9 minute read

North Kato Summer 2024

Open Micus: The Ballad of Eddie

BY NATE BOOTS

Eddie Micus, a North Mankato resident for the last twenty or so years of his life, passed away of a heart attack in February. He was born in Fort Dodge, Iowa, was drafted into Vietnam, and—after being shot and nearly killed during his time of service—he started a family with his wife, Jean, who gave him three sons: Ed Jr., Mark, and Will. The young family settled in Southern Minnesota.

Many students would come to know Eddie as Mr. Micus throughout his days working a high school English teacher (at Storden-Jeffers and New Ulm) or later, as a collegiate writing tutor and director at MSU-Mankato. Scores of writers associated with MSU’s longtime successful MFA Creative Writing program came to know him as a friend, advisor, and fellow lifelong student of writing. For many years, he was the best writer, lyrically, in town. He published two literary volumes: one a work of reality-based fiction called Landing Zones (2003), and the other a prizewinning book of poems entitled The Infirmary (2008).

Eddie has returned to the elements, now, so to speak, which seems of a natural course. He was such a down-to-earth sort of person that it was as if he was almost in the actual dirt—or emanating up from the soil like some occasionally-flowering, hardscrabble weed. He could appear, and act, scruffy, beleaguered, or sea-salty. But, in many situations, especially the right situations, he bloomed and dazzled. He was funny, charming, and an expert conversationalist—a fascinating orator but also a wise and ready listener. He was tortured by things he’d been through: childhood trauma, being drafted into Vietnam, sustaining injury in battle, the horrors of war, losing one son to a car accident and caring for another later diagnosed with schizophrenia, laboring through the rigors and regrets of divorce, suffering from PTSD, struggling with the bottle, and writing in relative obscurity.

But Eddie Micus had an ability to synthesize the things he struggled with into bits of beauty, turning brambles and cockleburs into daffodils and roses. He transposed aspects of his pain and suffering into lush literary work or valuable classroom lessons or simple acts of kindness or generosity. This talent of his was rare and something truly blessed—it was his special power. I saw him wield his special power upon the young, upon the middle-aged, and upon the old, and he did it to me, too.

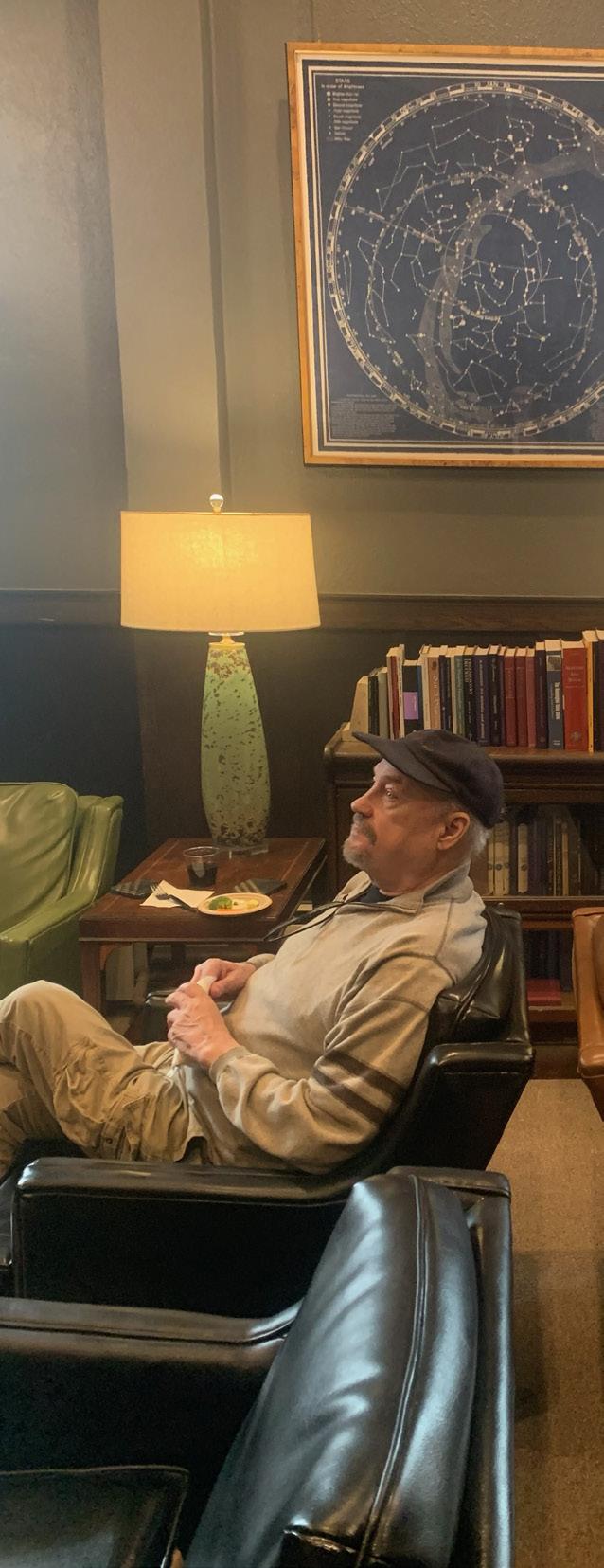

I first met Eddie when I moved to Mankato in the summer of 2001. My Grandpa Gordon was a school superintendent who had hired Eddie as a teacher at Storden-Jeffers, and so Eddie taught both of my parents in high school, as well as various aunts and uncles. My mother babysat Eddie’s boys a time or two, and Eddie watched my dad play basketball for the Chiefs. So, there was some family history with Eddie, and when I met him, he was as advertised. He stood about five-foot-ten, a bit wild-looking with ice blue, diamond-shaped eyes, a black mustache, and curly hair extending out the back of an ever-present ball cap. I soon began visiting him in the tutoring center where he worked at MSU, and he occasionally came by the grad student offices in Armstrong Hall to say hello, or we ran into each other at literary events such as the Good Thunder Reading Series or at an open mic reading event that my Uncle Mike Lohre (another Micus writing disciple) had started ten years prior called Writers’ Bloc.

By the start of my second year of grad school, I had taken over the reins of Writers’ Bloc, and I was looking to upgrade the flagging event to something more vibrant than 15 to 20 students and professors getting together for an evening of meandering readings and a few odd drinks down at the old Jazz Club. One of the ways I decided to do this was to change the venue. I moved the event to the What’s Up Lounge above the Oleander Saloon, where we’d have a nice stage and some relative peace and quiet in a great listening room. Then I found an old, broken-down podium at MSU that I fixed up and hauled over to the What’s Up—a person standing behind a podium exudes authority!

In an attempt to draw in a wider audience, I made flyers and posted them not just in Armstrong Hall but all over campus at MSU, and even at other places around town such as grocery stores, coffee shops, and liquor stores. I added a musical intermission to the program, and I made a rule that all readers’ timeslots were to be for seven minutes maximum, which’d move things along. And, perhaps most importantly, I stacked the deck of readers, personally inviting the best of the best writers to read first. I would choose the writers whose pieces had humor, heart, and punch, the fictioneers who were masters of short scenes, the poets whose words rang out like a song. I put Eddie Micus first. One of the first pieces Eddie read was a little flash nonfiction piece called “Chickpeas.” Its blend of humor and poetry is Micus at his very best, and it set the bar to a more preferred height for the Writers’ Bloc readers.

“Chickpeas”

by Edward Micus

In a co-op. Off Nicollet Avenue in the middle of the block, with a yellow awning and a canary in one window. I had only stopped in from the rain, my life clipping along just fine. This small shop was crammed with everything ever grown or dried, from avocados to herbal tea, and between the squash and new potatoes this lovely woman in an apron, holding a ripe squash in her hand, her eyes the color of chickpeas. “Okay, don’t stare,” my just fine life said to me, “the rain has stopped.”

The next day I was back and went up to her and said, “Some of these, please,” and held open the bag while she scooped them in. I still have that first pound of lentils sitting in the dark of a cupboard somewhere, waiting for Godot. Tuesday it was corn meal and rock salt, Wednesday a string of garlic that hung above her head. Two eggplants on Thursday to learn Thursday was her day off, that her name was Anna. And Friday she smiled me back my change and said, “Nice to see you again.”

All the next week this went on. Isn’t it odd how a man will go up to his neck in quicksand before he’ll go up to a woman? Okay. It would be Monday then, late Monday, with a scrap of wind caught in the awning, dusk with its small hand on the glass, and she was huddled over a bin of something I didn’t know the name for. When she looked at me, she brushed away the hair from her eyes with the back of her hand, and she was so beautiful you would love her in a very small room or in no room at all.

“Anna,” I said, going up to her, that word a stone for the throat, “Anna,” I said, “my pantry’s full.”

This piece had people nodding along and delighting in the word play and was the kind of piece Eddie would write more of and read at subsequent open mics in the next couple years as Writers’ Bloc became a thriving, well-attended event. Eddie would often finish his readings with a poem, probably one that stuck in one’s cranium for the next day or two or week. His poems did what the best poetry does: make you sit up and pay a closer kind of attention, the kind that elicits gooseflesh, the kind that makes leaps, the kind that makes the heart leap. The kind that was, itself, like Eddie Micus at his finest: arresting and poignant.

“Arm-Wrestling”

by Edward Micus

They have propped their elbows on the back table at Maggie’s Saloon, two hinges primeval, evolved in natural rubber and bone, a fulcrum where a billion years have swung, and above each hinge a tattoo farm. Now we have the hooking up, the forearms join along a seam. It could be a kind of mating. Two thumbs embrace to make a hitch, then palm to palm, eight fingerhooks. Inside each arm a band of muscles, strung and tuned, plays the battle hymn.

The heart shifts gears, blood hurries along, something triggers in the groin. I know a woman who, if you love her enough, will lie beside you and settle the back of her hand along your cheek, or your temple, say, with the palm facing out to show there is nothing in the hand a kind of surrender, if you like, as if you had won.

“Three Sons”

by Edward Micus

I have three sons one day. If the weather with their mother is fair by phone, I drive to Sunday town, pull up to a yellow house. Three boys step down and fall across the lawn. The oldest one wears a gold circle in his ear. The middle boy is mostly grown. He still waves a child’s hand. They fill the car with words. I split my heart into thirds. Last week I swear we had a bigger car.We burn hot dogs at the park.I count their bones.At 9:00 they become un-sons again.I say goodnight and turn them in.“Gotcha last,” the youngest says. Every mile of highway back asks what father is.