Woody G wy n

CONTINUED DOMINIONS

In approaching a Woody Gwyn painting, it’s helpful in understanding that, for the artist, the quotidian doesn’t exist. The divine is everywhere. To stumble on a quiet spot in Villanueva, or any other remote village in Northern New Mexico, and perceive in its wilds an idyll reminiscent of the South of France, perhaps someplace where Claude Monet would feel at home, takes a certain kind of seeing.

Leaning on the wall in his studio in Galisteo, New Mexico, in late February, one large-scale painting is nearly complete. In it, a tree-lined hill rises alongside an atmospheric seascape, whose waters vanish in a bright haze. A stretch of winding highway, high up in the hills, adds contrast. It’s the scene’s only unnatural element. But it too gleams under the illuminating sun. The beauty of the terrain doesn’t end where the tarmac begins. It pervades the entirety of the scene. On the one hand, you could consider Gwyn’s fidelity to the landscape and the road equal in measure.

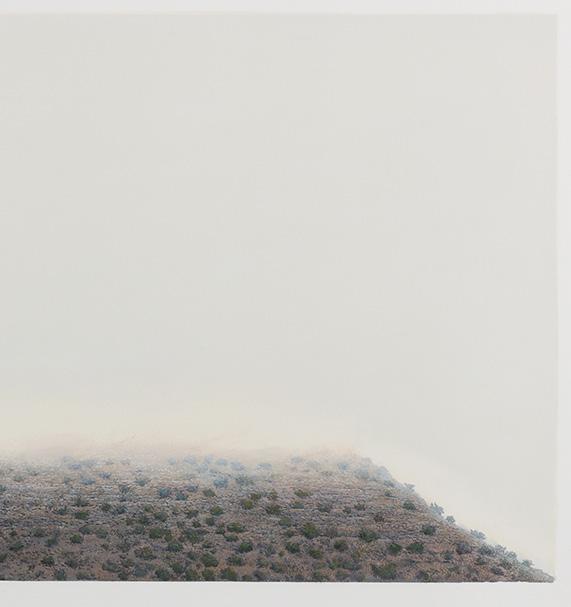

On a nearby easel, a much smaller oil depicts a basaltic embankment in the Galisteo Basin known as El Crestón (or Comanche Gap), a subject he’s painted before. He approaches it from a different angle than the earlier piece (Comanche Gap I) and the compositional framework is panoramic and rectangular. Gwyn, finds inspiration outside his front door as readily as when he’s driving along the Pacific Coast or touring the cities of Europe. One of the nation’s leading landscape artists, he approaches each subject from an atypical vantage point, cropping the scene, which he often captures first in a photograph or sketchbook and translates to canvas back in the studio, for dramatic effect. Each carefully rendered, minute detail reflects a cohesive, overall treatment that’s unmistakably Gwyn. But “stylized” isn’t the word we think of, like we do when we see a certain type of non-realist treatment of representational imagery, as in a work by Jim Vogel or something similarly redolent of magical realism.

Gwyn, rather, peels back the film from everyday reality, allowing us to apprehend it, unmarred by intrusive thought. He presents the viewer with something pure, the “Aha” moment gleaned in the stillness of nature, when we’re unaccompanied and alone and our thoughts melt away. As Ken Marvel, owner of LewAllen Galleries, observed in his essay for Gwyn’s 2015 exhibit Solitary Places, “Even the ‘empty’ ocean or desert invites the viewer to a place full of quiet and comforting awe.”

It is almost as if Gwyn makes it that much easier to experience aesthetic arrest, because his intent, from the start, is to reflect the empyrean beauty that is.

“How can you look at a lily pad or a haystack and not think of Monet?” he said during a recent studio visit. “Would you have normally looked at a haystack? No. Not normally. You wouldn’t really see it the way Monet made you see it.”

By that same token, Gwyn’s work is expansive, because it reaches outside of the interior gallery space to superimpose itself on the world around us. His vision becomes ours. Driving from Gwyn’s home in Galisteo, New Mexico, in route to Santa Fe, for example, the highway curves through mountainous terrain, guardrails gleam under a bright sun, and ochre hills studded with scruffy sagebrush contrast with the bright, white elements of the road. You see it as Gwyn sees it, and the scene before you coalesces polyphonically.

If you find yourself saying “it looks like a Woody Gwyn painting" rather than the other way around, it isn’t a question of life imitating art but a question of looking. Life is art. He’s peeled a veil away for us, impacting how we see in a way that verges on a near-mystic understanding of a unifying principle. One gains an appreciation for the opalescent colors revealed in water, rock, wood, metal, concrete, and tarmac under the sun’s fleeting light. We retain this perspective from rural to urban settings; from a landscape of Eastern forests or Western canyonlands to the choking traffic of a concrete jungle, the world of ordinary things is a world of beauty. His subjects are the elements of earth, water, sun, and sky, and he treats landscape with reverence, as though it already exists as a work of art before he paints it, composed by an unseen, divine hand, whose brushes are erosions, winds and the fingers of time.

The work is expansive, whether it’s rendered large or small, stretching the eyes.

Born in San Antonio, Texas, in 1944, and raised in the West Texas town of Midland, which had an active art scene, Gwyn gained a reputation as his elementary school’s resident young artist. From about the age of 12 up to now, Gwyn’s painted nearly every day. Rather than a dusty, colorless backwater (the type of place from which an ambitious young artist longs to escape) Midland was a haven of inspiration, and he found opportunities to hear lectures from visiting artists, including Richard Diebenkorn and Milton Resnick. He pursued his artistic inclinations to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, while also seeking instruction directly from prominent artists such as Roswell, New Mexico-born landscape painter and portraitist Peter Hurd and Carolyn Wyeth with whom he studied under while living as a student in Pennsylvania in the early to mid-1960s.

Gwyn, who received the 2010 New Mexico Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts, is a longtime New Mexico resident. “I really never left Texas,” he jokes, recalling that the Galisteo area was, briefly, a part of our neighboring state. Here, the desert landscape, like the West Texas of his youth, is broad, spacious, and, as such, invites seeing. For his May exhibition at LewAllen Galleries, Gwyn is presenting a series of acrylics, oils, egg temperas, and monotypes, some of which he’s gone over with gouache or watercolors, demonstrate that show scale is relative. Known for works whose size is often large enough to create a near-immersive experience for the viewer, works as small as 2-by-6 inches in height or width are not uncommon in the artist’s portfolio. These works, along with a selection of large-scale paintings, resonate as part of a singular vision.

“I go from one extreme to the other,” he said. “You can be gestural with big things or with small things. They all have the same difficulties.”

Composition isn’t something Gwyn creates so much as something he discovers in the world around him. But he frames it. And his cropping can be severe, as when he paints panoramic vistas in narrow bands that stretch horizontally across a rectangular canvas. And the cropping can be literal. He recently found what he felt to be a better, more impactful composition by sawing off several feet of a monumental painting, canvas and all. Gwyn also injects a playfulness into his work, adding elements that are disparate, such as a steel guard rail, and the lines of the road, but that echo one another. This dialogue between different aspects of his compositions is the result of an abstract way of seeing. For Gwyn, understanding a realist composition involves a measure of abstract thinking and viewing.

And abstract painting. Up close, details lose clarity, but coalesce into a vivid, impactful, pastoral scene or a seascape that belies its simplicity. It looks more detailed than it is.

Like Dutch Baroque painter Johannes Vermeer, who, Gwyn points out, had such a sharp compositional focus, you could turn one of his paintings any which way and it would still be interesting in terms of how all the elements work together, the landscape artist hears the conversation between the rudiments of a scene. There’s often an underlying pattern beneath an artist’s canvas, which the viewer never sees: a light sketch, perhaps, or underpainting. A pattern exists in nature too, uniting every shimmer of light on the surface of the sea to every sun-dappled tree lining the coastal highway.

Gwyn doesn’t capture it so much as he reveals it.

— Michael AbatemarcoCondor Pass, 2022-23

Egg tempera on panel, 48" x 84"

Pacific, 2022-23

Egg tempera on panel, 4" x 12"

Estuary VIII, 2022-23

Estuary I, 2022-23

Oil on panel, 5.25" x 13.25"

Near Ragged Point, 2017

Mixed media on Paper, 10" x 13"

Mixed media (monotype), 17.63" x 35.13"

October Sun I, 2022

Oil on panel, 4.5" x 9.75"

Egg tempera on panel, 3.63" x 9.25"

Full Moon, n.d.

Egg tempera on panel, 3.88 x 4 in.

Acrylic on panel 8.75" x 4.25"