SPECIAL EDITION

CELEBRATING FIVE DECADES OF MUSIC AND CULTURE

Hip hop is so much more than just music: it’s an art form, a way of life and a global cultural force. Since its inception in the Bronx in the 1970s, where the likes of DJ Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash pioneered the sound, hip hop has transcended borders through fashion, culture and its four pillars: DJing, rapping, graffiti and breakdancing.

In the UK, venues like Subterania, Fridge Brixton, Bar Rumba, Rock City, Hammersmith Palais, SW1 and Labatt’s Apollo helped shape the UK scene, as did the spot outside the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden where breakers congregated to show their latest moves. Icons like London Posse, Outlaw Posse, Slick Rick, Cookie Crew, Monie Love, Klashnekoff, Killa Kela, TY, Sway, Kano, Skinnyman, Akala and Blak Twang all contributed to the musical richness, laying the foundations for a new generation of trailblazers to innovate the British sound.

While this magazine celebrates 50 years of hip hop, it also serves as a reminder of the importance of supporting all levels of musical talent, from grassroots artists through to world-leading stars. Hip hop's enduring influence on today's music industry underscores its vital role in shaping and propelling musical innovation.

Here's to hip hop — a testament to music's transformative and unifying power.

Michelle Escoffery, President of PRS Members’ Council

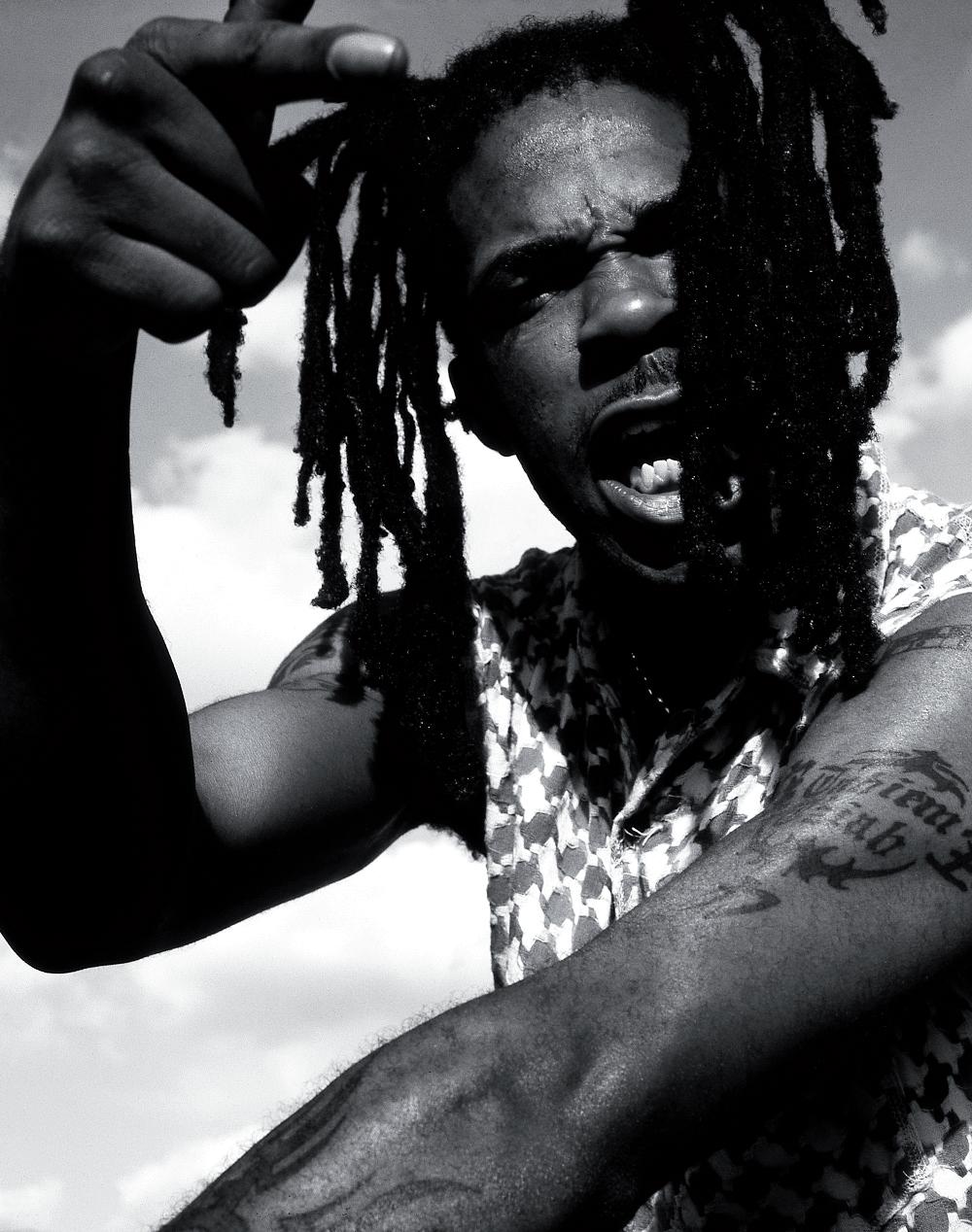

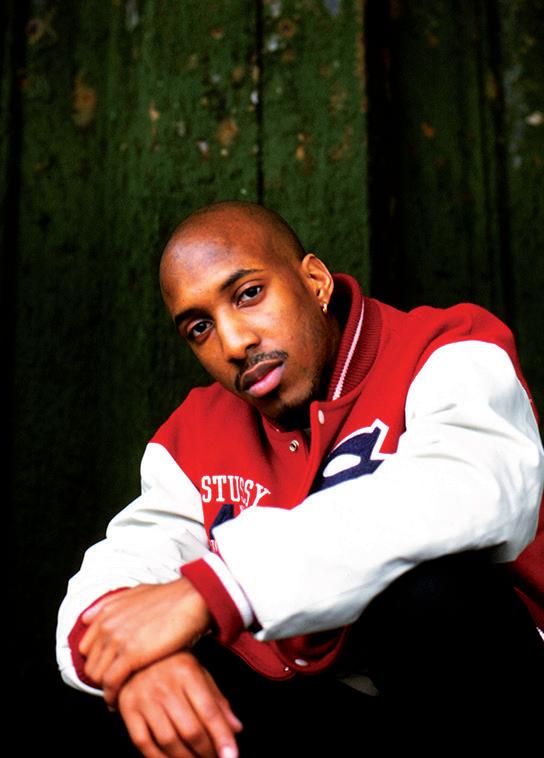

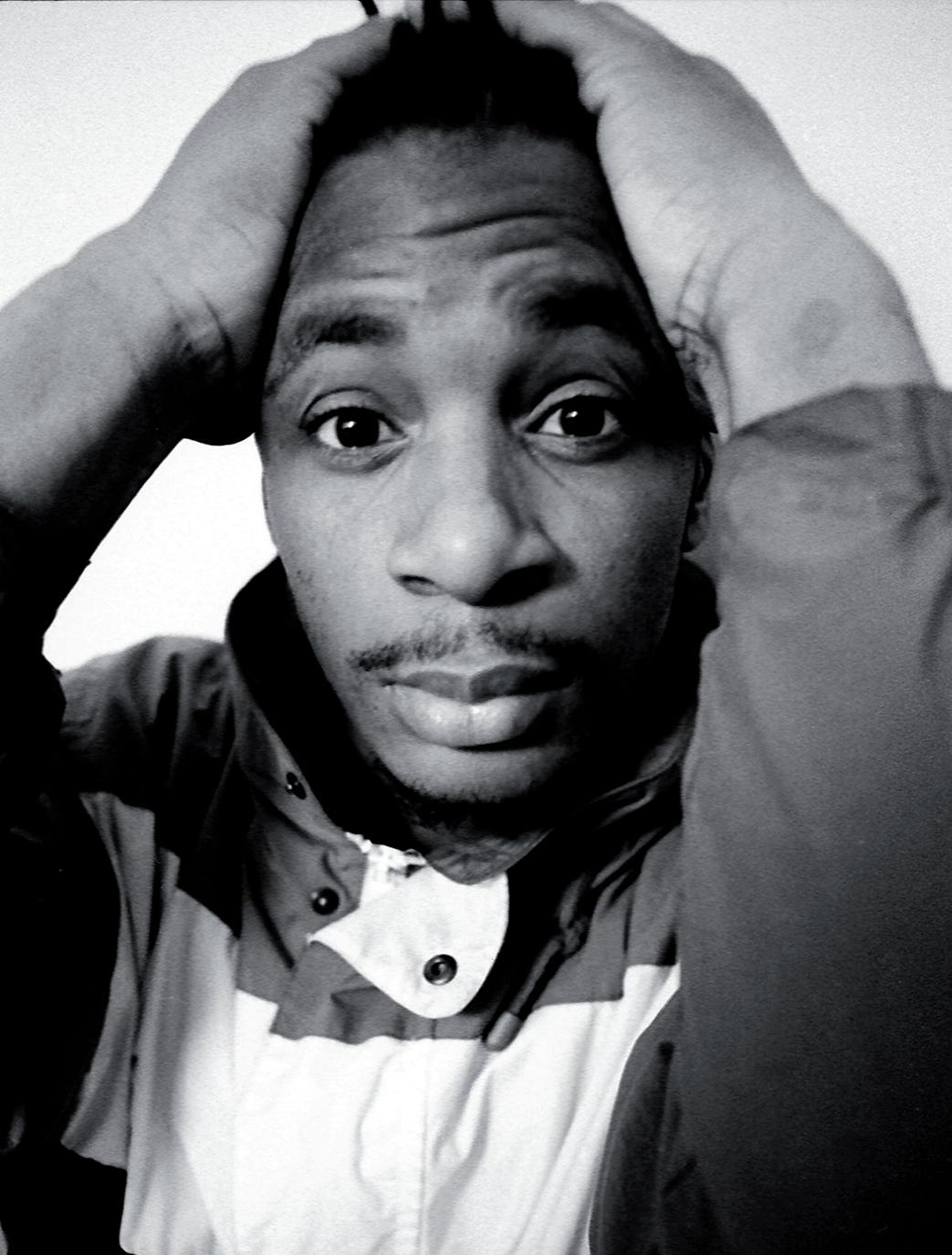

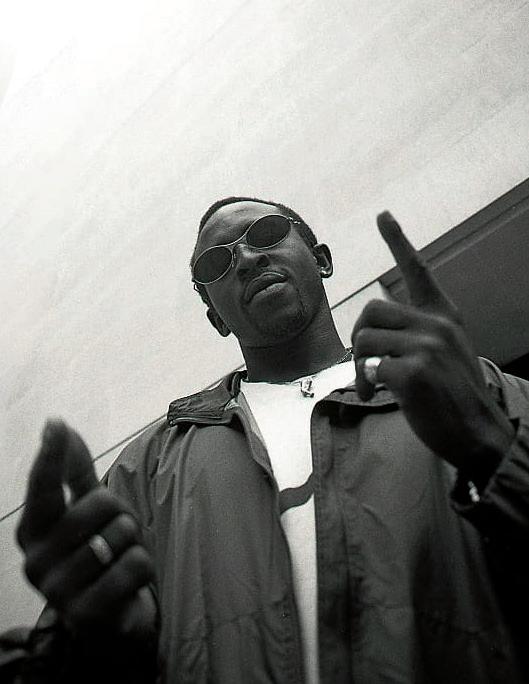

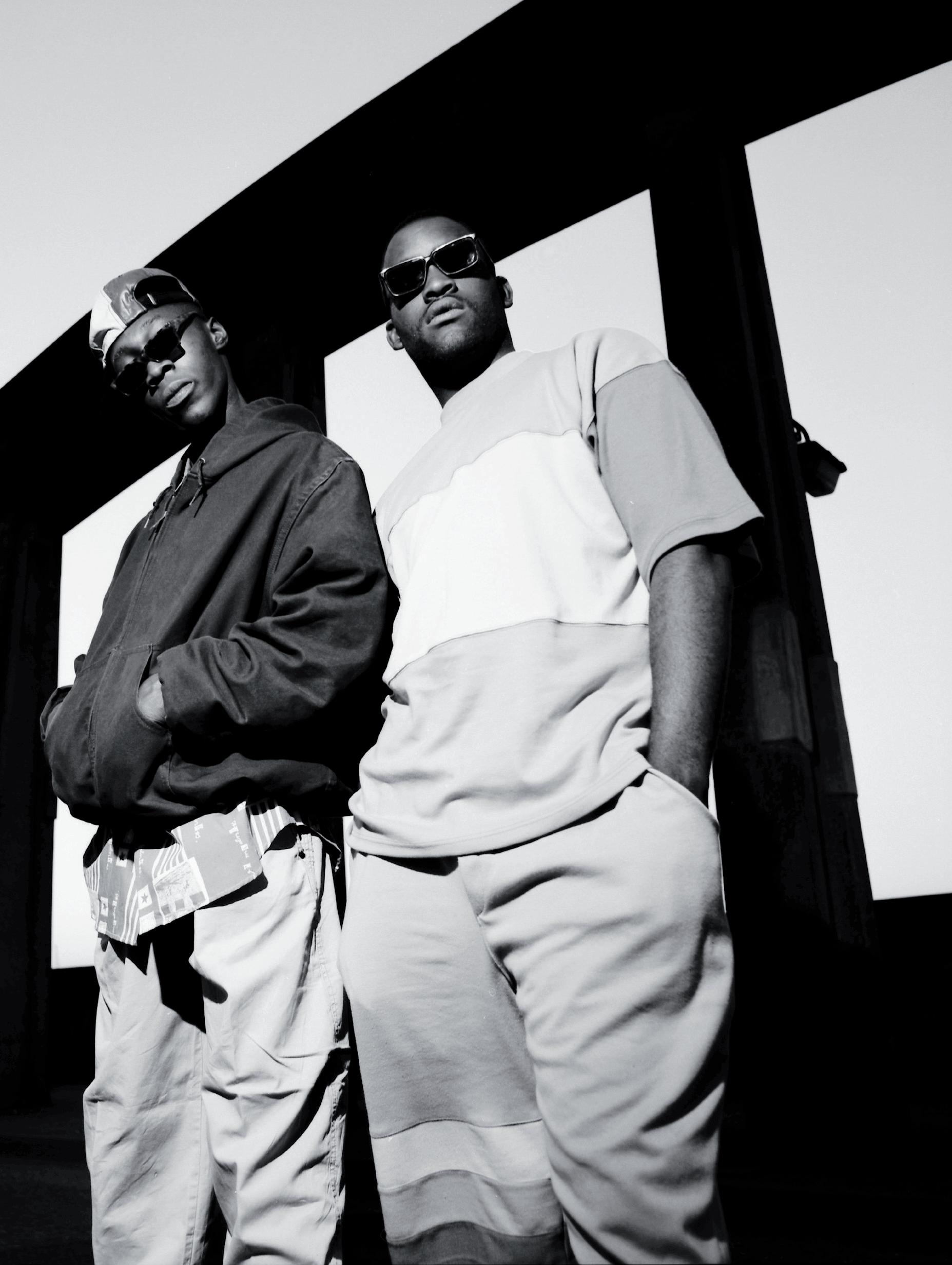

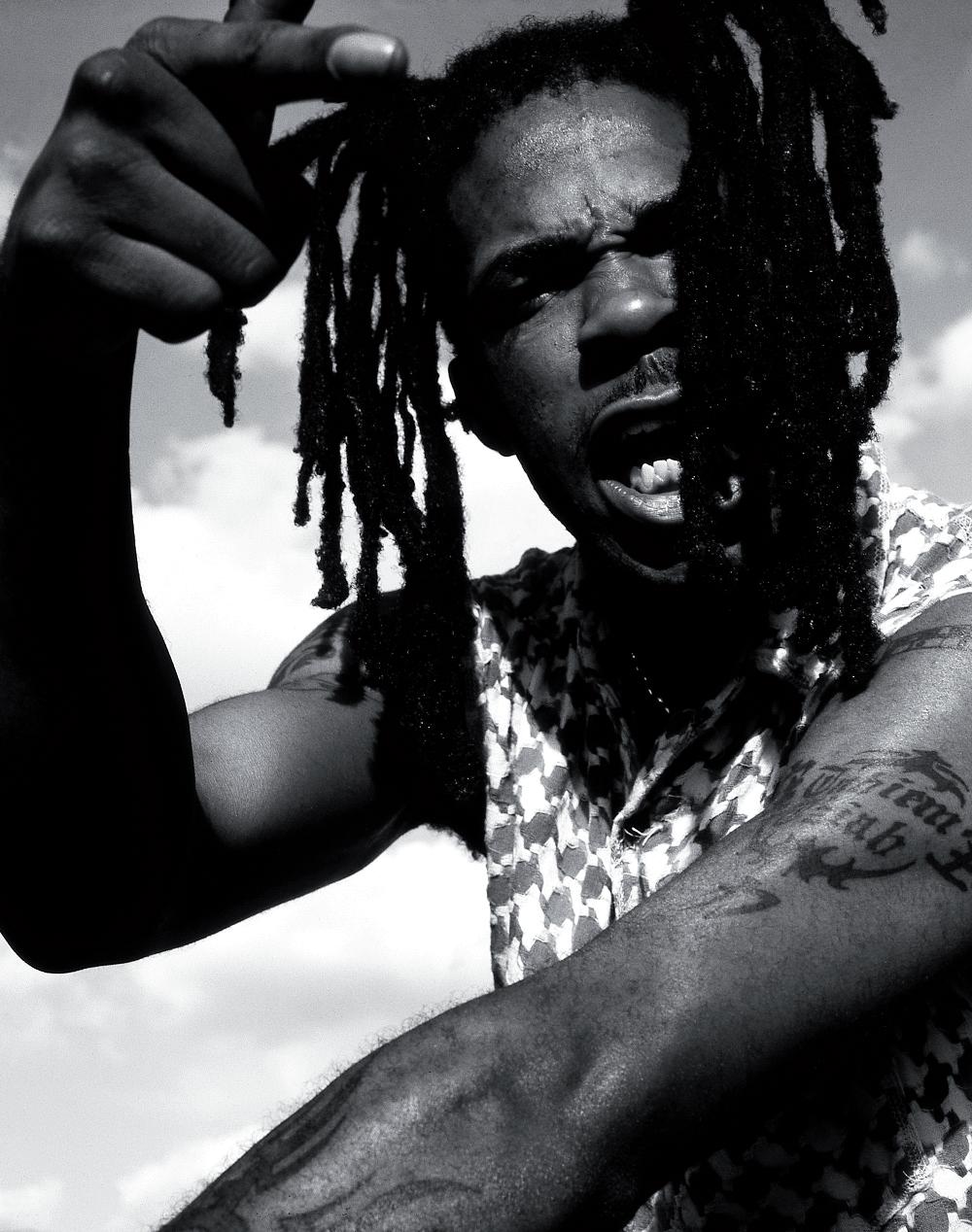

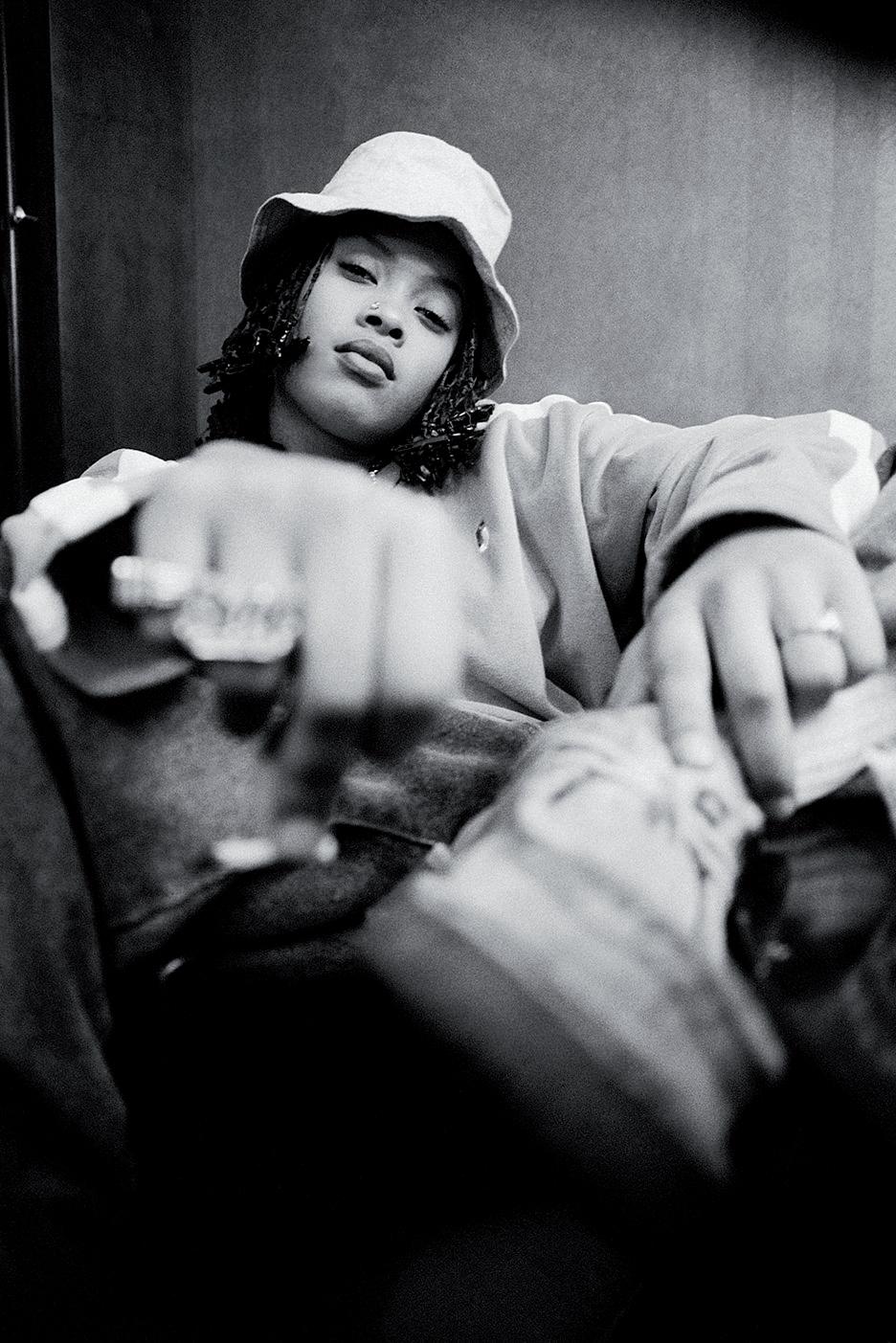

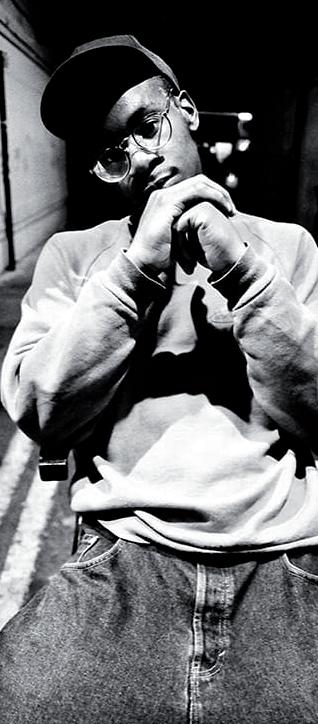

Blak Twang

The groundbreaking groups of UK hip hop

The lyrical genius of UK hip hop

Breaking down barriers as a female hip hop artist

MF DOOM

Tee Max — hip hop’s visual historian

The radical resistant roots of UK hip hop

PRS Foundation — powering up UK hip hop

Hip hop — a force for personal growth

ENNY

How radio DJs shaped hip hop

Producers — the beating heart of hip hop

Hip hop’s sampling legacy

Slick Rick

Under the influence — UK genres that owe a debt to hip hop

The evolution of the hip hop hook P

Contents

Money Hip hop entrepreneurs TY — in memoriam 4 6 10 16 18 22 28 32 36 38 40 42 46 48 50 54 56 60 62

Editor Maya Radcliffe

Content Editor Sam Harteam Moore

Art Director Carl English

Creative Manager Paul Nichols

Contact magazine@prsformusic.com

ISSN 0309-0019© PRS for Music 2023. All rights reserved. The views expressed in M are not necessarily those of PRS for Music, nor of the editorial team. PRS for Music accepts no responsibility for the views expressed by contributors to M, nor for unsolicited manuscripts, photographs or illustrations, nor for errors in contributed articles. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission is strictly prohibited.

6

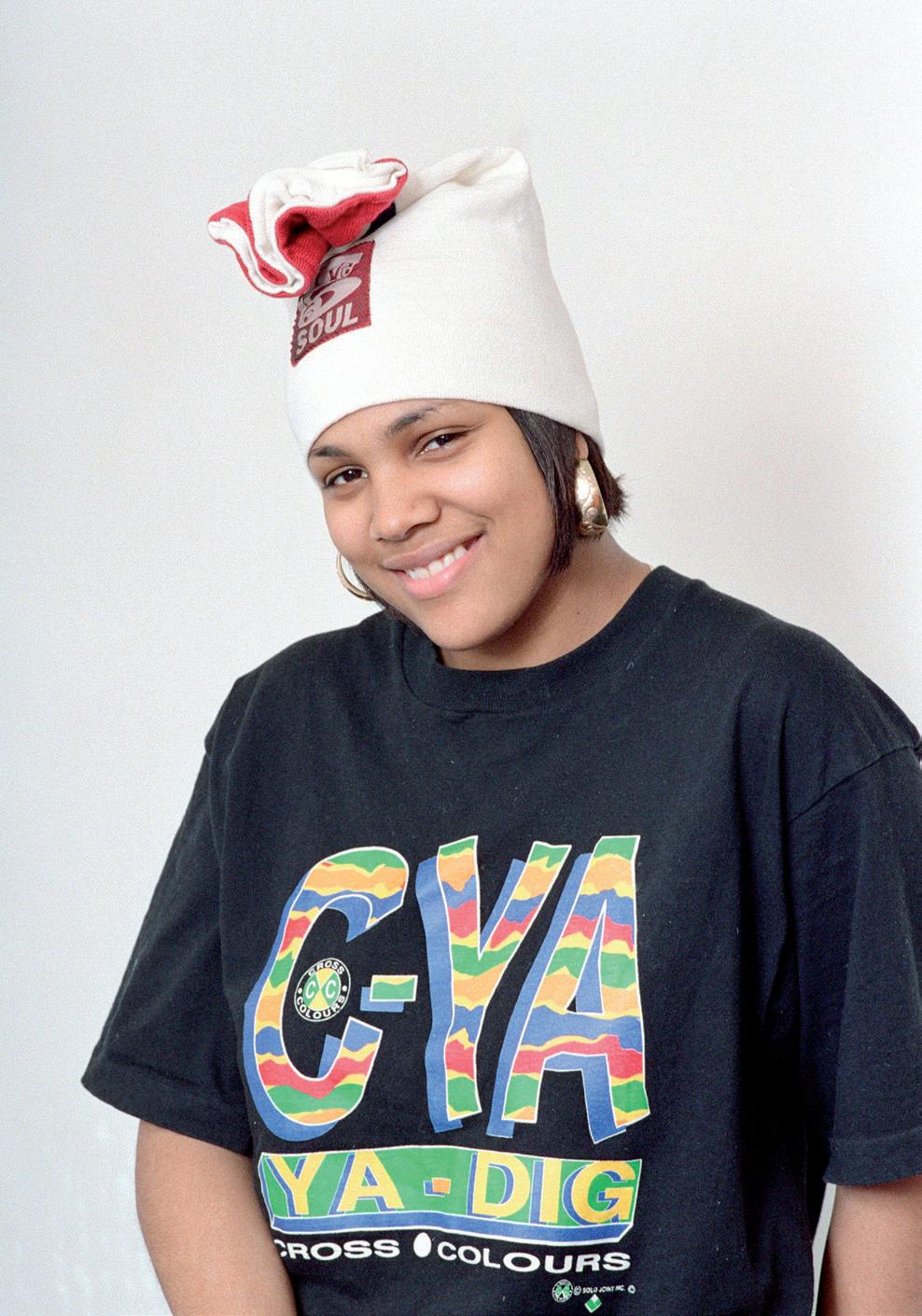

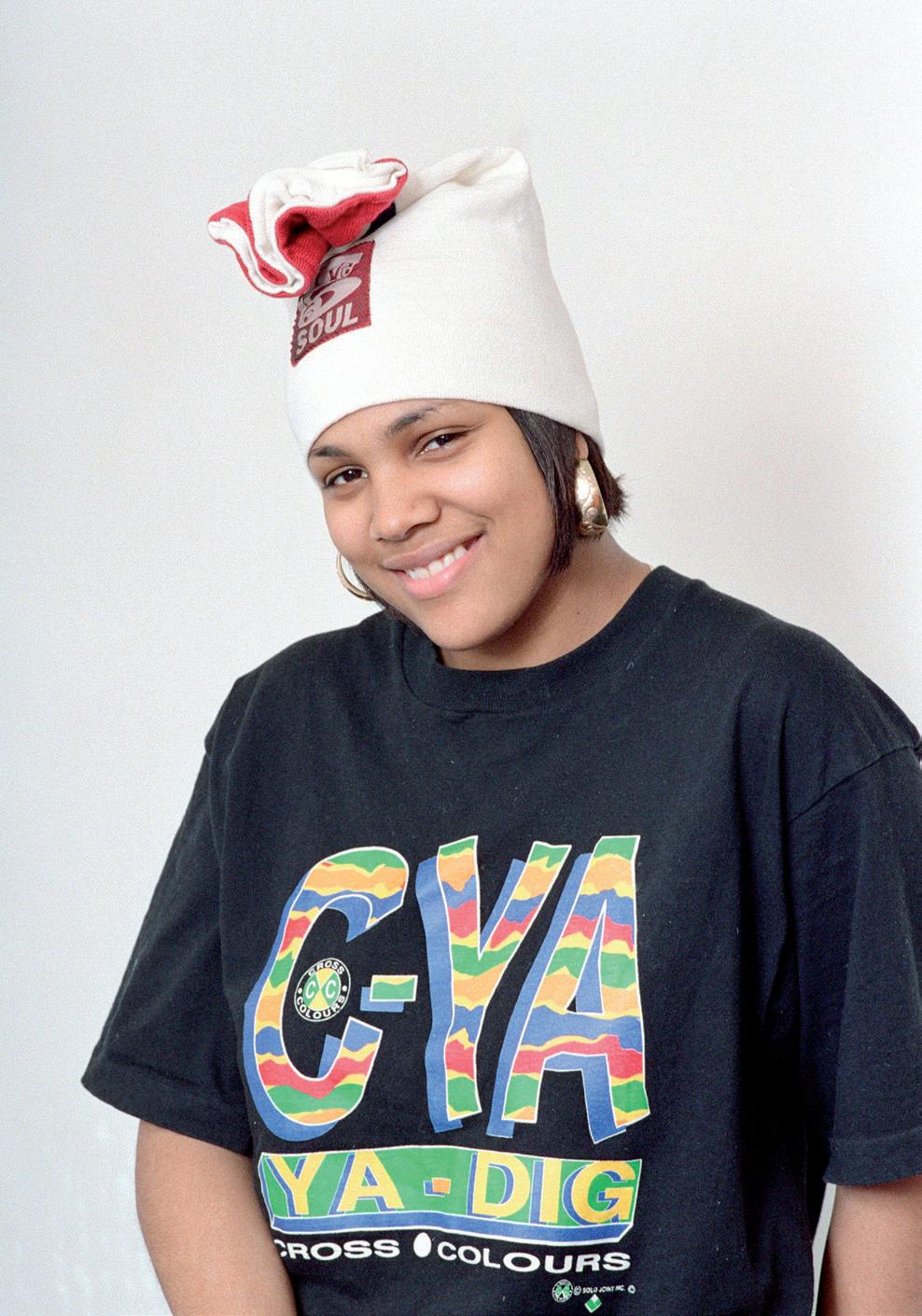

Monie Love

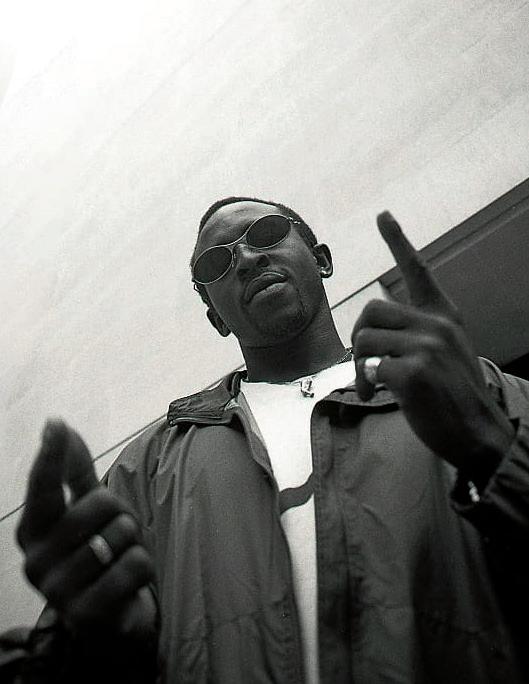

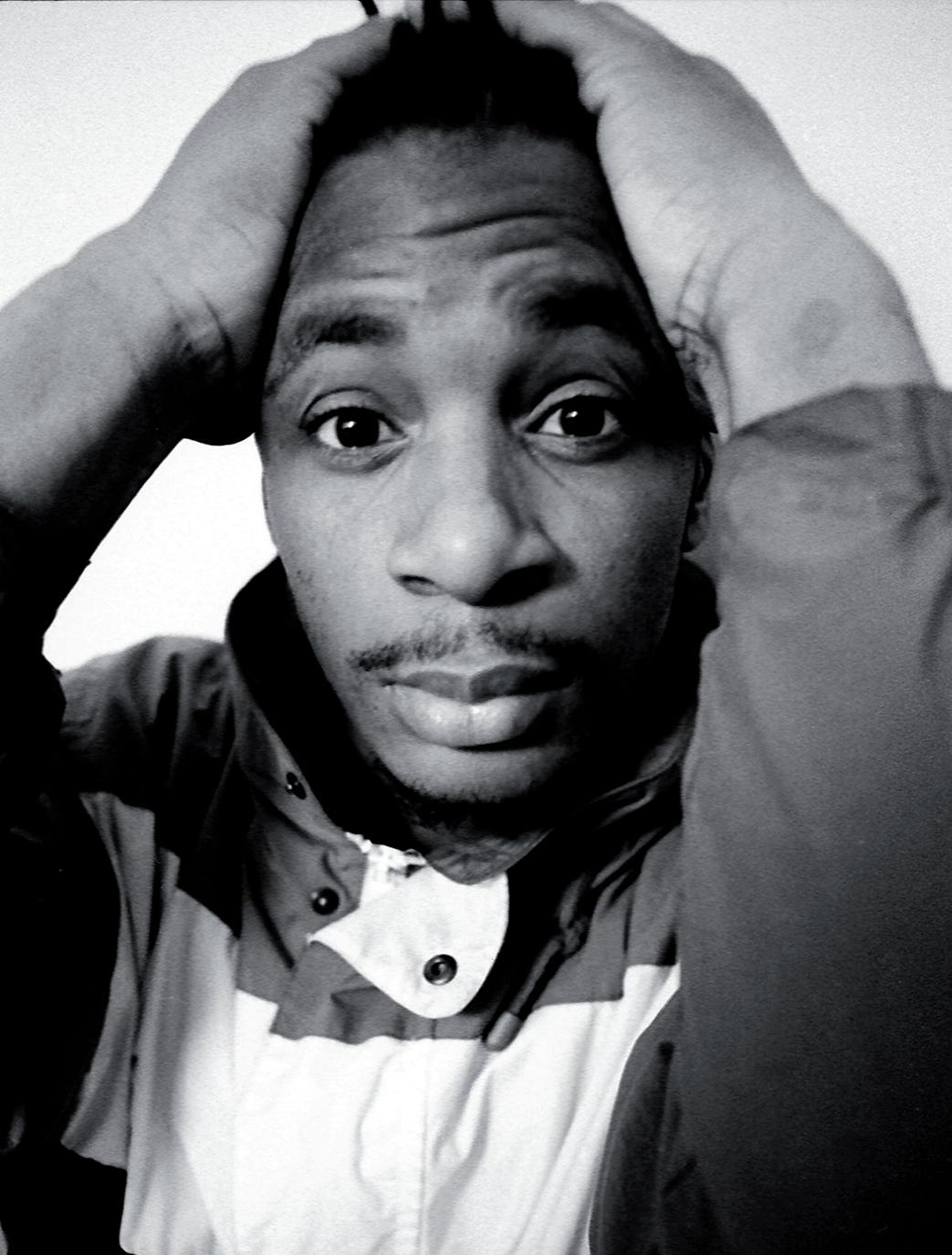

The south London rapper and MOBO-winner tells M about coming of age during hip hop’s foray into the UK music scene, and how he and his rap peers began to carve out this country’s distinctive hip hop identity.

By Joanna Chaundy

Even though his 1996 debut album Dettwork Southeast wasn't officially released until 2014, Blak Twang is undoubtedly UK hip hop royalty. The Londoner born Tony Olabode became one of the most successful UK rappers of his time, with five albums (including 2002’s Kik Off, which featured cover art designed by Banksy), a MOBO Award and collaborations with the likes of Rodney P, Roots Manuva and Estelle all under his belt.

There aren’t many other people in the UK more qualified than Blak Twang, then, to talk about the importance of hip hop’s 50th anniversary. 'No one expected it to last this long,’ Twang tells M about the enduring significance of the movement. ‘It changed and influenced everything: language, slanguage, fashion, the way we listen to and perform music. It’s music that best reflects life and making something from nothing: that’s hip hop.’

Having mainly listened to reggae while growing up, the first rapper who truly caught Twang’s imagination was KRS-ONE: as we speak, he starts singing the riff to Boogie Down Productions’ My Philosophy

'When hip hop started making some noise I got into Public Enemy and Big Daddy Kane, and then started properly immersing myself in it,’ he says. 'N.W.A. were a really big influence on me when I was 18, and I started taking hip hop more seriously and listening to what the artists were really saying: I was listening to the lyrics rather than just the music. It also gave me an insight into America, which I never previously paid attention to — particularly black America. All we saw was what was shown on TV, whether it was The Cosby Show or all those Blaxploitation

movies. But then listening to rappers really talk about their neighbourhoods, their struggles and their experiences on top of some wicked beats… that’s when I really said, “Yep, this is me.”’

As the ‘80s blurred into the ‘90s, hip hop began to seep into the London music scene — although, as Twang explains, you had to be ‘in the know’ to access it. ‘Hip hop was very popular in London, but also very underground,’ he says. ‘You had to be in with the right people and know what was going on to get to a gig: it wasn’t at your fingertips like it is now, you had to really work for it. It made you appreciate it more, because it wasn’t so easy.’

The first hip hop show Twang attended in London was Monie Love and MC Mell'O' at The Albany in Deptford (‘It was amazing’), but it was a while before he realised that he wanted to become a rapper himself. ‘Initially, I was just watching,’ he says. ‘Then around 1990, I was rolling with friends of mine who were already writing music.’ Those friends included Roots Manuva and the late TY, who died in 2020 shortly after completing a tour with Twang and Rodney P as Kingdem. 'We all used to go to this studio on the Angell Town Estate that a lady called Dora and her husband allowed us to use, and that’s when we started making demos.’

But what eventually convinced him to become one of the musicians he had so idolised? 'I started listening to Tim Westwood and Friday Nite Flavas, where DJ 279 would play a lot of UK rappers,’ Twang recalls. ‘That's where I used to start hearing rappers with a London accent, or whatever their local dialect was. I'd then go to [London venue] Borderline and would see people like Skinnyman and Fallacy there.'

'HIP HOP IS THE MUSIC THAT BEST REFLECTS LIFE’

He smiles as he then remembers a YouTube clip of him, Skinnyman and MCD doing a cypher together when they were younger. 'That was a day we all went to work on a track called UK Allstars, which was produced by Funky DL, a great producer. It was strange that we all showed up to the studio because that would never happen nowadays, but then it was an awesome time and era to be alive.’

Lyrically, Twang is renowned for using London slang and terminology in his music, and he credits various artists for influencing his writing. 'Nas was one of my biggest influences as far as writing goes, as well as Mobb Deep,’ he says. ‘I used to work with MCD in a studio down Holloway Road, which really made me see a different level of writing — London Posse as well. They were so creative with the words they chose, it just sounded so natural and conversational. I wanted to reach the levels they set for me, and then I put my own slant on it.'

He certainly achieved that: Twang’s lyrics were so personal to his native London that they may have even scuppered any chances of him being accepted by US music fans. Was that a conscious decision?

'I’m glad you asked that question,' he replies, leaning forward. ‘Yes, we consciously decided that we weren’t going to rap in American accents: we had to keep it authentic to ourselves. If you got up at an open mic night and rapped in an American accent, you were getting booed!

‘We championed that real London sound, using local language and colloquial slang,' he adds, with a smile. ‘It was a great time. The UK hip

hop movement grew and grew, and we were almost saying, “Stuff America". We didn’t mean it disrespectfully, but we didn’t want to be compared to our big brother: we wanted to be recognised for what we did. That started to happen when BBC Radio 1Xtra came about and people could hear us everywhere, which really propelled the UK hip hop scene. It’s gone from strength to strength ever since.’

Twang cites the likes of Dave, Wretch 32 and Kano as some of his current favourites, but, as a veteran of the game, he also makes sure to give plenty of credit to his predecessors. 'There’s nothing I can tell ‘em: they’ve already done it,’ he says about the current generation of musicians. ‘They’ve taken what we had and learned from our mistakes, and now they’re capitalising on it in the way we couldn’t.’

M Magazine | 5 Photo: Tee Max

'We consciously decided that we weren’t going to rap in American accents: we had to keep it authentic to ourselves.’

GROUNDBREAKING GROUPSof uk hip hop

the

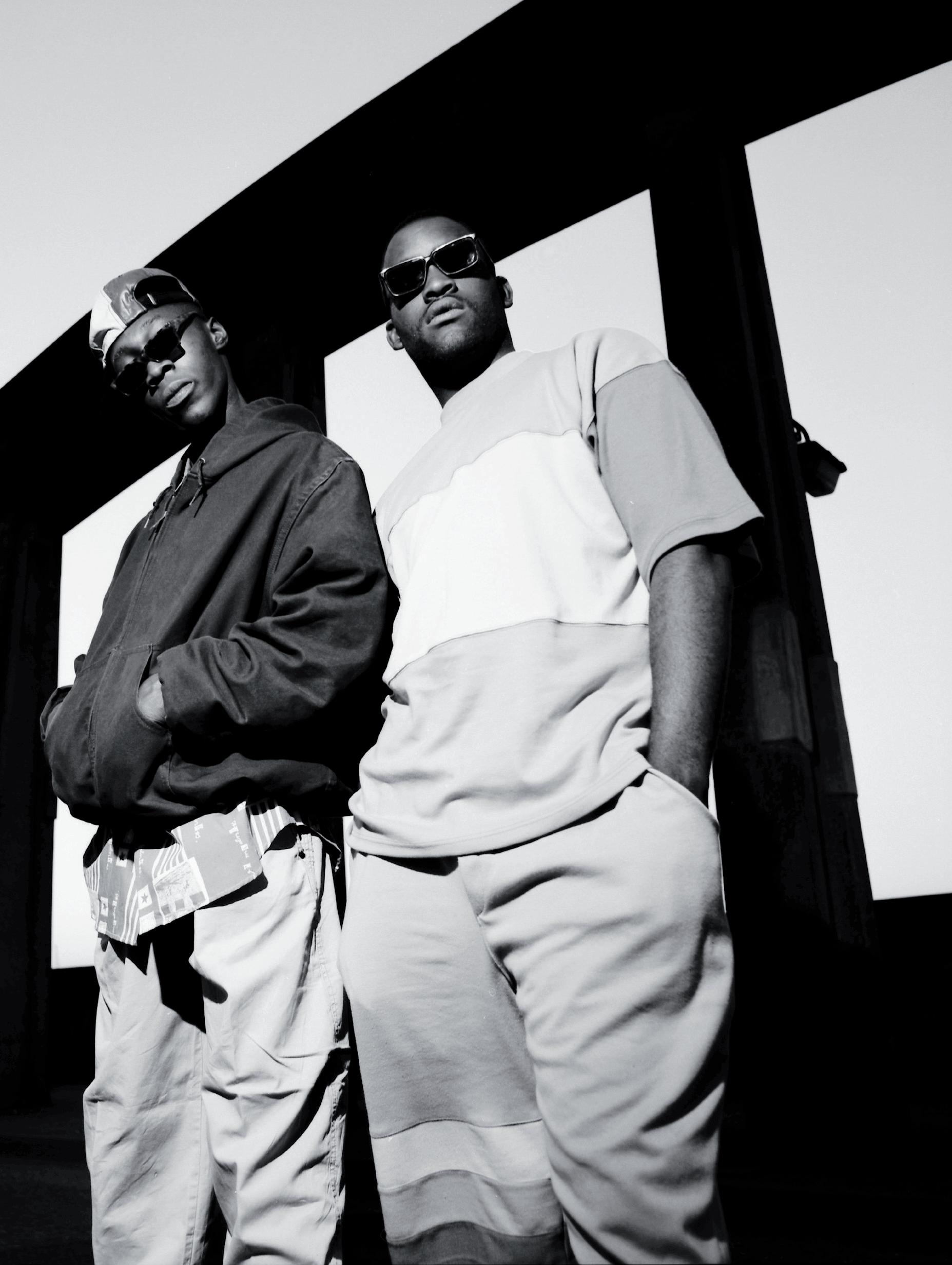

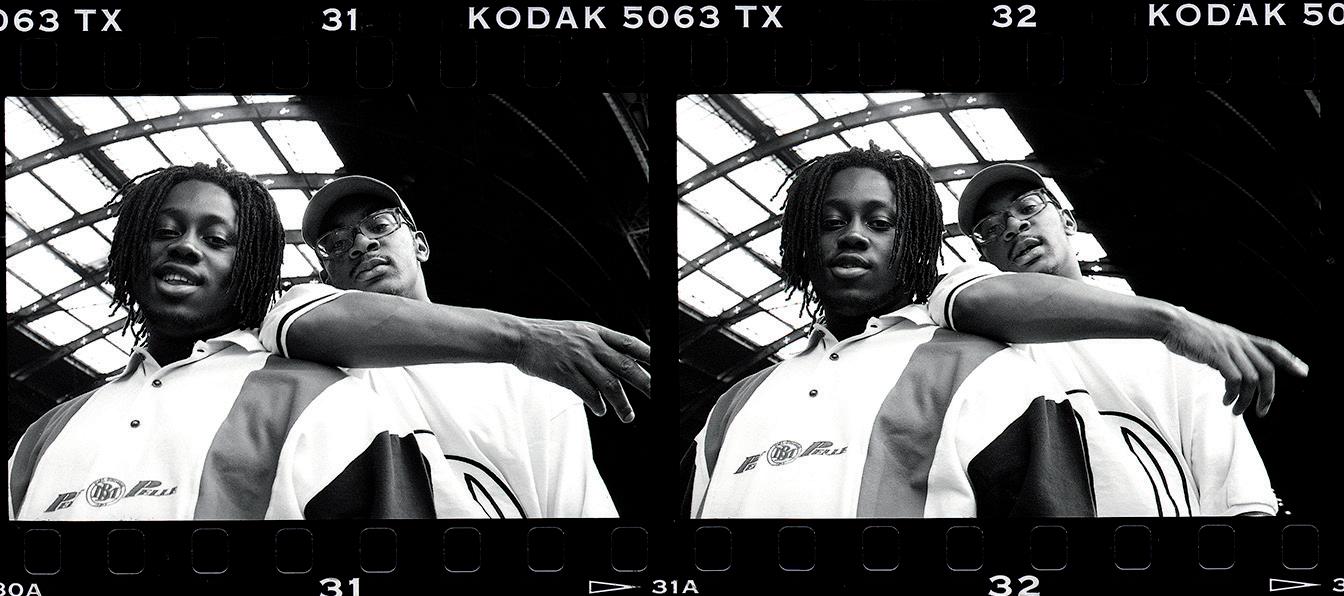

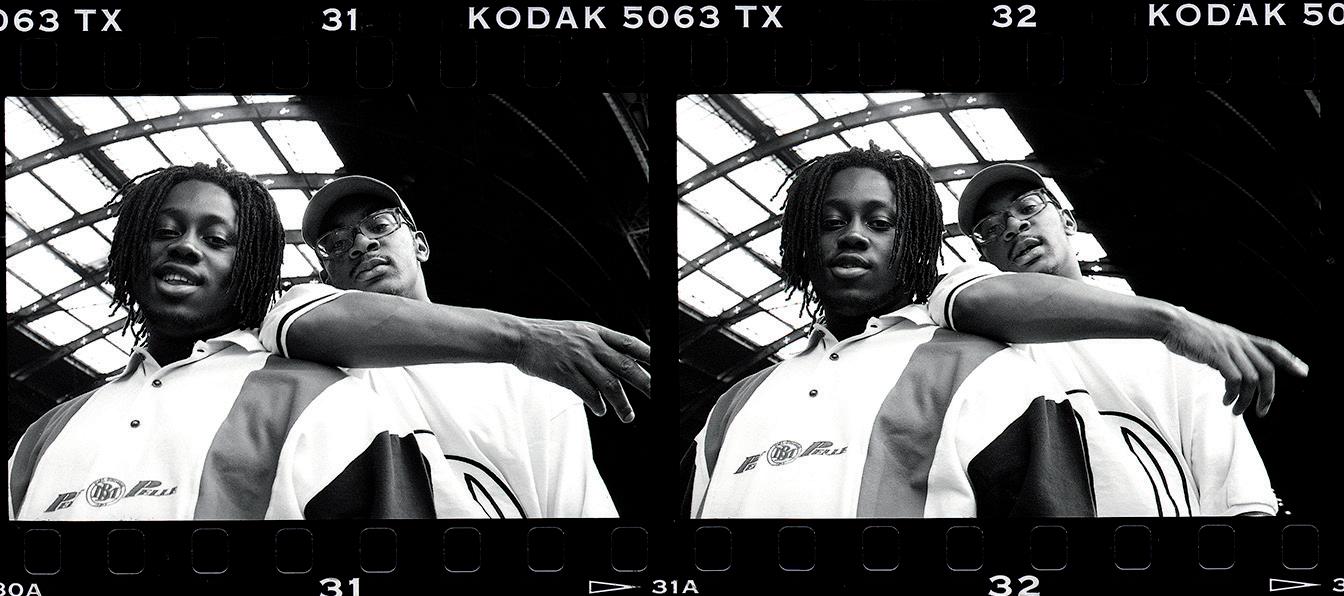

Above: London Posse

Above: London Posse

From London Posse to Cookie Crew, a host of pioneering hip hop groups helped lay the foundations of the UK scene. M traces these acts' groundbreaking contributions, musical innovation and enduring impact on the hip hop landscape.

By Angus Batey

Whether it's Little Simz winning the Mercury Prize, Dave topping the UK album chart or Stormzy headlining Glastonbury, British hip hop looks indomitable. According to the BPI, only pop and rock accounted for more album consumption than hip hop in the UK in 2022, with British artists responsible for the lion's share of those sales and streams. The genre also commanded almost a fifth of the singles market, with eight of the 10 most-streamed and highest-selling tracks by UK artists.

Yet for many years, British rappers were ignored by the media, music industry insiders and even UK rap fans. Regarded all too often as middling talents at best, they were cast as imitators in thrall to the American innovators; wannabes incapable of competing with the avalanche of adventurous, exciting music making its way across the Atlantic. Not only was this deeply ingrained misconception ignorant and unfair, it relied on a series of selective elisions and misinterpretations to retain its shape. Yet despite having little credible basis in fact, this dismissive view held back a scene that is only now beginning to realise its vast potential.

Hip hop made its way across the Atlantic in a kind of audio-visual samizdat form. Brits with friends or family in New York began to receive cassettes made at Bronx park jams or Brooklyn block parties in the late 1970s, alerting them to the new sound being created out of old records by pioneering DJs and adventurous MCs. The art form's visible manifestations — graffiti art and breakdancing — made landfall in Britain first, but the early rap records weren't far behind: the Sugarhill Gang's Rapper's Delight, the first hip hop hit, reached number three in the UK charts as the 1980s dawned.

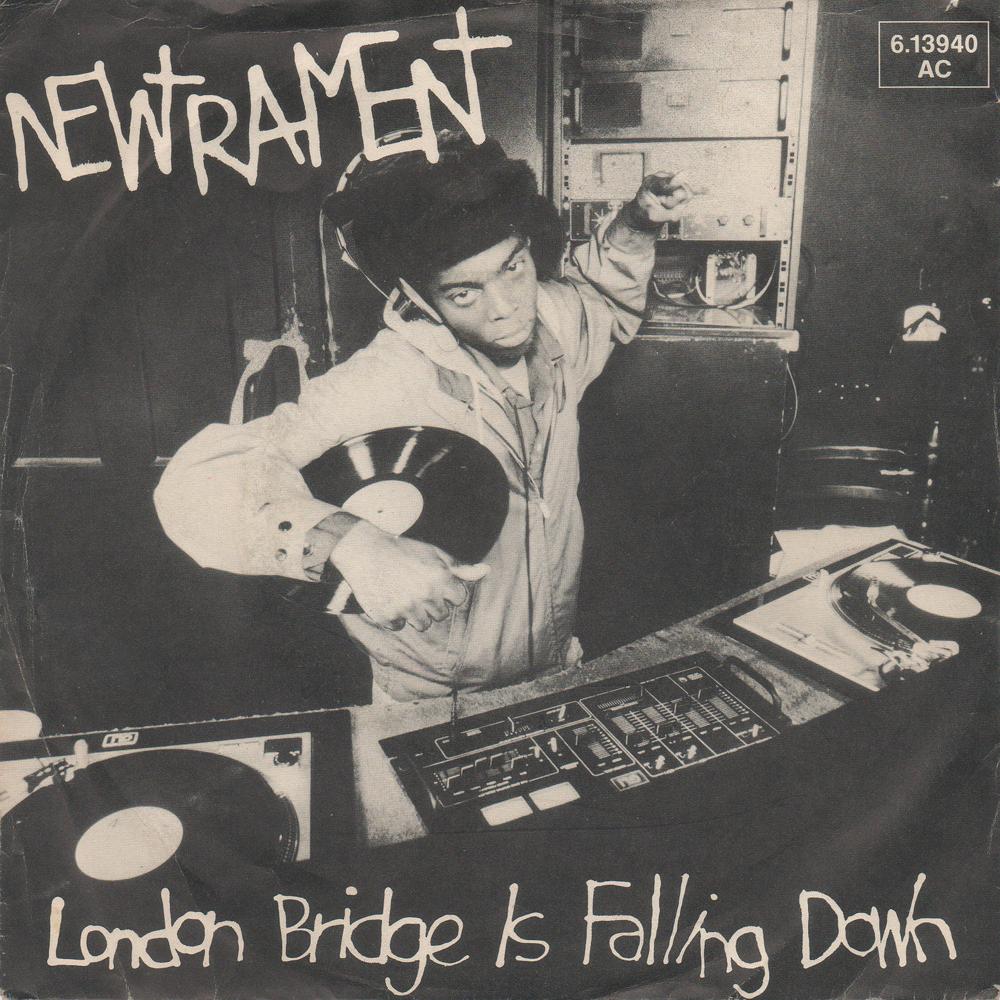

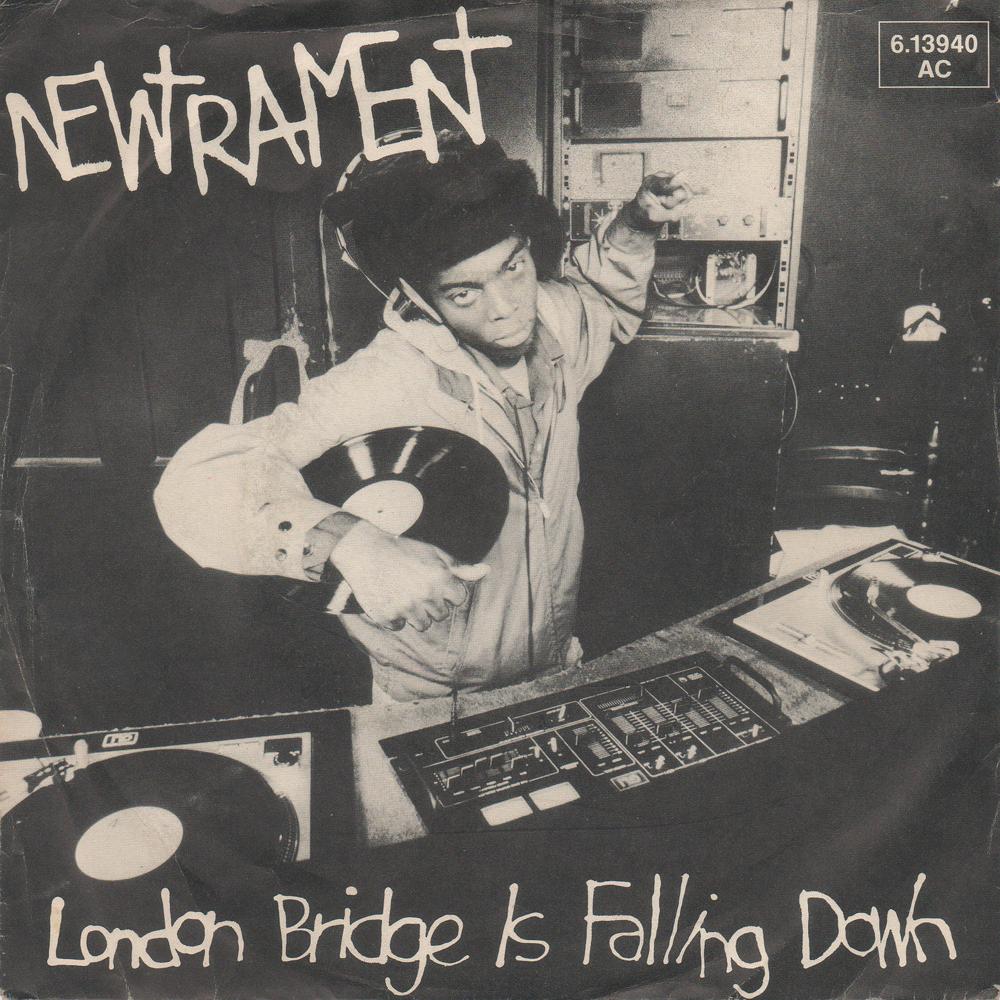

In many respects, then, we shouldn't have been surprised that British musicians began making rap records — only that it took them so long to do so. Just as in the US — where the Fatback Band's B-side King Tim III (Personality Jock) beat the Sugarhill Gang to the record racks — there is debate about what was the first true British rap record. Newtrament's London Bridge Is Falling Down appears to have been recorded earlier, but it was Dizzy Heights' Christmas Rapping that came out first in December 1982. In the late '80s, industry naysayers would claim the UK had insufficient fans to turn British rap records into hits, suggesting that major labels would never invest in a supposedly inferior, non-US version of the product. Yet Newtrament's single was released by the Arista-distributed Jive, a label that would become synonymous with creative, credible US hip hop, while Christmas Rapping spent four weeks in the Top 75.

Just as notably, these releases came after established British artists from other genres had begun to warm to hip hop's creative potential. The Clash experimented with elements of rap on their 1980 album Sandinista! , while guitarist Mick Jones would absorb hip hop into his creative process when he and The Clash's videographer, Don Letts, formed the band Big Audio Dynamite in the

M Magazine | 7

‘After bumping into him in the queue at a London McDonald's, She Rockers got Public Enemy's Professor Griff to produce their debut single.’

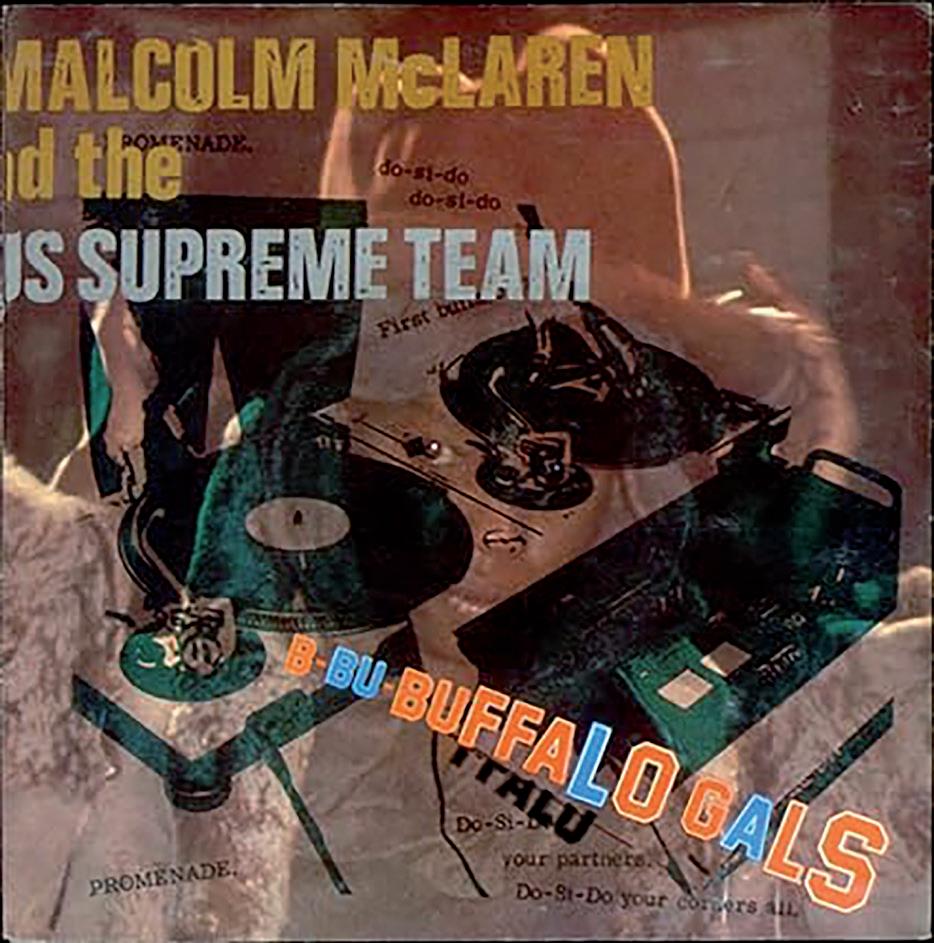

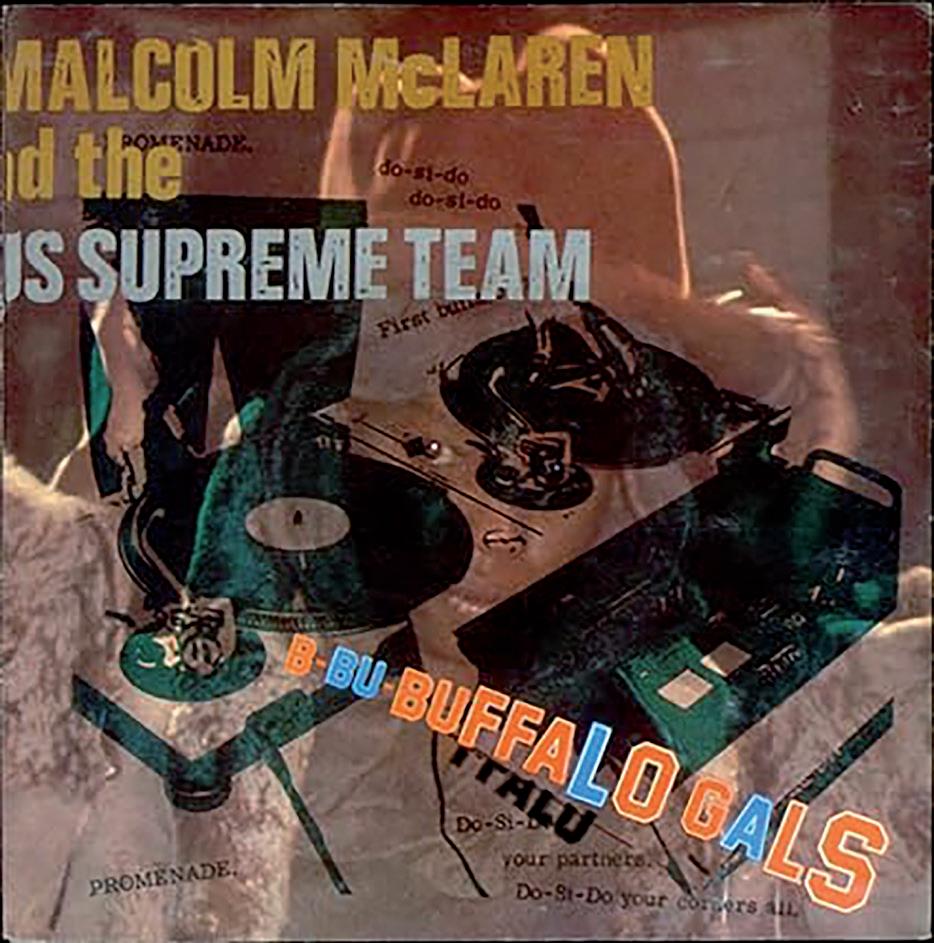

mid-'80s, bringing London Posse member Sipho into the charts in 1986 as a featured artist on the single C'mon Every Beatbox. Pop band Wham! and post-punk outfit Adam and the Ants, meanwhile, both released rap singles in the early '80s. If these efforts made little impact within the UK’s nascent hip hop scene, the 1982 release of Malcolm McLaren's Buffalo Gals was seismic — even if, by relying on New York musicians and shooting the epochal video in the US, it can't really qualify as the first real British rap record.

Early British rappers were savvy enough to make a virtue of their differences, but the influence and inspiration of American hip hop was pivotal. Key dates in the UK rap timeline, therefore, include the UK Fresh '86 festival: organised by Capital Radio and the Streetsounds label (which had found a niche by licensing US rap 12"s and repackaging them as affordable compilation LPs), the all-day event at Wembley Arena brought New York's A-list to London. The DJ service Disco Mix Club hosted its first DMC World DJ Championship in London the same year, with Fresh '86 opening act DJ Cheese its inaugural winner. By November 1987, the city was so well established on the hip hop map that Public Enemy would choose their support slot to LL Cool J and Eric B & Rakim at the thenHammersmith Odeon as the place to record the fevered crowd response segments that were dropped in between songs on their 1988 masterpiece, It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back

The music's power dynamic might not have been starting to shift exactly, but if the big names in the US had previously thought of the UK as just another territory to shift units in, many of them were now aware there was a new scene coming together in Britain and were ready to take British artists seriously. After bumping into him in the queue at a London branch of McDonald's, west London trio She Rockers got Public Enemy's Professor Griff to produce their debut single. Brixton six-piece Hijack were spotted by Ice-T and soon signed to his Rhyme Syndicate label, while Londoner Cutmaster Swift emerged victorious in the 1987 DMC final.

By 1988, when London Posse's single Money Mad laid those 'copying the Americans' critiques to rest with cockney slang and London-accented rhymes, British rap was on a roll. The Music of Life label was providing a home for this sudden explosion of new British rap acts: its A&R man Derek B became the first UK hip hop artist to appear on Top Of The Pops, rapping about being pulled over by the old bill on the M4 in Goodgroove. The female duo Cookie Crew (above right) had already scored a US dance chart hit with the anthemic Females and soon found themselves in the storied Calliope Studios in New York, where De La Soul and the Jungle Brothers had made classic LPs, working on a debut album with members of Stetsasonic.

Hijack, meanwhile, had almost single-handedly created a new sound with their blisteringly fast second single Hold No Hostage, released by Music of Life in 1988. Battle Creek Brawl, the debut release from trio Gunshot, took a leaf out of the Hold No Hostage playbook, before Hardnoise's Untitled and tracks like Blade's much-loved 1990 B-side Forward turned an idea into a sub-genre.

British artists ran the gamut, from the likes of Definition of Sound and Outlaw Posse who embraced melodic sampling, to the militant politics of Black Radical Mk II and Katch 22. Stereo MC's — early British rap's biggest band, even if they weren't routinely considered part of the scene — began as a trio with two rappers and a DJ, before recruiting a drummer and backing singers and winning two BRIT Awards for their chart-topping 1992 album Connected. Over time, British artists who grew up on hip hop would come to dominate charts and venues worldwide. Be it The Prodigy, whose musical driving force Liam Howlett had been in a rap group and won a Capital Radio scratch-mix competition; Massive Attack, whose members included storied Bristol graffiti artists

'Over time, British artists who grew up on hip hop would come to dominate charts and venues worldwide.’

and whose sound and style was based around looped samples and scratching; or Norman 'Fatboy Slim' Cook, whose debut album was a breakbeats collection released on Music of Life and whose first big hit was a remix of Eric B & Rakim.

Yet it was the so-called Britcore sound — those uptempo, skittering beats allied to rapid-fire rhymes that were instigated by Hijack, Gunshot, Hardnoise and Blade — that would become arguably the most important and influential development in British rap's foundational years. During the late '90s, when US hip hop became the globe's dominant genre, European fans who prized authenticity and integrity over the partying and excess that characterised the American hits elevated Britcore, treating it as the last bastion of the old-school values of independence, integrity and a refusal to sell-out. By the turn of the century, as drum’n’bass, speed garage and grime respectively developed the idea of spitting fast rhymes over hard, sped-up beats, what had at first been decried a stylistic dead end came to be seen as the first manifestation of a new, and uniquely British, approach to hip hop.

M Magazine | 9

'For many years, British rappers were ignored by the media, music industry insiders and even UK rap fans.’

M explores the poetic evolution of UK hip hop lyricism, from its roots in the Windrush Generation to modern-day greats like Dizzee Rascal and Giggs.

By Jesse Bernard

By Jesse Bernard

Over the past 50 years, hip hop songwriting has been primarily built around storytelling and world-building, elements which can be traced back to the genre’s roots in gospel, blues and jazz music. At its core, the retelling of the Black American experience, both individual and collective, is the very clear thread that weaves these styles together, greatly influencing the music that is created.

To understand the fabric of hip hop in any country it has a strong cultural presence in, an acknowledgment of migration patterns is imperative. While the Great Migration — when approximately six million Black people moved from the American South to Northern, Midwestern and Western states between the 1910s and 1970s — birthed a wave of industrialism and urbanisation in major cities across the US, Black migration to the UK didn’t occur en masse until the Windrush generation of the mid-20th century. Many of these Black immigrants came from Caribbean countries where both gospel music and sound system culture were prominent, and these two traditions were brought with them upon their arrival to the UK, forming the roots of Black British music.

Fast-forward to 1980s Britain, which, to many, evoke ugly, This Is Englandstyle images of Thatcherism, widespread social unrest and the National Front. But for young Black people in Britain, this decade marked the shaping of a Britain that was markedly different from what their parents and grandparents first encountered. They were arguably the first generation of Black people in the UK to self-identify as being British, though, it should be noted, they still primarily considered themselves to be Black first. This generation had to contend with rising youth unemployment levels along with the antagonism, prejudice and racism they regularly faced from those they shared classrooms, workplaces and public spaces with. Long-standing tensions between the Black community and the police, stemming largely from the latter’s disproportionate use of the ‘sus law’ against young Black men, sparked riots in Brixton, Tottenham and Toxteth in Liverpool.

M Magazine | 11

dizzee rascal

Young Black people were already able to creatively express their frustrations at this time through reggae and dancehall music, but thanks to increased media exposure from the US, they were also learning how their stories could be told in other forms. Early UK hip hop acts such as Demon Boyz, London Posse and Monie Love, who all emerged on the scene in the late '80s, began crafting the language rappers on these shores are still using today, basking in the freedom afforded by a relative lack of songwriting rules.

Despite this, UK hip hop did suffer from something of an identity crisis during those early years. With the genre still finding its feet in this country and US acts only just beginning to tour internationally, several UK artists began to rap in American accents in the belief it would give them the necessary crossover appeal on both sides of the pond. London Posse member Bionic was instrumental in changing this approach, as the group blended their style of rap with ragga music, while the later emergence of jungle, UK garage and grime gave license to British artists to feel empowered by their accents and speak authentically in a language their audience could identify with.

Dizzee Rascal’s song Sittin’ Here, which opened his seminal 2003 debut album Boy In Da Corner, was a watershed moment for what would eventually become grime music. Consciousness of thought wasn’t necessarily new to the jungle scene Dizzee came from, but Boy In Da Corner was a completely new entity; an undiscovered and unchartered area of music. Music critics and fans alike would come to cite Sittin’ Here as a powerful stream of consciousness that explored themes of depression and youthful angst:

im just sitting here i aint saying much i just think

and my eyes dont move left or right they just blink

i think too deep and i think too long plus i think im getting weak cause my thoughts are too strong

im just sitting here i aint saying much i just gaze

im looking into space while my cd plays

i gaze quite a lot in fact i gaze always and if i blaze then i just gaze away my days

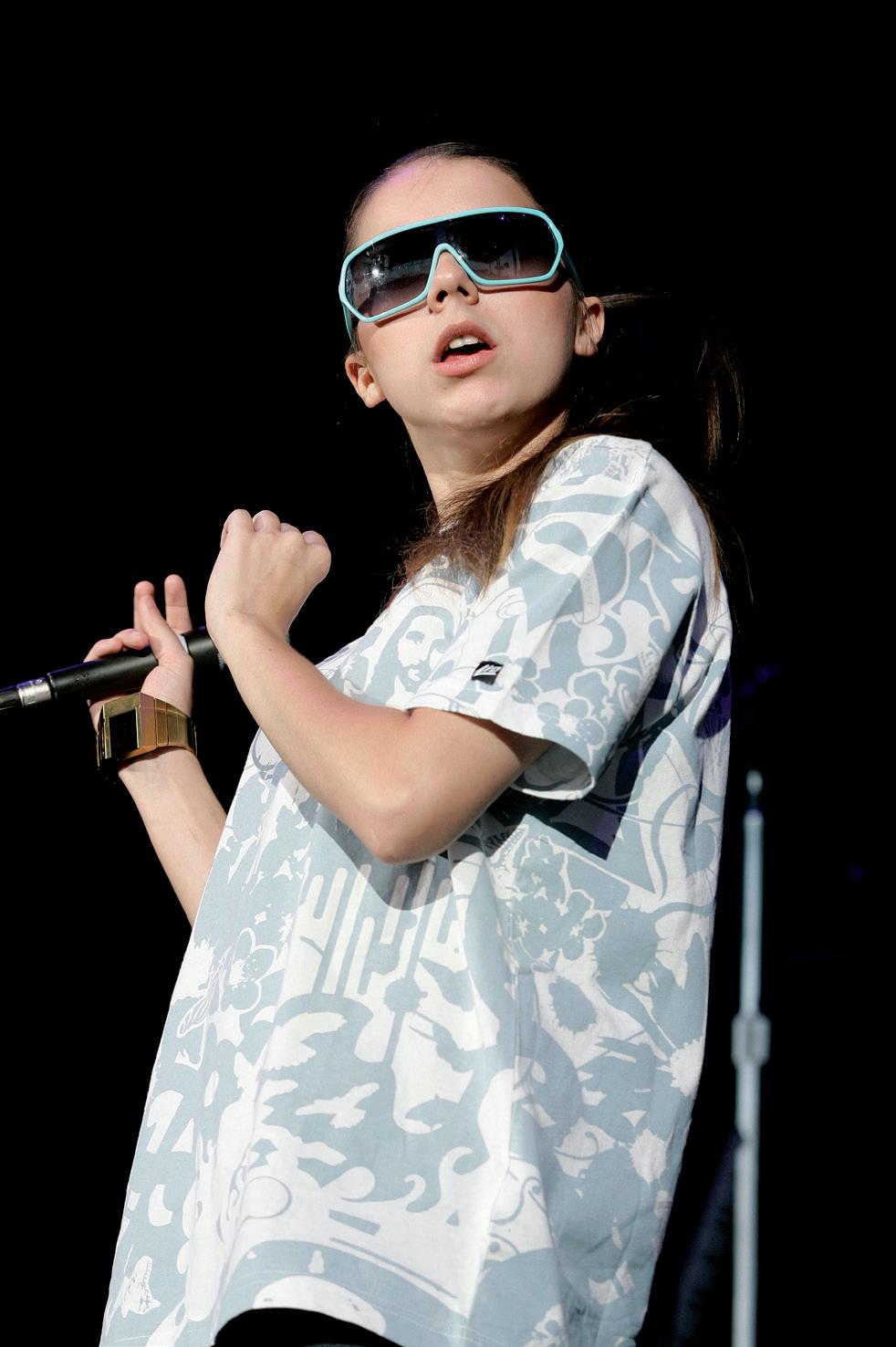

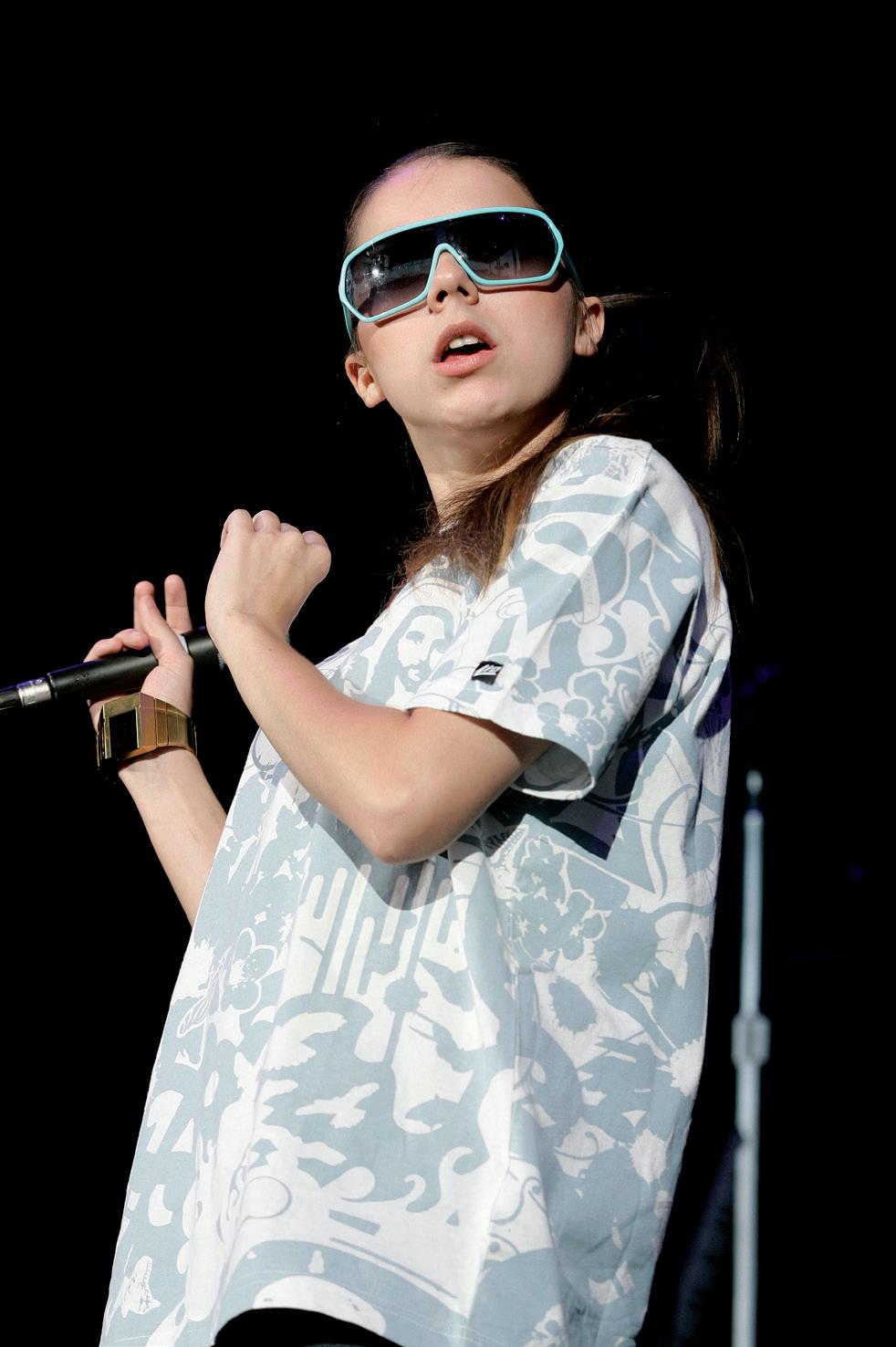

lady sovereign

It wasn’t until the early 21st century that UK hip hop, spearheaded by the likes of TY, Skinnyman, Akala, Jehst, Klashnekoff, Shystie, Lady Sovereign and Roots Manuva, began to establish itself as a substantial force in British music. Each of these artists possessed undeniably British cadences and language yet still operated in their own unique spaces, illustrating the breadth of styles within the genre. Take Skinnyman’s 2004 debut album Council Estate of Mind, which represented the working-class through his tales of growing up in housing estates in Islington, one of the UK's most socially deprived areas. The metaphor-laced rhymes of Hackney’s Klashnekoff, on the other hand, possessed punchlines that vibrated through the speakers and hit your chest. To this day, he’s still recognised for creating one of the most memorable UK hip hop anthems in Murda, in which he infamously referenced the 1999 murder of Panorama presenter Jill Dando.

A few years on came the rise of road rap, which was more akin to the gangsta rap found on the east and west coasts of the US. Giggs’ 2007 track Talkin’ da Hardest was the torchbearer, with the Peckham rapper taking the beat from Dr. Dre and Eminem protégé Stat Quo’s Here We Go and making it undeniably British. If you were to ask anyone today who that beat belongs to, most would say Giggs because of the way he gave rise to a completely new style of songwriting in UK rap. His lyrics were simple but effective, employing rhyming couplets so it felt as though each verse contained multiple haikus as opposed to the more traditional storytelling heard in rap: giggs

M Magazine | 13

flipping like a quarter a brick bag 28 with a thought of a jib anybody thinks they can talk to my clique will end up covered in red like a portion of chips pour me a drink big fur jacket thats the thoughts of a pimp

'Early UK hip hop acts such as Demon Boyz, London Posse and Monie Love began crafting the language rappers on these shores are still using today.’

Giggs has never been one to shy away from articulating his experiences of life on the road: rappers of his ilk see the brutal reality of street life, which, in some ways, is its own level of consciousness. Talkin’ da Hardest offered a more rounded, if bold and illicit, view of what inner city life was truly like for many young Black people. If the late ‘90s had witnessed a lyrical shift towards more ostentation, Giggs sought to drag the form back towards a rougher and more ominous path as though he was saying, ‘This is what this life is really about’.

In a country that routinely neglects the working-class and other marginalised groups, and where social mobility is exclusive, telling your story through music is one of the ways in which UK rappers and MCs can take hold of their narrative. This was never more vividly and profoundly felt than on So Solid Crew member Swiss’ 2005 track Cry. I remember first hearing the song when I was in Year 10, and for those that looked like me, Swiss gave us a language that spoke to our existence. We couldn’t quite explain why we had to work twice as hard, but we knew that we had to. The murders of Stephen Lawrence in 1993, Damilola Taylor in 2000 and Anthony Walker in 2005 reminded us that we were the other in the most violent of ways.

Cry was the balm to both Sittin’ Here and Talkin’ da Hardest

The song saw Swiss attempt to answer why Dizzee felt the way he did on the former, while also attempting to offer some perspective as to why people like Giggs ended up being pulled towards the street:

does the lord half care?

theyre just eating bread while everybody starves there

look what happened to the motherland

they dont wanna see blacks the same as another man

and just cos our skins a different colour

i dont change colour but they call me a coloured man

theres only so much you can take in when your heads nappy and with the shade of a slaves skin

the ghetto spent most of my days in

i aint in prison but i feel like im caged in

roots manuva

‘The emergence of jungle, UK garage and grime gave licence to British artists to feel empowered by their accents.’

It was as though Swiss was expounding on the many notes he took over his years growing up in south London, leading him to ask questions of why the likes of Dizzee and Giggs had to be in the positions they were in in the first place. Cry gave young people the words they couldn’t find, imagining a world where Sittin’ Here and Talkin’ da Hardest didn’t exist and instead offering hope and a sense of perspective. There was a Black consciousness beginning to form in UK rap, and while the artists might not have always been able to articulate just how and why life was that way outside of the music, if you gave them a pen and a pad, they could rival some of history’s most prolific thinkers when it came to race and social class.

Then there were those who found themselves straddling the very thin boundary between grime and rap, which still exists today. Justin Uzomba, formerly known by his stage name Mikill Pane, recalls attending rap events as a teenager where grime MCs would attend, and vice versa. There was a mutual respect between the two genres: after growing up and living in the same neighbourhoods and going to the same schools, many of these artists would then cross paths at these events, particularly as spaces were few and far between for rap and grime at the time.

By the mid-2000s, there were three clear strands under the umbrella of hip hop in the UK: UK hip hop, UK rap and grime. The nuances between the three could generally be separated by tempo and the medium in which they were delivered. At the time, grime existed primarily in live radio sets or clashes, while UK hip hop took on a more traditional format through its mix of studio albums and live shows (a more accessible form for audiences who weren’t in regions where pirate radio was prominent). UK rap, meanwhile, largely consisted of freestyles over US rap beats.

While US hip hop has historically been seen as setting the gold standard when it comes to songwriting and storytelling, UK hip hop’s influence can’t be underestimated. With a clear and traceable lineage that separates it from the US, the UK proudly exists in its own lane — a fact that could only come about through an acceptance and embrace of our roots and history as Black and marginalised people in Britain. Indeed, in 2023, artists such as Central Cee, Dave and Little Simz can be regarded as prominent and genre-leading globally, not just the UK.

UK hip hop’s unique history stands it apart from the country where the genre originated. It can feel like an uphill battle to prove this due to the overarching lore and canon of US hip hop history, which has been retold endlessly. But what has come from the UK since hip hop’s introduction to these shores is more than capable of standing tall, still proudly embracing its authentic roots.

'If you gave UK hip hop artists a pen and a pad, they could rival some of history’s most prolific thinkers when it came to race and social class.’

monie

M Magazine | 15

love

Breaking down barriers as a female hip hop artist

Whether in the US or the UK, women have always been invested in hip hop. While many female artists, particularly those from underrepresented backgrounds, have been marginalised over the years, we're now seeing more women than ever making it to the forefront of hip hop. What is also important to unpack is that the conscious rappers — those who choose to tackle difficult issues in society, politics or real-life suffering - are still being driven further and further underground.

Often referred to as Scotland’s first female rapper, I have had the honour of working, touring and recording with some of the greatest artists of all time during my career. This is my story.

I was born and raised in Edinburgh, and, at the age of 14, I was lucky enough to join the band NorthernXposure alongside Revelations (the founding father of Scottish hip hop) and arguably Scotland’s best hip hop DJ, three-time DMC Champion Ritchie Ruftone. At that time, hip hop was not embraced by the wider Scottish music industry, and many found the accent difficult to swallow. Undeterred, I took it to London and performed live in Covent Garden and Deal Real, Soho’s now-closed hip hop specialist record shop.

Back in those days, if you weren’t on tour, you weren’t a real rapper. Making music for your friends didn't count and there was no social media, so if you wanted people to hear your music, you had to physically be there in the room with them. I toured and worked with a whole host of UK legends — including Estelle, Amy Winehouse, Lethal Bizzle, Sway, Giggs, Fallacy and Fusion, Kano, Jehst,

Blak Twang, MCD and Akala — before going on to join Skinnyman’s Mud Family and Roots Manuva’s Banana Klan collectives. The work rate back then was intense: there were no shortcuts, and it wasn’t for the faint-hearted.

After the success of our 2009 album The Last Piece of The Puzzle, we were invited on tour with Damian Marley and Nas, received recognition from the MOBOs and became the first unsigned Scottish rap act to play at Glastonbury. Add to that appearances on Jools Holland, Tim Westwood and BBC's The Culture Show, and it still feels strange to look back and realise we were not only making Scottish hip hop history, but also UK music history.

Music, for me, was all about creating a competing ideology. I had no problem sacrificing fame or money as it was always about the music, interacting with the audience and the feeling you get when you know you've rocked a venue. My life and work were always about connecting the past with the future, whether promoters understood it or not.

At home there was not only racism, but real and physical persecution as well. I would promote shows by myself, bringing major artists such as Busta Rhymes and The Game to Scotland. Local lads, though, would rip down my

The Edinburgh artist now part of hip hop collective LOTOS takes us through her against-the-odds journey as Scotland’s first prominent female rapper.

‘I had no problem sacrificing fame or money, as it was always about the music.’

posters and pay their money just to give me abuse. It was madness, albeit a totally different time. But, as Skinnyman said, if they're not hating, you're not doing something right.

It wasn’t all doom and gloom, though, as there were also good people at home and abroad. Joining forces with Glasgow sound system Mungo’s Hi Fi gave me a new lease of life, renewing my love, joy and faith in music and leading me to roots reggae. I toured Europe with the Spanish rap group Violadores Del Verso, played internationally with artists such as The Skatalites, The Mighty Diamonds, Yellowman and John Holt, and recorded with Sugar Minott, DJ Vadim and Fat Freddy's Drop. In the US, I toured with the likes of Naughty By Nature, The Roots, Mos Def and Talib Kweli, while a career highlight came when I performed at Barclays Center in Brooklyn as part of the Ruff Ryders Reunion show. Playing on the same bill as the late legend DMX did enough to quench my thirst for music after decades in the game.

Relying on my talent helped me gain the respect of my peers. While massive labels offered deals which were never right for me, I was always hyper-aware of the history of Black music, the struggles of African Americans and the many artists who sacrificed their lives for the game at home and abroad. For me, though, it was always about creating real music, not striving for awards or being a slave to the industry — something that many people didn't respect, aside from the true hip hop heads and the originators of the culture who paved the way.

Working with Police Academy star and beatboxer Michael Winslow in the US taught me that hip hop didn't have to be about how hard, tough or sexy you could be. Instead, it’s a chance to make real music and real art. I accepted there and then that, like most women in hip hop, my contribution may be written out of music history, but it would forever be preserved in the hearts and minds of those who came to see me perform live, bought my merchandise and loved me because I refused to conform. I never exploited myself or made anything less than pure, unadulterated art, and what I have now is dignity, clarity and success.

Where we are today is a beautiful thing. Artists can take control of their own destiny by using technology and social media to forge a path of their own, while many institutions in the industry are finally trying to give a voice to the voiceless. But, of course, we still have more to do.

M Magazine | 17

‘Playing on the same bill as DMX did enough to quench my thirst for music after decades in the game.’

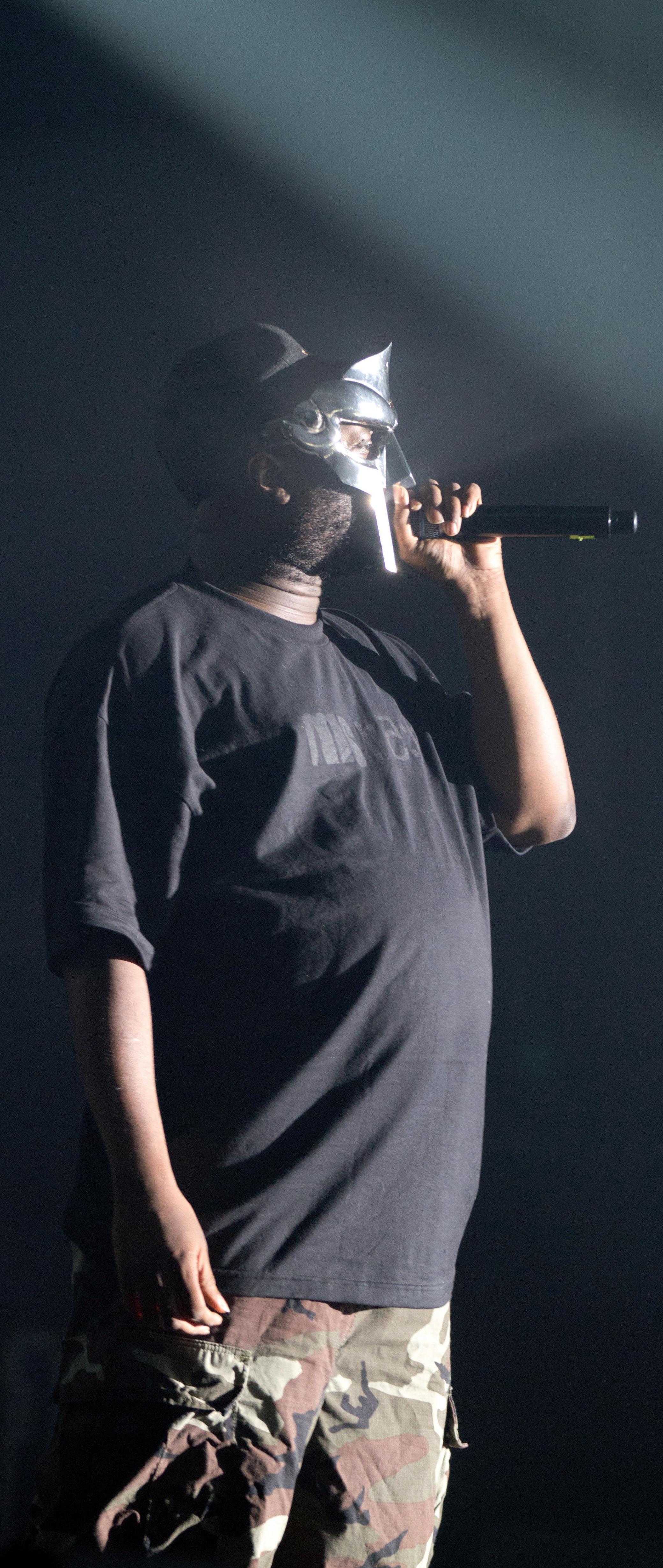

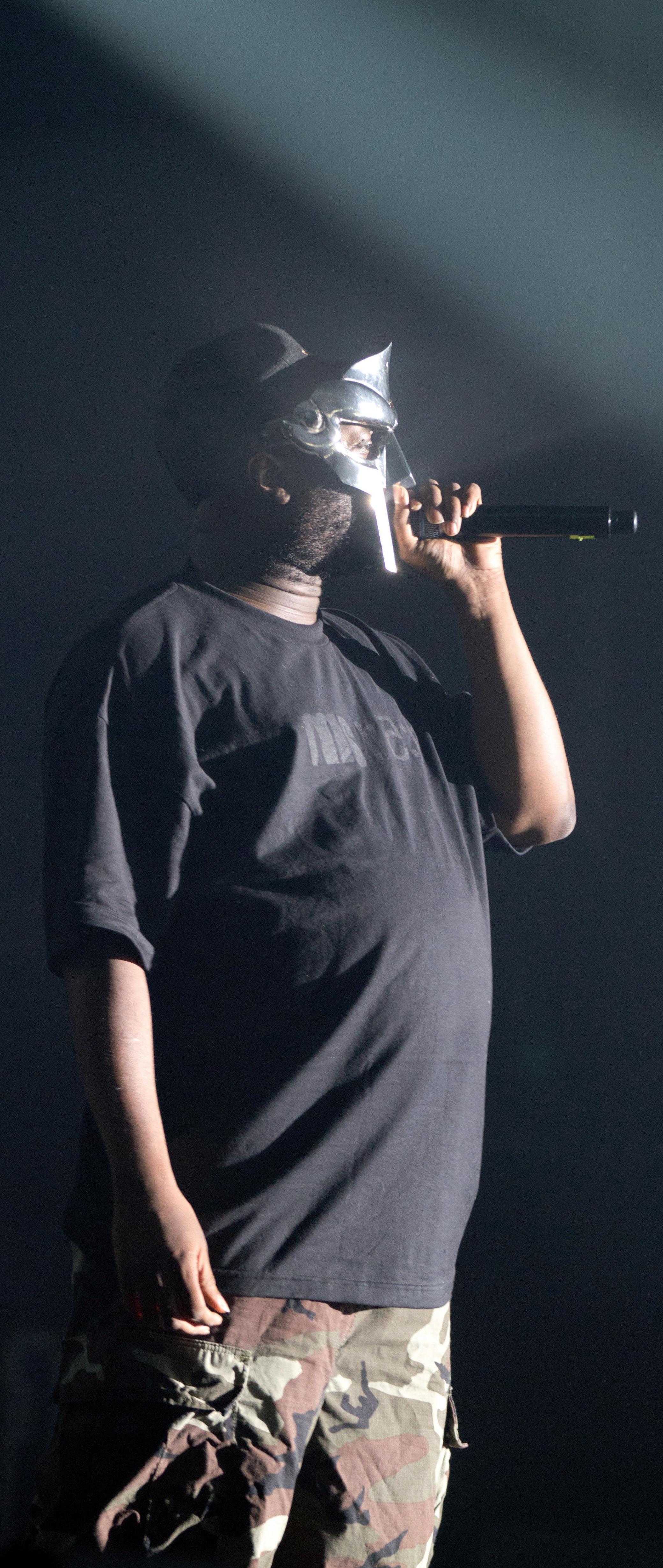

MF DOOM ENIGMATIC RAP RACONTEUR

By Oumar Saleh

By Oumar Saleh

Blessed with an ability to ‘order rappers for lunch and spit out the chain’, Daniel Dumile was one of the best to ever pick up the mic. M examines the man behind the MF DOOM mask to appraise the late London-born rapper’s hugely influential career, multiple personas and distinctive legacy.

M Magazine | 19

If you’ve been anywhere around Glasgow, London, Manchester or Leeds, chances are that you will have stumbled upon an MF DOOM mural. Featuring his name in all caps (like the man demanded) and his iconic metal mask, the vibrant artwork that reflects the technicolour oeuvre of the enigmatic rap raconteur has been sprawled across buildings, underpasses and bus stops since his untimely passing in October 2020. Considering that the London-born DOOM spent most of his life across the Atlantic, the UK graffiti dedicated to rap’s ultimate supervillain is testament to how much these shores embraced him.

Born on July 13, 1971 in Hounslow, Daniel Dumile and his family swiftly relocated to Long Beach, New York. Inspired by KRS-One and DJ Scott LaRock’s Boogie Down Productions, Dumile formed the hip hop group KMD along with his brother Dingilizwe. The siblings adopted new monikers (Dumile went by Zev Love X, while Dingilizwe became DJ Subroc) and quickly won fans with their effervescent 1991 debut record Mr. Hood, which balanced socially conscious raps with Sesame Street shoutouts. Tragedy struck, however, in April 1993 when Dingilizwe was killed in a car accident, aged 19. Compounding the misery, KMD were dropped by their label a year later, in part due to the latter’s reported objection to the incendiary cover art of KMD's second album Black Bastards, which featured the group’s 'Sambo' character hanging from a noose.

His spirit crushed by these overwhelming setbacks, Dumile vanished into obscurity for several years. Vowing to unleash revenge on the music industry that failed him, he began to invade open mic nights at Manhattan’s Nuyorican Poets Cafe with a stocking cap concealing his face; Zev Love X’s exuberant flow and idealistic witticisms replaced by a grizzled demeanour and grandiose ambitions. The cap soon gave way, though, to a metal face visage: spying a kindred spirit in the Fantastic Four’s archnemesis Viktor von Doom, whose origin story eerily resembled his own, these drastic creative shifts were the prelude to Dumile's final form as MF DOOM. As the antithesis to Puff Daddy and Bad Boy Records’ ‘jiggy rap’ that dominated the airwaves at the tail end of the ‘90s, MF DOOM’s debut LP Operation: Doomsday was a lopsided, disorienting masterpiece that forever changed underground rap. Juggling bleakly comic lyricism, wonky lo-fi beats and offbeat samples (ranging from ‘60s cartoons to old-school monster movies), Operation: Doomsday was heralded upon its 1999 release as a future cult classic.

Radiohead frontman Thom Yorke practically hailed DOOM as rap’s James Joyce.

What followed Operation: Doomsday is the stuff of legend. DOOM ushered in the new millennium by releasing a host of projects over a 17-month span from 2003-04, introducing the world to an ensemble of artistic personas in the process. In June 2003 he dropped the distorted space concept odyssey Take Me to Your Leader as the three-headed King Geedorah, an intergalactic horror straight out of the Godzilla Monsterverse. As cocky hoodlum Viktor Vaughn, he assumed another fearless alter ego that cared for little outside of trapping and time travelling on September 2003’s compelling Vaudeville Villain — a grittier, grimier album compared to its predecessors.

Most notably, MF DOOM starred alongside his musical soulmate Madlib on March 2004’s Madvillainy, considered by many to be both the rapper and producer’s magnum opus. Joining forces as Madvillain, the duo combined stoner rap aesthetics, obscure comic book references and avant-garde soundscapes to create one of this century’s most innovative albums. Overcoming a leak that occurred a few months before the record officially dropped, Madvillain justified the hype that preceded the final re-recorded version as DOOM’s lyrical chops were enhanced by Madlib’s pristine production that deftly toed the line between soulful and spaced-out. Even the subject matter went to another stratosphere, with both DOOM and Madlib’s alter egos making memorable appearances: the raucous America’s Most Blunted saw Madlib face off against Quasimoto, while Vik Vaughn’s romantic laments on Fancy Clown became renowned as rap’s first-ever self-diss track.

a tantalising preview of their planned DOOMSTARKS album, which sadly never came to fruition. Other notable collaborations, however, did materialise: DOOM’s dense discography includes fruitful partnerships with the likes of Gorillaz, BadBadNotGood, Czarface, The Avalanches and Westside Gunn.

Away from the music, Dumile faced an ultimately unresolved battle to return to the US after he was denied re-entry in 2010 following a European tour (in what was only his second international excursion as a touring musician). Despite never becoming a naturalised American citizen, he assumed that his American wife and five children would be enough to secure his return. However, not even a supervillain like MF DOOM could defeat the complex US immigration system, leaving Dumile to vow that he was 'done with the United States'. After proudly proclaiming in a BBC Radio 1 interview in 2012 that he was finally in possession of ‘the right colour passport', he quickly set about adopting British customs in his music, gleefully referencing the Cockney accent (‘hello, guvnor!’) and vintage UK TV in August 2012’s Key to the Kuffs, a collaborative album with abstract indie beatsmith Jneiro Jarel. Though isolated from family and friends at the time, Dumile’s enforced exile further exhibited DOOM’s skill in adapting to whatever challenges life threw at him.

DOOM’s next move? The November 2004 solo LP MM.. FOOD, a much more triumphant affair than his previous works. Beginning with the declaration 'Operation Doomsday is complete!', MM..FOOD was littered with the kind of absurdist musings and punchy multi-syllabics that went way beyond the ostensible edible-fuelled tributes to his favourite foods. Beef Rapp explored the collective obsession with clout years before social media engulfed the zeitgeist, while Deep Fried Frenz was a funky tribute to the true meaning of friendship.

After such a prolific run, DOOM’s next — and, as it would turn out, final — solo studio album arrived five years later with the Charles Bukowski-inspired Born Like This, which saw DOOM team up with fellow rap luminaries Raekwon, J Dilla and Ghostface Killah. Having previously worked together on projects like DOOM’s October 2005 collaborative album with Danger Mouse (The Mouse and The Mask), DOOM and Ghost’s off-kilter Angelz offered

Before he left this mortal realm, artists spanning numerous genres were quick to point out how DOOM had shaped their artistry and sound. Joey Bada$$ took inspiration from DOOM’s eclectic production on the Special Herbs beat tapes for his own debut record, while the oddball joie de vivre of Tyler, the Creator and Earl Sweatshirt quickly earmarked them as apt successors to DOOM’s Operation: Doomsday persona. Enamoured by how 'an entire album without hooks can sound so good', Danny Brown’s uncompromising style was directly influenced by Madvillainy. Well before he ascended as the world’s premier R&B crooner, The Weeknd’s early career mystique was clearly modelled after Dumile’s penchant for anonymity (while the mask worn on stage by the former during his recent After Hours til Dawn stadium tour seemed to be a direct homage to DOOM). Radiohead frontman Thom Yorke, who previously said that DOOM was his favourite rapper, practically hailed him as rap’s James Joyce by praising how he ‘would free-form his verses' like no one else.

In a weird way, it almost makes sense that Dumile’s passing at the age of 49 was announced two months after it actually happened in October 2020. After all, the man behind the metal face thrived in the shadows, going as far as to send in impostors to appear at gigs on his behalf during his peak years. Despite his ostentatious personas and often outlandish subject matter, MF DOOM was borne from a sad origin story of disillusionment at the music industry for discarding him so early on in his career. The outpouring of grief and heartfelt tributes upon his death becoming public knowledge only strengthened Dumile’s standing as a rap savant with incomparable pop culture acumen. There won’t be many after him to have such an iron-clad legacy.

M Magazine | 21

MF DOOM’s debut Operation: Doomsday was a lopsided, disorienting masterpiece that forever changed underground rap.

'What I really got from meeting these people who are now recognised as icons was how human they were.’

Hip hop’s visual historian

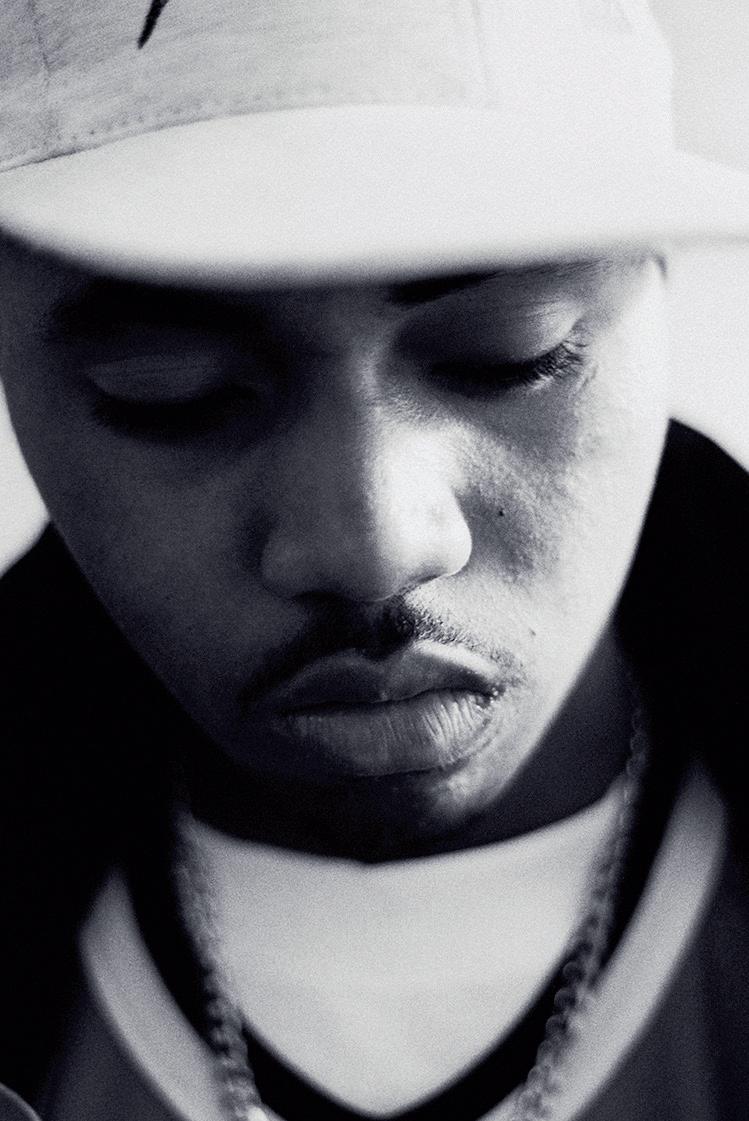

As he opens up his photographic archive of ‘90s hip hop legends, the UK photographer tells M about sitting down with Biggie, hanging out with Wu-Tang Clan and the biggest creative lessons he learned.

'I remember the first time I heard Main Source's Live At The Barbeque on the radio in 1991: everybody went nuts as it was the first time they’d ever heard Nas spit,’ Tee Max tells M as he casts his mind back to the first time he heard the New York rap legend, who he would photograph three years later. ‘Nobody knew who this kid was. When he came to the UK to do press for the first time, some of Illmatic had been played on the radio. But did I know he was going to be going to become an icon? No, I was just a fan of the guy.’

It was, Tee continues, ‘the same thing’ when he encountered The Notorious B.I.G. ‘Biggie was somebody who had been played on the radio constantly; everybody was really looking forward to his debut, Ready To Die. So the opportunity to be able to sit in the same room with him, let alone take photographs, was amazing. But, back then, I was just a fan of the music: the things Biggie and Nas were saying, how they were coming across and the stories they were telling in their music hadn't been told in that way before. People take those things for granted now, but what they were doing in hip hop at the time was revolutionary.'

Armed with his trusty camera, Alder White — AKA Tee Max — was able to get up-close-and-personal with a host of hip hop and R&B legends throughout the ‘90s. Documenting the likes of OutKast, Beyoncé and Busta Rhymes in their formative days, the photographer amassed an impressive archive while simultaneously ‘discovering who I was as an individual, creativelyspeaking’. Having kept much of his work from this momentous time out of the public eye since withdrawing

By Sam Harteam Moore

from the scene at the turn of the millennium, Tee has only recently begun to share his candid and striking shots with the world through exhibitions such as The Ascension Years at Brixton’s Black Cultural Archives.

'It was about me being able to somewhat more dispassionately look back at what I’d done,’ he tells M about his newfound willingness to exhibit his work. ‘Even when I started taking photographs, the notion wasn't that I was going to be somebody taking images for a magazine or a record company: I just did it because I really loved doing it. When people were saying to me in the late ‘90s, "You should put these in a gallery": why the hell would anyone want to go see my work in a gallery? That's absurd. It took me another 10 years after that to actually get exhibited on a wall, and that was only because I really liked the space.

‘Fast forward to now: if you ask me whether or not my work should be in gallery spaces, hell yeah! It should be in all the major gallery spaces now. It’s been a journey.’

M caught up with Tee to get his memories of working in music photography during the ‘90s, the biggest lessons he’s learned as a creative and what it’s really like to hang out on a Wu-Tang Clan video shoot.

Your photography career started when your mother gave you a camera at the age of 11. When did you start to fuse your love of photography with music?

'I studied photography during sixth form, which taught me how to print, load and process film. I then started taking my camera out and going to live shows and outdoor

M Magazine | 23

Main image: Busta Rhymes photographed by Tee Max

events, like Notting Hill Carnival. It was always interesting how people reacted to you at these events when they saw you with a camera, because there weren't that many people with cameras at that time.’

Opportunities to shoot some big names started to materialise as your profile rose. How did these commissions typically come about?

‘The main purpose of these artists being in the UK was to do live shows, so record companies would see it as their opportunity to get some press behind each artist. I’d get sent to the hotels they were staying at around London, and I’d either be in a hotel room, or the foyer, making the best of whatever I've got, which added another level of complexity to it because, for the most part, hotel rooms are not very attractive. It was really frustrating sometimes because you want to be more creative, but you have a certain amount of time on a certain day and that was pretty much it because the artists are only in the country for as long as it took them to do the show and then be on a plane to wherever else they're going.'

Do you have any particular favourites from your photographic archive?

'It's tough, as there’s tonnes of images I’m really looking forward to getting out in the world at some point. The Biggie images are some of my favourites because, y'know, it's Biggie. I can say it now: it's a really strong image. I love the image I've got of Nas because it spoke to who I met that day specifically. Again, I'm expecting a really braggadocious individual, but what I'm getting is a very introspective young man — and I got that in the image. One of my favourite images compositionally is Da Brat, just because of how she's posed [and] the depth of field is really nice.

‘I've got a shot of Keith Murray that I love because there must have been five or six other photographers in the room with me. We all had to get photographs somehow, and you're not usually in that kind of situation where there's literally somebody over your shoulder watching what you're doing. But the image I

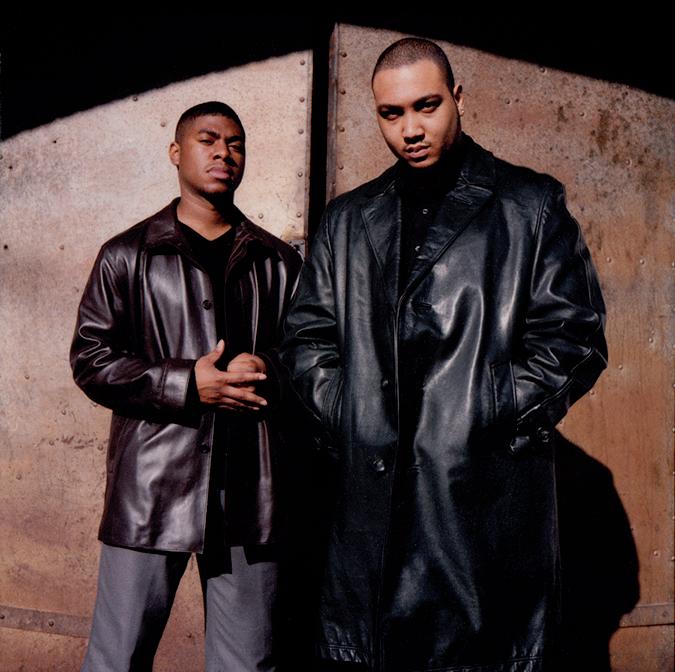

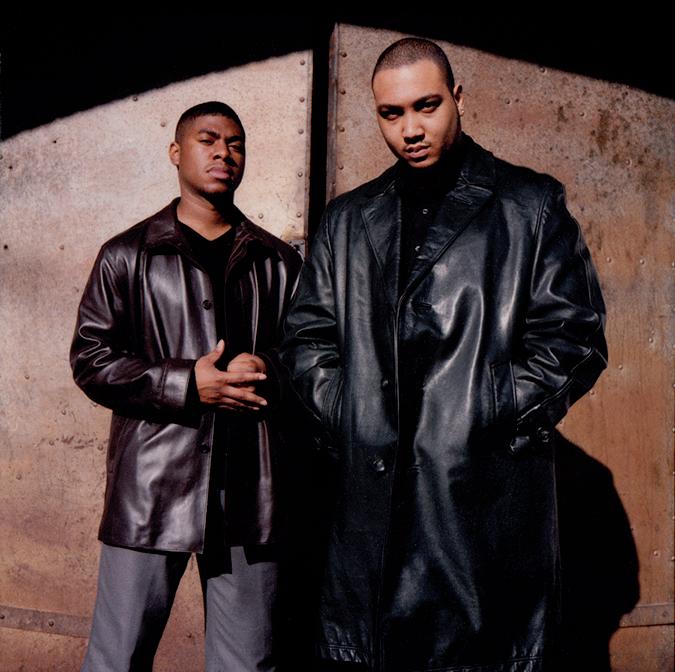

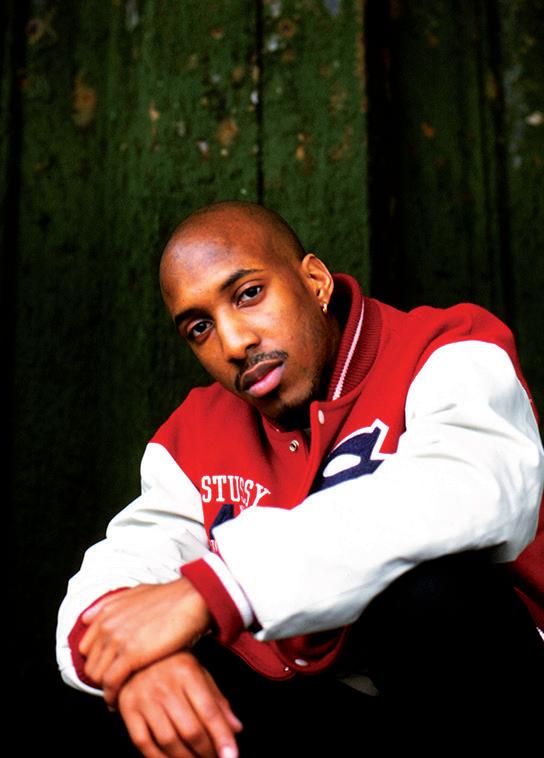

This page pictured from top L-R: Fallacy & Fusion; Mary J Blige; LL Cool J; Shortee Blitz and TY

Opposite: Method Man

All photos by Tee Max

M Magazine | 25

‘I really thought Method Man hated my guts, but he was just messing with me — we got the best interview footage ever.’

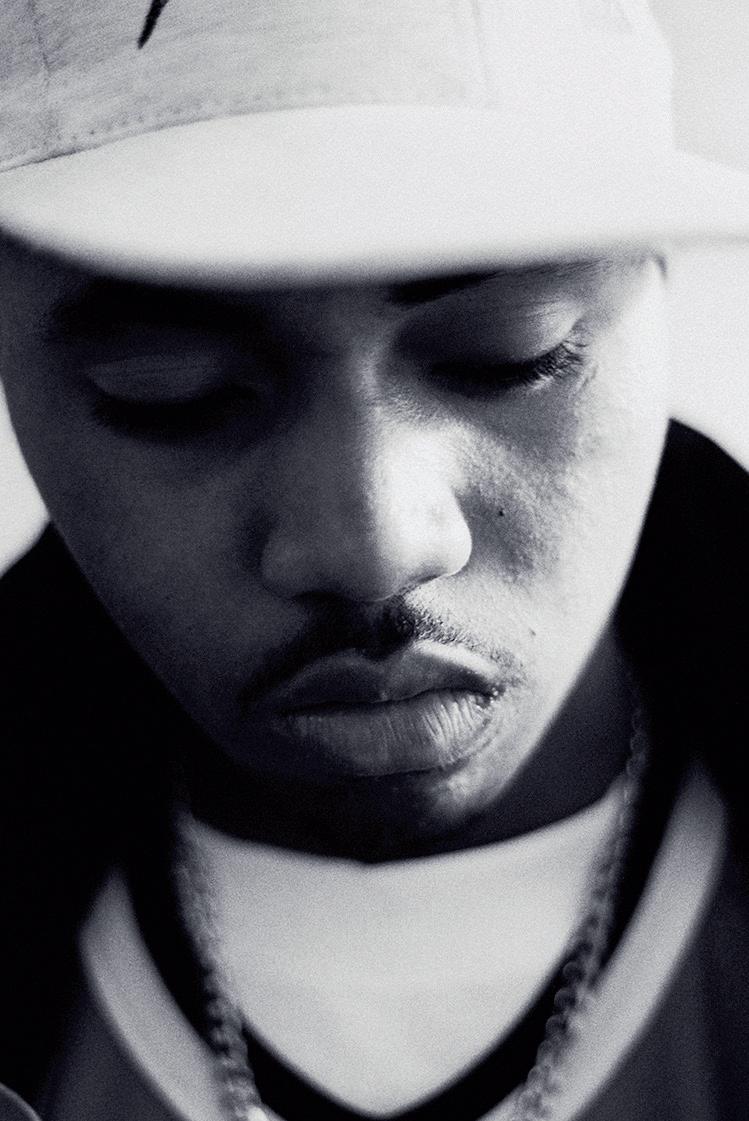

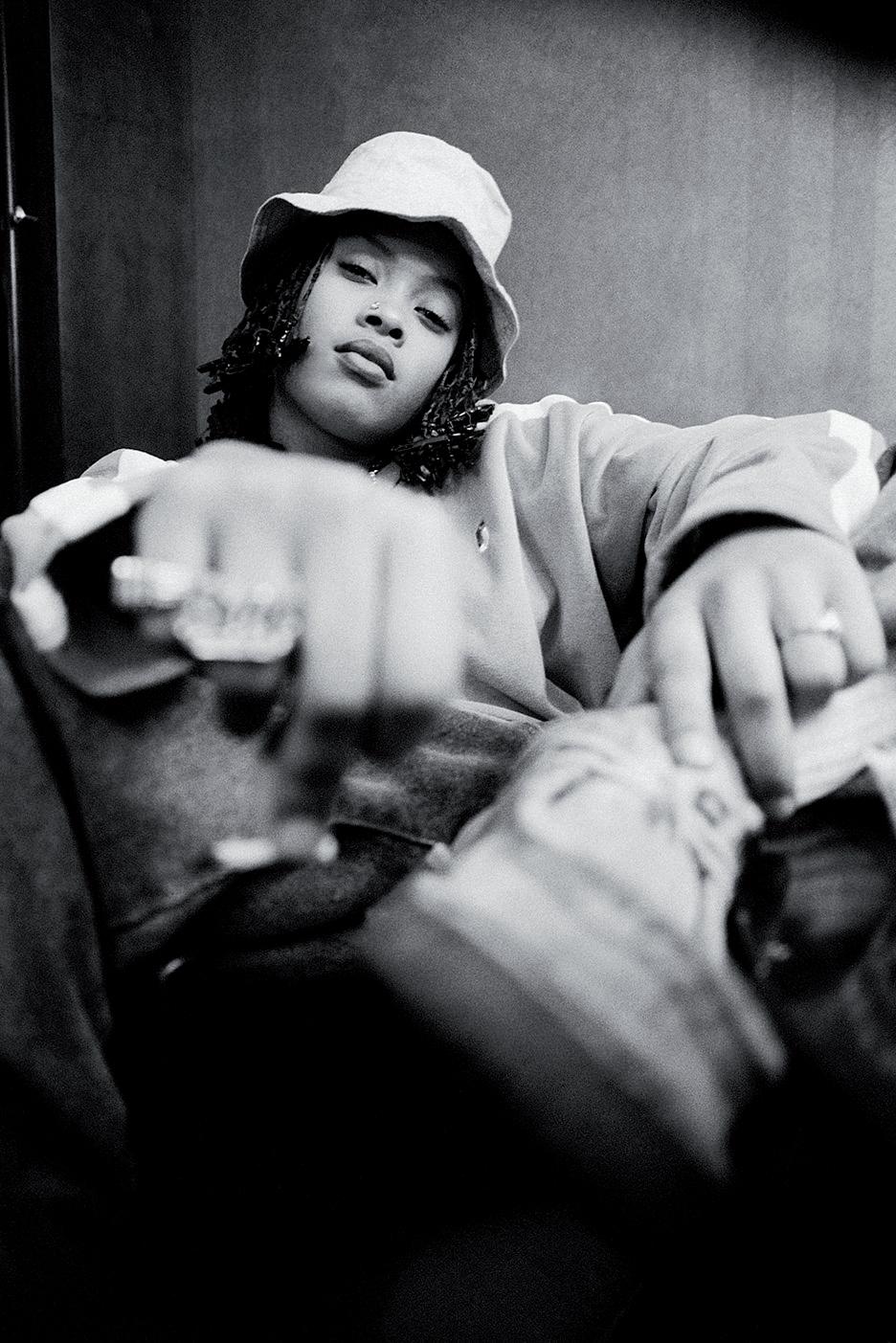

This page pictured from top L-R: Da Brat; Skinnyman; Maxie Priest; Nas; Shy FX

Opposite: Coolio

All photos by Tee Max

‘What the likes of Biggie and Nas were doing in hip hop in the early ‘90s was revolutionary.’

got from it, I really love. What that experience taught me was that it doesn't matter who else is in a room, because they're going to see things in different ways and have different things to achieve. I hadn't been in that situation before, and it taught me that it's all about what you see and how you get that image that you believe is gonna be the one.’

Some of your best work was taken on the set of Wu-Tang Clan’s video for Gravel Pit. How did that experience come about?

'Me and my friend Fusion — Alain Clapham — were working on a show for MTV Base at the time, an opportunity we’d been given completely out of the blue. Our senior producer told us that they had some extra money in the budget, so we pitched to go to LA and found out that Wu-Tang Clan were doing a video shoot there. By the time we got to the shoot it was approaching 120 degrees, and Wu-Tang are all there in their furry, Flintstones-esque costumes: all very regular!

'I had the best interview with Method Man: I really hope one day people get to see it again, because he was not compos mentis at the time completely, but it was a lot of fun. I really thought he hated my guts at the time, but he was actually just messing with me and we got the best interview footage ever. It was so much fun, and I got a couple of nice shots out of it as well. By that time I'd actually taken a break from shooting, but for some reason I decided to take my camera out there, and I'm really glad I did.’

What were the biggest lessons you learned from being a photographer during this era?

'What I really got from meeting these people who are now recognised as icons was — and it sounds really weird — how human they were. They were all very different. We want to homogenise experiences via the little bit of information that we get; the nuance of who you are as an individual isn’t something you're privy to for obvious reasons. Nas was a prime example: listening to Live At The Barbeque, which was him saying quite provocative stuff, you're then expecting this Queensbridge MC with all of that bravado to be sitting in front of you. What I actually got, though, was a really quiet, introspective 19/20-year-old, and it was intriguing.

‘It really illustrated to me that you have to be open to that human element of things. It was the ‘90s and it was very easy to pigeonhole people, particularly when it came to young Black men talking about things that are very viscerally challenging in terms of their lifestyle, the things they see and how they perceive and put things across. If you're not of that world or mindset and you're coming from somewhere completely different, it's a very challenging thing to hear and listen to. For the most part, it just seems either too incredible or too traumatising. There was that juxtaposition between somebody who's been brought up in the projects, where they're seeing

real world, first-hand accounts of simply being able to survive in a very real way, and a Black kid who lived in the suburbs in a predominantly very white middle-class area. These two worlds are worlds apart, but in the culture and dialogue that's being expressed through music, there was now a window to see what that individual sees. It's just allowing people the space to be able to be human.'

M Magazine | 27

Tee Max photographed by Ahmed Akasha

‘When Dave took to the piano at the 2020 BRIT Awards and branded then-Prime Minister Boris Johnson “a real racist”, the news cycle ran for days.’

Photo: JM Enternational

By Will Pritchard

Photo: JM Enternational

By Will Pritchard

Rebellion runs through hip hop like the grooves on a 12-inch record. It’s impossible to unpick the sound’s defining characteristics from its liberational roots, which were built on samples of expressive, subversive jazz and funk tracks that mirrored the rhythmic structures of slave songs, themselves passed down from the cotton fields and the Underground Railroad to segregated public housing ghettos and the streets that snake out from them. US rappers and MCs have sailed over these beats for half a century and counting, speaking ignored truths to entrenched powers. This is just as true of the UK’s homegrown hip hop pioneers, who wove their own narratives of struggle and release through a tapestry of US-inspired sampling and postWindrush sound system culture.

It was the early 1980s when David Emmanuel, performing under his Smiley Culture stage name, began experimenting with a ‘fast chat’ style of reggae toasting over the scooped bass bins of the Saxon Studio International sound system. In a manner that mirrored his boom-bap counterparts in the boroughs of New York, he found slim pockets between the rumbling dub basslines and clattering hi-hats and snares to fill with his whipsmart observations about life as a Jamaican in south east London. His 1984 debut single Cockney Translation offered a guide to East End dialect, swapping cockney offhands for patois aphorisms and foreshadowing the 21st century’s boom in multicultural London English in the process.

But laced in with Smiley’s cheeky chappy persona were stark stories about the realities of the prejudice Black people living in the UK faced at the time. His second hit single Police Officer, also released in 1984, recounted a common instance of police harassment: Smiley is pulled over by the cops, but the story takes a turn as the policeman hassling Smiley eventually recognises him (‘You what? Did you do that record, Cockney Translator?’) and requests an autograph in return for letting him go.

M Magazine | 29

From Smiley Culture calling out everyday prejudice on Police Officer to Stormzy verbally targeting a Prime Minister while headlining Glastonbury, UK hip hop artists have never been afraid to speak out. M explores the roots of the genre’s rebellious streak.

Some 27 years later, another encounter with police would end tragically for Smiley as he wound up dead during a raid on his home. An inquest returned a verdict of suicide, but Smiley’s family — who were never shown the report produced by the Independent Police Complaints Commission — have strongly disputed the finding.

While Smiley’s music in the 1980s was released against the backdrop of race riots in south London, sparked by heavy-handed policing of the Black community in Brixton, his death — and the suspicious circumstances surrounding it — would add tinder to a fresh pile of tensions years later that would ignite with the shooting of Mark Duggan by police in 2011. London, Birmingham, Bristol, Coventry, Derby, Leicester, Liverpool, Manchester and Nottingham burned through a summer of what was the most significant stretch of civil unrest in modern British history.

( Council Estate Of Mind ) built cult followings with their unfiltered visions of the lives of the overlooked, underserved and discriminated-against. Despite a common tendency among the wider public, and those in power, to dismiss rappers as either dangerous or clownish, over time their voices — and audiences — have grown to the point of being unignorable. By 2017, grime MCs were being sought out to rally votes, under the somewhat clunky #Grime4Corbyn banner, for a shift in the political status quo. When Dave took to the piano at the 2020 BRIT Awards and branded then-Prime Minister Boris Johnson ‘a real racist', the news cycle ran for days.

The distinctly Black British meld of sound system delivery and forthright, observational lyricism plied by the likes of Smiley Culture and contemporaries like Tippa Irie and Maxi Priest would be picked up by 1980s UK hip hop crews like London Posse, Cookie Crew and Demon Boyz. Their songs balanced braggadocio with brotherhood that extended across borders, while throwing off the fauxAmerican accents that, until then, were commonplace among homegrown British hip hop artists. In the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, the Black Rhyme Organisation to Help Equal Rights (or B.R.O.T.H.E.R.) supergroup brought together rap acts and reggae MCs for a string of releases protesting apartheid policies in South Africa and innercity gun crime, while also raising funds for sickle cell anaemia research. When groups like N.W.A. and Public Enemy brought their brands of firebrand rap activism to UK shores, it was the likes of London Posse they brought along to tour with them.

These early forays would ultimately lay the foundation for the many future iterations of underground UK hip hop culture — and the activist helix in its DNA would continue to be passed down as subsequent generations of beatmakers and rappers produced new evolutions. By the mid-'00s, rappers like Akala and Lowkey had taken up political loudhailers, while the likes of Klashnekoff (with his debut album The Sagas Of… ) and Skinnyman

For all those artists taking the fight to political powerbearers, there are just as many UK rappers who’ve found success and then turned their attention more directly to their communities. Not content with dropping their backto-back 7 Days and 7 Nights mixtapes in 2017, Croydon duo Krept & Konan established a youth work project, The Positive Direction Foundation, at the secondary school Krept himself had attended, providing working-class kids in their neighbourhood with access to creative workshops and the chance to expand their horizons. Before his death in 2022, SB.TV founder Jamal Edwards established a network of youth centres, with the similar aim of plugging a gap in youth service provisions following more than a decade of government-led cuts to the sector. Road rapper Nines took an even more direct approach to supporting his community: handing out hundreds of Christmas turkeys to his Church Road estate neighbours while filming the video for his mixtape hit My Hood in 2011.

Given the linguistic dexterity required of the form, it’s hardly surprising to see hip hop artists’ words proving so potent. For some, this has extended beyond the recording booth. Akala’s charisma and ability to articulate complex ideas of class, race, colonialism and structures of oppression — and to do so in way that is not only informative, but invigorating — has made him something of a modern-day apostle. While his ideas were laid out in thorough, practical detail in his 2019 polemic memoir Natives, they’re arguably most widely known from a clip of him dismantling Stephen Yaxley-Lennon (better known as EDL founder Tommy Robinson) during a 2013 episode of the BBC Three debate show Free Speech — footage which does the rounds with reassuring regularity.

As a growing handful of UK MCs have begun to achieve household name status, their role as advocates — and agitators — has only become more significant. Stormzy has used his profile (and deep pockets) to fund everything from a publishing imprint focused on supporting writers from under-represented communities to Cambridge scholarships for Black students. And when actions alone won’t suffice, he’s proven adept at picking his moments

‘As UK MCs have begun to achieve household name status, their role as advocates has only become more significant.’

to make his voice heard: be it calling out the government’s response to the Grenfell disaster while performing on stage at the 2018 BRITs, donning a symbolic Union Jackstreaked stab vest for his Glastonbury headline slot, or saving a tee-up call-and-response line on his 2019 hit Vossi Bop for a since-disgraced former Prime Minister (‘Fuck the government, and fuck Boris’).

Yet despite being a fixture of contemporary popular culture, homegrown UK hip hop is still forced to strive against every odd. In recent years, MCs have found themselves being forced to defend their artistry against heavy-handed attempts at state censorship, including the use of terrorist legislation to restrict how acts can

release and perform their music. Rap lyrics have an increasing presence in criminal court rooms in the UK too, where they’re used to prove guilt or propensity for serious criminality. These developments reflect not only a latent prejudice against Black art forms, but a broader misunderstanding of the communities they grow from — and presents yet another front for activist-minded artists to fight on.

But history, and all the fight and fervour that comes with it, is firmly on the side of hip hop here. As more fans and followers come to learn of the genre’s radical, resistant roots, it’ll be their voices joining in to demand a more vibrant, undeniable and fairer future.

M Magazine | 31

'History, and all the fight and fervour that comes with it, is firmly on the side of hip hop.’

Smiley Culture

Powering up PRS Foundation:

PRS Foundation has been investing in the future of UK music for nearly 25 years. Having previously supported the likes of Little Simz and Dave, the organisation’s focus on championing hip hop music creators has never been greater than it is today.

By Sam Harteam Moore

As the UK’s leading charitable funder of new music and talent development, the PRS for Music funded organisation has proactively supported some of the country’s most talented music creators. This is particularly true when it comes to UK hip hop artists, with the likes of Little Simz, Dave and AJ Tracey all receiving support from the Foundation at crucial stages in their careers. Vital talent programmes like POWER UP and the Hitmaker Fund, meanwhile, are ensuring that budding creators in the genre and beyond are receiving the necessary funding they need to take their creativity to the next level.

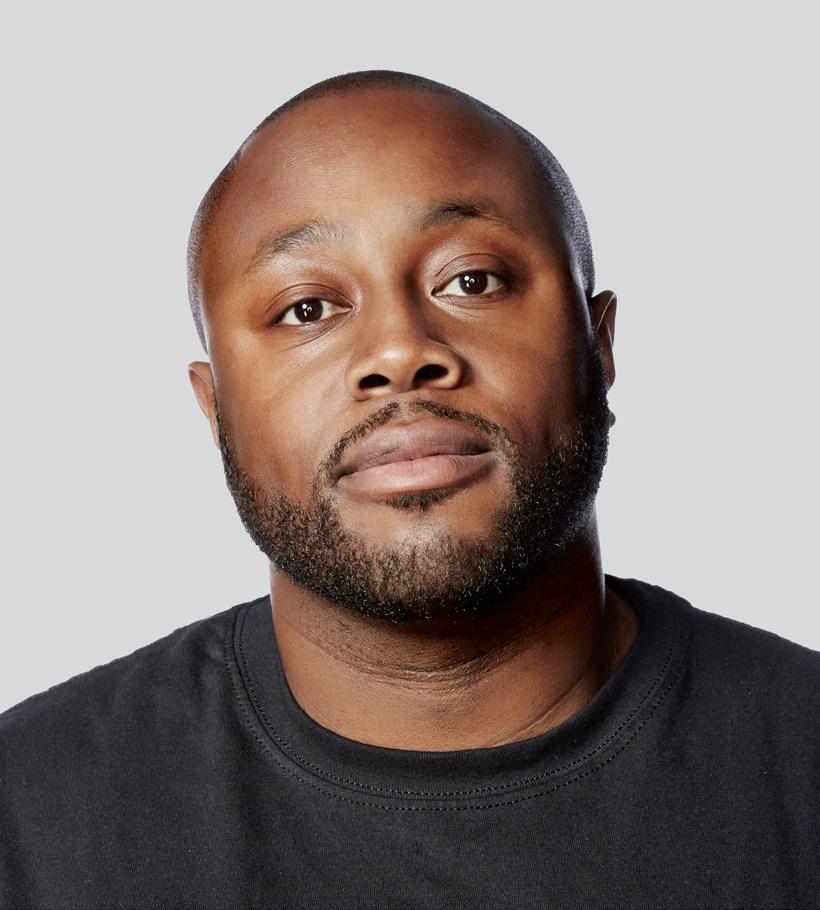

M spoke to PRS Foundation CEO Joe Frankland and POWER UP manager Yaw Owusu to find out more about the Foundation’s continued support of UK hip hop.

How would you describe PRS Foundation’s relationship with UK hip hop?

Joe Frankland: ‘We pride ourselves on offering timely support to exciting new music creators across the UK. Through the expertise of our team, independent advisors and

industry-wide partnerships, we have a strong track record for supporting hip hop artists, songwriters and producers. For decades, creators working in hip hop and associated genres have been pushing musical boundaries and building on varied influences while constantly evolving the sound and pioneering new ways to create music and reach new audiences. In a musical and business sense, the innovation within these genres is mind-blowing: over the last 50 years, the evolution of the industry and the way in which creators and industry professionals work has been hugely influenced by hip hop. This is particularly true in the UK, which has witnessed the arrival of genres like UK rap, grime and drill.

‘However, it’s safe to say that within the grant-making sector and during the Foundation’s early years, hip hop music, and creators working in its associated genres, were not receiving a representative share of grant support. I consider a big part of PRS Foundation’s overall role to be to reflect what’s happening in creative scenes, ensuring that financial and other talent development support is available and helps to nurture and impact the careers of music creators in all

M Magazine | 33

genres. I’m proud that, in recent years, over 10% of the music creators and organisations we fund work primarily in hip hop and rap genres — and over 20% work in Black music genres, including hip hop — better reflecting what’s happening creatively and commercially in the UK. The shift in the last 10 or so years has been huge. I expect this trend to continue and look forward to supporting more incredible members working in hip hop in the coming years.’

Who have been some of the best success stories from this relationship, and why?

Joe: ‘Our funding and support is reaching and helping so many UK artists, writers and producers, it’s hard to pick just a few. But we’re very proud to have supported members at crucial points in their journey including Little Simz, Dave, Bugzy Malone, Ms Banks, Mace the Great, Sanity, Young Fathers and AJ Tracey. Through programmes like the Hitmaker Fund, we’ve also been supporting behind-the-scenes creators like The FaNaTiX, Celetia Martin and Savannah Jada.

‘Many of these creators first accessed talent development support through non-profit organisations we fund, then accessed direct support through programmes such as the PPL Momentum Music Fund or the International Showcase Fund. Aside from being a huge fan of her music, that’s what jumps out to me about someone like Little Simz. She’s been supported by the likes of UD and Roundhouse, had grant support to take her first steps into the US through our International Showcase Fund and was supported earlier in her career through the Momentum Fund. Now she’s one of our country’s finest writers and performers and pays it forward in many ways.’

Yaw, what can you tell us about the work being done by POWER UP?

Yaw Owusu: ‘POWER UP is an ambitious, long-term initiative which supports Black music creators, industry professionals and executives, as well as addressing anti-Black racism and racial disparities in the music sector. As part of the development of this initiative, more than 80 Black music executives and creators came together through themed focus groups to contribute and steer the initiative. We then implemented a consistent strategy through the POWER UP Executive Steering Committee, which is made up of a cross-section of experienced and successful specialists in the areas in which we operate, including Keith Harris OBE, Paulette Long OBE, Ammo Talwar MBE, Sheryl Nwosu, Jackie Davidson MBE and Danny D. We also work with dozens of partners across the music industry including YouTube Music, Beggars Group and the Black Music Coalition.

‘Through our Participant Programme, POWER UP elevates exciting Black music creators and industry professionals and addresses barriers for those at crucial career stages. We cover all genres and are very proud of our work with an assortment of hip hop artists, including the likes of Guvna B, Bemz, Graft, Kasien and L E M F R E C K. We have also supported industry professionals who focus on platforming and developing the genre, such as Glasgow hip hop platform owner Sami Omar, Nottingham hip hop producer and promoter Joe Buhdha and studio owner James Ayo.

‘We are committed to supporting individuals who drive hip hop forward, both from a creative standpoint and in terms of infrastructure. We will continue to do so in the future, alongside our work across all genres.’

‘The PPL Momentum Music Fund helped progress my career as an artist massively.’

– Queen Millz

'I look forward to supporting more incredible members working in hip hop in the coming years.’

– Joe Frankland

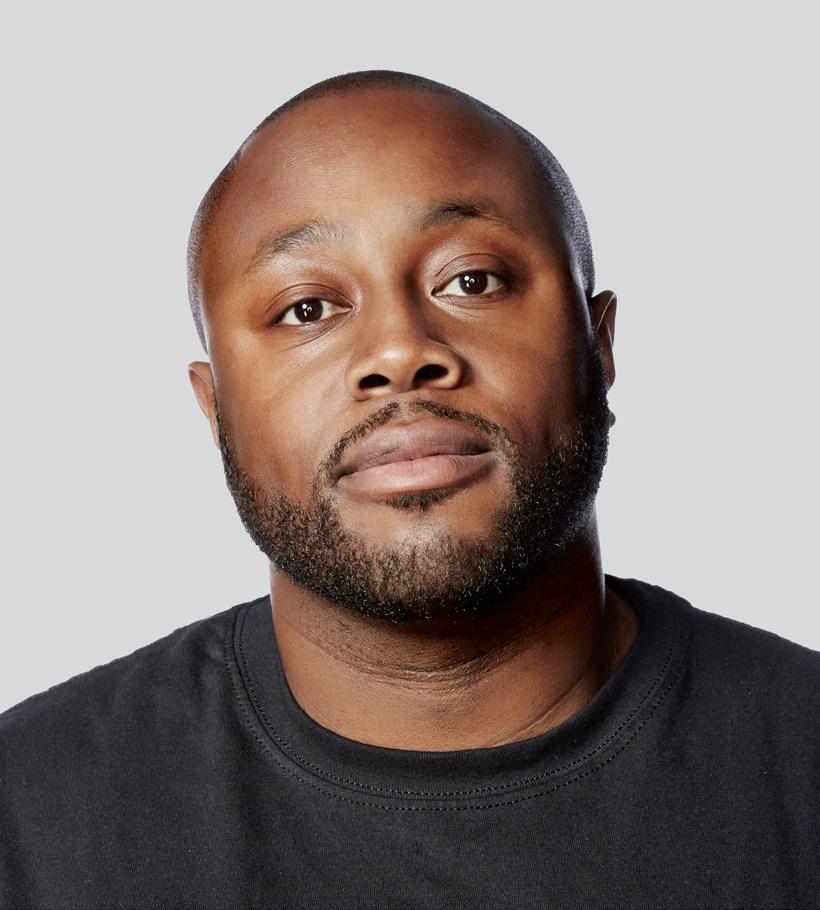

To get an artist’s perspective on the Foundation’s important work, M spoke to former Mercury Prize winner Speech Debelle (below right) — who is also a POWER UP creator and has been supported by the PPL Momentum Music Fund — and rising rapper Queen Millz (pictured left) has received grants from the PPL Momentum Music Fund and International Showcase Fund.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of hip hop. What does hip hop mean to you?

Speech Debelle: ‘It feels alive, like it’s a living entity. Imagine [if the] music came to us as artists to be heard. If that were the case, then we are listening to something that absolutely wanted and needed to be heard. Five decades really puts into prospective the conversations around the changes in hip hop, such as the emergence of mumble rap. How can anyone live to 50 and not evolve, change or experiment? 50 years old is an honour.’

Queen Millz: ‘Happy birthday hip hop! Growing up, I wasn't the best-behaved child. My parents put me into poetry workshops to guide my energy down a more productive path, and that led to me becoming a rapper/MC — so I thank hip hop for giving me a focus that has now turned into my career. Hip hop is the founding father of every genre that I ever touched: without hip hop, my sound wouldn’t be what it is today.’

How has hip hop influenced the UK music industry?

SD: ‘Jamaican culture was the catalyst for the birth of hip hop, and that was the case here in the UK as well. We went from wearing grey and brown clothing to colour clothing because of the Windrush era. So my first point of reference in terms of influence is actually Jamaica. Hip hop, though, has changed the music industry here hugely. Labels had to start [specific] departments and then have A&Rs of colour, and now the biggest stars in the UK are people of colour. Hip hop is forceful, proud and hypnotic.’

QM: ‘I think hip hop has influenced the UK massively: garage, rap, trap and grime have all stemmed from the hip hop sound. Hip hop has created careers for many people from underprivileged backgrounds in the UK to become successful.’

What are your hopes for the future of UK hip hop?

SD: ‘The women in UK rap are the most exciting currently. Whether musically like ENNY, Bree Runway and of course Little Simz, or the women within the industry like the A&Rs, managers and DJs. The future for UK rap is women-led. It's going to really shake the table when the UK music scene has its #MeToo movement.’

QM: ‘I hope that UK hip hop continues to grow, because it has come a long way to now be part of mainstream culture. I hope the underground can continue to flourish and make subgenres to develop the sound in different ways.’

You’ve both been supported in the past by the PRS Foundation-supported PPL Momentum Fund. How valuable was that support to you as an artist?

SD: ‘To be recognised as someone who deserves that kind of support is so important. I've contributed hugely to the scene both in front and behind the scenes, so it's like giving me my flowers. I'm completely independent, so I have to think about my budgets. I shouldn't have to use the money I make outside of music to support myself when it comes to releasing music. PRS funding is a way of making sure I don't have to.’

QM: ‘The Momentum Music Fund helped progress my career as an artist massively. It contributed to me releasing my debut mixtape Causing A Scene, and because of that I have been able to perform at festivals such as Reading & Leeds, Radio 1’s Big Weekend and SXSW — the latter of which was definitely one of my best experiences as an artist to date.’

Speech, you’re also a POWER UP Music Creator. Again, how valuable has that initiative been to your career?

SD: ‘Kinfolk: it’s really powerful to be in a WhatsApp group with people like Gaika and Josette Joseph. Our skills and talents are so varied, and POWER UP shows we can be so many things while also being Black. Helping us stay connected is crucial to surviving the kind of tactics a place like the UK has against us. How can you pit us against each other when we can just pick up the phone?’

M Magazine | 35

‘We are committed to supporting individuals who drive hip hop forward.’

– Yaw Owusu

Journalist and author Grant Brydon shares a selection of the life lessons he’s learned from pursuing his passion for hip hop.

Hip hop is many things to many people: a culture, a lifestyle, a music genre. At different times in my life, it has been all the above. But as I reflect on the effect it’s had on me, my peers and the hundreds of artists I’ve interviewed throughout my career, I see it as something far bigger. The most accurate way I can describe hip hop’s impact? It’s a force for personal development.

In his theory of person-centred therapy, pioneering psychotherapist Carl Rogers talked about the concept of the actualising tendency: his belief that, given the right conditions, we tend towards achieving our potential. I can’t help but see a parallel with hip hop, a creative movement that has motivated and enabled so many to use what is available to them in order to transcend toward something much larger.

Hip hop reminds us that our personal stories matter. Generally narrated in the first person, the lyrics permit us entry into the inner world of its creators: the life experience of an artist in one locality can be transmitted to listeners across the world. By hearing these thought processes and personal perspectives we're then able to empathise with a huge variety of different life experiences, as well as find the words, metaphors and references that can help us make sense of our own. As Jay-Z wrote in his 2010 book Decoded: 'Slick Rick taught me that not only can rap be emotionally expressive, it can even express those feelings that you can’t really name — which was important for me, and a lot of kids like me, who couldn’t really find the language to make sense of our feelings.’

While artists like Kendrick Lamar have recently started to bring the therapy room into full focus in their music (see last year’s Mr Morale & The Big Steppers ), hip hop has long possessed a therapeutic quality for creators and fans alike. The sincere words shared on record are not ones that often come up in casual conversation between friends — sometimes they may not even be raised with close family. But by writing so candidly, hip hop artists are able to help shape our lives as peers, mentors and role models.

I have endeavoured in my journalism to explore the creative processes of these artists, and, more often than not, I've learned something about myself. Perhaps the most significant of these instances occurred during an interview I conducted with J. Cole in 2014; a time when I was ensnared by hustle culture and toxic productivity. I was over-identifying with my line of work, which would have been a dream come true to my younger self, and yet I didn’t feel fulfilled.

Sitting across from Cole, who was days away from releasing his now-beloved third album 2014 Forest Hills Drive , our conversation turned to the subject of success. The rapper admitted that, time and again, he had expected his career goals to make him happy, only to then be let down. 'I didn’t want to worry about bills or anything financial, and I thought that would be happiness,' he said. 'I [then] got to a level where I don’t gotta worry about bills or anything financial, and I was like, “Wait, I ain’t happy yet?”

‘You’re doing something you love and you’re being productive in it by really getting out into the world and creating things you want to. That’s the joy, right there,'

‘Hip hop reminds us that our personal stories matter.’

Cole added, inadvertently turning the tables on our interview. ‘But by focusing on money that doesn’t exist, you’re not fully appreciating the blessings that you’re getting from your dream. It’s pulling you away from the moment. It’s steering you the wrong way.’

After this conversation, I started to realise that my profession had taken over my entire life. It’s easily done at the best of times, but for those of us who have made a career out of something we love and that we’d likely be doing anyway, the lines become increasingly blurry. It can be hard to recognise that we aren’t looking after ourselves: at times, it was difficult to remember why I was doing what I was doing in the first place. I was doing all the things I believed were necessary for a successful career, and I wanted to build my following and gain recognition: but what was it all for? I think that this is a vital question to repeatedly ask ourselves every time we feel a little lost in order to return to a sense of presence and intention.

In a recent interview I did with Joey Bada$$, he talked about the importance of knowing what our personal understanding of success is. ‘When you’re exposed to so much externally, it’s hard not to compare or

measure yourself against what's going on around you,’ he explained. ‘At the end of the day, there’s always going to be someone who is more advanced than you, or further on in life than you are. But that is no reason to measure up your own life or your own success, because everyone’s path is different.’

While it's easy to get swept up in the many metrics that attempt to quantify success, it’s more important to reflect on the personal significance of our actions and experiences. If you'd have asked me to define myself 10 years ago, I’d probably say I was a hip hop journalist. But by listening to the music more closely over the past decade, its true power has come into sharper focus: I now see how hip hop influences everything I do and who I am, holistically, as a writer, editor and person.

If there's one thing I hope you take away from this piece, it’s to consider your own potential, your own definition of success and your own sense of who you are. Hip hop, after all, teaches us to embrace and celebrate our uniqueness, not to follow the crowd.

Grant Brydon is the author of Life Lessons From Hip Hop, out now via DK/Penguin Random House.

M Magazine | 37

'Hip hop artists are able to help shape our lives as peers, mentors and role models.’

‘HIP HOP IS ABOUT COMMUNITY, SOLIDARITY AND THE MESSAGE’