5 minute read

A wreck recovery on an epic scale

Recovering and removing the wreck of the Betelgeuse from where it lay by the oil terminal jetty was the largest and most complex recovery ever at the time

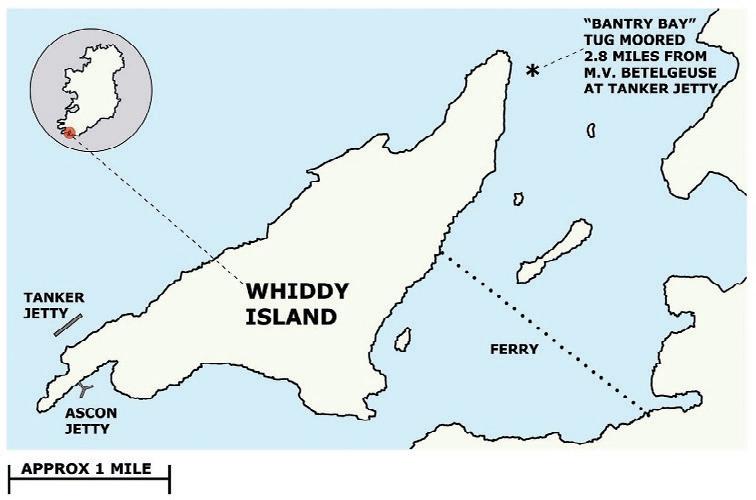

Whiddy Island in Bantry Bay, County Cork, Ireland, is the site of a major oil terminal with a jetty where vessels can discharge their cargo. That might not seem very unusual but Whiddy Island was also where one of the worst ever tanker wrecks occurred; a wreck that tested the ingenuity and capability of not only the salvage company whose job it was to salvage the wreck but also of a whole raft of firms in the oceanic engineering sector.

On January 8 1979, French Tanker Betelgeuse 61,766 tonnes gross and carrying 115,000 tonnes of crude oil, sustained two explosions while discharging cargo at the Whiddy Island terminal. The first explosion broke the ship in two with a second more powerful explosion following almost immediately. As soon as the news broke, Smit Tak International salvage company of Rotterdam set about the task of salvaging the stricken vessel sending the salvage vessel Barracuda to Bantry Bay where only the bow of the Betelgeuse was visible above the water with two thirds of the ship sunk in deep water next to the Jetty.

First Inspections

When the first inspection team went to the vessel, they found crude oil covering the decks and gas in the remaining tanks that threatened a further and worse explosion. To stabilise the fore section of the ship and to protect the jetty, a tow line was fixed from the fore section to a salvage tug. Thus began the largest wreck removal ever undertaken at the time and it was started while the condition of the sunken part of the ship was still unknown. All that was clear was that crude oil was leaking from the ship’s ruptured cargo tanks with all of the pollution threat that posed. So, oil booms were deployed to contain the leaked oil slick for a skimming vessel to collect.

Divers went down forty feet to examine the groaning hull and inform the tactics to be used in the salvage operation. This was dangerous work requiring expert diver skills. They found that the hull had broken into three sections with the aft section, including the engine room, sunk into 15 metres of mud. Taking advantage of the calm conditions, valves, hoses, high pressure hydraulic lines and special cargo safety pumps were deployed.

The Bow Section

Meanwhile, the divers continued their inspection of the wreck and discovered that the bow section was only lightly attached to the rest of the ship. Ballast pumps were used to adjusts the trim of that bow section and the tug prepared to attempt to tow it away from the jetty. However, that section was still entangled with the rest of the wreckage and so an alternative plan was put into action. The remaining crude oil in the bow section had first to be discharged but the wreck was 500 metres from the tank farm on Whiddy Island. A floating hose was rigged to pump the cargo to the oil terminal which lightened the bow section, minimised further pollution and saved 10,000 tonnes of cargo. When the crude oil had been pumped out, seawater was pumped in to break the bow section free. However, as the section broke loose, plates in the hull were ripped open, seawater rushed in and the section developed a dangerous list to port with the risk that it might flip over and into the jetty. Compressed air was pumped in to correct the list and bring the section under control: then the bow section was towed safely away, closing the first stage of the job.

THE MID-SECTION

It was decided to raise the mid-section using a combination of compressed air, shear legs and polystyrene spheres. But first, the crack splitting the mid-section from the aft would have to be completely cut through. Divers placed explosives to force apart the two remaining sections before also cutting access holes to get the polystyrene spheres into the hull and for the compressed air to escape during the raising. At the same time, divers also patched some other holes in the mid-section prior to pumping in the polystyrene and air. It was a tricky job at up to 40 metres depth in poor visibility.

Pumping the polystyrene into the mid-section continued for two weeks until the required buoyancy was achieved and a heavy anchor chain was used to saw through any remaining steel links between the mid- and stern sections. Divers went down to check whether the two remaining parts of the wreck had been separated and, finding that they had, then looped the chain under the mid-section to assist in the lifting. Air hoses were coupled for compressed air to be forced into the hull. Finally, seven months after the explosion, the mid-section was floated but because of the tanker’s draft and instability, a submersible pontoon was brough in to take the mid-section out of Bantry Bay. Water was pumped out to raise the mid-section as far as possible before the pontoon was submerged and the midsection towed into position.

The Aft Section

Now came the most difficult part; to deal with the aft section which weighed 7,500 tonnes. The weight was largely the heavy machinery in the engine room and, because the machinery filled the section, there was not enough space left to use the polystyrene method this time. It was decided to bring in four lifting barges with a combined lifting capacity of 11,000 tonnes but first, the 15 metres of mud into which the aft section had sunk had to be dredged away which took thirty days, removing 15,000 cubic metres of mud. Meanwhile, custom-designed equipment was being manufactured for the four hoisting barges on an unprecedented scale for any salvage operation. Even the hydraulic pulling machines were custom-made for this extraordinary lift.

Three sets of eight slings were pulled underneath the wreck and connected up again to the four lifting barges anchored in position above the aft section. The next job was to assemble the super-sized lifting tackle and gear on the lifting barges and then to ballast the barges prior to hoisting. Steel plates were lowered between the wreck and the cables to prevent the cables from biting into the weakened hull. Transducers were attached to the wreck by divers to register all movement during the lifting from 40 metres below the surface. The very, very slow lift began with the four barges carefully synchronised to avoid any risk of the wreck sliding out of the sling of cables lifting it.

Once the wreck was clear of the seabed, the barges, with the still submerged wreck suspended beneath them, were able to be moved away from the jetty and to a better position for the rest of the lift. The partially submerged wreck was towed by a team of tugs to a more sheltered anchorage where divers went down to patch cracks in the hull so that the engine room could be pumped dry to create more buoyancy. Pumps were lowered into the wreck and started to work until, slowly but surely, the combination of hoisting and pumping brought the wreckage to the surface and far enough out of the water for the final stage.

The semi-submersible pontoon was brought into position and sunk in 23 metres of water before, assisted by the tugs, the pontoon was positioned under the aft section and raised to bring the final part of the wreck out of the water more than a year and a half (573 days) after the explosion that wrecked the Betelgeuse in the largest wreck removal ever at the time.