Vol.11 Spring 2011

Special Section

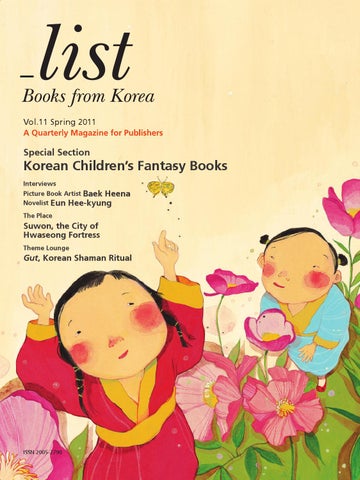

Korean Children’s Fantasy Books Interviews Picture Book Artist Baek Heena Novelist Eun Hee-kyung The Place

Suwon, the City of Hwaseong Fortress Theme Lounge

Gut, Korean Shaman Ritual

ISSN 2005-2790

FAQ What is list_Books from Korea, and where can I find it? list is a quarterly magazine packed with information about Korean books. Register online at www.list.or.kr to receive a free subscription.

Can I get it in English? The printed edition of list is available in English and Chinese. The webzine (www.list.or.kr) is available in English, Chinese, and Korean.

What if I want information about Korean books more often? We offer a bi-weekly online newsletter. Simply email list_korea @ klti.or.kr to begin receiving your free copy.

Who publishes list_Books from Korea? list is published by the Korea Literature Translation Institute, which is affiliated with the Korean Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism. LTI Korea’s mission is to contribute to global culture by expanding Korean literature and culture abroad. Visit www.klti.or.kr to learn about our many translation, publication, cultural exchange, and education programs. Contact : list_korea @ klti.or.kr

Foreword

“You have to see even what you can’t see.” There is a place called Goseong Unification Observatory near the demilitarized zone in South Korea. With a diverse amount of information about the division of Korea on display, it allows us to peer into North Korea, which we cannot visit. Through the telescopes that operate on 500 won coins, you can take an even closer look at the North Korean landscape. During my visit there on a cloudy evening, I overheard a conversation between a young child and his mother. He was nagging his mother to let him look through the telescope. She scolded him, telling him he would only be wasting money since he would not be able to see anything anyway. Then the child declared authoritatively, “You have to see even what you can’t see.” The child is right. What I want to discuss now is fantasy. Fantasy is making visible the invisible. It requires the curiosity and ability to see the invisible, and children are readily capable of doing so. Adults give no thought to the invisible, which they cannot think of any reason or need to see. Children, however, are different. They believe that certain things are invisible and yearn to see them, assuming that the invisible can be seen; they therefore also invent invisible things. This is what constitutes imagination and creativity. It is the most fundamental basis and ultimate goal of literature. Herein lies the importance of children’s literature, especially the value of fantasy as a literary genre. The young child’s insistence on seeing the invisible that I mentioned above struck me as very meaningful. On the one hand, it captures the basic spirit of fantasy; and on the other hand, it seemed like the teaching of a sage on how to overcome the division of the country. The message I heard was: We should sustain our efforts to see North Korea, tightly sealed off and invisible, using our curiosity, imagination, and devotion. For people around the world, the first image that comes to mind when they think of Korea is that of a divided country. There is so much that is out of sight, hidden behind this image. One such example is children’s literature. The fact that children’s literature in Korea has seen many remarkable writers and books during its century long history is unknown to most people. In this issue of list, we introduce children’s fantasy books from Korea. The magazine surveys the basic fantasies of Koreans through books that contain Korean myths, legends, and folktales. This will serve as an introduction to the reception of Western fantasies in Korea as well as uniquely Korean fantasies, and into the imaginative games that unfold in some lovely picture books. I hope you will also see the diverse imagination and curiosity with which Korean children’s book writers have been making visible the invisible. By Kim Inae

Copyright © Kim Dong-sung, Jumong, the Heroic Founder of Goguryeo, Woongjin Think Big Co., Ltd.

list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

1

2011 KLTI U.S.Forum The 3rd Korea Literature Translation Institute U.S. Forum (KLTI U.S. Forum) will be held from April 27th through May 2nd in Los Angeles and Berkeley. In Los Angeles, the 2011 KLTI U.S. Forum will feature three themes through a series of three events: “Korean Society in Korean Literature,” “Korean Literature and Film,” and “Korean Authors vs. Korean American Authors” for the period of April 27-29. Some of the participating Korean authors will be available to meet audiences at UC Berkeley on May 2nd.

Forum 1 “Looking to Prosperity from Within the Ruins: Korea in Korean Literature” Date & Place: Wednesday, April 27th at UCLA In a panel discussion with scholars from UCLA, Korean authors Kim Joo-young and Choe Yun will discuss how Korea overcame past hardships and grew into a country that has now hosted the G-20, and how this past is being interpreted in their works.

KLTI Overseas Publication Grants Applicant Qualifications - Any publisher who has signed contracts for the publication rights of a Korean book and can publish the book by December 2011 (The book should be published by then.) - Or any publishers who have already published a translated Korean book in year 2011 based on the contracts for the publication rights of a Korean book

Grant Amount - Part of the total publication expenses - The amount varies depending on the publication cost and genre of the book - The grant will be awarded after publication

How to apply - Register as a member on the website (www.klti.or.kr) and complete the online application form

Application documents

“Korean Literature and Cinema in a Time of Globalization” Date & Place: Thursday, April 28th at the Korean Cultural Center in Los Angeles A Korean literary critic and an American film specialist will talk about Korean movies that have been adapted for the screen from their original texts. Three popular Korean movies will be screened, one each evening, starting Wednesday, April 27th.

1. Publisher’s profile, including its history and major achievements (e.g., its previous publications related to Korea (if any), the total number of books it has published so far, etc.) 2. Publication plan including the dates and budget for translation and publication in detail 3. A copy of the contract between the publisher and the translator 4. A copy of the contract between the publisher and the copyright holder 5. The translator’s resume

Forum 3

Application Schedule

“Korean Writers vs. Korean American Writers” Date & Place: Friday, April 29th at USC Korean writers including Choe Yun and Korean American writers including Leonard Chang will discuss and read excerpts from their work.

Submission period: 2011. 1. 1 ~ 2011. 9. 30 Grant notification: April, July, and October

Forum 2

The program is subject to change. For updated information, please contact Ms. Yoonie Lee at yoonie@klti.or.kr

Contact Name: Jiyoung Ko Email: grants@klti.or.kr

Contents Spring 2011 Vol. 11 01 06 07 08 10

Foreword Trade Report News from LTI Korea Bestsellers Publishing Trends

Special Section

Korean Children's Fantasy Books

12 Mining Tradition, Forging New Enclaves 15 Tapping into Mythology, Legends, and Folklore 18 Animal Fantasy Fiction Dives into a New Decade 21 Child's Play Gets In Touch With Reality

Interviews

24 Picture Book Artist Baek Heena 30 Novelist Eun Hee-kyung

Excerpts

28 The Moon Sorbet by Baek Heena 34 Let Boys Cry by Eun Hee-kyung

Overseas Angle

38 41 42

A Literary Dialogue with Korean novelist Yi In-seong and Chinese poet Yan Li MerwinAsia Emerges on the Translation Scene Introducing Professor Chung Moon-gil, Founder of Contemporary Marxist Studies in Korea

36 Book Lover's Angle: Jean Bellemin-NoĂŤl 75 Writer's Note: Moon Chung-hee

The Place

44 Suwon, the City of Hwaseong Fortress

Theme Lounge

48 Gut, Korean Shaman Ritual

Reviews

52 Fiction 70 Nonfiction 76 Children's Books

Spotlight on Fiction

57 A Dance with Grandma by Oh Chae Illustration by Oh Seung-min

Steady Sellers

69 The Poet 81 Into the Orchard!

Meet the Publishers

82 Gilbut Children Publishing Co., Ltd.

New Books

84 Recommended by Publishers 90 Index 92 Afterword

list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

3

Contributors Antonio J. Doménech del Río is Director of the Korean Program at the University of Málaga. He has translated such works as Yulgok’s Compendio Básico de Educación Confuciana en la Corea del Siglo XVI, Kim Yolgyu’s 15 Códigos de la Cultura Coreana and Gyeongju Namsan, Esculturas Budistas en la Tierra Pura del Reino Coreano de Silla by Kim Wonryong and Kang Woobang. Bae No-pil is a reporter with the

JoongAng Ilbo and a nonfiction writer for the online newsletter plus list_Books from Korea.

Cho Eunsook is a professor of Korean Education at Chuncheon National University of Education and a critic of children’s literature. Her published works include The Formation of Korean Children's Literature. She is also an editor of the quarterly Changbi Children.

Jeong Sooja is a poet of Korean sijo.

Pyo Jeonghun is a book reviewer,

columnist, translator, and freelance writer. He has translated 10 books into Korean and written Books Have Their Own Destiny, A Short Introduction to Chinese Philosophy, and An Interview with My Teacher: What Is Philosophy?

Yu Gina is a film critic and professor

She has written many works including The Empty Well and is the recipient of the JoongAng Sijo Award. She is currently working on a book about the history, life, and culture of Suwon and Gyeonggi-do (province).

Kang Yu-jung is a literary critic.

Pyun Hye-young has published the

Zhang Yibing is vice-president of

In 2 0 0 7 , s h e p u b l i s h e d Oe d i p u s’ Forest. Currently, she teaches at Korea University and is a member of the literature editorial committee for the quarterly publication Segyeui Munhak.

Kim Inae is a children’s writer, critic,

and translator. Among her works are The Cat with Two Feet and Across the River Tumen and Yalu. She is on the editorial board of list_Books from Korea.

Kim Ji-eun is a writer of children’s

Cho Yeon-jung is a literary critic. She made her debut in 2006 winning the Seoul Shinmun New Critic’s Award.

stories and a critic of children’s literature. She currently lectures on theories of writing fiction for children in the Department of Creative Writing at Hanshin University.

Choi Jae-bong is a reporter on

Kim Yeran is a professor of media art

the Culture Desk of The Hankyoreh newspaper.

Choi Yoon-jung is a critic of children’s

literature and director of Baram Books, a publishing company specializing in children’s and young adult’s books. She graduated from Yonsei University in French literature, and earned her MA at the University of Strasbourg and postgraduate DEA degree at the University of Paris. Her written works include the Sad Giant; she has translated over 100 works including L’oeil du Loup.

Doug Merwin is the founding editor

of East Gate Books imprint at M.E. Sharpe, which has published numerous books related to Asia for many years. He has published such works as the Korean Cultural and Arts Foundation Literature Translation Award-winning Peace Under Heaven, My Very Last Possession and Other Stories, a collection that received glowing praise from The New York Times, and the winner of the 2002 Daesan Prize for Outstanding Literary Translation for Everlasting Empire.

Eom Hye-suk is a researcher in

children’s literature and a critic of illustrated books. She also works as a translator. Her major written work is Reading My Delightful Illustrated Books.

Han Mihwa writes on the subject of

publishing. Her written works include Bestsellers of Our Time and This Is How Bestsellers Are Made, Vols. 1, 2.

Jang Sungkyu is a literary critic. He currently lectures at Kwangwoon University.

4 list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

short story collections Aoi Garden and To the Cages and the novel Ashes and Red. She won the Hanguk Ilbo Literature Award in 2007 and the Lee Hyo-seok Literary Award in 2007. She is on the editorial board of list_Books from Korea.

Richard Hong is a book columnist and the head of BC Agency. He translated 13: The Stor y of the World’s Most Notorious Superstitions, appeared on KBS 1 Radio’s “Global Today,” and writes columns for The Korea Economic Daily and Posco News.

Rosa Han is an editor of foreign

at Kwangwoon University and on the editorial board of list_Books from Korea.

literature at Yolimwon Publishing Co., where she also manages overseas sales of Bluebird Publishing Co. She is the CEO of Toc Publishing Co., a publishing house specializing in YA and children’s fiction and nonfiction.

Kwak Aram is a reporter at the Culture

Shin Hye-eun is a full-time lecturer

Department of the Chosun Ilbo. Her series introducing masterpieces of art, “The Masterpiece Files by Kwak Aram,” was serialized in Chosun Ilbo’s weekend supplement “Why” in the first half of 2008. Her works include Said the Picture to Her: Working Women in Their Thirties and When I Have to Wait, I Read.

Lee Jaebok is a children’s literary

critic. He is the author of such works as Children Gobble Stories.

Lee Jiyoo is a science writer and a writer

and translator of children’s literature. Her works include Mrs. Shooting Star’s Space Tales, Volcanoes, Star Shooters, and many more. She is an editor of the quarterly Changbi Children.

Oh Yunhyun writes children’s books.

Currently, he is editor-in-chief of the culture and science section of SisaIN, a weekly magazine, and is a member of the World of Children’s Story Society. His books include Tori Is Escaping from Game Land and The Amazing Mystery of Our Body.

Park Sungchang is a literary critic and

professor of Korean literature at Seoul National University. His works include Rhetoric, Korean Literature in the Glocal Age, and Challenges in Comparative Literature. He is on the editorial board of list_Books from Korea.

of primary education at Soong Eui Women’s College.

Shin Junebong is a journalist at the

Culture Desk of the JoongAng Ilbo. He received his MA from Goldmiths, University of London in 2008, and is interested in theoretical analyses of literature, cultural phenomena, and customs.

Shin Soojeong is a literary critic. She is

currently a professor in the Department o f C r e a t i v e Wr i t i n g a t My o n g j i University, and is also a member of the editorial committee for the quarterly publication Munhakdongne. Her written works include the critical anthologies Meat Hanging in the Butcher’s Shop and How Do We See the Literature of the 1990s? (co-author).

Wang Yanli received an MA in Korean

Studies at Inha University and is preparing a doctoral dissertation at the same university.

Yi Soo-hyung is a literary critic and a

senior researcher at the Seoul National University Academic Writing Lab. He studied contemporary literature, and has taught at Hongik University, Seoul Institute of the Arts, and Korea National University of Arts.

of film and digital media at Dongguk University. Her works include Yu Gina’s Women’s Cine-Promenade and Find Yourself Through Film (co-authored with Im Kwon-taek). She is on the editorial board of list_Books from Korea. Nanjing University and one of the foremost Marxist scholars of China. He has published such works as Back to Marx: The Philosophical Discourse in the Context of Economics, The Impossible Truth of Being: Imago of Lacanian Philosophy, and Back to Lenin-A Posttextological Reading on Philosophical Notes.

Translators Ann Isaac has a BA and MA in Classics

and English Literature from Cambridge University, and an MA in Japanese Studies specializing in translation from the University of Sheffield. After moving to Korea in 2001, she studied Korean at various institutions and currently translates from Korean to English, with a special interest in literary translation.

Cho Yoonna studied English literature

at Yonsei University and earned her MA in conference interpretation at the Graduate School of Interpretation and Translation at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies. She is a freelance interpreter and translator.

C h o i In yo u n g i s a n a r t i s t a n d

translator. She has been translating for over 20 years. She specializes in Korean literature and the arts.

Christopher Dykas studied German

Studies and Politics at Oberlin College. After a journey through language that brought him to learn French, Spanish, and Korean, he now resides in Seoul where he works as a freelance translator and broadcaster.

H . Ja m i e C h a n g r e c e i v e d h e r undergraduate degree from Tufts University. She is a Bostonian/Busanian freelance translator.

Jaewon E. Chung is working on

several translation projects under the guidance and suppor t of the International Communication Foundation and LTI Korea. For his translation of Hwang Jung-eun’s “The Door,” Chung received the 38th Korea Times Modern Literature Translation Commendation Award.

Julie Min is a Korean-Canadian who

studied English Literature at University of British Columbia. She has translated several Korean short stories and children's books into English.

Yi Jeong-hyeon is a freelance translator.

She has translated several books and papers on Korean Studies including Korean Traditional Landscape Architecture (2007), and Atlas of Korean History (2008).

Jung Yewon studied interpretation and

translation at GSIT, Hankuk University of Foreign Studies. Jung has worked for Bain & Company, Korea and various other organizations, and is currently working as a freelance interpreter/translator. Jung received the Daesan Foundation Translation Grant in 2009. She is currently working on No One Writes Back, a novel by Jang Eunjin.

Kari Schenk was the co-recipient of the

commendation award in the 2006 Korea Times contest for new translators, and in 2010 she attended a special course in translation at LTI Korea. Her graduate studies in English Literature and Applied Linguistics have been of assistance to her during the seven years she has spent lecturing in English at Korea University.

Kim Hee-young is a freelance translator.

She is currently working on the translation of a collection of the experiences of comfort women titled Histories Behind History.

Kim Ungsan graduated in German

Literature from Seoul National University and also studied at the Free University of Berlin. He earned an MA degree in Comparative Literature. And currently, he is working on a PhD in English Literature.

Park Jinna is a freelance translator based

in Seoul with a special interest in education and environmental issues.

Park Sang-yon is a PhD candidate in

Editors Kim Stoker earned a MA in Asian Studies

Vol.11 Spring 2011 A Quarterly Magazine for Publishers

PUBLISHER _ Kim Joo-youn

at the University of Hawaii. She is currently a full-time lecturer at Duksung Women’s University.

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR _ Kim Yoonjin

Krys Lee is an editor, translator, and fiction

EDITORIAL BOARD Kim Inae Kim Yeran Park Sungchang Pyun Hye-young Yu Gina

writer. Her short story collection will be published by Viking/Penguin in the U.S.A. and Faber and Faber in the U.K., in 2012.

Cover Art Choi Jung-in studied printmaking at

Hongik University. She also illustrated Princess Bari, Gyun-woo and Jick-nyo, and Magic Red Lipstick.

MANAGING DIRECTOR _ Lee Jung-keun

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Kim Sun-hye MANAGING EDITORS Cha Youngju Kong Min-sung EDITORS Kim Stoker Krys Lee ART DIRECTOR Choi Woonglim DESIGNERS Kim Mijin Lee Jaehyun Jang Hyeju

Social Anthropology at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. She is currently helping North Korean refugees settle in the UK. She has translated a number of books and papers on Korean Studies including Suwon Hwaseong: The New City of the Joseon Dynasty Built on the Spirit of Practical Learning.

PHOTOGRAPHER Lee Kwa-yong

Peter J. Koh is a freelance translator/

All correspondences should be addressed to the Korea Literature Translation Institute at 108-5 Samseong-dong, Gangnam-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea 135-873 Telephone: 82-2-6919-7700 Fax: 82-2-3448-4247 E-mail: list_korea@klti.or.kr www.klti.or.kr www.list.or.kr

interpreter. He is currently participating in KLTI’s 2010 Intensive Workshop in Literary Translation.

Sue Y. Kim received her BA in English

Literature and International Studies from Ewha Womans University. She currently resides in Los Angeles, and is working on a novel in the Creative Writing program at the University of Southern California.

Yang Sung-jin is currently a staff reporter

at The Korea Herald, covering new media and books. Yang wrote a Korean history book in English titled Click into the Hermit Kingdom and a news-based English vocabulary book, News English Power Dictionary. He runs a homepage at web. me.com/sungjin.

PRINTED IN _ EAP

list_ Books from Korea is a quarterly magazine published by the Korea Literature Translation Institute.

Copyright © 2011 by Korea Literature Translation Institute ISSN 2005-2790

Cover art © Choi Jung-in

list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

5

Trade Report

Korean Children’s Books Make Inroads in France

Notably, French publishers’ keen attention to Korean books is helping Korean publishers think beyond the domestic market in a way that broadens their perspective and pushes them to publish more diverse children’s books for overseas markets. By Rosa Han

2

1

Korea n children’s picture books began to gain public a t t e nt i o n o n t h e Fr e n c h market in 2004 when Editions Philippe Picquier published Kim Jin-kyung’s multi-volume Cat School. Cat School sold more than 20,000 copies in the shortest period ever right after its publication, defying the negative expectations about Asian children’s titles—a fringe market at best. French publishers duly took notice, diverting their eyes from Japanese books toward Korean ones, albeit at a slow pace. French publishers favored not only contemporary novels mixed with an element of fantasy such as Cat School, but also picture books that bring to life traditional Korean sensibilities and traditions, particularly visually sophisticated titles by Kim Jae-hong and Kim Dong-sung. For instance, titles such as Waiting for Mom (Lee Tae-joon; Hangilsa Publishing Co., Ltd.) and The Life of Buddhist Monks of the Past (Kim Jong-sang; Bluebird Publishing Co.) secured not only positive reviews but also impressive sales in the French market. More important momentum came when Flammarion Group took over Chanok. Once Chanok joined the Flammarion brand, it quickly pushed for contracts with Korean illustrators via agents, playing a greater role in the overseas sales of Korean books in general and actively promoting the potential of Korean picture books in particular. Other publishers in France which continue to publish Korean books in various categories include L'ecole des Loisirs, Bayard Jeunesse, Didier Jeunesse, Mango Jeunesse, Memo, and Pommier. The publishers in question opted for quality titles in various genres and topics that include I Died One Day (Lee Kyunghye; Barambooks), Yujin and Yujin (Lee Geumyi; Prooni Books), The House Where Books Dwell (Lee Young-seo; Munhakdongnae), Sun and Moon (folktale), and Surprising World: The World Cultural Heritage (Yu Soon-hye; Izzlebooks). This selection suggests that French publishers tend to favor Korean books that have not only a solid structure but also a universal appeal that goes beyond geographic and cultural boundaries. 6 list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

3

5 4

6

7

1. Cat School, a multi-volume series Kim Jin-kyung; Illustrator: Kim Jae-hong Munhakdongne Publishing Corp.

5. Surprising World: The World Cultural Heritage Yu Soon-hye, Izzlebooks 2006, 56p, ISBN 8937856034

2. The Life of Buddhist Monks of the Past Kim Jong-sang; Illustrator: Kim Jae-hong Bluebird Publishing Co. 2003, 32p, ISBN 8970576649

6. Yujin and Yujin Lee Geumyi, Prooni Books, Inc. 2008, 286p, ISBN 9788957980132

3. Waiting for Mom Lee Tae-joon; Illustrator: Kim Dong-sung Hangilsa Publishing Co., Ltd. 2007, 38p, ISBN 8935657123 4. The House Where Books Dwell Lee Young-seo; Illustrator: Kim Dong-sung Munhakdongne Publishing Corp. 2009, 192p, ISBN 9788954607347

7. I Died One Day Lee Kyunghye, Baram Books 2004, 192p, ISBN 8990878055

News from LTI Korea

Korean Literature Events at the Guadalajara International Book Fair

Last November, KLTI took part in the Guadalajara International Book Fair in Mexico, the largest book fair in the Spanish-speaking world. Throughout the event, KLTI ran a booth exhibiting Korean books

that have been published in English and Spanish, as well as publicizing KLTI overseas activities. The participation of novelist Eun Hee-kyung, whose work A Gift from a Bird has been published in Spanish, and novelist Park Min-gyu, author of Korean Standards, attracted the most attention. In addition, it was possible to provide Mexican readers with a deeper introduction to Korean literature, thanks to the participation of literary critic Kim Dongshik. KLTI held a total of three events on Korean literature during the book fair. The first was as part of the Guadalajara Book Fair literature program on November 28th, in which novelists Eun Hee-kyung and Park Min-gyu and critic Kim Dongshik all participated, talking to Mexican readers about Korean literature and their own works, and meeting Mexican literary figures for an exchange of ideas. Further events were held outside the main book fair venue. On November 29th, the atmosphere was one of enthusiasm as over 100 Mexican students attended a lecture meeting on Korean Literature held at the University of Guadalajara. A rather special event was the “Ecos de la FIL” program at a local high school, where novelist Eun Hee-kyung and Mexican high school students held a relaxed discussion on Korean literature. During the period of the book fair, the participating Korean authors were interviewed a number of times by the local media, which is a measure of the heightened interest in Korean literature in Central and South America.

KLTI Contest for Up and Coming Translators Hoping to revitalize Korean literary translation and unearth promising new translators to introduce Korean literature abroad, KLTI invited entries for the 9th Korean Literature Translation Contest for New Translators in 2010. The designated texts were “What Makes Up The City?” by Park Seong-won and “The Rosewood Cupboard” by Lee Hyun-soo. There were 110 entries altogether this time, the most popular languages being English and Japanese with 39 and 30 entries, respectively. In all, seven translators were awarded prizes in the 9th Contest for New Translators: Park Kyung-lee for translation into English, Lee Ja-ho for French, Stierand Gunhild for German, Kim Joohyun for Spanish, Elena Kim for Russian, Wu Yumei for Chinese, and Moon Kwang-ja for Japanese. Elena Kim and Moon Kwang-ja attracted particular attention as graduates of the Translation Academy run by KLTI. The birth of a new generation of translators was celebrated at an award ceremony held on November 18, an occasion made all the more meaningful as there was the opportunity for prize winners to meet the original authors of the works which they had translated.

Korean Literature Essay Contest Held Worldwide in 16 Countries Every year KLTI holds a “Korean Literature Essay Contest” with the aims of raising the level of recognition of translated Korean works published abroad and of securing a potential readership for Korean literature. The essay contest, which started in 2005, is held in around 15 different countries, and in 2010 a total of 16 countries took part, including Jordan, Italy, Germany, Vietnam, Poland, the U.K.,

KLTI is now inviting applications for the 2011 10th Korean Literature Translation Contest for New Translators. Like last year, entries will be accepted in seven languages (English, French, German, Spanish, Russian, Japanese, and Chinese). The stories selected for translation are Park Min-gyu’s “The Door of the Morning” for Western languages and Kim In-suk’s “Bye, Elena” for Asian languages. Entries should be sent either by email or post to reach us no later than Monday, April 11, 2011. (enquiries and entries to: newtranslators@klti.or.kr)

France, Bulgaria, Turkey, Russia, Taiwan, China, Mongolia, Japan, and Mexico. In 2011, it is scheduled to take place in 16 countries worldwide, including the U.S., U.K., France, Germany, Spain, Mexico, China, Taiwan, Japan, Russia, Vietnam, Turkey, Poland, Bulgaria, and Thailand. By reading works of Korean literature and writing about their impressions for this competition, overseas readers are able to experience Korean literature more profoundly. In particular, it is anticipated that the high level of participation among younger readers in the various countries will contribute greatly to strengthening the footing of Korean literature abroad in the future.

list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

7

Bestsellers

What We’re Reading

The Scarecrow’s Dance

The Forest of My Young Days

Fiction

Nonfiction

Brida

The Forest of My Young Days

Paulo Coelho, Munhakdongne Publishing Corp. 2010, 351p, ISBN 9788954612999 Brida is a 20-year-old girl who is seeking her destiny. This novel tells the moving story of how her life is transformed as she finds love and goes on to discover her true self. Based on the real experiences of an Irish girl called Brida O’Fern whom Coelho met on a pilgrimage, the book was a household legend for a long time, after the author himself discontinued publication for an undisclosed reason.

Kim Hoon, Munhakdongne Publishing Corp. 2010, 344p, ISBN 9788954613392 This is the most recent work by Kim Hoon, author of Song of the Sword and Song of Strings. The main character, the miniaturist Jo Yeon-ju, explores the themes of the secret meaning of life and awakening insight through her experiences. As the paths of the characters keep crossing and they form connections, the books surveys, in Kim Hoon’s inimitable exquisite style the minute details of life that cannot be spoken or painted.

The Scarecrow’s Dance

La Fille de Papier

Jo Jung-rae, The Literature of Literature 2010, 440p, ISBN 9788943103767 This work is a scathing investigation into the corruption of large enterprises and pariah capitalism. Jo’s previous works have been concerned with Korean modern history, problems of partition and ideology, unconverted longterm political prisoners, and human rights issues regarding prisoners of war that have been ignored by history. By contrast, in this book Jo deals with the present for the first time, illustrating clearly the real paradoxes of the current age and attacking head-on the shameless conduct of the wealthy.

Guillaume Musso, Balgeun Sesang 2010, 488p, ISBN 9788984371071 This work gives full play to the author’s characteristic qualities of arousing suspense instinctively without recourse to intricate embellishments or special rhetoric, and of consistently synthesizing a complex and eventful plot at a buoyant pace. The framework of the book is the story of the love that develops between a bestselling writer and the heroine of his novel.

Le Miroir de Cassandre Bernard Werber, Open Books 2010, 472p, ISBN 9788932910680 This work denounces the “curse” that is heaped on the heads of dreamers who imagine the future. One of the major settings of the novel is a garbage dump, and making this a metaphor for modern civilization, the author does not skimp in portraying the stench of reality that permeates from it. The framework of the story is a 17-yearold girl who can foretell the future but knows nothing at all of her own past, and the course of her struggle with a real world that is full of falseness.

8 list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

Youth, Because It’s Painful

Sweet Little Lies Ekuni Kaori, Sodam Publishing House 2010, 232p, ISBN 9788973816170 A work that deals with marriage and lies, with love and sincere relationships, this book tells the story of the married life of Ruriko and Satoshi that is maintained by secrets and lies. It dryly depicts the loneliness of a reality that you can feel but don’t want to face, when a relationship that started from love ends at the terminal station of “marriage” and can even be described by the word “starvation.”

23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism Chang Ha-Joon, Boo-kie 2010, 368p, ISBN 9788954613392 World-renowned progressive economist Chang HaJoon explains the problems of modern-day capitalism in a simple and clear style that will enlighten even the ordinary reader.

Practice Emptying Your Mind Koike Ryunosuke; Translator: Yu Yun-han Book21 Publishing Group 2010, 244p, ISBN 9788950926298 Buddhist monk Koike Ryunosuke, who guides ordinary people in the practice of Zen in Japan, introduces in this book a “way to rest your brain.” He shows how one can understand worldly thoughts and so free oneself from them by following eight daily practices from “speaking” to “nurture.”

Youth, Because It’s Painful Kim Rando, Sam & Parkers 2010, 320p, ISBN 9788965700036 This book is an anthology of advice from professor Kim Nan-do for young Koreans who are struggling with an uncertain future and the loneliness of youth. Already famous through his lectures at Seoul National University and his Internet site, with warm and sincere words the author implants in young people the courage to overcome their loneliness and anxiety.

These totals are based on sales records from eight major bookstores and three online bookstores from November 2010 to January 2011, provided by the Korean Publishers Association. The books are introduced in no particular order.

An Invisible Difference

Story+Origami: Insects

The Fool Who Only Reads Books

Children's Books Wedding Speeches by a Monk

Story+Origami: Insects

Venerable Pomnyun Sunim, Hankyoreh Publishing Company 2010, 271p, ISBN 9788984314207 The author is the Venerable Pomnyun Sunim, who has vowed to live the life of a bodhisattva (Buddhist saint) to help his neighbors and the world, and has set up the Jungto Society. In this book he imparts words of wisdom on marriage, affection, and love for those dreaming of a happy marriage.

Polliwog; Illustrator: Jung Seung, Izzlebooks 2007, 100p, ISBN 9788937856778 As readers read these stories and fold the paper, they can get to know various insects. The book is structured so that after reading a story about an insect, one can then fold the paper inside the book to make that particular insect. The paper is patterned and colored so that the shape made by folding is extremely lifelike. This is the sixth book in the Story+Origami series. Other books in the series include airplanes, dinosaurs, houses, and around-the-world travels.

2020 War of Wealth in Asia Choi Yoonsik and Bae Dong-chul Knowledge Nomad 2010, 400p, ISBN 9788993322316 This book predicts Korea 10 years in the future, and offers strategies for coping with that future. The prospect presented through abundant simulations is that 10 years from now a war of wealth will break out between the great world powers with the Asian market at center stage, and that Korea may be faced with a limit to its growth.

An Invisible Difference Han Sang-bok and Yeon Jun-hyug Wisdomhouse Publishing Co., Ltd. 2010, 368p, ISBN 9788960511194 By looking at a vast range of topics including philosophy, history, and current management theory, this book sheds light on the mechanisms which lead to good luck and bad luck and presents a golden rule for happiness based on examples of lucky people.

Learning from World-Famous Paintings Writing Factory, Beautiful People 2010, 152p, ISBN 9788994212401 From Botticelli to Chagall, this book introduces over 60 important painters from Western art history. It provides a brief outline of the artists’ lives and shows us their major works, along with a commentary on the content and background of the work. The pictures are arranged according to period, and as we look at them, we can understand how art reflects the changes in society.

Survival in a Tidal Flat Gomdori Co.; Illustrator: Han Hyun-dong, I-Seum 2010, 200p, ISBN 9788937848377 This is the latest book in the ever-popular Comic Survival Science series. Set on Korea’s west coast sandbar, one of the world’s five largest sandbars, it tells the adventures of three children. An exciting story unfolds as the children, shrunk to only an inch in size, get into scrapes such as being imprisoned in a clam shell and fighting with a lugworm. As they follow the story, readers are able to learn about the ecology of a sandbar and about the lives of the creatures that live there.

Gram Gram English Grammar Expedition Jang Youngjun; Illustrator: Appeal Project Sahoi Pyoungnon Publishing Co., Inc. 2010, 172p, ISBN 9788964351109 This English grammar book presents basic English grammar at a level suitable for elementary school students in fun comic book form. There are 15 books in the complete series. It is said that the author, who has a PhD in Linguistics at Harvard University and is currently a professor in the English department at Chung-Ang University, wrote these books for his own son who hates English grammar. From nouns to the present perfect tense, readers can learn from a wide range of English grammar.

It’s OK to Make a Mistake Makita Shinji; Illustrator: Hasegawa Tomoko Toto Book Publishing Co., 2006, 30p, ISBN 9788990611260 This book inspires with courage new students starting elementary school. Children who are relaxed and open at home may be unable to say a word when they start school. The message of encouragement to children afraid of school life is that the teacher will not mind even if you make a mistake, so relax and speak freely. This book always climbs to the bestseller lists as the start of the new school term in March approaches.

The Fool Who Only Reads Books Ahn So-young; Illustrator: Kang Nammi Borim Press, 2005, 288p ISBN 9788943305840 This book tells the story of Yi Deok-mu, a man famous as a great reader in the Joseon era. The author became interested in Yi Deok-mu when he came across a brief reference to him in a book, and after gathering material about him and adding some imaginative details, he has brought Yi to life again. Yi’s passion for books is depicted with wonderful vividness. It is amazing that someone can love books that much!

list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

9

Publishing Trends

Fiction

Puppets Dance to the Tune of Greed and Corruption In 2010, Korean readers rediscovered their passion for political and economic justice as well as the value of thinking based on humanities. Lawyer Kim Yong-cheol, who had ignited a heated debate by exposing the corruption of the Samsung Group where he used to work in 2007, wrote out a book titled Reflections on Samsung in February, asking Koreans to face what Samsung really represents in society. In October, Jo Jung-rae’s latest novel titled The Scarecrow’s Dance hit the local bookstores, encouraging readers to ponder the issues surrounding Korea’s problem-laden economic democratization. In t he novel, Ilg wa ng Group executives at Cu lture Cultivation Center, a unit under the direct control of the chairman, stage a massive lobbying campaign targeting decision makers at the prosecution, the anti-spy agency, the national tax office, government agencies, and the media. The plot revolves around the group’s scheme to pull off a managerial succession and transfer of wealth. The chairman and executives feel satisfied with the lobbying campaign whose total budget is set at 300 billion won for some 2,000 leaders in society—a tiny sum compared with the huge slush funds they get away with. Prosecutors find themselves dragged into the dark waters of corruption and injustice as they have to follow any order, even unlawful ones, from their superiors to survive in the organization. Reporters frequently knock the back doors of the conglomerate to beg for a bribe of 500,000 won, which is at the far end of the corrupt lobbying spectrum. The corporation in question exacts revenge on newspapers which carried not-sofriendly articles, and a high-ranking official at the labor union, who has grabbed the clandestine offer from the firm, offers a false testimony in court, another sign of corruption festering at every level of society.

The Scarecrow’s Dance Jo Jung-rae, The Literature of Literature 2010, 440p, ISBN 9788943103767

10 list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

Many characters are depicted as mere puppets who dance to the tune of corruption. On the other hand, some characters offer a glimmer of hope. For instance, Professor Huh Min continues to push for economic democratization through his newspaper column, even though he gets fired from his post at a university. Lawyer Jeon In-wook, who bolted from the corrupt prosecution, helps civic groups f ight aga inst t he conglomerate. A lso encouraging are the brave civic organizations which venture out to stage a boycott campaign against the products of the conglomerate in question. Jo Jung-rae is no ordinary writer. He published several trilogies of multi-volume novels on Korea’s modern history: Taebaek Mountain Range, Arirang, and Han Kang. He has sold a record 13 million copies. In the author’s introduction of the novel, he writes: “I wrote this novel while yearning for a world where I don’t have to write this kind of novel.” By Choi Jaebong

Nonfiction

Seeking Answers in Tough Times 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism continued to top the bestseller list, outsmarting its rivals by a wide margin. In just two months since its debut, the book sold 300,000 copies. For eight straight months, it ranked No. 1 on the bestseller list of major online bookstores in Korea. The title, written by Professor Chang Ha-joon, who teaches economics at the University of Cambridge, extends the humanities craze sparked last year by the surprising popularity of Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do? by Harvard lecturer in philosophy, Professor Michael Sandel. While Sandel calls on readers to ponder the definition of ‘justice’ from a center-right position, Chang Ha-joon’s book has taken a centerleft stance, offering a implementation guideline for those who seek ‘better justice’ in a capitalist society. Practice Not Thinking by Koike Ryunoske, a monk who graduated from the University of Tokyo, extended its popularity that started last year. Another self-ref lection essay collection that gained attention was Kim Rando’s Youth, Because It’s Painful, which climbed rapidly on the bestseller lists right after its publication late last year. E Jisung’s Leading by Reading also secured a spot on the major bestseller lists. The book, subtitled “Reading Techniques for the World’s 0.1 Percent Elite,” appeals to readers interested in self-help and education by arguing that reading classics in the humanities will open up a door to victory in the capitalist system.

Kim Joong-mi’s Children of Gwaeniburimal (Changbi). With the landmark 100th printing, Ignoramus Samdigi, which is currently on the major bestseller lists, solidified its position as a steady seller as well. The book’s central character named Samdigi, who is ridiculed by his classmates because he is illiterate, yet gets to learn how to read with the help of his friend. This charming children’s book has sold 500,000 copies. In December, Hwang Sun-mi published The Beanpole House Where Wind Stays (Sakyejul), her first young adult novel. Hwang is a recognized author of bestsellers including Leafie, a Hen into the Wild, which sold more than 900,000 copies. In the new title, Hwang gets an 11-year-old girl to narrate stories about marginalized people in a small village near the U.S. army base in Pyeongtaek while the entire country is preoccupied with the ‘Saemaeul Movement.’ The book generated great buzz because it is based on Hwang’s childhood experiences. In the category of preschoolers, Woongjin ThinkBig put out a Korean translation of Anthony Browne’s Bear’s Magic Pencil in November. The book includes not only the author’s own pictures but also various paintings submitted by children who participated in a picture book contest held in Britain. Browne is one of the most popular picture book writers favored by mothers. Other translated titles that drew attention were David Wiesner’s Art & Max (BetterBooks) and Marcus Pfister’s Questions, Questions (BetterBooks).

1

2

3

1. Youth, Because It's Painful Kim Rando, Sam&Parkers 2010, 320p, ISBN 9788965700036 2. Gong Jiyoung’s Jirisan School of Happiness Gong Jiyoung, Open House 2010, 344p, ISBN 9788993824469

By Kwak Aram

3. Just Stories Kolleen Park, Munhakdongne Publishing Corp. 2010, 333p, ISBN 9788993928259

Gong Jiyoung’s Jirisan School of Happiness is a collection of 11 essays that touches on life in a rural area, a serene and refreshing setting that is tempting for people under constant stress from hectic urban living. The book’s instant popularity also proved that Gong, one of the most popular novelists in Korea, has a solid base of enthusiastic fans. In a similar vein, Kolleen Park, a top musical director, published her memoir titled Just Stories. Park demonstrated her charisma by successfully leading an amateur chorus composed of celebrities in a popular reality TV show last year, touching off a syndrome dubbed “Kolleen Park Leadership.” By Bae No-pil 4

Children's Books

Ignoramus Samdigi Reaches the Milestone 100th Printing In the fourth quarter of 2010, a host of heavyweight writers made big strides. At the end of November, for instance, Won You-soon’s bestseller Ignoramus Samdigi (Woongjin ThinkBig) went to its 100th printing, a 10-year milestone since its first publication. The 100-printing club members in the children’s book category include Hwang Sun-mi’s The Bad Boy Stickers (Woongjin ThinkBig) and Leafie, a Hen into the Wild (Sakyejul), the late Kwon Jeong-saeng’s Puppy Poo (Gilbut Children), My Sister, Mongsil (Changbi), and

5

4. Ignoramus Samdigi Won You-soon, Woongjin ThinkBig Co., Ltd. 2010, 95p, ISBN 9788901114705 5. The Beanpole House Where Wind Stays Hwang Sun-mi, Sakyejul Publishing Ltd. 2010, 184p, ISBN 9788958285205

list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

11

Special Section

Korean Children’s Fantasy Books

Mining Tradition, Forging New Enclaves While the children’s book genre in Korea has long been influenced by Western fantasy, an exciting wave of new styles continues to emerge.

The very first Korean children’s story was a fantasy book called The Lily Star and The Little Star written by Ma Hae-song in 1923. Bawinari, a plant with five-colored flowers that lives on the beach, dreams of being recognized and loved in the world. Baby Star up in the sky makes his dreams come true. But the King of the Sky, Baby Star’s father, forbids their reunion. Bawinari withers and dies of a broken heart and Baby Star loses her light and falls into the ocean. Since then, Bawinari comes back to life every year on the beach, and bright light emanates from under the ocean where Baby Star fell. The story has a tragic world view in that the fragile flower and the young star search for their identity and dream of being recognized and loved for who they are, only to have their dreams be crushed. This ref lects the grim realities of Korea under occupation and works as an allegory for the oppressed rights of children and teenagers during the Japanese colonial period. But the flower blooms again and the star continues to shine under the ocean, embodying the idea of hope for a new world, rebirth, and everlasting life. Such a tragic worldview and religious hope went on to become the most important motifs in Korean fantasy books for children. The works of Kwon Jeong-saeng, the most important since Ma Hae-song’s works, prove this theory. The protagonist of Puppy Poo (1969) is Dog Poo shunned by all for being dirty. Dejected by his own hideous form and uselessness, Dog Poo is broken down in the spring rain and turned into fertilizer that nurtures a dandelion. The story of sacrifice from a lowly being to a lovely flower is one of the most famous and beloved tales in Korea. Children’s literature in Korea started with improbable stories, and fantasy became a characteristic of the genre. However, the earlier works were too short and allegorical in nature to qualify as proper fantasy fiction. It wasn’t until the 20th century that Korean writers producing the latter. Democracy brought stability and economic advancement Korean society in the late 1980s, and a new wave of foreign children’s literature was introduced in Korea, heightening children’s literature writers and readers’ 12 list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

1

2

3

4

1. The Lily Star and The Little Star Ma Hae-song, Gilbut Children Publishing Co., Ltd. 2005, 207p, ISBN 8974313545 2. Puppy Poo Kwon Jeong-saeng; Illustrator: Jeong Seung-gak Gilbut Children Publishing Co., Ltd. 1996, 34p, ISBN 8986621134

3. Conclave Oh Jin-won; Illustrator: Yang Kyung-hee Moonji Publishing Co., Ltd. 2009, 459p, ISBN 9788932019963 4. The Secret of Flora Oh Jin-won; Illustrator: Park Hae-nam Moonji Publishing Co., Ltd. 2007, 260p, ISBN 9788932017484

5 6

7

interest in fantasy novels from the west. The catalyst of this new interest was, needless to say, the Harry Potter series that came out in the late 1990s. Fantasy fiction such as the Harry Potter series, The Chronicles of Narnia, The Earthsea Cycle, and Tom’s Midnight Garden had a great influence on Korean children’s book writers. Oh Jin-won and Kim Hye-jin are prime examples. Oh Jin-won changed the landscape of Korean fantasy fiction with her novel, The Secret of Flora, set in the vast universe and its myriad, new and dying planets where different tribes fight to survive. Conclave a story of children traveling through a mysterious world in search of lost memories, healing wounds from the real world, and maturing from the experience, is also considered a grand fantasy. Kim Hyejin created a unique fantasy world through her trilogy, Aro and the Perfect World, The Cane Race, and A Color No One Knows. She draws engaging, diverse narratives from motifs such as the struggle between a perfect and imperfect world and the competition for the cane that symbolizes absolute power. The influence of western fantasy fiction is evident in these writers’ works, but there are also distinctive elements. The novels start out with devices often found in western fantasy fiction, but the story does not end with a clearly dichotomous worldview, a fierce battle between good and evil, or a definite victory or loss. The conclusion of these works is often harmonious, bringing up themes of self-sacrifice, trust, understanding, compromise, forgiveness, and acceptance. Kim Jin-kyung is a good example of a writer who is keen on creating a Korean-style fantasy fiction. He has penned an 11-volume saga called Cat School in which he uses mythology to hold a mirror up to society and solve today’s problems. His works contain in-depth research on East Asian mythology. The pacifist view of harmony and peace over conflict and violence and the incorporation of East Asian mythology have earned the series due recognition abroad. Kang Sook-in, who draws her topics from Korean folklore and history, calls for “a recovery of godliness within us” in The Divine Empire of the World Beyond.

8

5. Cat School, a multi-volume series Kim Jin-kyung; Illustrator: Kim Jae-hong Munhakdongne Publishing Corp. 6. The Cane Race Kim Hye-jin, Baram Books 2007, 599p, ISBN 9788990878441 7. A Color No One Knows Kim Hye-jin, Baram Books 2008, 560p, ISBN 9788990878601 8. Aro and the Perfect World Kim Hye-jin, Baram Books 2004, 528p, ISBN 9788990878113

list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

13

Special Section

The description of heaven, where the story takes place, and the four animal characters, are distinctive features that can’t be found in western fantasy. Yi Hyeon’s Hurray for Jangsu, diverges from the majestic depictions of alternate universes in its comic portrayal of ghosts and the messenger of death from Korean folklore. The comic depictions offset the heavy themes of the novel: children today struggling to survive the cutthroat competition at school and war-generation children trying to put their lives back together in the aftermath of the Korean War. The role of fantasy in this novel is self-evident as the two generations of children meet and work together to restore happiness for children of the present. Korean children’s literature is in its heyday, thanks to young, distinctive fantasy writers. Kang Jeongyeon pokes fun at the empty life of a family too busy to look after their own shadows in A Busy Family, but brings the family back together in the end. Park Hyo-mi’s Diary Library satirizes the strange Korean custom of checking children’s diaries every day in school. The most common theme of Korean fantasy for children is the crushing oppression of the education system and the dream of escape and freedom. Lee Seoung-sook’s Miru from Mars is narrated from the perspective of an alien from outer space who humorously depicts the greed, selfishness, helplessness, and vanity of a family. Korean literature has taken in a century-long legacy of western fantasy fiction all at once and produced an explosive number of its own fantasy fiction in the past decade. These works will go on to form a new strand in the fabric of children’s world literature. The joy of watching its dynamic development awaits. By Kim Inae

1

2

4 3

1. Miru from Mars Lee Seoung-sook; Illustrator: Yoon Mi-sook Moonji Publishing Co., Ltd. 2006, 211p, ISBN 8932017425 2. Hurray for Jangsu Yi Hyeon; Illustrator: Oh Seung-min Urikyoyuk Co., Ltd. 2007, 220p, ISBN 9788980408542 3. Diary Library Park Hyo-mi, Sakyejul Publishing Ltd. 2006, 123p, ISBN 8958281413

14 list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

4. The Divine Empire of the World Beyond Kang Sook-In, Prooni Books, Inc. 2003, 286p, ISBN 8988578945 5. A Busy Family Kang Jeongyeon, Baram Books 2006, 139p, ISBN 8990878314

5

Special Section

Korean Children’s Fantasy Books

Tapping into Mythology, Legends, and Folklore Mythology and folklore reveal the universal hopes, fears, and trials that all living and non-living things share. Incorporated into modern stories, these culturally timeless tales have enchanted children over the ages. Life is at the core of all Korean mythology and folklore. The thread that runs through all Korean fantasy is the hope of life where humans and nature coexist and are profoundly connected to each other. This thread connects humans to gods and nature to humans. It bridges the gap between fantasy and reality, and helps move life along from past to present, and to the future. The Myth of Baekdusan is based on the myth surrounding the birth of Mt. Baekdu, the most famous mountain in the Korean peninsula. The story begins with the birth of the universe and describes the dynamic process that brings us to the birth of Mt. Baekdu. In The Myth of Baekdusan, Mt. Baekdu is a giant with a “white head” (baekdu). The personification of Mt. Baekdu conveys the animistic fantasy of human perceptions of nature, and the idea that the Baekdu Giant exists to protect the Han race demonstrates

a primitive teleological fantasy that nature exists for humans. While The Myth of Baekdusan deals with a supernatural being in nature, Jumong, the Heroic Founder of Goguryeo is about a heroic figure that connects man to gods. Jumong is a being born of the energy of the Earth and the Heavens and is at the same time the founding king of Goguryeo. Jumong’s life, which starts when he hatches from an egg, is an endless string of woe and suffering. But Jumong doesn’t give up his godliness through all the jealousy and banishment. Rather, he gets in touch with his inner god to solve problems every time he is faced with an obstacle. All of nature comes to his aid along the way. Jumong’s quest to establish the kingdom of Goguryeo is one man’s journey to realize his dreams and at the same time to discover his inner sacred being and energy. The epic shaman song Princess Bari starts with a dichotomous divide, as do most myths. Princess Bari is the seventh daughter of a king who is abandoned at birth and raised by an old couple. When her biological parents fall ill, the princesses raised in the palace refuse to go to the land of death to find the elixir of life but Princess Bari gladly takes on the task. Instead of rejecting the paradox of life imposed on her or seeing it as a setback, she sees her life as a process of reconciling the paradoxes of life. What she gains in the process is an ability to overcome death and restore life. The gravity of the Princess Bari myth lies therein. Half a Loaf is born with half of everything—eyes, ears, arms, and legs. But he rises above the taunting and being ostracized to marry a pretty woman and create a happy home. Half a Loaf may appear to be a Korean version of “Beauty and the Beast” but unlike the beast who confines himself to the castle and awaits his fate, Halfie is a go-getter who lives among people regardless of their reaction to his appearance. Nothing can bring him down or create hatred in him. He uses his misfortune for the good of others. We learn through Halfie’s life what it is to overcome one’s fate and limitations to become a truly whole human list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

15

Special Section

The Myth of Baekdusan Liu Jae-soo, Borim Press, 2009, 88p, ISBN 9788943307769

A Mud Snail Bride Han Sung-ok, Borim Press, 1998, 50p, ISBN 8943302606

Jumong, the Heroic Founder of Goguryeo Kim Hyangeum; Illustrator: Kim Dong-sung, Woongjin ThinkBig Co., Ltd., 2009, 48p, ISBN 9788901101194

being. The beast transforms back into a handsome prince at the end of “Beauty and the Beast,” but there is no magic in Half a Loaf. Halfie finds a woman who accepts and loves him despite his grotesque appearance. This implies that Halfie is already a whole person inside and reaffirms one of the fundamental truths in life—that two incomplete beings come together to complete each other. Half a Loaf confirms that Korean folklore is able to create fantasy without entirely departing from this universe. A Mud Snail Bride is a famous example of Korean folklore that involves an animal bride. A bachelor farmer weeding alone in the field bemoans his lonely state, “All this food and no one to share it with!” The empty field answers back, “Share it with me.” The bachelor looks around and finds a snail. The bachelor brings the snail home, and strange things begin to happen. The house is clean, and meals are prepared. When the bachelor discovers that 16 list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

the snail turns into a maiden to take care of him, he takes her as his wife, but an evil king passing by falls in love with the snail bride at first sight. The king tries everything to take the snail bride away from him, but the snail bride uses magic every time to fend the king off. In the end, the king is banished from the country and they live happily ever after. A Mud Snail Bride is to some extent the western equivalent of “The Frog Prince,” but the man the snail bride chooses as her companion is nothing more than a farmer, unlike the frog prince who marries a princess. The plot in which a common farmer finds a lifelong partner in a snail bride from the Dragon Palace under the sea is another distinguishing factor of a Korean fantasy. The Seven Friends in a Lady’s Chamber is a folk tale that personifies the seven tools women in the past used to make clothes—measuring tape, scissors, needles, thread, thimble, hand

Princess Bari Kim Seung-hee; Illustrator: Choi Jung-in, BIR Publishing Co., Ltd., 2006, 30p, ISBN 8949101203

The Seven Friends in a Lady's Chamber Lee Young-kyoung, BIR Publishing Co., Ltd., 1998, 31p, ISBN 8949100207

Half a Loaf Lee Miae, Borim Press, 1997, 32p, ISBN 8943302630

iron, and coal iron. This story shares its structure with “The Shoemaker and the Fairy” by the Grimm Brothers, but the theme and plot are different. When the lady falls asleep while sewing, the seven friends come to life and say they’re the most indispensable tool for making clothes. The lady who lies awake listening to their debate sits up and says that she is the most indispensable. In the end, of course, the seven tools and the lady all acknowledge each other’s worth and admit that none of them can work alone. The moral of the story is that life is complete only when all things living and non-living are connected to each other and live peacefully with one another. By Shin Hye-eun

list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

17

Special Section

Korean Children’s Fantasy Books

Animal Fantasy Fiction Dives into a New Decade Animal fantasy has a long tradition in Korean children’s literature. Since the turn of the century, it has evolved through the efforts of a new generation of writers who have begun to discard past depictions of animals as merely human mirrors. In these tales all living creatures work together towards achieving harmony.

18 list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

Into the Orchard!

Dream of the Oxen

Save the Small Bear

Hwang Sun-mi, Sakyejul Publishing Ltd. 2003, 224p, ISBN 9788971969526

Kim Nam-jung; Illustrator: Oh Seung-min Little Mountain Publishing Co. 2006, 196p, ISBN 8989646243

Kim Nam-jung; Illustrator: Kim Jung-seok Urikyoyuk Co., Ltd. 2007, 188p, ISBN 9788980408504

Animal fantasy takes up the greatest percentage of children’s books. Animal fantasy has had a long tradition in Korean children’s literature as well, and it has been going through a transition from allegorical animal fantasy to stories about animals themselves. Many of these works were written in response to the anthropocentric view of previous works, criticizing the objectification and literary exploitation of animals. Such trends are considered to be a consequence of postmodern thought. Humans are not the only beings on this planet. No matter how advanced our technology, we cannot gain full control over the world, even if we were to build a city of skyscrapers and asphalt roads with the most cutting-edge technology. Hwang Sunmi’s Into the Orchard! is a story about various creatures living in a metropolis. No matter where we are, if we look a little closer and listen a little harder, we can always find a great number of creatures living among humans. This book consists of many chapters, each featuring an animal protagonist who draws a vivid picture of the world seen through its eyes. For example, the way a duck’s webbed feet feel against the asphalt, the starling’s-eyeview of a village, and the smell of a market through the nose of a hungry rat, are described so uncannily as to be almost tangible. The animals’ stories are interwoven in such a way that reflects their harmonious ecology. Kim Nam-jung criticizes the various forms of violence that exist in contemporary society. Dream of the Oxen has an allegorical setting of a fight between the land of oxen and humans over gold. In both the land of oxen and the world of humans, the greed of the ruling class and tribalism send the powerless off to the battlefield. The author points out with anger and sadness that those who suffer most in a war are the weak and the powerless. The fight between humans and oxen is, of course, imaginary, but the mechanism of war in the novel is very realistic. Save the Small Bear is a story of bears who are born the size of fists from the trauma of war and the children who fight to protect them from Nature’s Friend, a multinational conglomerate that mass produces pets by cloning them. Unlike their environmentally friendly campaigning, the company has no qualms about destroying or altering nature for profit. The children’s plot against the company unfolds like a spy mission and captivates

readers as the children try to save the bears from systematic violence on living things. Kang Jeongyeon’s Cocky the Arrogant Dog and The Green-Eyed Elephant feature animals as self-assertive beings. Cocky the Arrogant Dog is about an audacious pet dog named Dodo who is thrown out of its owner’s house because it has gotten fat. Dodo is surprised and hurt, but the audacious Dodo decides to believe that he has never been abandoned. Only those who belong to someone can be abandoned, but Dodo has never accepted anyone as its owner. Dodo refuses to live the life of a comfortable house pet. Instead, he decides to choose the person he would like to live with and become his or her family, friend, and companion. The story of this spunky, adorable puppy will bring courage to children who want to lead more independent lives. Bumbuck the elephant from The Green-Eyed Elephant is also content with living at the zoo. Born after 1,000 days in his mother’s womb, Bumbuck is different from any other elephant. Bumbuck can understand the human language, and is much more intelligent and exceptional than other elephants. He can even communicate with his human friend Hwanee who was born on the same day. He has these sacred powers because he is destined to be the green-eyed navigator of his tribe. But as long as

list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

19

Special Section

The Green-Eyed Elephant

Cocky the Arrogant Dog

A Mouse Without a Tail

Kang Jeongyeon; Illustrator: Baik Dae-seoung Prunsoop Publishing Co., Ltd. 2010, 208p, ISBN 9788971846520

Kang Jeongyeon, BIR Publishing Co., Ltd. 2007, 197p, ISBN 9788949121062

Kwon Yeong-poom; Illustrator: Lee Kwang-ick Changbi Publishers, Inc. 2010, 124p, ISBN 9788936451257

he is trapped in the zoo performing circus tricks, his sacred ability is nothing more than a tourist attraction or a research project. Then one day, Bumbuck sees visions of his long-suffering tribe in Africa and the history of ruthless poaching and confinement. Bumbuck makes up his mind to escape from the inhumane display of the zoo and return to his hometown. His human but true friend Hwanee helps him escape. Quickfoot the mouse who got her tail cut off in a scuffle appears in Kwon Yeong-poom’s A Mouse Without a Tail. Is it hard living with a short tail? Of course. It’s difficult to climb up high without a tail, and she can’t wrap herself with the tail when she sleeps. The brave, optimistic Quickfoot goes to school with a pretty ribbon on her tail instead of despairing about her deformity, but the elitist “pretty mice” bring up the “schoolmouse law” to banish Quickfoot from school: an “ugly mouse” with her tail cut off has no right to live at the school. Quickfoot leads the “ugly mice” to victory in the fight against the tyranny of the “pretty mice.” Quickfoot, mistaken for a hamster thanks to her short tail and pretty ribbon, has the good fortune of being placed in a classroom. Is that a relief? Of course. Quickfoot was happy to be able to live in the classroom surrounded by children. Living with humans was another fun activity and an adventure for her. The smarter, bolder animal characters of the 21st century think of humans as partners, not masters. The young Korean writers of the 21st century are reexamining the relationship between humans and animals through animal fantasy. Kang Jeongyeon writes in her afterword, “Humans may think they have tamed nature, but they’re powerless before what nature can do. Even so, humans have not learned to be humble before nature. Humans are busy digging through mountains, overturning rivers, and remodeling the world to make it more convenient. Little do they know that nature will strike back with a catastrophe a hundred, or a thousand times more frightning than what humans are capable of. How dare they?” Korean writers are starting to portray animals for what they are, untainted by human reasoning and stratification, to dream of a world where all living creatures live in peace and harmony. By Cho Eunsook

20 list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

Special Section

Korean Children’s Fantasy Books

Child’s Play Gets In Touch With Reality When children look with their imaginations instead of their eyes, they see worlds long lost to adults. Books loved by children and parents alike continue to explore the limitless creativity of children. A small fight breaks out in the neighborhood playground. “My dinosaur turns purple in the face that fumes at the nose!” “My dinosaur turns red all over and breathes fire when it talks! My dinosaur is scarier than yours!” The children are having a screaming match over how their toy dinosaurs changed when angry. Watching the children’s adorable argument, it occurred to me that they weren’t talking about their toys. They were talking about real dinosaurs, and their dinosaurs were standing tall behind them, backing up their arguments. We adults couldn’t see the dinosaurs, but to the children, the dinosaurs were really there. It’s hard to believe, but children’s lives are full of such magical moments. To them, fantasy is how they live and play. Hanuri in The Story of Hanuri is a lion hunter. To hunt a lion, one must be as fast and brave as a lion. Hanuri dashes through the African plains and finally catches a lion! But Mommy has no idea what it takes to hunt a lion as she yells, “There are no lions in our house!” Tsk, poor Mommy. What is that creature struggling in the pillowcase if not a lion? Adults are only interested in the end result of things. They have no clue why something happened. The protagonist of How I Caught a Cold, well, caught a cold. Why did she catch a cold? It was the ducks. A whole flock of ducks missing feathers came to her last night. The child pulled out the down from her parka and planted each feather into the ducks. Naturally, her parka became thin and the child caught a cold. But Mommy says, “You caught a cold because you kicked off the covers.” Mommy will never guess in a million years how much fun the child had playing with the ducks all night. Adults are blind even to the things right before their eyes. What they can’t see, they can’t play with. The main character of A Subway to an Aquarium sees a beautiful ocean outside the subway window. The train goes underwater. There are fish swimming outside the window. If you want to, you can always open the subway window and go swim with the fish. You can even meet a whale! But what’s the child’s father doing? Hey, mister! Your child just went after that whale. Daddy doesn’t know that his child went off to see the whale. He doesn’t even know he’s riding the train through the ocean. But not all adults are fools. Look at the wise adults in Cloud

Bread and The Moon Sorbet! Mama Cat makes bread out of the cloud that her kittens brought home, and the children who eat the bread float through the sky. After eating Mama’s cloud bread, Daddy doesn’t have to be stuck in traffic anymore. He can fly to work! Mama deserves a pat on the back for baking cloud bread. What about the old lady who made sorbet out of moon drops on a hot, hot summer night? The neighborhood had a cool summer, thanks to the old lady’s moon sorbet. The moon sorbet was delicious and refreshing, but what to do with the moon that’s gone? No worries. If the old lady knows how to make moon sorbet, she’ll of course know how to restore it back in the sky. Thanks to these smart adults, there is hope for adults all over the world yet. Whether or not adults notice, the fantasy in a child’s life goes on. In I Like You Just As You Are, Mimi and Otto get into an argument over Mimi’s ribbon. She’s wearing a pretty ribbon in her hair, but Otto doesn’t notice. Mimi becomes upset and wishes Otto’s eyes were larger so he could see her ribbon better. As soon as she says that, Otto’s eyes really become huge! Mimi proceeds to fix Otto. “Your nose is too flat!” “Your voice is too soft!” Otto changes with each incantation. In the end, Otto turns into an enormous monster. Does Mimi like the monstrous Otto? What would be Mimi’s last wish? The characters of Hare, Wolf, Tiger, and Dammi don’t take orders from adults anymore. Going out to run errands, Mama Rabbit tells Baby Rabbit not to open the door “if the wolf comes a-knocking.” The Baby Rabbit braces herself for the scary wolf ’s visit. She waits all day for the wolf with the fabled sharp fangs. But he won’t come. Where is he? So instead, the baby rabbit sets out to find the wolf. The baby rabbit goes to the wolf ’s house to find

list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

21

Special Section

How I Caught a Cold Kim Dongsoo, Borim Press, 2002, 28p, ISBN 9788943304799

A Subway to an Aquarium Hwang Eun-ah, Marubol Publications, 2001, 40p, ISBN 8985675877

Cloud Bread Baek Heena, Hansol Education, 2004, 38p, ISBN 8953527058

there’s no scary wolf. Instead, there’s a frightened little wolf waiting for the scary tiger. The baby wolf and the baby rabbit set out in search of the scary tiger. At the tiger’s house, they find a baby tiger waiting for the scary hunter. So the baby rabbit, the baby wolf, and the baby tiger go to meet the hunter who turns out to be a child. Their adventure brings them new friendships. It would have been so boring if they’d listened to their mothers and stayed home! No genetic mutation is required for children to turn into animals. If a child meows, his friend believes he has transformed into a cat. No computers or virtual reality are necessary for a child to see his friend as a cat, like the children in The Cats. Children can turn into various animals such as tigers, turtles, and chameleons like the child in Ouch! It Stings! The child turns into a different animal because he doesn’t want to get his flu shot—a 22 list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

truly important reason to morph into another animal. I visited the playground again. This time, two girls were discussing their angry mothers. “My mommy has steam rising from her head!” “My mommy turns into a very, very strong monster!” Next to the girls was a small group of children chasing a puppy. To the children, the puppy is no different from a lion. If it happened in their heads, it really happened in real life. For a child, fantasy is where they play and it is real to them. Therefore, I have no doubt the girls’ mothers don’t just look like monsters when they’re angry—they actually turn into monsters! By Lee Jiyoo

I Like You Just As You Are Kook Jiseung, Sigongjunior, 2008, 207p, ISBN 9788952753045

Hare, Wolf, Tiger, and Dammi Han Byoung-ho; Illustrator: Chae Insun, Sigongjunior, 2000, 20p, ISBN 8952709063

The Cats Hyeon Deok; Illustrator: Lee Hyoung-jin, Gilbut Children Publishing Co., Ltd. 2000, 28p, ISBN 9788986621730

Ouch! It Stings! Kook Jiseung, Sigongjunior, 2009, 36p, ISBN 9788952756633

list_ Books from Korea

Vol.11 Spring 2011

23

Interview

Kneading, Baking, Freezing, and Thawing Worlds of Imagination Picture Book Artist Baek Heena

Baek Heena creates picture books that are delicate, fanciful, and entirely readable. Her artistry is matched by a perfectionism and a lavish attention to detail in her quest to make memorable stories. In one of the alleys around Ewha Womans University in Shinchon, Seoul, there is a small children’s bookstore called Chobang. A hidden gem for children’s book enthusiasts, it’s a cozy little nook where readers can discuss new books and authors. I came here a while back to see a small exhibit and saw the original illustrations for the storybook, Cloud Bread, for the first time. It was a story about a family of cats baking and eating cloud bread from clouds that descend from the sky on a rainy day. It was simple yet captivating. The most surprising part of it was the vivid reality of the world created by the artist by mixing two-dimensional and three-dimensional media. I could almost smell the cloud bread baking in the cat family’s kitchen. The children sitting in a corner of the gallery reading Cloud Bread pressed their noses against the pictures to smell the bread. They spread their arms to imitate the cats flying like clouds in the sky. They seemed ready to go home to their mothers and beg for cloud bread. Cloud Bread put author Baek Heena on the map worldwide in 2004. Baek started working on Cloud Bread after the birth of her first child in 2004, and received the honor of “The Illustrator of the Year” at the Bologna Children’s Book Festival in 2005. In Korea, Cloud Bread is known to be one of the best picture books published in the first decade of the 21st century, not to mention its impressive sales record of 450,000 copies. It has been translated and published in France, Japan, Taiwan, China, Germany, and Iran. The book was turned into an animated film, a musical, and an art installation, solidifying its place among Korean children as a beloved new classic. Baek Heena has since written and illustrated The Red Bean Porridge Granny and the Tiger, The Moon Sorbet, and Last Evening, sharing her inventive visual art with the world. Baek is known for her uncompromising, meticulous works. At her studio by the Han River, art supplies and tools of various shapes and sizes fill the shelves, reminiscent of the workshop of a craftsman. She is an artist who creates the most dazzling stories with the most honest, persistent effort, which means a huge time investment. If she has to light every room on the set the size of her palm, she finds a dozen light bulbs barely 0.5mm in length and finds a way to wire them all. She makes every balcony by hand using wire, and installs tiny air conditioners. In the rooms