6 minute read

Respecting Purple

Non-Gender Conforming Narratives & Media Represexntation

By Kally Compton

Billie currently attends Elon University in Elon, NC, and majors in Film & Cinema Arts with a double minor in Philosophy and Gender Studies. “All of my time is spent studying gender in our space,” ey says while reaching for a red can of Cheerwine, then taking a big swig of the North Carolina classic.

Purple is often misunderstood People confuse it with pink or blue They cannot comprehend change The synthesis of something new

Billie shares that eirs gender expression has defined and informed eirs personhood, meaning how ey interacts in a gendered society.

—Anonymous poet in the “non-binary” section of HelloPoetry.com

We sit face to face with a wall of pixels and hundreds of miles between us. This pixel wall is a window into Billie’s world. Billie, whose pronouns are ey/em, wears a dark green sweater. Behind em is a metal rack packed with mostly black jackets. Beatles, Journey, and Billy Idol album covers are fixed diagonally on the wall, and plastic leaves hang from the ceiling.

“My mom wants me to look like Billy Idol,” Billie laughs. “She goes, ‘you should grow your hair out more, to look like that.’”

Billie’s bleached hair blocks the camera as ey looks around.

“My wall space is covered with various shit,” ey admits.

A small plastic pumpkin sits on the corner of the windowsill.

“It’s a light-up pumpkin my dad used to keep out year-round,” Billie says. “My dad gave it to me last year, and I’ve kept it out just to remind me of home.” People try to understand transness as a word you identify as,” Billie shares. “It’s not just a label; it’s much more an experience, a relationship with the social systems around you and the people around you.”

Unfortunately, those social systems have been slow to catch up.

Farrah and I are in the same city, both sitting on our beds and preparing to communicate through our screens. Farrah, whose pronouns are they/them, wears a pink t-shirt and a thick silver chain that cradles their neck. Their brown hair is pulled back in a ponytail revealing their bare face. Farrah says “hello,” then puts on lip balm with their fingers.

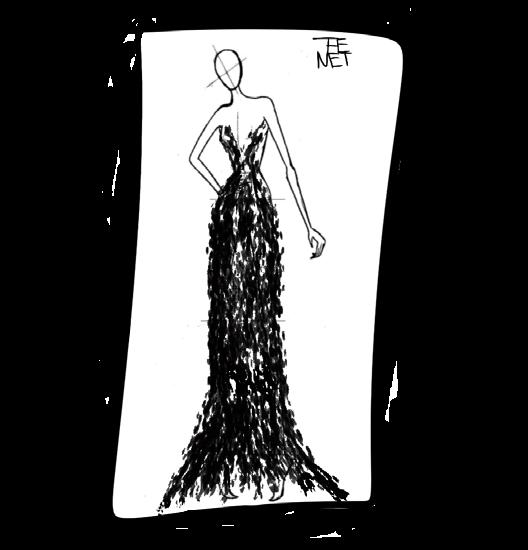

Farrah’s square world consists of dorm walls like Billie’s, but only one wall is decorated. Prints of historic fashion from the MET and ripped out notebook pages with pencil drawings of artistic pencil drawings are taped to the wall. “Everything revolves around gender for me. Whether it’s my art, or my literally everything creative about me, I try to relate it to gender and my fluidity,” they say, twirling their fingers in the air to illustrate.

Fluidity is like water, Farrah says. It is not a solid thing, but flowy and molding into something new. …

The norms of this society are informed and pioneered by media, especially TV and film, and heteronormative aspects of gender and sexuality have always been at the forefront of the mainstream TV networks.

Nevertheless, people who do not conform to societal norms often find liberation within their identity and seek out parts of themselves in the media. Billie and Farrah tend to see only fragments of a mirror when watching films and television.

When Billie was young and considering transitioning, they found inspiration in an unlikely place: the Disney character Moana.

“I wanted to start T so bad that it was physically hurting me. Nausea, anxiety… I was not doing well, but I was terrified of the effects,” Billie says.

“T” refers to testosterone, a part of hormone therapy used when someone transitions. Transitioning is the process of changing the physical features of one’s body to better fit one’s gender identity. Dr. Maddie Deutsch, Medical Director for University of California–San Francisco Transgender Care calls it a “second puberty.”

“I am sitting there watching Moana, and she sings about knowing what she wants. Everyone around her tells her that’s not a good idea, primarily her father,” ey recalls. “They tell her, ‘be comfortable where you are.’ She goes against her father’s wishes, and when she leaves, she is where she needs to be. Later, when Moana talks to Te Fiti, she says, ‘you are not what other people made of you. You are yourself, and you have the right to reclaim your body and your sense of self for yourself.’”

Ey turns around and reaches beyond the screen for something.

“My ex got this for me, but it is the stone from Moana.” Billie holds up an emerald-colored stone to the camera. “So, I carry that with me.”

Farrah, on the other hand, has always thought of themself as Maleficent—not the animated villain in Sleeping Beauty, but the character played thrillingly by Angelina Jolie in 2014.

“You can just see in the first movie, they’re just watching her, and they’re scared of her, and even in the second movie too, they’re like…”—Farrah screams while clutching their chest to imitate the terrified townspeople in Maleficent. “I remember being in middle school, and this is embarrassing, but I would walk through the halls, and people would throw rosary beads at me. And pocket bibles,” Farrah says solemnly. “I’ve always been the antichrist.”

The Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, or GLAAD, creates a report each year to note the representation of trans and non-binary characters on TV. In 2020, it reported, “Across all three platforms [Hulu, Netflix & Amazon Prime], there are 29 regular and recurring transgender characters…15 trans women, 12 trans men, and two trans characters who are non-binary.”

Hundreds of characters from those platforms grace our screens, and yet only two—two—identify as non-binary.

“It’s not that I need somebody to be like me on screen, but it’s also nice to see someone like you on screen,” Billie says.

Representation allows people to feel connected to the world and allows them to accept themselves.

“Will networks allow them to tell their stories or even want them to tell their stories?” Billie asks.

Billie thinks that mainstream media will not be open to the normalization of queerness and non-binariness for a long time.

“A lot of shows have been developed that are very queer, but they aren’t very good.” Ey describes Steven Universe and She-Ra as TV shows directed toward a younger audience, but notes that they lack the production quality and large audiences of most mainstream shows.

In 2018, actress Scarlett Johansson was tapped to play a real-life trans man in a film called Rub & Tug. She received backlash from the transgender community, and after responding with defiance, she ultimately decided to back out of the role. The production was canceled and is being reimagined as a television series that will star a transgender man.

“Imagine getting the offer to play a trans man and accepting the role when you are not. There are trans men without jobs, some homeless even, who could have played the role,” Farrah says.

Farrah knows the horror stories of many non-binary and trans people who are homeless because there isn’t work for them and they have a hard time being accepted socially. They rely on dangerous sex work for money or taking drugs to cope with their mental and emotional troubles. They are nomads without a place in the current social structure.

Billie, Farrah and millions of others would like to see main characters that share experiences similar to the real stories they experience—as opposed to stories designed to be indulged in by “cishet people,” Billie says, using a common term for cisgender heterosexuals.

“Getting cis people to understand us is not the goal,” Billie says. “Getting cis people to just be okay with us existing is the goal.”