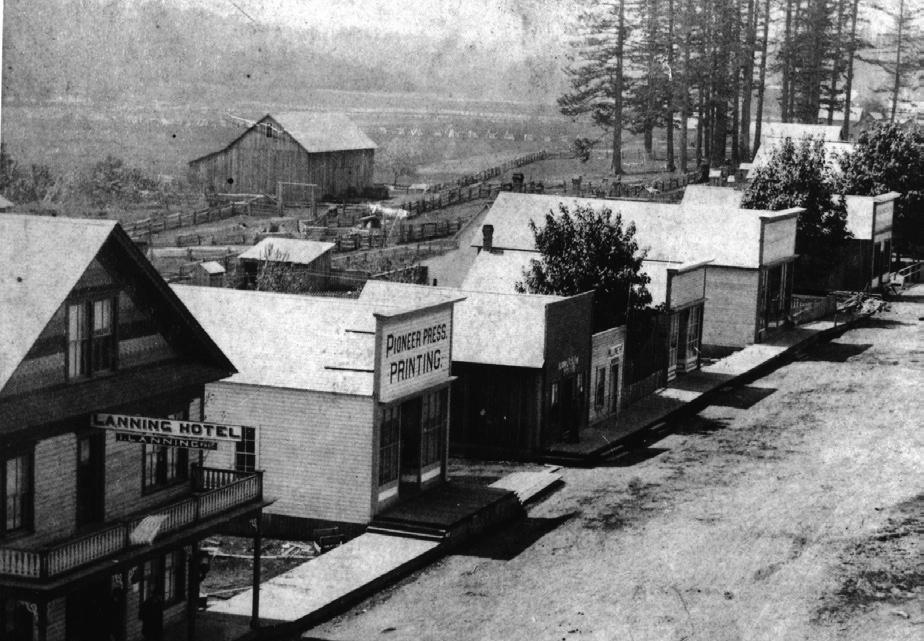

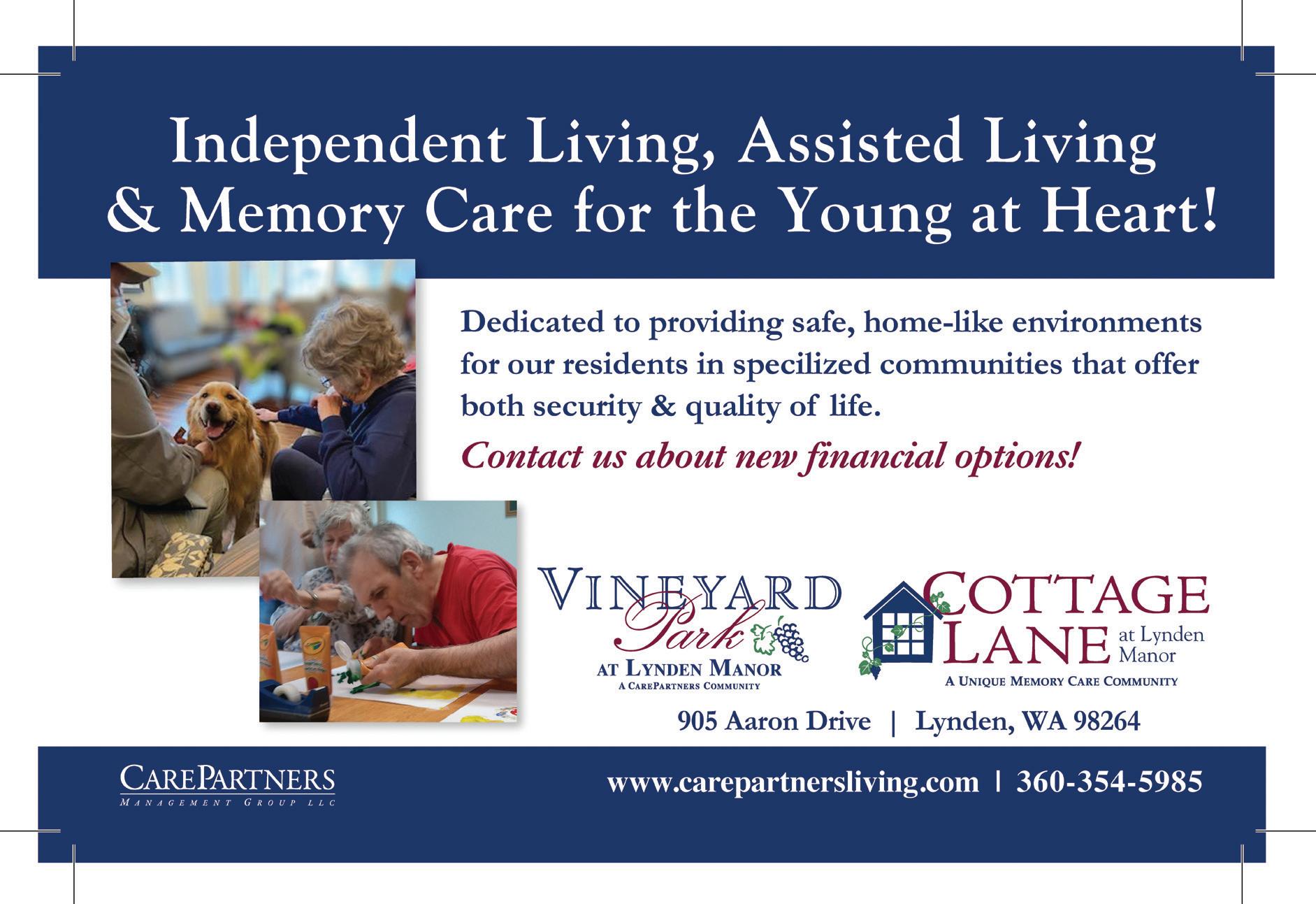

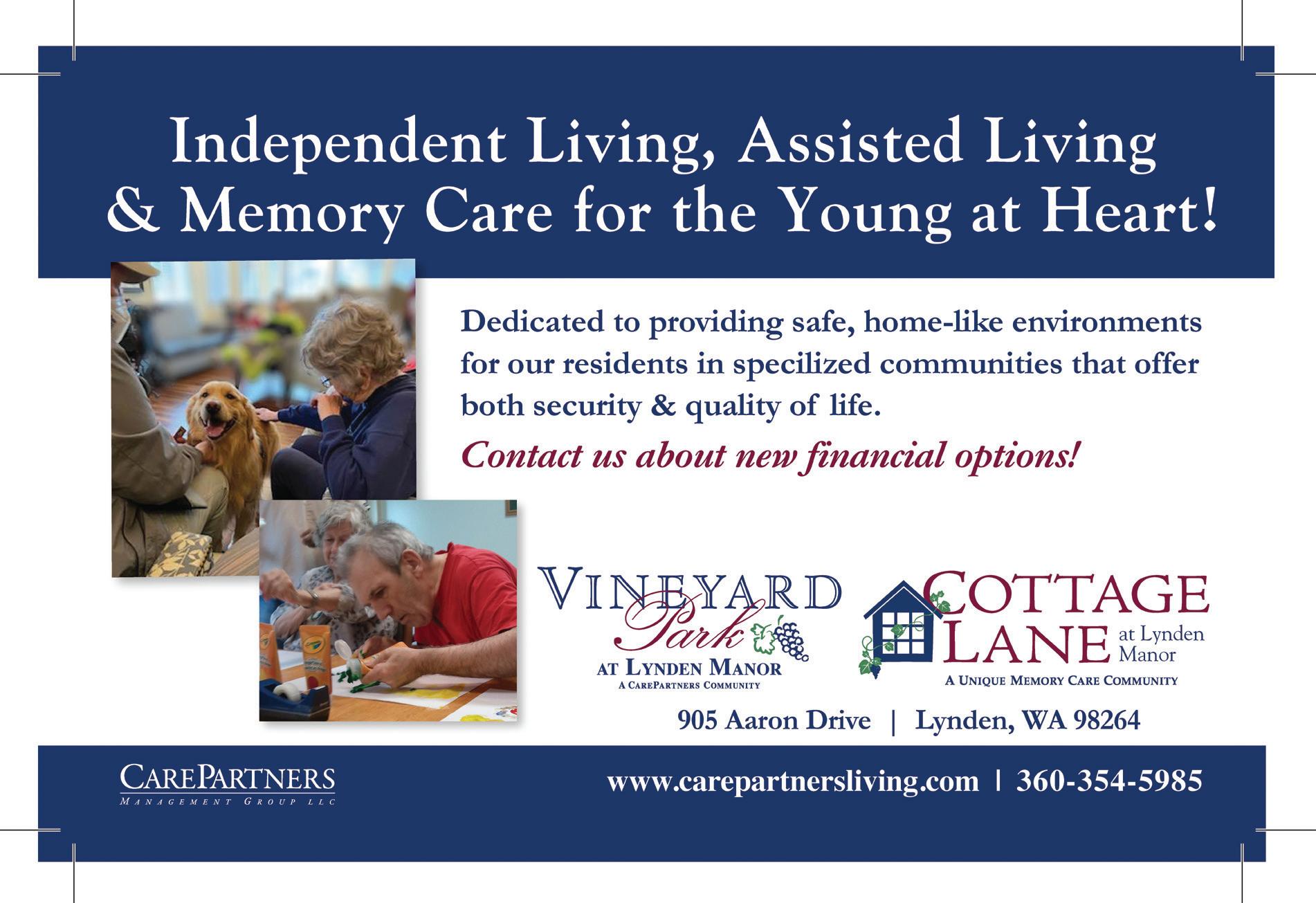

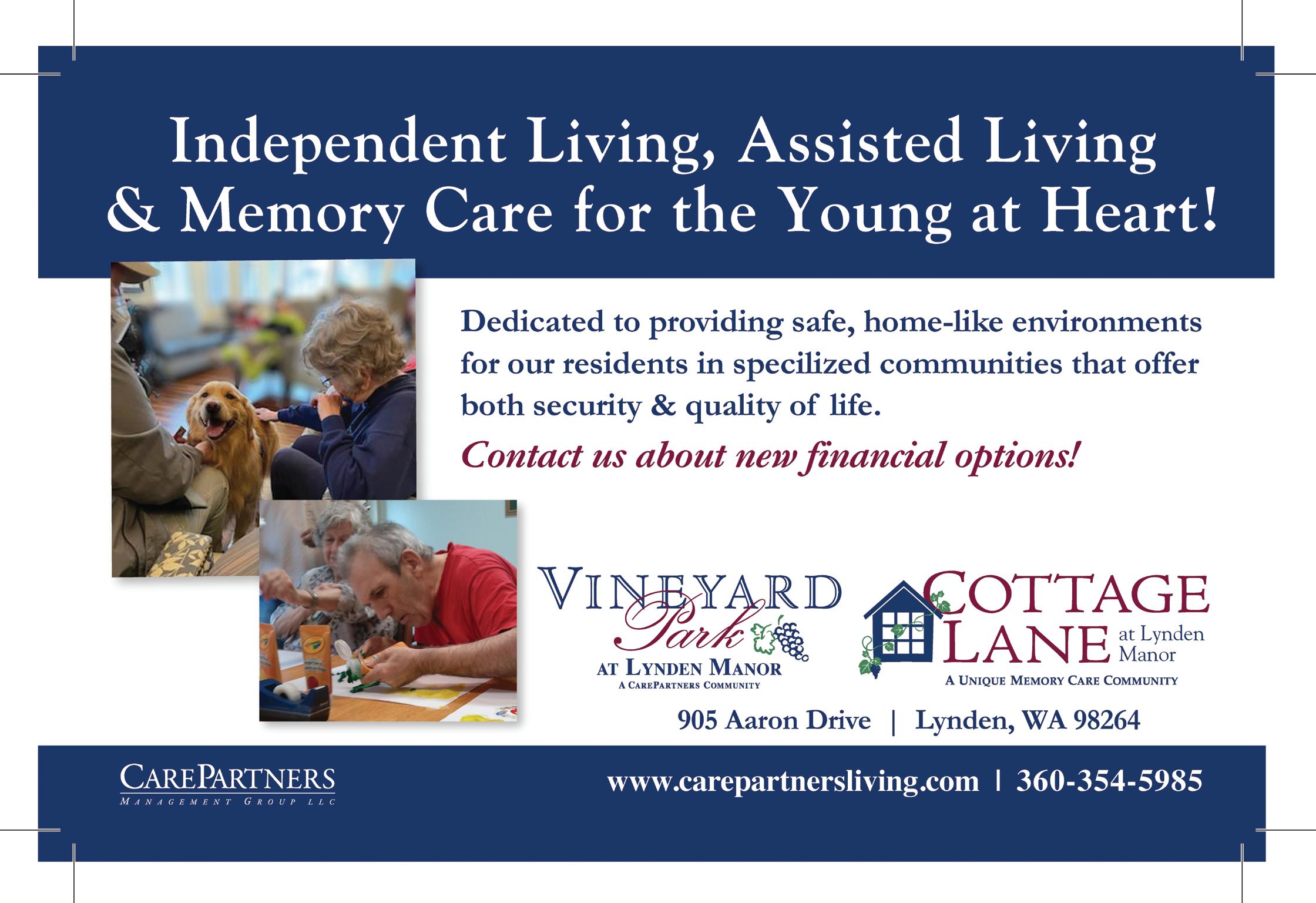

July 28-29 are the dates for this year’s Whatcom Old Settlers Association’s annual picnic. The two-day event is at Pioneer Park, 2004 Cherry St. across from the Phillips 66 ball fields. (Bill Helm/Lynden Tribune)

Annual picnic July 28-29 with parade, car

It was back in 1895 when the Whatcom County Old Settlers Association formed in what we now call Bellingham’s Fairhaven district. A year later, the group held its first picnic, out in Birch Bay. Admission was 50 cents, or what folks used to call four bits.

Only twice since 1896 has a year gone by without an Old Settlers Picnic: 1942 and 2020.

July 28-29, Whatcom County Old Settlers Association will celebrate 127 years of memories at Pioneer Park, 2004 Cherry St.,

See Old Settlers on 5

For many years, the last weekend of July has been dedicated to celebrating the pioneers of Whatcom County. On July 28-29, the Whatcom Old Settlers Association will again encourage locals to learn the history of various families and their paths of immigrating and settling to the area.

Up until COVID-19, Lynda Lucas had worked in the association’s registration cabinet, learning to do various jobs. She was elected to be the association’s president in 2020, which was a tough start because the event was canceled that year. She was then elected for the position in 2021 and again in 2022. Lucas explained that if it were not for her family’s history, she would not be here doing what she loves.

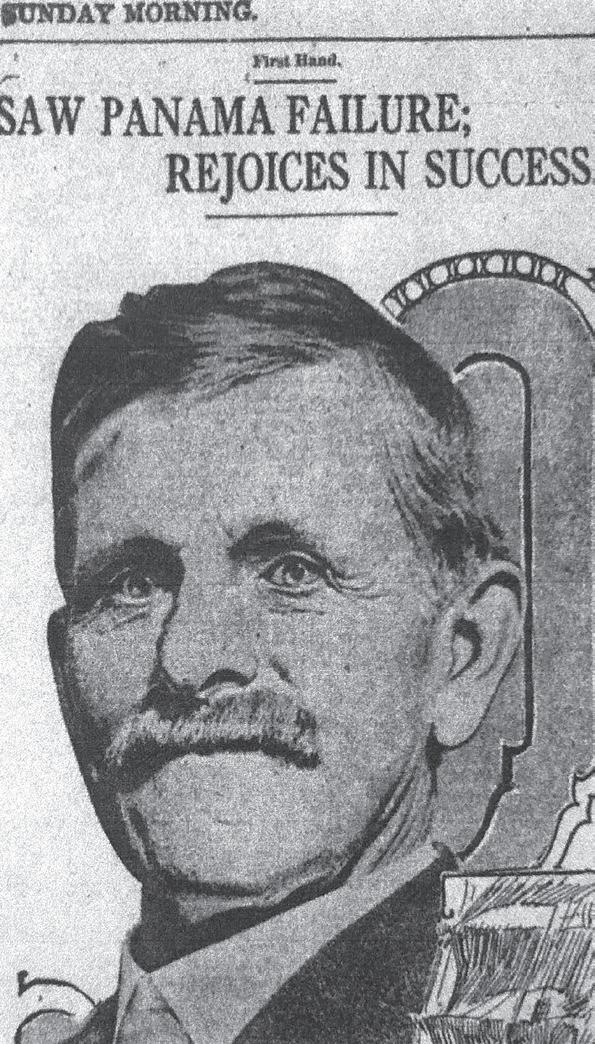

Moving to Washington

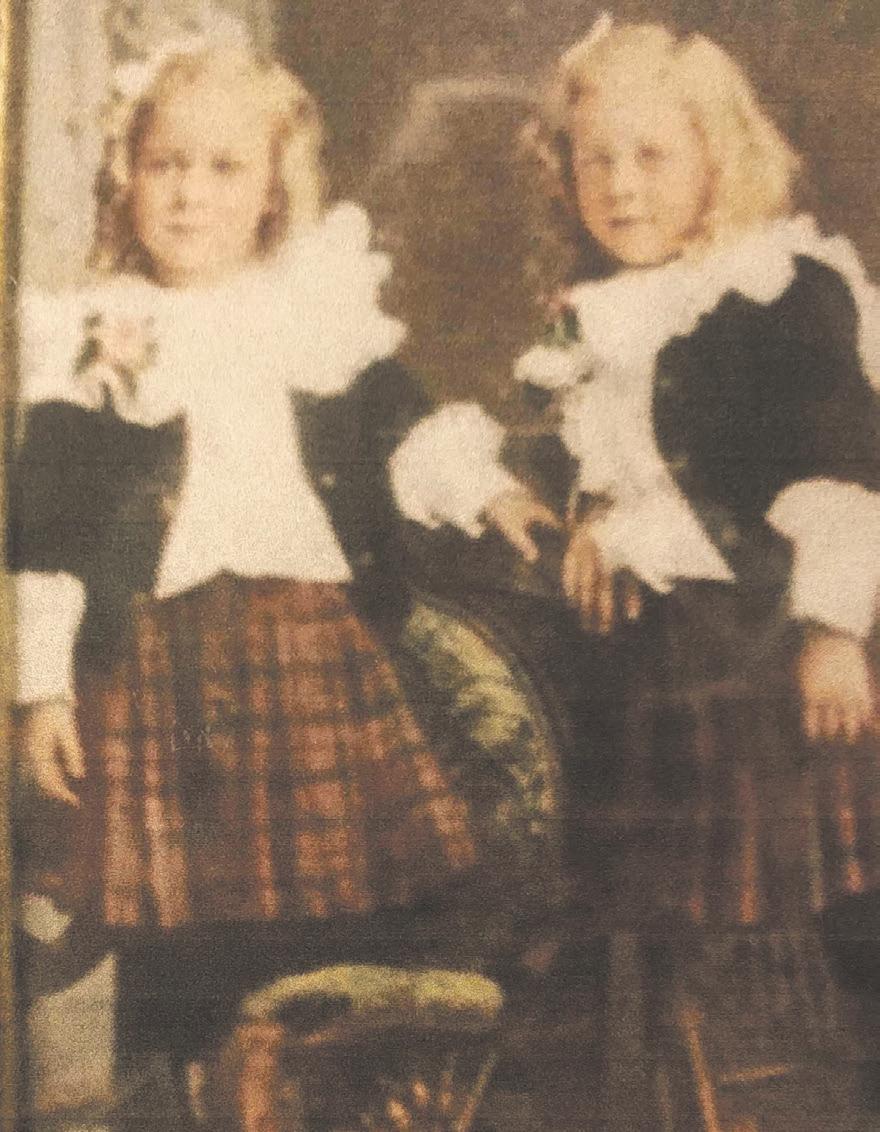

Lynda’s great grandfather, Sea Capt. John Leonard Crowell, left Barnstable, Massachusetts in 1888. John traveled to the west coast and ended up in Bellingham Bay, in Fairhaven, around 1890. He married Charlote Lee, Lynda’s great-grandmother, in New Westminster, which is just outside of Vancouver, British Columbia. In 1902, Charlote came to the U.S. with her twin sons. One of the sons, Robert Stanley Crowell Griffin, would become Lynda’s grandfather. The other, her uncle, was Roy Griffin.

A few years later in 1905, Charlote married Hiram Oliver (Mike) Griffin, who had lived in Whatcom County for a few years already. He was the son of Levi N. Griffin who was the

See Lynda Lucas on 6

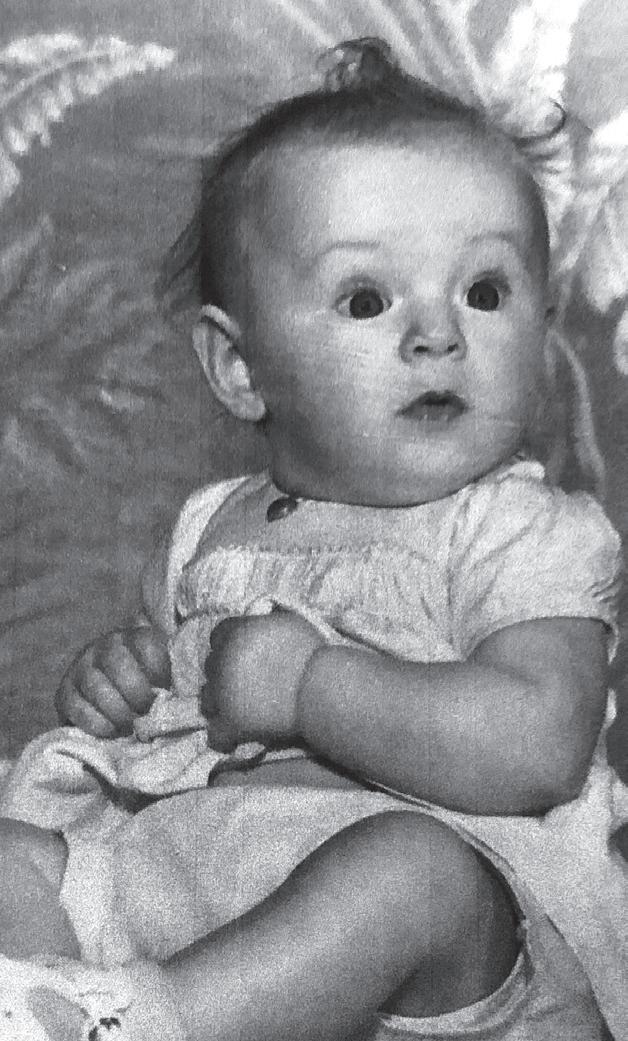

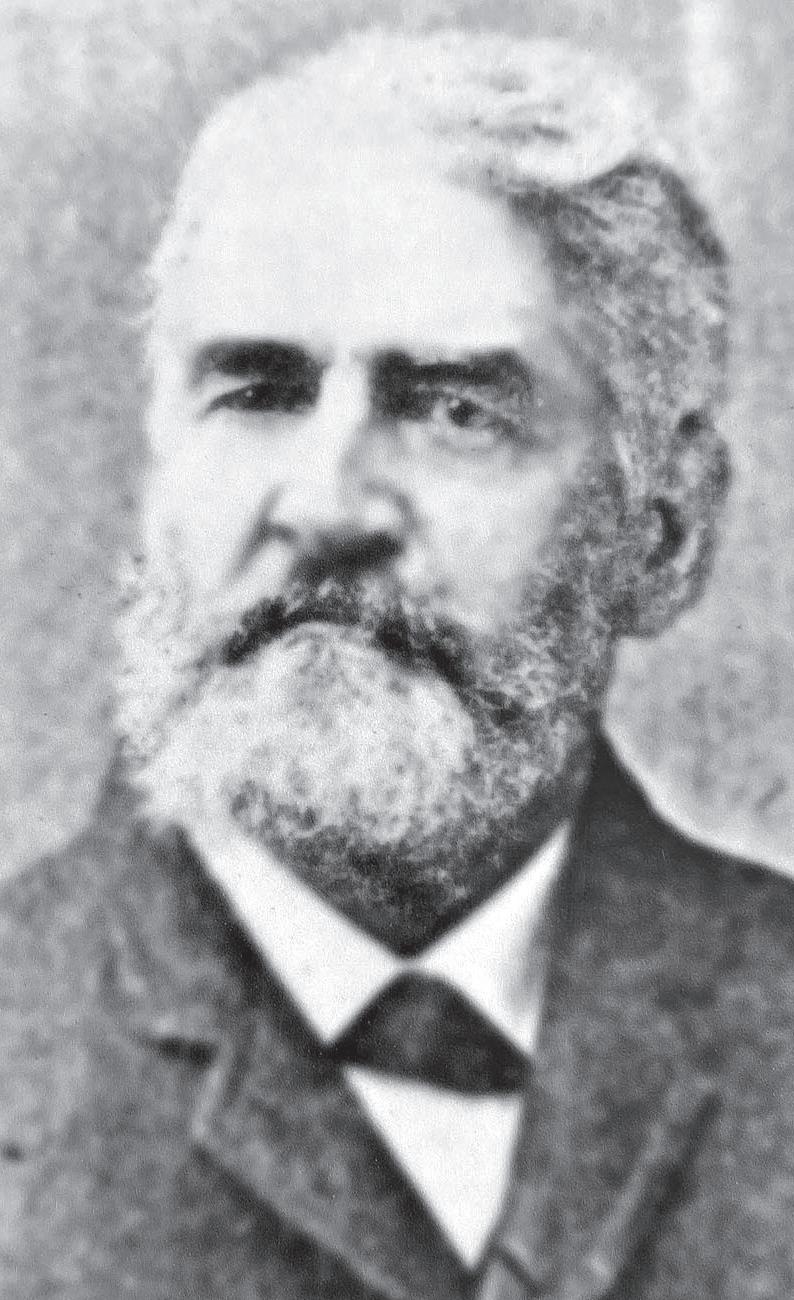

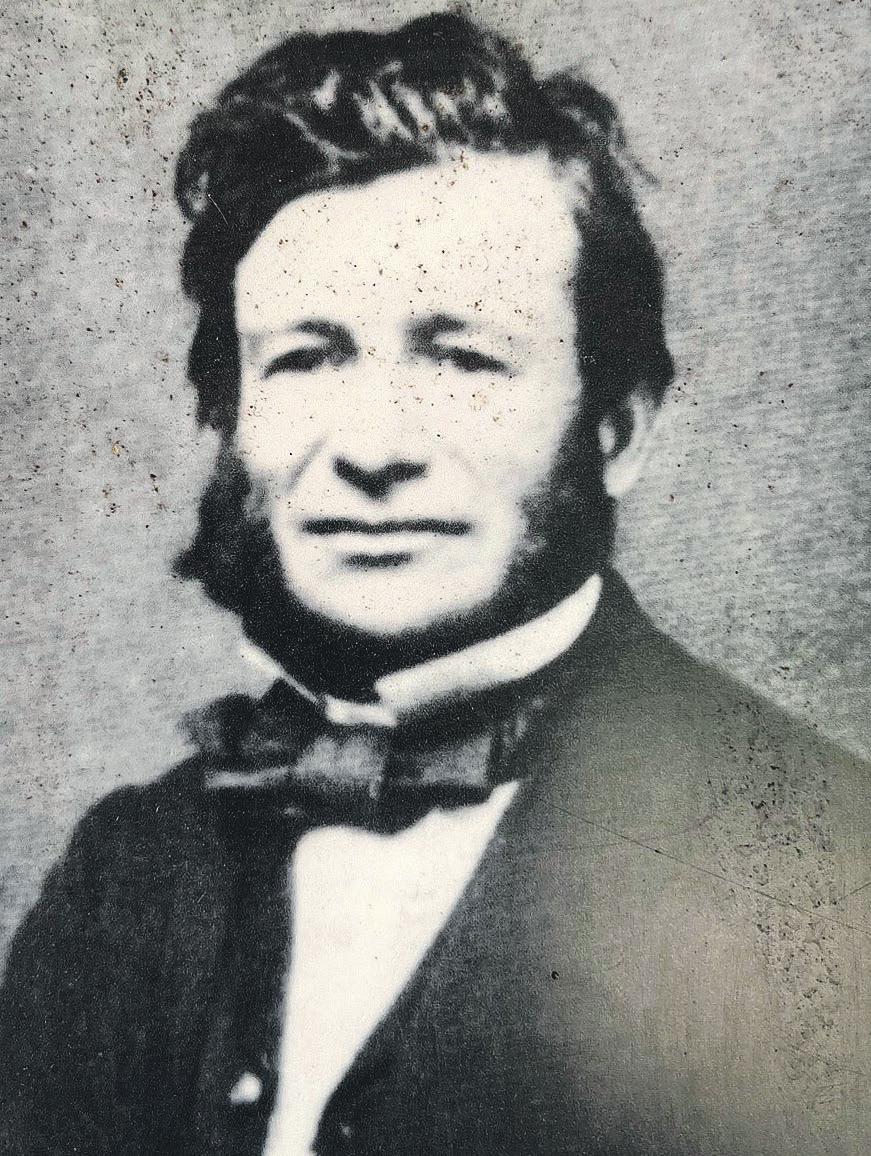

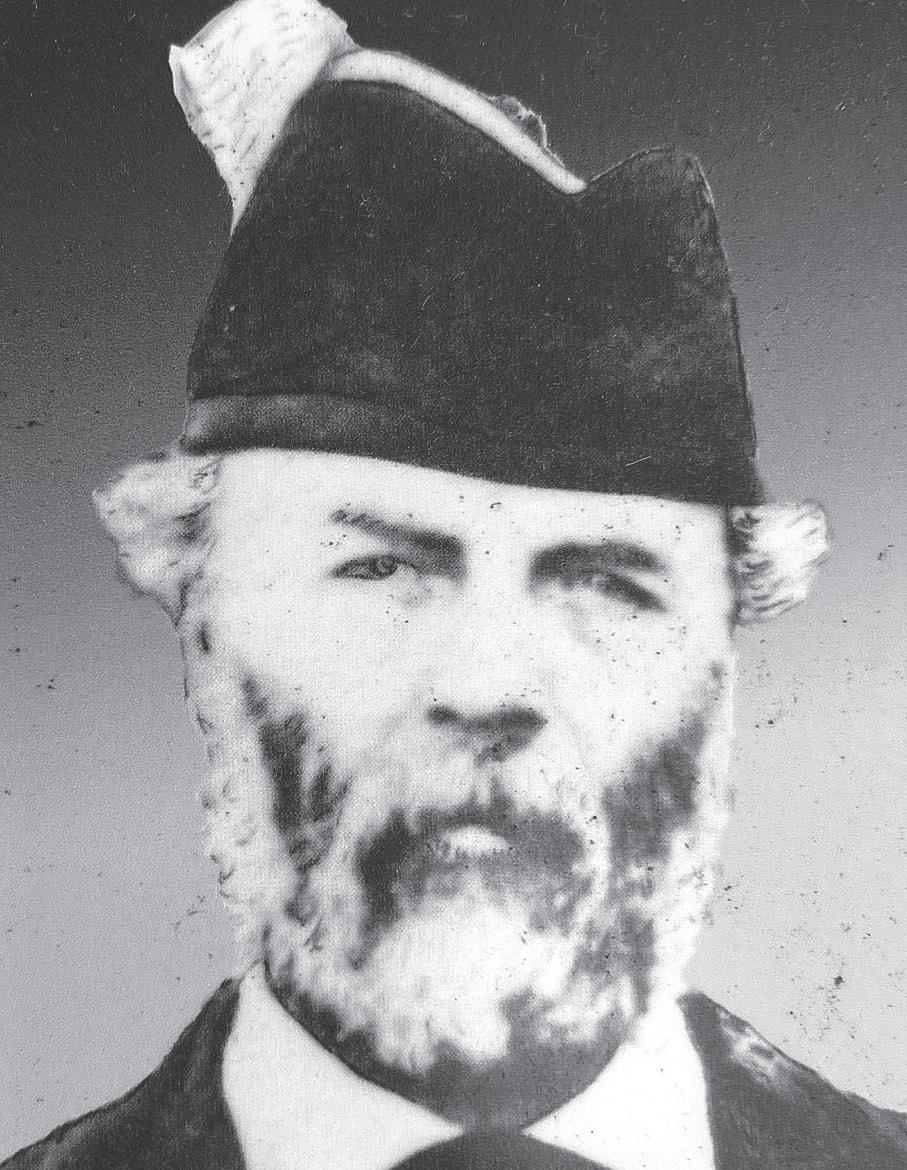

Lucas as a small child. Sea Capt. John Leonard Crowell, pictured, is Lynda Lucas’s greatgrandfather. John traveled from Massachusetts and ended up in Bellingham Bay, which was the start of Lynda’s heritage. (Photos at left and far left are courtesy Lynda Lucas)

Lynda Lucas, above, is pictured talking with Lynden Tribune and Ferndale Record staff earlier this year about the state of the annual Whatcom Old Settlers Picnic and Parade. The Whatcom Old Settlers Association needs more volunteers, especially younger people, Lucas said. (Bill Helm/Lynden Tribune)

Lynda Lucas, above, is pictured talking with Lynden Tribune and Ferndale Record staff earlier this year about the state of the annual Whatcom Old Settlers Picnic and Parade. The Whatcom Old Settlers Association needs more volunteers, especially younger people, Lucas said. (Bill Helm/Lynden Tribune)

Continued from 3

Ferndale. That’s across from the Phillips 66 ball fields. Visit whatcomoldsettlers.com for more information.

Each year, the celebration’s signature events are the parade and the car show, both held on Saturday. From 9 a.m. until 2 p.m. at Central Elementary School at 1st Avenue, there are always plenty of classic cars to enjoy.

At 11 a.m., the parade starts at 3rd Avenue, as folks parade down the avenue before they stop at Pioneer Park.

There’s more going on at the Old Settlers Picnic, with plenty of craft vendors and plenty of food to eat.

Visit whatcomoldsettlers. com for more information.

-- Contact Bill Helm at bill@ lyndentribune.com.

Continued from 4 mayor of Fairhaven in 1902. Mike did not adopt the twin boys, but he acted as the fatherlike role model for them. Mike was well-known in the area for being a hunter as he had stuffed animals hanging in his house. Because Robert’s mother had moved to Bellingham, Robert got the chance to grow up in the area, ride the cable cars and fish in the Salish Sea.

Robert met Opal Pitts, Lynda’s grandmother, and the two got married in 1926. Opal had lived on a farm in Mountain View Township in Whatcom County. She went to school in Ferndale and worked at a bakery.

Robert worked various jobs but was most proud of his restaurant. The building was an old interurban train coach that he remodeled. He named the restaurant Bob’s Holly Diner, which was located at the top of Holly Street in Bellingham. Locals enjoyed his fish and chips, which were made from a special batter. Eventually, the diner was moved to the old Highway 99 where Slater Road comes over I-5 across from the Red Barn. The couple would have a daughter named Evelyn, who is Lynda’s mother.

Evelyn graduated from Bellingham High School, and she married Lynda’s father, Clarence “Ed” Wilkinson. He was from Rhode Island and served in the Navy as a tail gunner for the B-52s. He eventually was stationed at Whidbey Island Naval Station, and he got orders to go to Corpus Christi, Texas and then to Alameda Naval Station in California. It was there that Lynda was born a Navy child. Ed would later serve in the Air Force, again as a tail gunner.

Lynda’s parents were at one point stationed in North Dakota when they received or-

Charlote Lee, top photo at left, was Lynda Lucas’s great-grandmother. Charlote arrived to the U.S. in 1902 with her two sons. Charlote’s twin sons Robert and Roy Griffin, top photo at right. Robert was Lynda’s grandfather, and Roy was her uncle. Robert later married Opal Pitts, Lynda’s grandmother. Robert Griffin remodeled this rail car, above, into a restaurant he called Bob’s Holly Diner.

Friday, July 28

11 a.m. Main gate opens

11 a.m. - 8 p.m. Registration opens Noon-6 p.m. Original log cabin

museums open

1-7 p.m. Kids pioneer corral by Larson Log Cabin

1-5 p.m. Kids pioneer passports by School House Cabin

Approximately 8:30 p.m.

Kogregation-Hot Air Balloon Glow, Pioneer Park open field area near ballpark

11 a.m. until dusk Craft and food vendors

Saturday, July 29

9 a.m. – 2 p.m. Pioneer Classic Car Show, Central School Grounds

1st Ave.

11 a.m. Pioneer Old Settlers Grand and Jr. parade, downtown Ferndale

11 a.m. Main gate opens

11 a.m. - 8 p.m. Registration opens Noon-6 p.m. Original log cabin museums open

1-7 p.m. Kids pioneer corral by Larson Log Cabin 1-5 p.m. Kids pioneer passports by School House Cabin

11 a.m. until dusk Craft and food vendors

Whatcom Genealogical Society’s Family History Exploration and book sale inside Pioneer Pavilion Community Center across from registration log cabin.

Since 1967 L FS Marine & Outdoor has served the Pacific Northwest community. Now, with several stores in Western Washington and Alaska , L FS maintains its roots in W hatcom County with our flagship store and corporate office at Squalicum Harbor in Bellingham. T he secret to our 50+ year success story has been dependable and reliable ser vice through the most challenging times We understand that our customers rely on us to help them navigate a successful boating and outdoor experience. T hat is why we’re here for you , and that is why we’re here to stay.

ders to move back to Beale Air Force Base in California. This created a split in Lynda’s high school year, so she was given the chance to do her final year of high school at her mother’s alma mater. From her memorable childhood experiences picking strawberries and raspberries on the farms in Bellingham, she decided Bellingham High would be a good fit, and she would get the chance to live with her grandma Opal for that year as well. What was unique about her high school was that she was the class of ’67, which was the last class of the high school since the following year was when Sehome High School opened.

Lynda’s father retired from the service after more than two dozen years, and Ed and Evelyn moved back to Whatcom County and found their home in Ferndale.

Making her own footprints

Lynda later moved back to North Dakota, and it was there that she met her husband, another service man. The two traveled a lot but eventually found their way back home in Ferndale where they welcomed a boy into the world. Lynda has been in the area since 1973.

She owned Precious Petals Flower Shop for 22 years. Her father died, and one of his wishes was that Lynda would attend college. So, Lynda sold the business and enrolled at

A Bellingham High School graduate, Evelyn Griffin married a service man named Clarence “Ed” Wilkinson. Ed was in the Navy and Air Force as a tail gunner. They had a child, Lynda Lucas. (Photo courtesy Lynda Lucas)

Western Washington University where she obtained an education degree, a special education degree and an art degree. She joined the staff at Skyline Elementary and has been retired for 10 years. Lynda has been a trustee of the Old Settlers Association for 23 years, and she did not want to go anywhere else because home was home.

“When you look at family history, you go where your family is from, and my mom is

from Bellingham. My grandpa was basically here. My grandma lived here. And so that’s what I did. My love is waking up, coming down, getting coffee and seeing Mount Baker,” Lynda said. “Who would not want to live here? We’ve got a great community. People are super nice … We live in such a precious area to be able to explore anything we want to, and so that’s why I stayed here.”

While Lynda has served with the Old Settlers Association, there have been ups and downs. As exciting as it is to share the history of pioneering families, there’s concern for the length of time the event will be held, particularly due to a lack of volunteers.

“My value is that this organization needs to stay alive. I want to make sure we stay alive and do what our mission was. And that was to perpetuate an annual celebration for down here at the park and for the community of Whatcom County, not just Ferndale. A lot of people think it’s just Ferndale. It’s not. Pioneers were from every place, not just Ferndale,” she said. “Our sister group, the Heritage Society, does an absolutely astonishing job with inside the cabinets and taking care of the artifacts and doing the garden beds. It’s a team effort for what we do.”

According to Lynda, orga-

nizations across the nation struggle to find younger people interested in volunteering. In addition, Ferndale doesn’t have a lot of people who have pioneer families, and of those who do, they are slowly dying.

“How does this stay alive? How can we have some individuals who hold that interests who want to make sure that there is a 130th, 140th annual grand parade?” she said.

To be able to offer a yearly event to the public, Lynda said it can’t be done without volunteers, which is why between 50-75 people are needed to help the annual parade take place. She said the association doesn’t have many pioneer families because they think they can’t be a pioneer family. Lynda encourages them to become young pioneers and to be proud of their family heritage, no matter what country their family immigrated from.

“If you want to be a member, come on, we would love to have you as a trustee,” she said. “But if not, be a proud volunteer to put this event on.”

Lynda and her family’s story would not have existed if it weren’t for Capt. John Crowell’s journey to Bellingham and the events that followed. Lynda is appreciative of the hard work and countless hours she and members of the association have put in to run the event each year and share the pioneer history with locals.

“It’s a job to me. I’m proud of the job that we do here. But it’s also a learning experience,” Lynda said. “I have learned so much. If I was in college class, I don’t know if I could have learned as much as I have with doing this. I share that with other people and organizations. If I can help, I will, and that’s what I want to do. My learning is their learning as well. Ask me, and I’ll give the answer. And if I don’t know, we’ll figure it out.”

-- Contact Taras McCurdie at taras@lyndentribune.com.

The Lynden Tribune and Ferndale Record asked its readers to submit stories of loved ones who were Whatcom County pioneers. This story is one of three we received from our readers. Each of the three stories are in this publication.

Thomas ‘Gabe’ Carman was born in 1899 to Israel and Kate Bulmer Carman in Nooksack. Israel came to Whatcom County about 1875 from Iowa and Kate came about 1880 from Wales, England. Gabe’s parents lived and worked in the Sumas, Nooksack and Maple Falls areas. Israel was a carpenter and auctioneer. He worked for the Great Northern Railway building depots and hotels.

When Gabe was a toddler, his parents operated a boarding house in Maple Falls which is where he got his nickname of Gabe. The boarders called him Gabriel because he woke them up so early in the morning.

Viola came to Everson with her parents, Robert and Eva Stump, from Oklahoma in 1912. Her parents lived

and worked in the Everson Bellingham areas. Robert was a carpenter and built several homes in the EversonNooksack area. He also worked for the milk condensary that was in Everson.

Both Gabe and Viola attended Nooksack High School in Nooksack. They now have had five generations who have attended Nooksack Valley High School.

Viola worked at the Rochdale store in Nooksack before they were married. Gabe had purchased a farm north of Nooksack. Gabe built a home from a single log which he cut and had milled into lumber and they lived there and worked the farm until retirement when they moved to Bellingham for their last 10 years.

They had two daughters, Ardis Carman Bunker and Joyce Carman

Heutink who still reside in Whatcom County.

Gabe purchased his first car in 1921 from the OK Garage in Sumas for $600. He had to pay an extra $7 to get a steering wheel.

Gabe was an air raid warden during World War II. Viola worked out to help the family finances, several years at Hilda’s Shoprite and Kale Canning Company in Everson. Kale’s became a family job with Viola in the office, Gabe occasionally there, both daughters and then their grandchildren.

Gabe passed away at 104 and Viola at 99. They had a long successful and happy life in Whatcom County, living in three generations was Gabe’s ambition and he made it with three years to spare.

During the 1850s, Bellingham Bay and its surrounding area were being discovered by the first white settlers who saw opportunity in the coastal waters and dense inland forests.

In December 1852 Henry Roeder and Rus-

sell Peabody had arrived at the mouth of Whatcom Creek to establish a saw mill on the waterfalls there. The townsites of Whatcom and Sehome were being platted.

“By 1858, there were two coal mines and a saw mill operating on the bay, and during the year thousands of gold seekers passed through the bay and some stayed to settle in the outlying

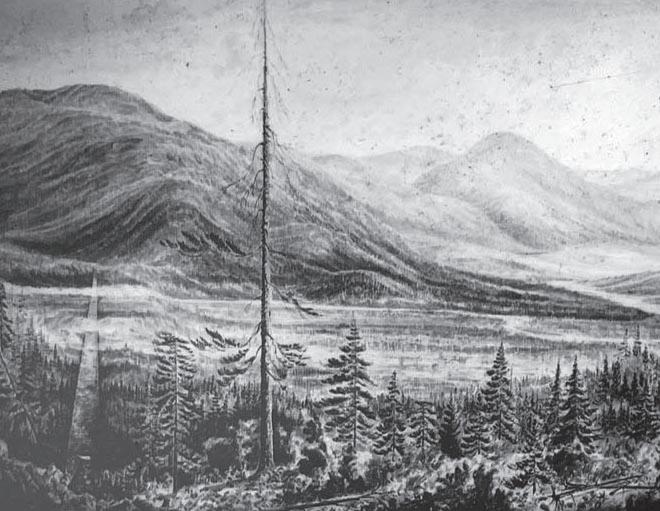

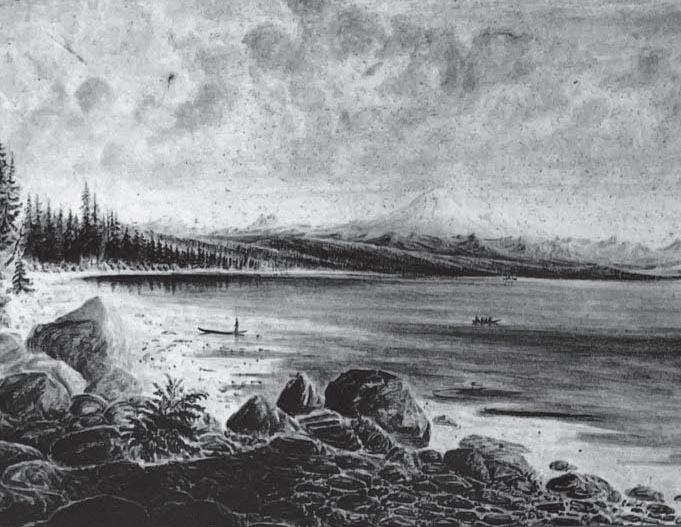

While the Americans used a watercolor painter to record the survey’s scenes, the British used photography that was in its infancy. (Courtesy photo)

It was said of Henry Custer, chief topographer, that no one did more for the American effort than he. He was the first to check out rivers, valleys and trails along the boundary route. (Courtesy photo)

areas of the county,” reports the Whatcom Then and Now book of Wes Gannaway and Kent Holsather.

The eager prospectors were headed to the lower reaches of the Fraser River in search of gold glitter. They needed a way to get there, and the Whatcom, or DeLacy, Trail opened at a diagonal toward present-day Everson and on up past Sumas into the Fraser country.

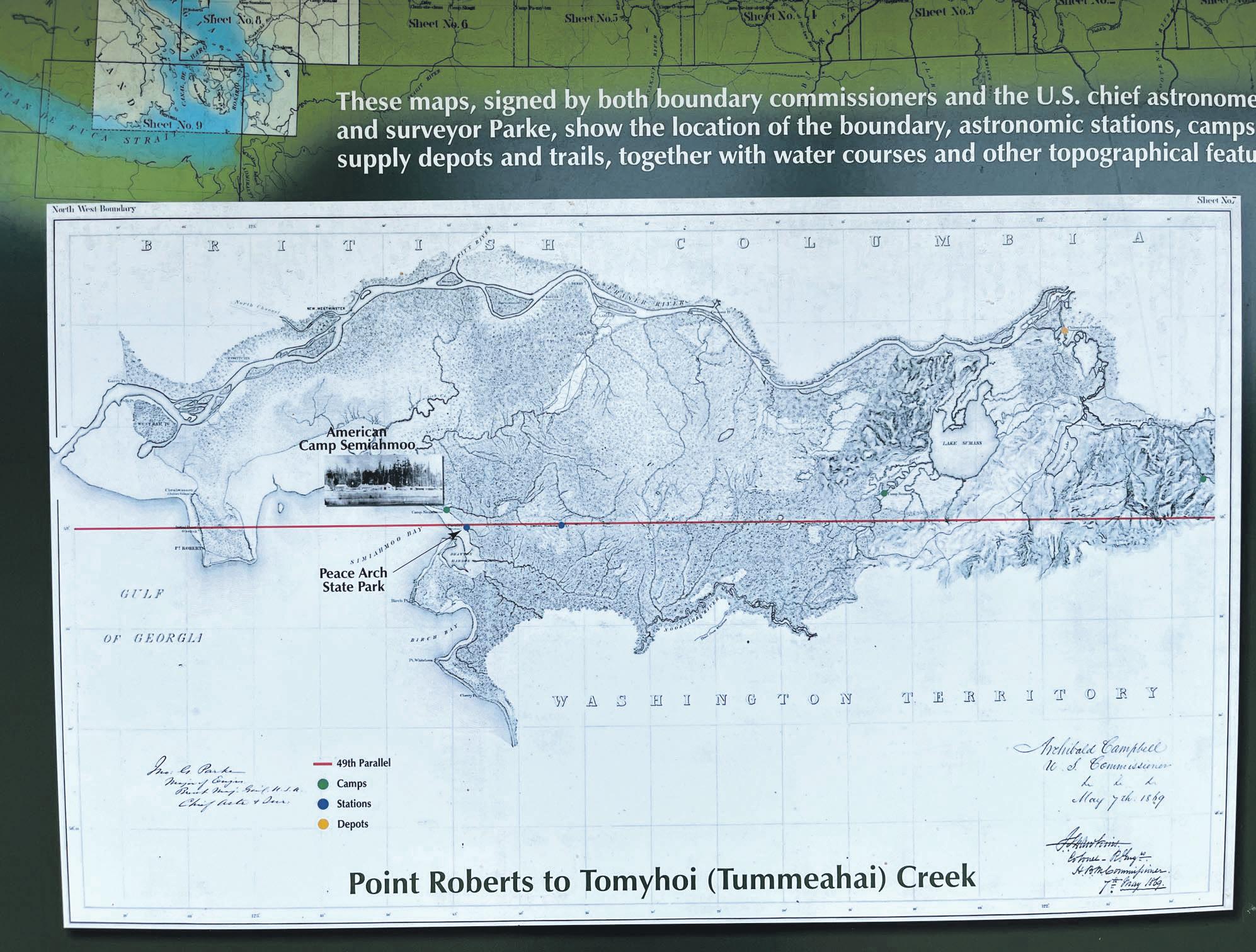

And the northern boundary of Whatcom County, Washington Territory and the United States was being marked out for the first time from the uncharted wilderness.

Finally settling on the line Dispute had simmered for

decades about what would be the border between the British Columbia region and the Western settlement of the United States. Finally, in 1846, the U.S. and Britain (functioning largely through the powerful Hudson’s Bay Company) settled on the 49th parallel all the way to the water channel between the mainland and Vancouver’s island. It took another 10 years for Congress to get around to appointing those who would actually do the job of marking the border, on the ground with surveying gear and astronomical instruments.

Actually, there were two commissions for the task, one from each country. They were supposed to cooperate, and

mostly did at the workingman’s level, although the heads of the two boundary survey groups notoriously did not. The chief astronomer and surveyor for the British, Sir George Henry Richards, said of the American commissioner, Archibald Campbell, that he was “impossible to deal with unless given everything he wants,” reports a covered display on the boundary survey at Peace Arch State Park in Blaine.

“Recognizing the importance of this endeavor, both countries sent their most accomplished surveyors, astronomers and support people to perform this task,” states a Peace Arch panel about seven key leaders on each side. “Us-

ing the most advanced surveying equipment and methods, they did a remarkable job, establishing 161 monuments and the 410 miles surveyed by the commissions between 1857 and 1862.”

As well, they were to pinpoint where the water boundary between the U.S. and Britain lay. The language of the Treaty of 1846 turned out to be vague. The Americans’ Campbell insisted that the “main channel” was today’s westerly Haro Strait while the Royal Navy’s head men said it was Rosario Strait more to the east.

Because this was left unsettled, the Pig War played

Continued from 11

out in 1859 on San Juan Island. Triggered by the shooting of a Hudson’s Bay Company pig by an American settler, this flare-up brought both Yankee and British forces onto the island in encampments a few miles apart. Recreations of these camps can be visited today. (A Germanled arbitration in 1872 confirmed Haro Strait as the water border.)

The American contingent for land surveying arrived first on site in June 1857. Their base was Camp Semiahmoo on what is now the Canadian side of the bor-

der, about where White Rock, B.C. is. The British worked from Esquimalt on Vancouver Island.

“While it would be nice to say that they worked together, in truth they rarely saw each other. The surveyors and astronomers of each commission leap frogged one another from one section of the boundary to the next,” states a Peace Arch panel.

Not every mile was cut and cleared to mark the 49th parallel. That would be too expensive, the Americans said. What was agreed on is that the boundary would be “marked

Sir George Henry Richards, below, was the British contingent’s chief astronomer and surveyor. Dr. Caleb Burwell Rowan Kennerly was a surgeon and naturalist on the American team. He reportedly married an indigenous woman while at Semiahmoo and their descendants include the Kinleys of Lummi Reservation today. (Courtesy photo)

where it crosses streams of any size, permanent trails or any striking natural features.”

Another difference in methods was that the U.S. effort went only to the summit of the Rocky Mountains while the British went farther to the mountains’ eastern base.

Each group established their own stone monuments, or cairns, at points including the summit of the Rocky Mountains. It’s interesting to note that these of each party differed

by only 38 feet at the mountains’ summit, entailing a give-and-take of only 19 feet.

...

The New York Times in 2011 published a story on the “not-sostraight” demarcation of the U.S.-Canada border.

Zoom in close using today’s satellite technology, it turns out the line is not very straight and it hardly stays right on the 49th parallel.

“Marked by a 20-foot strip of clear-cut forest,

the border may seem straight as a ruler. But as it zigzags from the first to the last of the 912 boundary monuments erected by the original surveyors [counting in from the Rocky Mountains to Lake of the Woods, Minnesota], it deviates from the 49th parallel by up to several hundred feet,” the Times reported.

The task at the time certainly involved hardship and heroism by those who did it, as they lacked roads, electricity and the digital precision

of today. In fact, the original markers “seem actively to avoid the line, straying as much as 575 feet north and 784 feet south of the line.”

“In all its imperfections, this border is a monument to the power of mind

$200,000 for supplies, provisions, transportation and accommodations, reports the book A Line of Blood and Dirt by Benjamin Hoy.

How about these orders of staples?

966 pounds of hard bread, 645 pounds

advantage of the men’s helplessness as they crossed difficult terrain. Tired from long treks and limited diets, laborers looked for simple pleasures. They delayed marches, for example, at every opportunity to gorge themselves

sleighs and a wide array of food.

“They piloted steamers, ferried parties across the Chilliwack River, cared for animals, rented out their cabins, and served as guides. Most of all, they provided crucial information

mission, said the indigenous people he worked with possessed “the most minute topographi-

cal detail” of the territory that was now being bisected and bounded by a contrived political line.

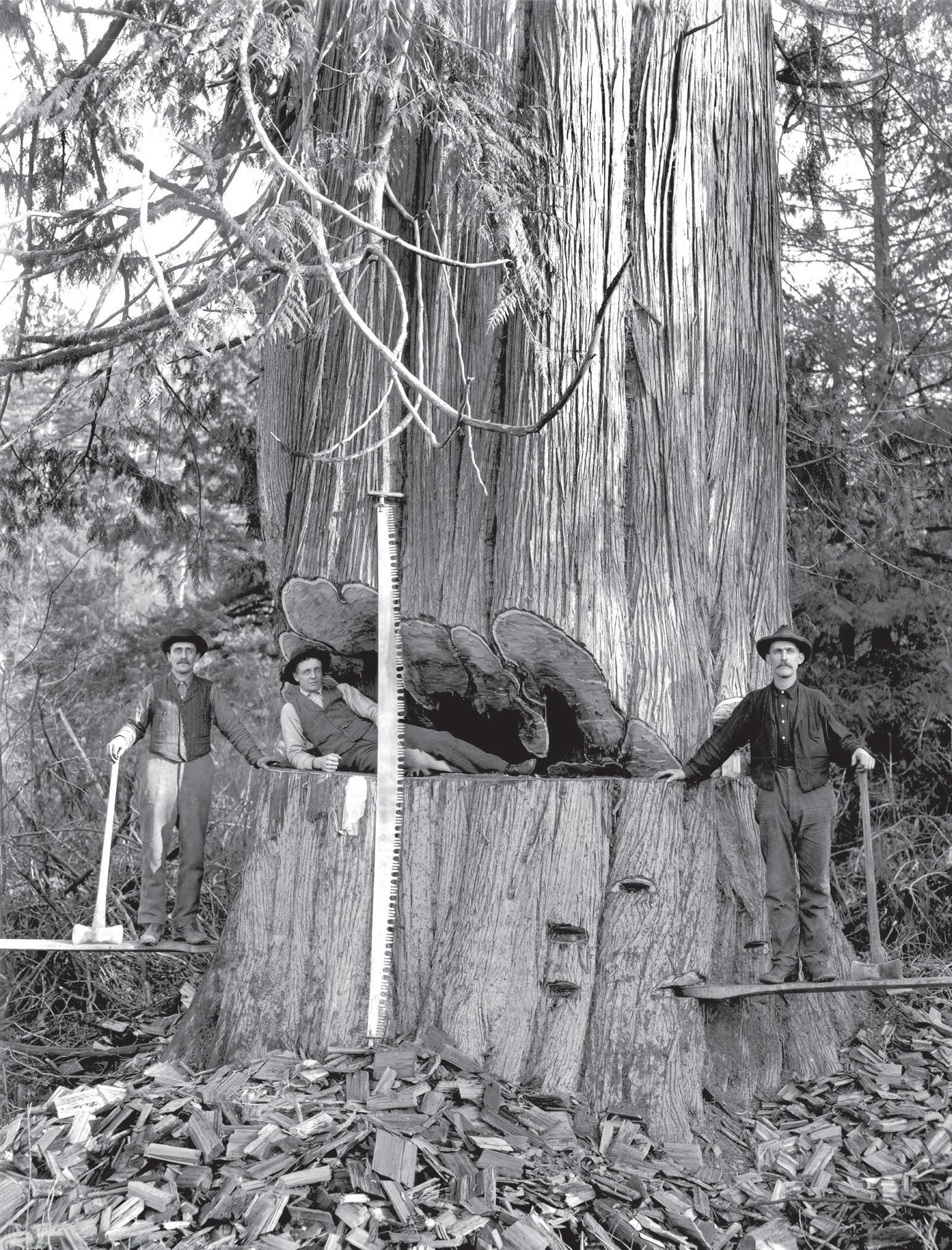

All photos courtesy Darius and Tabitha Kinsey Collection, Whatcom Museum, Bellingham, WA

By Elisa Claassen For the Tribuneith their cameras, Darius and Tabitha Kinsey introduced the Pacific Northwest and its lifestyle to the world.

The husband and wife worked together to create memorable images of logging, big forests, railroads. These images, according to Whatcom Museum of History and Art’s website, weren’t meant to be art “but to record people, places and industries.”

The Nooksack Cemetery is on the hillside adjacent to the Nooksack Elementary School where East Madison Road turns into Breckenridge Road. Upon entering under the arch, the oldest section lies to the left. Names such as the Everson family and Bergs.

Jim Berg, a more recent historian of the family who passed away in 2020, was a regular participant both in providing historical information to the Lynden Tribune as well as presentations as host of NookChat, a partnership of the Nooksack Valley Heritage Center

and the Everson McBeath Community Library.

WThose programs can be viewed online at YouTube and at washingtonruralheritage.org.

‘So adept’

According to an article in the Seattle Times on June 14, 1953, the Rev. Erle Howell of First Methodist Church spoke of the Kinseys by looking at Darius coming to Washington from Missouri in 1889. Darius had set up a portrait shop in Sedro Woolley. However, he wanted to go out into the world where the action was. So he photographed loggers and railroad workers in action.

Darius married Tabitha Mae Pritts of Nooksack in 1895. The two met at her parents’ homestead in Nooksack.

While shooting photographs in Skagit and Whatcom counties, Darius taught Tabitha to process his photographs in the darkroom back home.

Darius continued to travel and send work back to Tabitha, who then sold and shipped the prints. According to Howell, Tabitha became so adept with advances in photography that her husband would permit

Darius and Tabitha Kinsey were a husband-and-wife photographic team. Darius shot the photos, Tabitha printed the photos in the darkroom. Their partnership began here in Whatcom County when Darius, an itinerant photographer, first met thenTabitha Pritts at her family’s Nooksack homestead.

no hired helper to apply color to his finished prints.

In 1907, the Kinseys moved to Seattle where they bought a large house to serve as

a home and studio. The family had two children, Dorothea and Darius Jr., and the household had a housekeeper and a studio helper so “her time could be given to finishing and shipping prints,” according to her

daughter. “The packages often were so heavy that mother could not board the streetcar or lift them to the counter at the express office without aid.” For the business to work, Tabitha sacrificed her social life to

help her husband. In the oversized “Kinsey, Photographer” coffee table book from 1982, the first volume focuses on the Darius and Tabitha’s earlier work and includes conversations with their children. Dorothea, whose married name was Parcheski, was interviewed in Seattle in 1973 for the coffee table book. When their parents met, her mother was engaged to a railroad conductor on a train that Darius often took. Said Dorthea, Darius and Tabitha lived a life of partnership.

“Mother’s devotion to my father, whom she always called Dee, was outstanding, and I admired her for it,” she stated. “In later years, I began to understand that father never could have accomplished what he did without mother’s loyal support

and hard work. But I do not think father ever had any intimations of his own greatness as a photographer. He never did mention anything that led me to believe this. Neither did mother. They merely pooled their abilities and resourcefulness and together created something of great historical value. And it was a partnership setup to the Nth degree.”

The Kinseys were firm in their faith and did not work on Sunday, mountaineers capable of climbing Mount Baker and Mount Rainier and perfectionists with their work.

“Father was a stickler for thorough work,” Dorothea (Kinsey) Parcheski in an interview with Rev. Howell. “He insisted that each print be washed 16 times to prevent it from turning

yellow. Washing prints was such drudgery that I dreaded it, but it paid off. Last summer while visiting an aged couple

on Hood Canal, I saw some of father’s photographs hanging on the wall, still untarnished with age.”

In the Seattle years, one home the family lived in had a second

Continued from 17

floor that they used as a darkroom. Darius worked there until his death in 1945. Jesse Ebert secured the collection, consisting of glass plates and negatives showing 50 years of Pacific Northwest logging operations. Ebert cared for the collection for 25 years before he sold it to Dave Bohn and Rodolfo Petschek who published a two-volume book about the Kinseys’ photography. The work became popular during their lifetime and has continued through today. Much of the existing collection is at the Whatcom Museum of History and Art.

Staying power

Writer John M. Harris, on the journalism faculty at Western Washington University (WWU), researched and wrote about the Kinseys for the Seattle Times magazine section in January 2023. Harris wrote that the Whatcom Museum, through long-time staff photo archivist Jeff Jewell, continues to scan the images and sell them to commercial clients for $1 per megabyte. American filmmaker Ken Burns paid about $6,000 for the images’ use in two of his documentaries.

Designer Ralph Lauren’s company paid about the same, Harris wrote, for Kinsey images for his stories in London and Milan. The University of Washington has a 12-foot by 14-foot print that serves as a backdrop for maps, documents and other Kinsey photos to show forests of South Puget Sound. Bohn and Petschek included locomotive essays by John T. Labbe in a 1984 Chronicle Books piece focused on Kinsey train photography. Each type of train had a story and a purpose. Bill Pulver of Bellingham was

Three Lumberjacks, c. 1920. Through a 50-year career in photography, the couple created images that captured the character of the early Northwest. More than a simple documentary record, Darius’ meticulous compositions communicated the monumental interaction between men, machinery, and mammoth trees. At the time of his death in 1945, some 4,500 of Darius Kinsey’s original negatives remained – a collection that, since 1978, has had a permanent home at the Whatcom Museum.

interviewed for a segment.

“The valves were underneath the car so you had to step over the rail to set them up,” Pulver stated. “Then, when you got to the bottom of the hill you moved along the car and you’d step over the rail, underneath the car, more or less, and take the valves down, and then you’d trot back up to the next car that came by, and so forth. It was dangerous, in a way, because nobody could see you. If the train was on a curve you were just there by yourself, and the only way they could tell if something happened to you is that they wouldn’t be able to pull the train pretty quick because there would be nobody knocking the retainers down.”

Whatcom Museum website, more than 4,700 negatives and 600 prints make up a valuable Northwest legacy “whose fame has reached as far as Europe and Japan.”

Archivist Jeff Jewell said the Kinseys disposed of approximately 10,000 negatives as they sorted through to see what was more marketable. The Kinseys were in business and needed to have resale value, he said. The photographs were published, Jewell said, in many historical reference books, used on the covers of novels, shown in the Museum of Modern Art in New York and exhibited in the company of some of America’s greatest photographers such as Timothy O’Sullivan, William Henry Jackson and Eadweard Muybridge.

woods as the great cathedral; the feathery grain of tree bark, dappled forest light, the sheen on a locomotive and the grime on a logger’s (expletive deleted) are all visible in amazing detail.”

Darius lived an adventurous life “dodging avalanches, crossing crevasses and jumping over rattlesnakes. On family outings, he was known to jump out of the car on a moment’s notice, set up his equipment on the shoulder of the road or disappear up a trail.”

For more details and to see a virtual exhibit, see whatcommuseum. org/virtual_exhibit/ universal_exhibit/vex3/ index.htm.

Note: The author’s parents, maternal great grandparents, and other family are bur

etery in Nooksack. The Kinseys are buried near the Berg family which has a large distinctive monument. While many readers grew up hearing the name Tabitha on a popular 1970s TV show, “Bewitched,” this Tabitha was pronounced differently per Jeff Jewell:

Berg called her Aunt Tibs. Photos are still being found and sometimes now the families wish to keep the originals and have the museum scan them for posterity. From 1-6 p.m. Wednesdays, Thursdays and Fridays, Whatcom Museum’s photo archives are open for research.

Photo courtesy Darius and Tabitha Kinsey Collection, Whatcom Museum, Bellingham, WA

Whatcom Museum

Photo courtesy Darius and Tabitha Kinsey Collection, Whatcom Museum, Bellingham, WA

Whatcom Museum

Pioneer Beer Garden ………………............................. Steven Rauch

Pioneer Classic Car Show ………...............……….. Susan Anderson

Kids Pioneer Corral Entertainment ……........………….. Jackie King

Vendors ………………....................................................... Jackie King

Children’s Pioneer Passport Hunt …………...…….. Pauline Zender

Stage Entertainment ……………..............................….. Lynda Lucas

Program Roster, Advertising, Posters …...…………….. Lynda Lucas

Registration …………........ Jody Johnson, Jackie King, Lynda Lucas

Signs ……………….................... Al Gitts, Steve Leibrant, Don Imhof

Sponsorships ……..........................................………….. Lynda Lucas

Facebook …………….................................................….. Lynda Lucas

Volunteers ………………...................................... Yvonne Goldsmith

New Stage Construction …..... Honorary Trustee Howard Vroman

Media Advertising ……………..................................….. Lynda Lucas

Grand Parade ………………............................... Volunteers: Bertella

Hansen & Nancy Knapp; Trustees: Mollie Gandy & Lynda Lucas

Jr. Parade ……………….................... Pauline Zender, Kathie Howell

Construction ……………..................….. Steve Leibrant, Don Imhof

Stage Set Up …………..........................................……... Jon Mutchler

Publication, Poster Editing & Assistant …....…………….. Ben Hines

Cabin Curators ………………................... Ferndale Heritage Society

Ardis Bunker and Joyce Heutink are sisters who have lived in Whatcom County for more than 90 years.

They are the daughters of Thomas and Viola Carman.

Joyce and Ardis were born and raised on the family farm one-half mile south of Nooksack Valley High School.

Joyce married her high school sweetheart Harold Heutink. They lived in Everson and raised three children before moving to Lynden. Ardis married Lloyd Bunker

and they lived in Nooksack while raising their three children before moving to Bellingham. The sisters have memories of different times as they grew up. A lot more snow in the winter than we get now, no electricity and no telephone, no indoor plumbing are a few of the memories that really stand out. Joyce and Ardis appreciate the conveniences they have today.

Ardis worked as a school secretary for the Nooksack Valley School District for 25 years. Joyce worked for the Whatcom Counseling Clinic in medical records.

Lloyd and Evelyn Van Boven moved to Whatcom County from Emmons County, ND in 1946. To get to Lynden, the Van Bovens traveled by train with their baby, Alan.

Lloyd was not interested in farming, so he looked for job opportunities after serving in WWII. Two of Evelyn’s uncles lived in Lynden: Herman Haveman and Pete Hollaar.

Lloyd and Evelyn had 11 more children, and raised them in Everson on Hampton Road.

The following is from a story that appeared in the Lynden

Tribune in 1985. The story is titled, “Lloyd Van Boven works in same building for 39 years.”

Lloyd Van Boven’s work routine is well established. For 39 years now, he’s been working at 500 Front St.

During his long career on Front Street he has worked for two different employers: Farmers Mercantile, and DeWaard and Bode Inc. DeWaard and Bode Inc. moved their appliance store to Front Street 20 years ago.

He began working for Farmers Mercantile shortly after he moved here from [the Dakotas] and when the building was sold to Jake DeWaard and Eugene (Rube) Bode 18 years later, he just stayed on and learned to sell

hardware and appliances. Now, Lloyd is 65 and ready to slow down. He plans on only working part-time. After selling to the public for 39 years he’ll miss the people, but retirement is appealing too, he said.

“When most people retire they say they’re going to travel, but I don’t have any plans,” Lloyd said. “I have 20 acres and enjoy chopping wood, so I guess I’ll do that. I’m 65, but I don’t feel like it.”

The story’s author, Renae Erickson, said that her sister, Jean Taylor-Byers, retired on July 7 from Lynden’s Public Works Department after 33 years. Taylor-Byers has no plans to travel. She also has no plans to chop wood.