24 minute read

EVIDENCE-BASED LP

How Protective countermeasures Actually Work

Judgment is everything for a loss prevention decision-maker. And good choices are a lot easier with good information—hence evidence-based loss prevention (EBLP). As part of our march toward EBLP, it’s important to continue rolling out a common language and understanding in the same way as other professions.

In earlier columns I’ve discussed how critical it is to accurately diagnose the causes and dynamics of a problem to properly treat it using techniques like the SARA problem-solving process. In this column we mention how it is equally important to be able to align and describe how a selected protective countermeasure or treatment actually works to affect a problem. We want to be able to describe an LP effort’s mode and mechanisms of action.

Consider this. In medicine a nurse or physician’s assistant carries out a doctor’s orders. But it is the doctor who has had extensive training in understanding in great detail how a problem occurs and the mechanisms of action of prescribed solutions. That level of training leads to much more precise and cost-effective solutions and helps avoid dangerous and costly side effects.

As we collectively raise the bar in this industry from relatively imprecise decisions to highly informed ones, we are in part talking about decision-makers moving up to the physician level. LP executives will increasingly have a much greater and deeper understanding of problem dynamics and how well LP solutions actually work.

Today, led by a growing number of LP executives, the Loss Prevention Foundation, LP Magazine, FMI, NRF, RILA, and others are coordinating in different ways with the LPRC to use research to eventually provide LP managers the critical process and impact data they deserve.

by Read Hayes, Ph.D., CPP

Dr. Hayes is director of the Loss Prevention Research Council and coordinator of the Loss Prevention Research Team at the University of Florida. He can be reached at 321-303-6193 or via email at rhayes@lpresearch.org. © 2013 Loss Prevention Research Council

Modes and Mechanisms of Action

As part of our research team’s efforts to support multiple retailers, we have attempted to carefully describe how solutions we work with actually affect theft attempts. By knowing how solutions work, we can better determine why or why not and how well they work so we can make improvements.

Our current research ranges from using large datasets to extensive in-store offender interviews to randomized controlled trials (RCTs). In the case of offender interviews, we are increasingly running subjects through stores that we have specially set up in order to determine what countermeasures offenders tend to notice (see), recognize (get), and respect (fear). We can then compare which interventions work best, and how we can boost intervention performance by “tweaking” our deployment and execution.

A huge part of this process is thinking about how these protective treatments actually work. We generally categorize treatment actions into overall modes of action, and then describe the specific mechanisms of action of these modes.

Modes of action are therefore broader and usually mean the countermeasure makes stealing harder for a thief, appear riskier, or makes theft less rewarding. Some treatments can have more than one mode and even multiple mechanisms of action.

Below are examples of some current LP treatments we are to which we are exposing offenders in our CVS StoreLab location, as well as evaluating in larger field RCTs with multiple retailers. In this list I have described how we believe the treatments work in the real world to discourage or disrupt offenders. ePVM Treatment. Enhanced public view monitors have visual and aural enhancements added to increase the likelihood offenders will detect, recognize, and be seriously concerned about the deterrent measure.

The mode of action in this case is centered on increasing the perceived risk of detection, rapid response, and detainment with serious formal and informal sanctions. The specific risk mechanism follows this scenario—if the ePVM is seen and recognized, offenders might believe they’re being currently monitored, and their face will be recognized and directly tied to a specific crime event (what, where, when).

Protective Fixture Treatment. The first mode of action here is focused on increasing the effort required to access or remove an asset. Protective fixtures increase needed tasks, require special knowledge or tools that increase the required time, force or strength, and danger to steal merchandise.

Using blade fixtures as an example, there are several specific effort mechanisms of action in play. First, some offenders perceive the blades are locked in the protective fixture. Second, the fixture slows selection rates down by requiring a sequence of movements to select and remove each pack, adding delay time to select each blade pack. Third, the selection sequence requires two hands to operate the mechanism while removing the blade pack, making item concealment more difficult.

The second mode of action involves increasing the perceived risk of detection, rapid response, and detainment. The specific risk mechanism is the ratchet noise made when the blade shelf is opened to access a pack, which the subject believes may notify others of the protected item’s access.

The third mode of action is focused on benefit denial by limiting the quantity and possibly damaging the asset, thus reducing the value to the offender for personal use or converting to cash. The mechanism of action here is the fact that the protective fixture slows selection rates down by requiring a sequence of movements to select and remove individual items, which delays the time required to select each blade pack, potentially reducing the quantity of items able to be taken in a “safe” period of time.

Annunciator Treatment. The mode of action is centered on increasing risk. There are two specific risk mechanisms in play. First, when a subject moves in front of the product or pulls on a fixture handle, an annunciator behind them generates a human voice greeting to the product and brand, so the subject must deal with a possible privacy threat from behind. Second, the subject knows the annunciator voice notifies others that someone is accessing the protected.

If-Found Sticker Treatment. The mode of action for this treatment is centered around benefit denial. The mechanism of action involves placement of a sticker on merchandise that is designed to create offender concern by threatening that potential fences and public buyers will not desire stolen goods with a difficult-to-remove sticker asking anyone seeing this item in any store other than the one noted on the sticker to notify that retailer using a toll-free number.

EAS Warning Sticker Treatment. Again, the mode of action is focused on increasing risk. The mechanism of action is a sticker designed to create concern in offenders that unauthorized removal of the marked item will result in a loud alarm at the exit, which would likely prompt employee response and potential apprehension.

concept to Action

This listing is just part of our efforts here, but I hope it gets more and more LP experts thinking more and more about our critical industry mission. We’re just getting started, so please let me know your thoughts and suggestions at rhayes@lpresearch.org.

In addition, please contact us if you are interested in participating in this year’s Impact conference at the University of Florida in Gainesville October 14 – 16. The conference brings together over a hundred LP and vendor executives to review past research and brainstorm future projects.

Proactive Online Investigation Tools

Criminals use many online venues to sell stolen merchandise, and eBay continues to be the Internet industry leader in the effort to combat it. In our previous column we reviewed how eBay’s Global Asset Protection team effectively partners with over 300 retailers to proactively identify and remove stolen property listed on our site. We reviewed knowing your merchandise, the factors that affect pricing, and locating potentially stolen merchandise through the investigation of listing outliers. The last section demonstrated evaluating a seller’s business plan to determine if it could be profitable using established costing methods. Many of the tools and techniques discussed in last month’s column may be applied to your search of other online venues. ■ Total Profit—The calculator returns an amount of profit or loss based on your entries and includes the approximate fees charged by Amazon. ■ Evaluate Sales Volume—Is the volume and price of the merchandise realistic? Is this plan sustainable?

To notify Amazon of concerns regarding suspected stolen merchandise, follow the hyper link amazon.com/gp/help/reports. You are asked to provide your email, and select the Violation of Rules report. Provide the name of the seller, the order number, and listing ID. There will be an area to input your comments and concerns.

Locating Merchandise Listings Outliers

Once you have a clear understanding of your high-shrink merchandise and true cost, you are ready to locate current listing outliers. There is a tool called ad hunt’r that can help accomplish this. This free classified search tool provides the capability to search many sites by selection, such as All of Craigslist, Amazon, and others. To use the tool, go to adhuntr.com ■ Select the site you wish to search, ■ Enter a product description, and ■ The tool redirects you to the site and all the current listings matching your description.

Amazon

Amazon provides a site for individuals to list new and used merchandise on its platform. Small individual sellers of used and new goods go to Amazon Marketplace or Amazon Auctions. Marketplace sellers offer goods at a fixed price, while at Auctions they sell merchandise to the highest bidder. Here’s how to find merchandise on their site: ■ Sign in to your account, ■ Enter the product you are searching (be specific), ■ Select item condition (new or used), and ■ Select Brand.

At this stage you will be provided with listings and the price ranges for the search item. Now you can compare your actual cost information to the selling price to locate those listings that are significantly below your cost and promotions. Select the seller to get seller reviews. Select the Detailed Seller Information link to get additional seller information, including how to contact the seller.

Now that you have identified a seller that is potentially involved in criminal activity, calculate the profitability of the seller. Try using this free Amazon pricing and profit calculator. It will help you to develop a better understanding of the selling price points that are necessary for the seller to achieve a profit.

commercebytes.com/cab/tools/calcs/amazon_fee_calculator

■ Item Price—The price listed ■ Cost to Acquire—Calculate the lowest price. Using your cost of an item and knowledge of lowest markdown price, BOGO history, and coupons available, calculate the lowest price at which a seller could obtain the product. ■ Shipping Weight—Determine the actual weight of the product and shipping material. ■ Cost to Ship—Determine the approximate shipping cost by carrier minus shipping charged by the seller.

Craigslist

Craigslist is a classified ads website divided into several sections. Sellers may list merchandise for sale, as well as housing, items wanted, services, and discussion forums.

Dave DiSilva is a member of eBay’s Global Asset Protection team.

Visit us at the NRF Fusion Center during the LP conference 1:30 – 3:00 p.m. June 12 and 13 in San Diego.

Using the craigslist search tool: ■ Select the region you wish to search. ■ Enter a product description into the search bar. ■ The current listings matching your search are returned. ■ Many of the listings returned include a phone number to contact the seller. This information may be used to identify the seller.

To notify someone at craigslist of concerns, use the link craigslist.org/feedback and complete the form, which is sent to customer service. Be specific regarding your concerns. You may also email directly to abuse@craigslist.org.

Other Online Tools

Following are a number of helpful free or low-cost online search tools. ■ blackbookonline.info and virtualgumshoe.com—Both provide free public record searches and direct you to free public record sites based on your input. ■ pipl.com—Provides free public record searches by name, email, user name, or phone. ■ spokeo.com—Searches on email, phone, username, and address.

Requires an annual fee of about $50.

We will post a full list of free or low-cost search tools on our LinkedIn site—eBay Partners with Loss Prevention Professionals—later this month.

linkedin.com/groups?gid=2012550&trk=myg_ugrp_ovr

PROFILE

KirKlAnd’s

STILL GOInG STROnG AFTER nEARLy 50 yEARS

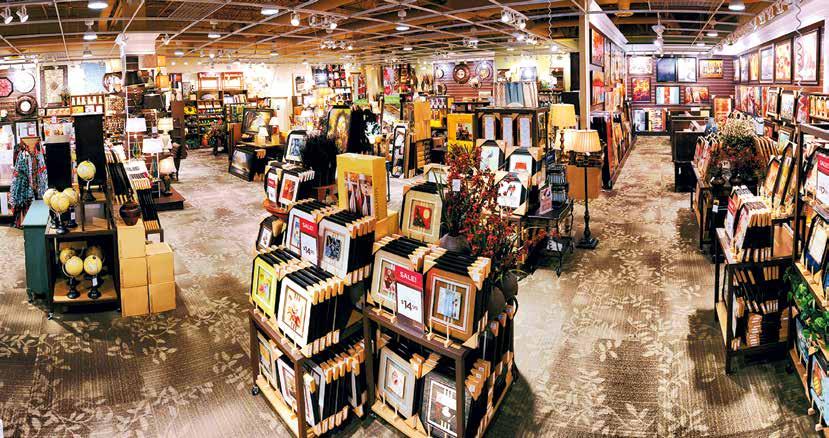

Founded in 1966 by its namesake Carl Kirkland, Kirkland’s admittedly fills an odd niche in the retail world, although it has steadily become more and more mainstream as the decades have passed. Carl Kirland’s original vision for the store originated in Jackson, Tennessee, with a single store that primarily sold gifts and items meant to be gifted. For nearly twenty years, the store lineup stayed more or less the same—to whit, a 1979 catalog bore the slogan, “We sell everything from fruit to nuts,” it’s cover depicting a tin of candy, a jar of almonds, a plush toy turkey, and a plastic thermometer—eclectic, to say the least.

In the early 1980s, as Kirkland’s further expanded, it began to also expand it’s repertoire of products, venturing further and further into home décor item sales space to evolve into what it is today—primarily a retailer of home décor, while still maintaining a supply of “giftable” items, for lack of a better term.

The lay of the land where it pertains to loss prevention efforts at Kirkland’s is fairly typical of a company that was founded by a single individual, and then saw expansion in fits and starts over the years; namely, not much thought was given to loss prevention until its current head of LP, Bill McParland, joined the company eleven years ago.

“My initial field visits found that while the stores had dedicated procedures in place to try to control theft, the field was lacking the core understanding and focus of loss prevention,” says McParland. He is a career loss prevention professional, having held senior positions in LP at such companies as Payless Shoe Source and G&G Shops, and he also holds a bachelor of science in law and justice for good measure. “When I started at Kirkland’s in 2002, we had exactly one auditor and one admin person working loss prevention. We didn’t have a strong LP presence,” states McParland.

Mall Exodus

A big reason that Kirkland’s began to take a more serious look at loss prevention is that in 2005, it slowly began to detach itself from its roots as an exclusively mall-based operation. Up until that time, Kirkland’s had some two hundred odd stores with 95 percent of them located inside malls, primarily in the Southeast.

In a matter of speaking, much of Kirkland’s original LP methodology relied on the mall itself to safeguard its operation. Malls provide a measure of security for tenants; they are well lit, indoors, usually have robust security measures, and more or less allow the tenant to hang their LP hat on whatever the mall is doing. Kirkland’s chief financial officer and the man McParland’s reports to, Mike Madden, muses on the subject of Kirkland’s early mall days. “Malls provided us with lots of security, but you pay for it, and some malls are better equipped than others,” says Madden.

“We started realizing that our customers were coming to visit us. The casual mall walker no longer drove our business. We had become a destination shop,” says McParland of the decision to begin ushering in new off-mall locations. Quite simply, Kirkland’s collectively woke up one day and realized that they had their own following of loyal customers; ones that weren’t tied to impulse buying or random shoppers walking through a mall. So they decided to slowly detach from the mall experience.

McParland adds, “As we started selling larger home décor items, it began to be impractical for Kirkland’s to display the items in a small store footprint and for customers to wheel those items through a mall to get to their cars. We decided that more off-mall stores were the answer. Our customer’s didn’t want to walk through a mall to find us, or park a half a mile away.”

And so McParland found himself at the loss prevention helm of a company that was not only radically changing its product line, but also reinventing itself location wise. No longer could Kirkland’s rely on the security of a mall; they had to look after themselves. “We had to beef up security due to the fact that we were now in standalone locations,” says CFO Madden. “You’re self-contained. You have to deal with that.”

Today, of Kirkland’s 320 stores spread across 34 states, a full 282 of them are off-mall locations, meaning that Kirkland’s is very much in charge of its own security…and destiny…at this point.

Bill McParland found himself at the loss prevention helm of a company that was not only radically changing its product line, but also reinventing itself location wise. no longer could kirkland’s rely on the security of a mall; they had to look after themselves. “We had to beef up security due to the fact that we were now in standalone locations,” says CFO Mike Madden. “you’re self-contained. you have to deal with that.”

Bill McParland

One would think that home décor items wouldn’t necessarily represent an appealing target for the casual thief or especially organized retail criminals, but that isn’t really the case. “That’s a common misconception,” states McParland. “Twenty-five percent of our store items are framed items, such as art or mirrors. They go missing two to four at a time with a price point of between $40 and $200.”

LP challenges

One would think that home décor items wouldn’t necessarily represent an appealing target for the casual thief or especially organized retail criminals, but that isn’t really the case. “That’s a common misconception,” starts McParland. “Twenty-five percent of our store items are framed items, such as art or mirrors. They go missing two to four at a time with a price point of between $40 and $200.”

Recently, some employees were resetting a store display and placed a $400 pedestal sink close to the front door; it was quickly stolen, demonstrating the age-old loss prevention axiom that regardless of the product, if it isn’t bolted to the floor, it’s ripe for theft.

McParland is keenly aware that this sort of pilferage is simply a part of retail business and doesn’t let it get in the way of the customer experience that Kirkland’s strives to create. While McParland could turn your average Kirkland’s store into Fort Knox, he doesn’t much believe in an overbearing security presence within the stores. “We sell products that people want, not products that people need,” he explains. “We want to make every store experience special for the customer. The last thing we want to do is hamper our store teams.”

McParland has also seen a demonstrable shift in pilferage that closely parallels Kirkland’s inventory transformation. Consider that in the past, Kirkland’s stores mainly sold lower cost gift-style items. Yet today, the stores are filled with high-end pieces of furniture and décor items that can cost $500 or more, which changes the loss prevention landscape and the potential losses.

Three years ago McParland decided to implement a store-wide CCTV program. At the same time, he’s decided that technology, such as RFID, really doesn’t work for a store like Kirkland’s, simply because of the uniqueness of the product they sell and the way the stores operate with constant shifting of their product offering throughout the store. “We don’t hold product for a very long time, and our store setups are very fluid,” states McParland.

Internally, Kirkland’s has its share of employee theft and the challenges associated therein. Once again, because of Kirkland’s home décor specialty, certain theft scenarios occur that are peculiar to such a store. McParland describes a recently thwarted theft ring in some of Kirkland’s stores, wherein a group of employees were regularly propositioning customers to purchase goods on a cash basis, essentially removing the register from the equation. “People often come to Kirkland’s to decorate an entire room or home. We had some employees who would try to make them a cash deal on product they were after,” he says. Thankfully, in some of those cases, the employees were exposed by Kirkland’s own loyal customers, who felt ill at ease giving cash directly to sales employees and not receiving a receipt.

McParland also has to deal with the fencing of Kirkland’s products, which occasionally occurs. “Employees have been found taking products out of the store, hiding them in storage units, and then selling them at flea markets or other small mom-and-pop shops that either they or friends may own,” states McParland. “Our customers or other alert employees have actually reported these items for sale.” Once again, this demonstrates the integrity and loyalty of your average Kirkland’s shopper or store teams. McParland’s team also regularly monitors Internet sales of their products on sites like eBay and Amazon, always keeping a close eye on the resale of all things Kirkland’s.

Risk Management

McParland’s full job title is senior director of loss prevention and risk management. The risk management responsibility was added to his plate because that’s where Kirkland’s was experiencing some of its highest losses. “I picked up safety six years ago, and risk management three-and-a-half years ago,” he says, noting the fact that the average Kirkland’s employee is exposed to a potential myriad of safety considerations.

“We sell heavy items, glass items, and other merchandise that can hurt employees. We’ve have numerous 40-pound items, with additional new items hitting the stores weighing up to 100 pounds or more,” states McParland, explaining why a major thrust of his department is now workplace safety. Kirkland’s store employees

aren’t dedicated cashiers, stockroom workers, or retail sales people. All employees are expected to move items, assist in customer carry outs, and reset the stores, often on a daily basis, which exposes them to all sorts of potential injuries.

Due to these considerations, McParland’s team has implemented a comprehensive employee training program, making sure that each employee knows how to properly lift heavy items, handle broken sharp items, and use proper ladder techniques, thus setting policy for company safety in general.

It’s easy to see why things like theft and ORC are on McParland’s mind, but are not the sole focus of his LP efforts. “A picture frame may cost $19.99, but it’s a six-figure claim when someone falls off a ladder trying to retrieve that single frame,” explains McParland. “Ten internal theft cases don’t even approach the financial loss possibility of one severe workers’ comp claim.”

As Kirkland’s product line shifted, so too did McParland’s job focus. Today, he spends as much time dealing with safety and workers’ compensation issues as he does thinking of things like pilferage, employee theft, and ORC. It’s just that important.

Following this line of reasoning, McParland confesses that his CCTV rollout was as much for store employee and customer safety as it was for guarding merchandise and robbery deterrence. Kirkland’s actively uses its cameras as protection for customers and sales associates. Accidents or mishaps can now be examined in excruciating detail to both determine their cause as well as ensure that action is taken to prevent it from happening again.

current Team

Kirkland’s current loss prevention team, headed by McParland, is comprised of both field people and professionals based at the corporate office level. At their Nashville-based home office, one investigator is in charge of monitoring Kirkland’s custom-built exception software program. Another LP supervisor, supported by an administrative assistant, is focused on bad checks, security equipment, e-commerce fraud, credit card scams, and all administration functions.

There are also two field LP professionals—one whose main focus is store and distribution center safety and all aspects related to it, and another who is pure loss prevention. For risk management, McParland utilizes a claims manager and claims specialist to investigate and resolve the numerous incidents reported annually, whether for workers’ compensation, general liability, product liability, property damage, or their fleet vehicle program.

Kirkland’s team at first glance appears to be on the small side, especially considering it has 320 stores across the nation, but that’s because McParland’s focus is based more on a cadre-type group of trainers as opposed to an in-store security force. McParland and his team spend much time on the road, hitting multiple stores, and training the store management so that they can better control their own stores, not only for crime and theft, but for safety-related issues as well.

“The store manager is the captain of that store,” explains McParland. “We train them to a very high level, because they are responsible for everything that happens in that store. We not only show them what to look for, we show them what we look for.” In this sense, McParland’s team isn’t as small as it appears at first glance, considering that each of Kirkland’s 320 store managers also has an LP focus.

The store managers aren’t the only focus of McParland’s training efforts, “We train everyone from the store manager down to our part-time assistant,” he states. McParland’s team leaves no store unturned in their quest to indentify and rectify all of the store’s problems, from ORC all the way down to irate customers. This isn’t to say that Kirkland’s loss prevention team does not have a primary focus on theft and crime. To whit, all of Kirkland’s field people are part of the loss prevention team.

McParland’s training cadre is an interesting loss prevention concept to say the least. While the team itself is relatively light, its main asset is that it imparts a wealth of training knowledge to the individual stores, making it a real heavy hitter. It’s as if McParland realizes that LP personnel can’t be in all 320 stores at the same time, so the best thing that he and his team can do is equip each store with the knowledge it needs to fend for itself, while still

“We sell heavy items, glass items, and other merchandise that can hurt employees,” states McParland, explaining why a major thrust of his department is now workplace safety. kirkland’s store employees aren’t dedicated cashiers, stockroom workers, or retail sales people. All employees are expected to move items, assist in customer carry outs, and reset the stores, which exposes them to all sorts of potential injuries.

There are no cops-and-robbersstyle loss prevention tactics at work at kirkland’s; only a dedicated team of seasoned trainers who share the most important weapon they have— their knowledge—with kirkland’s employees. “We’re all in this together,” states McParland, succinctly painting a picture of his loss prevention and risk management vision.

continued from page 44

having unbridled access to the LP team when required. “We react to what’s draining our profitability. There are so many areas besides theft where this happens,” adds McParland.

CFO Mike Madden adds, “We spend money where it’s needed. Our shrink has remained constant even though we’ve transitioned out of the malls, and there are far more obstacles in locations outside the mall.” Kirkland’s is also actively growing. “We grew ten percent in square footage alone last year,” says Madden. “We’re very pleased, and we continue to adapt.” A ten percent increase in the square footage of Kirkland’s stores is formidable, considering that the country was in the midst of what is supposed to be a down economy. “Normally, we feel the impact of the economy before others do,” adds McParland, alluding to the eclectic nature of the store’s offerings.

On the one hand, Kirkland’s growth presents a range of challenges to McParland’s team, mostly because Kirkland’s isn’t so much growing as it is transforming. The average refund-fraud case is a several thousand dollar event today rather than a several hundred dollar event ten years ago. This is not so much because the crooks are smarter (they aren’t), but because the average ticket item of the product Kirkland’s sells is much higher than it was years ago.

Still, McParland’s team has kept pace with it all, charged with a mission to relentlessly educate Kirkland’s employees, which ultimately brings everyone in as a loss prevention partner, shattering the old adversarial “us-versus-them” LP mentality. There are no cops-and-robbers-style loss prevention tactics at work at Kirkland’s; only a dedicated team of seasoned trainers who share the most important weapon they have—their knowledge—with Kirkland’s employees. “We’re all in this together,” states McParland, succinctly painting a picture of his loss prevention and risk management vision.

ADAM PAUL is a business writer based in Los Angeles, California, and an ongoing contributor to LP Magazine. He can be reached at AdamP@LPportal.com.