ressurection

Dear Davidson,

It has been too damn long.

Hello, and thank you for picking up this sort of newspaper/sort of magazine/sort of art piece. We haven’t seen a printed Libertas since spring of 2020 when we all know what went down. But we are back!

It’s been a wild four months. Elsah James took over as Editor-in-Chief at the beginning of the 2022-3 Fall Semester wondering how she was going to put together a brand new staff of fiction and poetry editors, layout designers, and media team. One day, at a water fountain on thirdfloor Chambers, she asked Max Shackelford to join her as Co-Editor-In-Chief. Then, they got to work. The rest of the story is a rush of boring meetings and details and meetings and messages and meetings.

One of our first tasks after recruiting staff was settling on a theme for our first issue back. We wanted to be as eye-catching as the many editions of Libertas plastered to the walls of our Union office, as edgy as a sharp cliff at the top of some Appalachian Mountain, and as poetic as the writing Davidson students have to offer. We came up with ‘Resurrection.’ We don’t know that the theme met our ridiculous standards, but we think it is fitting.

We all deserve a second chance, always. And that’s what this semester has been for Libertas. A second chance at art, at beauty, at life. Resurrection captures the movement of this magazine from vibrancy to absence to rebirth, which we know does not guarantee a return to what was before. But if we can render this incipient magazine, which lies under the name and in the shadow of a past giant, into some form capturing the charm, the vision, the madness, the hope, the depth, the imagination, the wit, and all the rest, then we will cherish the fruits of our labor.

For the first time in a while but certainly not the last, thank you for reading,

Cover

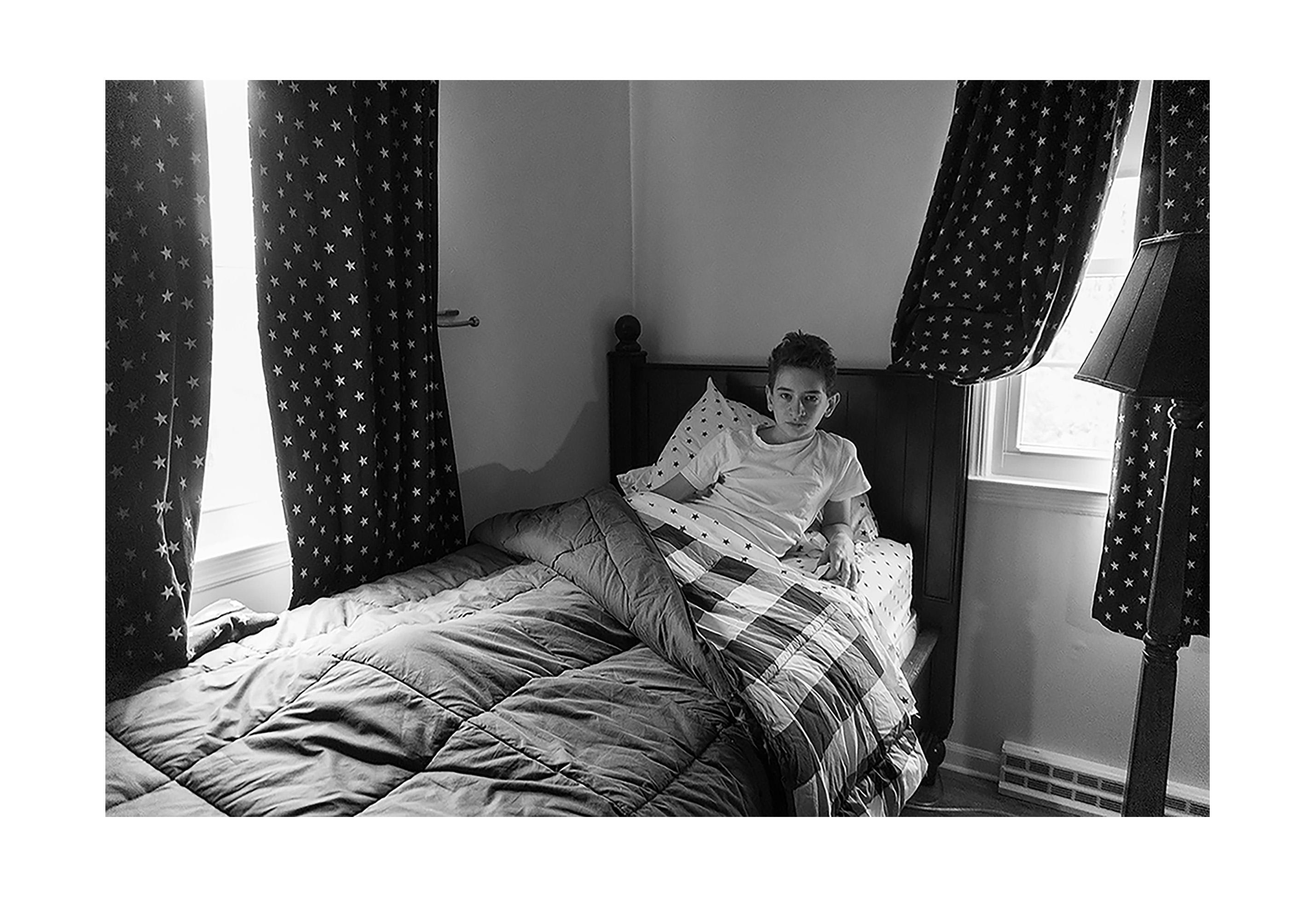

Resurrection Photography Untitled Nekyia Art Mermaid Cliff Knot What Wee’d Expect Upon Returning Sugar or Spice It’s Nice to Smell Nice Left I Must Live with You Between Grave and Sky

A Supermarket in California with Allen Ginsberg Photography

Ainsley Richardson

Mahrle Siddall Ashley Allushuski

Caroline Ewing Andrew Tinaz

Ashley Allushuski

Selin Deniz Akdogan Andre Phillips

Erin Price Quinn Benson Frank Edong’a

Elsah James Saskia Sheinkman

Mahrle Siddall

Mahrle Siddall

Whenever I look up at a brilliant green canopy, I imagine myself as a child. Climbing whatever trees had branches close to the ground so my small body could take the initial step. The bark would scrape my limbs as I surpassed the entangled branches. But I paid no mind, for my mother would cover my wounds with bandages. The band aids that covered my legs served as badges of honor for my adventure. When I reached the top, I would look at the untouched land that surrounded me. Watching as the golden grass swayed in the wind and the glow of the setting sun illuminated the forest. I would sit up there for hours until the sun was swallowed by the horizon, and the indigo haze of dusk would remind me to venture back home. At some point I became too much for the brittle branches of the red pine and they would snap under my feet. Unfit for an adolescent. The forest was no longer my domain and suddenly being lady-like was more important than being a child. I forgave the trees for not supporting my weight and exchanged them for the stability of the ground. Occasionally I would gaze at the winding limbs and think how comfortable it would be to fit into a nook created by branches. I would make plans to come back late at night when I wouldn’t have to worry about the presence of others, but it seemed that I was never alone. Much unlike home. It wasn’t until I took a walk alone through the forest of my childhood that I saw a magnificent oak among the swarm of the red pine. Its thick branches were surely enough to support my weight. I remembered seeing the oak as a child and being disappointed that I couldn’t reach the tall branches. I looked up to the canopy and saw golden light peeking through the green and decided to climb. I climbed and climbed until my limbs grew tired. Out of breath, I took in what was around me. Even though the horizon was sterile with sleek buildings and a perfect grid of streets, the forest remained. The asphalt that covered the swaying grass created a line between the natural world from the one we created. Even though the changes in landscape shocked me, my eyes were drawn to a sapling sprouting not far from the asphalt. Its tiny leaves were reaching toward the sun. I knew that in time, it would grow to overtake its surroundings. Its roots would soon become stronger than the man-made barrier, causing it to raise and crack.

I lay dormant, plastered against the walls of a sewer. My chest settled with pressure as a blunt soreness parades about my side. Bones pressed against the concrete whose stench, strikingly rotten, fills my sinuses. This

amongst the lives of those fruitful. Condemned to remain enveloped by darkness, for a step too close to a radiant lamppost, a gaze upwards at the twinkle of the stars will set my eyes ablaze. Light hurts me. Thus, for the last

An Opportunity to be together. The clouds obscure the moon’s view as the lights, beaming from the street, have gone out. It’s perfect. I squeeze through the sewer’s opening, abandoning my home which sits just before your front lawn. I race across misted grass whose droplets would shimmer on so many other nights. My footsteps, silent upon pavement, roll up those steps. My hand thrusts through the front door’s keyhole as its brass scrapes upon my skin. My pain is profuse, yet I leave no mark. I have neither blood nor skin to drip. I press my body completely through for I am driven to you, my children. I stagger upwards and stumble into the hallway, marred to look for… well…myself. Photos encased in darkly rimmed frames. Weddings, Birthdays, Recitals. Something … some marks I made. Yet I am absent. Spilling drunkenly across the living room, I see no signs. None of me. Please. Lord Please! Have they forgotten me? Have they left me beneath that hallowed ground?

No semblance of me. I … I do not exist. My eyes do not even gaze back at me in mirrors, for even they have betrayed me. I remember their rooms. They are upstairs. I dash as the lights of passing cars dagger through windows, slicing across my stomach. My guts exposed, yet I keep going. To the stairs I climb. A gentle ceiling light blocks the top and I hug the wall as I approach. It bars me from you. I will myself through. My back burns as the light blazes across it. “I am so close”, I murmur to myself. Air vents, dusty, dank, and cobweb-covered, lash out at my face. I keep crawling until … Yes! There they are! Michael! Rosa! My sweet children. I reach my hand out to cup their faces and to let them know I’m here. This is futile. I lay kisses upon their foreheads that they cannot feel.

“Michael. Why do you dream with spite? Do you resent me? Why do you cry so forcefully?”

“Rosa. Why do you frown? Do you not think of me fondly? Do you forget me?” “Why aren’t there pictures?

MY CHILDREN WHERE ARE THE PICTURES? Where are the drawings of me? The letters to me? I can see you!

I can hear you! Please! Please don’t forget me!”

I stumble about frantically searching. Perhaps in their dreams there is me but … nothing more? I need something to place my faith into. Something physical. I need … My eyes land upon it. A photo of me reclined watching TV. This … This one memory. This … would rattle around their minds for the rest of their lives … I … I don’t want that. I want them to flourish. To look upon life contrastingly. I taught them that … I taught them well, right? My burned flesh stinks only to me. My skin sheds, pattering upon the wooden floor. I heard it. I hear my breathing, my struggle to get to you! You can’t appreciate it. You won’t know that my tears, though silent, they only shed for you. So I can say which I may only perceive, “I’m sorry … I’m sorry I was a bad father and cannot give you more time.” The Sun’s rising fire drags me back towards the sewers. Down to the world untouched, blind to even me. Know, my children, that I etch my struggle into my new home’s walls so it is to be near you. So that if you ever wander, know I will be with you. Know that I, at every moment, every waking second, will attempt to imprint myself upon your skulls. I long to be restless, not dormant. My children, I need you … for your memory of me … I suppose it renews me.

The boy led his grandpa deep into the woods, towards the sound of rushing water, away from the sounds of rushing people. When they first began their hike, they heard the bustling of cars louder than the rustling of leaves, the honking of horns louder than the honking of geese, the whirring of machines louder than the whirring of insect wings. Now all they could hear was flowing water.

Each side of the trail was heavily vegetated by knotweeds, which — with their thick, bamboo-like stalks, wide leaves, and roots so robust that they seemed like subterranean trunks — were considered invasive to the area. Eventually the boy and his grandpa arrived at a spot where a rock stretched out into the river. Knotweed still grew to their right, but to their left was the unhindered sight of the rock and the river.

“Here it is! My favorite spot in the woods.” exclaimed the boy, whose name was Delo.

“It is nice here,” remarked his grandpa, “just a bit sad.”

“Sad? Huh.”

Delo sat down on the rock,

placing his hands behind him as support. A small smile stretched across his face as he gazed out at the river. The smile faded when he glanced to his right and saw the knotweeds.

All his life, Delo had lived in Keyston, a small, historic town that had been built along the Lenni river. It was a quiet town. In the past, each home had about an acre of land, and the forests were still mostly intact. Until recently, the town had not changed much. But that was before the invasion.

In recent years, a flood of city people had begun to erode Keyston’s land and its tranquility. Intensive construction operations destroyed the forests and disrupted the silence. New homogenous houses and hypermarkets blemished the town’s once unique aura. Local businesses were overtaken by the self-proclaimed economically educated city-comers. The local government had become dominated by ex-urban bureaucrats, who used their power to avoid assimilation and change Keyston to their ideal, suburban paradise.

The knotweeds reminded Delo

of this phenomenon, this sort of countryside gentrification. When the city people came, they constructed houses so close together that they resembled the dense configuration of knotweed colonies When the city people came, they built standardized structures that cultivated a monoculture akin to the acres of knotweeds in the riparian forest. When the city people came, they embodied an air of untrustworthiness that was like the leaves of the knotweed which covered any visibility of the forest beyond the trail.

Delo shuddered, letting his head fall limply. “I hate the knotweed,” he muttered to himself.

“So you don’t know the knotweeds yet,” murmured his grandpa.

“Huh? Know the knotweeds?” scoffed Delo.

Delo, who had passionately researched Japanese Knotweed for school, began listing out superficial facts about how knotweed is an “invasive species” and how it has thick roots called rhizomes and how those rhizomes… His grandpa did not care to listen, having

Andre Phillips

Andre Phillips

already heard Delo rant about the knotweed on the way to the river. Instead, the grandpa looked towards the mass of vegetation to his right: a green, semipermeable wall of leafy stems reaching 6ft high. He scrutinized these stems for a few minutes: seeming to gather information by listening to the bending stalks and rustling leaves, peering deeply into the green amalgamation as if it had something to say to him.

The knotweeds told the grandpa what search engines couldn’t tell Delo: “We are the ones who grow on the sides of volcanic mountains,” the knotweeds whispered as they swayed in the wind. “The ones who bring life to the flakey ash. The ones who live unobstructed by obsidian. When the wind blows, soot covers our leaves, but that does not stop us from seeing the light. When the earth shifts, our stems bear the barrage of rocks to follow, and our roots remain steadfast. We are not from here, but we like it here, because life is easier here.”

After listening to the knotweeds’ tale, the grandpa recounted, “The knotweeds need this sort of life. Things are less busy for them, things are easier.”

“Well they shouldn’t be here. They just take everything over. And it’s not fair for the other plants,” grumpily replied Delo.

“What is so bad about them having an easier life? When life is hard for us, we move. We go to some place where we think we’ll be happier. That’s why me and you are here right now.” The grandpa leaned back and smiled as Delo had earlier, reminiscing about when he and his family first moved from the city to Keyston. He recalled how he longed for somewhere more peaceful or friendly or beautiful, somewhere with a lighter burden. He recalled how he found what he was looking for in Keyston.

Keyston was a place where the world smiled back. The corners of the forest arched upward like dimples, the ripples of the river seemed to grin, the people emanated elation. Even with the invasion of city people, the grandpa relished in Keyston’s blissful charm. Everyone living in Keyston wanted to be there; that’s what made it so special to the grandpa.

“I moved here 34 years ago and look at how well our family has done!” the grandpa chuckled, “Why can’t plants

do the same as us?”

make everyone else move. The knot weeds make all the other plants move and the land change,” Delo argued.

to be here more than the other plants, so they grow back quicker,” his grandpa insisted.

unhappy environment for themselves by doing that?”

slouched forward, resting his head on his arms to gaze at the river. He stared at one particular section where an anomalous ripple pattern kept forming over and over again in the same spot. The ripple was occasionally interrupted by leaves or branches floating down the river. But once those interruptions had drifted away, the ripple returned to its original configuration.

much longer,” murmured the grandpa.

some space for others while they’re here?”

grandpa, his stature beginning to stoop.

knotweeds again. Despite their vivacious green glow, the knotweed stems seemed to droop. One knotweed drooped as if hanging its head in shame. Another drooped as if it was looking for some thing lost. Yet another drooped as if it was lamenting a loss. The grandpa got up and walked toward the cluster of cowardly looking knotweeds. He looked towards the ground where there was a recently snapped stem. Sorrowfully, he knelt down to examine the stalk more closely. It was still perfectly green, but the inside was hollow.

mured, “You just have to keep coming back.”

One time, I met Ms. NC at the fairground That night, I dreamt she placed a bomb in my stomach She said she’d watch, she’d know if I talked and so, I began to understand my surveillant subconscious

Close up, I lashed at masqued girls’ clumped lashes Closed up, I salivated at their sweet potion Quaking cake face, I asked what is that Oh me? VS Warm Sugar Cookie. Come, walk into mist no. 5

And then, we all Judy Bloomed... All over the hallway. Heh, ah excuse me, we were fermenting there.

It felt like poolside mom’s-night sangria It smelt like when you stand up way too fast My brain became all hypertonic come now, socratic-stall seminar if you please, walk me to class

A note, once wrote me “you don’t know your power” OH MY pride at our group show-and-tell catty calls We had all thought it’s nice to be crushed so rushed, too distilled, my happiness caramelized into caution

My skin ran dry from powders

Cinnamon challennnnge! hgueeeh! I gagged on spoons full of compromises

Pick up, benefit of the doubt boomranged I felt lucky Luck had called me a feminist Now made brittle, I got a clean break, Escapes! Over spritz’ dew I forget it just feels nice to smell nice

And then, walks in my marsupial roommate And now, we incubate in our lavender womb, we build out sense while with-in-scents we walk in her spritzes of Happy, Clinique’s signature fragrance.

A crush once wrote to me that “you don’t know your power.” Hah, and I’m starting to think that is not true

To witness the reaction to your death Is to know the legacy you had It's to grapple with what should be intangible

That either you were lost in emotional turbulence Or you were sought like a destination

That either you were at buried underneath the flower: Where the wherewithal of your colleagues bars them from entering

Or you were the dandelion They always searched for

Where death isn't the end of your life Rather it's the beginning of your family's new stories

Yet maybe reincarnation is not the act of seeing your own self Or reforming in a different being

Maybe we are all reincarnated, Just because we left an impact.

- 2nd Libs North Corridor, Davidson, NC. October 24th, 2022

Winds blow and erase your face from the sand; I draw. Again. And again. And again. The Shooting Star delays, I wait in the cold gloom for that epiphany And when I see, I gasp and hope my heart steers on; I cherish the sobs from my eyes— broken reflections of you fetched from dark-bottom bowls; I must grieve, I know, For in that is a constant living dying you.

A child, you showed me the rising moon, full, glittering life in the dry of the night But there was no moon some days “It is under,” You said, “It will rise soon.” I held my patience. And so there was moon some days— Half, crooked, full And there was your finger, guiding my eye.

You did not have to go under to emerge, Like seeds shooting only from buried depths; I feel the light of your extinguished flame more now— You are no more, you are alive. And pain, Like sight, I offer outward and within, Pain, a birthright of our mutual contract For which the world prescribes I must bury you again; Pain, I have longed for you.

I must believe in the resurrection One which I wait all day long, all night long; Such things as communion of spirits Beyond this corporeal essence But until then, my Janus. Until then I must live with you between grave and sky.

Grocery List:

● 3 Avocados

● Cherry Tomatoes.

The thoughts I have of you tonight, as I hurry from my car towards the Whole Foods entrance, hot pink flip flops slapping the cracked concrete. The full moon is tucked behind street lamps, and moths swarm the bulbs in a starving frenzy. I squint up at the moon; the moon squints back, silently judging. I left the honey glaze on the stove for my pork chop recipe. It’s just missing

● 2 cloves of garlic.

If I don’t hurry, the glaze will burn and the whole dinner party will be ruined. I walk under the trees with a headache as regret settles into my joints. I should have never offered to cook. They’ll be at the house soon, and all I have is a glaze. I walk into the neon fruit supermarket, dreaming of my enumerations. I pull up this very list, dragging it from the depths of my notes app where it cowers behind a shattered iPhone screen. I need a

● Side salad

● Dessert?

● Pork chops.

Worst of all, I have no pork chops to go in my honey glaze pork chops. The Whole Foods is bright and sterile. In my hungry fatigue, the noise of the fans muddles with the voices of shoppers. Fluorescent lights and pyramids of fruit consume me.

I grab a cart and begin to weave past whole families shopping at night.

● Peaches and penumbras! I pass aisles of husbands and wives hunting for

● Non-gmo bananas.

I make it to the avocados in record time. The waxy peels glisten green. I wrestle with the plastic bag, dropping in three avocados the size of my hand, and continue down my list. An audience gathers to watch a baby tantrum in the tomatoes, arms flailing dangerously close to the ripe fruit. The rows of red reflect the fluorescent lights like sunburnt cheeks. Picturing the baby knocking down the pyramid, red guts splattered across the tiled floor, I steer my cart to avoid the tantrum. The salad will be fine without cherry tomatoes.

● Cherry tomatoes

● Soy sauce

● Spinach

The spinach is sweating under the mister, timer clicking at me. I grab the nearest bundle but seeing the way the greens droop, I put it back. There is plenty of spinach, I can pick the very best. Produce abounds in a land of plenty. Plenty of drought. Plenty of chemicals piped into food. Plenty of freezer meals and freezer burn. I need to go to the frozen section next. I’m frozen in time while everyone around me grows up and creates a family. And all I have is my dinner half missing and half burning. And they’re expecting a meal when they arrive. I need to get out of the produce section.

● 1 hallucination

It’s not until I make it to the back of the store that I see you, Allen Ginsberg, childless, lonely old grubber, poking among the meats in the refrigerator and eyeing the grocery boys. Bespectacled and murmuring. Allen’s beard points a million directions, his tie askew. He has a book

tucked under his arm, just how I imagined him in high school English class, straight out of the Beat generation. I can’t remember when he died, but I remember learning that he was dead. He pauses right where I need to get the ● Pork chops.

I study you as I approach the pork section. Everyone else walks past, shrugging off the unusual Santa Monica characters, but I recognize you. Gingerly, you reach in and grab a styrofoam parcel. The saran wrap seems to laugh, reflecting in the glass door. Allen Ginsberg grabs pork chops. The last package of pork chops.

“Excuse me,” I say, “Did you just grab the last pork chops?”

You turn, looking past me instead of at me. “You see him, don’t you?” He points to the space behind me. “Walt Whitman is in front of the chicken.”

I turn, there’s no one there. I’m alone in the aisle. I swallow both pride and panic. I need those pork chops.

“I’m really sorry to bother you, but I am in the middle of cooking honey garlic pork chops and I made it all the way through the glaze before realizing I didn’t have pork chops and I left the glaze on the stove and I have guests coming over in like thirty minutes and those are the last pork chops in the store.” I take a breath. “Is there any chance I could have the ones you just grabbed?”

“I picked them up first,” the man says.

“I really need them.”

His eyes dart between the empty space and me. He opens his mouth, then closes it again. When he speaks, I am unsure if it’s meant for me.

“Answer me this,” Allen says. “Okay.”

“Who killed the pork chops?”

I hesitate. Calculating. “The farmer, I guess.”

You frown. Turning to the empty space next to me, “And who do you think, Walt?” Allen asks the space where I suppose Walt Whitman is standing, though I see only my own reflection in the refrigerator glass. After a moment of silence, Ginsberg nods, as if happy with the answer of the dead poet’s ghost. ● “America.”

Allen walks toward me. I reach out to accept the pork chops, but he doesn’t give them to me. Instead, he continues down the aisle, beckoning for me to follow. Out of curiosity and desperation, I do. Bewildered, I ask one more time, “Can I please have the pork chops?”

“Whitman and I are having them.” I want to scream that there is no one else in the aisle, that I have a pot sitting on the stove that could burn any second. We wander in and out of the brilliant stacks of cans. I’m right on his heels. He never once passes by the cashier. I watch him watch the space in front of him intently. He stares into the back of Walt Whitman’s head. I’m nearly running to keep up, but then Ginsberg snaps out of his stare. Instead, he shops for images, soaking in every ounce of the Whole Foods. In his solitude, he picks up various items. He reads the label on the

● Canned corn.

He’s amused by the ● Artichokes

● And the Green grapes,

plops into his mouth. I follow back around to the produce side of Whole Foods. Back into the crowd of vegans, vegetarians, and wannabe models in the seasonal vegetable aisle. Would they see him? Would they stop him from taking their dinner? Should I reach for someone to help me? I follow Allen Ginsberg as he follows Walt Whitman around the Whole Foods. I’m absurd. I’m helpless. My dinner menu goes down the drain with my sanity. My house is probably burning to the ground at this moment. I’m going to starve and I’m going to have nowhere to sleep and everyone is going to hate me for not having anything for them to eat at dinner. I’m craving ● Oreos.

The one food that solves everything. I risk looking away from Allen for a moment as I grab the impulse buy off the shelf. I turn back just as he ducks away from the food.

Allen completes his odyssey in the supermarket. He leaves Circe with no pork to eat on her island. He pays for nothing, walking straight to the sliding doors. I’m following. I will steal these oreos. I’ll do anything to catch up to this man. I debate wrestling the pork chops out of his hands. He turns. It’s like he heard my thoughts. I stop. He points at me with a nail chewed down to the quick. I open my mouth, but he cuts me off.

“Are you my angel?”

Elsah James Max Shackelford

Emma Anglin Caroline Redesky

Ashley Allushki

Katie Forrester

Bianca Hassan Andre Phillips Andrew Tinaz Flora Konz

Phoebe Anderson

Eliana Burgin Erin Price

Savvanah Vonesh

Audrey Bohlin Avani Damidi

Emma Huff

Gretchen Upton Gabriel Wilson

Emma Anglin

Audrey Bohlin

Mahrle Siddall