Dealing with Deconversion: THE MALAISE OF FRAGILIZED FAITH

FRUITFUL FAITH IN THE AGE OF DECONVERSION

Ed Hindson THE CHRISTIAN AND THE CRITICAL SPIRIT

Andrew Walker

AN INTERVIEW WITH IVAN MESA

Ivan Mesa and Jack Carson IS APOLOGETICS PART OF THE PROBLEM?

Mark Allen

Fall 2022

Jack Carson, Executive Editor 2022Mark D. Allen, Executive Editor 2018-21

Benjamin Forrest, Managing Editor

Seth Pryor, Assistant to the Managing Editor

Zane Richer, Assistant to the Managing Editor

Joshua Rice, Creative Director Heidi Schieber, Marketing Director

Seth Bingham, Marketing Manager

Victoria Cline, Project Coordinator

Deanna Sattler, Designer

Dave Parker, Senior Writer

FACEBOOK/LibertyUACE | @LibertyUACE | envelope ACE@liberty.edu | location-arrow Liberty.edu/ACE Dealing with Deconversion: The Malaise of Fragilized Faith 7, no. 1 (Fall 2022): A publication of Liberty University Center for Apologetics & Cultural Engagement

9 THE PRESSURES OF DECONSTRUCTION: REFLECTIONS OF A LIBERTY ALUM

Jack Carson

38 DECONVERSION, THE PROBLEM OF SUFFERING, AND THE GOD WHO DEFEATS EVIL Ronnie Campbell

50 DECONVERSION: ARE WE BLAMING THE VICTIM?

Linda Mintle

64 OUR MARRIAGE OF PHILOSOPHY AND EDUCATION

Mike Jones

Laura Jones

FAITH AND THE ACADEMY: ENGAGING THE CULTURE WITH GRACE AND TRUTH i

8 The Passing of a Baton

Mark D. Allen, Professor of Biblical and Theological Studies, John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

9 The Pressures of Deconstruction: Reflections of a Liberty Alum

Jack Carson, Executive Director of the Center for Apologetics & Cultural Engagement, John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

12 Is Apologetics Part of the Problem?

Mark D. Allen, Professor of Biblical Studies, John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

18 The Letter to the Hebrews and Deconversion: The Struggle for Spiritual Maturity or Security

Leo Percer, Professor of New Testament Studies, John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

22 A Refuge for the Deconverted

A. Chadwick Thornhill, Department Chair of Biblical and Theological Studies, John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

26 Conceptualizing the Psychological Dimensions of Deconversion

Keith Lahikainen, Associate Professor of Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences, Liberty University

30 An Interview with Ivan Mesa

Ivan Mesa, Editorial Director for The Gospel Coalition, Editor of Before You Lose Your Faith: Deconstructing Doubt in the Church

Jack Carson, Executive Director of the Center for Apologetics & Cultural Engagement, John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

34 The Christian and the Critical Spirit

Andrew Walker, Associate Professor of Christian Ethics and Apologetics, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary

38 Deconversion, the Problem of Suffering, and the God Who Defeats Evil Ronnie Campbell, Associate Professor of Theology, John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

41

“Love God, Love Others”: Ordering the Operations of Affection

Benjamin K. Forrest, Professor of Christian Education and Associate Dean, College of Arts & Sciences, Liberty University

Jason Glen, Instructor of Ethics and Interdisciplinary Studies, College of Arts & Sciences, Liberty University

4

ii

Contents

47 Fruitful Faith in the Age of Deconversion

Ed Hindson, Dean Emeritus and Distinguished Professor of Religion, John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

50 Deconversion: Are We Blaming the Victim?

Linda Mintle, Chair of Behavioral Health at the College of Osteopathic Medicine, Liberty University

55 Faculty Instrumentality for Defending the Faith: Encouragement against the Philosophical and Pragmatic Foundations for “Deconversion”

Bernard J. Mauser, Adjunct Faculty, John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

INTERDISCIPLINARY ESSAYS

60 The Many Forms of Stewardship (and How to Live Them)

Timothy Yonts, Instructor of Ethics, College of Arts & Sciences, Liberty University

Stacie Rhodes, Associate Professor, School of Business, Liberty University

64 Our Marriage of Philosophy and Education

Mike Jones, Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies, College of Arts & Sciences, Liberty University

Laura Jones, Adjunct Professor of Education, School of Education, Liberty University

5

iii

FAITH AND THE ACADEMY: ENGAGING THE CULTURE WITH GRACE AND TRUTH

Training Champions for Christ since 1971

Editorial Note Mark D. Allen Professor of Biblical and Theological Studies, Executive Editor, Faith and the Academy, 2018-2021

Editorial Note Mark D. Allen Professor of Biblical and Theological Studies, Executive Editor, Faith and the Academy, 2018-2021

John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

The Passing of a Baton

In high school, I ran the first leg on our 4x100 relay team. Nothing felt better for me than to take the lead, pass the baton off smoothly, and then watch my teammates increase our lead. I learned the importance of a smooth hand off and the joy of watching my teammates succeed.

This summer, I passed the baton of leadership of the Center of Apologetics & Cultural Engagement to Jack Carson. Jack is an able leader who will take the center further than it has ever gone.

As the center’s coordinator, Jack has been the energy behind the center’s structural development and unique vision. For years, Jack has served as the associate editor of Faith and the Academy, and now he takes up the mantle of executive editor of the journal.

Jack is eminently qualified to lead the next leg of ACE and F&A. He is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Aberdeen in public theology, experienced administrator, and co-author of a book designed to persuade those considering deconversion to remain true to Jesus Christ and His Church. Brazos Press will release the book in the summer of 2023.

The work we have done at ACE and through F&A has been spiritually and professionally satisfying for me. I especially enjoyed mentoring students toward a more intellectually robust, theologically rich, and genuinely kind approach to cultural engagement. Beginning this year, I will teach more Ph.D. and graduate courses in public theology within the School of Divinity and will turn my focus toward writing and research.

Jack, the baton is in your hand. Run the race well, my friend.

Jack Carson Executive Director

Center for Apologetics & Cultural

Engagement

John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

THE PRESSURES OF DECONSTRUCTION: REFLECTIONS OF A LIBERTY ALUM

I started my undergraduate program at Liberty University in 2013. Since then, I have had a number of my friends — young people who attended Liberty for four years — "deconstruct” their faith and ultimately walk away from Christianity. If you have been teaching here for any length of time and have been able to stay in contact with your former students, I am sure you know some names that match the stories below.

At first, this trend toward deconstruction was surprising. My youth group years set me up to believe that Christianity was obviously true — doubt was silly, stupid, or sinful. When I came to Liberty, I stepped into a carefully cultivated community that reinforced belief and exterminated doubt. This was very helpful for me at the time. But it made faith seem easy because everyone around me believed.

Faith, it turns out, isn’t always as easy as I thought. I’d like to introduce you to Kayla, Ashley, and Bill.

Kayla and I were in the same friend group throughout our undergraduate years. We had study sessions together and regularly attended the same dorm-sponsored board game nights. Kayla was an exemplary Christian young woman. She was a resident shepherd who cared deeply about the girls on her hall, and she went out of her way to disciple them and care for them when they were homesick or depressed. She was selfless, kind, and funny. She was regularly mentored and discipled by her own LU Shepherd, and she shared with her friends how the Lord was shaping her and challenging her.

Kayla now identifies as a lesbian and has renounced her faith. She looks back on her time here as repressive and spiritually manipulative. In the traditional Southern Baptist environment both Kayla and I grew up in, people bluntly explained that it is impossible to be Christian and LGBTQ+.

As Kayla tells her story now, she was experiencing same-sex attraction the entire time that she was at Liberty, and she kept praying that God would deliver her from it. She has shown me the journal pages where she prayed week after week to be saved from same-sex attraction. And it never happened for her. She remained attracted to girls and eventually came to accept that since she was attracted to females, she can’t be a Christian anyways. So she gave up and publicly “deconverted.” Christianity just didn’t “fit” Kayla anymore.

Ashley was — like Kayla — a seemingly devoted Christian. She grew up attending a private Christian school, and her entire childhood was steeped in conservative Christianity. Her parents kept her from dating, bought her a purity ring, and sent her off to Liberty University to — presumably — find a nice Christian husband. They didn’t quite get the outcome they hoped for.

As Ashley began to reflect on her childhood, one word began to dominate her memory of it — abusive. Not abusive in a physical or sexual sense, but abusive in a more ineffable way. As she remembers it now, her beliefs had been forced on her, and her freedom of thought had been restricted. At first, she thought that her parents were an anomaly, and she explored other forms of Christianity. She began to find each successive Christian author to be more frustrating for her faith. Each of them seemed so confident in their framing of Christianity, and each of them wanted her to believe exactly what they believed. This seemed quite similar to her parents. Ashley wanted to be a Christian, but the whole structure of Christianity now seemed tainted to her. The whole thing just seemed to be about power. This was exacerbated as she began to see spiritual leaders — the same ones who had publicly taught her to “keep herself pure” — become exposed as incredibly immoral

Pre-Editorial

individuals in their private lives. I tried to tell Ashley that Christianity is broader and richer than she could see at the time. I tried to explain that Christianity helped give the modern world its idea of freedom and provided it with the metaphysical resources to believe in human rights. I tried to show Ashley that the failures of particular Christian leaders don’t necessarily demonstrate the failure of Christianity itself. But for Ashley, Christianity just didn’t seem good anymore.

Bill, like the others, came from a Christian home. Bill, though, had been voicing doubts for a long time before he came to college. It seemed to him that no one had satisfying answers. He was curious about how Christianity fit with modern science. He wanted to know how Christianity explained the data that led so many people to believe in evolution. To answer these questions, he pursued a minor in Christian Apologetics once he got to college. He wanted to solve his doubts, and he was willing to put in the work to make that happen.

And Bill’s search seemed to work. Or, at least, it did at first. He would find a satisfying answer to some issue — say, the criticism of the New Testament account’s reliability — and then he would be certain of his Christian faith for a while. Eventually, however, a new argument challenging Christianity would present itself to Bill in some YouTube video or Reddit thread. This new argument would throw him into another season of doubt, another season of searching. And the cycle would continue. Eventually, it seemed that Bill’s motivation to remain a Christian just began to putter out. It was too much work — there were too many arguments against Christianity. At least for now, Bill has given up on trying to banish those doubts that have plagued him for so long. He has “deconverted” and no longer believes that Christianity is true.

As I have watched these friends and others struggle with their faith, I have become convinced that I was misled. My experience has shown me that serious people can look into Christianity and even grow up in Christian spaces, but end up not believing for reasons that we both understand and should be sympathetic to. Simply piling on more data or providing more prayer sessions doesn’t seem to be the whole solution — Kayla, Ashley, and Bill had plenty of both.

I want to propose a different route for us, here, at Liberty University. I didn’t choose Kayla, Ashley, and

Bill at random — there were many other stories that could be told. These three represent “archetypes” of doubt. Kayla grew to doubt the beauty of Christianity. For her, it seemed to impoverish life of certain joys, namely sexuality. For Ashley, she came to doubt the goodness of Christianity. Christianity seemed to represent something evil and nefarious to her. For Bill, he came to doubt the truth of Christianity. It just didn’t seem to align with the story he was hearing from people outside Christianity.

We won’t be able to stop all our students from “deconverting.” No matter how much time we put into that effort and how well we design our system, some students will walk away.

But if we take their doubts seriously while they are here — if we treat them with dignity even when they doubt the beauty, goodness, or truth of Christianity — maybe more of them will be willing to open up while they are here. Maybe we can keep them from walking through the pressures of doubt alone after leaving Liberty. And maybe, just maybe, if they feel like the faculty of Liberty University care about them enough to listen to their doubts, they might be more inclined to come home after they find that the world outside of Christianity isn’t all it promises to be. It isn’t more beautiful, good, or true.

I doubt that the prodigal son would have run home if he didn’t believe — somewhere deep in his heart — that his father would still treat him with dignity, despite his many failures.

The articles contained in this journal represent a range of reflections on the phenomenon of deconversion, and we have done our best to allow different voices to contribute unique thoughts. They do not all take the same approach, and the editors would not agree with all the reflections contained within. We think this is healthy.

Ultimately, we hope that each article in this issue will help you reflect on ways to be a figure of love for the students who will hopefully become that prodigal.

1 To protect the privacy of my friends, I have provided pseudonyms and mildly adjusted some of the superfluous details of the stories I record here.

2 The following two stories contain material adapted from a forthcoming book: Joshua D. Chatraw and Jack Carson, Surprised by Doubt (Brazos Press: Grand Rapids, 2023).

10

NEXT GEN Apologetics Conference “Beauty, Narrative, and Spiritual Formation” with Taylor Worley and Eunice Chung. EIGHTH ANNUAL Visit LIBERTY.EDU/ACE for more details. In partnership with the Center for Apologetics & Cultural Engagement and the Center for Youth Ministries. NOV. 7-8, 2022

Mark D. Allen Professor of Biblical and Theological Studies, Executive Editor, Faith and the Academy, 2018-2021 John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

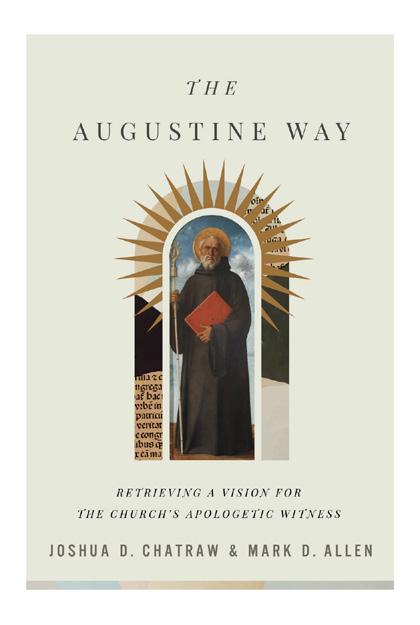

IS APOLOGETICS PART OF THE PROBLEM?

Public deconversion1 stories have become a thing over the past several years. Well-known pastors, contemporary Christian music artists, and other public Christians are leaving the faith in an “out loud” manner. Perhaps closer to home, children and grandchildren give up believing and say so. Christian day school and college graduates give “testimony” to how they came not to believe in Jesus Christ anymore. They have walked the Romans Road, only this time they traveled back down that rocky road toward unbelief. Many of these coming of age stories include gut-wrenching accounts of how, both intellectually and morally, the Christian faith seemed no longer sustainable. Christianity appeared neither true nor good any longer.

Perhaps no deconversion stories are so raw, honest, and thoughtfully articulated as those of Rhett2 and Link,3 the lifelong friends, Bible-belt, “born again” Christians, former CRU staffers at North Carolina State, and now, cohosts of the YouTube series Good Mythical Morning and the podcast Ear Biscuits. The two are very relatable, likeable, intelligent, and engaging comedians who draw listeners in through their funny and interesting takes on everyday life. Their popularity and net worth have soared. At the time I am writing this editorial, Rhett’s deconversion story has been viewed over 1 million times and Link’s account of his own journey away from the Christian faith has been watched over 700,000 times.

If we listen closely to their testimonies of deconversion, we will pick up on the startling issue that, especially for Rhett, apologists were part of the problem. He turned to Christian apologists — the names of whom we would all recognize — for help, but they proved ineffective to shore up his faith. For them, skeptical and critical arguments were more persuasive and believable and — in the end — seemed more honest. At one point, Rhett even became angry at Christian apologists whom he felt deceived him.

We could write them off as a couple of Southern boys with a shallow faith who made it big in California and

then found convenient reasons to walk away from Jesus Christ and His Church. We could claim that they did this because they wanted to be free to indulge their egos and enjoy the benefits of money and popularity. Granted our social location can shape the way we see the world and the things we value. But if we listen closely and empathetically to their stories, there’s more to it than that. Their faith started to unravel even before they left North Carolina and landed in California.

Why? Philosopher Charles Taylor acknowledges in his Templeton Prize-winning book, A Secular Age, that we live in an age in which belief has been “fragilized.”4 The cross-pressures that 21st century people feel due to the multiplicity of spiritual and livable options has overwhelmed us to the point that wherever we stand seems insubstantial and unstable. Today, technology has made us very vulnerable to challenges to our faith and opened us up to the reality of other viable options. Good and smart people are inhabiting the world in an ever increasing variety of ways. And social media makes us an audience to all of it. Now, when we believe in something, we are haunted by a sense of the contestability of our faith. (Yet, the opposite is also true: when we do not believe, we are haunted by the presence and possibilities of the transcendent. Unbelief is fragilized as well. This opens a door for apologetics.) The point is, in the 21st century, Christianity is not the natural default position that it was in AD 1500. Then, it felt almost impossible not to believe. Today, it feels almost impossible to believe. We exist in a malaise of fragilized faith. Maintaining our faith in such a skeptical world with so many life options is overwhelmingly challenging. Rhett, Link, and others began to feel the fragility of their faith even while in North Carolina and — so far — have found it impossible to remain true to what they once believed.

A question remains: why couldn’t traditional apologetics serve people like Rhett and Link? Or perhaps better, is apologetics a part of the problem in many deconversion stories?

12

Editorial

If you expect me to say in general that apologetics is not part of the problem, you’re right. For goodness sake, I co-authored a recent textbook on apologetics, and, along with Josh Chatraw, I am presently writing another book on apologetics. I am not about to deconvert from apologetics. Yet, I have to admit that a certain kind of apologetics might be part of the problem. This insufficient approach did not stop us from getting here and probably won’t get us out.

When is apologetics unhelpful for those considering deconversion? Apologetics is a part of the problem when:

1. It promises absolute certainty.

When apologists claim, “We can prove that God exists,” they have overreached and set the Christian faith up to fail. It’s not surprising that when we claim such high levels of certainty that believers jump ship into the waters of agnostic uncertainty. Further, an apologist with a lack of epistemic humility is offputting and borders on the dishonest. Of course, as missionary Lesslie Newbigin and others have argued, we can have a “proper confidence.”5 Today, a certain kind of Christian certainty, properly defined, always contains an element of volitional intentionality in the midst of other viable options and haunting doubt.

2. It thinks that it is using “universal logic.”

Often what comes across as pure rationalism is actually the quick wittedness, persuasive powers, and assertive personality of the apologist. But, in truth, there is no view from anywhere, no purely objective, rationally coercive line of reasoning that will inevitably end up at the undeniable conclusion that Christianity is true.6 You know an apologist has gone too far when he or she brashly states or, even, subtly implies, “Any intelligent person would see that Christianity is right; to think otherwise is just plain dumb.”

3. It depends too much on cognitive arguments.

When an apologetic approach focuses almost exclusively on the mind without giving adequate attention to a person’s cultural embeddness or his or her human affections, it has sacrificed a mode of reasoning that has the power to make sense to the whole person. As Blaise Pascal has said, “We know the truth not only by means of the reason but also by means of the heart,”7 and, most famously, “The heart has its reasons which reason itself does not know.”8

4. It believes it has a “silver bullet” argument

Whether it is evidence for the resurrection of Jesus Christ or 5 ways to demonstrate God exists, apologetics fails when it has a one-size-fits-all argument. Those who use these arguments most effectively consider cultural factors, are aware of the problem of doubt, and show sensitivity to the experiences and perspectives they are talking with. The best arguments are person-centered, tailored to the realities of the human sitting across from us. The knockout punch arguments may rally the already convinced or make for clickbait on social media, but used simplistically they are rarely effective in persuading a straying sheep to return to the fold.

Apologetic methodologies which were developed out of and in response to modernity truly have some very important contributions to make in late modernity. Obviously, evidential and classical apologetics, which emphasize material proof and logical analysis, have huge upsides to strengthen faith and inspire confidence in the legitimacy and cogency of belief. Just for good measure, add to the mix the incredible gains in moral arguments for Christianity developed in the last several centuries. These are significant apologetic advances. Yet we need to reimagine their usefulness and their place in the midst of the epochal change from modernity to late modernity. Apologetic methodologies9 that were developed out of enlightenment rationalistic and empiricistic epistemologies must be chastened, reshaped, and recontextualized in order to help those late moderns who are considering walking away from the faith. Many of them are deconverting in spite of what we would perceive as insurmountable evidence and irrefutable arguments.

Here’s the kicker. Many Christians who were raised on these modern apologetic methodologies — having learned them in Sunday school, youth group, and college ministry — are walking away from the faith based on what? Based on what they perceive as better evidence, logic, and morality! What?!

So, is apologetics part of the problem? Yes and no. But mostly no. Apologetic gains that emerged from modernity are to a great extent still relevant in late modernity. Indeed, apologetics may be an answer to the problem. I would suggest that a reimagined apologetic would begin with a shift from being primarily philosophical to being more pastoral. Perhaps there also needs to be a shift from the academy to the church. This project may start with a person-focused approach, which will involve an apologetic that views

13 FAITH AND THE ACADEMY: ENGAGING THE CULTURE WITH GRACE AND TRUTH

people differently than it had before. A reimagined apologetic aimed at preventing deconversions in late modernity might start with viewing people as holistic, social, and storied beings. These three frameworks might help us rethink how we do apologetics for those who are thinking about walking away from the faith.

First, people are holistic beings. As James K.A. Smith says, people are not just brains on a stick.10 Humans are not simply Spock-like, hollow people with brains. No, we are not just thinking beings, but we are also desiring beings. We are embodied beings who think with our whole selves, our deepest affections. More often than our thinking determining what we want, what we want determines what and how we think.11 And this is not all bad. Yes, in a fallen world, we have twisted desires and malformed longings, but these are perversions of the truest and best desires that we were born with. As humans in our truest selves, we desire most to love God and love other people in God. Pursuing these desires will make us most happy. As Augustine said in his grand and mature apologetic work, The City of God, “In view of everyone who is at all capable of using reason, it is a certainty that all people want to be happy.”12

Appealing simply to rationalist truth claims will not be the apologetic that works most effectively with real humans today. Instead, we must show those who are tempted to walk away from the faith that the best way to human flourishing and the most authentic way to the good life is through Jesus Christ. No, we are not

saying the best way to get rich or famous is through faith in Jesus, but the way to true happiness and real love is through bending our loves toward what we really want, and what we really want is God’s love. While we are attempting to convince someone intellectually that Jesus Christ rose from the dead, shouldn’t we also connect the resurrection to our human fear of dying and our shared longing for a meaningful life of giving and receiving love? As we are trying to demonstrate rationally that God created the world, shouldn’t we also show how creation is a means God uses to enchant us with a greater vision of His good grace and inspire us to an irrepressible desire to press into His beautiful presence? Perhaps a reimagined apologetic today would begin with a biblical anthropology that will not separate the heart and the mind.

Second, people are social beings. People are embedded in cultures. A dis-enculturated person does not exist. Every person who has ever lived thinks within and responds to the world in which they were formed and are being formed. Individuals have been socialized to feel in their core what is a life lived well and what is a life lived poorly, what it means to succeed and what it means to fail, who is a hero and who is an antihero, what is plausible and what is implausible.13 Charles Taylor has made us more aware that very few, if any, humans actually think in intellectualized frameworks carefully worked out into cognitive conceptions of the world. Instead, he posits that ordinary people “‘imagine’ their social surroundings, and this is not

14

often expressed in theoretical terms — it is carried in images, stories, legends, etc.”14 Thus, we conceive of the world in “social imaginaries.” Normal people do not think in terms of syllogisms and logical proofs; they imagine their worlds through living in certain cultural locations. They develop a “feel” for what is right and what is wrong, what can be believed and what is beyond belief, what makes sense and what is irrational.

Today, these social imaginaries are ever shifting and overlapping. This calls for an apologetic that begins by being with and listening to the other. It invites an apologetic that hears before it tells, that understands before it explains. Prebaked and canned apologetics will not feed the tastes and hunger of people who are looking out on so many banquet tables with seemingly unlimited options to feed their soul. They need friends who themselves are feeding on the eternal food and drink and know how to share this meal with others. In addition, an approach that acknowledges that people are social beings calls for hospitable ecclesial communities who reimagine the world through God-centered worship and biblical teaching, rehabituate lives through liturgical practices, and reconnect people’s common humanity through fellowship and community service. These churches create alternative social imaginaries that are relevant to the everyday situations of its cultural location. Apologetics must shift from the highly individualistic or disconnected

encounters that often occur in the debate arenas or in heated arguments in dorm rooms to a communal project that occurs in worship services, coffee shops, and homeless shelters, an apologetic that shifts from the formal debate stage to the family dinner table.

Recall that the Bible comes to us as a very communal, culturally embedded work where our Savior is born into a certain time and place in history.15 Further, the Bible is made up of culturally meaningful metaphors and myths (not that the events didn’t happen — they did. But they became the stories that defined the community and sparked their imaginations). The Bible comes to us in letters, prayers, poems, prophecies, parables, and stories, all of which are to be experienced and lived within a community of faith. It’s time that our apologetics view people as the Bible does: holistic, social beings.

Third, people are storied beings. We are storytellers by nature. We binge on Netflix stories that run from one season to another. More and more, Bible scholars are coming to recognize that the Bible presents one grand narrative of creation, fall, redemption, and new creation. This is the story that we are living in today and that will reach its telos with the return of Jesus. As Josh Chatraw suggests, Christian apologists should aim to “tell a better story.”16 Christian apologetics today should seek to out narrate competing stories. Today, we should take on questions like, “How is the Christian story more livable and more consistent?” “How does it

15 FAITH AND THE ACADEMY: ENGAGING THE CULTURE WITH GRACE AND TRUTH

make better sense out of our scientific observations and everyday experiences?” and “How is it a better, more beautiful, and truer story?” Curtis Chang insightfully suggests that the approach of Augustine and Aquinas was to (1) enter the challenger’s story, (2) retell the story, and (3) capture the retold tale within the Gospel metanarrative.17 In doing this, we demonstrate for other people that their stories fit best within God’s redemptive story.

This holistic, social, and storied approach includes a vision for tapping into the “catholic” church or, in C.S. Lewis’s terms a “Mere Christianity,” (which is not a minimalist Christianity, but a Christianity centered on the essentials of the Gospel) with its profound intellectual, spiritual, and communal tradition richly resourced enough to address the questions, frustrations, and longings of the Christian contemplating walking away from the faith. Rather than allowing them to abandon their faith, the apologist encourages the wavering believer to travel deeper into the expansive resources of the universal and historic Church.

In this world of fragilized faith, Rhett and Link jumped ship. Initially, Rhett swung into atheism, but that was replaced by an agnosticism with “openness and curiosity.” He lost his appetite for certainty. He still thinks belief in God is very reasonable, the universe is meaningful and has a purpose, which he finds comforting, but doesn't know anything about the God that’s “behind all of this.” His focus has shifted from worrying about what happens after you die to “what happens while you live.” “The only thing I know that I got is this life,” he affirms. He still wants all the morality and meaningfulness of Christianity, without it. He insists that he is still open to revelation, is not a naturalist, and is willing to change his mind. He describes himself as a “hopeful agnostic.”

Link doesn’t want to be an atheist. If God exists, he “wants to be open to that connection.” Overall he has a great aversion to dogmatism and states, “I don’t want to judge — I want to love.” He is “hopeful that he can be hopeful.”18

I hope and pray that they will come back to our wonderful Lord and Savior Jesus Christ and to His beloved Church. I truly wish I had the “silver bullet” answer that would bring them back and keep all others considering deconversion in the fold. It’s not that easy. But I am suggesting that it’s time to reimagine our apologetics based on the Bible and our rich church tradition, an apologetics that equipped Christians to grow and thrive prior to modernity, even in times

when Christianity was not the default position, and offers us vast resources to flourish in this late modern world of fragilized faith. Perhaps apologetics could be a part of the solution.

1 See Dr. Ed Hindson’s article in this issue of Faith and the Academy for a practical and theologically clarifying article on deconversion.

2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1qbna6t1bz

3 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w1AZhlyoD9s

4 Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007).

5 Lesslie Newbigin, Proper Confidence: Faith, Doubt, and Certainty in Christian Discipleship (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1995).

6 See Alasdair MacIntyre, Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press), 1988.

7 Blaise Pascal, Pensées and Other Writings, ed. and trans. Anthony Levi (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 35.

8 Blaise Pascal, Pensées and Other Writings, 158.

9 This would also include Presuppositional Apologetics which emerged primarily in response to modernity, but that article is for another day. See Timothy Paul Jones’s excellent clarifying analysis and careful critique of Cornelius Van Til’s presuppositional apologetic approach in “Apologetics: How Much Intellectual Common Ground Is There Between a Christian and a Non-Christian? Common Notions and Common Ground in the Writings of Cornelius Van Til” https://www. timothypauljones.com/apologetics-is-there-any-common-groundbetween-a-christian-and-a-non-christian/

10 See James K.A. Smith’s You are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit (Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2016) and Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview, and Cultural Formation (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2009).

11 See Jonathan Haidt’s The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion (New York: Vintage Books, 2012).

12 The City of God 10.1

13 See Peter L. Berger’s “plausibility structures” in The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion (1967; repr., New York: Anchor, 1990).

14 Charles Taylor, A Secular Age, 172.

15 See Andrew F. Walls’s chapter, “The Gospel as Prisoner and Liberator of Culture” in The Missionary Movement in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission of Faith (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1996), 3–15 and Miroslav Wolf’s chapter “Distance and Belonging” in Exclusion and Embrace: A Theological Exploration of Identity, Otherness, and Reconciliation, Revised and Updated (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2019), 25–47.

16 Joshua D. Chatraw, Telling a Better Story: How to Talk about God to a Skeptical Age (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Reflective, 2020).

17 Curtis Chang, Engaging Unbelief: A Captivating Strategy from Augustine and Aquinas (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2000), 26.

18 For their perspectives on their faith deconstruction one year later see: Rhett’s Spiritual Deconstruction – one year later: https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=CnYG6x-aOTk Link’s Spiritual Deconstruction – one year later: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=ujtXatJVeN0

17

FAITH AND THE ACADEMY: ENGAGING THE CULTURE WITH GRACE AND TRUTH

Faculty

Contribution

The Letter to the Hebrews and Deconversion: The Struggle for Spiritual Maturity or Security

The meaning of deconversion creates some division in academic circles, but a basic definition may nonetheless be offered. Deconversion may be defined as occurring when individuals reject beliefs, cease participation in relationships associated with those beliefs, and have no foreseeable plans to reconvert.1 For our purposes, deconversion is understood as “a dynamic multi-stage experience of transformative change marked by both liberation from and opposition against religion and a repertoire of symbolic meaning that supports a rapidly growing secular culture.”2 The stages typically experienced include some combination of intellectual doubt, moral criticism, emotional stress (sometimes accompanied by suffering), and disaffiliation from the faith community.3 As John Barbour states: “In one sense, every conversion is a deconversion, and every deconversion is a conversion.”4 In the case of college age students, then, deconversion is often experienced as a transition from religious faith in the worship of God to religious faith in the rejection of God, during which students leave their Christian background for a more humanist position.

The connection of deconversion to the concepts found in the letter to the Hebrews creates more of a problem. Applying definitions anachronistically will often result in conclusions that do not fit the historical narrative of the biblical text. With that in mind, some idea of the problem addressed in Hebrews may be helpful. New Testament scholars differ on the life situation of the recipients of Hebrews, but a general consensus may be represented by the statement that the Christians addressed by this letter are facing a crisis of faith. Some argue that the audience is being tempted to leave the Christian faith to rejoin Judaism as a means to escape persecution, but in general the viewpoint is that some genuine spiritual crisis faces the recipients of this enigmatic letter.5 Space will not allow a detailed account of the occasion, so a brief explanation of the 5 warning passages will be offered: Hebrews 2:1-4; 3:74:13; 5:11-6:12; 10:19-39; and 12:1-29.6

The warning passages describe a concern the author of Hebrews has regarding what his readers are facing — a situation that leads them to consider some kind of spiritual change. In Hebrews 2:1-4, the author warns them against drifting away from God’s revelation in the Incarnation of Jesus. In 3:7-4:13, the concern focuses on rejecting God’s promise and responding with disobedience to God. The incident at Kadesh Barnea illustrates this concern well by showing how the Jews lost the opportunity to enter the land because they refused to listen to or obey God’s Word. This loss is depicted as a lack of rest resulting in a spiritual position of hardness to God. In 5:11-6:12, the readers are warned against spiritual immaturity that could lead to falling away from God’s promise. In 10:19-39, the readers are encouraged to keep faith with each other as a means of encouragement to a continued growth of faith and loyalty to each other. Hebrews 12:1-29 encourages the readers to remain strong in hard circumstances and to follow Jesus’ example of faithfulness when life is hard. These warnings form a structure with the warning against immaturity in Hebrews 5:11-6:12 as the center. This passage receives the bulk of critical consideration due to its emphasis on “falling away” and the “impossibility of restoring to repentance” those who have fallen away. The idea of “falling away” provides a good connection between Hebrews and the concept of deconversion. Hebrews 6:6 includes the words “fallen away” or “falling away” in English translations. The Greek used here is unique in the New Testament but may be defined as “to abandon a former relationship or association, or to dissociate … to fall away, to forsake, to turn away.”7 Some interpreters take this word as “to commit apostasy” which has connotations for leaving the faith or losing salvation. Laying aside the issue of whether or not a genuine Christian can lose salvation or even abandon the faith, we recognize that this word comes from a semantic range meaning variously to fall beside or alongside; to fall or fall in; to fall upon or into; to sin; to occur by chance and opportunity; or to be lost.8 The word is found 57 times in literature

18

Leo Percer Professor of New Testament

John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

beyond the New Testament and is most often used in the sense of “to fall away” or “to fall in/into.” If this definition is accepted, then the language of Hebrews 6 indicates that the danger faced by its readers was a falling away from or an abandonment of their faith. In other words, the author of Hebrews could be seen as warning his readers against a form of deconversion. What was the answer to this danger? The letter to the Hebrews reminds its readers that the danger they faced included the prospect of drifting from the teachings of Jesus, abandoning or responding negatively to God’s promise/command, falling away from the faith due to spiritual immaturity, abandoning the community of faithful believers, and failing to show loyalty to God and to His people in hard times. The answer to avoiding the danger is prescribed as a persevering loyalty to Jesus, His teachings, and His followers. In fact, Hebrews acknowledges that to avoid “falling away,” people need an ongoing discipline and a continuation of fellowship with Jesus and His followers. Spiritual immaturity is the primary cause for “apostasy” in Hebrews, so the proper way to avoid it is the cultivation of spiritual maturity. How does this relate do the concept of deconversion?

Deconversion is often a process that stretches over long periods of time, from several months to many years.10 As a process, it represents a “‘turning from’ and ‘turning to’” which “are alternative perspectives on the same process of personal metamorphosis, stressing either the rejected past of the old self or the present

convictions of the reborn self.”11 So, deconversion may be seen as a spiritual struggle emphasizing a move from a perspective of faith to a perspective of unbelief (a rejection of Christian religion). Deconversion is both a dynamic multi-stage experience of transformative change marked by opposition against the old faith and a repertoire of symbolic meaning that supports a focus that is decidedly more hostile to institutional religion. The people in Hebrews were in danger of turning their backs on Jesus and the Christian faith for some other faith (like Judaism or unbelief). The Jewish faith in the first century enjoyed protections with the Roman Empire, and the early Christian believers did not always enjoy such protection.13 Nonetheless, the problem was not simply security, it was a struggle of belief or faith. The readers of Hebrews struggled to stand firm in a Christian orientation in a hostile environment, and when faced with insecurity as a result of their faith, they were tempted to leave it for a more secure position. That danger led to a lack of loyalty and a process of spiritual immaturity (from the perspective of Hebrews, at least). But the modern danger of deconversion may not be so clearly differentiated.

Experiences of deconversion in today’s world usually include a gradual change away from a faith in institutional religion to a faith in either an agnostic or atheistic worldview. What prompts this gradual change? In both Hebrews and the modern environment, some kind of crisis starts

19

FAITH AND THE ACADEMY:

THE CULTURE WITH GRACE AND TRUTH

ENGAGING

the process. For the Hebrews, the crisis may have been actual persecution, but in our day the crisis is probably intellectual or emotional. Some kind of intellectual doubt or emotional stress plays a role in deconversion.14 A student is confronted with truth claims from two perspectives: a supernatural worldview and a less or non-supernatural worldview. These conflicting truth claims create a crisis of faith that may lead to deconversion. Like the recipients of Hebrews in the first century, the student today may be confronted with the question of whether or not they will remain loyal to a worldview or faith that does not seem to offer security or answers to critical questions. How can we respond to that?

Given the difference in context between the first century setting of the book of Hebrews and modern day, a strong warning narrative may no longer have the desired effect of ameliorating the crisis leading to potential deconversion. In fact, such an approach may come across as dogmatic and somewhat shortsighted. On the other hand, one aspect of Hebrews that Christian educators and ministry leaders need to take to heart is the need to inculcate continued growth toward spiritual maturity. How do we facilitate such a process? One approach would be to deal honestly with the intellectual doubts and questions raised by those who may be in danger of deconversion. Of course, this approach requires an acceptance of the questioner as well as an honest response to the doubts and questions. Like the author of Hebrews, the reasons for deconversion may need to be challenged while also acknowledging that the person raising the questions is still on the path to faith. Encouraging an ongoing loyalty or faithfulness to God requires a foundation of continued loyalty and faithfulness to the person with the doubts and questions.

One part of the deconversion process is a disassociation from the believing community. Sometimes this disassociation is not driven simply by doubts or questions but by a perceived lack of connection to the community. Building a foundation of belonging requires two things: 1) a strong emphasis on a process of discipleship and spiritual growth with knowledge and accountability, and 2) a strong commitment of loyalty to people regardless of their final decision regarding deconversion. The author to the Hebrews often reinforces his readers’ status as believers by statements like: “Even though we are speaking this way, dearly loved friends, in your case we are confident of things that are better and that pertain to salvation” (Hebrews 6:9). In the same passage where he warns them to avoid spiritual immaturity by building a

continual loyalty to God and His Word (based on sound doctrine), the author reminds his readers that he thinks they are on the right track.

To deal with deconversion among college-aged students, educators and leaders need to emphasize both the need for growth (intellectually in doctrine and faithfully in loyalty to God and His people), and the acceptance of those with doubts and insecurities in the context of a community where exploration is safe but discipleship is sure. If skeptics/doubters are not welcome, then they will go somewhere else. If the immature are not challenged, they will not grow. The 21st century finds us in a strange place in Christian education, and yet it is somewhat similar to what a first century author encountered with his church. People are seriously considering whether or not the Christian faith is a good perspective, and Christian leaders are faced with the daunting task of helping them. A focus on building mature believers and accepting doubters (including an honest appraisal of and response to their questions) may be the best response to deconversion today.

1 Lori L. Fazzino, “Leaving the Church Behind: Applying a Deconversion Perspective to Evangelical Exit Narratives,” Journal of Contemporary Religion, 29:2, 251.

2 Ibid., 250.

3 Ibid., 251, and Sergio Perez, Frédérique Vallières, “How Do Religious People Become Atheists? Applying a Grounded Theory Approach to Propose a Model of Deconversion,” Secularism and Nonreligion, 8:3, 2-3.

4 Fazzino, “Leaving the Church Behind,” 251.

5 Luke Timothy Johnson, Hebrews: A Commentary, ed. C. Clifton Black, M. Eugene Boring, and John T. Carroll, 1st ed., The New Testament Library (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2012), 35-36; William L. Lane, Hebrews: A Call to Commitment, (Hendrickson Publishers, 1988), 16, 20-22.

6 Time and space do not allow a detailed exegesis of these passages, so a brief summary of the warnings will be offered instead.

7 David L. Allen, Hebrews, The New American Commentary (Nashville, TN: B & H Publishing Group, 2010), 359.

8 Ibid., 359-360.

9 Lane, Call to Commitment, 25-26.

10 Frédérique Vallières, “How Do Religious People Become Atheists?” 10.

11 Fazzino, “Leaving the Church Behind,” 251.

12 Ibid., 250.

13 Lane, Call to Commitment, 22-24.

14 Frédérique Vallières, “How Do Religious People Become Atheists?” 10-11.

20

Send Us Your STUDENTS

Let

the Center for Apologetics & Cultural Engagement

equip your students to address today’s most challenging social and cultural issues with humility and wisdom through its Student Fellows program.

Students from all academic disciplines can participate. Applications for Spring 2023 are available at LUApologetics.com.

A. Chadwick Thornhill Department Chair of Biblical and Theological Studies John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

A. Chadwick Thornhill Department Chair of Biblical and Theological Studies John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, Liberty University

A REFUGE FOR THE DECONVERTED

It’s no secret that Christianity is declining in the West. According to the Pew Research Center, in the United States, the percentage of adults who consider themselves Christians has fallen 12 percentage points in the last decade, standing at 65%. In contrast, the percentage of the religious unaffiliated, often referred to as the “nones,” has risen 9 percentage points, accounting for 26% of U.S. adults. This decline is occurring across Christian denominations as well. In some ways, this shift is a generational one, with 84% of the Silent Generation and 76% of Baby Boomers self-identifying as Christian, and just 49% of Millennials.1 And “deconversion” stories, stories of those formerly identifying as Christian who now no longer do, are, in fact, most prominent in young adults.2

The portrait of decline can be painted from several angles. As John Marriott summarizes,

[P]erhaps the most concerning statistic comes from the Pinetops Foundation who, in 2018, claimed that over the next thirty years Christian affiliation in the U.S. will decline by one million per year. Which means that between 30 and 42 million young people raised in Christian families and who call themselves Christians will say they are not by 2050.3

Globally, Christianity’s “decline” is much more moderated, dropping from 34.5% in 1900 to 32.3% in 2020. The global population of Christianity thus has shifted largely away from its former “center” in Europe and North America to Latin America, Africa, and Asia.4 The future of Christianity seems largely a global one.

In the West, however, “cultural Christianity” is on its way out, and as the Christian population decreases, its cultural influence will as well. The reasons for this decline, as one might expect, are multi-faceted, and our late modern environment, with its radical “expressive individualism,” certainly provides no small influence in this trend.5 Research has focused

in recent years on why people deconvert. According to Streib and Keller, most cases of deconversion show the presence of the following contributing causes, with varying weight ascribed within individual experiences:

(1) loss of specific religious experiences; (2) intellectual doubt, denial, or disagreement with specific beliefs; (3) moral criticism; (4) emotional suffering; and (5) disaffiliation from the community.6

While Christian apologists since the Enlightenment have focused primarily on the intellectual obstacles to faith, it is clear from these contributing causes that we need a “whole-person” approach to dealing with religious doubts. Relational, experiential, and emotional catalysts may contribute as much, if not more so, to the loss of faith in individuals than questions they have about the intellectual merits of the faith.

In the wake of the #MeToo and #ChurchToo movements, a rise in the corrosion of trust in religious institutions is also a significant contributing factor to deconversion.7 While, from an intellectual perspective, one might be able to separate the offenses of religious leaders from the validity of the truth claims a religion might make, in practice for those affected by abuse and mistreatment in a religious setting, the religion itself may be seen as the source of personal suffering.8 In other words, we as much show the nature of the faith with our actions as we tell what it is like with our words. And if our showing and telling are incoherent (examples of which continue to rapidly accumulate), substantial resistance to and rejection of the faith will continue. It is certainly to our shame to offer such a meager visible witness of the great love of our God demonstrated in the good news of Jesus Christ.

Is there a way out of this decline? Can the tide of deconversion in the West actually be turned? The statistical predictions certainly do not favor this outcome. This should not diminish, however, the burden each individual Christian, and Christian

22

Faculty Contribution

leaders especially, should feel to being an agent of change. Rather than dig in our heels in outrage at the cultural circumstances we find ourselves in, a substantial change in the power of our witness may come if the Church heeds the call both to selfexamination and to re-centering itself on the priorities of King Jesus.

Marriot offers this advice: “To avoid setting up believers for a crisis of faith Christians of all stripes must reflect on the kind of faith they are passing on to those they are ministering to.”9 In other words, have we, in our understanding of the Church’s mission, actually in practice prioritized what Jesus commanded? Have we passed on a faith that travels beyond mere belief to embodied faithfulness? Have we cultivated love for God as our first order of business and love for neighbor as the essence of our mission? If we have not, let us repent. Let us ask God for forgiveness. Let us realign our priorities to the priorities Jesus himself has given us.

What would it mean for us, then, to love the “deconverted?” To love the “nones?” If love, as McKnight has defined it, is a “rugged commitment to the good of another,” to be “with them” and “for them” in the process of seeking Christlikeness,10 then how does the Church operate in this fractured cultural environment on the basis of love?

It first means giving real space, empathy, and care to the personal pain each one of our neighbors faces, especially where the Church has been complicit in this pain. As Nouwen writes,

Our suffering and pains are not simply bothersome interruptions of our lives; rather, they touch our very uniqueness and our most intimate individuality. The way I am broken tells you something unique about me. The way you are broken tells me something unique about you. ... Our brokenness is always lived and experienced as highly personal, intimate, and unique. I am deeply convinced that each human being suffers in a way no other human being suffers.11

To love our neighbor in this way means to be “with” them in their pain, not excusing it as something “just emotional” for the real obstacles to faith, but seeing their pain as a deeply personal dimension of their own humanity. Too often in our combative stance toward all things secular, we overlook that those whom we have postured as our enemies are also human and, as such, objects of God’s immeasurable love.11

As it pertains to the deconverted, have our friendships with them ended when they leave the four walls of the church? Or ought we pursue friendship as a means

23 FAITH AND THE ACADEMY: ENGAGING THE CULTURE WITH GRACE AND TRUTH

of love in spite of, or perhaps even because of, their rejection of the faith? Can we truly love our neighbor in this way, not as a means to an end but as the essence of our mission? Can we help them to see God’s love through our love for them in the midst of their pain? Nouwen again is insightful:

I want to say to you that most of our brokenness cannot be simply taken away. It’s there. And the deepest pain that you and I suffer is often the pain that stays with us all our lives. It cannot be simply solved, fixed, done away with. ... What are we then told to do with that pain, with that brokenness, that anguish, that agony that continually rises up in our heart? We are called to embrace it, to befriend it. To not just push it away ... to walk right over it, to ignore it. No, to embrace it, to befriend it, and say that is my pain and I claim my pain as the way God is willing to show me His love.12

If love is the essence of our mission, then love must be our first thought toward how we navigate a deeply fractured world. To be discipled in the way of Jesus means to be discipled in the way of love — both love for God and love for neighbor as oneself. Has our discipleship led us to love as our reflex? Has love become our instinctive response to the world? This is truly a battle against our flesh, which naturally seeks payback, retaliation, and “winning” against our so-called enemies.

As Chesterton famously said long ago, “[T]he great ideals of the past failed not by being outlived, but by not being lived enough… The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting. It has been found difficult; and left untried.”13 Indeed, too often this way of love as mission has been left untried. It was this kind of love in the early church that garnered its cultural influence. As the Roman emperor Julian once remarked, it was the benevolence of the Church toward strangers and the holiness of their lives that most expanded their influence throughout the Empire.14 If we find ourselves bothered by our cultural circumstances, and in the decline of Christianity in the West, it seems to me the best place to start is in loving our neighbors, deconverted or not.

24

1 Pew Research Center, “In U.S., Decline of Christianity Continues at Rapid Pace,” last modified Oct. 17, 2019, https://www.pewforum. org/2019/10/17/in-u-s-decline-of-christianity-continues-at-rapidpace/.

2 “Most of those who decided to leave their childhood faith say they did so before reaching age 24, and a large majority say they joined their current religion before reaching age 36. Very few report changing religions after reaching age 50” (Pew Research Center, “Faith in Flux,” last modified February 2011, https://www.pewforum. org/2009/04/27/faith-in-flux/).

3 John Marriott, “Deconversion: The All-Or-Nothing Fallacy,” Christian Scholar’s Review, last modified June 30, 2021, https:// christianscholars.com/guest-post-deconversion-the-all-or-nothingfallacy/.

4 Gina A. Zulro and Todd M. Johnson, “Is Christianity Shrinking or Shifting?,” Lausanne Global Analysis, 10:2 (2021): https://lausanne. org/content/lga/2021-03/is-christianity-shrinking-or-shifting.

5 Barbour cites the rise in pluralism and individualism as contributing factors (John D. Barbour, Versions of Deconversion: Autobiography and the Loss of Faith (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994), 51).

6 Heinz Streib and Barbara Keller, “The Variety of Deconversion Experiences: Contours of a Concept in Respect to Empirical Research,” Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 26 (2004): 181-200.

7 According to a recent Pew study, deconversion most often occurs because of a change in religious or moral beliefs, or a lack of trust in religious institutions (Pew Research Center, “Faith in Flux,” last modified Feb. 2011, https://www.pewforum.org/2009/04/27/faithin-flux/).

8 “…that they became unaffiliated, at least in part, because they think of religious people as hypocritical, judgmental or insincere. Large numbers also say they became unaffiliated because they think that religious organizations focus too much on rules and not enough on spirituality, or that religious leaders are too focused on money and power rather than truth and spirituality” (Pew Research Center, “Faith in Flux,” last modified Feb. 2011, https://www.pewforum. org/2009/04/27/faith-in-flux/).

9 John Marriott, “Deconversion: The All-Or-Nothing Fallacy,” Christian Scholar’s Review, last modified June 30, 2021, https:// christianscholars.com/guest-post-deconversion-the-all-or-nothingfallacy/.

10 Scot McKnight, “The Four Elements of Love,” Jesus Creed, last modified May 1, 2015, https://www.patheos.com/blogs/ jesuscreed/2015/05/01/the-four-elements-of-love/.

11 Henri Nouwen, Life of the Beloved (New York: Crossroad, 1992), 89-90.

12 Henri Nouwen, You Are the Beloved (New York: Crown Publishing Group, 2017), 310.

13 G.K. Chesterton, What’s Wrong with the World? (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1912), 48. Or, As McKnight suggests, we ought to name our enemies, and then ask ourselves how we are loving them (McKnight, “The Four Elements of Love,”https://www.patheos.com/ blogs/jesuscreed/2015/05/01/the-four-elements-of-love/).

14 Cited in Matt Crawford, “The Compassion of Early Christians,” Bible Mesh, last modified Feb. 7, 2020, https://biblemesh.com/blog/ the-compassion-of-early-christians/.

25

Keith Lahikainen Associate Professor of Psychology School of Behavioral Sciences, Liberty University

CONCEPTUALIZING THE PSYCHOLOGICAL DIMENSIONS OF DECONVERSION

One of the heaviest burdens a Christian can come to bear is when a loved one walks away from the faith. Despite the eternal significance of such a change for the one who falls away, the experience is not exclusively personal. Believing family and friends are often left picking up the pieces, grieving over the loss of communion and the spiritual fate of the deconverted (2 Peter 2:21). Believers may come to feel betrayed (Matthew 24:10) and left wrestling with questions of “how” and “why” their beloved lost faith in Jesus, or whether the individual ever truly believed. Further still, they may struggle with feelings of guilt, wondering whether they could have done something different to alter the deconversion. Such questions can take an emotional toll on even the most mature Christians. Yet an individual’s deconversion rarely happens overnight. There is most often a notable progression from when first doubts arise to when the final exodus from faith occurs. The problem is that many believers are ill-equipped to identify the severity and progression of the deconversion process. Therefore, having a conceptual framework to identify the outward signs of inner changes taking place would be beneficial. Coming to understand and engage a person who is wandering from the faith could help to save their very soul, which is something believers are called to do (James 5:20). The following essay proposes that there are discernable psychological and behavioral markers that emerge in faith deconversion which are common in people who change. Many of these markers make it possible to recognize the deconversion process in individuals and offers guidelines for engaging them in ways that are most likely to facilitate positive change.

As the divine creator of human psychology, God works holistically through spiritual and psychological processes in turning people toward Him and in allowing human rebellion. Although conversion to faith and falling away from faith (i.e., deconversion) are ultimately spiritual phenomena, examining the psychological dimensions of these changes can provide

a deeper understanding of the processes involved as well as the possibility of influencing such outcomes. Prospectively, we would be able to psychologically assess the likelihood of an individual’s faith status through the conveyance of belief via language and faith-resonant behaviors. These conceptual parameters align with God’s Word, which asserts, “For with the heart one believes and is justified, and with the mouth one confesses and is saved.” (Romans 10:10, ESV) and “Whoever abides in Me and I in him, he it is that bears much fruit, for apart from Me you can do nothing” (John 15:5, ESV).1 It is evident from these passages that some form of both cognitive and behavioral assent is manifest in the believer’s transformation. Additionally, the book of James emphasizes the power of the tongue and inextricable connection between the professing of faith and one’s behavior, proclaiming, “For as the body apart from the spirit is dead, so also faith apart from works is dead.” (v. 2:26). These factors are not the cause of faith but rather the manifestation of its presence. Although we cannot determine someone’s faith with absolute certainty, we can observe and interact with the psychological markers of such changes in the person’s language and behavior.

Psychological Reactance

Despite the apparent unraveling of Peter’s professed faith in Matthew 16:16 to his thrice denial in chapter twenty-six, such a dynamic can be understood in terms of psychological reactance. Reactance is an averse motivation to counter perceived pressure to align oneself with external standards. For example, expectations to change placed upon an individual when they are not ready could generate resistance. The more pressure that is applied to conform, the greater the resistance to change. The Transtheoretical Model of Change (TTM) has become widely used in countering psychological reactance in clinical settings. Psychologists James Prochaska and Carlo DiClemente

26

Faculty Contribution

developed the TTM to classify behavioral change processes in the initiation of, and recovery from, substance abuse.2 The model has since been used in a variety of contexts to address change-related issues ranging from diet and nutrition to medication compliance and bereavement.

The practicality of the TTM resides in its description of six distinct stages, all of which are discernable and open to particular methods for facilitating change. Therefore, the TTM provides a functional framework for understanding and working with the psychological markers and processes of change that accompany faith deconversion. According to the TTM, change does not happen by accident, nor is it likely to occur spontaneously outside the contextual indicators described in each stage. Most individuals in the process of deconversion exhibit a progressive number of verbal and behavioral markers well before they leave the faith. It would be the rare instance that one goes to bed a believer in Jesus and wakes up a nonbeliever. Often in retrospect, a “faith autopsy” reveals numerous signs and warnings of someone’s deconversion in stages. Progression through the stages is not necessarily linear but rather a fluid spiral in which individuals can move back and forth across the stages. Despite the potential variability in movement, knowing the stage status of an individual equips those serving the person in counsel to use an approach that is conducive to facilitating change versus reactance.

First Stage: Precontemplation

The first stage of the model is precontemplation, in which there is no desire or intention to change. Individuals in this stage would not be considering a need to change and may even be unaware of issues that exist outside their current beliefs. From the perspective of someone moving from faith to deconversion, we would describe individuals who profess faith in Christ while exhibiting the “behavioral fruit” of such faith without consideration of change to be in precontemplation. This does not, however, preclude the potential to experience occasional doubt or struggle with reconciling aspects of faith and behavior. Rather, precontemplative individuals will actively resist attempts to challenge their beliefs or to be proselytized to a new faith. Nonetheless, precontemplators may also include individuals who have grown up in a Christian environment and who have cognitively internalized a “cultural faith.” As such, they have not developed a true saving faith in Jesus but lack an awareness or desire to explore alternative beliefs. Like those with a saving faith, these individuals would be apt to resist overt efforts to dispute their beliefs. Nevertheless, they would be vulnerable to more subtly progressive tactics that aim to raise their consciousness regarding other belief systems. Since they have internalized

27

FAITH AND THE ACADEMY: ENGAGING THE CULTURE WITH GRACE AND TRUTH

an external model, greater awareness can lead to selfreevaluation in which one’s own values and behaviors are examined in light of new knowledge. This process is likely to be accompanied by an environmental reevaluation where the individual assesses the role of others in shaping their beliefs. Social structures supporting the change toward deconversion (e.g., nonbelievers or fellow “believers struggling with their faith”) drive the course of change. Nonetheless, these processes are not inherently negative and do not necessarily lead to deconversion. On the contrary, when intentionally used in the context of discipleship, it is argued that they can be leveraged to develop or strengthen faith.

Second Stage: Contemplation

Those precontemplators who move on to actively consider change by seeking out information and reassessing the congruence of their spiritual beliefs and behaviors are considered to be in the contemplation stage. Though contemplators are not ready to change, through exploration of alternative views and burgeoning dissonance they may begin to experience significant distress in regard to their faith. Furthermore, contemplators might express an overt curiosity about spiritual matters and perceived challenges to faith in Christ. In their most honest moments, such individuals may express ambivalence about their faith or about making changes. The potential fear and anxiety that can be generated through contemplating change can leave them “stuck,” unable to grow in their faith or to walk away. Often left waiting for some striking event to shift them in one direction or another, they may be hesitant to share the depth of their struggles. Making room for safe and honest conversations that include a respect for the doubts they have while facilitating the selfidentification of positive faith features can be helpful. Although the goal is to help contemplators resolve their ambivalence in the direction of faith in Jesus, resolution can progress the other way.

Third Stage: Preparation

When an individual resolves their ambivalence in the direction of leaving the faith, they would be considered to be in the preparation stage of change. Although a decision has been made to change, the individual has not yet taken action to leave the faith, announce their nonbelief publicly, or dissolve relationships with believers. However, there is a marked increase in their focus on the future, accompanied by a

diminished focus on past connections to their faith. Here the individual spends more energy on preparing for change than weighing out the pros and cons of their decision. Others may notice a dramatic relief from the distress the individual was expressing prior to making a decision. Additionally, preparers may talk openly and positively about those who have left the faith and gauge the reaction of others. Efforts to engage those preparing to leave the faith should focus on open and honest recognition of the change taking place. Preparers will have developed confidence in their decision to walk away but are still likely to be experiencing anxiety about making the “right” decision. Therefore, supportive discussions emphasizing the potential dire consequences of their decision are warranted. Oftentimes, believing loved ones may perceive this stage as their last opportunity to exert pressure on the individual to not recant their faith. Or, they may unconditionally accept the change taking place in hope of not driving the individual further away. The discipleship goal here is to shift back to contemplating faith in Jesus, along with the reemergence of authentic ambivalence. Although loved ones may be tempted to “push for action” (i.e., return to professed faith), it may generate reactance or a false confession in preparers. Great care should be taken in that a successful return to contemplation is likely to include a recurrence of dissonance and distress.

Fourth Stage: Action

Those who follow through with leaving the faith are seen as taking action. The action stage is characterized by a firm commitment to their decision, a marked change in their social relationships and the environments in which they associate, as well as the possible termination of relationships not supporting their change. Those entering the action stage may even become exuberant advocates of nonbelief, assertively countering arguments for faith and opposing believers on principle alone. This stage can be the most disheartening for believing loved ones. Attempts to overtly counter the new belief systems are likely to generate reactance, whereby the individual “digs deeper” into their position. If the new position is sustained and a new identity firmly developed around their nonbelief and nonbelieving social support systems, the individual would be considered in the final maintenance stage of change and deconversion.

28

Fifth Stage: Maintenance

In the last stage of deconversion, we would invert the model so that those who deconvert are also conceptualized as residing in the first stage of faith development. The precontemplation stage of faith development can be described as spiritual blindness, hardness of heart, or a state of being completely unaware that one is spiritually dead and in need of Jesus. Hence, efforts to engage precontemplators as if they are one step away from returning to faith are less likely to succeed. Rather, raising their awareness by asking questions that elicit potential change talk and arousing emotions about the challenges of their nonbelief would be more conducive to change. Efforts to encourage ambivalence regarding their nonbelief while respecting their decision making would be the next step in helping them transition to the contemplation stage of faith.

It must be clearly stated that the proposed use of the TTM will not identify an individual’s true faith, nor will it provide a means of generating faith in Christ where it does not otherwise exist through the work of the Holy Spirit. In addition, the use of the model is not meant to replace or compete with biblical approaches used to reconcile deconverted individuals (e.g., prayer, evangelism, or discipleship). Rather, the TTM can be used to conceptualize current levels of faith development or deconversion. It also provides a framework for understanding the needs and characteristic behaviors of individuals in each stage. Further still, the TTM offers guidance for engaging individuals with stage-appropriate interventions, which are likely to maximize their effectiveness. Regardless of whether truly saved individuals can theologically fall into apostasy, the TTM honors the autonomy of persons and the work of the Holy Spirit in bringing people to genuine faith. It is relationally focused and facilitates a response from the individual through the necessary involvement of others. The approach focuses on meeting individuals where they are, not where we desire them to be. And in doing so, it can promote spiritual growth and change in the facilitating believer who attempts to bring back those who have wandered from the truth (James 5:19-20).

1 Unless otherwise noted, all biblical passages referenced are in the English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2008).

2 James O. Prochaska & Carlo C. DiClemente, “Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change,” Psychotherapy, 19, no. 3, (1982): 276-288. doi:10.1037/h0088437.

2 James O. Prochaska & Carlo C. DiClemente, “Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change,” Psychotherapy, 19, no. 3, (1982): 276-288. doi:10.1037/h0088437.

BEFORE YOU LOSE YOUR FAITH: AN INTERVIEW WITH IVAN MESA

Recently, Ivan Mesa, editorial director for the The Gospel Coalition, took time to have a conversation with Jack Carson, the new executive director for the Center for Apologetics & Cultural Engagement here at Liberty.

Carson: What made you decide to edit the book Before You Lose Your Faith?

Mesa: Like many, I kept hearing public deconversion stories over the years that would sadden and discourage me. But it wasn’t until I heard of Rhett and Link — the duo behind Good Mythical Morning (their daily YouTube show with more than 16 million subscribers) and Ear Biscuits (their podcast) — that I began thinking of how to positively address this phenomenon. The two of them — who as of Dec. 2020 are the fourth-highest YouTube earners, making $20 million a year — shared about how they moved from Cru staffers and missionaries to unbelievers — or, as Rhett now describes himself, a “hopeful agnostic.” The comedians had for years been a staple in many homes with children and young adults (with videos ranging from “epic” rap battles to testing the world’s hottest peppers to getting shot with Nerf guns), so we kept hearing from parents and youth and campus ministry leaders that their public announcement unsettled the faith of many young people.

Carson: What is deconstruction, and why does it seem to be a growing trend in the world today?