HUNTING 2023

HUNTERS SEEK TROPHIES TO LAST A LIFETIME

A special publication of

OUTDOORS SECTION | FRIDAY, SEPT. 9, 2023

Fall is here, or at least nearly so.

dreamed up over the long, hot summer.

If you go by the arrival and passing of the autumnal equinox when nights become longer than days, we are not quite there. But if you measure it by a crispness in the morning air and the ever-expanding opportunity to take to high ridges, jagged canyons, green meadows and the tawny edges of agricultural fields in pursuit of blue and ruffed grouse, bull elk or mourning doves, it’s here.

It starts with just a trickle of opportunities — a tease almost. Then grows to a gushing flood with too little time to do everything you

Should you chase chukars and Huns in September or bugling bulls? Should you devote October to steelhead fishing or rifle hunting? Should November be reserved for rutting whitetails or wily roosters with long tail feathers and the fighting spurs to match?

The answer is yes. Do it all, as fast as you can. The days are getting shorter. Winter is not far off. Don’t let the opportunity to harvest not only game but also the memories and experiences that are the true trophies of the hunt slip away.

The people featured in the 2023 Hunting Edition have

done a fine job of packing their mental freezers full of meaty memories. There’s a story about Gordon Lyons, a wild sheep hunter with an uncanny ability to draw control hunting tags. Another features Anna Call, a young deer hunter from Clarkston who has killed five bucks in six years. Jeff Benda of wildgameandfish. com shares recipes and the story of how hunting changes his perspective. Ralph Bartholdt, a former Tribune reporter, shares a wonderful essay about his first bow and the world it opened up. Check them all out and get busy packing away hunting experiences.

— Eric Barker

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

Luck is rewarded by preparation. Gumption is not a bad partner either.

Gordon Lyons has all three. Blessed

Let’s start with luck. Some people try all their lives to draw trophy big game hunting tags in Western states. For example, to hunt wild sheep in Idaho and Oregon, you have two choices: Purchase the tag at auction or win an annual drawing. If you go the auction route, expect to spend six figures and compete against hunters with pockets as deep as Hells Canyon.

The other option is to enter the states’ annual controlled hunt drawings where you shell out a few bucks to purchase a single chance at winning. The tags are few, the demand is high and the odds are not in your favor. Anyone who is successful can rightfully be described as lucky.

Lyons, of Flowood, Miss., drew a tag to hunt Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep on the Oregon side of Hells Canyon in 2009. But his luck didn’t end there. Lyons drew Idaho’s Unit 11 tag in 2018, one of the most coveted bighorn hunts on the planet.

“I’ve got an adult son who is in med school and his friends have told him, ‘Your dad is paying someone off. We know it.’”

With that kind of luck, some folks might say something like, “You should be buying lottery tickets.”

ABOVE:

the horns from a ram he shot on the Oregon side of

Not much for gambling, Lyons instead entered the controlled hunt drawing for a 2023 California bighorn sheep in Idaho’s Unit 40. Of course, his name was drawn. Even he can’t believe it.

“I have drawn these honestly, ridiculously, through the random draw,” he said. “It’s like how did that happen? With sheep hunters, you mention drawing tags and their eyes roll back in their heads, they have

slight tremors and they are about to go into grand mal seizures.”

Lyons grew up on the Gulf Coast of Mississippi where he hunted scraggly whitetail deer. The habitat isn’t great

for growing trophy bucks — acidic soil, swamps, brambles and little if any agriculture to augment their diets.

“A big whitetail deer in southern

> See LUCKY, Page 5

Mississippi was 157 pounds and that was huge,” he said. “An average buck weighs 129, 130 pounds.”

Boone and Crockett whitetails or not, he loved it.

“Hunting is not about killing,” he said. “It’s about seeing a red cockaded woodpecker, seeing wild turkeys, having a bobcat walk past you that doesn’t know you are there, hearing the water in those little creeks, the wind blowing through pine trees — it’s kind of like being in a medieval cathedral surrounded by artwork.”

Lyons is drawn to outdoor writers — people like Aldo Leopold, Jack O’Connor, Jack Curtis, Russell Chatham, Lefty Kreh, Charles Sheldon and Thomas McGuane. Their work frequently extols the virtue of doing difficult things in difficult environments whether with a fly rod or rifle. It inspired Lyons.

“I was thinking, while I’m still young enough, how do I really push my physical and mental limits?”

He landed on sheep hunting and put in for that 2009 hunt in the stark, steep and stunning Imnaha River country.

The river flows out of the Eagle Cap Mountains and cuts an impressive gorge layered with impossibly steep ridges before joining the Snake River in Hells Canyon. It’s a nearly vertical world inhabited by tough and wily sheep, both of which granted him the challenge he sought.

“It pretty much whipped my ass every single day,” he said. “Every day it rained or sleeted.”

A novice, he knew he wanted the help of an outfitter and meticulously screened candidates before landing on Jon Barker, of Gifford. He pored over maps, practiced shooting and followed a strenuous workout regime prior to the hunt.

The work

They didn’t see anything on the first day. Lyons missed a ram at 530 yards on windy day 2.

They saw rams the next two days but couldn’t get a shot at the ones Lyons liked and passed up shots on others. On day five, it poured rain and the wind blew hard. They spotted a ram group and made a three-hour traverse to get in position for a 225-yard shot. He was soaked and cold enough to require a change of clothes before attempting a shot.

Lyons, Barker and his guides studied the four rams with binoculars and spotting scopes to pick out the largest. Finally one of the guides said, “Shoot the one in the middle.”

“I turned and said which one in the middle?”

Second from the right he was told.

tags in Idaho and Oregon

“Can you make the shot?” Barker asked.

“Yeah, I can make the shot,” Lyons answered and then squeezed the trigger.

“He collapsed like a sack of potatoes.”

Lyons, a dedicated journal writer, still has notes from the hunt.

“I was elated and exhausted,” he said reading the entry. “It was the hardest physical and mental challenge I have ever attempted. I now know what it means to have sheep fever.”

By the time Lyons drew his Unit 11 tag, he devoted himself to pursuing wild sheep and had completed successful hunts for dall and stone sheep in the Yukon Territories of Canada. He teamed up with Barker again and they sought a monster ram with an estimated Boone and Crockett score of 194 at the north end of Unit 11 south of Lewiston.

“The ram went into Red Bird Canyon and would not come out,” he said.

The canyon, state land managed by Idaho Fish and Game, was off limits to outfitted hunting. So after a week, Lyons went home with a plan to return later in the fall.

When he did, Barker instructed him to prepare to spend six days hiking and camping in Hells Canyon. They would sleep on thin, backpacking air mattresses and use Tyvek construction wrap to keep off the dew and rain.

“I slept like a baby,” he said. “The moon was quite bright and it just made the whole nocturnal scenery. It was, for lack of a better word, a sensual experience.”

On the third day, the men worked hard to find a group of 10 rams just as the sun was setting. They slipped just over a ridge, out of sight of the sheep, and bivouacked. Up before the sun, they moved into what they figured would be an advantageous position.

“As it got daylight there were rams between us and where we slept, rams to our northeast on our side of the canyon and two rams to our left or southwest on our side,” he said. “As it got more light we could see six rams on the opposite side. It took Jon and Ted (one of Barker’s guides) a good two hours to figure out which one was the oldest. I’m not kidding, they all looked big to me.”

With the biggest identified, Lyons stacked two backpacks on top of each other for a rifle rest on the steep slope. But he was sliding and un-

steady. Barker told him to put his feet on Barker’s shoulders to steady himself. Lyons wanted to move to a flat rock the size of a tool chest 30 yards away where he would have a more comfortable shot, but Barker feared the rams would see them and run.

So he shot and missed from the awkward position. All of the rams startled at the crack that echoed around the canyon and went on alert while looking for its source. Lyons and Barker scrambled to the rock. He aimed and shot just as the ram was about to run.

“I shot him right through the heart at 265 yards,” he said.

They dressed it out and packed the cape, head and meat to a cobble beach at the bottom of the canyon. The next day they were picked up by a jet boat.

The two will be meeting up soon to pursue a California bighorn ram in Owyhee canyonlands of southwestern Idaho.

“When you step back from it, that is lucky,” Lyons said of his three tags. “But you need to be prepared if you are lucky.”

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@ lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273. Follow him on Twitter @ezebarker.

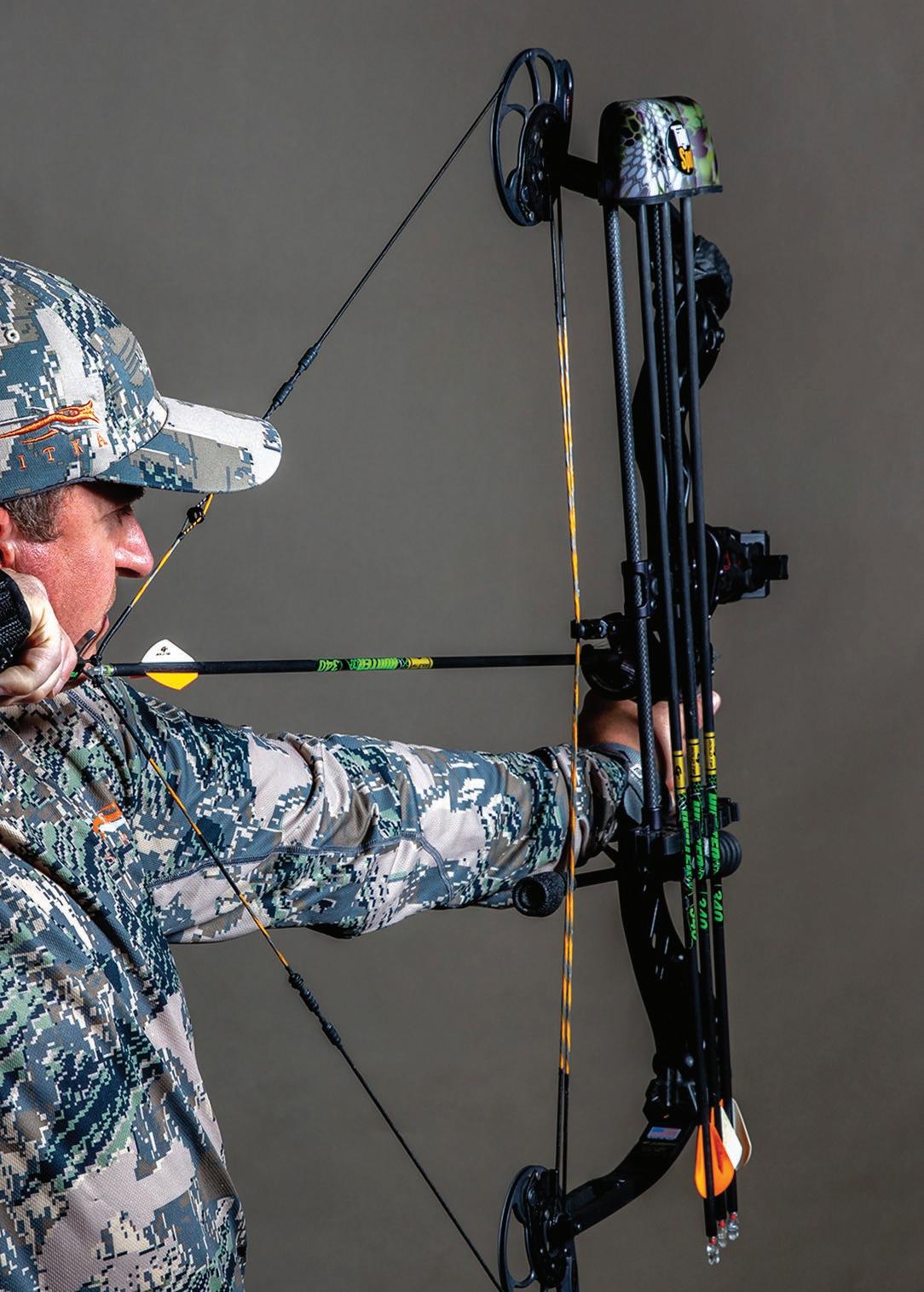

Mybow has wheels and the arrows have three razors.

The points I use on targets look like tiny Kyrgyz hats made of hardened steel. They drive into blocks of foam so deep it takes two hands and elbow grease to pull them out.

I know just as much about archery today as I did 20 years ago when the guy in the store in a small town with a fiberglass elk overlooking the main street said, “Walk this way.”

I had been perusing cheap ammo, running my fingers over topwater lures and ceramic tableware with duck motifs, burning time because back then time seemed plentiful as tinder.

owner hung ice augers and Christmas ornaments there.

“Touch that trigger,” he said, and the floor creaked. The string twanged softly and the arrow tarried forth like the tongue of a snake after a cricket. It plugged the target where I had pasted my eye, or pretty near that place.

“Put your hand right here, inside this braided leather loop,” he said, thrusting an archer’s bow in my direction. “Use this gizmo to pull the string.”

I instinctively followed his instructions because nearly every month for several years a portion of my paycheck was entrusted to this shop owner and he regularly steered me away from poor purchases with four words.

“You don’t want that,” he would say, adding something about out-oftowners who took to shiny things like camp jays, and who possessed the pecuniary pluck to follow through.

“This one’s for you,” he would declare as if he could smell the sweat on the remaining bills in my pocket.

When I peered through the bow’s peep sight as big as a puka shell, my arrow pointed at a block of foam against a wall in the back of his store. In winter, the shop

“Waddya think?” he asked.

“Huh,” I ventured with the academic acuity I considered my stock and trade.

“Pretty nice,” I added.

“Try it again,” the man said, hooking his thumbs through the belt loops of his blue jeans as if he was planning to stay awhile.

“Two minutes and you can shoot that bow better’n you shoot your pistol,” he stated. “Trust me.”

He was right.

This man had owned the shop on the main drag of that town since someone decided that time could be measured by the age of a raccoon, and he once took me outside on a cool autumn morning when traffic was sparse to nonexistent and pointed to a hill. Years earlier, he whistled a bull elk to his bow up there using a cartridge casing.

Back then, the man said, there was an elk behind every tree.

“It was like calling your dog,” he said. “You know what I’m saying?”

I sent another arrow across the floor of the back room, zipping past a neoprene wader display, sacks of goose decoys and boxes of inflatable boats that could be carried with some effort to mountain lakes and used to fish hard-to-reach places. The thud meant the arrow

(Archery) is about being where you want and putting an arrow where you want it. It is about ridges and trails, quiet places that turn thunderous faster than a summer squall, and just as quickly fall eerily silent, as if all that commotion, snorting, red-eyed glaring and yodeling was dreamed.

found that red spot in the middle of the target he called sweet.

“That arrow will go right through an elk,” the man said.

He grinned and nodded his head like he was watching someone shoot a bow for the first time.

“Nock another one!”

I spent the better part of the afternoon wearing khakis and a button-front shirt sending colorful sticks with plastic feathers into a wall of foam inside the local sporting goods store when I should have been across the street in an office dripping coffee on my shoes.

After signing up for six easy payments, I walked out of the place carrying a camo-colored bow made of aluminum alloy that cost less than a set of snow tires. It had fiberglass limbs with two wheels called cams, a side-mounted quiver, and a half dozen, made-to-fit arrows with plastic fletching that may be called vanes.

What I carried was more than a feat of engineering made in a secret enclave in Lewiston, that bore an uneasy name, Sidewinder. I knew I carried the key to a future of running shoe hunts in September in the high hills, ridge-straddling after elk talk — the mews, grunts, chuckles and bugles. The future meant hours of horn watching and delicious frustration, exertion and road maps made on napkins in cafes and parking lots in the best part of the state — its small towns. That’s where you can tell an elk hunter by the smidge of face paint left on the corner of an eyelid, his or her dusty pickup truck, referred to colloquially as a “rig,” and the choice of cologne.

“Psst ... is that Golden Estrus I whiff, or Bull Fire?”

“Shhh. I call it waller juice. It’s a special blend.”

“Got any to spare?”

When late summer turns golden,

and the nights are still warm, and lumpy camper trailers start taking root along mountainous two tracks, it’s best to sneak by them really early. Slip into the hills before the log-loading machines fire up their engines and block the high roads with cut trees sorted to fit bunks of trucks that haul the wood to the mills.

Roll quietly past the hinterland hunting camps and then amble on foot sideways up a steep hill through the charcoal night, aiming your body directly at the constellation of the bear, eagle, or swan.

The stars cover the sky like sugar spilled on a tabletop. The night hike is honeyed and sweet as a thump-ripe melon.

Before the first slick of daylight makes shadows, you’ll be among elk, and their soliloquies will be yours to pluck.

All you need to know about a bow is that it’s light and fast, and its arrows have razors that drive silently and efficiently through animals big as a steer.

Gizmos, such as egg-shaped cams and silencers, shock absorbers and magnifiers may be new, but archery hasn’t changed a lot.

It’s about being where you want and putting an arrow where you want it.

It is about ridges and trails, quiet places that turn thunderous faster than a summer squall, and just as quickly fall eerily silent, as if all that commotion, snorting, red-eyed glaring and yodeling was dreamed.

It doesn’t even matter if you send an arrow out, because humping the hills with a bow and rucksack feeds memory, and provides a lot of enchantment to draw from.

Bartholdt is a communications manager at the University of Idaho and former Tribune reporter. He also is the author of “Sometime, Idaho,” a collection of short essays, and three other books. > MEMORIES FROM Page 6

Lending for every thrill seeker.

Apply online at p1fcu.org and start planning your next outdoor adventure.

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

Anna Call started pursuing mule deer when she was a sixth grader but her journey toward being a hunter is grounded in target shooting.

As a young child, Call accompanied her dad, Clint Call, and her grandfather, Ken Alexander, of Lewiston, to the gun range where they taught her to shoot and handle firearms. Call liked that target shooting afforded her the opportunity to pursue precision and to strive for self improvement.

“There’s always that little competitive edge of ‘Oh, if I’m shooting at this target.’ The first round I can be like ‘OK, I did this well and then next round, see if I can do better,’ ” she said.

Later she tagged along on family bird hunts, first as an observer and eventually as a participant.

Now 17, the senior at Clarkston High School was 11 on her first deer hunt. Call, hunting with her family, spent two weekends looking for a buck with at least three points on one side — the legal standard for the Washington game management unit they were in.

“Finally, the very last day, the second time we went out, we finally found a legal buck,” she said. “That’s always the struggle — finding one that you can actually shoot.”

They had access to a private ranch and rode four-wheelers, stopping frequently to glass the open canyon lands for mule deer.

“We found a group of does and we spotted a few bucks in there — two of them legal,” she said.

Call and her dad hiked to get in better position for a shot. The deer focused on another member of their hunting partner, allowing Call and her dad to slip into position and set up about 180 yards away.

She squeezed the trigger of her M4 carbine rifle but sent her first shot

Anna Call with the buck she shot last fall. The Clarkston High School senior has killed five bucks in six years.

“There’s always that little competitive edge of ‘Oh, if I’m shooting at this target.’ The first round I can be like ‘OK, I did this well and then next round, see if I can do better.’ ”

— Anna Call

“We had to crouch down the hill and, like, really just stay low, and it was a good hour or two of hiking down this hill hoping it doesn’t see me. I think it was probably my longest shot, if I remember correctly, and just a single shot and it went down. I was really proud of that one.”

— Anna Call, describing her favorite hunt

wide of its mark.

“Just too much adrenaline,” she said, recalling the experience.

Call steadied herself and took a second shot.

“Got it.”

She felt excited and had some “jitters” as they hiked to retrieve the animal.

She likes hunting for the mix of experiences it delivers — being at peace in the outdoors, the excitement and anticipation of looking for deer, the thrill of the pursuit when you do, and ultimately the satisfaction of achieving a goal.

“Just being like, ‘Oh, I did that. I’m responsible for it,’ you know, the accomplishment.”

Every hunt is its own adventure, she said. She has gotten her buck on the first day of the season and the last. Sometimes it’s easy but that is not the norm.

“They’ve always had a little bit of adventure,” she said.

She remembers her third year as her favorite.

“It wasn’t my biggest one but that one definitely –– we had to crouch down the hill and, like, really just stay low, and it was a good hour or two of hiking down this hill hoping it doesn’t see me,” she said. “I think it was probably my longest shot, if I remember correctly, and just a single shot and it went down. I was really proud of that one.”

She’s taken five bucks in six years. But this fall might mark her last deer hunt for a while. Call is off to Washington State University next year and expects to be busy pursuing a degree in mechanical engineering and likely working a part-time job. But her schedule is already hectic. She participates in Clarkston High School’s drama program and works several nights a week at Fazzari’s Pizza.

“That takes up a good amount of my weekends.”

Barker may be contacted atebarker@ lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273. Follow him on Twitter @ezebarker. > ADVENTURE FROM Page 8

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

Hunting changed Jeff Benda’s perspective.

Like a lot of kids who grow up in North Dakota, he dreamed of leaving. And he did for a time, moving first to Minnesota and then to Florida to work in restaurants.

But Benda returned home for school. While wrapping up an education degree and making plans to move to Tampa, Fla., for his first teaching job, a couple of classmates invited him on a duck hunt. Soon after they took him pheasant hunting and then on his first deer hunt.

He said it was like the beginning of “The Wizard of Oz” where the world is black and white until Dorothy and Toto are swept away by a tornado and dropped in Oz.

“That is how I saw North Dakota growing up. It was just this bland black and white,” he said. “As soon as I went on my first hunt, North Dakota became color for me, just like when Dorothy stepped out into Oz and everything turned to color. I saw North Dakota differently and just fell in love with it.”

Benda hunted every chance he could. For work, he took what he calls a regular job and used his restaurant experience to open a catering side hustle. One day his wife challenged him to put a finer touch on the wild game dishes he prepared for her and their daughter.

“Make it like something you would serve at a catered event,” she said.

He accepted and moved away from chucking pheasants in a crockpot with a can of cream of mushroom

Website wildgameandfish.com

Instagram @wildgameandfish

soup and turning much of his deer into sausage. Soon he was researching recipes and creating his own. He followed wild game chef Hank Shaw on Facebook and posted recipes to Shaw’s Facebook group.

Justin Townsend of Harvesting Nature published one of his creations on his website. Benda started submitting recipes to Game and Fish Magazine and appeared as a guest on Townsend’s podcast.

While driving from Bismarck to Fargo, Benda’s wife suggested it would be neat if he could figure out

Pinterest pinterest.com/ wildgameandfishchef/ Twitter WildGameFish1 > See COOKING, Page 11

Benda is highlighting two of his recipes with Lewiston Tribune Outdoors.

Because of its long winters, Benda said the soup season last about six months in North Dakota.

“The favorite thing for my wife and daughter to do is have me pour the soup in a coffee mug and they just sit there and clench it and smell it and just savor the warmth that exudes from the cup for a few minutes before they dive in and taste it.”

Benda came up with this recipe while he and his family were snowed in at his brother-in-law and sister-in-law’s house in Bismarck. He was returning from a hunting trip and had mule deer in his cooler as well as a possession limit of grouse.

“A blizzard hit and we were stuck there for three days,” he said. “My sister-in-law had carrots and onions, celery, garlic and thyme in the fridge, and in the pantry she had a bag of wild rice.”

A neighbor had plowed their driveway and they invited him and his wife over for dinner.

“Everyone had thirds, so I knew it was a good recipe — man, woman and child had thirds.”

You can find it at wildgameandfish.com/ grouse-wild-rice-soup/

> COOKING FROM Page 10

a way to do the wild game cooking thing full time.

“I heard my wife say, ‘You should quit your job and go hunting and fishing all the time and cook wild game,’ so I did,” he said.

Now Benda runs wildgame andfish.com and has carved out his own unique space in the hook-andbullet culinary world. In addition to the website, he teaches online wild game cooking classes that were

A lot of hunters save the backstrap and tenderloins of deer and elk for steaks and use the rest for burger, jerky and sausage. When he butchers for clients, Benda preaches the virtues of sparing more meat from the grinder.

“They end up with bottom round, top round and eye of round steaks in addition to their loin,” he said.

When aged, tenderized and cooked properly on a cast iron skillet, Benda said both backstrap and loins and what some see as lesser cuts are as tasty as any served in a fine steakhouse.

“Whether it’s elk, antelope, whitetail or mule deer, if they age it, tenderize with a Jaccard (meat tenderizer bit.ly/45PucTU) and cook it to medium rare and then let it rest, they will have a completely different experience and you don’t need to marinate it or anything like that. It can be as simple as salt and pepper and it will blow their minds.”

You can find the recipe, cooking instructions and information about Jaccard tenderizers at wildgameandfish.com/ cast-iron-venison-steak/

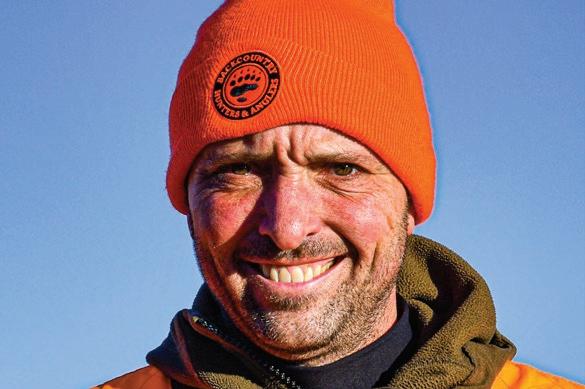

fantastically popular during the pandemic. He is a frequent guest speaker and guest chef at a wide range of events, including the national Backcountry Hunters and Anglers annual Rendezvous. He runs the Wild Game Wednesday blog for Outdoor Edge Knives. And he hires out as cook, butcher and photographer for hunting parties.

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@ lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273. Follow him on Twitter @ezebarker.

There are few equals to a properly aged, tenderized,

and rested deer, elk or antelope steak. ABOVE: Grouse and

can help keep you warm during cold winter nights.

Parasite causing reproductive problems in wild, domestic populations in Hells Canyon region

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

Wild sheep managers in the Hells Canyon region are researching a malady that causes ewes to to abort lambs and suffer miscarriages.

The Idaho Fish and Game Commission recently awarded a $5,250 grant to test archived blood samples of bighorn sheep for the presence of the parasite toxoplasma gondii that causes reproductive problems in both wild and domestic sheep. Those infected with the parasite can absorb or abort their fetuses, have stillbirths or give birth to live but weak lambs that don’t survive.

“When they get infected and for the first year after infection, they tend to lose their lambs to miscarriage or abortion, and then usually domestic sheep get over it,” said Frances Cassirer, a wild sheep researcher for the Idaho Department of Fish and Game and Washington State University. “They never get rid of the toxoplasma gondii, but their bodies get over it.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the parasite affects some 40 million Americans and most warm-blooded animals are susceptible to it. Most people with it have no symptoms of toxoplasmosis but it can cause problems with women who are pregnant and people with compromised immune systems.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, domestic sheep become infected by ingesting cysts excreted in cat feces.

Researchers at Washington State University and the Washington Animal Disease Diagnostic established that toxoplasmosis can cause pregnancy loss in bighorn sheep.

“We have seen toxoplasma as a cause of fetal and neonate loss pretty commonly in domestic sheep, but we hadn’t seen pregnancy loss due to toxoplasmosis yet in bighorn sheep,” said Elis Fisk, an anatomic pathology resident and doctoral student in WSU’s veterinary microbiology and pathology department told the WSU Insider. “Unfortunately, it does

A ewe and her lamb stand on a rock outcropping. An Idaho Department of Fish and Game grant will help fund research into a disease that causes sheep to suffer miscarriages.

“We have seen toxoplasma as a cause of fetal and neonate loss pretty commonly in domestic sheep, but we hadn’t seen pregnancy loss due to toxoplasmosis yet in bighorn sheep. Unfortunately, it does appear to be causing abortions and some level of death in young bighorn lambs.”

— Elis Fisk, anatomic pathology resident and doctoral student at WSU

appear to be causing abortions and some level of death in young bighorn lambs.”

Fisk led a study published in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases that showed the parasite has led to pregnancy loss.

Cassirer said a survey of sheep in Asotin Creek showed wide exposure to the parasite. The grant will help

determine how prevalent it is in other populations.

“We are going to use banked serum from all these captures we have done throughout the state and look for presence of exposure and see if there are any regional differences and any factors that might be associated with higher or lower prevalence,” she told the Tribune.

For example, Cassirer would like to know if it is more or less prevalent in sheep that occupy remote wilderness areas compared to sheep closer to human populations.

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@ lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273. Follow him on Twitter @ezebarker.

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

Ask anyone who regularly visits the lower Salmon River gorge or the Snake River in Hells Canyon and they may well tell you this — it’s a good year for chukars.

There are no agency surveys grounded in science indicating that. Instead, it’s all anecdotal. But there is a great deal of alignment in those anecdotal reports.

“We don’t have true numbers, just observations from people in the field,” said J.J. Teare, regional supervisor for the Idaho Department of Fish and Game at Lewiston. “It seems like broods are very large. Hopefully that will extend to lots of birds this year.”

Teare pointed out it’s common to see lots of chukars along the water in July and August. Many upland creeks, springs and seeps in the arid canyons have gone dry by mid-summer. So the birds spend more time on the rivers. Because they are so concentrated, it can make it look like populations are up.

“It’s not how many birds we see, it’s how big the broods are, and we are seeing eight to 10 chicks per adult, and that is really big,” he said. “They are about three-quarters grown now. It’s all first-clutch stuff.”

Teare said citizen reports on quail seem to indicate they are doing well this year. Eric Crawford, a former conservation officer who now works for Trout Unlimited, said he has seen healthy numbers of gray partridge, or huns, on the Palouse.

Upland populations can undergo wild swings often dictated by winter and spring weather.

Winter, of course, is the toughest time of year for most species. The weather is harsh and food is scarce. But for newly hatched ground-nesting birds, spring can be a killer. A spate of wet and cold temperatures just after birds hatch can be deadly. But neither was the case this year.

“Winter was mild. Spring was pretty easy,” Teare said.

Jana Ashling, regional wildlife manager for the department at Lewiston, said the agency is changing the way it keeps tabs on upland bird populations. For years, biologists and wildlife technicians conducted brood survey routes in which they would

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@ lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273. Follow him on Twitter @ezebarker. No official surveys are conducted, but anecdotal

drive along farm roads just after dawn and count the number of birds they observed.

The agency built an annual report based on the surveys but frequently told hunters to take the information with a grain of salt. The survey technique was developed in the Midwest and was prefaced on birds leaving farm fields in the morning to shake off dew. Ashling said the dry north central Idaho climate doesn’t really produce enough dew to reliably drive birds to seek open areas such as roads.

So the department is discontinuing the surveys and is hoping to develop an affordable and reliable way to survey chukar numbers instead. Some years ago, they used helicopters to count chukars. However, that technique was expensive, dangerous and relied on helicopter availability at a time of year they are often in high demand for firefighting. Biologists are working to develop a new method.

“It’s going to probably take a couple of years to get that really figured out,” Ashling said.

So anecdotal reports will have to do for a while.

numbers are plentiful in the Snake and Salmon river

according to anecdotal reports.

A hunter poses with a large whitetail buck he harvested.

Idaho Fish and Game

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

Managing whitetail deer requires choosing between a series of tradeoffs.

Should populations be fostered to grow to high levels? Doing so provides better odds for hunters but can also increase the risk of fast-spreading diseases like epizootic hemorrhagic disease — which can cause dramatic declines in deer numbers. Should seasons be long and allow hunting during the rut? Or should they be shorter and end before the rut? Long seasons provide more opportunity and increase the odds hunters can take a buck. But shorter seasons that exclude the rut can lead to higher buck survival and more mature bucks in the population, even

Idaho officials looking for right balance between longer hunting seasons and more deer taken, and shorter seasons and bigger bucks

if they are harder to kill.

Should buck hunting be restricted through controlled hunts or by minimum point requirements? Doing so can increase the number of mature bucks in the population but it also limits harvest opportunity.

The trade-offs go on and on and can be hotly debated in the hunting public.

What’s a manager to do?

The Idaho Department of Fish and Game has generally trended toward allowing more whitetail hunting opportunities versus managing for more mature bucks, said Jana Ashling, wildlife manager for the Idaho Department of Fish and Game at Lewiston. It also strives for what she calls moderate populations.

“We’ve seen from our public opinion surveys that folks like the ability

to go out and hunt deer every year. And in order to kind of manage for what’s considered a trophy, you have to take back a significant amount of opportunity in order to provide that, and sometimes it’s questionable whether you’d get there.”

But there are folks who advocate management designed to increase the number of mature bucks and the number of deer overall. The Fish and Game Commission shortened the hunting season in Unit 10A in 2018. Ashling said so far that has not resulted in more five-point bucks harvested.

The density of deer populations, which can fluctuate dramatically in response to disease and harsh winters, is largely managed through

A University of Idaho graduate student specializing in hatchery trout vaccination will be the guest speaker at the Kelly Creek Flycasters meeting at the Hells Canyon Grand Hotel in Lewiston on Thursday.

Veronica Myrsell will deliver “Developing improved vaccination strategies to prevent furunculosis in rainbow trout and sablefish.” Myrsell received a scholarship from the fly fishing organization.

A social hour starts at 5:30 p.m.

> WHITETAIL FROM Page 14

doe harvest, said Kenny Randall, a regional wildlife biologist for the department at Lewiston.

If the population is deemed too low, managers can restrict the harvest of does to build it back up. If the population is too high, they can increase doe hunting opportunities.

“When considering adding or removing antlerless harvest, we assess the primary constraints and factors influencing deer populations at various levels,” he said. “This includes factors such as disease management and reducing the risk of outbreaks, how to help populations rebound or grow in areas that have seen decreases in harvest metrics, and when and where populations are associated with agricultural depredations.”

Those harvest metrics Randall mentioned are the primary way Fish and Game monitors whitetails. Unlike elk and mule deer that often occupy open country during the snowy months, whitetail deer are difficult to count during aerial surveys. They are masters at using cover and habitat to hide from predators, including people. They like forests and brushy canyons where cover is ample. While they do venture into open fields, they tend to choose fields edged by forests or other cover where they can retreat from perceived dangers, such as the sound of a helicopter.

“We’ve tried different survey methods,” Ashling said. “It’s just incredibly difficult with whitetail.”

So the agency relies on hunter harvest reports as a surrogate to population counts. They track things like hunter participation, how many bucks are harvested and how many of those bucks have five points or more on one side. Those metrics are applied differently across three broad habitat types in the Clearwater Region – though those areas, known

A no-host dinner will be served at 6 p.m. and be followed by the presentation from Myrsell.

COEUR D’ALENE — Private property owned by the North Idaho Timber Group and enrolled in the Idaho Department of Fish and Games Large Tracts Program have reopened to public access.

The lands, all in the Idaho Panhandle, had been closed because of high fire danger. According to an Idaho

as data analysis units, or DAUs, spill outside of the region’s boundary. There is the northern agriculture DAU, which is largely the Palouse farming region and where it meets the forested foothills of the Bitterroot Mountains — hunting units 5, 8, 8A, 10A, 11, 11A and 13. The central forest DAU is made up of units 7, 9,10, 12, 14, 15, 16, 18, 23, 24. The backcountry DAU includes 16A, 17, 19, 19A, 20, 20A, 26 and 27.

The northern agriculture is the region’s prime whitetail habitat and has the highest concentration of hunters.

The department aims for a minimum of 18,000 hunters, 130,900 hunter days, the harvest of 5,200 bucks and with at least 17% of those being fivepoint or better bucks. The three-year average in 2019 to 2021 saw about 17,000 hunters, 143,779 hunter days, nearly 5,100 bucks killed and a fivepoint or better average of 23%. Those numbers are down compared to the 2016-2018 average, but Randall said they are climbing.

Many of the area’s deer herds, especially those at lower elevations, were hit hard by an EHD breakout in 2021.

“In terms of harvest metrics, we’re pretty close to that threshold that we’re looking for basically across the board in all of those DAU in terms of buck harvest,” he said.

Ashling said following the 2021 die-off of thousands of whitetail, the department eliminated extra doe tags in unit 11A, the hardest hit, and reduced extra doe tags in other areas. Following a previous die-off, she said it took the hardest hit areas about five years to recover.

“So they are able to recover pretty quickly,” she said. “They are very adaptable.”

The state’s whitetail deer management plan runs through 2025. When that plan begins to near the end of its lifecycle, Fish and Game officials will

Fish and Game news release, recent rain has reduced the threat of accidental fires.

Idaho hunter education class offered in early October at Lewiston

An accelerated hunter education class will be offered at the Idaho Fish and Game regional office in Lewiston Oct. 5-7.

The 12-hour class includes classroom and field sessions, and will be taught by three experienced instructors — Gerald Bateman, Jill Green

start working on an update and ask the public for ideas.

“What we’ve heard from a portion of the public is there is a desire to change whitetail management,” Ashling said. “The best way to look at how to do that is to go out with a survey and make sure we reach out to folks and kind of see what they really do want.”

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@ lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273. Follow him on Twitter @ezebarker.

and Steve Hanson. The classroom sessions will be held from 5-8 p.m. Oct. 5 and 6. The field session will be held from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Oct. 7.

Students must read the book “Today’s Hunter in Idaho” and complete the written exercises in it prior to the class. The book is available at Fish and Game offices.

Those interested in the class can sign up at bit.ly/3qYBR3v.

SPOKANE — The eastern region of the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Washington chapter of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers are teaming up to encourage hunters to have their deer and elk tested for chronic wasting disease.

Hunters who voluntarily submit their animals for testing will be entered into a drawing for one of 100 multi-season deer tags. Backcountry Hunters and Anglers helped pay for the tags. More information is available at bit.ly/44zEjLu.

By SAMMY FRETWELL THE STATE

When a laboratory confirmed that a lethal wildlife disease had been found in South Carolina, the finding sent chills through biologists at the state Department of Natural Resources.

The DNR has tried for years to keep chronic wasting disease out of South Carolina in an effort to prevent it from spreading to native whitetailed deer populations. But those efforts, which rely on educational programs and state restrictions, were not enough to stop several hunters from hauling in parts of a deer that was killed in Kansas, wildlife officials say.

A deer head, imported in 2019 for display as a trophy, contained chronic wasting disease, an ailment likened to “mad cow’’ disease in deer. The discovery was the first — and only — time the disease has been verified in a deer transported into South Carolina, a DNR official said.

Now, three South Carolina men face federal wildlife charges, in this case involving the importation of a deer part from a state where chronic wasting disease has been found in the wild.

Sean Robert Paschall, Chad Caldwell Seymore and Justin Grady LeMaster were recently in court in Columbia. Seymore faces two federal counts of unlawfully transporting wildlife, while Paschall and LeMaster face one count. A U.S. district judge in Columbia set bond at $20,000 apiece. If convicted, the men face could face up to five years in prison.

“This particular case demonstrates why we have regulations prohibiting these carcass parts from being imported from states’’ where chronic wasting disease has been found, said Charles Ruth, a state wildlife department official whose agency worked with the U.S. Attorney’s office.

Ruth said South Carolina is lucky because wildlife officials found the diseased deer head before the affliction spread into the wild. But the state needs to remain vigilant, he said, noting that there could be cases where diseased deer parts are smuggled into South Carolina.

Chronic wasting disease is an illness that afflicts deer, elk and related species. It has not proven to be fatal to humans, although a recent study in Canada indicated there could be some risk. But the disease can have real impacts over time on deer

populations that hunters rely on for harvest.

Infected deer become listless, lose weight and hair, begin to drool and stagger around. Chronic wasting disease is almost always fatal to deer and can spread easily among deer populations. It was discovered in 1967.

According to a federal indictment, the South Carolina hunters broke state big-game and wildlife possession laws in Kansas. Then, in South

Carolina, they possessed deer parts from another state where chronic wasting disease has been identified, also a violation of state law, the indictment says.

The interstate movement of deer constituted federal violations. If someone breaks a state law in obtaining fish or wildlife, it is a violation of federal law to transport animal parts to another state.

The hunters declined comment after their arraignment in Columbia. The U.S. Attorney’s Office would not provide the ages and hometowns of the hunters who face charges, other than to say two are from the Upstate and one is from the Columbia area.

Seymore’s lawyer, James Brehm, said his client is a 48-year-old Green-

Authorities seized deer antlers from Paschall’s son and brother, who is now deceased, as well as from Seymore, records show.

By JOHN MYERS DULUTH NEWS TRIBUNE, MINN.

WASHINGTON D.C. — The annual survey of waterfowl across prime North American breeding regions tallied 32.3 million ducks this year, down 7% from 2022 and down 9% from the long-term average.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service released its 2023 Waterfowl Population Status report recently based on surveys conducted in May and early June with help from the Canadian Wildlife Service and other natural resource agencies.

The survey also found the number of small wetlands, or ponds, down 9% from last year and 5% below the longterm average.

Biologists use the annual survey to track waterfowl trends and to set parameters for the fall hunting seasons.

Mallards, the most common and

ville County resident.

Brehm told The State that the men went hunting in Kansas, lured by the big deer found there, but “just had no idea’’ about South Carolina rules against importing deer from a state where chronic wasting disease has been found. Brehm said the men found it was more expensive to process deer in Kansas than in South Carolina.

Chronic wasting disease has been detected in the wild in about 30 states, including in Kansas and parts of the West. But some eastern states, including North Carolina, Virginia and Pennsylvania, have discovered the affliction in free-ranging deer, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Deer hunting is considered the single-biggest hunting activity in South Carolina, pumping millions of dollars into the economy each year. The economy could be hurt either by a hesitancy from sportsmen to hunt diseased deer or in actual population declines from the deaths of sick deer. All told, the state’s deer population exceeds 700,000 animals, a 2019

commonly hunted duck, were down 18% from 2022 and 23% below the long-term average.

While the survey was taken before this year’s ducks were hatched, officials said the decline shows habitat continues to play the key role in waterfowl populations.

“These results are somewhat disappointing, as we had hoped for better production from the prairies following improved moisture conditions in spring of 2022,” said Steve Adair, chief biologist for the conservation group Ducks Unlimited.

Severe drought across parts of Canada’s prime nesting areas could cause duck numbers to slip even more.

The Minnesota DNR reported earlier this month that its spring survey showed duck numbers down 22% from 2022 and 15% below the longterm average. North Dakota report-

DNR study says. That’s substantially more than other popular game species, including hogs and wild turkeys.

Chronic wasting disease was suspected as a major contributor to a 45% decline in deer abundance near Boulder, Colo., from 1988-2006, according to a 2016 study by a team of scientists. In Wisconsin, spending on deer hunting declined, at one point, by at least $48 million, in part because of chronic wasting disease, another study shows.

South Carolina, like other states, has adopted laws against importing certain deer parts that could contain chronic wasting disease, such as the head.

Hunters who kill deer in other parts of the country must have the heads processed in the states where the animals were shot, if those states have had chronic wasting disease outbreaks, according to South Carolina law. They then can bring a mounted deer head back to South Carolina. In addition to laws, the state also has spent considerable time trying to educate hunters about the dangers of bringing in animal carcasses that could spread disease. But Ruth and

Duck hunters will have fewer targets this fall, according to annual waterfowl surveys. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reports duck populations are down 7% compared to last year.

ed a slight increase in overall duck numbers compared to 2022, although mallard numbers were down 10%.

Frank Rohwer, president of the group Delta Waterfowl, said the production of new ducks this summer should have been good in some areas,

federal prosecutors concede the educational effort is not foolproof.

South Carolina’s native whitetailed deer population is fairly robust, although numbers have dropped somewhat in the past two decades. At one point more than 50 years ago, deer were not nearly as common in South Carolina, the result of over

including parts of North Dakota that had ample wetlands, which may help make up for the spring decline.

“I think duck production is going to be a much better picture than what we’re seeing in these survey numbers,” Rohwer said.

harvesting, habitat loss and a lack of laws protecting the animals.

South Carolina’s deer hunting season has opened in parts of the state, with the rest of the state to be open by early October.

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

The first hunts always happen in the shoulder season between summer and fall.

That means mild temperatures, which is good for those who like to hunt in lightweight clothing. But it can be disastrous if you get an animal down just as temperatures are climbing and you aren’t prepared to care for the meat.

Here are some tips from the Idaho Department of Fish and Game to help keep meat from spoiling.

According to a news release from the agency, when temperatures are high, hunters should quickly act to preserve meat. That means immediately skinning and quartering the animal, then getting it to cold storage as soon as possible.

“The primary thing for the care of game is to get the hide off the critter as soon as you can,” Mark Carson, a now-retired conservation supervisor for the department, told the Tribune in 2017. “The function of all hides are to keep the animal warm, and it works just as effectively when they are dead.”

Carcasses that are not cooled properly can become “bone sour.” According to the news release, that happens when high temperatures produce explosive bacterial growth near bones and joints. The result is meat with a foul taste that can’t be mitigated.

Ice it

Sliding bags of ice in the body cavity of an animal can help keep meat from spoiling. However, the agency warns not to depend on ice. Animals should still be skinned and quartered and lifted off the ground. Both skin and the ground serve as insulation that traps heat and spoils meat.

Hanging meat helps but can not always be relied on. If it’s too warm, hanging meat can still spoil. In these conditions, have ice on hand and get meat to a cool place, such as a meat locker, as soon as possible.

It’s best to have a game plan in place prior to the hunt. In hot weather, have or know of a nearby ice source and know where you will take

your meat once you leave the field. Carson said many hunters freeze water in milk jugs prior to warm weather hunts and then place them in the cavities of downed animals or use them to chill coolers.

He said if you place quartered meat in a cooler, leave the top cracked during the first 24 hours so heat can escape.

No fly zone

Warm weather means bugs like flies will be out. Be prepared with game bags that keep bugs from laying eggs in your meat. Game bags also deliver an added benefit — they help keep skinned meat clean. Clean, cool water

Water may be used to clean a

skinned carcass. However, the agency recommends using clean water and making sure the meat is able to dry quickly. Water can prompt growth of bacteria. So avoid placing skinned meat places where it will be in prolonged contact with water, such as a cooler with free-floating ice.

Winter spoil

Don’t be fooled by cool weather. Carson told the Tribune that conservation officers often write wasting citations when the ground is blanketed with snow. The cool temperatures sometimes lead hunters to believe there is no threat of spoilage. Not so. Again, Carson stresses that hides are designed to retain heat. On top of that, snow can be insulating as well.

“An unskinned elk lying on its side has snow and multiple layers of skin between the outside of its shoulders and hams and the meat,” he said. At the very least, the animal should be lifted off the ground. Even using logs or rocks to get a few inches of clearance can make a difference, he said.

“That will buy you some time,” he said. “I like it to be laying on its backbone with the body cavity open so heat can escape and the legs splayed out so you don’t have four layers of hide on each side of the armpits.”

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@ lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273. Follow him on Twitter @ezebarker.

Average winter in Clearwater Region means no survival red flags; whitetail deer numbers up slightly

By ERIC BARKER OF THE TRIBUNE

Idaho Fish and Game officials expect this fall to be on par with recent years in terms of the health and availability of big game herds.

The Clearwater Region was largely spared the long and harsh winter with deep snow that hit the southeastern portion of the state. That means elk and deer survival should have been average or better in the region, so no red flags there.

Elk

The distribution of elk herds in the Clearwater Region and their health is not expected to be different from recent years. That means low densities in the Lolo, Selway and Hells Canyon zones, according to an Idaho Fish and Game hunting season preview report. Elk in those areas, especially the Lolo and Selway zones, have struggled for more than 20 years. The culprits are declining habitat because of forest succession and abundant numbers of predators including wolves, mountain lions and black bears. However, the agency hinted at some positive news — observations of elk calves are up slightly and elk can be found in abundance in some areas.

The Palouse Zone remains an area where elk are stable. According to the agency’s hunting report, elk numbers, hunter success rates and hunter numbers are stable there.

Elk abundance has been down in the Dworshak Zone for 10 years or so but the agency reports harvest rates are stable. Elk numbers are strong in the Elk City Zone, especially in Unit 14. But, according to the department, abundance is sliding in units 15 and 16.

The agency continues to monitor

the spread of elk hoof rot, officially known as treponeme-associated hoof disease. The disease causes lesions on elks’ hooves that can progress to abnormal growths. It is not always fatal, but impairs afflicted elk, making it harder for them to move, find food and escape predators. It has been spreading westward from western Washington and was first found in Idaho in 2019.

Idaho Fish and Game officials are asking hunters to report elk with abnormal hooves or elk that are limping or lame. Hunters are asked to submit the hooves of harvested animals if they show signs of the disease.

Whitetail deer

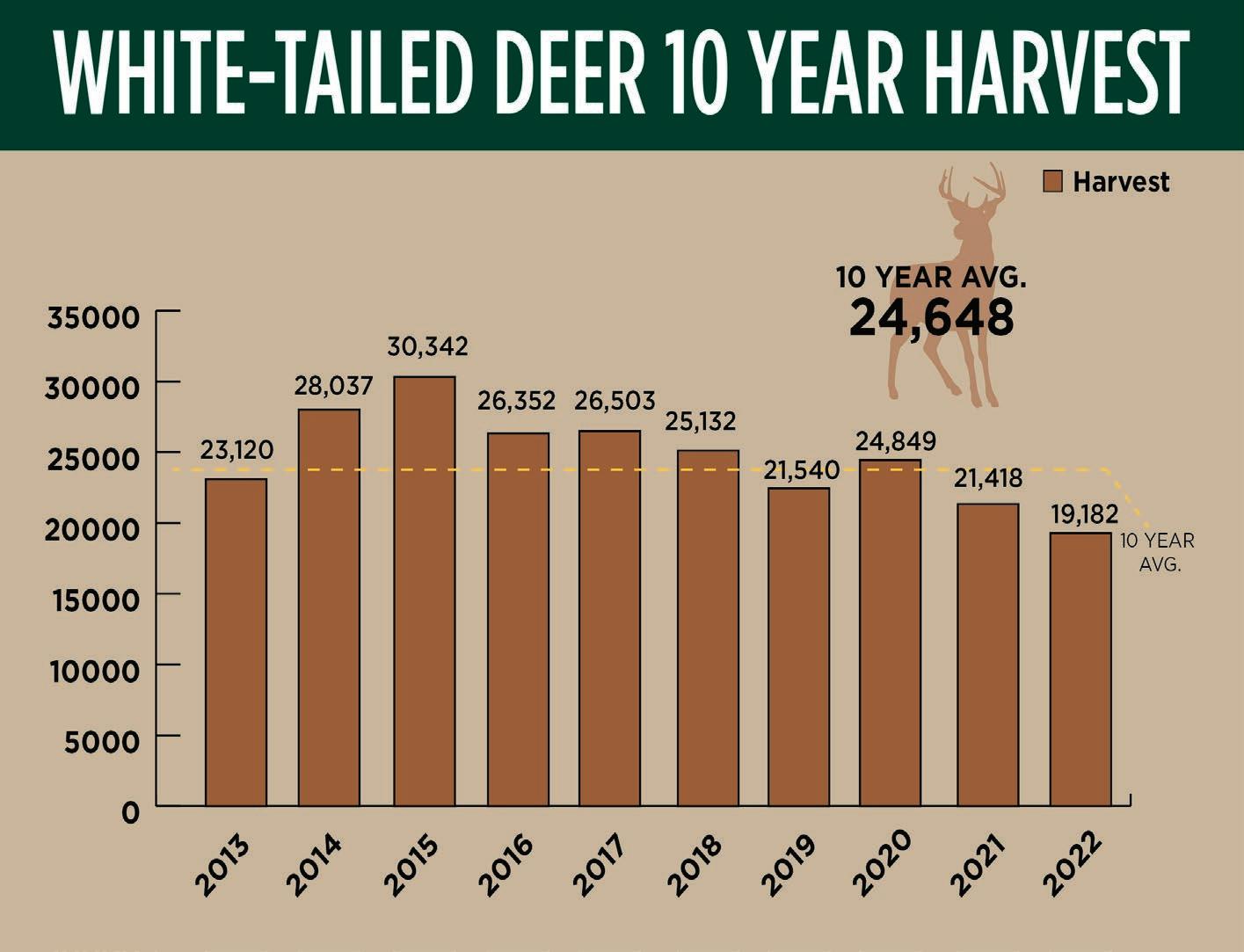

Whitetail deer numbers are slowly rebounding following a crash in 2021 — the result of a widespread outbreak of epizootic hemorrhagic disease that killed many thousands of animals. It was especially prevalent in lower elevation areas. Whitetail harvest across the state was 21% off the 10-year average. So far this year, large outbreaks of EHD have not been detected in the region.

Chronic wasting disease remains a concern in Unit 14. Last winter and spring, Idaho Department of Fish and Game officials culled more than 400 deer near Slate Creek to help reduce the spread of the fatal disease. Testing of those animals revealed a prevalence rate of about 5%.

Units 14 and 15 are in a CWD Management Zone where successful deer, elk and moose hunters, must submit samples for CWD testing. More information about the disease and the state’s response to it are available at dfg.idaho.gov/cwd.

Barker may be contacted at ebarker@ lmtribune.com or at (208) 848-2273.