6 minute read

Water Resources

Watersheds

Lexington contains 21 sub-watersheds (also called drainage basins) that drain to three major watersheds, the Shawsheen River Watershed, the Mystic River Watershed, and the Charles River Watershed, which meet on Eliot Road near the Community Center. Major storage basins exist at Tophet Swamp for the Shawsheen River Watershed, Dunback Meadow and the old Metropolitan State Hospital area (and to a lesser degree, parts of Hayden Woods) for the Charles River Watershed, and the Great Meadow and Munroe Meadows for the Mystic River Watershed. The boundaries of major watersheds are shown on MAP 6. Map 6A Subwatersheds depicts the Town’s sub-watersheds and was prepared by David Pavlik of the Town’s Engineering Division in March 2008. Note that the Shawsheen River Watershed is a drainage area without a major stream channel, which accounts for the difference between the Town’s 20 brooks and 21 subwatersheds. Lexington’s sub-watersheds include:

Draining to the Shawsheen River Watershed

Draining to the Mystic River Watershed

Draining to the Charles River Watershed

• Farley Brook • Kiln Brook • North Lexington Brook • Simonds Brook • Turning Mill Brook • Vine Brook • Willards Brook • Shawsheen River Shed • Fessenden Brook • Mill Brook • Munroe Brook • Reeds Brook • Sickle Brook • Shaker Glen Brook • Winning’s Farm Brook • Beaver Brook • Chester Brook • Clematis Brook • Hardy’s Pond Brook • Hobbs Brook • Juniper Hill Brook

Surface Water

While Lexington does not have a major river running through its landscape, it does have 20 brooks that play important roles in the infrastructure and character of the town. All of Lexington’s brooks originate within the Town’s boundaries and flow outward to other towns except for a small section of Reeds Brook, making Lexington a headwaters community. Over time, these brooks have been altered by human activity through changes such as channelization, the introduction of culverts, and sedimentation build-up from road sand and other run-off. Furthermore, impervious surfaces such as roads, parking lots, and buildings have caused more stormwater runoff to enter the brooks than would naturally. These impacts have resulted in flooding problems, degradation of water quality, and impacts to habitat in many areas. Lexington’s brooks flow directly into Arlington, Belmont, Waltham, Lincoln, Bedford, Burlington, and Woburn before traveling onward to discharge in the Atlantic Ocean near Boston and Newburyport. The Town’s brooks contribute to water supplies in Burlington via the Vine Brook, Bedford via the Kiln Brook/Shawsheen River, and Woburn via Woburn’s Horn Pond from Shaker Glen Brook, as well as Cambridge via Hobbs Brook and the Cambridge Reservoir. The other two reservoirs in town, the Arlington Reservoir and the Lexington Old Reservoir (or Old Res), are now used for swimming rather than water supply.

In 2007, the Louis Berger Group, Inc. completed a water quality study of the Old Res, which has had problems with high coliform counts after rainstorms. A deepwater well was added in 1982, which serves to maintain the water level but does not guarantee improved water quality. The results of the study show that the major source for bacteria entering the water body is stormwater discharged by the four outfalls along Marrett Road. In addition to providing a popular swimming area in Lexington, the water from the Old Res eventually flows to the Vine Brook and on to the Shawsheen River watershed, so improving water quality is also important to communities downstream. In 2009, Town Meeting appropriated Community Preservation Act (CPA) funding to complete a stormwater management mitigation project at the Old Reservoir which was completed and implemented in 2013. Other issues with brook health and function in Lexington are being addressed through a Watershed Stewardship Program that started in the fall of 2008. The program, initially coordinated by the Conservation Division, the Engineering Division, and citizen volunteers, including the Lexington Conservation Stewards and students from the Minuteman Career and Technical High School, conducted stream shoreline surveys to identify problems caused by stormwater run-off and impaired outfalls. The data collected in those surveys was processed into map format and used as a planning tool for remediation of identified stream problems. The program is now coordinated solely by the Engineering Division and engages students from the University of Massachusetts Lowell through an internship program. Efforts to mark storm drains with “Don’t Dump, Drains to Stream” markers began in 2011 and are ongoing, through the Engineering Division in collaboration with the Conservation Stewards.

Functions of Lexington’s Brooks

Lexington’s network of small brooks and the wetlands surrounding them serve as the backbone for the Town’s hydrology, and provide the following functions: Hydrologic: • Brooks provide avenues for stormwater to travel in, acting as efficient conduits for moving water and help to reduce flooding. • Brooks help maintain a stable groundwater “budget” by transferring excess water during seasonally high groundwater periods, thereby reducing flooding. • Brooks act to recharge groundwater supplies through infiltration. • Brooks assist in the maintaining of static water levels in ponds and reservoirs. Ecologic: • Brooks assist in filtering out pollutants and sediment, especially by discharging water into surrounding wetlands with filtration capacities. • Brooks provide prime wildlife habitat, including habitat for several threatened and endangered species. • Brooks create ecological diversity by helping to maintain the hydric (wet) soil conditions that support important wetland plant communities. • Brooks provide aesthetic enjoyment for citizens and passive recreation for hikers, fishers, bird watchers, and outdoor enthusiasts.

Value of Brook Corridors to Wildlife

Brook corridors traverse a large number of Lexington’s conservation areas. Prolific wetland systems surrounded by relatively large tracts of undisturbed land, as well as vegetated areas running along brook channels, provide essential components of wildlife habitat, including: food, cover, water, and nesting and breeding space. Some of the most important brook corridors that currently exist in Lexington include areas along Vine Brook, Simond’s Brook, Munroe Brook, Beaver Brook, and Kiln Brook. Degradation to these natural brook corridors impacts species that travel in them, such as white-tailed deer, coyote, and fisher. For a further discussion of wildlife corridors in Lexington, see the section on Fisheries and Wildlife.

Certified Vernal Pools

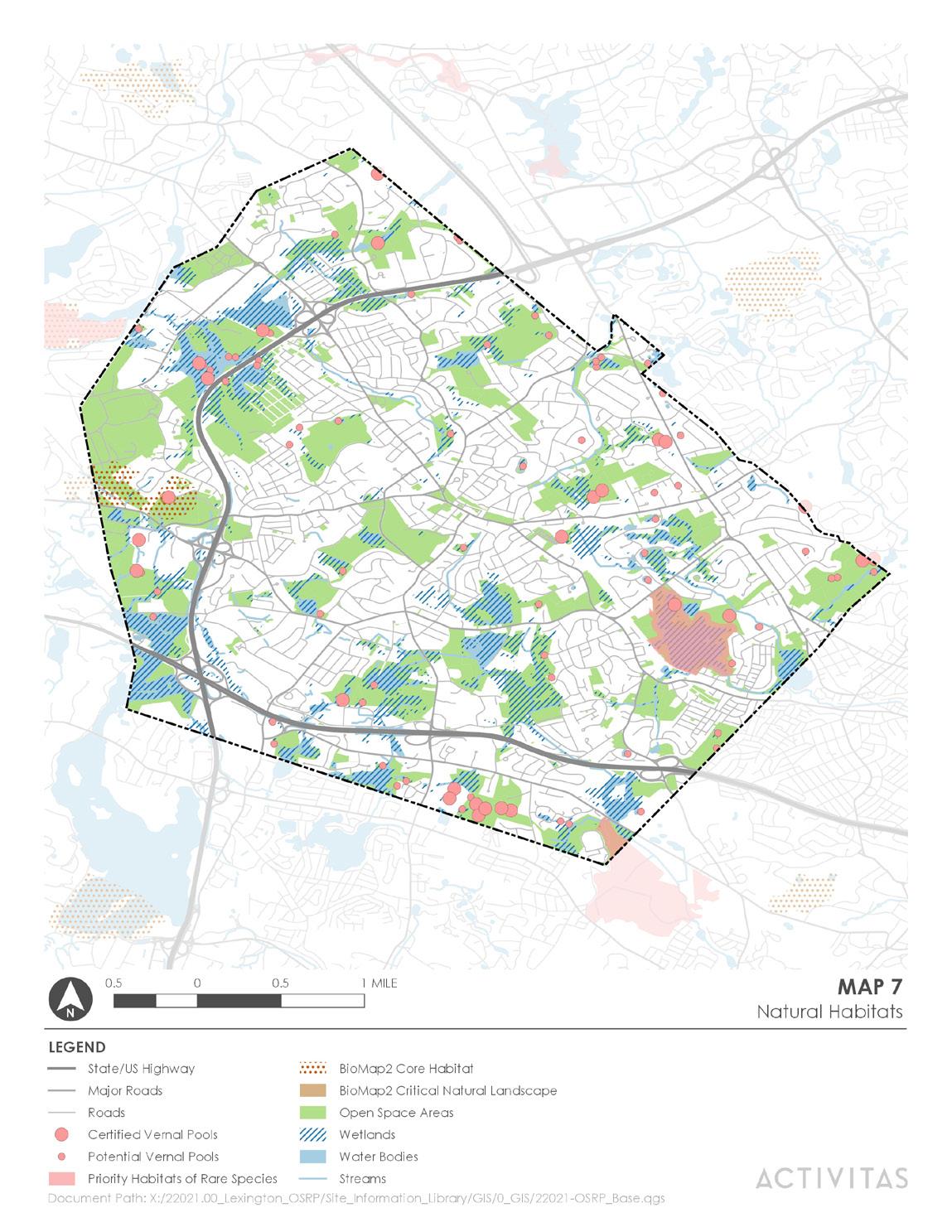

Vernal pools are ephemeral bodies of water that do not support predatory fish and provide essential spring breeding habitat for various amphibian species, including wood frogs and blue-spotted salamanders. Vernal pools are protected by the Massachusetts Wetlands Protection Act, but must be certified as vernal pools before falling under this protection. Twenty-four certified vernal pools are located within the Town of Lexington as of November 2022. The locations of cataloged vernal pools are shown on MAP 7.

Flood Hazard Areas

The boundaries of the one hundred year floodplain are shown on MAP 6. Floodplain areas in Lexington provide important temporary flood storage capacity when adjacent surface water bodies overflow. These areas frequently contain valuable wildlife habitat including a number of Lexington’s certified vernal pools.

Wetlands

The Commonwealth’s Office of Geographic and Environmental Information (MassGIS) has mapped approximately 519 acres of open marshes/bogs and 750 acres of wooded marshes in Lexington, and more freshwater wetland exist that have not yet been mapped. These freshwater wetlands provide habitat, recharge groundwater, purify water, and store surface runoff, slowing the progress of flood waters. Many of the freshwater marshes in Lexington fall within open space areas, including Tophet Swamp, the Great Meadow, Willard’s Woods, and Dunback Meadow. MassGIS’s mapped wetlands are shown on MAP 6.

Aquifer Recharge Areas

The high percentage of impermeable surface in Lexington, both natural and human-made, results in a high rate of precipitation runoff, which reduces the amount of water available for groundwater recharge. Groundwater recharge takes place in wetlands, such as those found in the Upper Vine Brook, Lower Vine Brook, Willard’s Woods, and Dunback Meadow conservation areas. Lexington includes 3,256.7 acres of Kiln Brook photographed in the Meagherville Conservation Area. Department of Environmental Protection Approved Wellhead Protection Areas (Zone II), which are important for protecting the recharge area around public water supply groundwater sources. Most of this acreage falls in the Vine Brook watershed, which provides drinking water for the town of Burlington. These Zone II areas are shown on MAP 6.