ELIAS RIVERA

IN PRAISE OF THOSE WHO ENDURE

ELIAS RIVERA

IN PRAISE OF THOSE WHO ENDURE

September 27 - November 2 . 2024

PREFACE

A profound visual storyteller of intimate moments related in saturated vibrant colors and sculpted by golden light, Santa Fe-based figurative artist Elias Rivera (1937-2019) was best known for his rich narrative paintings that celebrated the dignity of daily life in various Latin American cultures. The truthful figures that palpably emerged in his paintings are rendered from complex layers of colors and mirror the emotional layering the artist brought forth in his subjects — stoicism with dignity, simplicity with splendor — that above all honored their humanity.

Rivera granted them the heroic representation that was previously afforded only to titled aristocracy and prosperous merchants memorialized in portraits by Old Masters. Utilizing the tools and techniques of those same revered artistic forebears, Rivera quietly argued in his paintings for the modest nobility and spiritual wealth that could be found among the market vendors and produce sellers in Guatemala or Mexico.

Rivera elevated the simple acts of life onto large-scale paintings in which his sensual colors carried emotional charge, and reality was heightened to a the level of an authentic cultural stagecraft. As a new kind of painter of light, Rivera was composer, director, and cinematographer of energetic scenes that unfolded with an irrepressible aliveness, an exceptional quality that distinguished him as a modern master of figurative painting.

Untitled (Self-Portrait), n.d. Oil on panel

20 x 16 in.

THE NEW YORK YEARS

Though Elias Rivera found his heart inspiration, receptive audience, and even soul partner (in artist Susan Contreras) after relocating to Santa Fe in 1982, his seeming overnight success was in fact bitterly hard won. The then 45-year-old’s skillful and evocative paintings that garnered immediate attention out West were a result of grinding dedication to his practice for several bleak decades in New York. Born in the Bronx to Puerto Rican parents, Rivera came to realize he had access to all the resources that the big city had to offer a young man interested in art — chief among them the renowned Art Students League, where he studied from 1955 to 1961. Under the tutelage of Frank Mason, Rivera fully embraced figuration at a time when New York was the epicenter of abstraction, which consequently left painters like him on the fringe. His deep interest in the rights and issues of the common man, however, made his attraction to figuration inevitable. Some of his most charged paintings of the 1960s depict Vietnam War and civil rights protests, which captured the drama of the moment while acknowledging the figures’ poignant individuality in the shared struggle. With a Goyaesque sense of haunting intensity, he also captured the less-seen, less glamourous parts of everyday life in New York: its subways, waiting rooms, automats, and airports.

Outdoor Show, New York, 1960

Waiting Room, 1975 Oil on panel 9 x 10 in.

Subway #2, 1975

Oil on canvas

16 x 20 in.

Untitled (Automat), n.d. Oil on panel 15.50 x 22.38 in.

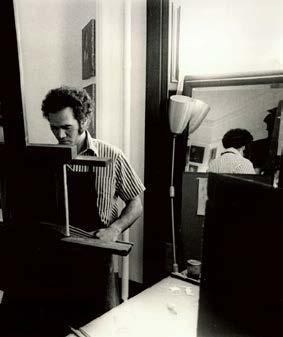

Early Self Portrait from Arts Student League, n.d.

Oil on board

11 x 9 in.

John Miller, ca. 1971 Oil on canvas

28 x 24 in.

Airport (triptych), 1975

Oil on panel

8.25 x 38.75 in.

NEW MEXICO AND A NEW BEGINNING

It would not be an overstatement to say that Rivera’s move to Santa Fe, New Mexico not only changed his life but saved his life. Several health issues he faced upon his relocation were what he later believed to be a purging of New York’s toxicity and its effects on his body. As a student of Old Masters and their deftness with employing light and shadow, Rivera was foremost struck upon his arrival by the dazzling light. Drawing upon his background in set design, among the many odd jobs he had in New York, Rivera set the stage, found the character motivation, and spun a spellbinding narrative. “I wanted to paint the theater of life,” Rivera said in a 2006 interview. “I was driven to paint people in their own world, to honor them in their own realities.” This urge brought him to observe the vendors under the portal in the downtown Santa Fe Plaza, and to the Downs at Santa Fe racetrack to watch the jockeys and grooms. Rivera drew upon all his hard-earned New York experience, through not only a dynamic application of paint but more importantly his empathetic understanding of the individuality of the people to whom he felt a new zeal to bear witness. He painted all of them with dignity and integrity, declaring that he wanted to capture the aspects of life that others don’t often see.

Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1982

Waiting at the Paddocks (Santa Fe Downs), 1984 Oil on canvas 20 x 30 in.

Matachine Dancers, 1986

Oil on linen

12 x 9.50 in.

Cerillos, ca. 1980s Oil on canvas

12 x 24 in.

OAXACA PAINTINGS

The 1980s marked a period of joyful artistic experimentation inspired by numerous trips to Mexico, starting with Oaxaca. As one of Mexico’s most ethnically diverse states, Oaxaca turned out to be a revelatory place where Rivera encountered its many Indigenous peoples at crowded markets and festivals. Photography was essential to his work from this new artistic era, though it had not been a part of his toolkit until the 1980s and the influence of Contreras. With long lenses, he could capture unguarded moments during his discreet observations of festivities around Holy Week and Easter. A three-week trip would result in hundreds of slides. A city boy and an only child, Rivera was a master at people-watching. As in a New York subway car, once his subjects noticed they were being observed, he in turn looked away — the honesty of the moment, he believed, already lost. By viewing his subjects through a camera, Rivera had the space to think more cinematically and was able to compose scenes like a director, sometimes knitting together elements from multiple exposures. Though he utilized photography as a tool, he was not a photo-realist in intention or in style. The truth he sought was not the accuracy of a documentarian but rather a verisimilitude of emotion.

Oaxaca XVII, 1985

Oil on canvas

9.50 x 12 in.

Oaxaca VI, 1988 Oil on canvas 16 x 20 in.

Oaxaca Market, 1984

Oil on canvas

24 x 32 in.

Untitled (Woman from Oaxaca), n.d. Oil on canvas 14 x 11 in.

Oaxaca Midday Break, n.d.

Oil on canvas

36.25 x 48 in.

Right: Detail of Oaxaca Midday Break

THE TARAHUMARA

Elias Rivera’s constant awareness of and curiosity about other people, as they moved and lived in their environments, was crucial to this next phase of his artistry that developed in the 1980s. Prompted by Rivera’s interest in capturing the Matachine dancers in Bernalillo, New Mexico, Contreras suggested they travel to the Sierra Madre Occidentals of northern Mexico to see the Tarahumara, a visit that would completely transform his worldview. One of his early paintings from this new era, Women of Tarahumara III (1987), retains the introspective quality of many of his New York scenes — with figures grouped together but each in their own inner worlds — that became a fitting portrayal of the reclusive and independent Tarahumara people, who are little changed despite hundreds of years of exposure to Spanish, Mexicans, and missionaries and who only come together as a community for festivals and events. He was captivated by the distinctive reds of the Tarahumara women’s patterned dresses, marveled at the self-possession etched in their faces, but they are nevertheless situated half in shadow, half in light — similar perhaps to his personal transformation of emerging from a particularly desolate period living in New York. Evident already though, is a shedding of the atomized existence of the city. Prior tohis visit, for instance, Rivera gained the required permission of the Tarahumara to photograph them, a sign of the kind of respect and eventual trust he would earn from his subjects in often secluded communities.

Tarahumara Women, ca. 1987

Oil on canvas

10.50 x 13.50 in.

Tarahumara, ca.1986

Oil on canvas

16.25 x 12.25 in.

Women of Tarahumara III, 1987

Oil on canvas

36.50 x 48 in.

Right: Detail of Women of Tarahumara III

THE HIGHLANDS OF GUATEMALA

Within a decade, Rivera had stepped into a renewed confidence that his hand, heart, and vision were aligned in the right place and time. This artistic self-assurance is clearest in his paintings of the people in the highlands of Guatemala from the 1990s and 2000s for which he is perhaps bestknown and celebrated. “When I finally started visiting Guatemala,” he said, “that’s where I found the true heart connection my work needed.” It was at this time that Rivera began to consistently paint on a large scale, sometimes six to seven feet in height. Many of the figures in his paintings are trueto-life-sized. In Light of Life (1997), Rivera’s sense of rhythm and exceptional gift for color create an engaging tableau, but it is his command of light, bending it in arcing lines and suffusing corners with a golden glow, that lends the scene a tangible presence. The composition extends to the very top of the canvas as the basket of carrots nearly brushes the upper edge. The bushy tassels create a rhythm of color across the scarves and shawls and curve upward toward the leafy stems. A strong raking shadow from the right, however, brings a dynamism to the painting in stark contrast to the luminous soft contours of the figures. He loved children, women, and the pairing of mothers with their babies, a subject matter not historically well explored outside of religious contexts or, in the modern period, by male artists. Rivera portrayed them with great sensitivity and visible delight. Combined with his aptitude for the theatrical, the sheer scale of his Guatemala paintings burst with a colorful aliveness.

In the markets of Alomolonga, Guatemala, 2005

Flowers of the Mind #5 2002 Oil on canvas

50 x 60 in.

Blue Blanket, 1994

Oil on linen

70 x 52.25 in.

Right: Detail of Blue Blanket

Chi Chi Castenango, 1993

Oil on canvas

48 x 72 in.

Right: Detail of Chi Chi Castenango

Untitled, 2008 Oil on canvas

60 x 84 in.

A Time Apart, 1995 Oil on canvas 84 x 42 in.

Feast of Fools, 1995

84 x 41 in.

Oil on canvas

Shepherd, 2011 Oil on canvas

47.75 x 36 in.

Untitled, n.d.

Oil on board

12 x 10 in.

Untitled (#16), n.d. Oil on panel

12 x 10 in.

Untitled (Woman & Child), n.d.

Oil on canvas

14 x 11 in.

Market in Todos Santos, Guatemala, n.d. Oil on panel 12 x 10 in.

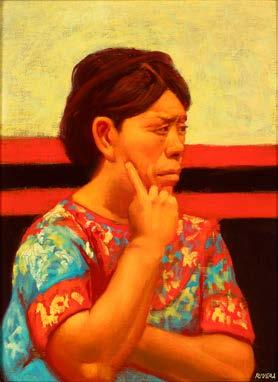

Untitled (Woman Thinking), n.d.

Oil on canvas on board

12 x 9 in.

Untitled (Woman & Child in Market), ca. 2000 Oil on panel 12 x 10 in.

Untitled (#30), n.d. Oil on panel

12 x 10 in.

Untitled (Woman in Traditional Garb), n.d. Oil on board 14 x 11 in.

Windows of the World #35, 2003

Oil on board

12 x 10 in.

Windows of the World #43, 2003 Oil on board 12 x 10 in.

Windows of the World #19, 2003

Oil on board

12 x 10 in.

Windows of the World #41, 2003 Oil on board 12 x 10 in.

Windows of the World #26, 2003

Oil on board

12 x 10 in.

Windows of the World #18, 2003 Oil on board 12 x 10 in.

Portraits of Peru #5, 2000

Oil on board

10 x 8 in.

Portraits of Peru #15, 2000 Oil on board 10 x 8 in.

Portraits of Peru #17, 2000

Oil on board

10 x 8 in.

Portraits of Peru #23, 2000 Oil on board 10 x 8 in.

Untitled (Side Profile of Young Male), n.d. Oil on panel

10 x 8 in.

CONCLUSION

According to Contreras, Rivera would paint while listening to music, the act of painting a dance, sometimes even dancing himself (another of his many jobs in New York), transmitting a vitality that translated beautifully onto the canvas. Contreras once called his process “dancing his way through the painting,” and the unbridled joy he found in his artistry, paired with the profound dignity he accorded his subjects, has given us some of the most masterful and memorable figurative paintings of our times.