20 minute read

Pelican Sports

After the final buzzer, the boys varsity basketball team and coaches celebrate their Class A New England Championship.

VARSITY RECORDS

BOYS BASKETBALL 20-6

New England Class A Champion Founders League Champion

GIRLS BASKETBALL 16-11

New England Class A Semifinalist

CO-ED EQUESTRIAN 3 shows

BOYS ICE HOCKEY 16-7-4

New England Large-School Champion

GIRLS ICE HOCKEY 19-7-1

New England Elite Eight Semifinalist

CO-ED SKIING

New England Class B, 13th Place (boys), 9th Place (girls)

BOYS SQUASH 6-14

GIRLS SQUASH 5-13

New England Class D, 2nd Place

BOYS SWIMMING & DIVING 9-2

Founders League Champion New England Division I, 4th Place

GIRLS SWIMMING & DIVING 7-3

Founders League, 3rd Place New England Division I, 5th Place

WRESTLING 15-5

New England Class A, 5th Place New England Championship, 18th Place

1 Senior Sky Hanley

2 Sophomore Nick Guenther

3 Sophomore Sophia Testa

6 Freshman Brandon Kim

7 Senior Mathieu Schneider

8 Freshman Daisy Xu

2

4

5

7

9

Springtime on Founders Circle. Photo: Jessica Ravenelle

Share a meaningful life experience, in 600 words or fewer.

Photo: Lynn Petrillo

This essay by junior Haven Low was selected as a runner-up in a New York Times personal narrative essay contest for teenagers, which drew 8,000 entries from around the world. Haven’s essay was one of eight runners-up in the contest, which prompted entrants to write about a meaningful life experience in no more than 600 words. Basing their criteria on the kinds of powerful personal narratives that appear regularly in the New York Times columns “Modern Love,” “Lives,” and “Rites of Passage,” the contest judges chose 35 finalists, from which they selected eight winners, eight runners-up, and 19 honorable mentions.

by junior Haven Low

The dewy grass and decomposing concrete crunch under my feet as I trudge to the first morning of my job as a camp counselor. I sport an official t-shirt, an unflattering, eye-catching garment, reluctantly thrown atop of a bathing suit. All I want to do is hide. I am extremely self-conscious about my physical shape. At 16, I have grown out of my girlhood but not yet into my womanhood. I exist somewhere in between? I feel like an imposter in this brightly colored cloak of responsibility. It takes all of my will to stop from turning around and retreating to the comfort of my bedroom.

Suddenly, I think of the campers set to arrive for their first day together, all of whom identify as transgender or gender non-conforming. If I am this uncomfortable in my gender-conforming body, how must they feel? Surely these second graders won’t care how I look in a bathing suit, I think. This realization gives me courage and a renewed sense of purpose. In the midst of their own struggles to reconcile gender with anatomy, they won’t think to judge my appearance. Or will they notice my own insecurities?

As I turn the corner, with clammy hands and a knot in my stomach, the director greets me with a warm smile that calms my fears and leaves me mostly forgetful of my earlier doubts. In the final moments before campers arrive, we promptly cover the driveway with colorful chalk streaks and the words “Welcome to camp!” I chew my nails as I wait for the chaos to begin. Despite the nerves churning in my stomach, the world seems so peaceful and the birds chirp through the early morning wind. Will these kids accept me? Will they like me? Again the concrete crumbles as cheerful parents in minivans pull up, smudging our colorful chalk designs. One by one, I observe and greet each camper. Each child brings a story, an identity, of their own. There is the gentle boy who feels most comfortable in skirts striped with pinks and purples. There is the rowdy boy, born female, who runs circles throughout the crowd. There are the identical twins standing shyly together — identical, yet one is a boy and one is a girl. They keep coming.

I suddenly understand I have the responsibility of creating an environment where the kids all feel accepted and comfortable. They walk a complicated path and deserve all of the love and support I can give them. Placing my preconceptions and self-doubt in my backpack, I approach a shy kid with a rock-and-roll haircut and rainbow leggings. I have absolutely no idea how they identify. Luckily, their suburban mom with frizzy curls and a cup of pungent coffee in hand reads my mind and answers my question.

“This is Quinn,” she says. “They are gender non-conforming.”

I am barely prepared for this. They are a singular person, I think, knowing it will take effort to remember the correct pronoun. Quinn looks me in the eye, and an impish grin spreads across their face. I smile in return. I am astonished that at the age of seven, Quinn understands their identity and is not afraid to show it to the world. They, without a doubt, embody self-acceptance, despite living in a world where far too many people equate them with being foreign and freakish. I realize how much I can learn from these kids as I walk my own path of self-discovery. Taking a breath, I settle into myself and my excitement. Without hesitation, Quinn grabs my hand and drags me towards a week full of self-exploration, expansion, and discovery.

GRAPHIC NOVEL

by CHRISTINE COYLE

Alumni may be familiar with MAD Magazine’s biting satirical comics, which included the double-crossing antics of “Spy vs. Spy,” whose wordless, black-and-white panels were meant to be a sendup of Cold War espionage. And some, perhaps, took pleasure in the subversive nature of reading comics because wise and learned adults discouraged young people from “wasting time” on them and their ilk in favor of respected works of literature and the classics.

Over time, comics came of age, and writers and artists embraced this evolved literary form as graphic novels, with a unique and expanded storytelling ability through the use of visuals, as compared to text alone. The oeuvre has grown quickly and has entered into the cultural and academic mainstream — including as an English elective at Loomis Chaffee.

Team-taught by Timothy Lawrence and Will Eggers for the last five years, the 10-week term course English IV: Graphic Novel examines the history and structural composition of comics, their evolution into the literary art form known as the graphic novel, and the cultural significance of the graphic novel.

So, what’s the difference between comics and graphic novels? And why study the graphic novel as a literary exercise?

There is a fine line between the two, according to Tim and Will, just as a fine line exists between “literary” fiction, like Shakespeare, and popular fiction.

The term “graphic novel” is often associated with serialized comic books, but in this class the graphic novel texts are complete, original stories, not segments of a longer story as one might find in a comic. Tim and Will explain that graphic novels use sequential art panels to frame story segments and employ audio, gestural, spatial, or linguistic modes to help tell the story. The stories they portray unfold across a specific period of time and space. Beyond comic books, graphic Will Eggers and Timothy Lawrence teamteach the Graphic Novel course. Photo: Jessica Ravenelle

novels provide more sustained, deeper exploration of character and themes across a range of complex emotional and philosophical topics. The genre presents many rich opportunities for interdisciplinary and multicultural analyses with the added element of a visual “voice” to convey meaning.

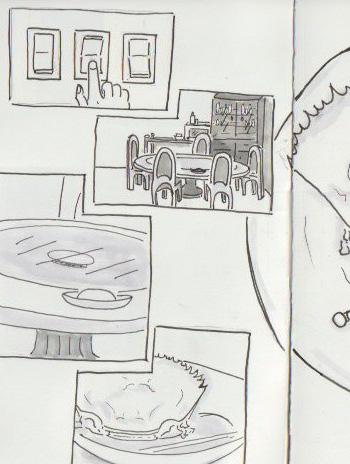

Students in the class examine graphic narratives of fiction and nonfiction and learn interpretive methods and a “visual vocabulary” from which they may draw their analyses. Throughout the term, students progressively build their visual storytelling skills through drawing exercises in sketchbooks and in-class exercises on whiteboards. For a final project, each student conceives, develops, writes, and illustrates an eight-panel graphic short story using some of the narrative techniques covered in class.

Graphic Novel is an English Department course, not a Visual Arts class, and students are not required to have any experience in art or drawing to take the course. In fact, Tim notes, some of the most exceptional student final projects employ only rudimentary drawings for visuals. “The ideas are more important than the actual drawings,” he explains.

At the beginning of the term, students read and discuss Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, by Scott McCloud, which provides a “tool kit” for students to look at some of the meaningful graphic communication found in the novels, according to Tim and Will.

“We’re calling an audible today,” Will says before the start of a Monday morning class — the day after the NFL Superbowl — as he and Tim draw figures on the whiteboards around the room. That day’s class discussion focuses on Asterios Polyp, a graphic novel by David Mazzuchelli. The novel’s main character, Asterios, is a university professor and professional architect of Mediterranean descent who is in the midst of a divorce and who struggles with mid-life regret. According to Tim, Mr. Mazzuchelli uses Greek mythology, concepts of philosophy, and elements of architectural design in his illustrations to develop character and add deeper meaning to the story. The figures the teachers draw on the white boards at the beginning of class represent common mythological and philosophical characters and ideas, and correlate with those in Asterios Polyp. They serve as “lenses” for interpreting the novel, and as cues for class discussion, Tim says.

The discussion around the Harkness table looks to an outside observer like any other English literature analysis — except that instead of just reading passages of text to support their opinions and insights, individuals in the group discussion share their thoughts about deeper meanings that are expressed both visually and in text on the novel’s

In a frame from senior Cheri Chen’s end-of-term project, Cheri and her mother converse via text message.

pages. As the students discover, graphic novels convey meaning through artwork within and outside the art panels; in the positioning and spacing of panels; in design elements such as the line, texture, and color of illustrations; in the white or negative space on the pages; and even in the font used to print text.

During an animated discussion of Asterios Polyp, senior Clarke Thrasher points to the solid blue lines and perfectly formed shapes in the panels depicting Asterios, who is an architect with steadfast opinions. By contrast, panels containing the character Hana, Asterios’s wife, are made with crisscrossed red lines to form her less well-defined, softer shape, and represent her more malleable opinions. Tim and Will join in the classroom interaction, encouraging the students in their thought processes, interjecting their own opinions, throwing out questions for the group to consider, and engaging in spirited academic debate with each other.

Everyone seated around the table takes the opportunity to closely examine the book’s pages and consider each other’s interpretations in uncovering possible clues to the novel’s meaning.

“It is a re-telling of the story of Orpheus from Greek mythology,”

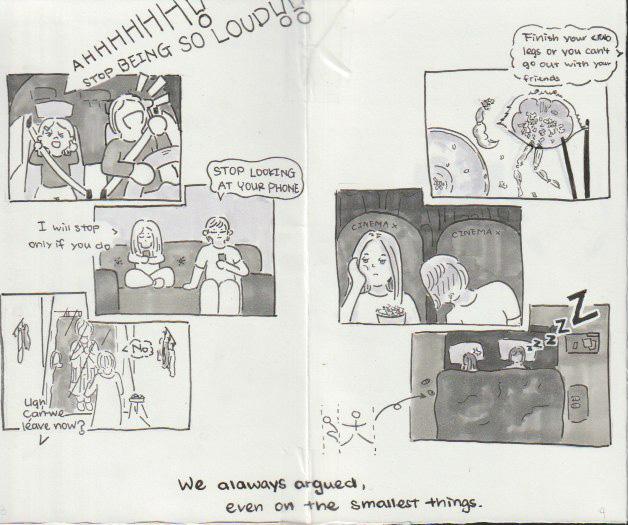

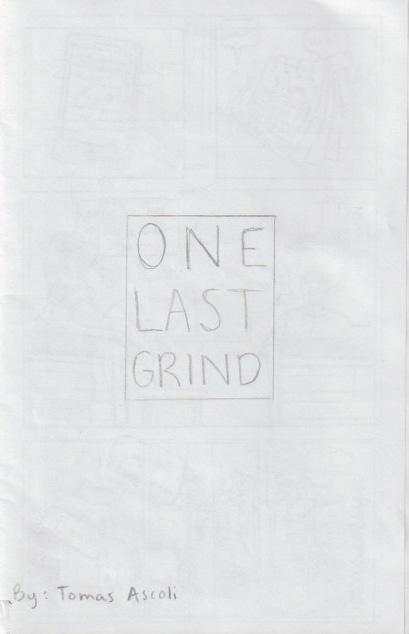

TOP & BOTTOM Pages from senior Tomas Ascoli’s graphic short story, which takes a self-deprecating look at his college process.

Tim affirms as the group teases out this conclusion. Tim and Will describe Asterios Polyp as the graphic novel equivalent to James Joyce’s Ulysses.

Both instructors share an affinity for the genre, and they enjoy seeing their students come to appreciate the novels. In addition, Tim and Will say they love the rare opportunity for professional collaboration in the classroom. Collaboration benefits the teachers professionally, Tim says, but also helps students by modeling intellectual discourse and idea sharing, especially when the teachers don’t agree with each other.

“We really encourage the students to reach, stretch, be playful, and to be wrong sometimes,” Will says. Teaching the class with Tim for the past five years “has been a wonderful experience personally and professionally,” he adds.

In addition to Understanding Comics, and Asterios Polyp, the class studies Maus, by Art Spiegelman; The Arrival, by Shaun Tan; and Fun Home: A Tragicomic, by Alison Bechdel. The students read Maus, a biographical story of a Polish Jew living through the Holocaust, published in book form in 1986, because it helped establish the credibility of the graphic novel in literature by showing what the form had to offer in covering serious topics. The Arrival uses the graphic form to eloquently express the immigrant experience without any narration or dialogue — a moving effect that simulates being unable to communicate in a foreign land. And Fun Home mixes literary references, provides readers with a window into what it’s like to come of age as a person who identities as LGBTQ+, and offers insights into the author’s nuanced relationship with her father.

The unconventional genre of the graphic novel warrants some unconventional lesson plans. In one such lesson, as the class studies The Arrival, which has no text at all, students show up at Chaffee 102 and are informed that they must communicate without any words in class that day. The students draw pictures, follow visual cues, and collaborate with classmates to decipher the assignment. They come to appreciate how to communicate wordlessly, Tim says.

In other lessons, every student takes a turn at “owning” a novel — being the discussion leader for one of the all-class reads during the term. Each student must prepare for the lesson as a teacher would, with thoughts and ideas ready to introduce to spur dialogue, Tim explains. In the classroom, both teachers have collected a library of graphic novels to supplement those available to students in Katharine Brush Library. In an exercise Tim and Will call “Grab Bag,” each student chooses a graphic novel from the classroom collection, reads it, and then gives a five-minute description to the rest of the class.

A two-page spread of Cheri’s graphic short story, which tells a touching, nuanced story about her relationship with her mother.

The course has grown in popularity since it was introduced in 2015–16, and class alumni help spread the word of their positive experiences.

“I came to class with absolutely no knowledge about graphic novels. I chose it primarily because I love art,” comments senior Cheri Chen, who took the class this fall. “I really enjoyed the books. All the small details — the color usage, the shadow and light contrast — I felt like I was putting together a puzzle when I read a book. I still read Asterios Polyp from time to time, and I often find something new and interesting when I read it again.”

Cheri wrote her final project about her relationship with her mother and their differences in opinion and values. In her panels she symbolizes one’s love for a mother as a “legless crab” that becomes hidden deep in the day-to-day of living, but still endures.

Senior Tomas Ascoli, who also took the course in the fall, had previously read some graphic novels for fun, and he admits that he thought the class would require less writing than a typical English course. That was not entirely the case, he says. There were plenty of assignments that required “writing,” many of which included drawing to help tell the story. Tomas says he especially enjoyed reading Asterios Polyp.

Hee Won “Ashley” Chung ’19 took the Graphic Novel course in her senior year and now studies computer science at Brown University. A talented artist, Ashley has been a fan of comics since she was a child and drew her own comics as a hobby. The class gave her the tools to become a better artist, she says, and she enjoyed the structure of the course.

“We had to keep a sketchbook, and we were allowed to doodle in class, as well as being encouraged to fearlessly put down our ideas. Doing homework for this class did not feel like ‘schoolwork,’ necessarily, but it felt like a continuation of my artistic endeavors and hobbies. Overall, I really enjoyed this course, and I think it really helped me grow as an artist,” Ashley reflects.

Reading Understanding Comics as a senior in high school introduced Ashley to concepts that gave her an edge in coursework for a global anime class she took at Brown, she said. This spring Ashley is taking courses in visual arts and Japanese literature in addition to her computer science classes. She also uses her design skills working at the Brown Daily Herald newspaper and at one of the university’s arts and culture publications.

Through the Graphic Novel class, excitement about this literary genre is reaching the next generation of readers at Loomis. Like explorers following a map to buried treasure, Tim and Will are passionate in their quest to unearth meaningful clues woven into the panels of graphic novels, and their enthusiasm is contagious.

The title page of Tomas’s project

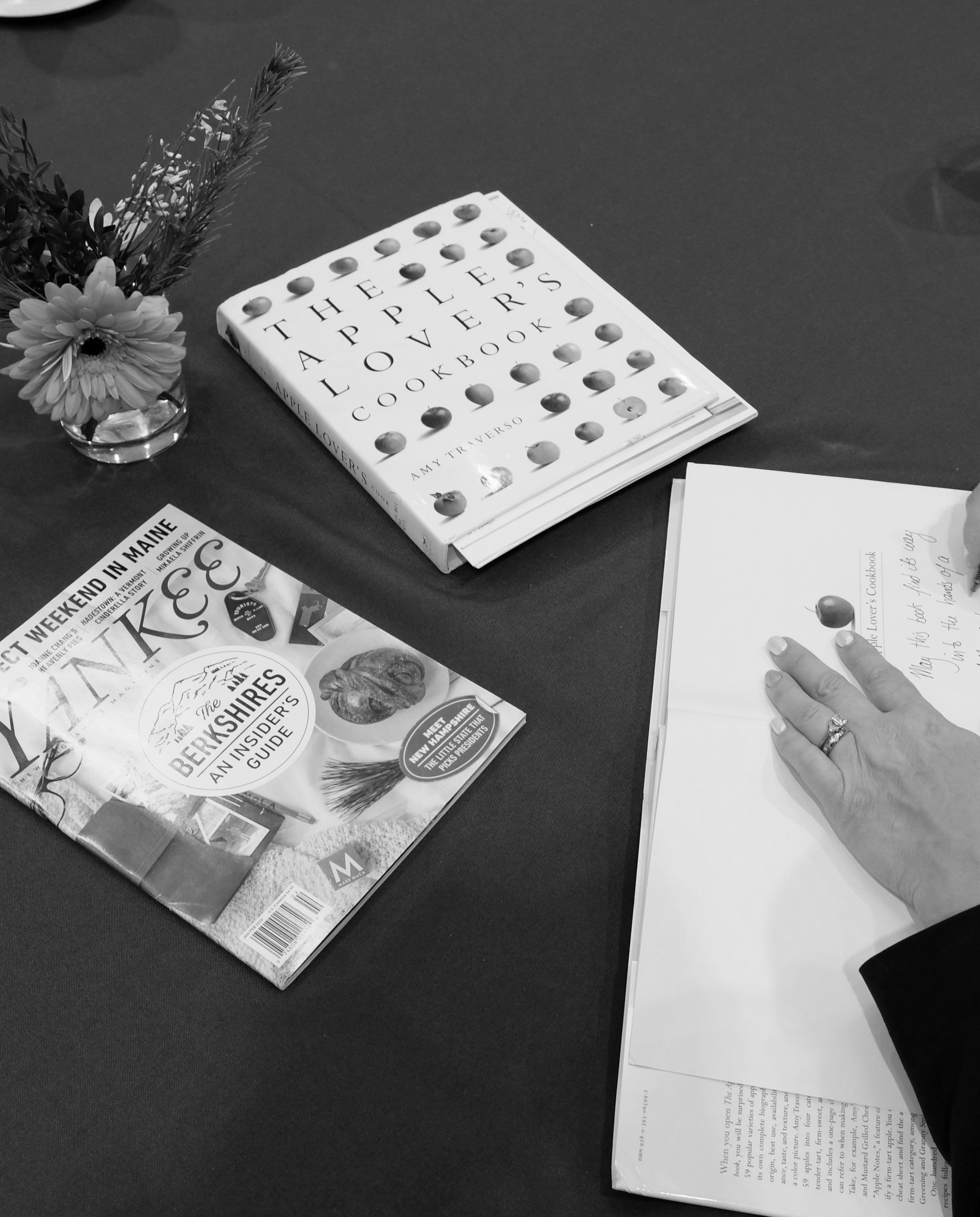

ALUMNI AUTHOR Amy Traverso

Story and Photos by CHRISTINE COYLE

Amy Traverso ’89, cookbook author and senior food editor at Yankee Magazine, returned to the Island in January to share her professional writing experiences with students at a “Dinner and a Draft” event organized by Loomis Chaffee Writing Initiatives.

Amy shared a meal with a dozen student writing enthusiasts — many of whom are involved in student publications and other on-campus writing initiatives — and several faculty members, including Jessica Hsieh ’09, English teacher and faculty advisor to The Log; Karen Parsons, history teacher and Loomis Chaffee archivist; and Kate Saxton, English teacher and director of Writing Initiatives. After dinner, Amy led the group in a writing exercise.

“I didn’t think of myself as a writer when I was at Loomis,” Amy told the students, but she said that writing across the curriculum at Loomis established a strong basis for her advanced study and professional writing career.

Amy realized that writing was one of her strengths when she was in college and helped her college professors with research papers. She took the advice of a publishing professional to enroll in Columbia University’s respected summer publishing course. After landing an editorial assistant job at Boston Magazine, she seized the opportunity to shadow the publication’s restaurant critic and discovered a passion for food writing.

To support themselves financially, food writers should

be able to cook, write for print and the web, style food, and appear at ease on camera, Amy told the students. An entrepreneurial bent and an established social media presence also are important, she said.

“And you need to learn how to write a ‘blurb,’” Amy added, introducing the group’s writing exercise for the evening. A blurb is a short, descriptive paragraph used to describe or critique food. The challenge in writing a blurb, she said, is to “come up with new and fresh ways to describe your senses.”

Amy passed around samples of locally-sourced cheese and biscuits — a common subject for her writing at Yankee Magazine — and asked the students to taste a sample then write blurbs.

In addition to her editorial role at Yankee Magazine, Amy is the author of The Apple Lover’s Cookbook, published in 2011, which was a finalist for the Julia Child Award for best first-time author. Amy also co-hosts “Weekends with Yankee,” which airs on public television stations nationwide. She has served as food editor at Boston Magazine and associate food editor at Sunset Magazine, and her work has been published in The Boston Globe, Salon.com, and Travel & Leisure magazine. She has appeared on The Martha Stewart Show, Throwdown with Bobby Flay, Gordon Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares, and other television shows. Amy lives in the Boston area and returns often to Windsor to visit her family.

For a link to a Hartford Courant story about Amy’s visit to Loomis Chaffee, to view a gallery of photos from her visit, and to find out more about Amy’s work with Yankee Magazine, visit www.loomischaffee.org/magazine.

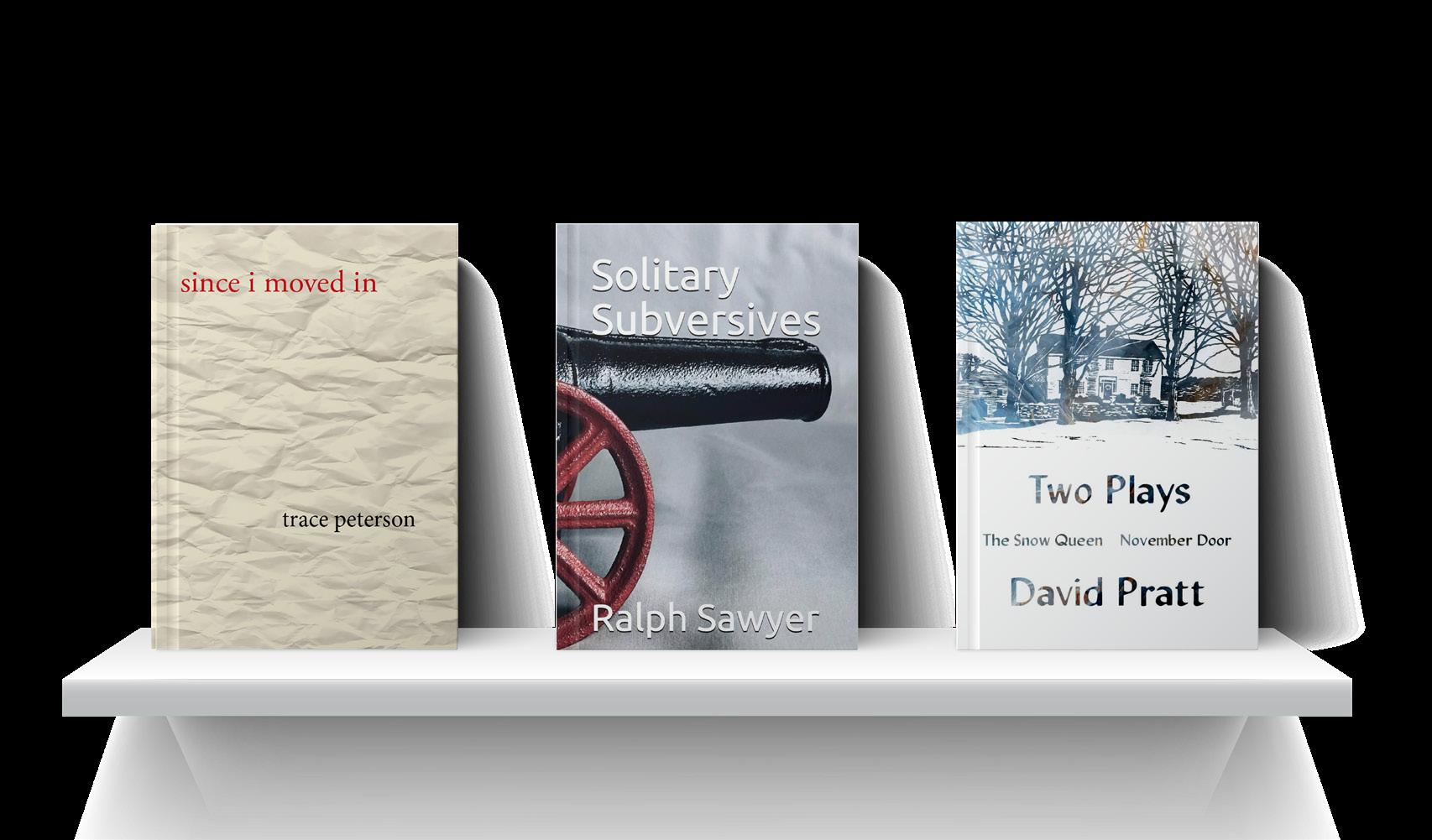

Recent Books by ALUMNI WRITERS

These books have been published or have been brought to our attention in the last year. The editors ask alumni to send updates and corrections to magazine@loomis.org for inclusion in this annual list.

Ralph Sawyer ’63

Assassin’s Quandary: An Intrepid Healer in Early China

Alex Kuo ’57

Mao’s Kisses: A Novel of June 4, 1989

Stephen Paul Sayers ’84

The Immortal Force

Trace Peterson ’96

Since I Moved In (poetry collection, new and revised edition)

Ralph Sawyer ’63

Solitary Subversives

David Pratt ’76

Two Plays: “The Snow Queen” and “November Door”

David London ’86

Pet Peeves: A Comic Strip About How Family Life Can Get Pretty Hairy

Faculty Desks

STU REMENSNYDER

Stuart Remensnyder's desk acoutrements are as varied and eclectic as his interests, which range from his discipline of mathematics and his innovative teaching methods to his expertise as a mountaineer and his love for ice hockey. And don't be fooled by the clutter; there is rhyme and reason to the layers of papers and objects. As with Stu's approach to teaching, if you trust what may seem like chaos initially, it won't be long before everything makes sense, as his students over the years attest. Stu, or "Rem" as many call him, has taught at Loomis Chaffee since 1986, with several stints away to teach abroad, work as a mountaineering guide around the world, and co-own a mountaineering and trekking company. In addition to teaching math, Rem has coached five sports at various levels and contributed in many other roles in the Loomis Chaffee community.

Notes from Stu's children and students decorate his bulletin board.

Precalculus and Calculus books contain Stu's notations for his courses.

In an article for SYA Spain that hangs in his office, Stu reflected on living in Zaragoza with his wife, Nicole, and their two young children.

M&Ms are used in statistics and precalculus classes to practice sampling methods in a delicious and fun way. Stu believes in keeping his students well-fed.

Mugs from Canada conjure memories of 2011–12, when Stu and his family lived in the Frenchspeaking area of

Bathurst, New

Brunswick.

A Peruvian chair made in the city of Cusco features a traditional Incan symbol called a “Tumi.”