5 minute read

Two Canal Pioneers.

Walking alongside the Chesterfield Canal, it’s easy to assume that it has always been here. It seems such an essential part of the landscape that one forgets it is an artificial waterway that only exists because of big decisions made by many people long ago. Rod Auton, tells us more.

Top image: 1959 Canoe Protest. Image IWA. This image: 1961 Protest Cruise at Shaw Lock.

Geoff Warnes

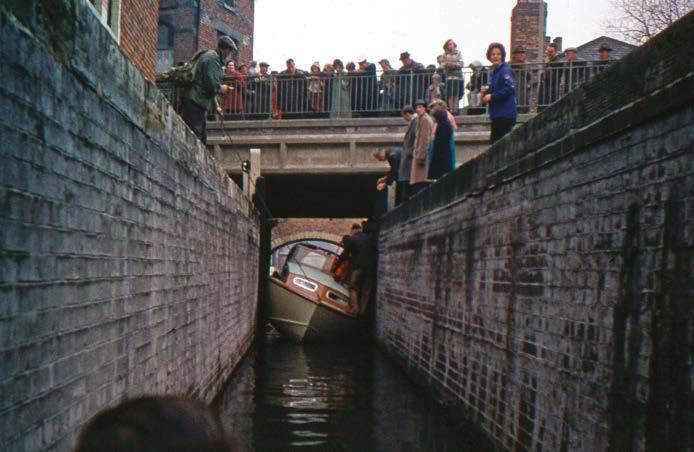

1962 protest cruise - Clifff Clarke's boat stuck in Worksop Town Lock.

Geoff Warnes

1963 narroboat Nelson at Manton Lodge.

Geoff Warnes

1962 protest cruise near West Retford lock.

Geoff Warnes

1962 protest cruise at Retford Aquaduct.

Geoff Warnes

1964 Rally at Drakeholes.

Geoff Warnes

The original idea for the canal was put forward by businessmen in and around Chesterfield. They wanted to find a more reliable and efficient way of moving their produce to other markets. Chief amongst these were heavy goods like lead, from the Peak District mines, and coal from Staveley and Killamarsh. By far the best way to carry such goods was by river, but the nearest port was Bawtry on the River Idle, over 30 miles away.

In the 1760s, such loads had to be carried by packhorses along turnpike roads that were often hopelessly muddy and virtually impassable for many months in winter.

The business community in Chesterfield heard about the newly built Bridgewater Canal which had enabled vast quantities of coal to be moved from the Duke of Bridgewater’s mines in Worsley to Manchester at great speed (for the time) and at low cost.

The engineer who designed the canal was James Brindley, a millwright from Derbyshire. It was therefore to Mr Brindley that the promoters turned. They were not alone, he was already involved in several other canal projects, none of which had yet been completed, so the whole concept was a very big risk.

James Brindley engaged another engineer, John Varley, who surveyed a route via Killamarsh and Shireoaks to Bawtry, which he presented in 1769.

News of the proposed canal soon became widespread and piqued the interest of people in Worksop and Retford. Chief amongst these was the Reverend Seth Ellis Stevenson, the Headmaster of Retford Grammar School. He had been to the Bridgewater Canal and saw the incredible potential for increased trade, and hence prosperity, for the town. He started a campaign to convince the great and the good in Retford that the canal should go through the town.

John Varley then surveyed another route, this time passing through Worksop and Retford and reaching the Trent at Stockwith, very close to where the Idle flowed into the Trent. This left Bawtry out in the cold.

There followed months of debates, meetings, proposals and counter proposals, with Revd. Stevenson always in the thick of it, travelling to meet people and entertaining them at his home, always putting Retford’s case. Finally, in January 1770, Brindley spoke to crowded meeting at the Crown Inn in Retford and announced that the route would be Chesterfield - Worksop - Retford - Stockwith. Retford had won the argument.

There was still much to do, such as lobby landowners and put together an Act of Parliament, but again Revd. Stevenson was always to the fore. Even after the Act had been passed and the work had started, he frequently visited construction sites, helped to sort out problems etc. The canal was officially opened on 4th June 1777, but in some respects the enterprise had only just started. The canal had to be made into an efficient, money making business. You can guess who was still in the thick of the action.

Let’s wind on nearly two centuries. In the intervening time, the canal had prospered and declined. It had been taken over by a railway company, which in turn had experienced takeovers and mergers ending up as the LNER. The Derbyshire section of the canal had been cut off by the collapse of the Norwood Tunnel in 1907. After the Second World War, the railway companies had been nationalised and canals had come under the British Transport Commission in 1947 and then the British Waterways Board in 1963.

Commercial transport on the canal had ceased in 1955. Whilst there was water, there was virtually no maintenance, so the lock gates were incredibly dodgy and the channel was full of weed. There were constant threats to abandon the canal completely. These were challenged by various different groups, both national and local.

Cliff Clarke receives his Lifetime Achievement Award from Robin Stonebridge.

Image courtesy of Chesterfield Canal Trust.

These groups used to hold protest cruises and rallies, sometimes with canoes and sometimes with boats. These were rarely the narrowboats we are used to seeing today, but usually small cabin cruisers. Because of the huge amounts of weed, they often had to be bow-hauled by groups of supporters on the towpath.

The key thing was to get lots of publicity at which these pioneers were incredibly adept. They even had local television news reporting on some of the protests which often drew large crowds of onlookers.

Whenever one speaks to any of the people involved in these cruises one name always comes up – Cliff Clarke. He was an inspirational figure who galvanised others by his own actions, who organised the nuts and bolts of many protests and who also lobbied, cajoled, enthused and argued at all levels - national, regional and local - to ensure that what was left of the canal was protected and restored. He helped to establish the Retford & Worksop Boat Club, which flourishes to this day, and became its first Chairman and later President.

The result of this constant campaigning was that the 1968 Transport Act stated that the twenty six miles of the canal between West Stockwith and Worksop was officially designated as a cruiseway. There were still twenty miles to Chesterfield to be restored, but the canal had been saved.

In 2010, Cliff received the first ever Lifetime Achievement Award from the Chesterfield Canal Trust. Upon the silver salver were inscribed the words “Without the tenacity of pioneers, there would be no canal.”

I would like to suggest that there are no two more important pioneers on the Chesterfield Canal than the Reverend Seth Ellis Stevenson and Clifford N Clarke.

Rod Auton

Rod is the Publicity Officer for the Chesterfield Canal Trust which is campaigning to complete the restoration of the canal by its 250th Anniversary in 2027. For further information go to www.chesterfield-canal-trust.org.uk.

Imagery courtesy of The Chesterfield Canal Trust (various photographers).