4 minute read

David Rigsbee - Carapace

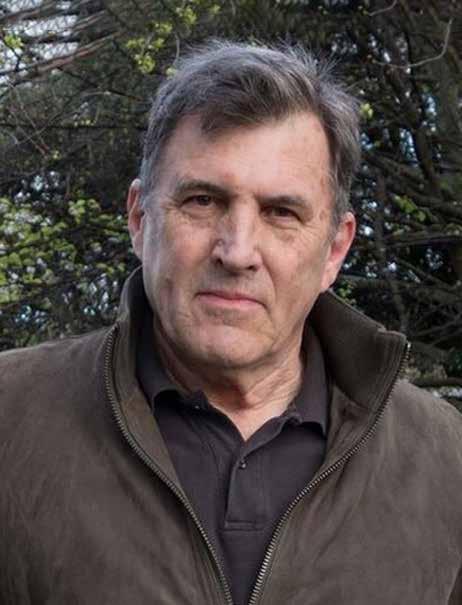

David Rigsbee is an American poet, critic and translator who has an immense body of published work behind him. Not Alone in my Dancing – Essays and Reviews (2016) , This Much I Can Tell You ( 2017), School of the Americas (2012) and The Pilot House (2011), all published by Black Lawrence Press, are but a sample. His complete translation of Dante’s Paradiso is forthcoming from Salmon Poetry.

Carapace

Advertisement

I’m watching a bird drop down from a tree, followed by a leaf. Little masters of trivia, it is late summer. I don’t know what I’m waiting for. The trees are towering, the sky an impasse. Down the hill, the brook makes its way over the rocky debris, forever a signature in its looping. Cicadas start up then tire quickly. I think of myself years ago, of the tiny spot of love I abandoned like the carapace of a cicada. We used to call them locusts, the way they overpowered the pines, helmets of gold, their faces human faces. They saw what the bird did, and the leaf. They saw me then, and then they tired. I don’t know what I’m waiting for. The grass shivers in the small breeze, the grass also small and momentary, all the way down to the water.

Two Shames

I told you I always carried shame that I couldn’t save my brother from the bullet that took him down. You replied it wasn’t my place to rescue such a man, that there was something underneath he was keeping, his own shame, and the fear of it, that parental curse that trailed our childhood and darkened the way. Of course, he had done something, yet it was always there. But why, I asked, did he call me so soon before imploring me to come to dark Ohio, if not to stop him? I turned him down, and that was the shame. You said mine was something I fed on, that let me nibble away over the years. But for him, it was the underlayment of every step he took. You couldn’t have saved him, you said, and I just murmured again: So why did he call me? And why did I not go when I heard the shake in his voice? You looked a long time at me as he would have. He didn’t call you for help, you corrected. He called to say goodbye.

A Greater Poem

Diffuse sunlight in late spring appearing, pulling back along a continuum like stage directions for a play its author hopes to be produced. Instead, a rigid fern leads the eye to a garage it only partially blocks, two locked bays and white swinging doors, then a gambrel loft of blue cedar tiles and at the apex, a window, ten panes in tic-tac-toe with a triangular fanlight all trimmed in white pine. The sill is rotted, though from this distance it could be an outbreak of lichens such as you find on old fence boards. So much rain, and still only the odd daffodil appearing overnight reared-up from the dead grasses. There is a greater poem here, to which access is not granted. Two portly robins glower at me from the brown grass as I walk under the stiff sycamores. After all, who did I think I was going back in memory, even as set out, reverse-striver, rethinking an old poem, thinking this is what I have, and the thought of this poem, as I walked, gripped me tighter, the old poem so quietly unbending.

Second Person

I like the way the wind lifts the glass twine of the green spiders, but I save my praise for the switches to which they are tied, also leaning into the air. I was thinking of switches the other day, how you had to go and select just the right ones when you had been found guilty of something shameful, selection itself being part of the penance and symbol too of how that might be forgotten (it never was) in wake of the lashes, formally laid on to your tiny hide. And nature is both creepier and more absorbing than you thought it would be, coming down to breakfast in your slippers, the little edemas now peeking out from your ankles, like you, bleary to no one in particular. How you hove off into the morning again, switching your point of view into the second person, like a sedan having rounded a curve at the bottom of a hill. Momentarily the glass flashes.

Sunlight connects with the windshield and the oncoming traffic behaves itself. As I say, the cables lift and hold, a fine enmeshment easy to look past, necessary even, in the dappled confusion of ordinary morning, its grim processing of nothing special. The mind says “Let…” and off you go in your fabulous jalopy. Even the weeds may be said to mean you well in their nihilistic way, as you blow past, half in daydream, baseball cap reversed, shading those mythic eyes in back.

Down in His Dreams

Meanwhile, on an emerald swale of moss in the backyard the coyote curls up in full view and sleeps. Dreams perhaps, at least I think so. But my thinking is an imposition, too pat to account for what I’m seeing. He breathes and twitches. It’s enough. I told myself I would never, after the shambolic ’70s, write about a coyote, but that’s the thing, isn’t it? He is down in his dreams. Cassiopeia and the Bear will be here directly, and he’ll lunge up.

Detail on a Jukung, traditional fishing boat, Bali, photograph by Mark Ulyseas.