Real-Life Sociology: A Canadian Approach

Second Edition Anabel

Quan-Haase

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/real-life-sociology-a-canadian-approach-second-editi on-anabel-quan-haase/

This image shows the cover of Real-Life Sociology: A Canadian Approach

Real-Life Sociology

A Canadian Approach

Anabel Quan-Haase | Lorne Tepperman

Second Edition

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in Canada by Oxford University Press

8 Sampson Mews, Suite 204, Don Mills, Ontario M3C 0H5 Canada www.oupcanada.com

Copyright © Oxford University Press Canada 2021

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First Edition published in 2018

All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Permissions Department at the address above or through the following url: www.oupcanada.com/permission/permission request.php

Every effort has been made to determine and contact copyright holders In the case of any omissions, the publisher will be pleased to make suitable acknowledgement in future editions.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Real-life sociology : a Canadian approach / Anabel Quan-Haase, Lorne Tepperman

Names: Quan-Haase, Anabel, author | Tepperman, Lorne, author

Description: Second edition | Includes bibliographical references and index

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20200405691 | Canadiana (ebook) 20200405721 | ISBN 9780199037223 (softcover) | ISBN 9780199037308 (EPUB)

Subjects: LCSH: Sociology Textbooks | LCSH: Sociology Canada Textbooks | LCSH: Canada Social conditions 21st century Textbooks. | LCGFT: Textbooks.

Classification: LCC HM586 .Q35 2021 | DDC 301.0971 dc23

Cover image: © Simone Golob/Offset com

Cover design: Laurie McGregor

Interior design: Sherill Chapman

Oxford University Press is committed to our environment. Wherever possible, our books are printed on paper which comes from responsible sources

Printed by LSC Communications, Inc., United States of America

1 2 3 4 24 23 22 21

Created on: 09 April 2021 at 11:26 a.m.

Preface

Anabel Quan-Haase

Lorne Tepperman

The job of any textbook is to invigorate an old field (or discipline), giving it new life. If successful, the present book does this by highlighting ways that the field cultivated over centuries in various ways, for a variety of historical reasons can help us better understand the present day, and perhaps even the future.

In Real-Life Sociology, we have tried to show how the present-day world has been shaped by rapid developments in science and technology, and how, in turn, social forces have brought science and technology to fruition. As we will see, science and technology have flourished at particular times and places, but never as much as today. As a result, many aspects of daily life how we play, work, and learn have been transformed by technological innovation by computers, robotics, the internet and social media, modern medicine, space-age modes of transportation, and household appliances that would have been unimaginable only a century ago, to name a few of these “miracles.”

Sociologists are becoming increasingly aware of the rapid scientific and technological transformations that are unfolding. This provides a unique opportunity for understanding and predicting how all of these technological marvels will affect our personal lives, institutions, and social norms. Sociologists are developing new methodologies to study how people communicate and interact in a world mediated by mobile phones, social media, and online communities. This is an exciting time, as many new questions surface and new ways of looking at the social world emerge. But it is also a time of post-truth, unprecedented forms of alienation and inequality, and rapid transformations in many domains of life.

Futurologist Alvin Toffler said in the 1970s that we were all at risk of suffering “future shock” the result of a speeded up pace of life and unparalleled social change. There is some evidence Toffler was right: for example, we see high and growing rates of anxiety,

depression, and addiction in many parts of the world, especially among our young people. In some part, these issues are a response to the stress produced by change and uncertainty. Yet humanity has always struggled and will continue to struggle with rapid social change. It is our hope that this book, which sets some of the most newsworthy and important social changes in a sociological context, will help students overcome “future shock” by adapting to the future as it unfolds.

So, with that thought in mind, we hope our readers find this “real-life approach” to present-day society exhilarating and useful. Let us know what you think.

Acknowledgments

It takes a village to raise a child and a community of helpers to write a book as wideranging as this one.

At the University of Toronto, a variety of undergraduate researchers helped Professor Tepperman research, write, and edit this book. These excellent research assistants included Ivana Avramov, Teodora (Teddy) Avramov, Gary Guinness, Richard Kennedy, Darya (Dasha) Kuznetsova, Ashley Ramnaraine, Jacqueline Wing Yang Siu, Sylvia Urbanik, Alice Wang, and Jiaqi Wang. They were headed up by the amazing Zoe Sebastien, who has now gone on to excel in the study of law. So, we send thanks to all of our Toronto undergraduate and graduate helpers for their insights and efforts. At Western University, Professor Quan-Haase benefited greatly from the help of students Isioma Elueze, Chandell Gosse, Kelsang Legden, Ryan James Mack, Victoria O’Meara, Abdul Malik Sulley, and Carly Williams for the first edition, and for the second edition, Dennis Ho, Alice Hwang, Claudia Jiang, Olivia Lake, Kristen Longdo, Charlotte Nau, and Sananda Sahoo.

We were also helped by a number of anonymous reviewers who provided wonderful and instrumental suggestions for improvement at various stages of development. Big thanks go, then, to our reviewers:

• Anton Oleynik, Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador

• Ataman Advan, Simon Fraser University

• Kelsey Leonard, Six Nations Polytechnic

• Marcella Cassiano, University of Alberta

• Deanna Behnke-Cook, University of Guelph

• Angela Aujla, Georgian College

• Ondine Park, MacEwan University

as well as several who chose to remain anonymous.

Last and certainly not least, we want to thank the marvellous people at Oxford

University Press who supported our work throughout with great dedication. They include Darcey Pepper, who, as former acquisitions editor, helped us launch the project. Amy Gordon, our developmental editor, provided a steady flow of good humour and countless invaluable suggestions. In these ways, Amy made our job genuinely enjoyable, even at times when we were struggling. So, thank you, Amy. We also thank Leslie Saffrey, our copy editor, who was extraordinarily thorough and helpful; her edits were invaluable and made sure this text is the best it can be. Finally, we thank Lisa Ball, who saw the book safely through final stages of the production process.

We also thank our colleagues at the University of Toronto and Western University for their input and support. Finally, we thank our parents, who through their hard work made generational upward mobility, and in that way the writing of this book, a reality.

Anabel Quan-Haase Western University

Lorne Tepperman University of Toronto

Publisher’s Preface

Anabel Quan-Haase

Lorne Tepperman

Society shapes our everyday lives in ways we often cannot see unless we exercise our sociological imaginations. It is our hope that Real-Life Sociology will not only teach you to engage your sociological imagination but will also help you understand why this skill is so important, particularly in today’s globalized and technology-driven world.

In preparing this new edition, we retained our one paramount goal: to produce the most relatable, comprehensive, and dynamic introduction to sociology available to Canadian students. We hope that as you browse through the pages that follow, you will see why we believe the second edition of Real-Life Sociology is the most exciting and innovative textbook available to Canadian sociology students today.

What Makes This a One-of-a-Kind Textbook

A Canadian Textbook for Twenty-First Century Canadian Students

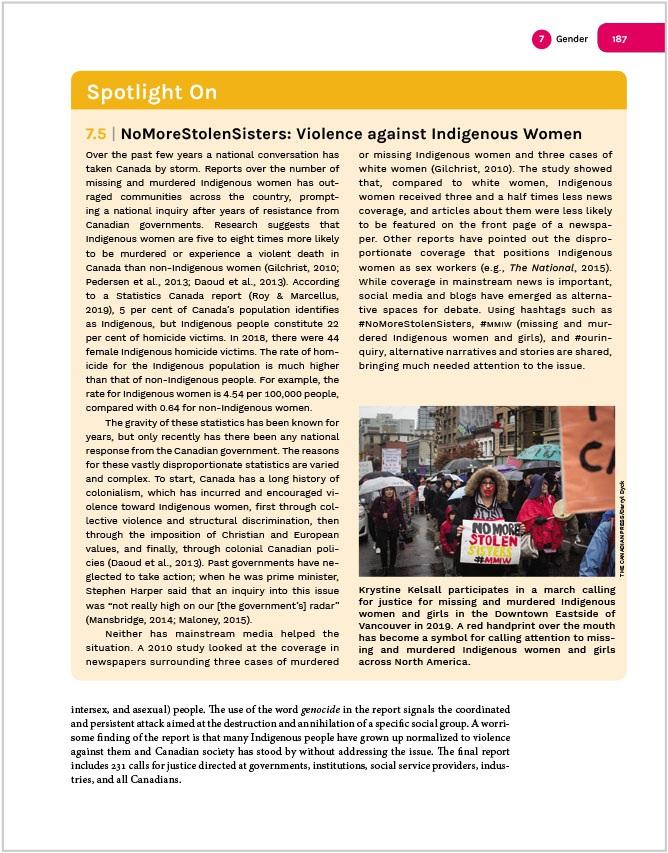

Written by Canadians for Canadians, Real-Life Sociology highlights the realities of Canadian society as it exists today: it uses recent major events with sociological drivers and effects such as #NoMoreStolenSisters, the COVID-19 pandemic, Black Lives Matter protests, and many more to illustrate sociological concepts.

An Intersectional Approach

While the chapters in Real-Life Sociology are organized according to the traditional

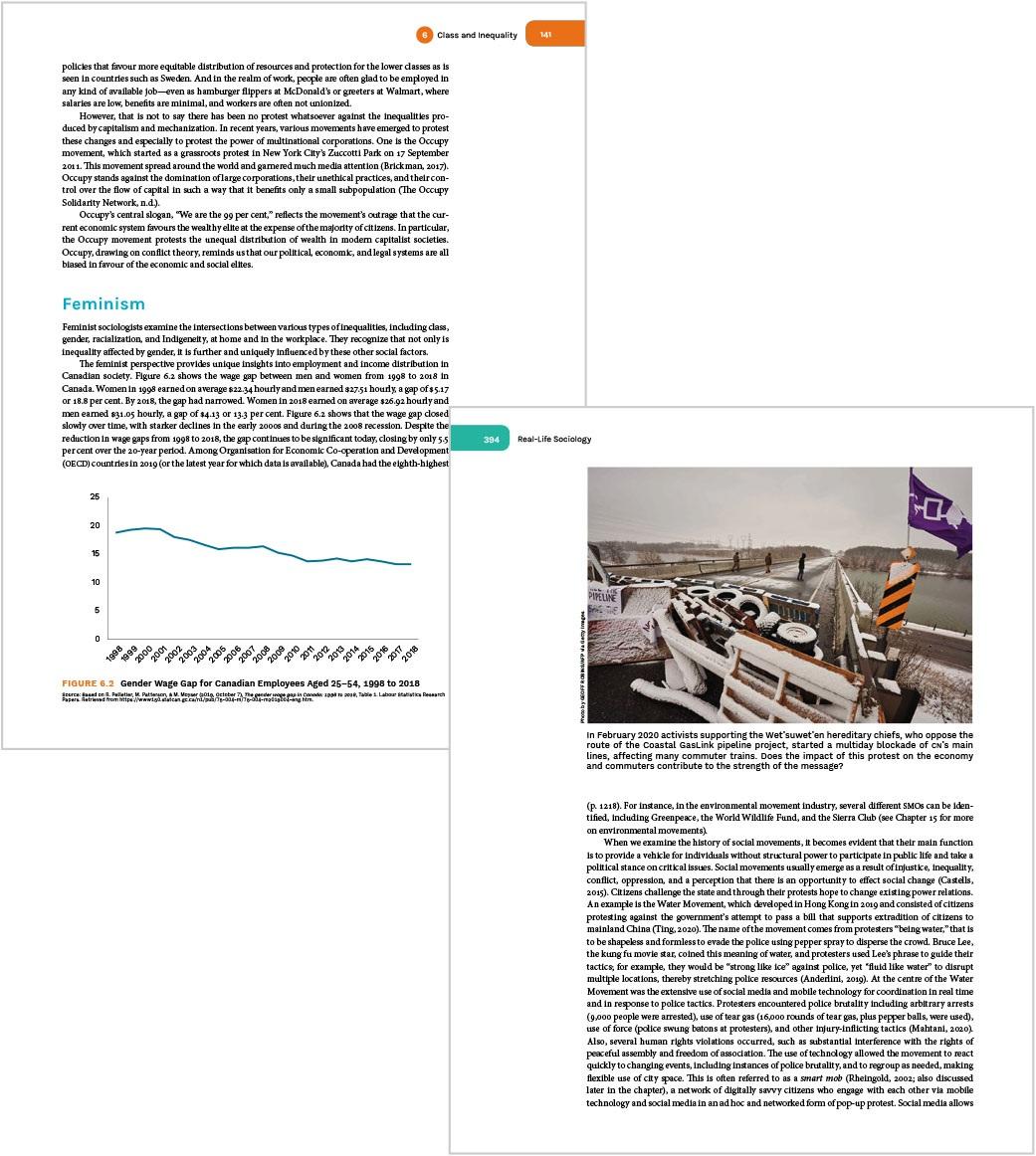

separation of gender, racialization, and class, the concept of intersectionality has been implemented throughout the book. Students will better understand the intersections of racialization, gender, gender presentation, citizenship status, Indigeneity, sexuality, disability, and class when discussing topics such as the wage gap, suicide statistics, educational attainment, social mobility, and climate change.

Coverage of Technology and the Digital Society

In addition to Anabel Quan-Haase’s expertise on the social changes led by information and communication technologies, every chapter includes powerful and accessible case studies and examples that show how technology and digital media are changing our everyday lives and who these changes are leaving behind.

A Visual, Thought-Provoking Presentation

Students are encouraged on every page to adopt a sociological imagination in order to see the sociology in everyday life. Carefully chosen photos and captions, provocative Time to Reflect questions that link back to chapter learning objectives, and end-ofchapter review and critical thinking questions invite readers to apply theory to their everyday lives.

Case Studies and Compelling Viewpoints

In addition to the Time to Reflect boxes, Real-Life Sociology features five other types of boxes that illustrate sociological concepts by highlighting issues, events, and ideas at the centre of contemporary life. Case studies with questions and answers at the end of each chapter were written by Sonia Perna, instructor, Southern Alberta Institute of Technology.

Think Globally

Think Globally boxes apply a global perspective to the concepts in the chapter, either comparing Canada with the world or bringing up key issues in other countries that illustrate the chapter concepts

2 2 Call for a Global Public Sociology

3.3 The Law of Jante

4.4 Relocation and Gendered Social Scripts

5.2 Human Trafficking and Sexual Exploitation 6 5 Closing Global Inequality through Digital Education: One Laptop per Child 7.3 Labour Participation of Women Worldwide 8.5 Diaspora Communities Build and Preserve Social Ties Online 9 1 Science, Technological Progress, and theAlarming Longevity Gap 9.4 COVID-19 andAsylum Seekers at US and Canadian Borders 12.3 The Cost of WorkplaceAccidents 13 1 Can the Digital Divide Be Used for Religious Social Control? 14.2 Social Media as Citizen Journalism 15.3 Who Will (Likely) Be the Main Victims of COVID-19? 16 3 M-15 or Los Indignados: Networked Mobilization Theory in Everyday Life Theory in Everyday Life boxes introduce theories and theorists and apply their work to the real world. 1.1 Founders of Sociology 2.1 Representations of Community Policing 3 2 Gender Scripts 4 2 Residential Schools: Resisting Total Institutions 6.3 The Digital Divide and Differential Benefits from Digital Media 7.1 The Work of Judith Butler 8 1 Two Examples of Racial and Ethnic Discrimination 9.2 Access to Health Services 11.4 AFeministApproach to Online Education 12 4 H G Wells

Reginald Bibby

2.0

3 Online Gaming and Social Construction

Facebook

Do

toAsk for Consent to Study Facebook Interactions?

Social Media Reshaping Canadian Culture

Context Collapse on Social Media

1 Challenging the Norm

ANew Elite of Technological Visionaries

Gigi Gorgeous

4

of a Feather

in Digital Space

4

and the Time Spent on Housework

Plagiarism: Its Causes and Consequences

The Shared, Electric, Self-Driving Car

2 Religion? We’ve GotApps for That

Participating in Remix Culture

Technotrash

1 Smart Mob: Water Movement

Divide

13.3

14.5 Understanding and Measuring Digital Literacy Sociology

Sociology 2.0 boxes outline contemporary examples as case studies that are relevant for students, particularly related to science and technology 1

2.5 The

Experiment:

Researchers Need

3.1

4.5

5

6.2

7.2

8

Birds

Flock Together

10

Technology

11.5

12.1

13

14.3

15.4

16

Digital

Digital Divide boxes discuss inequality in a digital and technology-driven age, relating the concepts in the chapter to modern inequality.

1.4 Gamergate

2.3 Statistics Canada’s Strategy for Ensuring Full Enumeration of Indigenous People in Canada

3.5 TechnologicalAcceptance

4 3 Masculinities on Instagram

5.4 OlderAdults and Cybercrime

6.1 Disciplining Digital Play in Youth Culture

7 4 Initiatives to Promote the STEM Curriculum to Girls

8.2 LinkedIn Profiles as Markers of Identity: To Erase or Not?

10.5 Can Older Parents Connect with Cyber-Obsessed Kids?

11 3 Making TechnologyAccessible

12 5 Are New Information and Communication Technologies Creating a “Digital Skills Gap”?

13 6 Internet Use and the Decline of Religion

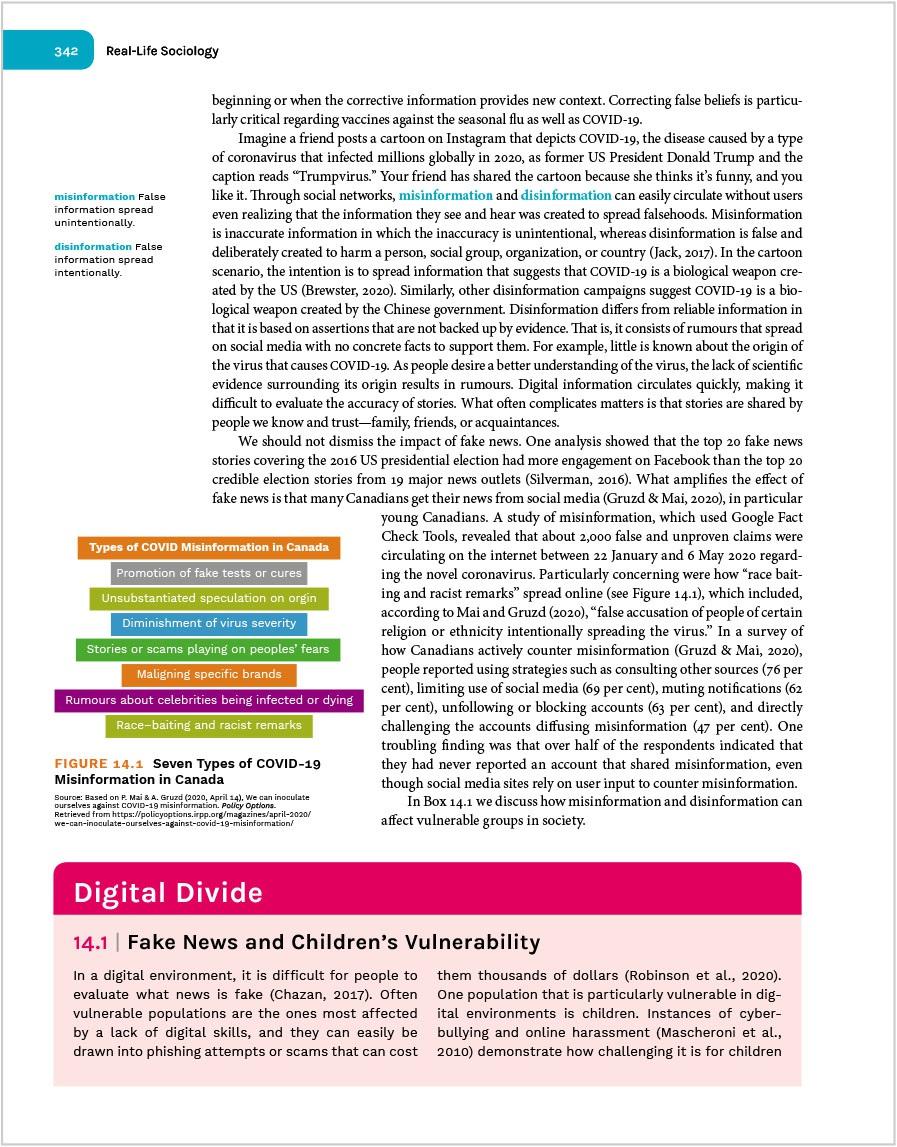

14.1 Fake News and Children’s Vulnerability

15.1 Social Inequality and Pollution

16 2 TheArab Spring of 2011:ATwitter Revolution

Spotlight On

Spotlight On boxes illustrate key sociological concepts with relatable, familiar examples.

1.2 The Social Determinants of Health

2.4 Alice Goffman’s Ethnographic Work in Chicago

3 4 Foodies

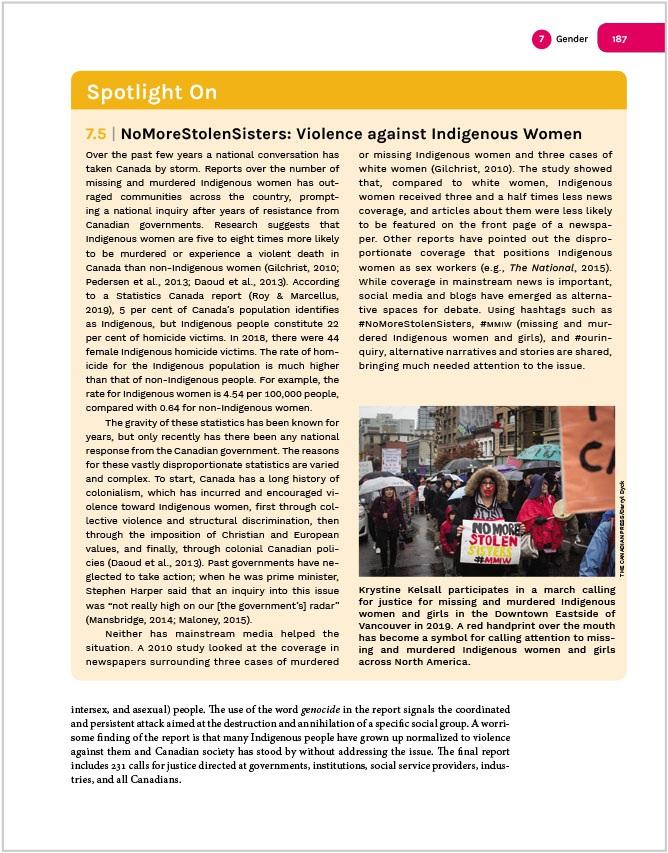

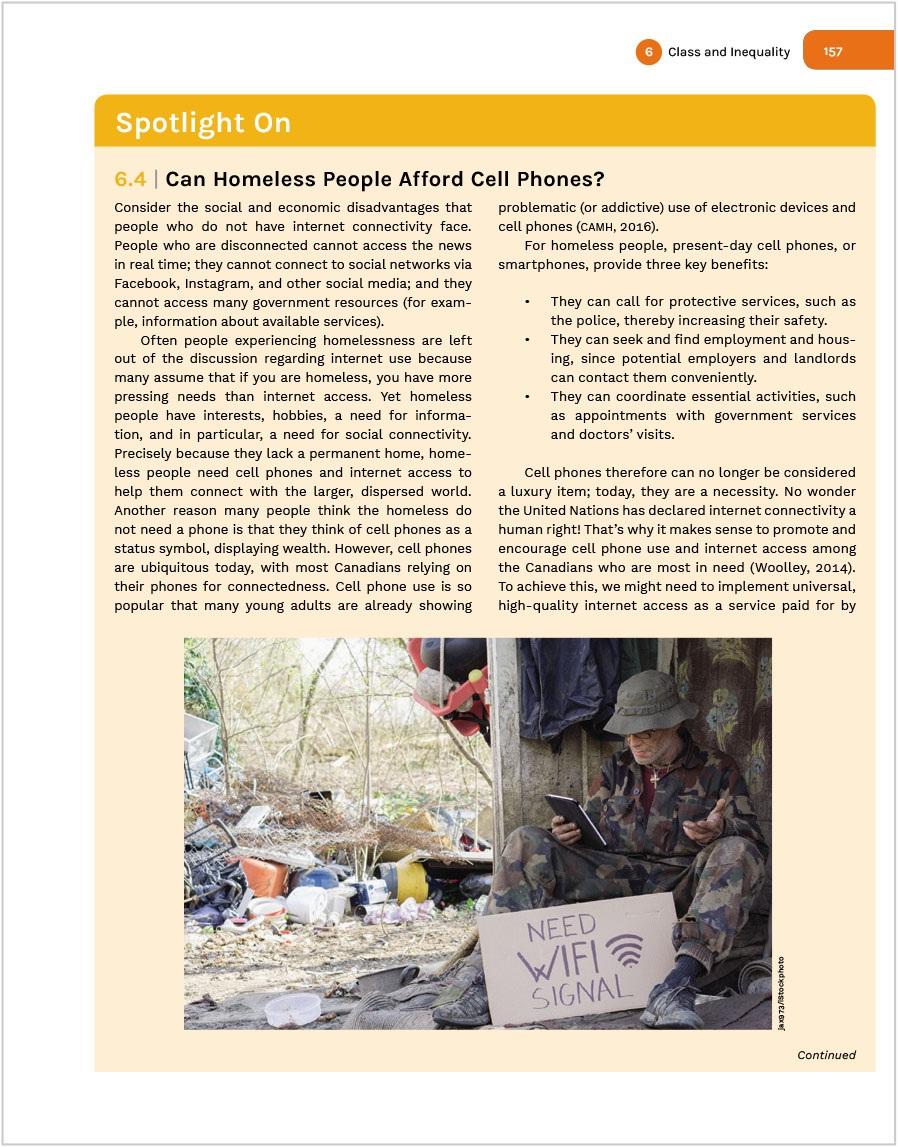

4.1 Appearance Norms Influence Young Girls’ Sense of Self 5 3 Shopping Online and Credit Card Hackers 6 4 Can Homeless PeopleAfford Cell Phones? 7.5 NoMoreStolenSisters: Violence against Indigenous Women 8.3 Indigenous Youth and Suicide 9 3 The Variety ofAdolescent Experiences 11.1 Fundraising and Social Inequality 12.2 Five Famous Women Inventors 13 4 Should Governments Try to Enforce Secularism? 13.5 Lingering Effects of the Potlatch Ban 14.4 Vertical and Horizontal Integration and the Irving Oil Company 15 2 The Development of Renewable/ Sustainable Energy 16.4 Idle No More

Oxford Digital Product Descriptions

The Oxford Digital Difference is the flexibility to teach your course the way that you want to. At Oxford University Press, content comes first. We create high-quality, engaging, and affordable digital material in a variety of formats and deliver it to you in the way that best suits the needs of you, your students, and your institution.

Oxford Learning Cloud

Ideal for instructors who do not use a LMS or prefer an easy-to-use alternative to their school’s designated LMS, Oxford Learning Cloud delivers engaging learning tools within an easy-to-use, mobile-friendly, cloud-based courseware platform. Learning Cloud offers pre-built courses that instructors can use “off the shelf” or customize to fit their needs. A built-in gradebook allows instructors to see quickly and easily how the class and individual students are performing.

Oxford Learning Cloud is available through your OUP sales representative, or visit

OUP Canada’s Sociology Streaming Video Library

Over 20 award-winning feature films and documentaries of various lengths (featurelength, short films, and clips) are available online as streaming video for instructors to either show in the classroom or assign to students to watch at home. An accompanying video guide contains summaries, suggested clips, discussion questions, and related activities so that instructors can easily integrate videos into their course lectures, assignments, and class discussions. Access to this collection is free for instructors who have assigned this book for their course. Accessible through the Oxford Learning Cloud;

speak to your OUP sales representative, or visit www.oupcanada.com/SocVideos.

Oxford Learning Link

Oxford Learning Link is your central hub for a wealth of engaging digital learning tools and resources designed to help you get the most out of your Oxford University Press course materials.

OUP Canada offers these resources free to all instructors using the textbook:

• A comprehensive instructor’s manual provides an extensive set of pedagogical tools and suggestions for every chapter, including a sample syllabus, lecture outlines, chapter summaries, suggested in-class activities, suggested teaching aids, cumulative assignments, and essay questions.

• Classroom-ready PowerPoint slides summarize key points from each chapter and incorporate graphics and tables drawn straight from the text.

• An extensive Test Generator enables instructors to sort, edit, import, and distribute a bank of questions in multiple-choice, true–false, and short-answer formats. Also available is a Student Study Guide for students, which includes chapter overviews

and summaries, lists of learning objectives and key terms, critical thinking questions, recommended readings, and recommended online resources to help you review the textbook and classroom material and to take concepts further.

Talk to your sales representative, or visit www.oup.com/he/QuanHaaseTepperman2e for access to these materials.

Thinking Like a Sociologist

Anabel Quan-Haase

Lorne Tepperman

Learning Objectives

In this chapter, you will:

• Understand the concept of the sociological imagination

1

Simone Golob/Offset com

• Read about the history and development of sociology as a social scientific discipline

• Be introduced to foundational concepts of sociology: social structure, society, social institutions, and roles

• Be able to distinguish between the four main theoretical approaches taken throughout this book: conflict theory, functionalism, symbolic interactionism, and feminism

• Consider how learning about sociology as a discipline can be useful in many aspects of your life

Introduction

Already today, wherever you live and whatever your age, you ’ ve probably done hundreds of things that thousands of other people were doing. Maybe you stopped for coffee on your way to class, or posted on social media about something you watched last night, or put off writing a difficult message to someone. That doesn’t make you boring; it just makes you human.

Humans like to feel like part of a community, and part of being a community member means doing the same things that other community members do. Humans also like to exclude people from their community and compete with people from other communities. Belonging to a community includes pressures to conform and punishment for not conforming. With your behaviour, among other things, you signal to your community of friends that you belong. On a selfie, for example, you might use particular visual cues, slang, references to other media, or commentary such as hashtags or memes to include those “in the know” and exclude potential viewers who are not members of your community.

Have you ever asked yourself why selfies are so popular? Diefenbach and Christoforakos (2017) write that there is a “selfie bias” a tendency to view our own selfies as ironic and only half-committed that allows us to satisfy our desire for self-display without feeling narcissistic (or stuck up). That’s why selfies have been such a success in our social lives: they let us show off without looking like we ’ re showing off. Paradoxically, other research suggests that this practice may backfire: that taking and posting selfies often increases people’s social sensitivity and lowers their self-esteem (Shin et al., 2017).

Two other dynamics also likely drive selfie creation: a desire to innovate and a desire to imitate. In many ways, whatever selfie you may have posted this week looks like a million other posts, so in that sense it is imitative. But, in small ways maybe the expression you ’ re making in a photo, the exact phrasing you used in your description, or the filter you added your post is a tiny bit unusual, even unique. That little bit of weirdness or specialness is your innovation, though it remains innovation within an acceptable range of behaviour. We are always aware of what our friends and

acquaintances are ready to accept. In other words, we innovate to stay included, and only innovate within an acceptable range in order to not be excluded.

These two dynamics inclusion and exclusion are a central part of the story we tell about sociology in this book. We will repeatedly look at how people connect to and communicate with one another in communities and societies: how we teach one another, learn from one another, copy one another, and restrict one another. We will also look at how people cooperate with, compete with, reward, and punish one another. And we will see all these inclusive and exclusive behaviours come to life through interactions between individuals and groups.

In short, as we will see throughout this book, almost everything you think, say, and do is social. However innovative your actions may be, they are also imitative. However hard you may try to separate yourself from one group of people, you are usually also aiming to connect yourself with another group of people.

These processes are hard for people to see at first. We all like to think of ourselves as unique, special, and remarkable. Similarly, most of us are used to thinking about our problems as individual and deeply personal. However, this course will teach you to consider the wider forces at work in your (and everyone ’s) lives. Often, the problems you are facing pressure to do well in school, your growing student debt, or uncertainty about what career to prepare for are widely shared with other students.

When problems that seem individual are widely shared by a similar group, it’s time to think like a sociologist. As you will see, there are large social forces that are shaping your own life and every other human life. In order to see them, you need to activate your sociological imagination.

The Sociological Imagination and Sociology’s Beginnings

Time to reflect

What had you heard about sociology before you started reading this book? Think about your expectations of sociology as a discipline as you read about and are introduced to its key concepts.

C. Wright Mills and the Sociological Imagination

Today, every sociologist understands the importance of sociological imagination. Many decades ago, the American sociologist C. Wright Mills (1959) defined sociological imagination as a “vivid awareness of the relationship between personal experience and the wider society” (p. 5). The sociological imagination is not a theory but an outlook that makes us connect the situations we experience in our lives to broader societal events. It is also a deeply historical undertaking, pushing us to compare our own society to other societies at other times and places. The role of history in shaping present-day society cannot be ignored if we are to be good and imaginative sociologists.

Mills (1959) wrote that the sociological imagination requires us to connect large and small, fast-changing and slow-changing parts of social life. This imagination makes us aware of the relationship between individuals and the wider society in which they live. It pushes us to look at our personal experiences in a more objective way. It urges us to ask how our lives are shaped by the social, cultural, economic, political, and environmental context in which we live. In this way, the sociological imagination helps us think of society as the result of millions of people working out their personal lives. As we do this, we are shaped by society and, reciprocally, we participate in changing it.

For example, it helps us see that, often, our actions are the product of (invisible) norms

and values; such invisible norms and values exist in every society, though they change over time. We generally do what people have told or taught us to do because we want social approval. Our actions take place in a particular social context that makes some choices easy and other choices difficult. Equally, our actions affect other people and in that way they shape the society we live in and contribute to changing society.

Developing a sociological imagination means learning to shift from one way of thinking to another. This often means trying to see the world from a new angle, from outside our culture and outside the socialization we have received. Often, we can do this only by questioning what everyone thinks is true. In short, applying the sociological imagination forces us to break free from personal experiences and assumptions, if only for a while.

Often, this way of understanding leads sociologists to empathize with people who have been disadvantaged by the norms, values, and structures in society and to seek social justice. Mills thought that a lack of sociological imagination could make people apathetic that is, unwilling to study and help disadvantaged people. Without a sociological imagination, people might lose their ability to respond empathetically to human tragedies and injustices or to effectively criticize their political leaders. They might lash out at disadvantaged people or offer individual solutions rather than try to change the system that created the disadvantage in the first place.

In studying sociology, you will find many opportunities to use your sociological imagination. Using your sociological imagination will mean applying critical thinking skills to social issues; however, the sociological imagination is more than critical thinking. It is a way of thinking about society as a tapestry of individual lives interacting and evolving in time. So, though the sociological imagination is challenging, we think it will make the world come alive for you and help you to see your life in new, more interesting, and provocative ways.

Understanding sociology also means seeing the general in particular cases. By this, sociologist Peter Berger (1963) meant looking at seemingly unique individual events or circumstances and finding patterns and trends that might point to broader forces at work.

For example, marriage may be a unique event in a person ’ s life. Nonetheless, sociologists can see it as one of many life transitions or changes a person will make that are remarkably similar to other changes. We can compare marriage to graduation, a first

job, parenthood, divorce, retirement, or widowhood, for example. Like these other transitions, marriage changes how a person spends their time and money, the people they associate with, and the opportunities and barriers they face. It even changes the ways they see themselves and other people, as do other major life transitions.

This generalized view of marriage is simple and understandable. However, you may never have thought about it this way before. According to Berger, sociologists need to hone their imagination by seeing the strange in the familiar. They do this by looking at things that appear ordinary and straightforward, and then rather than taking them for granted, question everything about them. For example, questions as to why someone would choose to get married at all, to whom, at what point in their relationship, and what the marriage ceremony would look like might not even be considered but can reveal a lot about the circumstances in which someone finds themself. Often, travelling abroad helps us see the strange in the familiar and the general in the particular. We will say more about revealing social and cultural differences in Chapter 3.

With the help of both techniques seeing the general in the particular and the strange in the familiar we use our sociological imagination to connect personal troubles to public issues.

Recommended Resources

Already interested in learning more about Sociology as a discipline? Try out an episode of CRStal Radio, a podcast of the Canadian Review of Sociology, to hear about the work Canadian sociologists are doing today.

The Beginnings of Sociology as a Discipline

Most present-day sociologists will tell you that the modern study of sociology began two or three centuries ago. The Age of Enlightenment (roughly 1650 to 1850) was a significant era in European philosophical, intellectual, scientific, and cultural life. The Enlightenment promoted secular (nonreligious) institutions, the rule of law, free economic markets, and mass literacy. Enlightenment thinkers opposed despotic political power, religious superstition, and the traditional hierarchies (monarchy, aristocracy,

and clergy). Enlightenment thinking also admired and promoted science.

Time to reflect

If you read about the history and development of sociology as a social scientific discipline, you’ll find the widely accepted view that sociology emerged from a lengthy debate between tradition and the so-called Enlightenment. Why would the support of science, rationality, and secularism be central to the development of sociology as we have described the field so far?

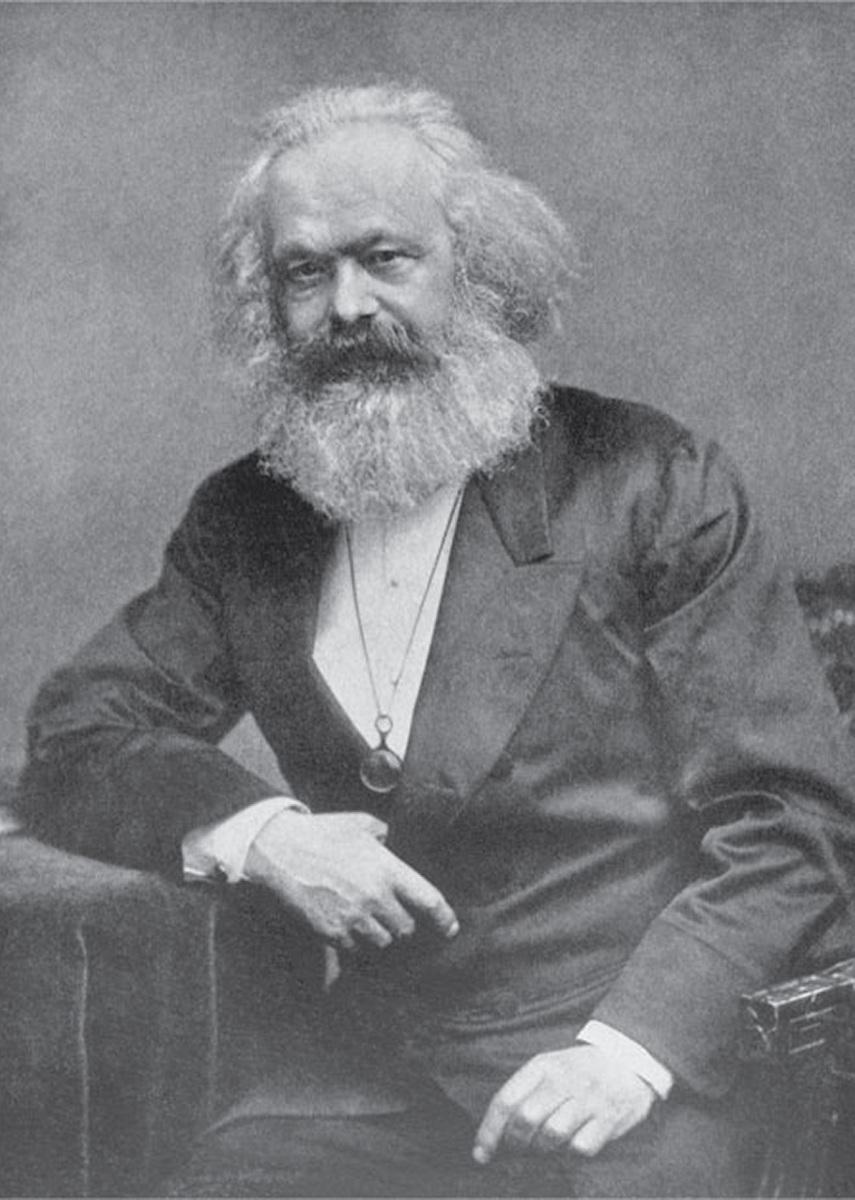

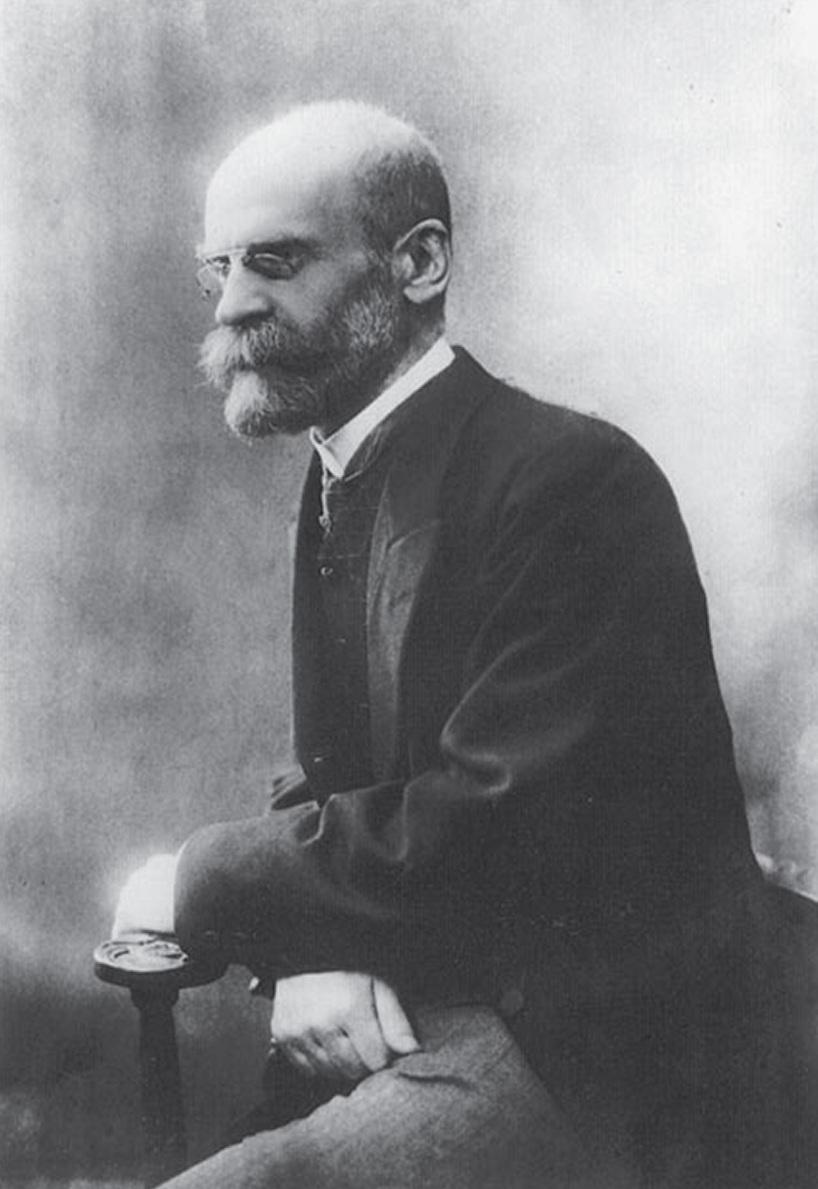

In the early nineteenth century, armed with knowledge of Enlightenment thinking and its effects on traditional social life, sociologists began to develop a science of society. Through evidence-based theories, they thought that people would be able to build better communities in the future. These ambitions are obvious in the writings of sociology’s three founding figures: Émile Durkheim, Karl Marx, and Max Weber (see Box 1.1).

THEORY IN EVERYDAY LIFE

1.1 | Founders of Sociology

Émile Durkheim was born in 1858 in France, a Jew in an anti-Semitic European world. Instead of becoming a rabbi like his father, Durkheim followed an academic career. He completed his doctoral thesis The Division of Labor in Society in 1893 and soon after completed his classic study Suicide in 1897 In many ways, Durkheim wrote Suicide (1897/1951) to set up sociology as a recognized academic discipline. He based his approach in Suicide on what he called the sociological method. It rested on the principle that suicide revealed social patterns that is, variations in incidence according to gender, age, religion, marital status, location, and period, for example. For this reason, sociology must study “social facts … as realities external to the individual.” Durkheim showed that existing, nonsociological explanations of suicide were inadequate. He distrusted explanations of suicide that relied on evidence provided in suicide notes or family accounts of the death

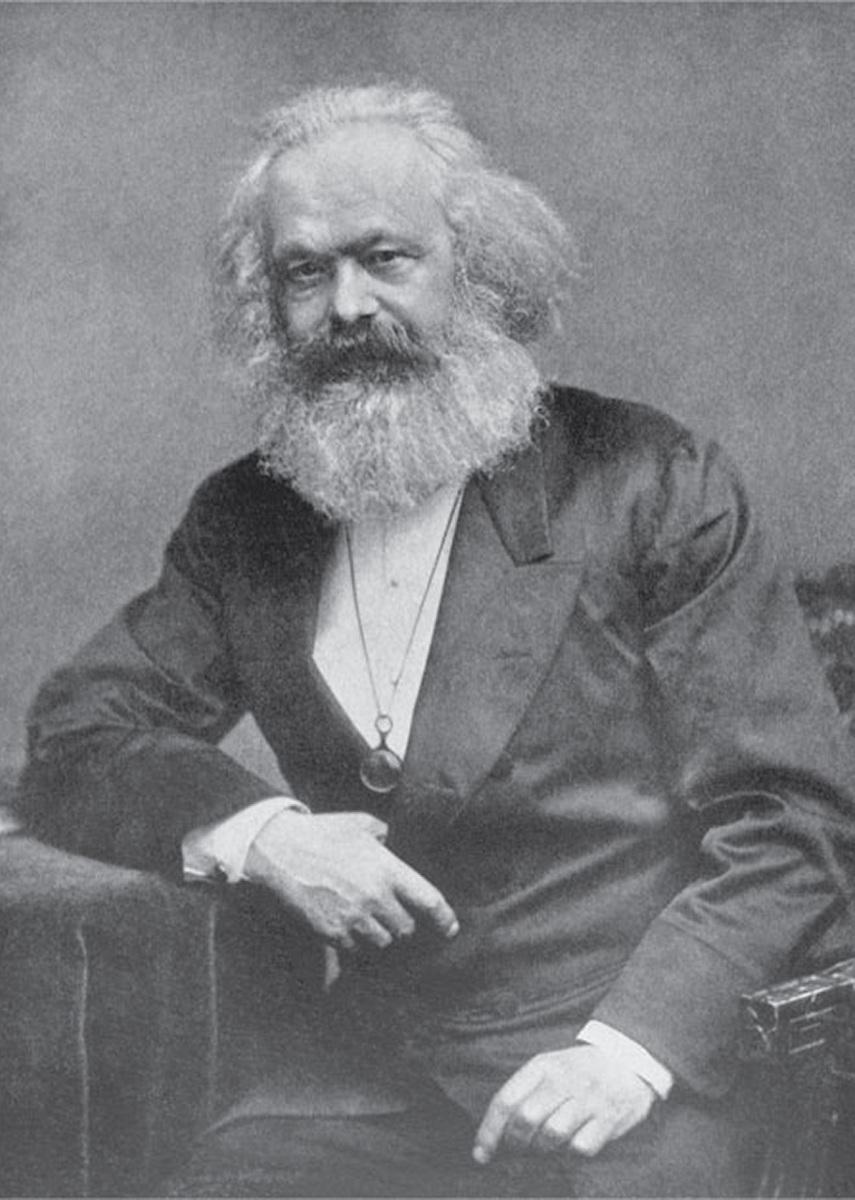

Karl Marx was also born a Jew in Prussia, in 1818. In 1843 he married and moved to Paris, where he met Friedrich Engels. They both joined the Communist League and in 1848 published Manifesto of the Communist Party (also known as

The Communist Manifesto) Soon after, Marx and Engels moved to London for their own safety. Marx’s views continued to win him both admiration and persecution for the rest of his life. In Manifesto of the Communist Party, Marx and Engels proclaimed the unavoidable collapse of capitalism and thus the end to social inequality and social strife. They argued that capitalism continually splits society into two opposing classes, the bourgeoisie (who control the means of production) and the proletariat (who do the work producing goods or services) This antagonism, they predicted, would result in the downfall of capitalism and the end of all class conflict.

Max Weber was born in 1864 in Germany. Weber did his most famous work after 1903 His significant works span various topics: politics, science, religion, law, formal organization, and economics, among others. His most famous book, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, argues that religion was one reason the economies of the West and East developed differently. General Economic History (1923), Weber’s final work, brings together all his unique interpretations of economic change. Weber examined the many ways that social groups gained power in both modern and historical societies. He recognized that people’s relationship to the means of production was only one of many sources of power

Many other early sociologists played essential roles in founding sociology Because of racism and sexism within society and within academia, these important figures continue to be marginalized. Harriet Martineau wrote the treatise Society in America in 1837, in which she criticized the social injustices that women, slaves, and the working poor often experienced. Here and in other work, she stressed the importance of seeing the role of political, religious, and social institutions in promoting inequality. Dorothy Smith, a prominent twentieth-century Canadian sociologist, wrote about one’s place in society affecting how one sees that society (see Chapter 2). Other important Canadian women sociologists have included Grace Anderson, Jean Burnet, Kathleen Herman, Helen McGill Hughes, Thelma McCormack, and Aileen Ross As another significant woman Canadian sociologist, Margrit Eichler (2001) tells us, “All were born before 1930 [and] encountered significant sexism,” yet all found jobs easily. Eichler continues, “Three of the four women whose formative years in sociology were in the 1940s and 1950s did not consider themselves feminists, although all of them did significant work on women.”

Racialized people also played an important role in the development of sociology and continue to do so today. W.E.B. Du Bois did significant work in the

early twentieth century on the effects of slavery and racial discrimination in American society. Frantz Fanon, the great NorthAfrican thinker and psychoanalyst, wrote in the mid-twentieth century about the ways that colonization affects both the colonized and the colonizer Orlando Patterson, a Jamaican-born sociologist, has written prize-winning works about freedom and slavery in the United States and Jamaica. But the earliest racialized sociologist, and the most ignored in the West, was certainly Ibn Khaldun, of the fourteenth century Like Émile Durkheim five centuries later, he studied social cohesion in different kinds of communities and put forward a cyclical theory of nations and empires.

What do you think? As you read this book, see if you can identify the ways that each of these thinkers used their sociological imagination to reveal interesting and surprising social forces.

Space does not permit a thorough discussion of the social and cultural changes that took place between 1650 and 1850 that contributed to the birth of sociology. Let’s say simply that the Enlightenment with its secularism and support for scientific exploration, and its opposition to aristocracy strongly encouraged the rise of industrial technology (known as the Industrial Revolution), the expansion of commerce under capitalism, the spread of scientific and rational thinking, and the growth of democratic republicanism. All of this rapid social change had important social consequences we will discuss throughout this book including the loss of traditional rules, increasing inequality between employers and wage labourers, and new forms of work organization such as bureaucracy.

The principal founders of sociology: from left to right, Weber, Marx, and Durkheim Martineau (far right), an important early influence, is less often read today Keystone Pictures USA/Alamy Stock Photo Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock

Photo © Georgios Kollidas | Dreamstime Chronicle/Alamy Stock Photo

The Enlightenment had led some early thinkers (like the English social theorist Herbert Spencer and French social theorist Henri de Saint-Simon) to imagine a nineteenthcentury leap in social evolution where rational thought triumphed over “nonrational” beliefs. Yet, despite these expectations, nonrational elements of social life such as religious faith persisted alongside the rise of science. Founding European sociologists revealed the social importance of the nonrational beliefs and behaviours (Parsons, 1937). Weber showed that, under some circumstances, religious belief also contributed to orderly change. And while Marx criticized religion for stifling the intellect of the masses and dulling their willingness to rebel, he recognized its political importance. Later Marxists, especially those in the Frankfurt School (discussed later in this chapter), would pay attention to the social and political significance of nonrational beliefs in religion, the media, and culture at large.

Yet we cannot deny the important role of science and technology in sociology’s development. Marx grounded his own scholarship in the transformative power of productive technologies and their effect on class structure. As Weber might say, there was an elective affinity a deep compatibility of goals and purposes between technological change and the rise of sociology. Both technology and sociology sought to improve or better understand the everyday lives of ordinary people through scientific investigation and the systematic application of knowledge. There was also a causal connection between technology and sociology. Sociology, like any art or science, cannot prosper under conditions of poverty and despair. Science and technology, by increasing prosperity and emphasizing structured learning, encouraged the growth of universities and, within them, the growth of academic sociology.

In turn, sociology embraced this new opportunity. Throughout what some have called the golden age of technology (roughly 1870 to 1940), sociology explored ways to solve the social problems associated with industrialization and modernization. In this period, Weber wrote about the rise of science, Durkheim about the rise of modern industrial relations, and Marx about the socially transformative role of technology in work relations.

As you will see, sociology also has deep roots in the humanities, such as social and moral philosophy, and history. It also draws on the writings of people who saw flaws and weaknesses in the Enlightenment project. These authors argued against a wholesale rejection of tradition and saw a place for preindustrial, prescientific, and religious values. They despaired of the loss of community, authority, custom, ritual, and the

personal certainties that went with these social certainties. (For a discussion of these traditional concerns and their role in sociology’s evolution, you might read books by the sociologist Robert Nisbet, such as The Quest for Community [2014] and The Sociological Tradition [1993]).

SelfAssessment

Chapter 1 The Sociological Imagination and Sociology's Beginnings

[Please note: You must be using an online, browser-based eReader in order to view this content ]

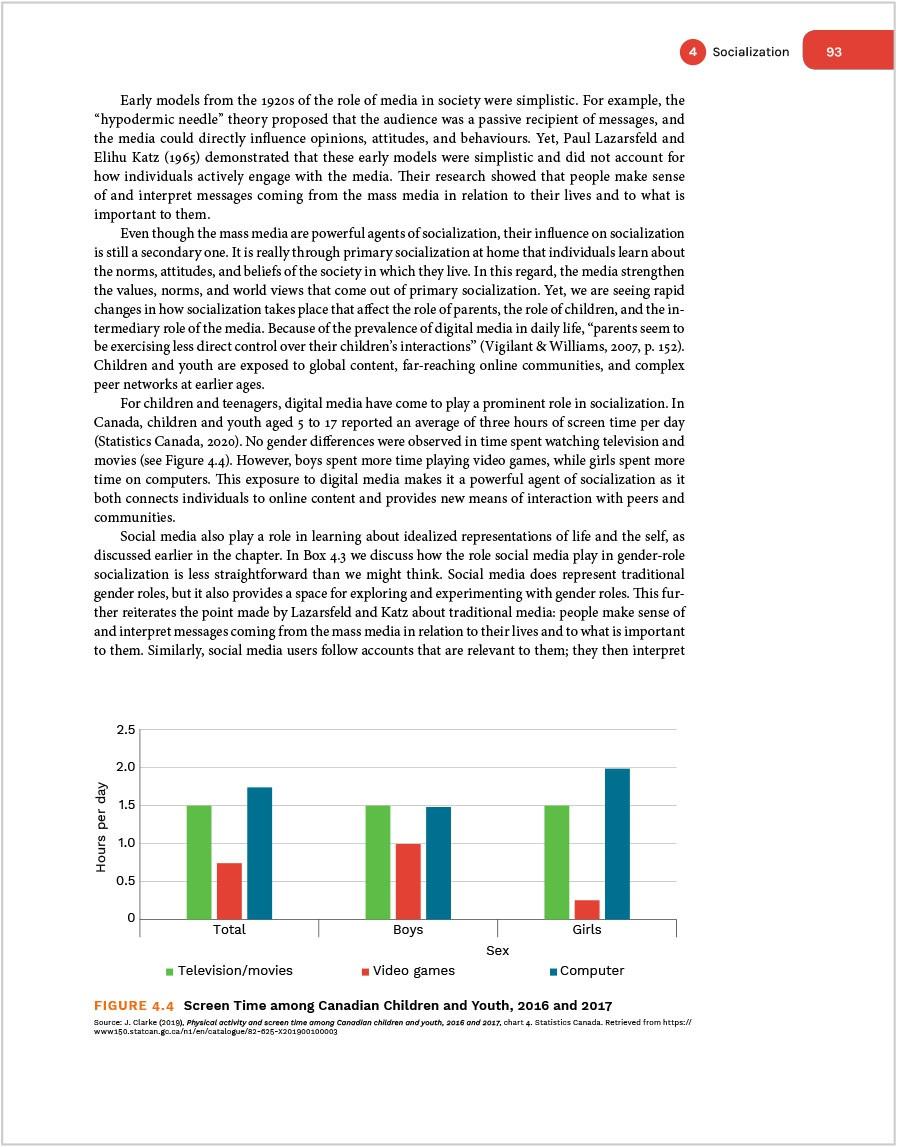

Thinking Like a Sociologist