THE BOROUGH MARKET GUIDE TO Shellfish

From scallops and oysters to crab and langoustine, a guide to sourcing and cooking molluscs and crustaceans

From scallops and oysters to crab and langoustine, a guide to sourcing and cooking molluscs and crustaceans

It’s not often that shellfish become front page news, but in recent times they’ve made headlines on several occasions – and not in a good way. As a result of the great Brexit miracle, live bivalves such as oysters, scallops, clams, cockles and mussels can no longer be exported to Europe. With significant delays now locked into the system, EU demand for other shellfish has plummeted too: no seafood benefits from sitting around for long.

This is a problem. Previously, the majority of shellfish landed on British shores was sent abroad – a reflection of the esteem in which our seafood is held on the continent, but also of the relative lack of interest over here. Our islands are blessed with an extraordinary abundance of stunning shellfish, from Dorset scallops and Colchester oysters to Scottish langoustines and Northern Irish razor clams. Now, for the sake of those struggling fishing communities and for our own dining pleasure, we could all do with exploring these culinary treasures a little more than we currently do.

At Borough Market – at Furness Fish Markets, Shellseekers Fish & Game and Richard Haward’s Oysters – you’ll find exceptional British shellfish from sustainable sources. Here, you’ll find everything you need to make the most of it.

Borough Market Online offers a wide selection of our traders’ produce, delivered direct to London addresses and, where available, by post to the rest of the UK.

goodsixty.co.uk/borough-market

Richard Haward

Oysters with Market garnishes

Ed Smith

Oysters & champagne

Lesley Holdship

Deep & meaningful: Diving with Darren Brown

Clare Finney

Scallops with beurre noisette & soft herbs

Jenny Chandler

Ginger, chilli & soy steamed scallops

Ching-He Huang

Shell shock: In praise of the brown crab

Thom Eagle

Crab, asparagus & Jersey royal salad

Rosie Birkett

Langoustine linguine

Nicole Pisani

Paprika pork collar & clams

Ed Smith

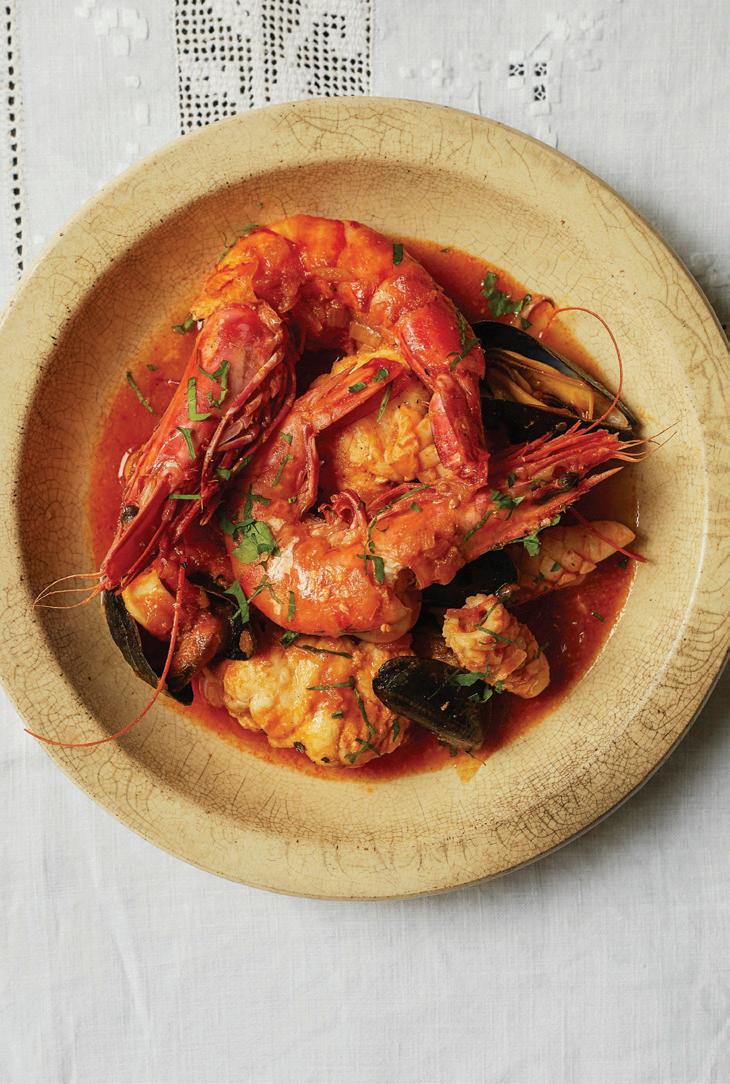

Brodet (Croatian seafood stew)

Dhruv Baker

Razor clams with black bean chilli

Jeremy Pang

Mussels, cheddar, cider, cream, mustard & thyme

Neil Forbes

Razor clams, dulse, guanciale & cider

Paula McIntyre

Richard Haward of Richard Haward’s Oysters is the seventh generation of his family to cultivate oysters in the River Blackwater, on Mersea Island, Essex. He sells the Colchester native oysters that have been harvested from the area’s creeks for thousands of years, as well as hardier Pacific oysters – also known as rock oysters – which were introduced there in the late sixties. Richard doesn’t consider himself an oyster ‘farmer’: “There are some oyster farms that use specially constructed pens and oyster bags, but our oysters live on the river bed, so it would be more accurate to say that we cultivate oysters,” he explains.

The deep waters where the oysters spawn are often not ideal for their further development – the shell grows but they don’t fatten up, so you don’t get much meat. The flesh can be very thin and watery. So, after they’ve reached a certain size we move them to oyster beds situated in creeks that run into the main river. This seems to be the environment that produces the best quality oysters. A lot of what we do is about making sure the oysters are in the right part of the river to thrive. For that, you have to know the river intimately.

Do you treat both species of oyster the same way?

The two are very different. There is an old saying about native oysters: “The first thing they think about is dying.” They don’t like too much heat, cold or silt. The water here is brackish – a mixture of seawater and fresh water – so the salt levels can change. Native oysters struggle if the salt levels fall too

much, so we have to monitor the salinity. We also have to ensure they remain under water all the time. The river is tidal, and if they are left exposed on the foreshore at low tide, a cold snap can kill them. Rock oysters are much hardier and can cope with most changes, but – like all oysters – too much silt is bad for them. Oysters feed by filtering nutrients out of the water that flows over them, and high silt levels can make this difficult.

We bring them up by dredging. We return the ones that are too small to the beds. We separate any that have stuck together, because oysters that have fused together will not develop properly. This is also when we move oysters between locations if we need to, and check for pests. We go out four or five days a week, so we develop a feel for the condition of the beds and we can spot any issues that are developing.

The biggest predator is the starfish. We kill any that are brought up, which sounds harsh, but it is the only effective and responsible way to control their numbers. We also remove any oysters that show signs of ‘oyster drill’ – a snail that bores into the oyster and kills them.

It is important to understand that there are different levels of dredging. We use very light dredgers. These skim across the surface of the seabed and don’t gouge into it in the way that heavier dredgers do. In fact, the way we dredge actually helps to maintain

the riverbed. Recent studies have found that areas that are being worked for oyster cultivation have greater biodiversity than areas that are not. Regular light dredging helps to maintain low silt levels – it stirs the silt up, allowing it to be carried away by the tide – and this helps create a good habitat for other marine life, as well as for oysters.

Do you have to do anything else to maintain the beds?

Not really. The main thing is to stop silt from building up. If we stopped dredging, the silt would build up surprisingly quickly. Other than that, we just leave the river to its own devices.

What happens to the oysters after they’ve been harvested?

They are placed in baskets and covered with wet sacks to keep them cool and damp. When we get ashore we wash and grade them, then the oysters go into depuration tanks to flush out any toxins they might have picked up while feeding. The river water flowing

through these tanks has been placed under intense ultraviolet light, which purifies the water while leaving it rich in nutrients. The oysters are cleaned as they feed.

Another old oysterman saying is: “Treat your oysters like eggs.” They are living creatures, so if you throw them about they will get stressed. Careful handling is so important. Stressed oysters don’t feed properly, making the purification process less effective.

Is there an oyster season?

Not for rock oysters, but we can only sell native oysters from 4th August to 14th May. Natives are still in very short supply. There are regeneration projects aimed at building stocks up, but that will take several years.

Are your oyster beds in good condition at the moment?

Yes, they are. If we are responsible, they should remain so for the eighth generation of Hawards, who are already continuing the tradition of working the oyster beds.

These three simple garnishes utilise striking condiments from around the Market (and will work equally well with either native oysters or rock oysters). Each garnish recipe makes enough for a dozen oysters.

Ingredients

Raspberry vinegar and shallot mignonette:

3 tbsp sweet raspberry vinegar

1 tbsp very finely diced shallot

3-4 grinds of a black pepper mill

Aged balsamic vinaigrette:

1 tbsp aged balsamic vinegar

3 tbsp peppery extra virgin olive oil

½ tsp flaky sea salt

4 chives, finely chopped (optional)

Hot sauce:

Scotch bonnet hot pepper sauce

For the raspberry vinegar and shallot mignonette, combine the ingredients in a small bowl. Add 1 tsp mignonette onto each oyster.

For the aged balsamic vinaigrette, combine the balsamic, olive oil and sea salt in a small bowl. Stir vigorously to emulsify the liquids. Add 1 tsp vinaigrette onto each oyster, and garnish with the chopped chives.

The hot sauce method could not be simpler! Simply add 2-3 drops of hot pepper sauce per oyster.

Richard Haward’s Oysters

Aged balsamic vinegar

The Olive Oil Co

Scotch bonnet hot pepper

sauce

De la Grenade

Ingredients

A knob of good butter

1 shallot, peeled and finely chopped

75ml champagne

100ml double cream

75g fresh spinach leaves

4 oysters

½ lemon

Make your sauce by melting a drop of butter in a large wide sauté pan. Add the shallot and cook gently for 5 mins until tender. Pour in the champers and bubble for around 5 mins to reduce a little, then pour in the cream. Bubble vigorously for another 5 mins to reduce, until silky and thick. Set aside for the time being.

Warm another lump of butter in a pan, adding the spinach leaves. Cover with a lid and cook for 1 min over a medium heat. This should wilt the spinach beautifully. Season.

Shuck the oysters when you are ready to cook them, not before, then set aside for the moment. Rest the deep shells on a bed of salt on a baking sheet. Heat the grill to high.

Fill the shells with the spinach mixture and nestle the oysters on the top. Spoon over the sauce then place under the grill and cook for 3-4 mins until golden, bubbling and hot, hot, hot!

Richard Haward’s Oysters

Champagne Borough Wines

Spinach

Ted’s Veg

“Sometimes it is like looking under your bed for a pair of socks, the visibility’s that poor. If the tide is strong it’s so gloomy, you can end up bumping into things.” Other times, expert scallop diver Darren Brown can spend a full hour and 40 minutes picking what some have likened to solid gold coins off the floor. “It’s a gamble,” he shrugs, checking his watch and putting his foot down, in a van chockful of gadgets and gizmos. Time and tide wait for no man – not even an ex-marine who, when he isn’t diving, is either line fishing or stalking deer and rabbits on Dartmoor; and with a slight kerfuffle over a hole in Darren’s dry-suit this morning (conclusion: it’s fine – “and if it isn’t I’ll know about it soon enough”) the race is on.

We pull up at the docks: the brooding grey arm of the Isle of Portland on one side, the steely grey of Weymouth bay ahead. It’s a formidable looking place, not helped by gloomy skies and the knowledge that, just out of sight on the island, lies one of Britain’s most notorious prisons. Darren’s boat is moored in the old naval base at the foot of the island, “so really I’ve come full circle. This is the base where I served as a marine. It is a bit weird, coming back here,” he acknowledges. “I walked out in 1997.” After 20 years of supplying fish and game to his stall at Borough Market, hunting and fishing have become “a way of life” for him.

“It’s what I do,” he explains, loading a trailer with baskets, his suit and his fins (“Not flippers. Flipper is a dolphin, darling,” he corrects) and setting off to the mooring. Every morning is early, to catch the tide and some scallops or sea bass, and every night a late one, after an evening spent stalking

the moors. Darren’s not complaining. “I have turned my passions and interests into a business,” he says – and it’s a successful one, too, in spite of some serious setbacks.

Of course, scallop fishing isn’t easy – at least, not the way Darren does it. Hand-diving only accounts for two per cent of scallops sold in Britain. Most of the scallops you’ll see in the shops will have been dredged, using what are effectively large metal rakes to scrape scallops – and inevitably, a load of other wildlife – off the seafloor.

“If this was on land, where people could see the havoc they cause, they’d stop it immediately. It’s like the moon down there after they’ve been at it. Everything is upside down, there’s no life at all.” It could take years to grow back, “if it ever does”. But attitudes are slowly changing. Here in Dorset, Darren’s vociferous campaigns against dredging have helped in getting it banned from several areas along the Jurassic Coast.

We board the Maddy Moo: still wet and shining from the deep clean she’s received this morning from Jeff Parish, Darren’s able seaman. “You should have seen her last night,” he grins when we comment on her shipshape appearance “after a seven-hour sea bass fishing trip”. They’d met with limited success on the trip: “Those bloody netters, they scoop them all up,” Jeff complains. Like the dredgers scouring the seabed, the trawler boats are the antithesis of the sustainable, man-versus-fish tactic of rod and line fishing. “You can be the best fisherman in the world, but you can’t catch fish if there aren’t any there to be caught.”

Today, though, Darren is hopeful as we chug gently out of the harbour. On the small black screen in the cabin the outline of the sea bed appears in green squiggles, including a huge naval boat sunk deliberately during the first world war to block the harbour entrance and defend it against German submarines. We slip over it easily, and are released into the grey-green plains of the English Channel. The cliffs are cragged and menacing but, as we come to a stop for Darren to slip into the water, the sea slapping the sides of our little boat is slack and peaceful. We’re at the sweet spot: the gap between tides.

Slip is an understatement. With air cylinders, 32 pounds of weights around his waist and several baskets for collecting scallops, Darren’s entrance into the lolling sea is anything but slow. Even his suit is heavy: a thick, black skin of rubber. On his back, Darren is carrying my entire weight in tank, oxygen and mixed gases. “I’ll be working on 40 per cent oxygen today, which is twice as much oxygen as is in the air. That reduces my exposure to nitrogen which, if it becomes

saturated in your blood and doesn’t have a chance to escape as you come up, gives you the bends. It is amazing isn’t it,” he says, fingering his mouthpiece, “that I am reliant on this little bit of rubber to keep me alive.”

In the pocket of his suit, Darren carries a flare. “I’ve been lost at sea for seven hours before. I’m not letting that happen again,” he says grimly. Tied to his belt are the net bags he will fill with scallops then send to the surface, by attaching them to what is effectively an inflatable balloon. He’ll have an hour, he reckons, before the flood of the tide kicks. “I’ve been doing this since I was a teenager. I could go round after someone less experienced and pick up twice as many as they have done. You get what you call the eye, for scallops.” Even while picking up one unwitting shellfish off the sea floor, Darren has one eye scanning the seabed for his next find. A flicker of movement; the flash of an orange frill; even just a slight indentation in the sand can denote a piece of buried treasure.

While Darren is in the deep, Jeff will be manning the boat, keeping his eyes peeled for the inflatable balloons that denote a fresh bag of scallops, and winching them up onto deck with the aid of a small crane.

“I’m going to jump over here, captain,” Darren shouts, heaving the cylinders onto his back and diving into the water with surprising ease, if not all that much elegance. Jeff heads to the driver’s seat, ready to guide the boat toward his first find. “When the bag comes up I have to judge which way it’s going to float, and be downwind of it. There is no tide at the moment, so it all hangs on the breeze.” One thing you notice when you spend time with seafarers is how much information they can glean from their environment: the look of the sky, the sound of the sea – even the feel of the winds.

Jeff’s been fishing for as long as he can remember, though he has only recently started making a living from it. “I love the buzz of it,” he explains. As we chat, a red balloon appears about 50 metres away from us, and Jeff starts nudging the boat towards it, reading the wind all the while. Lining the crane up with the bobbing balloon is no mean feat. It appears static, but it’s moving rapidly across the surface and Jeff has to make an informed guess on its speed and distance. He leans over, hooks it to the crane and pulls it on board.

It’s overflowing: scallops, some weedy, some barnacled, all beautiful, spill out across the deck of the ship and Jeff starts sifting and sorting. All the scallops must be graded by size before they can be landed: the statutory minimum size for a king scallop is 100mm,

and for a queen it is 40mm. Any smaller than that and they’re to be chucked back into the water, in order that they can continue to grow.

This is the other problem with dredging. Where Jeff and – when he resurfaces –Darren can measure each shell there and then, the dredgers have no such option. While the mesh collector bag attached to the dredge is designed to prevent the collection of undersized scallops, it is inevitable that some get caught up inside. These tiddlers are, eventually, returned to the waters – but there is some doubt over whether they can survive the experience of being dredged.

By this point two more balloons have popped up onto the surface – and not before time. “See that? There is a bit of flood kicking in already. He won’t be long now,” Jeff observes, scanning the surface. Eventually he resurfaces: his face triumphant against the steely grey of the water, and we make our way over to him. “There were absolutely stacks down there!” he puffs as Jeff leans down, seizes him by the back of his suit, and hauls him over the side.

Together, the fishermen gather up the last bag of scallops, and start sorting – largely by sight, but using a ruler to check those they’re unsure of. As the Maddy Moo makes her way back to shore, Jeff continues sorting, sending the undersized scallops flying gaily over the side. “Until next year!” I shout silently, as the little shells soar through the air and plop daintily into the sea, in the boat’s wake. In the meantime, we’ve a market to get to –and, as is tradition after a hard day’s work on the water, a swift half to drink.

IF THIS WAS ON LAND, WHERE PEOPLE COULD SEE THE HAVOC THEY CAUSE, THEY’D STOP DREDGING IMMEDIATELY. IT’S LIKE THE MOON DOWN THERE AFTER THEY’VE BEEN AT IT. THERE’S NO LIFE AT ALL

Scallops are a luxury and very much a special treat, but they’re also a great place to start when encouraging children to try shellfish. They taste beautifully sweet, especially accompanied by the nutty butter. The shells give hours of entertainment too, transformed into objets d’art once carefully decorated with nail varnish.

Ingredients

12 scallops

150g unsalted butter

Juice of ½-1 lemon

A few sprigs of any selection of chervil, dill, parsley and some chives

1 tbsp olive oil

Trim the little piece of firm white muscle from the scallops (found on the opposite side from the coral). Heat the butter in a small pan without stirring, until it froths and then browns. Once it smells sweet, nutty and has bricky-brown speckles you must add the juice of ½ a lemon to stop it burning.

Remove the tender leaves or fronds from the herb stalks and chop the chives. You want about 1 tbsp of herbs in total.

Heat the olive oil in a large frying pan until searing hot and then place the scallops in the hot pan. You will probably have to cook these in two batches, don’t crowd the pan or they will sweat rather than sear. Season with salt and pepper, sear for about 2 mins and then flip over and cook until the sides are just opaque (about 2 mins longer).

Add the herbs to the nutty butter (leaving a few leaves aside as garnish), taste and add salt, pepper and more lemon juice if required. Serve the scallops on warmed plates and spoon over the beurre noisette. Eat right away with a good baguette to soak up the butter.

ALTERNATIVE: Use the caramelised butter with herbs as a sauce for any grilled or fried flat fish. Filleted sole, plaice and dabs are absolute winners with small children. Capers are delicious added to the sauce, too.

Shellseekers Fish & Game

Unsalted butter

Hook & Son

Herbs

Turnips

Ingredients

4 large hand-dived king scallops, in their shells

1 red chilli, seeds removed and chopped

2-inch piece of ginger, grated

1 tsp toasted sesame oil

1 garlic clove, finely chopped

2 tbsp light soy sauce

2 tsp coriander, finely chopped

For the topping:

250ml groundnut oil, for deep frying

2 medium shallots, chopped

6 large garlic cloves, roughly chopped

2 tbsp coriander leaves, shredded to garnish

With a sharp chopping knife, prise open the scallop shells by running the knife on the inside of the shell, releasing the attached membrane.

Pull off the frill, the black stomach sack and any other pieces that are around the meat of the scallop and discard, leaving just the white flesh and any coral. Rinse the scallop thoroughly in cold water – ask your fishmonger to prepare the scallops for you, if you’d prefer.

In a small bowl, combine the chilli, ginger, sesame oil, garlic, soy sauce and coriander. Place the scallops on a heatproof plate, and spoon over one teaspoon of the dressing. Set the plate on a bamboo steamer.

Half-fill a wok with boiling water and rest the bottom of the steamer over the wok, making sure it doesn’t touch the water. Cover with a lid and steam the scallops for 5-6 mins.

While they’re steaming, deep fry the shallots and garlic in hot oil until crisp (it should take less than 1 min). Pour the oil through a sieve, reserving the browned shallots and garlic, and drain on absorbent paper.

Serve the scallops, spoon some of the reserved dressing, and sprinkle over the crispy shallots and garlic. Garnish with fresh coriander leaves.

Shop

Scallops

Shellseekers Fish & Game

Chillies

Stark’s Fruiterers

Shallots

Elsey & Bent

I lived for many years in Norfolk, mainly in Norwich, and particularly there and in the north of the county, all the way from Yarmouth to the Cromer sands, nothing heralds the start of the culinary summer so much as the arrival on the menu and market stalls of crab. In a world where few things still seem to be local and seasonal, where the great herring fisheries have long since moved on and where even Colman’s mustard, until recently the pride of Norwich, has relocated its factories, the Cromer crab is still very much a going concern, available during the season in every cafe and restaurant east of the Wash. Although the people of Cromer are right to be proud of their local crustaceans, really they are good all over the country, if often compared unfavourably with the apparently more glamorous lobster. In defence of the crab, Hugh FearnleyWhittingstall has made the remark that while lobsters cost twice as much as crab, they are not twice as delicious – which is true. Even this misses the point, though, which is that crab is in fact a very different eating experience to lobster, and not really to be compared at all. Bisques and ravioli notwithstanding, the somewhat ephemeral taste of lobster is to my mind best enjoyed as-is, halved and in the shell, with only a flavoured butter of some sort (garlic, usually) to adorn its sweetness – the kind of meal best seasoned by the close proximity of seawater. Crab, it’s true, is often served like this as well. Order a crab salad at, say, Cookie’s Crab Shop on the north Norfolk coast and you will get not a mixed affair but rather a selection of salad items alongside a whole dressed crab – a crab that has been boiled, cracked open, picked over and packed back into the shell.

While nice once in a while, I think this is in general simply too much crab to eat. To me, the strong flavours of both the sweet white meat and the murkier brown really come into their own when combined with other things.

The white meat, from the legs and the fat claws, is essentially the muscle meat of the animal (insofar as a crab can be said to have such a thing), while the brown, composed of not-yet-formed shell and the various organs inside the main body, is crab offal by another name, and the same sort of hierarchy between the two exists as in the meat of any other animals. When I was cooking at Little Duck, lacking the time and the space to really get to grips with a crab, we would buy tubs of either white or brown meat, the former being more than three times as expensive.

As, again, with the cheaper cuts of meat, this distinction is a blessing for those who like deeper flavours; less sweet and delicate, the brinier brown meat is doubly economical, as a little goes quite a long way. Just a tablespoon or two, loosened with a splash of the cooking water, seasoned with some garlic and chilli just-tempered in oil and brightened with a squeeze of lemon juice, makes a wonderful sauce for thick spaghetti; or stir the same amount through a risotto with fresh peas for something that feels like a Venetian spring. The classic treatment, of course, is just to mix it through some mayonnaise and spread it on toast.

Even the less pungent white meat can be happily stretched further with a little thought. A good option is to pair it with something similar in texture, sweetness, or both. At The

Sportsman in Kent, Stephen Harris serves white crab meat with hollandaise sauce and a little shredded carrot, the texture of which exactly matches the just-cooked crab. Eating this was the first time crab really made sense to me, its flavour distinct and exact.

At the restaurant, we used to make a sort of crab soup with sweetcorn and fideos, the little lengths of angel-hair pasta. With brown meat as well as the white stirred through, it was hard to tell what was pasta and what was crab, and the result was a very satisfying plateful. More recently I have cooked firm green courgettes with red spring onions and a little garlic in olive oil and their own juices, sweated together until bright and glossy, but with a good bite still to them, and then mixed the result with mint, white crab meat, and sliced lemons preserved under oil, sweet and green and sunny.

These, like the neatly dressed shells sold by the fishmonger, are all very convenient things to do with a crab, but sometimes convenience is not what you are after. Sometimes (not

often enough), lunch is something that takes a very long time, and results in a great deal of mess. If you find that this is to be the case, then absolutely the best thing you can do is to get yourself a few bottles of riesling and some whole crabs – one of each between two should be enough, at lunchtime – and make a day of it.

Any good fishmonger or market stall, including those at Borough, will be able to supply you with whole crabs. In some cases, if you are adventurous, you might get them live, from which state they will need, for kindness’s sake, to be swiftly despatched, and then to be just as swiftly cooked. Once dead, crab does not like to hang around. I won’t, in any case, go into the details here – you can look up the process elsewhere, if you feel up to it. Whether you buy your crabs alive or cooked, however, you will need the same accompaniments. Crab-crackers and picks if you have them, a couple of hammers and a pack of skewers if you don’t; a bowl of mayonnaise, another of lemon halves, and your best friends. You can clean up tomorrow.

THE BEST THING YOU CAN DO IS TO GET YOURSELF A FEW BOTTLES OF RIESLING AND SOME WHOLE CRABS – ONE OF EACH BETWEEN TWO SHOULD BE ENOUGH, AT LUNCHTIME – AND MAKE A DAY OF IT

Crab, asparagus and Jersey royal potatoes are, for me, the holy trinity of late spring and early summer produce – each a special treat in its own right, but all great friends when prepared together too.

300g Jersey royal potatoes, scrubbed

1 sprig of mint

300g crab meat, split into white and brown

1 green apple, cored and finely chopped

3 spring onions, finely sliced

200g asparagus, woody stalks removed and saved

1 baby gem, leaves picked and washed and dried, heart split in half

10g chervil leaves, washed and picked

10g tarragon leaves, washed and picked

10g parsley leaves, washed and picked

20g seaweed or sea purslane

Juice of 1 lemon

For the mayonnaise:

2 egg yolks

½ tsp sea salt

Juice of ½ lemon

200ml vegetable oil

100ml extra virgin rapeseed oil

Pinch of cayenne pepper

Pinch of white pepper

First cook the potatoes. Bring a large pan of salted water to boil, add the mint and the Jersey royals and simmer for 15 mins, until tender – do not be afraid of overcooking them, as they are far better soft than chalky.

While the potatoes cook, make the mayonnaise. In a large bowl, whisk the egg yolks, salt and lemon juice and then, still whisking, gradually add the vegetable oil in a steady stream. Continue to whisk until a mayonnaise consistency emerges. If it splits, don’t panic – just add a squeeze more lemon and keep whisking vigorously until it comes together. Add the rapeseed oil, whisking, to finish the mayo, then add the pepper. Check for seasoning, adding more salt or lemon as required.

In another bowl, mix half of the mayo with the brown crab meat, a squeeze more lemon and cayenne pepper. Fold the apple and spring onion through this. Taste for seasoning.

Boil the asparagus stalks hard in a pan of water for 10 mins to make a quick stock, then chop the spears into three on the diagonal and boil in the stock for 3-5 mins, until just tender. For the last minute, drop in the seaweed to blanch. Drain immediately and refresh in cold water.

Spread the brown crab meat and apple mayo out on a platter. Top with the potatoes, lettuce, seaweed and asparagus, building up layers and seasoning as you go with salt, pepper and lemon. Top with the remaining mayo, followed by the white crab meat and soft herbs. Squeeze over a touch more lemon and dust with cayenne pepper.

Jersey royals

Turnips

Crab

Shellseekers Fish & Game

Seaweed

Wild Beef

Scottish langoustines are equally delicious boiled or grilled. In this recipe, I simply boil them until just cooked, peel carefully to keep as much of the meat as possible, and then use the pile of shells to make a deep, flavourful bisque sauce for the fresh linguine.

Monk’s beard is similar to samphire, and is grown only for about five weeks of the year in Tuscany. When very young you can use it raw in salads, or lightly steam and dress with a little extra virgin olive oil and lemon juice.

800g raw Scottish langoustines

1 tbsp unsalted butter

1 small onion, roughly chopped

½ fennel bulb, roughly chopped

1 celery stalk, chopped

½ thumb sized piece of ginger, roughly sliced

A pinch of chilli flakes

1 tsp peppercorns (pink or black)

200ml Pernod

500ml fish stock, hot

1 tin coconut paste

500g fresh linguine

80g monk’s beard or samphire

Extra virgin olive oil

Lemon juice

3 spring onions, finely sliced

Bring a large pan of water, along with 2 heaped tsp sea salt, to the boil. Add the langoustines and boil for 2-3 mins, until the flesh is no longer translucent. You may need to boil them in batches, as it’s important not to crowd the pot.

Drain the langoustines and when cool to touch, remove the heads and squeeze the shell so that you can easily peel them. Chill the peeled langoustines and keep the heads and shells to make a bisque sauce.

Melt the butter in a large saucepan over a medium heat and soften the onions, celery and fennel for a few mins before adding the ginger, chilli flakes, peppercorns and then the langoustine heads and shells.

After 1 min or so, deglaze the pan with the Pernod before adding the hot fish stock. Bring back to the boil and then lower to a gentle simmer for about 1 hour, until the liquid has reduced by half, removing any impurities that come to the surface with a slotted spoon. Stir in the coconut paste, and taste for seasoning.

Bring another pan of water to the boil and add the linguine, give a stir and reduce the heat a little to a good simmer until cooked, usually 5-6 mins. Drain and return to the pan.

Steam the monk’s beard or samphire until tender, then add a little extra virgin olive oil and a squeeze of lemon.

Stir the langoustine sauce into the pasta until evenly coated. Add the peeled langoustines and monk’s beard and gently stir through before serving in bowls. Top the pasta with plenty of spring onion.

Langoustine

Furness Fish Markets

Samphire

Fitz Fine Foods

Fresh linguine

La Tua Pasta

This is my take on carne de porco à Alentejana: pork meat, Alentejan style. Once the pork has been brined, it’s easy, quick and very effective. I also think it’s a great example of how paprika can act as a key flavouring in a dish – somehow sitting both on the front of the tongue, and in the background behind the pork, clams and wine too.

Sides can be simple because the flavours are bold and the sauce intense. I’d serve this with some plain, boiled waxy potatoes and sautéed kale, cavolo nero, spinach or chard. Or go totally basic, and just have some doughy bread on hand to mop up the juices.

2 x 200-250g pork collar steaks (about 2-3cm thick)

For the brine:

300g water

15g light brown sugar

15g sea salt

1 heaped tsp sweet paprika

The peel of 1 lemon

8 sprigs thyme

For the clams:

400-500g palourde clams, purged in cold water for 15 mins

15 sprigs of parsley

1 romano pepper, finely diced

1 large clove garlic, finely sliced

15g butter

200ml Portuguese white wine

2 tsp sweet paprika

1 lemon, juiced

Make a brine solution by dissolving the sugar, salt and paprika into 300g warm water. Allow that to cool completely.

Put the pork steaks into a ziplock bag or a snug plastic container. Pour in the brine, add the lemon peel and thyme and seal. Place in the fridge for 10-12 hours, then, when the time is up, pour the brine away and discard the thyme and lemon. Place the steaks on a plate uncovered in the fridge for a few hours to dry.

Cut 4cm or so from the end of each parsley stalk and chop very finely, leaving the main part and leaf intact.

Place a heavy-bottomed frying pan on a medium-high hob. Heat 2 tbsp vegetable oil for 30 secs before placing the steaks in the pan. Cook for 2 mins, then flip and cook for 2 mins more. Turn again and add the butter. Cook for a further 45-60 secs on each side, then rest the steaks on a warm plate for 5 mins while you cook the clams.

Add the pepper, chopped parsley stalks and garlic to the still-hot but now empty pork pan (don’t clean out the juices). Soften for 30 secs, then add the clams and shuffle the pan. After 30 secs, pour in the white wine, add the paprika and shuffle the pan again. Place a lid over the top. Cook at a medium heat for 2-3 mins; the clams are done when they’re fully open.

Remove from the heat, take off the lid and add the lemon juice, parsley sprigs and a good pinch of salt and pepper. Stir well and allow the parsley to wilt.

Cut the pork steaks into thick slices and divide between bowls or deep plates. Spoon the clams, parsley and lots of juices over the top.

Pork collar

Ginger Pig

Paprika

Brindisa

Palourde clams

Furness Fish Markets

Ingredients

2 white onions, finely diced

3 cloves of garlic, crushed

450g tin of tomatoes

150ml white wine

20ml white wine vinegar

400g firm white fish (hake or monkfish for instance), cut into 70-75g pieces

12 large raw prawns, head and tail on, shell removed from half and the other half left with the shell on

2 medium squid, cleaned and cut into rings (your fishmonger will be able to do this)

250g live mussels, rinsed and beards removed

600ml fish stock

1 bunch of fresh parsley, finely chopped

1 lemon cut into wedges, to serve

Heat 4 tbsp olive oil in a large, deep frying pan, add the onions and garlic and cook for 10-12 mins, until the onions are translucent but not starting to colour. Add the wine and vinegar and reduce by two thirds. Add the tomatoes and allow to reduce for a further 10 mins.

Carefully lay the fish fillets and prawns into the pan and pour over the stock, carefully shaking the pan to mix through. Cook for 5-6 mins, then add the squid and mussels, cover and cook for a further 5 mins.

Remove the lid, season with salt and pepper, scatter over the parsley and serve along with a wedge of lemon. This is traditionally served with creamy polenta, but is equally delicious with crusty bread.

Hake

Furness Fish Markets

Tinned tomatoes

Gastronomica

Squid

Shellseekers Fish & Game

From Hong Kong Diner by Jeremy Pang

Ingredients

2 cloves of garlic

½ thumb-size piece of ginger

2 tsp preserved fermented black beans

12 fresh razor clams or 500g fresh mussels

1 spring onion, finely chopped

1 fresh red chilli, finely chopped

Vegetable oil, for frying

Fresh coriander leaves, to garnish

For the sauce:

1 tbsp light soy sauce

½ tbsp oyster sauce

½ tbsp hoisin sauce

1 tbsp Shaoxing rice wine

100ml chicken stock

1 tsp sugar

Finely chop the garlic and ginger, then put into a mortar or food processor. Wash the fermented black beans and add them to the mortar or food processor and crush together to form a paste. Combine all the sauce ingredients in a small bowl or ramekin.

Soak the razor clams in salted cold water for 10 mins, then blanch in boiling hot water for 1 min. Once they have cooled enough to be handled, they need to be cleaned – much like mussels, there is a ‘beard’ of sorts that can be quite dirty. The clams should have opened up from the blanching process, and you will now see the white meat, with a slightly dark part attached. Pull apart and discard the dark, sandy part of the clam until you are left with just the white meaty parts, while continuing to clean each shell under the running cold tap. Once the clams have been cleaned thoroughly, place them in a bowl of cold water once more.

Bring 1 tbsp vegetable oil to a high heat in a wok and swirl it round with a ladle or spatula. Once smoking hot, add the spring onion and stir-fry for 30 secs. Next, add the black bean paste and fry for a further 10-20 secs.

Add 1 tsp vegetable oil to the wok and allow it to smoke. Add the chilli, stir-fry continuously for 10 secs, then pour in the sauce. Bring to a vigorous boil, then add the clams, folding the sauce evenly through them, and cover with a lid. Steam with the lid on for 1 min, then remove the lid and fold everything together once more for a final 1-2 mins, to make sure it’s all evenly coated and seasoned.

Serve immediately, garnished with the coriander leaves and a few of the blanched razor clam shells.

Razor clams

Furness Fish Markets

Ginger Turnips

Chicken stock

Northfield Farm

Ingredients

300g mussels, cleaned and beards removed

A sliver of garlic

25ml cider

A few sprigs of thyme

1 tbsp grain mustard

½ good eating apple, diced, skin on

75ml double cream

50g cheddar, grated

Add the mussels, garlic, cider and thyme to a large, hot pot on the stove and cover with a lid. After 1 min add the mustard, apple and cream, and cook for a few mins until the cream is coming to the boil.

Just before serving add the cheddar and give the mussels a good stir and a final season –it may need a dash more cider, mustard or cream. Serve at once in warmed bowls.

Mussels

Shellseekers Fish & Game

Cider

The Cider House

Cheddar

Heritage Cheese

Ingredients

12 razor clams

4 rashers of guanciale

1 shallot, finely chopped

150ml dry cider

2 tbsp double cream

75g butter

1 tbsp dulse seaweed, chopped

Micro celery, to garnish

Remove the meat from the razor clams –it should come away with the gentlest of prompting – and trim them so you only have the white flesh. Keep the shells for the presentation of the finished dish.

Cook the guanciale in a dry frying pan until crisp. Drain on kitchen paper then chop. Add the shallot to the hot rendered fat. Cook until golden, then add the cider. Bring to the boil and add the clams. Cover with a lid and cook for 1 min.

Remove the clam meat and chop. Boil the remaining juices to reduce by half, then add the cream. Whisk in the butter a little at a time, until incorporated. Check the seasoning, then mix in the clam meat.

Spoon the clam meat into the shells. Dot the guanciale and dulse on top and garnish with micro celery.

ALTERNATIVE: Nori or wakame could be used here instead of the dulse. Pancetta would be a good substitute for the guanciale.

Razor clams

Furness Fish Markets

Guanciale

The Parma Ham and Mozzarella Stand

Double cream

Hook & Son

A SERIES OF MONTHLY PODCASTS FEATURING INTERVIEWS WITH FOOD EXPERTS AND THOUGHT LEADERS FROM BOROUGH AND BEYOND, HOSTED BY ANGELA CLUTTON