14 minute read

The Artists of New Jersey’s Golden Age of Golf Course Design

BALTUSROL AND THE U.S. OPEN: 1967 AND 1980

Nicklaus and Baltusrol—a Marriage Made in Heaven

THERE MAY BE NO BETTER WAY to determine the greatness of a course than to see which golfers triumph on its fairways. On that basis alone, Baltusrol Golf Club’s Lower Course is clearly among the elite few, for Jack Nicklaus rose to the top in its 1967 and 1980 U.S. Opens.

NEW JERSEY’S U.S. OPEN CHAMPIONSHIPS 1967, 1980

YEAR COURSE WINNER SCORE RUNNER-UP

1967 Baltusrol GC (Lower) Jack Nicklaus 275 Arnold Palmer

1980 Baltusrol GC (Lower) Jack Nicklaus 272 Isao Aoki

Nicklaus did it his way, setting U.S. Open scoring records both times. But that’s not to say he did it the easy way. The first time, he had to overcome the gallery’s palpable preferences for the King—Arnold Palmer—and, in 1980, he barely escaped the putting wizardry of Isao Aoki.

1967

ARNIE, JACK, AND WHITE FANG

This was the year Jack Nicklaus, armed with his new putter, White Fang, took on the most popular golfer of the era, Arnold Palmer. Palmer had not won a major since the 1964 Masters and was, by all accounts, overdue. He had captured two events earlier in 1967 but had notably collapsed in a duel with Billy Casper for the title at the 1966 U.S. Open at The Olympic Club. Palmer yearned for another major; it surely occurred to him that Baltusrol in June would be the place and time.

Nicklaus had designs of his own. A Wednesday practice-round match with Palmer yielded a 62, fifteen dollars as a result of their Nassau, and gave Nicklaus the confidence that Baltusrol could be conquered. White Fang, an Acushnet Bullseye putter custom-painted white then christened by Nicklaus, yielded nine 1-putt greens in that practice round and was soon to make U.S. Open headlines throughout the country.

But there were 148 other players in the event. One of them, Marty Fleckman, an amateur bomber from Texas, stole the show with a first-round 67, two ahead of Palmer and U.S. Open defender Casper. Nicklaus signed for a 1-over 71, a round he considered satisfactory.

Palmer’s second-round 68 (with seventeen greens hit in regulation) captured the lead at 137, just one ahead of Nicklaus, whose 67 featured several clutch, White Fang-produced putts. While other players—Fleckman, Casper, Deane Beman, Don January, and newcomer Lee Trevino—lurked in the shadows, to the casual fan the U.S. Open had become a “King Arnie vs. Jack the Pretender” title match. And, for Jack, it wasn’t always pleasant. Some members of the Jersey brigade of Arnie’s Army were vocal, for example, suggesting Nicklaus hit the ball into the rough. Palmer would get roars of approval for hitching his pants, while Nicklaus would often only receive polite applause for moments of brilliance. On this day, Nicklaus was having to deal with more than the course and the field. In the third round, as so often happens in anticipated head-to-head matches, both players didn’t fare well. Nicklaus’s 72 bested Arnie’s 73, leaving them both at even-par 210. However, their sloppy play allowed amateur Fleckman (69) to take the lead by one and defending champ Billy Casper (71) to join them at even par. An amateur one shot clear of three of the greatest golfers who ever lived—this was an U.S. Open leaderboard for the ages.

In the final round, Nicklaus and White Fang regained their

practice-round form. Playing with Palmer in the second-to-last pairing, Nicklaus birdied five of his first eight holes and went on to card a 65 to Palmer’s otherwise fine 69. Nicklaus posted an exclamation point on the round with a 230-yard 1-iron third shot on the par-5 18th hole to set up a birdie and a four-shot win. That 1-iron shot was commemorated by Baltusrol with a plaque on the site of Nicklaus’s divot and has been slowing down play on No. 18 fairway ever since. In the end, Nicklaus (275, -5) and Palmer (279, -1) were the only players to finish under par. Nicklaus owned a new U.S. Open scoring record. His 1967 title was the second of an eventual four U.S. Open wins and the seventh of his record career eighteen major championships. This win also had the effect of quieting most of the anti-Nicklaus chatter.

Palmer remained a huge force in the game, but never won another major championship.

OPPOSITE, CLOCKWISE FROM UPPER LEFT: The crowd shows support for Arnold Palmer; Marty Fleckman signs autographs; Nicklaus’s final-round 65 helped set a new U.S. Open record. ABOVE AND INSET: Nicklaus won the championship using a Bullseye putter painted white that he named “White Fang.” FOLLOWING PAGES: Nicklaus and Palmer were the only players to finish under par during the championship.

A CERTAIN FLAIR

Robert Trent Jones Sr. had a knack for the dramatic. As noted New York Times sports columnist Dave Anderson mentioned, Jones was fond of saying “The sun never sets on a Robert Trent Jones golf course.’’ Anderson also recalled that, “When Mr. Jones redesigned the fourth hole at the Baltusrol Golf Club’s Lower Course in Springfield, N.J., before the 1954 United States Open, some members thought the par 3 over a pond was unfair.” Jones had lengthened the hole’s original Tillinghast yardage of 125 yards to 165 yards. But he had also enlarged the green, making it more receptive to long-iron shots, thereby compensating for the new length. “He offered to play the hole along with Johnny Farrell, the club pro, and two members while other members watched. Playing from the 165-yard members tee, Mr. Farrell and the two members each hit balls on the green. Mr. Jones stepped up and swung his 4-iron. His ball landed on the green and rolled into the cup for a hole in one. Turning to the assembled members, he said: ‘Gentlemen, the hole is fair. Eminently fair.’ ”

BACKGROUND PHOTO: Not only is the fourth hole at Baltusrol (Lower), “eminently fair,” it is one of the game’s most photographed holes.

PART FOUR THE MODERN GAME SINCE 1990

As America entered the 21st century,

the popularity of golf rose and fell with movement in the economy, seemingly immune to war, politics, and climate change—even to pandemics.

Since 1990, we golfers noticed: the last professionals using persimmon drivers; Greg Norman’s penchant for losing the big one; the emergence of Augusta National Golf Club as more than just the site of a great golf tournament; Tiger Woods winning so often and so convincingly that he seems on his way to demolishing any argument about who is golf’s greatest—then seemingly blows it; the Ryder Cup become absolutely huge; the passing of the game’s most beloved general, Arnold Palmer; each of our five American presidents during this time displaying a love of golf, while playing it five different ways; a thirty-four-yard increase in the distance PGA Tour players smack their drives; and the proliferation of good greens everywhere.

We’re talking about a lot of change.

In that time, New Jersey golf evolved as well. In the space of fewer than ten years, New Jersey experienced a renaissance in golf course architecture, often facilitated by modern-day visionaries who must have been

inspired by their predecessor, Pine Valley Golf Club’s George Crump. The finest players in the state racked up impressive wins (including a national championship), but New Jersey’s best amateur since Jerry Travers tragically died early. The scribe of New Jersey golf—who had become a bit of a legend himself—died, but his decades of work have been memorialized in what has quickly become an institution in New Jersey—interclub team competitions. What may have been Baltusrol Golf Club’s last U.S. Open cleared the decks for what appears to be a new series of championships with the PGA of America. And a pro’s pro, Ed Whitman, became just the third four-time winner of the New Jersey Open.

While so much is changing, one of golf’s most basic appeals is its timelessness. The objective—to get the ball in the cup in the fewest number of strokes—hasn’t changed in centuries. The rules are, at their essence, what they were in 1900. New Jersey is blessed with clubs that place golf at their core, that strive to achieve a sense of timelessness while maintaining relevance in a fast-paced world. As you’ll see, Somerset Hills Country Club is one of those places.

“It’s déjà vu all over again!” —Yogi Berra, member, Montclair Golf Club

AN UNPRECEDENTED NUMBER of quality New Jersey courses have recently come to life at a time when more austerity might have been expected. This burst of creative brilliance is still too fresh to determine if it is as auspicious as it appears. Look back in thirty or forty years and we’ll know definitively whether a compact span of time—1998 to 2006—was New Jersey’s second Golden Age of Golf Course Architecture.

1990s

A WELL-SET TABLE

The 1990s were a special time in America—a period of growth, optimism, and great prosperity in the United States. The largely unexpected development of the internet and the explosion of technology that came with it fueled this expansive view, as did our country’s emergence in the early 1990s from the Cold War as the world’s lone superpower.

Starting in 1991, the U.S. economy experienced a record period of peacetime economic expansion. Personal income was up 20 percent from the 1990 recession to 2000 and there was higher productivity overall. Life was good, so much so the Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan applied the term “irrational exuberance” in late 1996 to the U.S. economy.

Golf benefited from these heady times. By the late 1990s, the “Tiger Effect” was starting to be felt as young Tiger Woods came into his own. In 2000, his most productive year, the highest-ever number of beginners—2.4 million—took up the game. The number

ABOVE: The “Tiger Effect,” started to build momentum with Tiger Woods’s win at the 1997 Masters Tournament. OPPOSITE: Plainfield Country Club’s 2nd hole

IN THE ONE HUNDRED-YEAR history of the New Jersey State Open, only three players—all professionals—have won the event a total of four times. Milton “Babe” Lichardus was the first quadruple winner of the most difficult contest the NJSGA has to offer, followed by David Glenz, then Ed Whitman. These gentlemen each deserve a special place in the roll call of New Jersey’s top players ever.

Lichardus won his first Open in 1952 at storied Plainfield Country Club. A Baltusrol Golf Club assistant professional at the time, this was Lichardus’s first step on his way to being named the 1950s Player of the Decade by his club professional peers and etching his name onto the Open’s C. W. Badenhausen champions’ trophy four times before he sank his last putt.

Babe was reanointed by his NJPGA peers as the 1960s Player of the Decade. With Open wins in 1965 (Spring Brook Country Club) and 1969 (Rockaway River Country Club) supported by second-place silver in 1963 and 1968, he seemed omnipresent. Hanging his hat at several clubs over the span of the decade, he also found himself on and off the PGA Tour, befriending Sam Snead, Tony Lema, and others with his charismatic but irreverent ways. In 1971, Lichardus became the first player to win four New Jersey Opens, taking his time in the process. He won his last Open at Montclair Golf Club, almost twenty years after his initial 1952 Open victory.

The Opens of the 1980s were dominated by David Glenz, who won the Open four times (1984, ’86, ’88, and ’90) in just seven years. His play was special enough here and in other professional state events that he was voted the NJPGA’s Player of the Decade. By the mid-1980s, Glenz was head professional at Morris County Golf Club and was also developing a reputation as one of America’s finest instructors. In the early 1990s, Glenz opened up his own instruction school in Crystal Springs and, in 1998, was recognized by the PGA of America as National PGA Teacher of the Year. Glenz has continued to grow, becoming a principal behind the decade-long creation of impressive Black Oak Golf Club over the early 2000s.

For contributions to New Jersey golf that went beyond his exceptional golf, Glenz was inducted into the NJSGA Hall of Fame in 2022. In a telling moment, he shared the HoF dais with his protégé, Karen Noble, who credits Glenz for guiding her development as a top amateur, touring professional and now, instructor. Nearly as impressive as Glenz’s 1980s Open dominance was Ed Whitman and his three ’90s Open wins (1991 at Rock Spring Club, ’95 at North Jersey Country Club, and ’96 at Essex Fells Country Club). The head professional at Knickerbocker Country Club for more than three decades (and now its pro emeritus), Whitman’s triumph at Rock Spring was truly that, posting an Open 72-hole record 17-under-par 267. Whitman carried his success into the new millennium, with his fourth Open at Crestmont Country Club in 2004 at age fifty-two. Whitman has been named NJPGA Player of the Year five times, won over 225 professional tournaments, and captured twenty Garden State major titles. Recognized as both a great golfer and a consummate golf professional, Whitman was inducted into the NJSGA Hall of Fame in 2022.

His colleagues have taken note, voting him into the NJPGA Hall of Fame in 1996. Word is, they might have also passed the hat several times in a bid to get Whitman to retire from competition. That’s quite likely another experience that all three of these fourtime champions have in common.

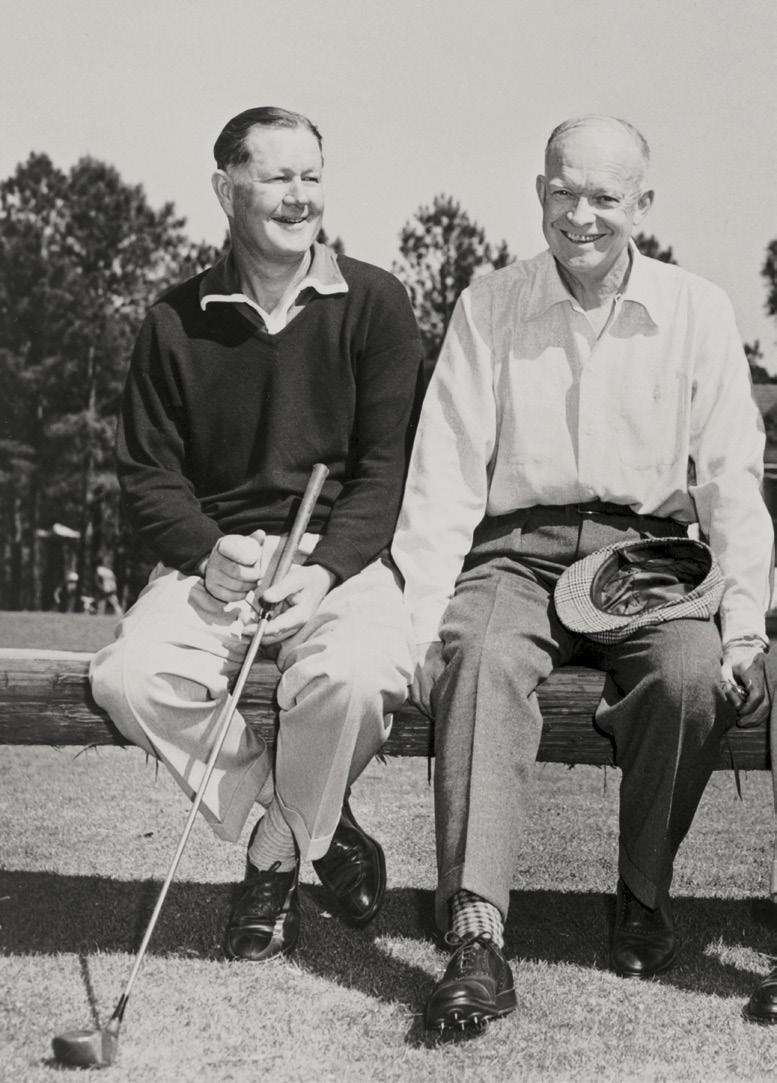

OPPOSITE: The New Jersey State Open C. W. Badenhausen trophy. ABOVE: New Jersey State Open winners: (top) Babe Lichardus, (1952, ’65, ’69 and ’71); (left) David Glenz (1984, ’86, ’88, and ’90); (right) Ed Whitman (1991, ’95, ’96, and 2004)

SOMERSET HILLS COUNTRY CLUB

A Special Place

SOMERSET HILLS COUNTRY CLUB, in Bernardsville, was once described by Frank Hannigan, a longtime member and former USGA executive director, simply as “a special place.”

Hannigan was a golf administrator, sportswriter, and television commentator whose long involvement in golf took him to virtually every sanctuary of the game. In that context, he used his three-word description in the strictest, most exacting sense. Somerset Hills’s members, struck by the understated relevance of Hannigan’s phrase, embraced it as the title of their 1990 club history book.

It fits perfectly.

Do It Right, With Grace and Respect

Somerset Hills dates its origins to 1896, when a group of local landowners with close ties to New York City formed the Ravine Lake and Game Association. The club itself was started in 1899. Its early nine-hole course was considered good for the day, but by 1916, the club moved to the 190-acre Frederic Olcott estate in the hills just outside Bernardsville, which included a private horse racetrack and remains its home today.

The clubhouses at Shinnecock Hills, Cypress Point, and Somerset Hills are in the same genre in that each reflects a perspective that seemed to be important to their respective founders: If you decide to do something, do it right, with grace and respect. Somerset Hills’s clubhouse, now over one hundred years old, exemplifies that idea. It is a cozy, comfortable place to gather after a round of golf or a tennis match on its grass courts.

As grand as some of the other A-list clubs in New Jersey are, Somerset Hills revels in a lack of glitter. No pretense and a studied casualness make the club a comfortable, always-friendly place to visit.

This is not what you’d necessarily expect when you learn about the membership. Gaze at the numerous club champion plaques and you’ll see last names of the hardy souls that first shaded North American soil centuries ago, led some of the most important companies in history, served our country at the highest levels in Washington or in the military, governed our state or—as previously noted—led the USGA.

OPPOSITE: Somerset Hills Country Club’s 11th and 12th greens ABOVE: The 16th hole at Somerset Hills in September 1927