ever be tits again, but perhaps it would be better for them not to be, because the thought of anyone besides this baby putting his mouth on them made her skin crawl. She looked at her husband and felt repulsed and annoyed and angry.

She looked for the first time at the boy’s body. Someone had cleaned him up and loosely wrapped a blanket around him, but the front of him was naked and pressed against her torso. He looked like a long, skinny worm with big thumbs, and he took his mouth off one breast and mewled for the other one, and her heart broke for him.

She thought about all the times that she had let someone put his mouth or hands on her body even though her skin had been crawling, and the magic trick she had learned when she was just a few years older than this boy, the floating out of herself until whatever was happening stopped. She had gotten so good at this that she wasn’t really able to stay put anymore, even if she wanted to be touched, and as a result there were blanks where memory should have been. She wondered if either of her grandmothers had learned this trick when they were being touched for the first time, how scared they must have been, and wondered if they had eventually learned to stay put.

It wasn’t all bad, of course, as she’d used the same trick while the boy had been slowly leaving her body over the last day and change. There were contractions, people in and out of the room, then poof, she was gone, the rest was blank. Now here was a baby, and here were some stitches, which the doctor had finished sewing, she realized.

She could feel the boy’s heart pumping against her chest. The months he had been inside her body, she had felt hollow, felt like part of her had been carved out and discarded in order to make room for him, and it made her feel broken and depressed. But she could feel the edges of something else inside her now, some other grief filling the space he had just vacated, something ancient and extremely sad, the grief of every mother who preceded her.

She started crying again and didn’t know why, and it would take her months to realize it was because she did not know how to love anyone fully, and that her inability to let anyone love her fully meant she would push away her own child. That this would break his tender heart, and very early he would have to sit alone in rage and despair, in the same ways she’d had to, unless she could find a way to stay in her body, stay with herself, and stay with him too.

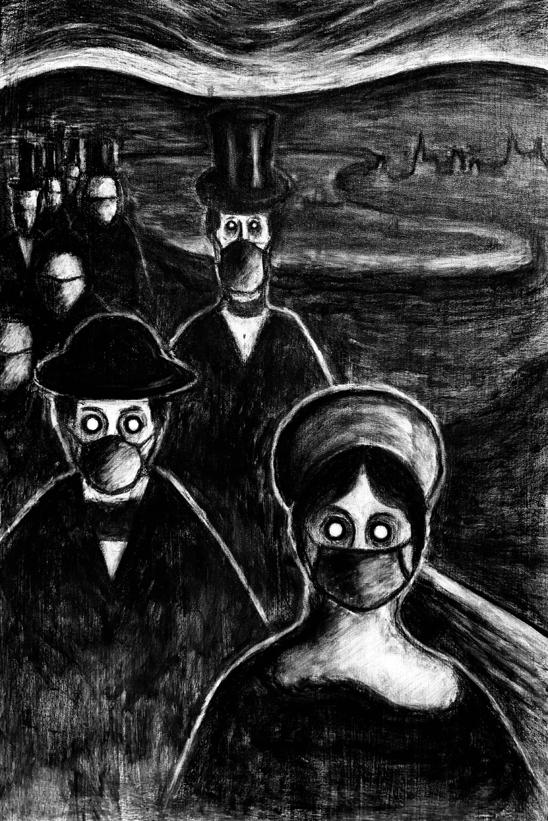

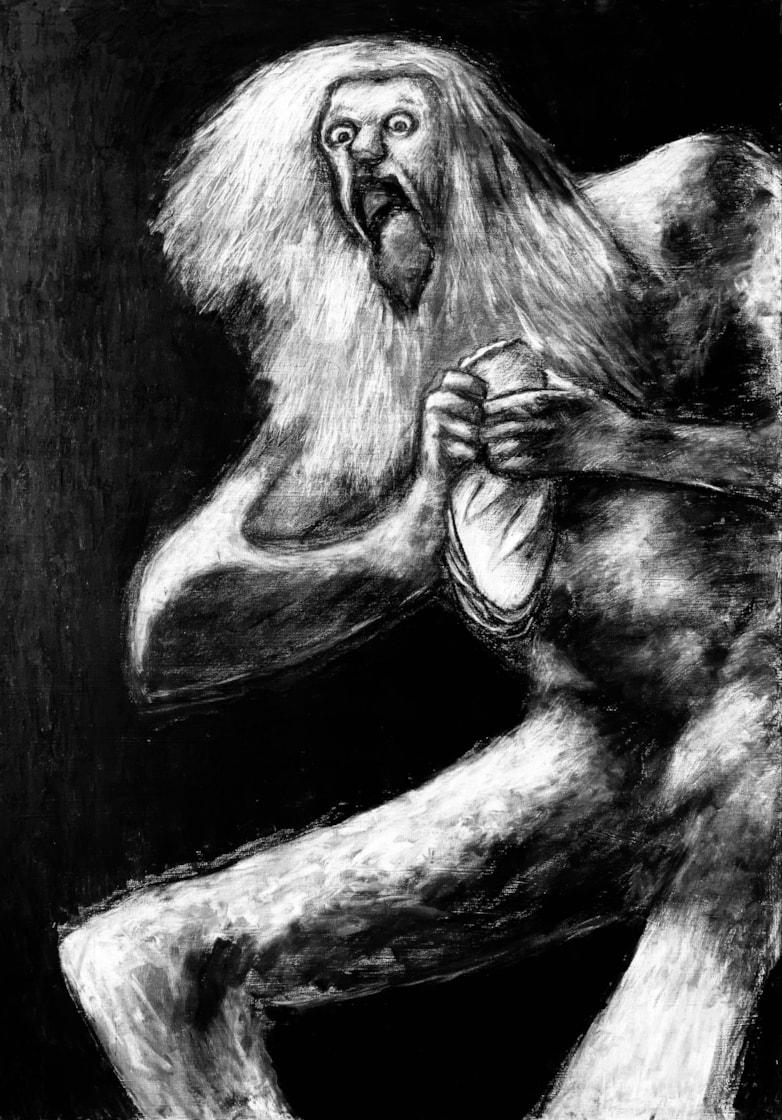

Master Artworks in COVID Times (a series by Donald Patten)

Donald

PattenAlmost overnight, COVID-19 changed the way people interact with each other and with our own bodies. We live our lives in vulnerability during this historically significant time of disaster. The initial phases of the pandemic are behind us, but the virus remains and continues to be dangerous. The societal trauma this pandemic has caused will be remembered and felt by those who lived through it for the foreseeable future. In the past, master painters would depict historically significant disasters that happened to them as a way to cope. Artists of the nineteenth century depicted hardships and trauma in the wake of the Industrial Revolution that began the formation of our modern world. As an artist who is learning the techniques of masters, I have the opportunity to create long-lasting visual information that depicts the trauma of this pandemic. This series of drawings represents my experiences in COVID by revising past masterpieces to depict this embodied experience of trauma.

Café Terrace at COVID Capacity

Saturn Devouring His Sub charcoal

As long as he had been alive, Liu Peng had never witnessed a sky as clear as this one. On this most rare of days, during the last moments of the pear blossoms and the first breath of the rosebuds, he could see the Longmen Mountains in the distance. The smog and the haze that normally obscured them had been whisked away by the earthquake. His heart trembled, given the circumstances. This strange weather felt like a vast moment of silence for the dead and buried, a moment for the land to process what had just happened. There were new cracks to explore, rivers that followed new courses, and barely settled scapes where once there’d been homes.

The silence was more profoundly unnerving than anything he had ever experienced. Not as painful as heartbreak nor as consuming as jealousy nor as heavy as school—but so much stranger, as if all the worlds seen and unseen gathered to stand quietly witnessing. No honking from the highways, no cranes, no dump trucks, not even a motorcycle. The entire modern world had shimmered and vanished. There was only the wind. Even the birds perched silently, cocking their heads at the bright sun, as surprised to see it shine through clear skies as any other living thing in Chengdu. The city was encased in a sunny bubble of quiet aftermath, shocked and wide-eyed. It made it easy to pretend everything was okay, even though nothing was.

The news called the quake the most devastating calamity to hit China since the Japanese. The epicenter was two hours northwest of Chengdu, but they had felt it rumble in Beijing, in Tokyo, and in Bangkok. In the village of Ten Thousand Fortunes Unit Four, aftershocks shook them awake at night, and his mother swore she could still feel the earth move long after they subsided. Liu Peng’s joints ached, his calf muscles twitched as if small beasts fought beneath his skin, and he dreamed strange dreams of thick liquids poured down onto fleeing stick things.

On his most recent trip north with the relief crews, Liu Peng had seen valleys filled in with rocks and shattered roof beams. Bits of home

life stuck up from the tossed earth, fluttering flags of tattered clothes and ripped curtains. In the towns between Chengdu and the epicenter, bulldozers rummaged through concrete and rebar while Liu Peng and his classmates scrambled across rubble with volunteer construction workers shipped in from Guangdong. In Huawang, they looked for survivors, but all they found was more sad fabric and the smell of death, and the clock tower in the center of town frozen at 2:28 p.m., May 12, 2008. The quake had measured 8.0, and the Party had announced a death toll of 80,000 people. The symmetry of all those eights appealed to Liu Peng. It lent a thin layer of meaning to what seemed entirely incomprehensible. Boxed in nicely, it could be endured.

Liu Peng hadn’t slept much in the last two days. After arriving back at Unit Four just before dawn, he had gone down to his aunt’s convenience stand to sit with his mother and trade news and rumors with the rest of the clan. The sun rose like a halo behind Great-Uncle Zhuang as he reminded everyone that the earthquake had struck the day after Buddha’s birthday, which he interpreted as calling for the Chinese people to endure this catastrophe as sublimely as only the Chinese could. Later, as Liu Peng’s aunt served a breakfast of porridge and fried dough, Douzi’s grandfather marveled aloud at how he could see the Longmen Mountains from his window again, like when he was a kid. His words had stayed with Liu Peng, and he found himself distracted by the view, even as Douzi told him she was leaving for good this time.

A breeze swept across him and Douzi as she played with the grass between them. He felt brittle and easily swept away, like the dying blades she held in her palm. They sat in the hollow by the dead well, at the corner of three fields, bathing in late morning sunshine. She had on a white T-shirt that barely covered her navel and blue jeans that tapered down to sockless ankles and drab white tennis shoes. He had tried to get her to wear contacts, but she insisted on the black wire-rim glasses she said made her look smart. She still wore the frayed cord around her neck that he had bought in the city, and he watched it bounce gently against her collarbone as she spread grass between her fingers, letting it fall on a beetle making its way determinedly over the pile she had made. There really was not much to say, so he smiled and pretended to pull grass blades too. Another gust of wind bent the grass into new shapes as

a wispy white cloud drifted across the perfectly blue sky. He just wanted to stay here, with the sun on his face, in this forever moment, this forever vein, and so he stayed quiet and tried not to breathe too loud.

She turned her hand over, and he saw the little white scars on her knuckles from chopping vegetables. They had both been raised by brown-skinned peasant parents with calloused peasant hands, but Douzi had meticulously maintained her fair skin, while Liu Peng’s hands had gone soft in his years at the university. He had student’s hands now, and he wore student’s clothes. His dark blue pants were clean and pressed, and the sleeves of his white button-down were rolled up to his elbows. Still impossible to escape our peasant heritage, he thought, staring glumly at the scars on her knuckles and the thin layer of caked red dust around the toes of his black dress shoes. But they were trying.

An official letter from the local Party Secretary fluttered in his hand. It had arrived while Liu Peng was in the earthquake zone with his classmates, searching for bodies. The local government was reclaiming Ten Thousand Fortunes Unit Four for developers, the letter stated, and every family had to sign over their land in order to receive compensation. Furthermore, the letter continued, compensation would be doled out in payments over time, culminating in an apartment in the high-rise that would eventually replace the village. In the meantime, everyone in the village would have to find someplace temporary to live.

Her family had made a decision, Douzi was saying. They were moving across the province, to Chongqing, where they had relatives. Chongqing was a good twelve hours away by bus. It wasn’t that far, she was saying, but to Liu Peng it felt like the end of the known world.

“Never mind,” Douzi said, changing the subject. “Are you going to head back into the crisis zone to meet back up with the class? Or will you stay here all week?”

Liu Peng watched a tabby disappear behind a whitewashed farmhouse wall, then turned to watch a solitary old man dump water into the brown ruts of his fields. The sun beat down upon the back of Liu Peng’s neck, and he wished he had a nice wet towel like the old man’s to wipe away the sweat.

“If you come back with me, I’ll go,” he replied.

“Ah Peng,” she said, raising her eyes to his. “I can’t go back up, and you know that. We’re packing all week and then leaving on Sunday.”

“Then I’ll stay here with you.”

She was silent for a moment.

“I want to spend these days with you, too, but if I weren’t packing my entire family’s belongings into a truck this week, I would be out there,” she said, pointing vaguely north. “They need you out there. Staying here for me is just…silly, especially with so many more important things going on.”

“You’re right,” he nodded. “You’re absolutely right.”

“Of course I am,” she said with finality.

Liu Peng kept nodding, unable to think, let alone speak.

He remembered the electric shock that had swept through his body after Douzi had texted him the news about the letter and the developers and how her mother wanted to move to Chongqing. He and his classmates were staying in a village headman’s hut outside of the epicenter. The headman had slaughtered a pig for them, and they had eaten around a campfire, giddy with collective purpose and patriotic pride. He had just stepped away to call her and tell her about his day when her name flashed across his phone.

Sweating, dizzy, he had done the only thing there was to do: take what money he had and pay the headman’s son to drive him all the way back home that very night. His classmates called him a fool, but nothing could have stopped him. As soon as they set off, Liu Peng started telling the headman’s son everything, breathlessly, as if he could talk away the fever in his head and break the iron bands constricting his chest through sheer force of confession.

He told him about the first time he’d noticed Douzi, the pretty girl in the back answering a tough question in English class, and how he waited for her to break up with her first boyfriend, and those spring days back in ‘05, wooing her in Dujiangyan on the South Bridge above the rushing Min. He told him about drifting like a ghost through an entire year of school while she experimented with that older boy whose name still made him shudder, and how now her family was moving to Chongqing and this was his last chance to tell her how much he loved her and to finally ask her to marry him. The headman’s son barreled over the potholed roads, lighting his cigarette with the burning end of the last one, honking furiously at anything that crossed their path.

“We’ll get you there, brother,” he had promised. “And when you

two get married, I’ll come drink with you.”

Liu Peng then spoke of those first weeks after the earthquake, sitting in the back of a pickup with Douzi as she scanned the broken land, her jet black hair flowing in the wind. He wondered aloud if those early summer days in the hills around the epicenter would be the best days of his life.

“Your best days are ahead of you, brother,” the headman’s son had shouted. “Take heart!”

For as long as he lived, Liu Peng would never forget that wild ride, nor the headman’s son and his wild eyes, his cigarettes glowing fervently in the night as he swore to come visit when Liu Peng married Douzi.

Sitting on the hill by the dead well and playing with grass, the sun burning his face, Liu Peng remembered when he’d first asked Douzi to come with him and his classmates into the crisis zone and head north from Chengdu all the way to the epicenter in Wenchuan. To look upon the broken dam and see into the center of the earth with him. But she had insisted on staying home with her mother. Liu Peng imagined he’d see Douzi in every town. He looked for her around corners, on buses, and in relief groups just like his. But it was never her, only some other girl with a ponytail, wearing glasses and washed-out jeans. His throat swelled with sick regret for wasting that time, all that precious time he could have spent with her, all that time gone forever. He should have stayed here, in his village, with Douzi and his mother. He should have been the one to receive the Party Secretary’s letter.

He gazed down upon the characters on the page. He turned the letter on its side to see if some other message dropped out. The government had given every family till the end of August to sign over their homes and move out. Not even three months. Liu Peng still couldn’t quite believe it was happening, but he had done the math. Unit Four had sixty-six days left on this earth. If he thought of it as six million seconds, it felt much further away.

The thought brought to mind the long-winded speech Professor Chen had given on the last day of class before the earthquake struck. From moment to moment, the physics professor had said, systems move from one state to the next, each state giving rise to one of several new states, each with some new probability.

“But all the real action of the world occurs at the bottom level,” Professor Chen had declared.

At the bottom level, Liu Peng thought. Is that me?

Douzi stood up and brushed herself off.

“Come on,” she said. “I have to help my mom with lunch.”

She reached down to take his hand. He rose and they began walking back toward her house. Liu Peng was suddenly struck by how many times he and Douzi had strolled just like this, holding hands, down to get noodles by the bus stop into the city. He straddled all those times, all those iterations of him and the girl he loved, and through this forever time felt a coherent thought emerge through the hard lump in his throat.

“Hey,” he croaked, startling her. “Let’s get some of those cold noodles by the bridge.”

“Oh my God, that’s a great idea,” she cried, clapping her hands beneath her chin. “I love those noodles!”

They took the small dirt path down the hill through the bamboo grove, the one that went behind all of the houses, the one the cats used. Remember this, commanded a voice in his head, remember all of this. Liu Peng felt himself slip away into the embrace of no-time and no-place, before the quake and before the letter, into a fantasy of him and Douzi running behind the houses again, hand in hand like always.

The path turned to hug the house his cousin lived in. Douzi trailed her finger along the chipped white paint of the wall. Liu Peng watched her do it and did the same, feeling the soft sharp edges crumble at his light touch and fall below to join countless other white shards in the mud. He made sure to watch the mud form to their shoes and listen for the wet sound their soles made when they fought free. Lightheaded, he took care not to stumble and slip.

They left the shaded bamboo grove and stepped out onto the sunbaked pavement, walking slowly past the last house of Unit Four, Auntie Meng’s house. Popo, the dirty Pekinese who guarded this stretch of the path, the one with the massive underbite, yawned at them as one of her mutt puppies barked madly on its chain. Little Yaoyao’s toys littered the courtyard, and Liu Peng saw baskets of bean sprouts sinking into each other on either side of Auntie Meng’s doorway. Her television was on, and Liu Peng caught a flash of it through the open

door. An official with his sleeves rolled up was speaking to a reporter.

“We are striving together…” he was saying, but Liu Peng couldn’t catch what he said next.

The cracked pavement ran out the back of the village, between two mostly fallow fields filled with stacks of bricks and garbage and all the aunties’ side-gardens. The creek at the far end of these two fields marked the border between the twelve families of Unit Four and the nine families of Unit Seven. There was a bus stop at the border that went into the city, and that’s where the noodles were. It felt natural to pause at the threshold of the two fallow fields, just past Auntie Meng’s house, and wait for the breeze to cool them down a bit. Liu Peng released his hand from Douzi’s, wiped it dry on his pants, then took up her hand again, interlacing his fingers with hers.

In the field to their left, two rows of chives lay limp in newly dampened dirt, waiting to come back to life again. In a corner of the field to the right, a row of cabbage heads stretched out in the heat. Weeds grew wild along the pavement, jostling roughly with dead brown stalks and blooming rapeseed. Green vines snaked between the diamonds of a sagging fence, slowly strangling stray pieces of red and blue plastic. Beside him stood Douzi, smiling and gently swinging her hand in his. Another of his aunts, Auntie Pu, the one who had moved across the lotus pond, was pulling weeds from the cabbage row. Behind her, on the far side of a stone retainer wall, Liu Peng could see the ruins of a restaurant built beside the fields but never opened. She straightened, one hand on her hip, and called out to them.

“Where are you two going?”

“Hi Auntie Pu,” Douzi’s voice rang out. “We’re going to get a bowl of noodles!”

“Ah,” Auntie Pu grunted in reply. She turned back to her work.

“Are those bean sprouts behind those cabbages?” Douzi asked.

“Yep,” Auntie said, shielding her eyes from the sun. “If we don’t grab ‘em now, they’ll get hard and bitter.”

She eyed the two young people up.

“Douzi,” she said. “I heard your mom made a decision.”

“She did,” Douzi answered. “We’re moving to Chongqing to be closer to my Gramma.”

“Chongqing,” Auntie exclaimed. “Well then what are you two

going to do?”

“We’ll be fine,” Douzi said, squeezing Liu Peng’s hand. “Ah Peng will come and visit!”

“It’s so far…” Auntie Pu said, her voice trailing off.

Liu Peng almost staggered across the field to fall into Auntie Pu’s rough brown arms and sob, but Douzi tugged on his hand and pulled him along the path.

“Well, see you later, Auntie,” she said. “Off to get noodles!”

They reached the tiny footbridge at the end of the open path, where ten thousand mosquitoes hovered and buzzed. They ducked their heads and ran across, swatting at the mosquitoes and laughing. Liu Peng, surprised he could still laugh, looked down and saw the creek water was neon blue. He knew it came from some chemical factory upstream, but he had never figured out what exactly was happening there. Every so often the water just turned bright blue for a day.

“Hey,” he said, letting go of her hand. “Let me take a picture of you by the bridge.”

“By the blue water?” she asked, frowning.

“Yeah, it looks neat,” he said, pulling out his cell phone and flipping it open.

“I mean…it’s pollution, Ah Peng.”

“Whatever.” He held the phone up and framed her face in the blurry square.“Just smile.”

“Fine.”

Douzi grinned and flashed a peace sign. They both huddled around the phone and inspected the photo.

“The background is completely white,” Douzi said.

“Yeah, but you can see your face pretty clearly.”

“No, you can’t.”

“I mean, I know it’s you,” Liu Peng said.

“Yeah, but will you be able to say that in five years?” she retorted.

Liu Peng looked down at the picture on his phone.

“I should think so,” he muttered.

Douzi pulled him along, past the neon creek and onto the blacktop road. City folk were waiting at the bus stop beside bags of locally bought flowers, fanning themselves and checking their watches. The noodle shop was just ahead. Two men sat at a table there, each digging

into the steaming bowl in front of them. Sister Du noticed them coming down the street. She waved and turned back into the kitchen.

The powerful glare of the sun turned the shadows as sharp as knives. All thoughts burned away, and Liu Peng could think only of how to get beneath an umbrella at one of those tables. Yet even as they scuttled across the softening blacktop, Liu Peng reminded himself that this was part of the memory. Remember this heat, it will help bring it all back. Remember how slippery her hand was as she slipped away into her seat on the street side of the table.

Sister Du brought them two cups of tea and a plate of boiled peanuts, and they ordered two bowls of cold noodles. Douzi took a sip of her tea and unsheathed her chopsticks.

“How’s your mom?” she asked, snatching up a peanut.

What could he say about his mother that wouldn’t have him collapse even further into despair? Should he tell Douzi how his mother beat her chest in anguish and cried by their door every night? How she made Liu Peng memorize their family tree all the way back to the first Hakka clans who migrated here more than five hundred years ago? How his parents fretted over the fate of their ancestors’ graves behind the lotus pond? His father tried to keep their spirits up with stories about Liu family ancestors who had been scattered to the winds before, only to find a home again, and he reassured the family they’d do the same. We won’t be cut off from our roots, his father promised, because our roots extend to everywhere in Sichuan, we Hakka can survive anywhere. But I don’t want to survive anywhere, his mother cried, I want to die here. And to that Liu Peng and his father could only hang their heads in shame.

“She’s not good,” he managed.

“Has she made a decision about where to move yet?”

“Not yet,” Liu Peng admitted. “They’re thinking of Longcuan, but maybe Luodai. Depends on work, really.”

“Well, I hope they choose Longcuan,” Douzi said. “That way at least they’ll be closer to you. You’re still going to Sichuan University, right?”

“Yeah,” Liu Peng said. “How about you, are you still…”

“Of course not, silly,” she cut him off. “I’ll probably head to Chongqing Normal, or maybe the Teachers’ College.”

Chongqing Normal had a nationwide reputation for having pretty girls with low test scores. They said BMWs hung out by every gate, waiting to pick them up. Liu Peng couldn’t bear to think about it. He felt gas building up in his belly.

The noodles arrived. They were thickly cut and covered in sweet red sauce, green onions, and peanuts. Liu Peng hesitated before mixing the bowl; it looked like a painting he didn’t want to destroy. Douzi was already digging in, methodically covering the noodles in sauce and digging up chunks of meat and flavor from the bottom of the bowl.

“I saw your mother crying by the door the other day,” Douzi said through a mouthful of noodles.

Liu Peng nodded.

“Your family’s been here forever.”

“A bunch of generations,” he shrugged. “The Lius were one of the first Hakka clans to leave Fujian and travel to Sichuan. There’s Lius all over Sichuan.”

“All over China, you mean.”

They both snickered. He felt her gaze on him as he slurped noodles.

“Ah Peng,” she finally exclaimed. “You’re so quiet about it all! Doesn’t it bother you that your home is about to be torn down, that your mother sobs in her yard, and your ancestors are going to be crushed by twenty stories of concrete? You never have anything to say!”

“I’m here, aren’t I?” he shot back.

“What’s that supposed to mean? And besides, you came back for me, not for them!”

“I came back for you both!”

Douzi rolled her eyes, grinding Liu Peng’s already broken heart into dust.

“I just wish you’d get angry about something,” she whispered. “Show some passion. You’re so even-keeled all the time, it drives me nuts.”

“Douzi,” he said, in the quiet voice before the tears. “If anyone is nonchalant here it is you. Don’t play dumb. If you move to Chongqing, the most we can expect is a visit or two before you break up with me—” he spoke over her when she went to interrupt him— “If you think none of this bothers me, then you must not know me at all, even

after all these years. Everything about this bothers me. The devastation up north, all the dead bodies, the Party just wiping our home off the map without thinking, my mother unable to eat, my dad out of a job…you…you laughing and happy and pretending like Chongqing is a solution. Pretending like you don’t know the only thing in the world I can think about is you.”

Liu Peng was shaking. Douzi looked down at her bowl. In the silence, Liu Peng’s mind wandered. He saw mahjong tables by the village store, lit up from above by a single light bulb. He saw his mother talking quietly with one of his aunties. His father playing cards and smoking; shirtless Uncle Liu telling everyone who would listen about the cigarette factory and how little they paid. He saw the grannies in the fields with their granddaughters, pouring water onto the roses. Another Uncle Liu, the rose farmer, laughing and showing missing teeth and smelling of rice wine. He heard skinny village dogs baying at a stranger in the middle of the night and the nasally whine of the cabbage-hawker as he rumbled through the village on his open-faced tractor at dawn. And at every turn Douzi, just ahead of him, looking back and smiling.

“I want to marry you,” he whispered. “I want you to marry me.”

“Stop it,” Douzi said quickly. “I love you Ah Peng, I really do, but I don’t want to get married right now. I already told you that. I don’t want to stay here in this village and be somebody’s wife. That’s not for me.”

“But I’m going to Chengdu,” he whispered. “And I’ll get rich for you. I promise.”

She reached across the table to touch his hand. Liu Peng looked at their fingers entwined, his brown and soft, hers thin and white.

“Ah Peng, come visit me in Chongqing, okay? Every chance you get.” She locked eyes with him. “I’ll come visit you, too. I promise!”

“Sure, until you...”

“Until I what?”

“I mean…” he stuttered. “Until you…”

“Until I meet a rich man who drives a BMW and I marry him and never speak to you again? Stop being an idiot. We grew up together, Ah Peng, and I love you. I have no idea what the future holds, but I do know that you will always be in my life. Just because the whole world is falling apart doesn’t mean we have to fall apart too.”

Douzi irritably brushed her hair out of her eyes.

“You better come visit me for the National Day holiday,” she said. “Or I’ll never speak to you again.”

She imperiously stuffed a wad of noodles into her mouth and slurped. The end of one noodle shot up and hit her in the face. She hissed and wiped her face with a napkin. There was still one red spot on her nose, and another on the lens of her glasses.

“Stop gawking at me and eat,” she cried with her mouth still full.

Liu Peng nodded obediently, swirled the noodles into a dripping red ball, and then shoved them into his mouth. He grunted in approval at the sweet meaty goodness and the satisfying crunch of peanuts and green onions.

Douzi washed down her noodles with a gulp of tea.

The men at the other table lit up cigarettes.

A village dog barked madly in the distance.

The sun reached beneath the umbrella to tickle the back of his neck again. Above him a cloud swirled, a lazy breeze blew, and the two of them slurped and smacked their lips. Time stuttered, and Liu Peng felt a forever moment pass, and then another.

And another.

Patrick was a curious boy in both meanings of the word—inquisitive and strange. At the age of newly walking and talking he followed a rabbit well past their property line toward the marshy area that adjoined his parents’ land. He wanted to see where this rabbit lived, how it lived, and who it lived with. It wasn’t until he heard his mother’s desperate screams for him that he realized he had gone too far. This curiosity would continue to duel itself as his greatest characteristic and the one which most endangered him.

Others around Patrick always took note of this strange absentminded behavior. A boy who wanted to know everything so sincerely but would only walk away with pieces of the stories he sought after. Persisting in knowing each detail of the bedtime stories he was read at night, he would wake up the next morning missing an intricate detail. Little Red Riding Hood’s grandmother ceased to exist in his recall of the classic. Or asking strange questions like who is Gretel? As if there was ever a time that you would hear about a Hansel without a Gretel. And Cinderella in his mind never made it to the ball. She was still in her own little corner, in her own little chair. It wasn’t like he rewrote the stories he was told. There were just chunks of them missing.

Sleep visited Patrick night after night, and that’s when the real work started. The clerks in his brain awoke as he lay dreaming. It was time for them to clock in for their shifts. So they could begin filing his memories.

You see, there are three categories memories go under: Short and long term are the most well-known. But there is one category, a sorting place that mirrors its name, spoken of with an indistinguishable fear that can’t be easily identified. This place is known as The Forgotten. Files that fall into this ill fate are wiped clean to create space for new memories. This isn’t voluntary—it is necessary. Perhaps it would be last Tuesday’s breakfast or your childhood neighbor’s dog. None of that would matter because once it was moved into The Forgotten, it was gone.

Unfortunately for Patrick’s case, he had one too many clerks assigned to his brain. A gross oversight by the foreman in charge. The foreman was new to the job and it was his first time assigning clerks to a brain. His assignment was simple: the average human has exactly 486 clerks operating in their head. Therefore each of the memory departments should employ 162 clerks. However, The Forgotten department in Patrick’s head had 163. This inaccuracy would cause more and more of these memories to disappear. Core memories that weren’t supposed to disappear.

These memory lapses became more apparent during grade school. A teacher explained that Patrick had come to class every day this week asking the same question. She dismissed it at first, thinking it was some sort of joke due to the hushed giggles and sneers of his classmates. But the musing of the other students soon faded into unsettlement, and with Patrick’s curious eyes still looking to be answered by her, she realized this wasn’t a practical joke. He truly wanted to know if mammals could breathe underwater for the eleventh time.

In those adolescent years, doctors seemed to think Patrick had a learning disability that was hindering him from retaining information. They weren’t wrong. This extra filing clerk was hindering him from learning. But no matter what medication they prescribed, it never seemed to fix these lapses.

It wasn’t until high school that those closest to Patrick realized something more was going on with his brain. Claire, the girl who shared her lunch with Patrick in the fourth grade when he forgot his, was a longtime companion. Truly his only companion. She didn’t mind his forgetfulness because he was kind. Claire was bullied for too many reasons. Reasons that truly shouldn’t matter unless you were a bunch of insecure grade schoolers. But with Patrick, he was sweet even when he was being teased. Almost like his curiosity wanted to understand the jokes that were being made about him so sincerely that he wasn’t even hurt by them. They easily became a pair and throughout the years were inseparable.

It was Claire who first noticed the extent of the wide array of missing information that seemed to be disappearing. She began documenting it in a small purple journal, with a list titled Things Patches Forgot. One unremarkable lunch period during year nine, they were

sprawled out at their usual spot, a bench outside the old auditorium. That was when she noticed something truly unusual.

The two of them were both fans of superheroes, and they had created a few characters of their own that they would bring to life in hand-drawn comics.

“Oh! I know, then Professor Thalmor can call a ‘meeting of the minds,’ that’s how we can get them all to the museum!” Claire explained while sitting on the ground in front of the bench, hunched over a drawing.

“Yeah! I like that! But who’s Professor Thalmor?” Patrick asked. Claire’s head snapped up; she had been gauging that inquisitive face for years. It was pure, like a spark deep in his eyes. He really just wanted to know. It was at that moment Claire knew this wasn’t one of the countless doctors’ diagnoses that Patrick had received. It couldn’t be. It wasn’t about his ability to comprehend. It was his memories! Professor Thalmor was the first superhero they had ever created. It was Patrick’s superhero, hands down his favorite! He wrote a fourpage origin story for him in sixth grade. He created him, and now he no longer recognized him. This wasn’t the first long-term memory to get accidentally placed into The Forgotten. But it was the first time someone noticed.

Now, one wouldn’t think having an extra filing clerk in your brain would be such a big deal. After all, we have hundreds. The memories that are sorted into The Forgotten are very meticulously chosen by your foreman. So as each clerk clocks in for their shift, they press the release button for the file they are sorting. But every night the clerk who doesn’t belong presses the release button, and the foreman, not having prepared for this oversight, chooses a memory at random. One extra memory a night, 365 days a year for Patrick’s life thus far… Well, let’s just say he was accumulating massive amounts of missing information. Information that could be relearned during waking hours, but as soon as his eyes gave into that night’s sleep, they would be wiped clean again. By year eleven, Claire had documented enough evidence that she decided to present it to Patrick’s parents. She had categorized memories that would be considered short and long-term. Also noting the dates that he had known something that seemed to be gone now.

Patrick’s parents were a bit unsure how to digest this precocious

teenage girl presenting her graphs and data in their living room. Nevertheless, they were grateful to have someone in their son’s life who cared so greatly for him. They agreed that perhaps it wasn’t an issue with him retaining or learning new information but rather him forgetting it.

The rest of the school year’s weekends were spent with Patrick in and out of doctors’ offices and clinics performing various tests and studies. Claire would often tag along, and she continued to track Patrick’s lost memories. One weekend they kept him overnight to track his sleeping patterns. The results were inconclusive. Although there was a little extra brain stimulation during his REM cycle of sleep, it wasn’t significant enough to be considered abnormal.

This meddling of his mind also seemed to be taking a toll on Patrick. That curiosity that was so endeared by Claire and others seemed to be putting him in dangerous situations. First was the countless money he would give away to a man outside the corner store. It was easy to take advantage of him in this way, with phrases as simple as “You promised me yesterday you would…or don’t you remember?” Patrick was so used to being told he had forgotten something he wouldn’t even bother to question.

More serious situations would include him losing his way home from the movies, leaving the stove on at home, and getting in a car with a group of strangers.

By graduation, the doctors had ruled out everything from amnesia to early-onset dementia and so much in between. It was a bittersweet walk across the stage as Claire collected her diploma. Looking up to the crowd to see Patrick cheering loudly for her, rather than sitting with the rest of the class below. And by the end of summer, Claire was packing for college as Patrick’s family had decided he wouldn’t be returning to repeat his senior year and that homeschooling would be a better option.

The two friends sat on a familiar swing set found in the park equal distance between their houses. The early August air dampened their skin while they lazily rocked back and forth.

“I think it has something to do with when you’re asleep. Like, I’ve seen a direct correlation between knowing one day and then the very next it’s gone,” Claire said, thinking out loud.

“Yeah maybe, who knows,” Patrick agreed.

“Do you want to stay over this weekend? I figured we could conduct our own study.” She looked at Patrick, already knowing his answer would be yes.

That weekend Claire had big plans. The first being no sleep. They would stay up for forty-eight hours straight. She would track to see if there were any missing memories throughout those two days. Furthermore, she would revisit things that he had forgotten and reteach him about those memories. For example, Professor Thalmor, their very own superhero. She spent the whole first day revisiting that character with him. Also, other big things that had seemed to have gone missing over the years. Every ten hours she would bring up the Professor and a few other random things they had gone over to see if he remembered them. And he did! His knowledge of them only dated back to Friday evening when he first came over for the “no sleep” over. But they were intact—all weekend! Sunday night they said goodbye, completely burnt out from caffeine-induced insomnia.

The clerks in Patrick’s brain stood uneasy that weekend. They had never gone forty-eight hours without work. As they all stood, files in hand, waiting for their shift to start, the foreman noticed something odd. With equal clerks assigned to each department, The Forgotten appeared to have one extra. He instantly started to think about the one random memory he would pull night after night…but quickly dismissed the thought. It was an unheard-of miscalculation. One that he was surely not to question, as it was truly an honor to be assigned as a foreman. So even though it was unusual looking around at the sea of employees, knowing someone may not belong, that wasn’t for him to decide. He was to assign the files, and the clerks were to complete the tasks they were given until the assignment was complete. Deceased.

As soon as Claire awoke Monday morning she reached for her phone. Patrick’s parents answered. She politely asked if they could wake him up so they could talk.

“Hello?” a groggy Patrick exhaled.

“Patches, do you remember Professor Thalmor?!” Claire spat out.

“Who?” Confusion settled in as he wiped his sleep-filled eyes. Claire held the phone to her chest and cried. It wasn’t fair. Why did she have to remember when he couldn’t? She was angry. Her whole life

was attached to someone who was disappearing. Someone with whom she couldn’t create anything new, let alone visit the past.

“Hello?” Patrick said over the muffled phone.

“Nothing, never mind. Go back to bed. We can talk later.” She hung up.

Two weeks later Claire was settled into her dormitory with her brand new roommate, Elise. They were both studying psychology, and they became fast friends. Claire’s new friend. Her second friend ever, and it wasn’t her last. She did exceedingly well in her department, and by the end of year one, she was transferring to Tipletons University, in the School of Sleep Medicine.

She made more friends and more memories. She fell in love and fell out of love. She got a job and got promoted. Doing all this while never forgetting.

Her most honored work was a thesis she wrote that got her recognized in the academic community and furthered her path to graduate school. It was an essay about Patrick, of course. A study looking further into how our brains sort our memories after we’ve fallen asleep titled The Endocrine of Darkness.

In the past four years, Claire had returned home and visited Patrick a handful of times. Each time seeing his memory loss progress worse and worse. This time she sat in her car waiting to go in. The nostalgia nauseated her. Her parents were moving. Selling her childhood home. They had spent the weekend clearing and sorting their own physical representations of memories.

Claire’s hands gently ran over the cover of her old purple journal as she sat in her car outside of Patrick’s house. The first page was marked Things Patches Forgot . Everything that had happened in her life had been a direct reflection of loving him. Most of those things had been great. After a deep inhale, she stuffed the journal in her bag and walked to his front door. Ringing the doorbell, instantly his parents adorned her with hugs. Speaking over each other, congratulating and welcoming her. Looking past them, she saw Patrick’s legs running down the stairs. A sight she had seen so many times it was burnt into her mind’s eye. His parents’ chattering fell off as the two friends met in the middle family room.

“Hi! I’m…I’m…” Patrick smiled while he searched his mind

for who he was.

Claire pulled him in for a hug. Her eyes fluttered back tears. She always expected her file to go missing from his memory one day, but she hadn’t considered him losing himself. She held him tighter, and he returned the favor.

“Patrick. You’re Patrick,” she whispered. That hug lasted as long as she needed, and he would never be the first to let go.

Dance collage

Howie Good

My collages are made the old-fashioned way—with paper, scissors or razor, and glue. They are intended as a counterweight and rebuke to the colonization of culture by algorithms, AI, and other technological tools and corporate techniques. They are also meant to provoke an authentic response in viewers by combining images in a way that upends old habits of seeing. Lastly, the collages often represent a moment or episode in a story whose ultimate meaning remains an intriguing mystery.

Yacht Rock 101

Langston Prince

Chord, though only nineteen and a first-year in college, was, as far as any cardiologist might say, in love. With a girl named Jude. As many college romances begin, they were in the same Yacht Rock 101 class. On the first day of class, the day he fell head over heels for her, the teacher made everyone do an icebreaker. The students were supposed to go around in a circle and say their name and their favorite Steely Dan song. Simple, easy, and effective, and yet Chord dreaded participating—his classmates had only just seen him; now they had to hear his voice? His parents had taught him that social interactions like this were like surgery—they should be taken slowly and carefully.

Jude was sitting to the right of Chord and was going before him. She seemed excited to introduce herself, which frightened him. She said, “My name is Judith Pickett, but call me Jude. Like the Beatles song. In fact, just go Hey Jude if you need me!” Then she paused, expecting laughter. None came. Chord felt a twang of guilt as her hazel eyes passed over him, daring him to let out even a chuckle, but he was set in his ways. He’d found the joke quite humorous, but laughing at a joke on the first day of class was so unbecoming and forward that Chord had ruled it out entirely. This wasn’t high school in California—he was at a premier liberal arts college in Massachusetts! You couldn’t do things as silly as laughing at a joke on the first day of class here. But Jude was beautiful, and her joke had been funny. To make it up to her, he moved his laugh schedule up. Instead of waiting until the eighth class, he’d start laughing at jokes he found funny in the fourth class.

She continued, “You know … Like the Beatles song. Hey Jude. By the Beatles.” Again, she paused, expecting laughter. Again, there was only the painful and awkward roar of silence. “That was a joke,” she said. “Sorry.”

Then, she turned to Chord and prodded him with her elbow. Making direct eye contact, she said, “You’re next. Go.” She was blushing, embarrassment seeping off of her words, but Chord didn’t notice.

“You forgot to say your favorite Steely Dan song,” Chord

stammered. His heart felt like it was pounding out of his chest. He felt the compulsion to materialize a ring on his finger so he could propose to her with it. His mind raced, searching for an explanation: Arrhythmia? Unstable angina? Peripheral artery disease? But all the evidence pointed to something far more terrible: love.

Jude flushed an even deeper crimson and nodded. “Yes. Of course. My favorite Steely Dan song is…uh…‘Dirty Work?’” Then she turned to Chord and ordered him to quickly, please, take his turn. He did and mumbled through it, uncharacteristically forgetting the title of his favorite Steely Dan song because he was so distracted by how beautiful her long lavender hair was and by how her amber skin flushed with undertones of rose when she was embarrassed. The only thing he could think of for the rest of class was how badly he wished she loved him back.

Three months later, with their limbs tangled together between sheets on Chord’s twin XL dorm bed, Jude decided that they should ask each other questions to get to know each other better. Chord was skeptical. In the month they’d been having sex, Jude had never asked nor answered an even vaguely personal question. But since she was offering, he decided to throw caution to the wind. Chord asked, “Do you remember how we met?”

Jude made little attempt to hide the blank expression from her face. It took her twenty-seven long seconds before she recalled enough to begin stumbling through an answer. “Well,” she said, “first, we matched on Tinder. But neither of us messaged first, so…we didn’t message at all.” She glanced to Chord to confirm this was correct, and he nodded. “Then,” she continued, “like…a week later, we matched on Bumble. And I really meant to message you, I did, but I had essays, and I was so busy…” Chord could tell she was lying. To entertain himself for the three minutes she spent making excuses as to why she didn’t message him, he translated her lies into Swedish and imagined it was the Swedish Chef. It was mildly funny and almost distracted him from the bubbling hurt that came from being lied to by the only person he’d ever loved.

Jude wasn’t sure why she was lying. In truth, she had meant to message him and just hadn’t gotten a notification. An honest and frequent mistake made by dating app users everywhere. “...and the match lapsed,” she continued. “But then we matched on Hinge, and by then, I’d seen you more in class, and I’d realized you were kind of my type.” She put extra emphasis on the “kind of.” This was also a lie. After matching on Tinder, Jude began to pay more attention to Chord in class, and she quickly realized that he was, unfortunately, very much her type. When he talked in class, she noticed his voice was pathetic, like a sickly lamb’s mewl. Whenever he wasn’t sure of something, a shaky and fearful timbre infected his tone, which sent excited shivers through Jude’s body. And worse than that, she found herself with the impulse to tie up his long blond hair into a ponytail, kiss him, and see his eyes widen. He seemed like just the diversion she needed. But she didn’t want him to know that. “And then,” she said, “you messaged first with a deeply profound confession of love.”

Now it was Chord’s turn to blush. He had, indeed, professed his undying love to Jude over Hinge DMs. Oh, the inhumanity. And then he’d immediately apologized for how rude he’d been and for any offense he’d caused. Fortunately, she ignored it and asked how his day had been.

“And then,” Jude said, very aware of and pleased with the expression Chord was making, “we went on a date. And you know…” Jude wasn’t too eager to rehash how, after dinner, they’d had sex. And then how, after a few days, she texted him asking to do it again. “So,” she asked, “I’m curious. What made you fall in love with me?”

Chord only needed zero-point-twenty-seven seconds to answer. He told her that it had been really quite simple. The first thing she did to make him fall in love with her was to order him to talk. Chord loved being told what to do—it didn’t hurt that Jude was tall, buff, and beautiful. But in general, being told what to do was easy. It asked of Chord very little; he didn’t have to think critically, he could just do and not have to decide anything for himself. It was how his parents raised him, and Freud be damned, he liked it. The second thing she did was ordering him to talk from a lower social position. Jude had embarrassed herself in front of the entire class. Not once, not twice, but three times had the class witnessed her humiliation, and she still had the gall—no,

nerve—to order him around. Doing that made her the bravest woman, nay, human , that Chord had ever known.

She looked at him for a minute, making no effort to hide her mildly disgusted grimace. Then, without a word and without breaking eye contact for more than a second, she collected her clothes, put them on, and left. This wasn’t the first nor last time she had done this. Fortunately, despite not loving Chord, she would be back. ***

Chord was determined to make loving him as easy as possible for Jude. He made sure to compliment her regularly, especially on things one didn’t usually get complimented for.

“You know,” he’d once said, “you’ve got amazing posture. It’s sexy.”

He figured that was the only way to express the totality of his love for Jude. It wasn’t just that he loved her piercing gray eyes, or her sharp jawline, or her handsome face and roguish smile. He also didn’t just love her for her sly laugh, or for the fact that she refused to go to the gym on Tuesdays, or for how, in Yacht Rock 101, she only knew Daryl Hall’s lines but never John Oates’s. He loved her for all of that and so, so much more. If he could somehow express everything he loved about Jude, and pass a camel through the eye of a needle, then she might begin to love him back.

When they were apart, Chord never bothered or even contacted Jude. She always texted first, usually out of exasperation that he hadn’t contacted her. After two months of this, she confronted him about it.

“It doesn’t make sense!” she said.

“What doesn’t make sense?” he asked.

“That I’m the one always texting you in this…this…”

“Relationship?”

“No,” she said, shaking her head, “not a relationship . We don’t have relations . We’re in a…a…” The word didn’t come, so she continued, “Whatever. The point is: you love me, I don’t love you, so why do I always have to text first?”

Chord nodded and a slow, sad smile spread across his face. His eyes went somewhere distant, thousands of miles and dozens of years

away, and he said, “Well, it’s not fair, is it? I’m already asking so much of you, I just can’t bring myself to ask for more.”

It’s cruel to love another more than they love you. It hurt Chord in ways and places he didn’t know he could hurt. It was a hurt that burrowed its way through his spine and up to his brain stem. It made his muscles feel weak and shaky—as if they’d atrophied from years of lying in a coma. It gave him a looming dread. He worried that loving Jude was the most important thing he would ever do, and she didn’t even love him back.

Sometimes, Chord felt indignant. Why should it be his lot to be cursed with unrequited love? Everyone else got to be happy with their lovers, just not him. And it wasn’t that Jude was incapable of love entirely; she just wasn’t capable of loving Chord. Chord knew that if— when—Jude found someone she could love, he would be left behind. He was not a permanent fixture; she was just waiting for someone better to come along, and then she’d be gone from Chord’s life.

Most unfair of all, six months into their situationship (the name she’d taken to calling it) Jude offhandedly remarked that she was graduating soon. Chord was stunned. It felt like he’d been hit by a truck, and it showed on his face. Jude pretended not to notice. She’d never talked about her personal life because, well, she just didn’t want to, but now she felt guilty. Chord hadn’t known she was a senior. She’d never told him, and it’s not like she’d ever introduced him to any of her friends. They didn’t even talk in class unless they were grouped together. She’d liked how impersonal the relationship was, but now she was thinking she’d kept a bit too much distance.

In a vain attempt to rectify six months of secrecy, she began to casually, carefully, and rapidly tell Chord information about her personal life. Her friends, how her thesis was going, her career plans after graduation, et cetera. He couldn’t hear any of it.

Chord had spent his entire time with Jude wanting to know more about her. She was clear that she didn’t want him to know her and vice versa. There had been a universe of Jude just out of Chord’s reach. He’d wanted to ask so many things—least of all what year she was—but it

hadn’t seemed polite. After all, she’d made it clear she didn’t want to talk about it, and it wasn’t like they were dating—they weren’t even friends. They were near strangers who had sex sometimes.

To make it up to Chord, Jude bought him an expensive signed, limited-edition vinyl pressing of Bobby Caldwell’s 1978 album, Bobby Caldwell . It was a stupid purchase that she’d made on an impulse. It cost more money than she reasonably could afford. She’d originally intended to just apologize, face-to-face. Like a normal person would. But then, for some inexplicable reason, when she thought of doing that, her heart felt like it would pound out her chest, her mind raced, and she decided to buy the vinyl instead.

After Jude graduated, she slowly began to think of Chord less and less. She settled into her new job as an investigative journalist—a far cry from her major in biology—and fell into somewhat of a routine. She was good at her job and certainly didn’t hate it but felt unchallenged and bored. So she began to take on more and more daring and adventurous stories, ranging from a drag queen’s affair with the Sultan of Brunei to an interview with a man who had taken hostages and was throwing bombs at the police. She found herself experiencing, but not particularly enjoying, success. She met many people, saw many places, and did a slew of interesting things, but none of it seemed truly surprising. It all seemed like what she was supposed to be doing. Nothing was pushing her to go out of the mold and dare to be unique. She was not, as far as any cardiologist might say, in love. With anything. And she wasn’t sure why.

She felt as though there was a spark in her life that had been extinguished. And she didn’t know why or how or when it went out, but it was out. And now she was just left with liking life instead of loving it. At night she would lie awake and trace her life, day by day, trying to figure out where it all went wrong. She became determined to find the point where she’d last felt in love. She racked her brain to think of the last time she did something that truly surprised her.

On her thirty-first birthday, while thinking of Chord for the first time in nearly eight years, she figured it out. She thought of his

untrustworthy and lopsided smile, his tall and lanky frame, and how his eyes—which were the colors of the night sky—shone in the dark. She thought of buying that Bobby Caldwell vinyl. She thought of that stupid, stupid purchase that had financially disrupted her life for nearly a year. She wondered why she’d done it. Then, she realized. In that instant, she had fallen in love with Chord. And she still was in love with him. Now she just had to find him. So, she got to doing what she did best: she investigated.

Chord spent a long time missing Jude. At night, as he lay awake thinking of her, he could almost bring himself to anger over how she’d treated him, but his fiery passions would quickly retreat, and he would return to depressed melancholy. To distract himself, he tried to imagine a world where he never fell in love with Jude. A world where he’d never taken Yacht Rock 101—or maybe just sat one or two seats to the left. A world where love hadn’t exploded into his heart and made him do so many stupid, rude, and brave things, least of all telling Jude that he loved her. A world where he could be lying awake stressing about his Swedish class instead of a woman he’d only known for nine months. He considered texting or calling Jude to explain to her how he felt, but his emotions and thoughts were too scrambled to come up with anything he felt was sufficiently coherent. So he didn’t contact her. And as days wore into weeks wore into months wore into years, Chord’s window to contact Jude disappeared. By the time he graduated with honors and a double major in yacht rock studies and statistics, Chord had mostly convinced himself he was over Jude. His parents were proud of him and glad that he decided to major in yacht rock studies. After all, it was a respectable and highly paid field with a lot of career opportunities—not like that dead-end major statistics. God forbid their son shame them by becoming a statistician. They urged him to go into academia and become a professor, because who was more respectable than a professor? Not knowing a life outside of schooling, Chord agreed and enrolled in a prestigious California graduate school to become a professor of yacht rock and statistics.

Then, at the age of twenty-three, Chord won the lottery. He’d only bought the ticket to prove how statistically unlikely it was to win the lottery to a student. At first, Chord didn’t tell anyone, but word got out. Messages from friends and family poured in. Most told him to invest his money and maybe buy a house—it would set him up for a prosperous, normal, and sensible future. Chord relented, ignoring a nagging feeling in his gut. He spent months looking for a house near his university. Finally he found one. It was a four-story brownstone with enough space to raise a family but not enough space to seem eccentric or extravagant. In a word, it was a perfectly normal and sensible house for a prosperous individual. And Chord was almost happy. But that feeling of dread just wouldn’t go away. As he was about to sign the deed, Chord suddenly realized what was wrong: he wasn’t happy. With anything. And he knew why and just what to do.

Chord ripped up the paperwork and rushed back to his apartment, where he began to pack his bags. Four days later, in a single email, he notified his friends, family, and university that he was completely abandoning his life path as they understood it. He was dropping out of university, selling most of his worldly possessions, and moving to Stockholm, Sweden. A follow-up email informed them he’d been in Sweden for a few days already, so it was too late to stop him.

In Sweden, Chord enrolled in the Stockholm Maritime Academy, the premier maritime academy in Europe. While obtaining a captain’s license and studying sailing, he befriended a number of hearty seamen, seawomen, and seapeople, who were unlike anyone he’d ever known before. After finishing his education and getting his captain’s license, Chord bought a fishing vessel and named it Gaucho . Then he called up a number of his new friends and formed a fishing collective that operated out of the Baltic Sea.

His parents were dismayed. While visiting his apartment in downtown Stockholm, after making disparaging remarks about his unorthodox interior decoration that took inspiration from surrealist painter Max Ernst, they began to insist that he’d misunderstood the point of yacht rock. Yacht rock wasn’t music for people who owned boats—much less fishing vessels that sailed the icy waters between Finland and Sweden—it was music for people who wanted to own a boat. But like, a fancy boat. A yacht . Not a fishing vessel. Yacht rock

was music for sensible, normal people who only dreamed of normally exciting things. It was music for professors of yacht rock and statistics who dreamed of owning a yacht. It wasn’t music for crazy, abnormal people who were doing abnormally exciting things. It wasn’t music for Chord.

Chord knew the point of yacht rock. He’d majored in it, damnit! Storms would come at sea. Coaxed on by cold and warm air mixing over Scandinavia, dark and ominous clouds would spew rain and lightning. Baltic waves the color of the midnight sky would crash onto the side of Gaucho , tossing the boat around, threatening to sink it. Chord would scream orders at his crew while blasting the Bobby Caldwell vinyl Jude had given him over the ship speakers if just to drown out the thunder. And while he wasn’t the one taking the orders, and captaining a ship required a shocking amount of critical thinking, and he had to do so many rude, brave, and socially awkward things every day, and he could never ever wait for the polite or proper time to say or do something important lest Gaucho and its crew sink into the Gulf of Bothnia, Chord loved his life.

When those storms would break and it was just Chord, his sailors, and “What You Wouldn’t Do For Love” drifting gently from Gaucho ’s speakers, Chord would take a deep breath. In that moment, Chord could say he truly loved his life. He loved his life more than he’d ever loved Jude. At night, drifting off to sleep, lulled by the gentle snoring of the crew and rocking of the boat, Chord no longer wondered about what could have been. For as many mistakes and blunders as he’d made, for all the pain and misery he’d experienced, Chord didn’t regret any of it because it had led him to be on Gaucho , truly happy and truly in love.

Then, one day, while Gaucho was docked for refueling in Gothenburg, Jude found Chord. She’d been searching for a year, following breadcrumbs to Sweden. As soon as she saw him, she knew: it was Chord. But he’d changed so much. His long blond hair that she’d tied into ponytails was now accompanied by a scraggly beard. His smile as he greeted her was warm and inviting. His lanky frame had filled out; he’d become muscular and broad. His doe-like eyes now had a peace

to them that recalled waves lapping at stone beaches. And worst of all, as he talked, Jude realized his voice had changed. It wasn’t a sickly, pathetic mewl anymore but instead a confident, booming symphony full of happiness and gravel.

Trying to ignore the crowd of sailors who were clearly pretending to be busy while shooting suspicious glances at her, Jude cleared her throat and said, “You seem…healthy.”

Chord smiled and Jude hated him for it. His smile still had hints of mischief in the edges of his mouth, but it didn’t seem forced anymore. He seemed content in a way she couldn’t understand. She got the feeling that he knew something she didn’t. “I am,” he said. “I’m—”

“I’m in love with you,” Jude said, cutting Chord off. Her hand shot to her mouth, trying to stop the words, but they’d already come out. Trying to make the best of a bad situation, she stared into Chord’s eyes, waiting for them to widen and for his doe-like innocence and fear to return. They didn’t. He just looked tired and somehow a decade older than he had just ten seconds previously.

The two of them sat in silence for two of the most painful minutes of Jude’s life. Finally, Chord broke the silence. “That vinyl you gave me,” he asked, “how much was it?”

“$750.”

“How much would that be worth today?”

“$750 plus inflation.”

Chord sighed and pulled out his wallet, taking out all the American dollars he had in it. “Why don’t we call it $1,000?” he asked. Jude nodded. It felt like she’d been hit by a truck, and it showed on her face. Chord shouted a few words in Swedish to his crew, and they began to line up. One by one, they exchanged Krona, Euros, and IOUs for dollars. Finally he handed a thick stack of bills to Jude and said, “There. I’m buying it from you. You can do whatever you want with that money, but I’m leaving soon, and you can’t follow me anymore.”

Jude took the money as if in a dream and counted it slowly. It was exactly $1,000. “But,” she said, her voice breaking, “I love you. And you love me. I came all this way for you. Doesn’t that mean something?”

Leaning back in his chair and looking at the sky, Chord could only think of how beautifully blue it was. “That might be true,” he said. “But I think it’s time to move on, don’t you?” He made eye contact

with Jude, and she shivered. “It’s been a long time since we’ve seen each other. We’ve both changed. And I could sit here talking about how I don’t think you actually love me, that you’ve just convinced yourself you do, but that’s all moot anyway. The bottom line is: I’m afraid I’ll get hurt.”