16 minute read

ALFAS

Previous Spread

Italdesign’s Caimano was shown in 1971, based on a shortened Alfasud and with a combined windscreen and door canopy.

RIGHT Nicola Romeo was making these tractors when he took over ALFA. It’s sat with a 1980s AR148 off-road vehicle.

BELOW Not all the single-seaters are in the museum; this F1 177, Lola T9100 IndyCar and F3 car live in the store.

MUSEO ALFA ROMEO IN ARESE, MILAN, is beautifully laid out, with more than 70 cars over six floors. But behind the scenes is an attraction that is, for many, even better.

The storage rooms, over two storeys, are where the museum overspill is kept: more than 150 cars and 100 engines, prototype mechanical parts, trophies and models. It’s cramped and haphazard, a far cry from the main museum displays. But it’s utterly fascinating.

During the 2020 lockdown, the museum revealed the storerooms virtually via YouTube and social media. Now, tours are available every Saturday at 4pm for just €8 per person on top of the standard museum entry fee.

Many of the cars are concepts, prototypes, one-offs and competition machines. They include the Alfetta Spider and the Eagle, designed by Pininfarina in the 1970s, the Alfa Centauri prototype and the 177 that marked Alfa Romeo’s return to Formula 1 in 1979. You will also find the Pope’s car, a 164 Pro Car, the Nürburgring record 4C and much more.

Some of the models seem relatively run of the mill, but there’s always a reason they’ve been kept, whether it’s because they were the first, last or a unique specification.

“We like to collect something normal that is not normal,” says museum curator Lorenzo Ardizio, as he points out a GTV in a special shade of red chosen to make it ‘pop’ for TV.

If you are heading to Milan, don’t miss it. You need to book in advance by emailing collezione@museoalfaromeo.com.

ABOVE Of all the artefacts, it’s the oven that attracts most attention. Alfa Romeo built various utility items including ovens from 1944-46 to help it survive. We know from this one’s carderived chassis plate that it was the 63rd built, complete with two-burner hob, integrated kettle and electric oven. All were manufactured at the car factory.

OPPOSITE

The New York Taxi was a concept designed by Giugiaro at Italdesign in 1976 at the invitation of the New York Museum of Modern Art to create a cleaner, more efficient taxi. It featured flat floor space for wheelchairs, and sliding doors on both sides. It’s credited as a forerunner to the modern MPV. Next to it is Zagato’s 1983 Alfetta GTV6-based Zeta 6 concept.

LEFT The 158 and 159 Alfetta race cars dominated Voiturette and F1 racing from 1938-53. This 159 is sat next to a 1900 Sport Spider. Bertone was commissioned to develop two road cars – a spider and a coupé – with two of each produced in 1954. BELOW Full-size clay for the 8C supercar.

ABOVE These three are highly important: from left, we have the 1927 RL SS Mille Miglia that finished seventh overall and third in class in that year’s race; a 1939 6C 2500 Corsa; and a 1913 40/60HP similar to the one in which Enzo Ferrari made his Alfa racing debut. RIGHT The store is packed with styling and wind-tunnel models, many of which show interesting variations on designs that we now know so well. There are surprises, too – the Porsche 908 here, for example – along with Carlo Chiti’s fuel tank, the camera from the first Alfa Romeo crash test at Balocco test track, F1 bodywork, old measuring gear, wheels... it’s a true treasure trove.

RIGHT A scruffy early 1750 Berlina prototype in the store wears Rover badges, added by the factory to disguise its origins.

BELOW Alfa Romeo was trying out hybrid and electronic-control concepts in the 1970s, as these engines show. The result was the Alfa 33 Ibrida (hybrid), of which three were made. Behind is the SE 048SP Group C car, designed in secret to supersede Lancia’s LC2. Its 3.5-litre V10 was later replaced by a Ferrari V12. Sadly, it was never raced.

MORE THAN JUST CAR STORAGE

MORE THAN JUST CAR STORAGE

MORE THAN JUST CAR STORAGE

MORE THAN JUST CAR STORAGE

MORE THAN JUST CAR STORAGE

The Clubhouse at Henry’s Car Barn is a dedicated event space for luxury brands to curate exclusive events or launch moments in the heart of the country.

The Clubhouse at Henry’s Car Barn is a dedicated event space for luxury brands to curate exclusive events or launch moments in the heart of the country.

The Clubhouse at Henry’s Car Barn is a dedicated event space for luxury brands to curate exclusive events or launch moments in the heart of the country.

The Clubhouse at Henry’s Car Barn is a dedicated event space for luxury brands to curate exclusive events or launch moments in the heart of the country.

Find out more on our website.

Find out more on our website.

The Clubhouse at Henry’s Car Barn is a dedicated event space for luxury brands to curate exclusive events or launch moments in the heart of the country.

Find out more on our website.

Find out more on our website.

Find out more on our website.

WWW.HENRYSCARBARN.CO.UK

WWW.HENRYSCARBARN.CO.UK

WWW.HENRYSCARBARN.CO.UK

WWW.HENRYSCARBARN.CO.UK

WWW.HENRYSCARBARN.CO.UK

THE LITTLE VILLAGE OF TILFORD LIES on England’s Surrey/Hampshire border at the junction of two branches of the River Wey. Its steeply sloping local green is a famous venue for village cricket, and flanking that is the 17th-century Barley Mow pub.

Back in the 1950s, that hostelry was one of the favourite haunts of Mike Hawthorn, Formula 1’s first-ever British World Champion driver. Local stories of his boisterous nature remain rife. But I very much doubt if he would ever have realised that the last resting place of one of his pioneering predecessors was less than 350 yards away, across that village green.

For there, in the All Saints churchyard, a starkly rough-hewn granite headstone is inscribed: “In loving memory of Selwyn Francis Edge 12th February 1940 aged 71 and of his cousin Cecil Edge 27th July 1908 aged 28 also Myra Caroline Edge wife of SF Edge 18th March 1969 aged 82 years.”

The stone offers no clue to the uninitiated who these Edge family members might have been. But the moment I unwittingly stumbled across this monument only ten or 15 years ago – despite having lived locally for over 50 years – I recognised their names: SF Edge – Britain’s greatest and most significant pioneer motor racer, the first ever to win an international event in a British-built car, no less – his cousin, riding mechanic and fellow racing driver Cecil, and SF’s long-supportive second wife Myra.

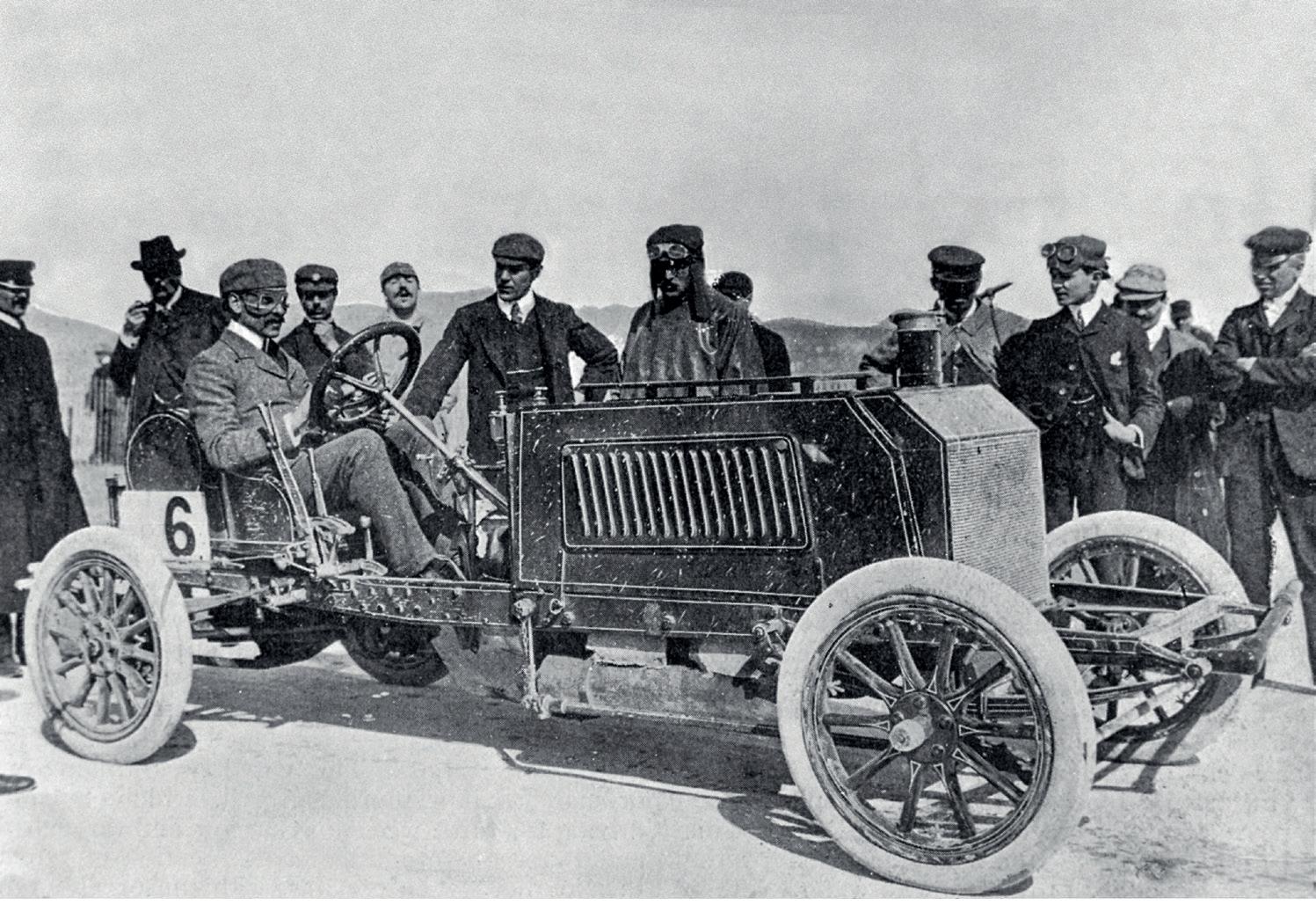

Edge’s most prestigious win came in the 1902 Gordon Bennett Cup race, driving a Napier over a punishing 387 miles of public roads from Paris, France to Innsbruck, Austria. Last year marked the 120th anniversary of that much-publicised success. And SF then became one of the leading proponents for having the Brooklands Motor Course built at Weybridge, Surrey – the world’s first significant tailormade circuit for motor-vehicle testing and competition. What’s more, he then promoted the brand-new venue’s opening by completing a record-breaking 24-hour drive there – again using a Napier – driving solo to complete 1581 miles 1310 yards in the day-long grind. That was an average of “65 miles 1594 yards” per hour in the prissily precise Edwardian style of the time.

Somehow it’s little surprise that such a flinty, apparent iron man as SF was actually Australian born, in Concord, New South Wales on March 29, 1868. His parents Alexander Ernest Edge and Annie Charlotte Sharp were from the comfortably well-off merchant class. He was the first-born of their seven children, and in 1871 Alexander moved the family to England, settling in Upper Norwood, South London.

SF was evidently a delicate child, strong neither physically nor academically, but he inherited his father’s shrewd merchant mindset and developed an interest in things mechanical. He was also headstrong and independent. He got into several boyhood scrapes – shooting prized birds with a catapult in Crystal Palace Park, and even setting off “an explosive device” in an elderly neighbour’s garden (case unproven, insufficient evidence). Being mentioned twice in the national press while still in his teens would lead his modern-day biographer Simon Fisher to suggest that “maybe this led to SF’s later addiction to seeing his name in print”.

Both his father and uncle Arthur were keen cyclists through the 1880s. SF tried one, too, and thrilled to speed. In 1884 he bought a Sparkbrook tricycle and joined the local Anerley Bicycle Club. He was still considered sickly, but his innately competitive and rebellious nature regarded cycling, hard and fast, as a passport to fitness – and self-assertion.

In August 1887 he won the Catford Cycling Club’s Westerham hillclimb. That October saw him and club-mate GL Morris pedal an Olympia tandem tricycle to a new 100-mile record, reaching the mark after 6hrs 57mins 32secs, more than nine minutes inside the previous mark. He cycled constantly, covering 7201 miles in 1887. He won on both road and track through 1888-89. Into 1890, one of cycling’s most celebrated challenges was to “go for a time” London-to-Brighton. SF went for it, riding a Marriott & Cooper safety bicycle to the south coast there, in 3hrs 18mins, then back again. He completed the entire distance in 7hrs 2mins 50secs – a new record by more than 16 minutes. That delicate kid had grown into a ferociously fit and focused athlete.

ABOVE SF set his first Brooklands 24-hour record in June 1907. His 60hp Napier completed over 1581 miles at an average of more than 65mph.

Hatchet faced, dark complexioned, with a florid black moustache and great beetling eyebrows above “disturbingly penetrating” dark-brown eyes, SF became in every way a commanding figure. In May 1891 he made his Continental road-racing debut, finishing third in France’s 385-mile Bordeaux-Paris event.

He earned his living as a commercial traveller, selling Marriott & Cooper bicycles, using his competition success as sales promotion. He again lowered the London-to-Brighton record in 1892, then the London-to-York – 197 miles. At a cycle race that year he met fellow competitor Montague Napier, heir to the D Napier & Son engineering business. He also met – and married – Eleanour Rose ‘Nellie’ Sharp, a near neighbour and herself a keen cyclist.

Meanwhile, he’d taken a managerial job with a new cycle manufacturer based in Glasgow, Scotland. Nellie spent time with him there, and when cycling locally she lagged behind him and was accosted by four young men, one of whom tried to kiss her. Wondering where she had got to, SF rode back, and when he heard what had happened he tore after the boys, produced a revolver and threatened to shoot them – earning himself a £5 fine from the local magistrates’ court. Never pick on an Aussie’s girlfriend…

Unimpressed by the Glasgow venture, SF quickly moved to join Rudge & Co in Coventry. There he met wealthy Harvey du Cros, promoter of Dunlop pneumatic tyres, who made him his racing manager, based back in London. By 1895, SF was increasingly fascinated by the potential of the new-fangled ‘horseless carriage’. He saw it as a coming craze, as an indispensable means of transport and as creating a colossal new market for pneumatic tyres.

A French acquaintance was fellow racing cyclist Fernand Charron, a kind of diminutive Alain Prost figure, who was running a Panhard, Peugeot and De Dion-Bouton agency in Paris. Edge visited, and Charron gave him his first ride on a motor car, a twin-cylinder 6hp Panhard.

Back in England, SF immediately became involved with British motoring pioneers Sir David Salomons, Harry Lawson and the Hon Evelyn Ellis. Edge began working on imported cars for Lawson’s British Motor Syndicate in Euston Road, London. He was 27, and there met 18-year-old fellow enthusiast Charles Jarrott. Together they learned the new technology. When HM Government passed its new Locomotives on Highways Act on November 14, 1896, Lawson’s infant Motor Car Club organised its ‘Emancipation’ Run from London to Brighton to celebrate the new freedoms conferred. SF followed the cars – on his bike.

In 1887 he talked Lawson into loaning him a powered De Dion-Bouton tricycle, which he drove to Canterbury and back. Highly impressed, he purchased one, plus a Bollée and a Motette – enjoying them so much, he wrote to new magazine The Autocar declaring: “It has almost made me give up cycling, as at present there is a good deal to be learnt in driving these cars. I have absolute faith that we shall see them running about in thousands in a few years’ time.”

Sheen House track organised by the Motor Car Club. On an Ariel tricycle – having become a director of that company – he won two races, over a mile and two miles respectively, the first from his friend Jarrott.

They both ordered 2¼hp De Dion-Bouton racing tricycles from the Parisian factory, and in May 1899 they contested the Paris-Bordeaux city-to-city race astride them, with little luck. Greater success followed in minor British events, while SF became disgruntled with the du Cros Dunlop business and spent time instead briefly involved with the Sunlight Incandescent Gas Mantle Company, while apparently studying the emergent British motor industry for a better berth.

He had bought from Harry Lawson the 6hp Panhard & Levassor ‘No 8’, which had finished second in the 1896 Paris-Marseille race. Through a mutual friend he re-made contact with engineer Montague Napier, who had designed a motor-car engine of his own, which Edge promptly critiqued. He asked Napier to try to convert the Panhard’s primitive tiller steering to wheel, and loved the result. He made further requests for Napier to improve the car, and the engineer then asked Edge if he could build a complete new engine for it, not least using electric-spark ignition in place of its obsolete hot-tube arrangement. SF was delighted by the new unit, and talked Harvey du Cros into financing Napier in laying down a new range of production cars, promising to buy them all – in effect to become Napier’s sales associate.

SF created the Motor Vehicle Company to promote and sell D Napier & Son’s new motor cars. When a Thousand Mile Trial routed through England and Scotland was organised for 1900, SF saw the ideal opportunity to promote his new venture. He drove his 9hp electric-ignition Napier from London to Edinburgh, then back to London – and won his class with the second-best performance

He became a founding member of the Automobile Club of Great Britain – forerunner of the RAC – in August 1897, and in 1898 he spectated at the Paris-Amsterdam road race for motor cars. He bought a four-wheeled Panhard, and competed in his first motorcycle race on November 14, 1898 – in an event at the GP overall. The first four-cylinder Napier followed, SF and his colleague Napier having discussed the possibility of building a vehicle capable of success in the international Gordon Bennett Cup team event due in 1901.

Their prototype car was first entered by SF in the July 1900 Paris-Toulouse race, with none other than the Hon Charles Stewart Rolls of future Rolls-Royce fame as his riding mechanic. Sadly the new car cracked a water jacket and they had to retire. Back home in the 1900-01 winter, SF’s combative nature resurfaced when on a drive down to Brighton he was hit on the head by a chunk of ice, lobbed by a pedestrian “country yokel”. Leaping down from the car he pursued the man, forced him to strip off his clothes and promptly drove off with them until he saw a group of “similar fellows”, to whom he handed his trophies, to be returned to his then-shivering – and crestfallen – assailant.

While the early legal requirement for motor cars on British roads to be preceded by a man carrying a red flag had been repealed, a national speed limit of 12mph still applied. Even in 1900 motor cars were capable – as today – of far exceeding the legal limit, as SF found in a police speed trap on the Brighton road in March 1901, which logged him driving at 22mph. Hiring an expensive lawyer won his case, plus £5 in costs.

Napier built him a special 50hp racing car for that year’s Gordon Bennett Cup in France, but SF had to contest only the concurrent ParisBordeaux race instead. Montague Napier accompanied him, yet their race ended in clutch failure. SF drove the massive, tyrehungry 50hp Napier again in the following Paris-Berlin, being timed at 69mph over a flying kilometre before being unsighted by the dust plume from a car he was trying to pass and clouting a bridge parapet. But class wins in a pair of home hillclimbs then preceded a successful trip to the major straight-line Gaillon hillclimb in France, in which he and the

Napier won their class, so humbling Panhard…

For 1902, Napier designed a new 6½-litre, 933kg (2056lb) shaft-driven racing car to contest the Gordon Bennett Cup race, run that year on the Paris-Innsbruck section of the great Paris-Vienna city-to-city race. SF took his cousin Cecil Edge with him as riding mechanic. The car was not completed until just seven days before the race start on June 26. En route to the Folkestone-Boulogne ferry it overheated. SF found one of the cylinder heads had cracked.

A replacement was rushed down by train to the ferry port, accompanied by two mechanics who fitted it during the sea voyage. In Paris, it was found that inadequately case-hardened second-gear teeth were bent. Overnight, Montague Napier and one of his mechanics repaired the damage at the Clément works. After scrutineering, Napier then realised that they had omitted to refit a gearbox spacer during the rebuild. The transmission had to be stripped and reworked, again overnight.

Edge made it to the startline just in time. Now, much was made then – and has been ever since – about the ‘legendary’ Gordon Bennett Cup races. They were open to national teams of only three cars each from interested motor-manufacturing countries. The French industry, at that time by far the world’s most diverse, saw this as unacceptably restrictive, and consequently would work towards a more liberal pinnacle competition, open to all – their Grand Prix. In that 1902 Gordon Bennett Cup, Edge’s Napier and the Wolseleys of GrahamWhite and Callan for Great Britain faced a full French team of René de Knyff’s Panhard, Henri Fournier’s Mors and Léonce Girardot’s CGV.

SF and Cecil happily found their new Napier running well on the opening stage, until a tyre punctured. After fitting a spare inner tube they were horrified to find their tyre pump not working to inflate it. SF flagged down the next car, Count Louis Zborowski’s Mercedes, to ask if he could borrow their pump. The Count simply gave it to them, selected first gear and tore off. They reached the initial night stop at Belfort, grabbing some much-needed sleep.

The good news was that their Gordon Bennett Cup rivals Girardot and Fournier were out; the bad news that the last-remaining French contestant, de Knyff, was leading the main event overall. Further issues arose when they went to the car next morning to find all four tyres were flat, so new tubes had to be fitted all round. For political reasons the following stage to Bregenz in Austria was neutralised, competition driving prohibited –so SF trundled the entire way in top gear.

Waking up in Bregenz they found all four tyres flat again, so their restart was preceded by the heavy manual labour of fitting fresh tubes. The climb of the punishing Arlberg Pass followed, with SF more concerned about the descent, for the Napier’s brakes were tiring rapidly. He likened the descent to “a flight of stairs”, with level stretches (intended to give carriage horses some rest) punctuating the slope. He feared the Napier’s springs or chassis would break every time they hit a level, and when they reached the bottom he and Cecil stopped to double-check the car, only to find that its entire rear bodywork had fallen off, taking their tools, spares and inner tubes with it.

But during the descent they had passed an abandoned Panhard. When Charles Jarrott and George du Cros, competing in the main race in the former’s Panhard, came by, they stopped with encouraging news. That abandoned Panhard had been de Knyff’s – their sole remaining Bennett Cup rival. If the Edge team could complete the 30 miles remaining to Innsbruck, victory would be theirs.

While they had lost their auxiliary inner tubes, there were still spare tyres strapped to the Napier. SF opted to fit them as a precaution to protect the hard-used inner tubes. But with neither jack nor tyre levers available, they had to claw the worn rubber from the rims, rolling the car forward a couple of inches with each wrenching, draining effort. But ultimately the Edges restarted, drove gently into Innsbruck – and won for the Automobile Club of Great Britain and Ireland that still-prestigious international Gordon Bennett Cup.

Since the ‘British parts only’ regulation of the Cup race was no longer relevant, SF then pressed on to the overall city-to-city race finish in Vienna, running French inner tubes –averaging 31.9mph for the entire distance, 15th overall and eighth in the Heavy Cars class.

Edge biographer Simon Fisher explains the curiously profound significance of the Cup win: “It put Britain on the map as a serious manufacturer of motor vehicles, which otherwise had been the preserve of the French, it gave Napier excellent publicity, and it made SF a national celebrity.”

This was something upon which Edge would build vigorously, competing on water as well as on land, and even flying a balloon to a claimed 35,000 feet from Berners Elms in Essex. In 1903 he drove in, and survived, the catastrophic Paris-Madrid race that saw cityto-city racing banned, and was part of the British team that lost its defence of the Gordon Bennett Cup at Athy, Ireland, to Camille Jenatzy’s Mercedes. He prevailed upon Montague Napier to build a six-cylinder engine, which proved notably smooth, and also raced Napier-engined power boats.

With the 1904 Bennett Cup race contested in Germany, SF headed Napier’s challenge, only for his car to fail. He regarded the team’s race performance that day, being beaten by Wolseley

– never mind Léon Théry’s outright-winning Richard-Brasier – as ignominious. He made that circuit race his last, although he continued to contest occasional sprints in England.

At the Bexhill Speed Trials of May 1907, five Napiers competed, SF setting a 73.77mph new course record while Cecil won another sprint in a 60hp Napier. Meanwhile, SF had been a friendly advisor upon construction of a custom ‘motor track’ on wealthy Hugh Locke King’s estate at Brooklands. Early on he declared an interest in booking the new course for an attempt to drive, solo, at 60mph “or better” for 24 hours.

In retrospect, Locke King – heir to a hotel family fortune – was not so much a visionary car and motor-racing enthusiast, but more somewhat naïve, and easily led. Far from costing him £22,000 as first estimated (for a flat, unbanked motor speedway), the highbanked Brooklands Motor Course finally cost him some £150,000. It virtually bankrupted him. And very few of his macho, thrusting, encouraging (but fleeting) Edwardian friends, SF amongst them, who had exploited his willingness to provide a stage upon which they could strut, would want to know when he emerged as a victim – his frail health broken.

Brooklands was opened on June 17, 1907, and SF booked it for his 24-hour record run on June 28. His strip-bodied two-seat 60hp Napier would be accompanied by two other co-driven Napiers – SF’s painted green, the two escorts red and white. Rudge-Whitworth knock-off centre-lock wheels would speed tyre changes, and Napier’s mechanics also used