71 minute read

Karima Walker

Between sleep and wake, folk and drone, by Sam Walton Photography by Holly Hall

Advertisement

Karima Walker is not a morning person. She admits this to me at 9am Arizona time, squinting into a webcam with breakfast coffee steaming at her side and early light streaming into the room behind her. Dusk, meanwhile, encroaches around me, seven hours and five thousand miles east. “I love it when I’m up early,” she starts to explain from her Tucson studio space, before correcting herself: “Actually, I love it when it’s early and I’m already awake. But I do not like waking – waking is a regular struggle for me. I could probably sleep for days if I didn’t have anything I needed to do. My natural rhythm is to stay up late and wake up late, even though I really wish I could be there for morning.” Perhaps, then, crack of dawn isn’t the ideal time to be talking to Walker, whose own comfort zone – not to mention that of her new album of delicate folk songs intertwined with fragile, burbling tape loops – seems far more rooted in the small hours. Then again, maybe it is: after all, said new record evokes that woozy period of coming round after deep sleep, not yet fully alert but nonetheless hazily aware of one’s surroundings, with its title, Waking The Dreaming Body, signposting that evocation directly. Across its 40 minutes, it addresses that headspace both head on (in its quietly pastoral title track, Walker, breathy and quiet as if only just stirring, sings that “it seems like every morning starts the same way”) and also more obliquely: across large swathes of drone and field recordings, the strange internal logic of the hypnagogic brain is transferred into peaceful abstract sounds that, when assembled, feel like the aural equivalent of huge Rothko canvases: simultaneously edgeless and depthless and still, their meticulously-planned giant form residing beyond the realms of waking intelligibility, but only just. At their most impressive, as on a 13-minute album centrepiece that swoops elegantly from beatific synth surges into dense thickets of reed sounds and out into distant piano and environmental recordings of howling wind, the pieces are restorative and calming, sedate but teeming with life. However, it’s when Walker combines these two forms – swaddling the warm orthodoxy of American folk music in noise and ambient texture, or using non-standard production techniques to subvert otherwise standard songs – that her music is at its most compelling. It’s an approach she first acknowledged while at college in the Midwest around the time of that region’s mid-noughties boom in what was initially called “alt-country”, essentially a retooling of traditional folk and country music with post-rock and experimental approaches. Walker recalls the excitement she felt after hearing Wilco’s A Ghost Is Born while in school, (in)famous for its penultimate migraine-mimicking epic drone piece ‘Less Than You Think’, and talks admiringly of the skewed attitudes adopted by records from around the same time like Master And Everyone by Bonnie “Prince” Billy and Jolie Holland’s Catalpa. “They were the people reinterpreting that tradition, but their trajectory away from it made a lot of sense to me,” she recalls. It’s a trajectory that Walker has followed too. Where some musicians rely on strict compartmentalising of multiple styles, Walker’s preference is for the combinatorial approach. “The model of artists who will put all the lyrical songs on one side and then the instrumental pieces separate is something I like,” she begins, explaining the conception of her album, “but I wanted these two worlds or genres to get an equal amount of attention. “I think that depending on what genre you’re responding to, or what genre representative you’re in conversation with, certain styles get downplayed or featured,” she continues. “Like, from a more lyric-based standpoint, an instrumental song can feel like negative space, or it can feel like something’s missing, which makes sense to me: I’m fascinated by the ways that lyrics and melodies ground us in really helpful ways, and in ways that are really powerful and poignant. But I’m also interested in why our ear then interprets, through the lack of that, new territory or a negative space that frames the lyric-based songs. So in putting them together I wanted to keep some of that tension. I wanted to have the push and pull of where that tension goes when we move from something that feels more definite and structured into a place that feels maybe more dreamlike.”

— No listener left behind —

Occupying the liminal space between two opposing phenomena without diluting the essence or veracity of either seems to be a sort of superpower of Walker’s, whether it’s that space between waking and sleeping or between familiar song and peculiar drone, between the conscious and subconscious or the structured and the stumbled-upon. But that occupation is not borne of striking skilful compromise, like a seasoned centrist politician, but instead comes from sensitive, empathetic juxtaposition, and welcoming difference, contrast and diversity. That feels timely: five days before I speak to Walker, while listening to Waking The Dreaming Body and thinking about what to talk to her about, extremist supporters of Donald Trump stormed the US Capitol in perhaps the most shocking demonstration of the political divisions that the deranged president had stoked while in office. Then, after a night glued to CNN, I returned to her album and, on re-listening, couldn’t help but hear Walker’s embrace of in-betweenness as a super-subtle solution suggestion for America’s discord, a demonstration of how it may be possible for the spaces between the worlds of old American traditionalism and potentially discomforting progressiveness to be hospitable to all-comers, instead of zones that must be fought over and recaptured. I acknowledge to Walker that the metaphor is a stretch, and that I’d be amazed if the intent of her latest record were some sort of political mediation, and she agrees on both counts. But she is interested in the parallels, and perhaps in the hope and comfort, if nothing more pragmatic, that might be sought from viewing global problems through such an alternative prism, comparing them to how she performs her material: “With the lyric and more melodic songs, they’re easy to grab onto, and they make more sense as a single or as something that’s going to draw people in,” she remembers of pre-COVID gigs. “So I felt really aware of what songs could refocus and recentre the malleable attention that an audience is generously bringing to a show, and would try and find the places where I might lose people and where I might draw people in, where I could ground us, and then where I could appropriately push into more dissonant spaces

that were maybe harder to listen to: where’s the threshold where I lose people, and who’s willing to come with me? “Once I find that, we’ll reground together in something that feels comforting or beautiful, and then we’ll go back out, and it feels like this elastic exercise,” she explains. “The reason I talk about that, though, is because there are these questions of hospitality and otherness that I’ve been thinking about – when do people decide that they want to walk away, and where do they remain curious? What can I plant in the noisy places of my show to draw people out in ways that they wouldn’t have expected?” She then tells a story of playing in a fairly sketchysounding rural bar in Oregon (Confederate flags flying, a rodeo happening in the background, cowboys propping up the bar) and using her no-listener-left-behind approach to win over her audience. “And I was like, wow, okay, so it works. It works to find this middle ground and still keep the tension of these differences. And that’s something I will probably keep exploring, because I don’t know if these dualities can always be reconciled in a clean way. But they exist in the same world, so there is, and can be, a way in which they cohabitate…” To be clear, Walker is still talking about musical performance, even if the applications elsewhere are beautifully apparent. But just as she’s sounding at her most hopeful and utopian, she checks herself: “At the same time, there is some serious shit happening that I don’t even totally know how to process, so I’m afraid of suggesting there would be a direct application of my music to the current political situation. I don’t feel at all equipped to do that. But I do think, though, that these political questions of otherness are all about dual coexisting worlds, and that is absolutely a question I come back to all the time.” There is a school of thought that characterises art as an act of reduction. It suggests that Michelangelo’s finished statue of David always existed within the block of stone in front of him, and his creativity lay in the removal of extraneous material until David appeared. Another, by contrast, sees it as an additive process, where the art lies in the combining of distinct notes or colours or words in a unique way. Walker’s approach, perhaps unsurprisingly, appears to lie somewhere in between those two schools, on the one hand whittling away at songs until elegantly succinct folk hymnals emerge, and on the other enmeshing those songs around burble and hiss, drone and dream, to make something fresh, reframed and reimagined. It’s a fragile union, at any time of the day.

Reviews

serpentwithfeet – DEACON (secretly canadian) Josiah Wise had already lived a litany of musical lives before his thirtieth birthday. His childhood involved stints in choirs, first singing classically in the Maryland State Boys Choir, which he found lacking in racial diversity, and then in the choral group at Baltimore City College, in which Black people were far better represented, and with which he went overseas to compete at an international level. The experience sufficiently turned his head to have him, as a teenager, dedicating himself to the dream of becoming a world-class classical performer: rehearsing for hours on end every day, taking lessons in opera singing, and learning French, German and Italian in anticipation of a career that would have him performing arias from across the global songbook. It didn’t materialise. A series of make-or-break applications to graduate programmes were rejected, at what we now know to be a turning point; the moment at which he began to become serpentwithfeet. This was a transformation every bit as physical as musical, as spiritual as sonic. Shorn of the need to pay any heed to the clean-cut conventions of the classical world, he adopted a look that would become his signature, one dominated by an oversized septum piercing and a host of body inkings that, in just about as dramatic a break with his Pentecostal upbringing as possible, included one of a pentagram on the side of his head. He performed similar 180-degree turns in swapping Baltimore for Brooklyn, and in exploring his own queerness. All the while, he was quietly figuring out how to subvert a musical language that he had spent years mastering, only to be told he wasn’t fluent enough for the white classical world to find space for him. He dug deep, studied intently, worked out just how deeply rooted the history of classical in the United States was in the music of his African-American ancestors. He reflected on his own stylistic journey, ruminating on where the neo-soul groups of his college days and his occasional predilection for the gothic could fit in the songs he wrote moving forward. All of which laid the groundwork for what would be a fascinating series of clashes in his early work – between his cerebral, highly academic understanding of classical and the primal nature of the gospel music of his youth, and in his suffusion of centuries-old sonic sensibilities with a lyrical outlook shaped by his experiences as a queer man in present-day America. His enlisting of The Haxan Cloak as his key collaborator on debut EP blisters was no accident; by selecting somebody at the cuttingedge of 21st century electronica he was hiring a sort of futuristic spirit guide who could make sense of Wise’s fundamental push-and-pull between the ancient and the contemporary. blisters was the sound of him working out these contradictions in real time. A quick-fire twenty-one-minute five-tracker that was so much more expansive than the running time suggested, it was ultimately held together not by the production, not by Wise’s scholarly background and not by the myriad influences being thrown into the pot, but by the literal and figurative power of his voice. His pairing of classical inflections with modern effects felt like a genuine breaking of the vocal mould, whilst his conversational approach to storytelling fizzed with wit and glowed with warmth. It played like proof positive that none of the many different hats he’d tried on over the years were ever going to properly accommodate somebody so idiosyncratic –for him to express himself faithfully, he’d need to work in his own image, to his own design. This is something reflected in his position on the outskirts of the mainstream; still a little too weird to command the broad appeal of Frank Ocean, too committed to experimentalism – and even in the era of Ocean and Lil Nas X, perhaps too unapologetically queer – to have a crossover hit. His last album, soil, set down a marker in terms of how intrinsically tied it was to the idea of his ancestry, as well as to his ever-developing relationship with his faith. It was also an album defined by its complexity, taking a nuanced look at the messy intricacies of relationships as well as layering his vocals in a manner that often had him sounding like a choir unto himself. This follow-up, DEACON, feels like an attempt to offer up a more potent distillation of what makes Wise tick, both emotionally and as a musician, whilst recognising that (like the rest of us) he remains a work-in-progress on both fronts. In a further indicator of his ongoing connection with his religious upbringing, it’s named after the position in some branches of the Christian church below that of a priest but above that of a layperson, often acting as a conduit between the two. In an abstract sense, Wise embodies that role throughout: like soil, DEACON is a treatise on queer love and interpersonal relationships; but unlike soil, it seeks less to counsel on the awkward aspects of them, with the deliberate exclusion of any songs that reference heartbreak. Instead, there’s more focus on the little things; it’s as if he’s realised that the biggest political statements can be the simplest. That’s why the gorgeously simple ‘Same Size Shoe’ packs such an emotional punch – it’s a handsomely woozy love song that inflects R&B with dream pop, built around the plainest of observations: “Me and my boo wear the same size shoe.” Lead single ‘Fellowship’, meanwhile, is a clear-eyed paean to the profundity of male friendship, on which he fittingly brings in Sampha and Lil Silva to back him. In general, the compositions here are by a distance the lightest and airiest that Wise has yet put forward. Where soil occasionally threatened to overcook things with perhaps one too many ideas shoehorned in, the musical themes on DEACON are given ample room to breathe. Combined with cleaner, more

restrained vocals and a stepped-down tempo, it means the record – only thirty minutes in length – floats by gorgeously, although repeat listens reveal the songs to be plenty elaborate beneath the surface. With only three features on the album, Wise often approaches the tracks as if determined to accompany himself. The way the pace subtly shifts throughout the hazy ‘Amir’ is a case in point, as is the softly uptempo ‘Sailor’s Superstition’. For an artist whose identity has been so informed by environmental factors – his education, his sexuality, his faith – this is the first release of Wise’s to be heavily imbued with a sense of place – Los Angeles, where he moved around the time the songs began to come together. You can see the palm trees and feel the warmth of the sun with this collection – the change of pace from Brooklyn is palpable. Elsewhere, there remains room for the skilful pushing of Wise’s own boundaries. Opener ‘Hyacinth’ might be the standout, weaving an impressionistic backdrop out of melodic, chiming guitar and deep, throbbing bass over which he smartly pieces together another multipart vocal, effectively duetting with himself as he spins an affecting love story. Comparisons to Ocean have been made readily in the past, but had ‘Hyacinth’ made it onto Blonde instead, you never would’ve heard the end of it. On ‘Heart Storm’, NAO less guests than takes the stage Wise graciously sets for her; the cautious optimism of ‘Old & Fine’, meanwhile, might be the record’s most affecting moment. That track also plays like DEACON in microcosm – this is an album of quiet ambition, one that treads softly in both sound and message. Its minimalism sets it well apart from both blisters and soil, but the spirit of self-discovery remains the same. There’s almost an irony to the fact that, both personally and musically, such a complex character with such a wealth of ability and knowledge seems to have expressed himself most succinctly by stripping away the accoutrements. He has made what is, at its heart, a genuine soul record. 8/10 Joe Goggins FYI Chris – Earth Scum (black acre) When the news of MF DOOM’s passing broke on New Year’s Eve 2020, his legacy of incredible music was clear. Not just his own, but that of the many artists he continues to inspire. A brilliant, if indirect, example of this can be found on Earth Scum, the debut LP from Peckham based electronic duo FYI Chris, which features beats found on a DAT in a skip near Honor Oak Park Overground, labelled ‘FAO: D Dumile’. This anecdote is one of many related to this eclectic album by Chris Coupe and Chris Watson, two men who, one suspects, aren’t short of stories to tell, having spent the best part of a decade immersed in South London’s club culture. Earth Scum is first and foremost a love letter to Peckham, peppered with references to Morley’s chicken shops, nights at Rye Wax, green parakeets, and features from fellow locals like MC Pinty and Simeon Jones of The Colours That Rise. It sounds like Peckham too, vital and pulsating, a hundred different cultural references thrust together in a way that can sometimes be overwhelming but is mostly pretty special, recalling the halcyon days of late-night buses, midweek comedowns and crammed dancefloors. 6/10 Jessica Wrigglesworth as one of London’s most consistently cutting-edge producers. From the versatile electronic textures of fan favourite Clarence Park to his eerie, pulsating score for last year’s indie-horror Daniel Isn’t Real, you can count on him to push boundaries with each new project. Now Clark has shed his skin once again for his ninth album, Playground In A Lake, which is likely to be remembered as his most ambitious, esoteric work to date. Across 16 tracks Clark explores the concept of innocence lost, playing with imagery of a flooded planet. Yet it’s not as downtrodden as that may sound; there are many tranquil moments, inspired by Scott Walker and ’70s synth work. Oliver Coates and members of Grizzly Bear and Manchester Collective lend their hand to the instrumentals, which are occasionally joined by choir boy Nathaniel Timoney, whose vocals help express the themes of childhood and innocence. Tracks such as ‘Citrus’ lull you into a state of calm, while ‘More Islands’ wouldn’t be out of place on the soundtrack to a moody sci-fi film, and the monolithic ‘Life Outro’ closes the record in epic fashion.

Playground In A Lake offers some stunning moments and is likely to be enjoyed greatly by Clark’s most ardent fans, but the casual listener may find the experimental sound design too sprawling. Regardless, he remains a veteran who can be relied upon to never pander to the ordinary. 6/10 Woody Delaney

YUNGMORPHEUS – Thumbing Thru Foliage (bad taste) Morpheus is one of the thousand sons of sleep in Greek mythology, and one of three named in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. He would appear in dreams in human form, as the voice of reason, whilst brothers Phobetor

Clark – Playground In A Lake (deutsche grammophon) Since making his debut in the early 2000s, Christopher Clark has earned his place

(‘Frightener’) and Phantasos (‘Fantasy’) would seek to deceive the dreamer. In essence, it is Morpheus who has the ability to calmly make sense of the chaos of the dreamworld. YUNGMORPHEUS gets his name not from mythology, but because his teenage self would frequently don a pair of round shades like Laurence Fishburne’s Matrix character. However, across his fledgling discography, MORPH plays a similar role to the Greek dream-god: from beneath a blunted dreamworld of grainy beats, he emerges with irreverent bars that wilt personal musings into political commentary. Indeed, behind a veneer of sun-drenched boom-bap, he quips “Fuck all of my racist teachers” on recent single ‘Sovereignty’. Following last year’s standout Pink Siifu collaboration Bag Talk, MORPH’s first 2021 release Thumbing Thru Foliage sees him team up with NY producer ewonee, who does a helluva job. At points, the delectably smoky boom-bap production is the star, and from opener ‘Ride Dirty’, wherein MORPH’s cackles are masked by a smokescreen of G-funk guitar, to glitzing West Coast closer ‘Johnnie Cochran’, the album is a delight that never outstays its welcome. Whilst it is in part the intuitive beat-making that earmarks this as an early 2021 hip-hop highlight, at the centre of it all is YUNGMORPHEUS – in the midst of the album’s abstract dreamscapes, he makes sense of the chaos. 8/10 Cal Cashin

Tindersticks – Distractions (city slang) There was a quietness to Tindersticks’ previous album, No Treasure But Hope, that clearly continued to resonate with frontman Stuart A. Staples, Nottingham’s enduring singer-songwriter and great white hope to sensitive souls in the 1990s who find themselves sensitive souls in the 2020s for an entirely different set of reasons. Album opener ‘Man Alone (can’t stop the fadin’)’ sees Staples burrow deep into this minimalism, crafting one of the most impressive moments in his back catalogue. Sounding like Nick Drake lost in the club, it builds, pauses, allows for bursts of wailing anxiety and then shows its hand in the final two minutes. This sets the pace for an album that uses its smallness effectively, never the wrong side of engaging. Its only misstep is a cover of Dory Previn’s ‘The Lady With the Braid’ that never quite knows what it’s doing – a sparse arrangement doing little other than shedding the song of its interesting parts, its sexuality and menace. No matter: on their thirteenth album, Tindersticks sound warm, close and very human indeed. 7/10 Fergal Kinney

Pauline Anna Strom – Angel Tears in Sunlight (rvng intl) Throughout the 1980s, the music of Bay Area electronic composer Pauline Anna Strom (released under the name Trans-Millenia Consort) opened minds to the possibility of sonically fusing our ancient brains with recording technology to create a singularly beautiful sound. Blind from birth, Strom’s delicate compositions faithfully translate her rich inner-worlds, which were brimming with Dali-like manipulations of the deep past and the shocking present. She would channel this timeless craft through an array of synths she kept in her San Francisco apartment. A devoted Reiki healer, Strom’s work feels therapeutic. For a long time she laid dormant musically, but re-emerged last year to announce her first new release in three decades. Tragically, shortly thereafter, Strom unexpectedly passed away at 74. Angel Tears in Sunlight, then, becomes her parting gift to a world that needs healing more than ever. Across the album’s nine tracks, she blends her fascination with ritualistic organ, German classical, Krautrock and nature to produce an album that feels as cosmic as it does tropical, flowing readily like a leaking ethereal tap. The naturalistic beauty of ‘Equatorial Sunrise’ is eerily idyllic, whereas the humidity of ‘Tropical Rainforest’ is cooled by the pixelated waterfalls crashing through the track’s surface, and ‘Temple Gardens at Midnight’ is the wondrous sound of neurons fading like fireworks in the sky. Angel Tears in Sunlight is a mesmerising final tour of a fascinating mind and a fitting farewell to truly a one-of-a-kind visionary. 8/10 Robert Davidson

Matthew E. White & Lonnie Holley –Broken Mirror: A Selfie Reflection (spacebomb/jagjaguwar) When instinct and serendipity collide it’s imperative to act fast. In those rare moments where something akin to magic presents itself time can feel as though it’s slipping through your fingers like sand in an hourglass. When producer and musician Matthew E. White showed Lonnie Holley a series of demos he’d shelved in 2018, he quickly realised that the Alabama-born artist and performer was the missing piece he needed to transform those sonic sketches into three-dimensional compositions. As White made his way through the instrumentals, Holley searched pages of his notebook for penned thoughts. Led purely by feeling, these lyrics were seamlessly set to arrangements he’d never heard before. Four hours later, Broken Mirror: A Selfie Reflection was captured.

The septuagenarian’s ad-lib approach reflected White’s attitude as he prepared to return to the studio following his 2015 LP, Fresh Blood. Wanting to switch up his songwriting style, White assembled an accomplished septet of musicians which he led in sessions of improvisational freeplaying. Across Broken Mirror, White’s production echoes aspects of how Danger Mouse and the late Richard Swift (who coincidentally produced Holley’s 2020 release, National Freedom) drew inspiration from the psychedelic fusion of jazz and rock during the 1970s. An alluring spell of celestial keys, drawing inspiration from Miles Davis’ early exploration in electric instrumentation that predated his Bitches Brew eruption, casts a brighter glow on anchoring dub beats. Furthermore, woven throughout the music are a variety of immersive motifs and influences from David Byrne’s propensity for dynamic African-influenced beats on ‘I’m Not Tripping / Composition 8’, which precedes the glorious cascading glockenspiel notes that twinkle amidst the rumbling thunder of ‘Get Up! Walk With Me / Composition 7’. It’s difficult to isolate one particular stand-out movement or song from the record. Everything here is a triumph. The immediacy of Broken Mirror’s compositions culminates in a timeless and timely record, and the collaborative partnership between Matthew E. White and Lonnie Holley is a natural one – a case of the right place at the right time leading to the creation of the right songs for this moment. 9/10 Zara Hedderman

Karima Walker – Waking The Dreaming Body (keeled scales/orindal) There’s been plenty of time to think lately. By now we’ve all been stuck inside for the better part of a year, and once breadmaking has lost its charm the only thing you’ve got left is pondering your place in the universe. In Karima Walker’s case, the lockdown has clearly been a period of deep self-reflection – and a pretty productive one at that. Originally intending to record at the tail end of 2019, first personal illness and the global pandemic ended up kiboshing all that, forcing the Arizona native to record this from her home studio instead. Shut off from her usual collaborative way of working, Walker found herself trapped between a yearning for others and the outside and thoughts of her Tunisian heritage and American upbringing. The result is that Waking The Dreaming Body is an album that feels filled with tension channelled into what feels like a forty-minute fever dream. Each song oscillates between rich, ambient textures and melancholy poetry, ebbing and flowing between moments of stark lucidity and blissful ethereal haze. Mostly, Waking The Dreaming Body is a record that somehow feels grown out of Arizona’s deserts and mountains. From the lonely campfire folk of ‘Softer’ to the sound of howling wind that underpins ‘Windows 1’, each song evokes a landscape in some way, inviting you to lose yourself in the sheer open vastness. Trust me – that takes some pretty powerful magic. 7/10 Dominic Haley

Brijean – Feelings (ghostly) The jazzy electric keys, conga-led beats and buoyant bass that colour Brijean’s Feelings all gently lead to the poolside. It nails its sun-drenched atmosphere, as you’d expect from percussionist Brijean Murphy and bassist Doug Stuart, veteran session musicians who’ve used timeless tropicana grooves as the centre of their jams on many a record. Close your eyes, and you could be drifting away on a lilo; listen closer though, and it’s not just carefree escapism that drives this record, but connection and self-assurance. With the sturdy backing of her band to handle the grooves, Murphy dives freely into bolder songwriting and personal reflection. Her voice is gentle but commanding throughout, and her verses are peppered with subtly moving mantras. Like the best party music, it works just as well in a solitary setting, where you can soak up its details. That’s not to undersell the instrumentals though. These are seriously well-crafted tracks, every corner filled with clever flourishes and strong interplay. Stuart gets a moment to shine on ‘Wifi Beach’, with its playful, propulsive bass lick. The interlocked bass and drum grooves anchor the project and act as a response to the introspective lyrics. Feelings is a reach outwards as well as inwards. 8/10 Skye Butchard

Otzeki – Now is a Long Time (akira) Whether crammed inside backroom pub venues or behind the decks of blaring nightclub sound systems, London-based electronic duo Otzeki remain ambivalent as to exactly where their music belongs. The cousin duo, whose early drunken jam sessions were stripped back to guitars and a semi-functional drum machine, have since cultivated a trademark brand of indietronica that succeeds in unifying praise from late-night ravers and sticky basement gig-goers alike. Back with their first new music in two years, the pair’s second album, Now Is A Long Time, reclines into the foundations carved out from their debut by continuing to transmit a socially-engaged message of hope and sanity to a world still struggling to get back to its feet.

Textured guitars and intricate layers of sparse electronic programming spill into ’90s trip-hop and lo-fi house rhythms. Mike Sharp’s cloudbusting falsetto establishes itself from the get-go as it glides above the dense production on ‘Sweet Sunshine’. Rarely does anything sound sedated, the duo’s euphoric sound refracted through rich, permeating waveforms. Flat-out infectious, but always challenging the conventional pop structure, they indulge in hookier grooves on ‘Max Wells-Demon’. Otzeki’s impulse to be catchy yet confrontational sure feels like a thrilling mission statement. 8/10 Ollie Rankine

Middle Kids – Today We’re The Greatest (lucky number) Today We’re The Greatest, the second album from Sydney trio Middle Kids, is touted as a pluckier, more personal outing than their impressionistic debut, as the band decamp to LA for haughty recording sessions and songwriter Hannah Joy adopts a less veiled approach to her lyricism. Personal? Certainly. Joy expresses heavy pangs of sentiment as she gushes through songs written during early stages of pregnancy with her first child (with husband and bandmate Tim Fitz). While unearthing topics of trauma, marriage, and parenthood, they double down on the saccharinity; ‘Run With You’ concludes with audio taken from their unborn child’s 20-week sonogram, in what I can’t quite resolve as an endearing inclusion or a moment that feels more Mumsnet influencer than indie rock. Sonically, the record is also bathed in gooey romanticism, with glossy production bolstering acoustic foundations. The shimmering guitars of ‘Cellophane’ reveal arena-sized dynamism, whilst the slow burn of ‘Bad Neighbours’ provides potential for a lighters-out, loved-up encore. On ‘Lost in Los Angeles’, Joy shows off a powerhouse vocal, but the posturing banjo gives off the same feeling of indie rock cosplay as Taylor Swift’s Folklore. Unfortunately, this artificiality is found elsewhere too – ‘R U 4 Me’ sounds like Noah And The Whale were tasked with writing music for a banking advert in 2009. Although it’s a sunshine-soaked affair, dripping in syrupy sentimentality, the album’s wrestle between indie rock, all-out pop and an almost overbearing pleasantness amounts to an experience that proves a little cloying. 5/10 Tom Critten

For Those I Love – For Those I Love (september) Oftentimes when I listen to music I am transported to another time in my life. I might remember something I felt years ago, or I might have some sort of crazy epiphany, or the long-coming solution to something nagging me in the back of my mind might finally come out of the shadows. I love this about music – that it can take me back to moments that may have seemed insignificant when they happened, but hold wisdom in hindsight. Rarely, though, do I hear an album for the first time and feel myself spirited away into the body and psyche of someone else and our emotions mixed and melded. On his debut album as For Those I Love, master sonic collager David Balfe has achieved this impressive feat. Written over the course of several years, including after the death of his best friend and musical co-conspirator/soulmate Paul Curran, with this album Balfe manages to make me feel the life-sapping and destroying depression and sorrow of loving and losing someone so close. Then, rolling up and down on emotional highs and lows that feel somewhat like being at the mercy of an expanding and raging ocean tide, Balfe’s record resuscitates listeners. He injects life and hope back into me with his own memories. This intimate record uses old WhatsApp voice notes, lines of Curran’s poetry and dance samples intertwined and tangled up with Balfe’s spoken-word storytelling to bring listeners into the heart of his past, from his sometimes dark childhood in a suburb north of Dublin to the highs of knowing real love and brotherhood with Curran and the young men’s other friends. Each track is unique and there’s not a bad song here. Conversations between mates, exclamations about the demise of punk and unique beats wind themselves around the listener’s mind until it is completely claimed, fertile ground for an outpouring of pain and love and the unfairness and bittersweetness of history. The standout track is ‘To Have You’. It’s a reminder that even in sadness the memories of loved ones and better times are something to be cherished instead of pushed away. The song’s energy is rolling and sparkling, bringing to mind the catharsis found on a dancefloor – not a distraction from everyday life but a time to let your more abstract, primal feelings have their moment in the sun. Feel first, think second. Otherwise the darkness will ruin you from the inside out. 9/10 Isabel Crabtree

Jane Weaver – Flock (fire) Recent years have seen Jane Weaver push into spacier territory. 2019 saw the release of Fenella, a reimagined soundtrack for a 1980s Hungarian animation, as well as ambient remixes of her two previous solo albums on Loops of the Secret Society. Her new album Flock is intended as a self-conscious away from those abstract

releases and towards more straightforward pop music – though of course, as a Jane Weaver record, that doesn’t preclude self-professed influences from 1980s Russian aerobics videos and Lebanese torch songs. The album makes good on that promise. Outside of the interlude ‘Lux’, which is all new-age chimes, Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith-style vocal looping and an extremely Tangerine Dream synth flute, every song here will try and stick in your head – and will probably succeed. A particular highlight is ‘Sunset Dreams’, a psych-pop tune with a head-nodding bassline that will have you missing the summer that never was. But for all its retro stylings, Flock is a record that is invested in the production of a better future. Weaver has a clear-sighted sense of genuine optimism which doesn’t neglect the seriousness of the issues that she deals with. On ‘Modern Reputation’, she’s accompanied by a bittersweet 303 as she spins an argument for genuine change. “How many heartaches must we feel? Want to smash the patriarchy, I’m tired of your industry… We must invent some new ideas,” she sings, and you feel like if we put Jane Weaver in charge things could actually get better. 8/10 Alex Francis

Ice_Eyes – Vicious Circles (hypermedium) Life is tense at the moment: overwhelmingly serious, incredibly fastmoving, toxically static. Doing anything can feel pretty difficult under these conditions, but doing nothing isn’t much easier. In this context, this six-track release from Athens production duo Ice_Eyes feels appropriate. It’s hectic, antagonistic, restless, and captures the feeling of stumbling from one catastrophe to the next pretty efficiently. There are several styles at play here, from fairly straightforward, chilly techno to wild-eyed gabber and Rephlex-y breakbeat. The production is hardly subtle – all drunken kicks and gassy blasts of bass –but what it lacks in grace it mostly makes up for in intensity. Opener ‘Hydro’ flickers from one phase to the next on a bed of kinetic synths and a drill-like stalk, while title track ‘Vicious Circles’, the sleekest tune here, gestures towards mid-2000s UK bass music, suggesting that Ice_Eyes could find a comfortable home on one of Hyperdub’s Ø Corsica Studios bills if we’re ever allowed into nightclubs again. ‘Crystalbody’ closes the first side of the record, its most paranoid and uneasy cut by some distance. The second half of Vicious Circles doesn’t quite match up to the standard of the first, the ultra-heavy production becoming a bit of a grind in the absence of new ideas, although fifth track ‘Folded’ includes glimmers of the kind of restrained elegance that would take Ice_Eyes’ sound to a new level. This is an imperfect record, but a compelling one – they’re not there yet, but it feels like Ice_Eyes are closing in on something special. 6/10 Luke Cartledge

Genesis Owusu – Smiling With No Teeth (house anxiety/ourness) It’s early days yet, but Smiling With No Teeth might be the best debut album of the year. The first full-length from Canberra’s Genesis Owusu, Smiling... is a thrilling introduction. Wildly ambitious in scope, there are moments where it snaps into industrial grooves worthy of Trent Reznor, and others where Owusu transforms into an Aussie D’Angelo. His collaboration with Kirin J Callinan, ‘Drown’, sounds like King Gizzard with Bruce Springsteen writing the hooks. Across the record, the Ghanaian-born artist maintains the air of a bandleader, charismatically guiding listeners and musicians alike through fluid changes in style and genre. On some tracks he sings, on others he raps. Elsewhere, he delivers self-aware passages of spoken word, punctuating his verses on ‘Waitin On Ya’, for example, with gems like, “Your alarm can’t disturb you in an eternal slumber, baby.” Owusu’s gift for bars is obvious throughout Smiling With No Teeth. The album’s title alone evokes both the tight-lipped resentment of forced pleasantries and a bloody-mouthed grin of defiance. Meanwhile, on tracks like ‘I Don’t See Colour’ and ‘Whip Cracker’, he ditches metaphor in favour of direct, sharp-tongued attacks on racists, abusers and bigots. It’s lead single ‘The Other Black Dog’ that’s arguably Owusu’s finest moment, introducing the record’s central metaphor of the “black dog” as a symbol for the ills (mental health struggles, racism, the general chaos of the world) that haunt Owusu and serve as a constant thread through the album’s shifting styles. A triumph from top to bottom, Smiling... sets the stage for Owusu to become a potentially generation-defining star. 9/10 Mike Vinti

Sons of Raphael – Full Throated Messianic Homage (because) The title of this first full-length from West London duo Sons of Raphael suggests little interest in doing things by halves, and comes complete with a frequently preposterous and occasionally dubious backstory that veers from The Exorcist (they were run out of the chapel where they filmed the video for ‘Eating People’ and denounced as devil worshippers) to Uncut Gems (they staked

this record’s entire budget on a basketball game, won, and promptly spent the take on drafting in a 35-piece orchestra). Clearly capable of talking the talk, Full Throated Messianic Homage also suggests a capacity for walking the walk, playing like a woozy whistle-stop tour through the last decade or so or off-kilter psych-pop. ‘On Dreams That Are Sent by God’ recalls Wondrous Bughouseera Youth Lagoon, while the spectre of MGMT’s Congratulations hangs heavy throughout, especially on ‘He Who Makes the Morning Darkness’. It is unquestionably indulgent, and occasionally a sharper editor would have worked wonders – ‘Let’s All Get Dead Together’ is a pace-killer – but there’s always room for a couple more genuine characters in this corner of this musical world. Sons of Raphael have started strongly, both looking and sounding the part. 7/10 Joe Goggins

William Doyle – Great Spans of Muddy Time (tough love) For a tour of perfectionism in music, William Doyle’s Your Wilderness Revisited could have written the guidebook. Layers of sonic ecstasy exposed a painstaking attention to detail within the strange shadows which the record cast on suburban life; a rainstorm of synths, labyrinthine guitars and playful arpeggios like electronic artillery paid their uncanny debts to Doyle’s native suburbia, composed like a giant game of KerPlunk. It was a psychic reset from his years writing as East India Youth, catapulted into a critically-lauded world beyond his knowing, with a few remarkable albums under his belt; here was a world he knew intimately. The second album released under his own name, Great Spans of Muddy Time, is, in many ways, Wilderness Undone – a body of work as remarkable in its sound as in its composition, caught in between adventure and apprehensive relaxation. Dotingly named after a quote by Monty Don in an episode of Gardeners’ World, the record dives into the sludgy endlessness of mental health’s disorientations and lockdown’s idiosyncrasies; channels occasionally drop out and crackles of feedback consume gorgeous homespun melodies, all the result of a hard drive failure where his original recordings were lost or saved only to cassette tape, liberated from his ability to tamper with them. Even the accompanying artwork is a paean to the notion of the artist stepping back. ‘The Floating Feather’ by Dutch painter Melchior d’Hondecoeter is unofficially named for the detail seen on the water beyond the artist’s own meticulous studies of birds. From the rich arrangements and approachable art-pop of lead single ‘And Everything Changed (But I Feel Alright)’ to the crisp catchiness of Zapotec-era Beirut on ‘Nothing At All’ that eddies and swirls into malaise, or the harboring electronic fug of ‘A Forgotten Film’ and bass swells of ‘Shadowtackling’, Great Spans jettisons reference for dizzying experience. Foraging further into the wilderness, Doyle has uncovered a maximalist Lynchian heaven from the undergrowth. 10/10 Tristan Gatward

The Natvral – Tether (dirty bingo) Palate cleansers. Fancy restaurants can’t get enough of them, but in music they’re a completely foreign concept. Until now. Tether, the debut album from The Natvral, attempts to bring the idea of the cleanser into the world of indie rock, one reverberated guitar strum at a time. The new project by Kip Berman (formerly of Pains of Being Pure at Heart fame) offers up nine tracks of super soft-scooped Americana, expertly cleansing the remnants of his shimmering indie past with each and every mouthful. While successful in creating a clean slate, the record does suffer from its vanilla nature. At first there’s real promise. The soothing organs of ‘Why Don’t You Come Out Anymore’ and ‘New Year’s Night’ shine bright, perfectly blending the concept of the cleanser with music that’s enjoyable in its own right. However, these moments are few and far between. Due to the rest of the album’s distant hollowness things quickly become somewhat unmemorable, leaving the listener with nothing more than an aftertaste of Neil Young. With Tether, The Natvral has succeeded in creating the world’s first aural palate cleanser, but at what cost? Sometimes you’re just better off with a bit of flavour. 6/10 Jack Doherty

Cheval Sombre – Time Waits for No One (sonic cathedral) Eight years on from his last solo release, New York poet and songwriter Cheval Sombre (real name Chris Porpora) returns with Time Waits for No One, a collection of spacedout ballads that aims to encase listeners in a sonic sanctuary. By no means a creation of the pandemic, but somehow fitting to the times all the same, the record is an homage to slowing down, to encountering the world without rush or expectation. Written over many years, the record comprises eight original songs and a dream-like cover of Townes Van Zandt’s ‘No Place To Fall’. The music is anchored by Porpora’s hypnotic vocals alongside simple open-tuned acoustic guitar, encircled by keyboards, strings and cosmic effects. Gentle and repetitive, the songs have a way of bleeding into each other,

running with ideas for longer than might be expected, so the listener might lose track of where the song began and when it might end.

Time Waits for No One feels like the hazy space in between dreaming and waking – calm, ethereal, and at times unmemorable – but perhaps this was Porpora’s intention. “Music doesn’t have to be so ambitious all of the time,” he said of the record. “There is a place in music where we might suggest something eternal, a refuge.” That he has certainly achieved – close your eyes and let yourself sink into it. 6/10 Katie Cutforth

Dry Cleaning – New Long Leg (4ad) Dry Cleaning’s debut album, New Long Leg, is both a lockdown record and an unsettling reminder of pre-’rona normality. On the title track, vocalist Flo Shaw’s spoken-word lyrics deal with sunburnt skin and travel toiletries. In the slogging yet slick ‘Leafy’, Shaw muses about “a tiresome swim” and “knackering drinks”, among other workaday activities and distant memories. The mood she succeeds in creating isn’t one of nostalgia or sentimentality, but one of weariness and, to a lesser extent, new found appreciation for the mundane. Shaw’s off-beat selftalk and stream of consciousness vocals encourage us to consider that while lockdown has been crap at best and devastating at worst, there were elements of life before that are better off consigned to the past, and others, dreary though they may be, that ought to be held dear.

New Long Leg wasn’t written or even demoed in lockdown, but, aided by the introspection of the resultant global standstill, it did come to life during that period. While guitarist Tom Dowse used the time to experiment with noisier, more aggressive guitar tones and bassist Nick Maynard played around with fine and bouncy basslines, Nick Buxton, the band’s drummer, tried out drum machines. Shaw, on the other hand, tightened her lyrics, explaining that, “I found the lockdown played into some of the themes I was interested in anyway: living in a small world, a feeling of alienation, paranoia and worry, but also a joyful revelling in household things.” In June, the band spent two weeks in rural Wales at producer John Parish’s Rockfield Studios, where, guided by his expertise and enthusiasm, they recorded the album. The album that emerged is a record of greater confidence and refinement than Dry Cleaning’s two EPs, Sweet Princess and Boundary Road Snacks. Here, triviality and meaning compete to create a compelling portrait of ordinary life, one littered with acerbic wit, intricacy and yawning negative space. Nowhere is this demonstrated better than on the album’s opener, ‘Scratchcard Lanyard’, a springy song disconcertingly layered with abstract lyricism and upbeat melodies. On the track, Shaw laments the superficiality of the social media age. No doubt inspired by the topsy-turvy “new normal” of lockdown, she reminds us that commodifying our experiences for the sake of Instagram and increased social capital is simply “to do everything and feel nothing.” 7/10 Rosie Ramsden

Django Django – Glowing in the Dark (because) Writing a band’s bio is a very subtle chiseling job: to master it, it’s necessary to balance the most compelling storytelling with fascinating, truerthan-true pieces of information to render an idea of natural talent mixed with the group’s hard work. It’s thus peculiar to learn from Django Django’s official introduction to their latest effort that “several tracks for Glowing in the Dark were written specifically to fit precise junctures in their set (which is, as Vinny says, already crafted ‘to draw a line of links from acoustic stuff through the electronic, rhythmic thing, through to something more raucous and rockabilly’).” What good can an album of self-described fillers really be? Yet, the British four-piece have managed to pen another excellent LP – their most distinctive and mature so far, anticipated by singles remixed by, amongst others, MGMT and Hot Chip, and featuring the vocals of Charlotte Gainsbourg (on ‘Waking Up’, one of the best songs here). Multifaceted and polyhedral, the sound of the thirteen tracks is cohesive and coherent, blending together some of the most interesting genres of the last six decades – psych-pop, space rock, garage, krautrock, Madchester, the ’00s indie revival, even folk – with ease and lightness, like Psilocybin-induced visions. Just like the luminescence emitted by a substance that has absorbed the energy around it, Glowing in the Dark beams softly, sparing us from the obscurity of present times. 9/10 Guia Cortassa

Julien Baker – Little Oblivions (matador) A lot has happened to Julien Baker since the release of her last album, 2017’s Turn Out The Lights. The Memphis musician formed supergroup boygenius with Phoebe Bridgers and Lucy Dacus. She reassessed her attitude to alcohol and, burned out by touring, she returned to college to complete her degree. Returning to the studio upon graduation she adopted a band approach for third album Little Oblivions. The themes of booze, bars and faith remain true to her confessional style of writing but she’s swapped the fragility of her

earlier releases for a more full-blooded sound. The tracks come wrapped in synths, banjo and drums that she mostly performs herself. Stylistically the change isn’t as dramatic as might have been anticipated. She was already adept at creating build and using dynamics, which have just become more dramatic here. This follows the musical arc of Bridgers, with whom there are obvious similarities on ‘Bloodshot’ and ‘Favor’, and who guests on backing vocals alongside Dacus. There’s also plenty of continuity, with ‘Crying Wolf’ and ‘Song In E’ having a stripped-back sound that prioritises synth and piano. In widening her sonic palette, however, she’s given herself more scope for welcome emotional catharsis. 7/10 Susan Darlington

Meemo Comma – Neon Genesis: Souls Into Matter² (planet mu) Neon Genesis Evangelion is a ’90s anime TV show about a sad boy who pilots a giant robot – kind of. Owing to its use of imagery lifted from mystical traditions (crosses, the Kabbalistic tree of life, the peppering of names like Adam, Eve and Lilith) the post-apocalyptic premise is so steeped in ambiguity that nobody can really say what it’s “about” other than the search for higher meaning in an entropic world. Having studied Kabbalah to connect with her Jewish identity – as the ancient-modern cadences of Kenji Kawai’s Ghost in the Shell score played quietly in the background – Lara Rix-Martin, aka Meemo Comma, cryptically addresses the same eternal question with Neon Genesis: Souls Into Matter². Superficially, the LP bears a closer resemblance to her first Meemo Comma album, Ghost on the Stairs, in its emphasis on computerised beatmaking. While Rix-Martin has always been a gifted musical storyteller within the often immutable and tricky mode of ambient music, ‘Neon Genesis Title Sequence’, ‘Tohu & Tikun’ and ‘Tif’eret’ benefit from inventive exercises in drum and bass, dub and techno, tied neatly together by the album-length thread of looped vocals and angelic choruses.

Neon Genesis Evangelion’s final episode ends on a note of selfactualisation amid all the chaos; a momentary release that feels woven throughout Souls Into Matter² in name, sound and concept. It feels like the result of an artist dedicated to exploring her own selfhood through art, which is all you can ask of an album featuring cosplay on the sleeve. 7/10 Dafydd Jenkins

Mogwai – As The Love Continues (rock action) 25 years. That’s how long Mogwai have quietly (and loudly) been doling out guitar-heavy detonation at the stamp of a Stuart Braithwaite overdrive pedal. After all that time, there’s undoubtedly a method to Mogwai, but the beautiful noise they’ve made over the years has only stood because of their dedication to reimagining the potential of sheer volume and plunging walls of noise.

As The Love Continues has all of their hallmarks (the plaintive lulls, the booming peaks, the whirling anger) but as tried-and-trusted as those structures are, there are a few unexpected subtleties that make Mogwai’s tenth album a surprising listen. ‘Pat Stains’ and ‘Drive The Nail’ provide the flashes of the calm-to-crashing rage that made 2017’s Every Country’s Sun feel so tense and brash. ‘Fuck Off Money’ and ‘It’s What I Want To Do, Mum’ go deep to refresh the tumbling, vocoded melancholy of the band’s Happy Songs for Happy People era, and ‘Midnight Flit’ erupts into a sweeping crescendo of guitar and orchestra that clashes, soars and plummets to blockbuster effect. But it’s the chiming delicateness of lead single ‘Dry Fantasy’ that really hits home. Dreamy and melodic, it drifts like the opening bars of an M83 opus, switching out the power chords for raining synth and chunky reverb that’s drizzled on deliciously thick. It’s Mogwai as you’ve always heard them, but also as you’ve never heard them before. Three decades in, and their evolutionary guitarmageddon still continues to surprise. 8/10 Reef Younis

Fimber Bravo – Lunar Tredd (moshi moshi) A magnetic force at the beating heart of protest music for nearly half a century, steel pan wizard Fimber Bravo speaks to the resistance with a new compulsion on the opening seconds of Lunar Tredd, strengthened with experience: “They ban our street voice and they choke we, we still shout ‘you can’t control we’.” The pulsing metallic beat and undulating grooves of his first new music in seven years tumble around his politics, brazenly collaborative and emboldened in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement across the globe. His production sounds more joyous than ever, weaving his own fusion of afrobeat and highlife with the glossy sheen of Western synth-pop and electro from the album’s family of players. It’s likely that you’ll have heard Fimber Bravo’s music in some capacity before, if not his first widely-released solo album in 2013, Con-Fusion. The melody in Gwen Stefani’s ‘Hollaback Girl’ was snatched from his 20th Century Steel Band’s ‘Heaven and Hell is on Earth’, sampled by Salt-N-Pepa, the Black Eyed Peas, LL Cool J and – best of all – J Lo’s

‘Jenny From The Block’ (“Everybody’s got to earn a living”). He led fellow nightclub musicians on Steel An’ Skin’s ‘Afro Punk Reggae Dub’, steeling reggae and disco rhythms with his Trinidadian-by-South London twists, turning seven minutes of hypnotic funk into a veritable cult classic.

Lunar Tredd is a carnival at its heights and at its most reflective. The only constant across its twelve tracks is Bravo’s steel pan and refreshingly easy vibe, offering a deep inhalation above its neon-drenched interior. Senegalese percussionist Mamadou Sarr’s propelling rhythmic drive harvests the record’s textures, from the wallowing introspections of Susumu Makai-written ‘Santana’s Daughter’ and neighbouring ‘SingO’, which recalls a Woodstock-era Santana on its bouncing thrum. Alexis Taylor’s synths reverberate around psych meditations, beautified by The Horrors’ Tom Furse and Vanishing Twin’s Cathy Lucas on ‘F.Pan Landing’. As with many of the new sounds entering the world in its current paralysis, dance music reverberates with a particularly uncanny echo. Even with the spellbinding bass of ‘Hiyah Man’ and addictive drones of ‘Tabli Tabli’, Fimber Bravo’s weathered vocal is the centrepiece, unifying the record’s strands of tradition and experimentalism, from Calypso and West African Kaiso to sickly sweet autotune. On Lunar Tredd he leads both a drowsy dance and a festival elegy, longing to be distilled. He’s a master of his craft, and it’s best when it’s all him. 7/10 Tristan Gatward the album cover’s shot of Erez in an oversized jacket, this record knows what it’s about. It represents childhood like a child would: by being loud and bombastic, full of energy until it tuckers itself out. Whilst Erez often gets compared to Björk, the artist I keep coming back to is Kendrick Lamar. Like the Compton prophet, Erez knows that her voice can be powerful; not just in a political sense but in a literal musical one. Her delivery goes from childlike to confrontational, fitting playground anthems and punctuating insults. Production often sounds like a mid-2000s ringtone, all simple beats and a bass that chases you. The crux of the album is ‘NO news on TV’, a playful, ironic ditty toward the end of the album that’s about wanting to distract ourselves, needing to consume so we don’t think about what we’ve consumed. I’m not sure it’s the album of 2021, but it’s definitely the feeling of it. 8/10 Sam Reid

Ocean Wisdom – Stay Sane (beyond measure) So much of the talk about Camden rapper Ocean Wisdom the past five years has been about the rapidity of his flow. And it’s true: he’s got lungs like a whale and officially spits words quicker than Eminem, according to Guinness World Records. That skillset saw him attract collaborators as esteemed as Method Man and Dizzee Rascal, and comparisons to speed-merchants like Busta Rhymes. While there are some impressive sprints on his fourth album, it’s not simply an exercise in flashy velocity. In fact, it’s when Stay Sane is cruising that it’s most compelling – think Childish Gambino rather than, say, Twista. Single ‘Drilly Rucksack’ is a case in point – the fictional tale of a magical rucksack that shields its owner from the evil of Tories, albeit in a violent way – where Wisdom artfully glides between gears and modes. Opener ‘Gruesome Crimes’ is similarly ear-catching, marrying goofy U.S. college rap musicality with a British sense of humour. Maverick Sabre adds a soulful flourish to ‘Uneven Lives’, an ode to the healing qualities of time off and time away. It’s ‘Racists’ though, featuring the recognisable Novelist, that’s perhaps the most arresting moment; an honest, depressing and lasting reflection on British bigotry: “Racists they come and won’t go… I hope you drop down dead while you’re shoveling cocaine up in your nose,” he rasps. For one so quick with his delivery, it’s now that Ocean Wisdom’s steadied the pace that his output grows in power. 7/10 Greg Cochrane

Virginia Wing – private LIFE (fire) It isn’t immediately obvious that private LIFE, Virginia Wing’s fourth album, is their most engaging album to date. Anyone might think it’s ‘just’ Ecstatic Arrow Mk. 2 – and neither artist nor listener would be to blame, given how the Manchester group’s 2018 release represents such a strident leap forward that it would be inadvisable to do anything too off-piste for the follow-up. The two LPs are linked by a similar strain of ‘fourth world’ production, covertly masking what is essentially pop in the avant tradition of Peter Gabriel. Vocalist Alice Merida Richards’ speaksing approach fits the bill too, sitting at a Laurie Anderson monotone until errant emotions permit a melodic flight to the upper register, complementing her lyrical desire for escape. “Paradise became a motorway,” she sings on ‘99 North’, neatly summating the thrill of movement now that the prospect of far-flung travel

Noga Erez – KIDS (city slang) If we have anything in common it’s that we were once all children, and Noga Erez’s second album seems to argue that we still are. From the title track addressing “Naughty boys, now you naughty men” to

has all but vanished – deeply resonant to someone who spent New Year’s Eve 2020 in joggers with the Hootenanny, who fears that 2021’s celebrations might somehow shake out to be even worse: “I’m reaching, I’m holding out, holding out for something.” Aside from its tighter presentation of Virginia Wing’s existing sound, private LIFE benefits from a doubled-down dedication to the specific wild abandon only pop can offer. ‘Moon Turn Tides’ swaggers like a reimagined version of Gal Costa’s ‘Relance’ remixed for club consumption by Timbaland, its wheezing organs playing against stomping marching band horns. ‘St. Francis Fountain’ and ‘Half Mourning’ harken back to Yellow Magic Orchestra, sealed with the sophistipop gloss of saxophonist Chris Duffin, his smooth licks swirling across the mix. All this, and it’s still difficult to say why private LIFE is as great as it is. Overt comparisons to past work seems detrimental to what a group produces presently, but in Virginia Wing’s case, what they’re doing right now elevates their career as a whole. They’ve outed themselves as having been onto something all along. 9/10 Dafydd Jenkins

Arab Strap – As Days Get Dark (rock action) According to Aidan Moffat, As Days Get Dark is about “resurrection and shagging”, “hopelessness and darkness”. As if that wasn’t what every Arab Strap album was about. Nobody does horny, hungover, misanthropic filth quite like Moffat and Malcolm Middleton. This is their first album since 2005’s The Last Romance, but their aesthetic is so singular that it feels like they’ve just picked up directly from where they left off. Perhaps this is helped by their consistent activity throughout the intervening years – solo albums, collaborations, documentaries, the lot. They’ve kept busy, and they sound it – this is the reanimation of a merely dormant project, not a dead one. There’s little here which will surprise long-term Arab Strap fans, but that’s not necessarily a criticism. Most of the music is built upon an artful tessellation of Middleton’s arpeggiating guitars and creeping drum machines, with Moffat delivering his grubby monologues over the top. The atmosphere remains as sticky and dank as ever – you can practically hear the sweat dripping down the flanks of each track – but Moffat’s characteristically seedy vignettes now play out among the soft furnishings of middle age (“In Tesco with your buttons undone, I saw you; hand in hand as we do the school run, I saw you”). Not that this jars with the rest of the Arab Strap catalogue: even in his twenties, he had a prodigious talent for being a dirty old man. He’s really grown into it now. 7/10 Luke Cartledge

Indigo Sparke – Echo (sacred bones) Although it’s by no means all you need to know about Indigo Sparke, a good place to start is that she’s the protege of Adrienne Lenker from Big Thief. As expected, this means her debut album is full of reverbdrenched lonesome melancholic balladry, songs about solitary women smoking while walking down desert(ed) highways, plenty of spectral fuzz from simple electric guitar strums, and acres of empty space. And when it works, its tremendously affecting, full of small-hours half-cut wistfulness and intimacy: the ghostly ‘Bad Dreams’ feels like an excerpt from an epic murderballad, its lyrical brutality underpinned by its delicacy, and the final third of the album makes for a gorgeous triptych of poise and atmosphere, the combination of battered background piano and brittle vocals on closer ‘Everything Everything’ is particularly haunting. Unfortunately, though, Sparke occasionally pushes too eagerly on the button marked “eerie” and comes out a bit am-dram: midway through ‘Dog Bark Echo’, she whispers, urgently, “Listen! Do you hear? Howls! A beast is opening its mouth!”, and then she howls. On ‘Golden Age’, too, multi-tracked “oohs” and “aahs” yearn to evoke the sort of mysterious quasi-paganism/profound sadness at which PJ Harvey often excels, but the delivery is too self-aware to believe there’s much genuine abandon going on here. Were Sparke to lean into the sparseness and interiority of her songwriting, Echo would be consistently spine-tingling. As it is, although there’s plenty to admire here, it’s too precious to be perfect. 6/10 Sam Walton

Lady Blackbird – Black Acid Soul (foundation) There is very little about Black Acid Soul that is identifiably 2021, nor any other year. Marley Munroe, the woman behind the Lady Blackbird moniker, announces her arrival with a debut album that is difficult to believe is not the culmination of a six-decade career, such is the depth of wisdom, expression and control in her voice. Coming nominally from a jazz background, this album does not belong to a genre, but to a singer with the scope to oversee where different genres meet. She takes a set of eleven tracks – seven of them cover versions – and finds truths that apply to her, so that in turn they may apply to us too. ‘Beware the Stranger’ is a version of a 1973 track by The Voices of East Harlem, and while Munroe’s version channels just a taste of the song’s gospel funk roots with its choral backing,

all accompaniment is powerless in the shadow of Lady Blackbird’s towering vocal. ‘Collage’, meanwhile, is a track with a rock history (penned in 1969 by the James Gang) and yes, there is a driving momentum to this arrangement that points to where Munroe could move in the future should such conventions be of interest to her, but what is clear is she will not be knocked off course before she has even begun. It is not just that Munroe has a powerful vocal, or that she can convey great, centuries-old pain and struggle, but that she can eke out nuance from every turn of phrase; it is often possible to read her delivery of a single word in multiple ways, she layers such meaning into her performance. Munroe realises that there is more to be said by someone who can tear the house down with ease, when they choose not to. 8/10 Max Pilley

Blanck Mass – In Ferneaux (sacred bones) On his latest project In Ferneaux, Benjamin John Power suspends us in limbo. Much of his previous work as Blanck Mass derives its power from the brute force of its sensory overload – this is incredibly visceral, physical music, designed to be played out over churning crowds, terrified and exhilarated in equal measure. In Ferneaux mostly breaks from that mould, mirroring the retreat we’ve all had to make from such spaces in the past 12 months, yet traces of previous sociality are discernible in every note. It’s those traces that make up this music’s central eeriness – its tangible absence of something beyond the familiar – and make it so intoxicating. The raw components of the record are recognisable enough – Power’s hyperactive synths are pursued by his customary snarls of digital distortion and white noise, intermittently broken up by scatty field recordings and disarmingly open piano chords – but it’s their presentation that’s so captivating. It plays out over two “phases”, each 20 minutes long and dense to the point of disorientation. One could just as easily describe the album as having 20 “tracks” as two, although none of it is neatly separable into discrete segments. The record starts with the opening arpeggios of ‘Phase I’, which shift quickly between barely-suppressed tension and not-quite-release, two modes of being which I’ve definitely had to get used to as the pandemic has ebbed and flowed. It’s a compelling opening salvo, a sort of apocalyptic game show theme that soon starts to decay and break apart, Power never having been an artist to let an idea outstay its welcome. Just as the loops are about to collapse entirely, a thunderous four-to-the-floor seizes the initiative, and we’re briefly plunged into the middle of an equally end-times psytrance rave. When this recedes, we find ourselves on a shoreline somewhere, boats and buoys clanking in the surf, a welcome reprieve. Much of this phase continues accordingly: fleeting moments of tranquillity interspersed with corrosive heft, snatches of genuinely arresting beauty that are swept aside by torrents of something far more ferocious and unyielding. A decade’s worth of field recordings, captured over the course of Power’s travels with his solo music or as one half of Fuck Buttons, ground his production in the material world, lending the album a certain physicality that makes the demonic synths and broiling sheets of discord all the more invasive and unavoidable. There’s something about the record’s restless pace and distracted intensity that conjures up the feeling of grasping at half-memories in moments of desperation, or indeed of staggering through the pathologies of our embattled present themselves. It’s at once horrifyingly brutal and even more horrifyingly familiar. ‘Phase II’ begins just as savagely, all clipped screaming, indistinct chatter and long-wave interference, before the noise subsides to allow an earnest, yarn-spinning monologue into the foreground, framed by elegiac pads and flecks of reverb. It’s tempting to describe this passage as dreamlike, but that’s to slightly underplay its semi-conscious, somnambulant quality; it’s more evocative of the experience of beginning to wake up on an already-busy morning, the conversations of passers-by outside or the natter of a clock radio wheedling their way into your slumbering brain. Like those brief periods of half-sentience, this section finishes all too quickly, and we’re in the throes of hiss and corrosion again, passing swells of discord and pacification as we’re dragged along by the unrelenting current. Power doesn’t let up at any point – it’d feel rushed and messy were each passage not so rich and minutely detailed. The album’s press release describes Power as working with “the immanent materials of the here-and-now”. This doesn’t quite capture what’s going on here. Perhaps there is a sense in which the sounds that populate the record are immediate and inherent to the present moment, but only to the extent that they were literally to hand at the time, having been recorded earlier or extracted from equipment that Power already had. Their prevailing affective quality has much less to do with the here-and-now than it simultaneously has with the recent past and a hoped-for near future. It regards pre-pandemic society without any real nostalgia or sentiment, more a clear-eyed observation that the previous status quo has been irrevocably altered. What’s so powerful about it, though, is its sense that elements of that status quo will be returning, and not all of them good. Its eeriness, its central absence, is at once temporary, as it looks towards a future to which some of the things we miss will return, and fundamentally permanent – after all, there are a lot of things, namely an abjectly large and growing number of people, that will not be coming back when the virus finally loosens its grip. For those of us lucky enough to be in limbo for a while, this is a moving, unsettling piece of work from a singular talent; for far too many others, it may at least be some form of tribute. 9/10 Luke Cartledge

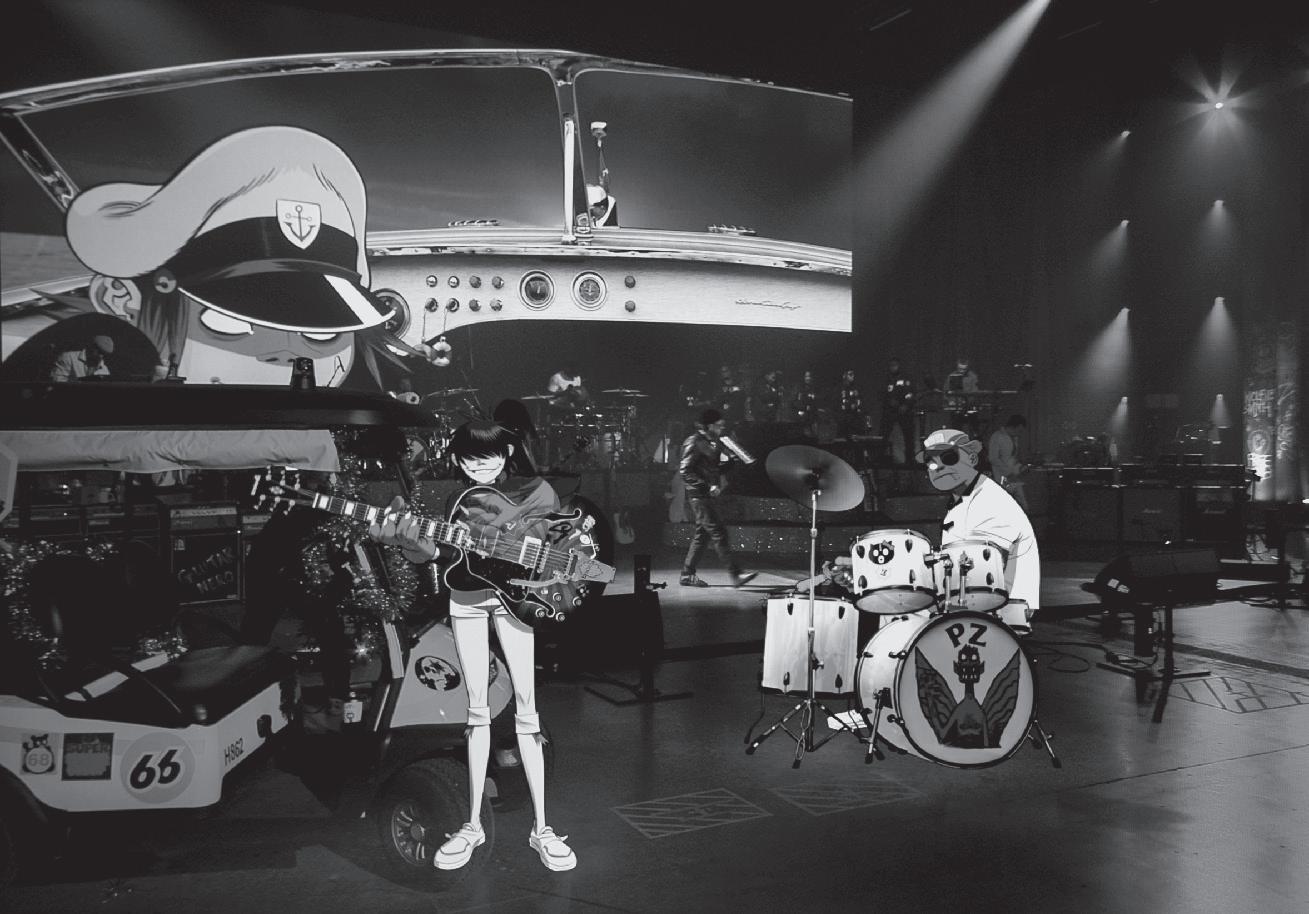

Gorillaz Song Machine Live from Kong 20 December 2020

On entering Kong Studios, the implied location of tonight’s livestream, I was pleasantly reminded of hours spent online in my youth, exploring the virtual sometime-headquarters of Gorillaz, engrossed by the interactivity and playfulness on display. Retrospectively, there is much to admire about how the project presented itself in its earlier years; a canny amalgamation of anarchic visuals, cross-platform world-building and zeitgeist-conquering pop. The sensory overload of it all certainly held the attention of a generation, though the barrage seems somewhat minor in comparison to the now-familiar digital landscape it foreshadowed. I am snapped out of my nostalgic haze by the intriguing sight of none other than Robert Smith, himself coyly channelling the vigour of The Cure’s 1980s heyday. One of many guests to appear in person, his appearance on the opener is a welcome reminder of his unmistakable presence as a vocalist. As the group rattles through the next few tracks, it is clear that the performance is primarily a showcase of the recent album. Alternating between effective-enough prerecorded holograms of the likes of Beck and Schoolboy Q, and more lively cameos from Leee John and Kano, the show strikes a healthy balance not dissimilar to the band’s usual live performances. The focus on the new album certainly emphasises that it is one of their more engaging releases in recent years. Visually, while there’s a smattering of Gorillaz ephemera strewn throughout the set design, and animations of the fictional band implanted intermittently, the focus is clearly on ringleader Damon Albarn and his slew of guest stars. This is at no point clearer than when Slowthai, Slaves and Albarn (inexplicably grinning in novelty pineapple shades) are pogoing around like cider-addled teenagers to the single ‘Momentary Bliss’, the result falling somewhere between infectiously joyous and gratingly irritating. It’s the playfulness of the affair that shines through brightest, and when suddenly a be-robed Matt Berry appears for a rendition of deep cut ‘Fire Coming Out of a Monkey’s Head’ my dormant nostalgia is once again piqued. As the camera weaves round to an intimate acoustic stage, what follows is pure fan service: a run through of old favourites including a rare performance of debut track ‘Dracula’ and the choral finale of sophomore record Demon Days. Finally, as Albarn tinkers on a small synth, recalling the inception of hit single ‘Clint Eastwood’, the camera spins back round to the main stage for a truly animated rendition of the classic UK garage remix featuring MC Sweetie Irie. As the credits roll, I am left with a huge grin across my face. Oskar Jeff

Jerskin Fendrix Cafe Oto, London 20 December 2020

In July of 2020, with live streamed gigs still in a flap somewhere between excitement and terror, Nick Cave did a very Nick Cave thing and proved that it really wasn’t rocket science. For his Idiot Prayer performance, he hired the vast Alexandra Palace and a grand piano, and stripped twenty-two Bad Seeds songs down their essence on the single instrument. Easy for him, though – he’s Nick Cave. But easy for Jerskin Fendrix too, it seems, even if his end-of-year show was a reduced Idiot Prayer from every angle, apart from the man’s talent. We get just 5 songs, in Café Oto rather than a grand palace, with Joscelin Dent-Pooley – a man who does not enjoy playing live with or without an audience – in a red puffer jacket and Yankees cap, not a Saville Row suit. Amazing what Fendrix can do in such a small space of time, though, and even more impressive how far his songs had to travel from ADHD electronic melodramas down to one man and a piano in an empty bar. ‘Onigiri’ had the furthest to go – a pitch-shifted banger of brilliantly dumb drops on debut album Winterreise; here, a rinky dink show tune for its author to casually showboat his classical piano chop over. No longer obscured by layers of beats, drones and indulgent production tricks, just how well Fendrix can play is astonishing. The line in ‘Oh God’ (also performed tonight) says it all – “If only the girls in here could see me play piano” has never made so much sense.

The plaintive chords of ‘I’ll Clean Your Sheet’ looks set to be the festive high point, but then he closes with ‘Ice Cream’; a Christmas collaboration with Black Midi. It doesn’t have the noodling band coda anymore, just Fendrix’s minor keys for a hook of “It’s always Christmas time, when I’m with you”. Naturally, it sounds crushingly sad, even when paired with video images of a young mother playing with her son in the snow. He can do it all, and inside twenty minutes. Stuart Stubbs

Vanishing Twin Presents: Pensiero Magico 21 January 2021

So much of Vanishing Twin’s work seems to exist in its own universe; a timeless, weightless cosmos resembling our own but somehow other. With this in mind, their new live show, titled Pensiero Magico (translated as Magical Thinking) is an intriguing prospect. We’re thrown straight into the action, the band filmed in intimate, homemade style in soft-focus monochrome. As a basic look it complements their heady blend of psych, pop, prog and funk nicely enough, but after a while a few of the details start to grate a little. The screen is filled with polka dots, mannequins, kitschy objets d’art and retrofuturist costuming, all of which is fine on its own, but adds up to a rather hackneyed reworking of the kind of psychedelic whimsy that moth-eaten vintage shops and The Mighty Boosh rinsed the charm out of many years ago now. Of course, some of this goes with the territory – early Pink Floyd, King Crimson and Can all cast significant aural and visual shadows over much of Vanishing Twin’s work, as much as other, more contemporary semi-revivalists like Broadcast and Stereolab – but it does feel a bit tired. But everyone’s options are limited at the moment. Fortunately, the band’s musical performance largely outweighs any aesthetic shortcomings: they inhabit the worlds they create superbly, their playing lithe and reactive. Drummer Valentina Magaletti is particularly impressive, her understated style allowing her to shepherd all manner of subtle flourishes and flavours into each groove. Tracks like ‘Choose Your Own Adventure’ and ‘The Conservation of Energy’ are just beautiful, Cathy Lucas’ vocals beaming out across the mix, perfectly weighted against the shapeshifting instrumentation. ‘Language Is A City (Let Me Out!)’, towards the end of the set, is perhaps the pick of the bunch, heavier and more purposeful than the album version – exactly the kind of human, real-time difference that gives live music its particular magic. It’s exhilarating stuff, tinged with melancholy, and makes me miss gigs all the more. Luke Cartledge These New Puritans XONE.1 4 December 2020