9 minute read

Hall Showcase Station of the Past

HALL PROFILE:

BY BERNICE HALSBAND, TORONTO FIRE FIGHTER, STATION 232-C

Imagine that the year is 1834. Within the past decade, aluminum has been discovered and aluminum powder is being made in Germany. In the US, the Democratic Party is created. Napoleon has died on Helena, and the fi rst photographs have been developed in France. Typewriters have just become a “thing” in the world.

Toronto has just been incorporated as Ontario’s fi rst city. Its northern city limit is Bloor Street and the streets are mostly packed dirt. The Toronto Islands are still attached to the mainland (and will be for another 20 years) and William Lyon Mackenzie’s party, the Reform Party, has won the elections and chosen him as Mayor of Toronto. You’re walking north on Bear Street (now Bay Street) towards Lot Street (now Queen Street), not towards Old City Hall (that was not completed until 1899), but for a stroll through the woods.

Suddenly the bells ring from St. James’ Church (the only bells in the city), and shouting can be heard. “FIRE!!”

The voices shout out as smoke billows from the east. After what feels like forever, the earth shakes as goose-neck fi re engines, drawn by horses, race past you. First, they head south to the bay to fi ll up an onboard reservoir with water, then to the fi re that has been growing steadily. Citizens have been trying to throw buckets of water on the blaze to no avail. The only chance the building has is the pump that throws a “5/8 or ¾ stream about 140 ft.” (History of the Toronto Fire Department, published 1924).

To your relief, you see not one, but two quickly moving apparatus thundering up the street towards you, with horses foaming at the mouth as they gallop with 32 men hanging on for dear life. There are 16 men on each ‘pump’, one named York and one named Phoenix, with 8 men on either side of the brakes. The earth is shaking as they draw nearer. It is clear that they are racing one another.

In an instant, they are cut off by another company, the Toronto, coming from the west. They disappear in the smoke migrating through the streets, still fi ghting with one another to be fi rst on scene.

As crazy as this sounds, it’s not a far cry from South Command fi re trucks today. The biggest differences being that the streets are now paved, we have motor driven trucks, and the fi rst in truck doesn’t get more money for showing up fi rst. But let’s be honest; who hasn’t had a giddy moment or two beating another truck into a fi re; especially in their fi rst run area?!

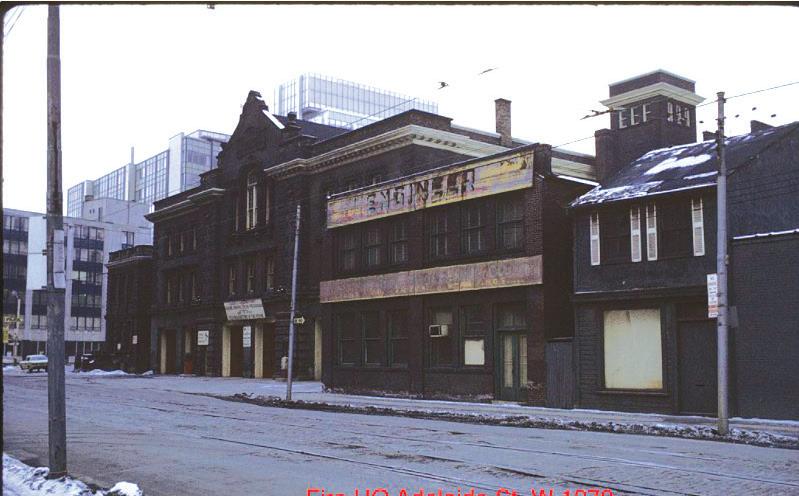

HALL PROFILE: STATIONS OF THE PAST

Toronto is not great at preserving its historic buildings, and fi rehalls have suffered the same fate as other great edifi ces. In many cases, such as “Old 4” at Berkley and Dundas or “Old 9” at Ossington, north of Queen, the building still stands but has been repurposed. Old 4 is a theater company and Old 9 is a methadone clinic. Old 18 on Cowan, south of Queen, is a community centre and Old 5 on Lombard west of Jarvis is now a school of makeup art and design. We watched history steamroll steadily on as Old 30 became our Union Offi ce and is now no longer in our possession.

Old 19 on Perth Street, Old 11 on Rose, south of Bloor, and Old 2 on Portland, were torn down completely. Housing developments replaced these stations. Others, such as Old 14 were razed to make way for Ossington Subway Station. The old Police Station building that stood next to the hall (a popular combination) still exists now as an early childhood education centre.

The history of fi rehalls in Toronto can be quite muddled, and what we know in the present day is dependent on the literature and mementos that has survived and been carefully protected.

There is no tome that carries all of the defi nitive locations, years built, years decommissioned, and years demolished. Research involves hours of poring over old Fire Insurance Maps to confi rm the exact locations of fabled stations. In short, the history of our department is scattered across the city.

The City of Toronto Archives, at Dupont and Spadina, and the Toronto Public Library Reference Library, at Yonge and Bloor, have an amazing collection that you can peruse. Much of it is available online, but nothing compares to holding the documents in the palm of your hand like an invitation to the Fireman’s Ball in 1855. Policemen, unfortunately, did not have Balls.

The librarians will bring out any paraphernalia you ask for and the history buff in me gets goosebumps knowing that I’m holding the same piece of paper that a Fireman once received over a hundred years ago.

Unfortunately, Fire Insurance Maps are copyrighted, and the newest ones available date back to 1924. Since they are the most reliable way of seeing exactly where the stations stood, it’s hard to fi nd information on when that particular station was torn down past 1924. A lot more digging is necessary. Coincidentally, the ‘History of the Toronto Fire Department’ was published in 1924 and lists the 30 stations that serviced Toronto.

There are old pictures of fi re stations that contravene the literature or are not mentioned at all. Piecing it together requires several different sources. For example: one photograph shows what is clearly Old 22 station on Main Street, with a Police Station in the midst of being built next to it, and what looks like a temporary fi rehall also next to it. That ‘temporary fi rehall’, which presumably housed fi refi ghters while Old 22 was being built, says ‘Firehall No. 2’. At the time that the book was published, that area had only just been incorporated into the City of Toronto, but was still considered ‘East Toronto’.

The need for fi re protection in the east end of the city grew out of the completion of the Prince Edward Viaduct (completed 1918), which opened the entire area east of the Don River for settlement and business. At that same time, the offi cial Station 2 was located on Portland Street, south of Queen in the west end of the city.

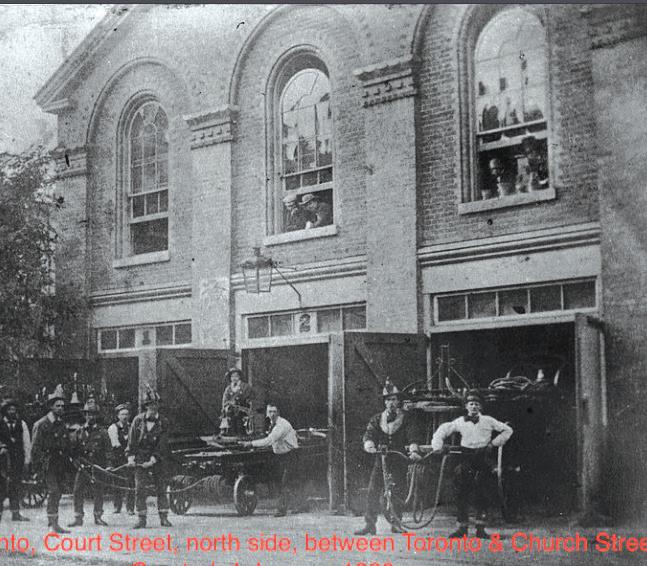

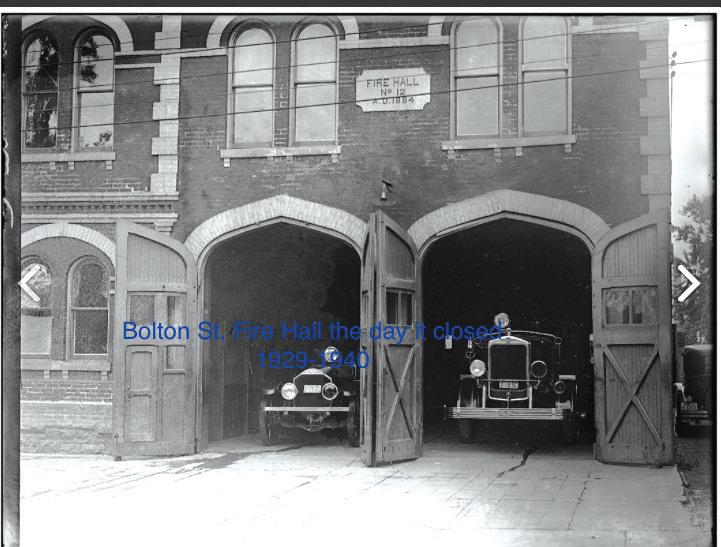

By 1826, the fi rst Volunteer Fire Department was created and housed in a ‘two storey brick building on the west side of Church Street between Court and Adelaide streets’. If it was still there in 1856, it is not marked on Boulton’s Map of Toronto, which curiously shows an ‘Engine House’ on Court Street, just to the west. The Fire Insurance Map from 1880 shows a Police Station and an Engine House. The map from 1884 shows a Police Station and Fire Hall, and the 1890 map, just a Police Station.

Of the 30 stations listed in ‘The History of the Toronto Fire Department’ from 1924, only 10 remain in service today for their original duty. Curiously, No. 8 Station and No. 29 Station are both listed as being at the southwest corner of College and Bellevue Ave. The remaining 20 stations are divided into two categories: 6 repurposed and 14 torn down.

The City of Toronto was incorporated as a City in 1834, roughly 40 years after the fi rst land purchase negotiations with the Mississauga and Huron tribes. I use the word ‘negotiation’ loosely. The treaties are still in hot dispute in the courts today and are constantly being reviewed and challenged, resulting in huge sums of money being paid out to the tribes that once inhabited the city.

The year 1834 also marked the year that Great Britain offi cially abolished slavery in its colonies, arguably replacing and overlapping the abolishment with indentured servitude, which tied thousands of poor immigrants, men, women and children alike, to service for years before they could earn their freedom. To his credit, John Greaves Simcoe attempted the abolishment of slavery in Canada as early as 1793. In 1839, Firehouse No. 1 was built at the south-east corner of Bay and Temperance. St. Patrick Market, a building still standing on the north side of Queen, west of University, housed another company, the Victoria Company. It was organized in 1842 for ‘quite a few years’ until that company moved onto the south side of Queen Street, ‘75ft. from the corner of John Street’. I suspect that this company became Firehose No. 6, but maps confi rm the location of that particular station closer than 75ft. to John St. Maps of Toronto from 1855, show giant swaths of land, consisting of groves and woods that are now dotted with high-rises and commercial endeavors. The census of Toronto shows a population of 1,710 in 1826, 9,254 by 1834 and just over 30,000 by 1851. In contrast, the maps from the 1880s show hundreds of dwellings replacing the undeveloped forests of the 1850s.

Ontario’s population grew by a million people from the 1850s to 1880s due to the huge waves of immigrants. This warranted fi re protection for the thousands of residences and industrial complexes and factories that supported the menial jobs that most people worked. You could argue that the slums that sprang up all over the city needed fi re protection too, but as with today, money talks. I have my personal doubts about the priority they took in the insurance company’s books.

In addition to the waves of immigration from Europe, the second Refugee Slave Law passed in the United States. This made Canada an ideal refuge for freedom-seeking slaves from the south that were trying to escape across the border, risking everything to make a new start in the “Queen’s Dominion”. In 1837, Joseph Taper, a former denizen (not citizen) of Virginia, wrote to one of his friends in Virginia:

“Since I have been in the Queen’s dominions I have been well contented, Yes well contented for sure, man is as God intended he should be. That is, all are born free and equal. This is a wholesome law, not like the southern laws which puts man made in the image of God on level with brutes…I have enjoyed more pleasure with one month here than in all my life in the land of bondage.” 1,500 words do not even scratch the surface of the history of the Toronto Fire Department. I encourage those of you who are curious, to visit the digital archives of the TPL and City of Toronto Archives for pictures and articles related to our history. It is even better for you to visit the actual buildings! A copy of ‘The History of the Toronto Fire Department’ is also available as a digital book. It is a fascinating read and gives the reader a primary source and a contemporary look into the ‘Old School’.