18 minute read

Locals

Tackling CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT CONUNDRUMS

Even the most experienced educators can run into classroom management conundrums that leave them grasping for answers. In a recent MEA/NEA member survey, 37% of respondents said that managing “repeat offenders” is their biggest classroom management challenge, while 27% struggle the most with keeping students focused. And 17% said that figuring out how to respond to students’ bad behavior is their greatest challenge.

To help teachers get answers, we put members’ classroom management questions to Dr. Allen Mendler, author of “The Resilient Teacher,” “When Teaching Gets Tough,” and “Power Struggles: Successful Techniques for Educators.” Here are his suggestions.

Q: How do you help disruptive students stay on track without taking your whole class off on a tangent? – Sonja B.

A: Let everybody, including disruptive students, know that you’re not always going to stop teaching to handle annoying behavior. And you can also request that the class do their best to ignore that behavior when it occurs. At the same time, you want to reassure them that you will get with whoever has been inappropriate at a time of convenience, and it will be during that private time that you will deal with the student. But unless it’s a serious matter, that time is not going to consume teaching and learning time.

Q: My challenge is with a student who “answers” the question, but really he is using the classroom as a platform from which to perform. (His answers are cleverly disguised as legitimate.) – Diane K.

A: More than likely, the need is for attention. Ask yourself, what are some other more appropriate ways for that student to get the attention he or she is seeking? You might reach out to that student and say, ‘I was thinking maybe tomorrow you might teach a component of the lesson with me.’ Or you might say, ‘You’re answering about 10 times each class, and it’s great that you participate as much as you do, but can you keep it between three and five?’ You’re legitimizing their need for attention, but you’re putting boundaries around it.

Q: How can teachers keep students engaged during times of the year when many students are tempted to mentally “check out,” such as right before the holidays and the end of the school year? – Jossette T.

A: It’s sort of an old-fashioned answer, and that is: Make things interesting. Administer an interest inventory to get an understanding of what your students’ interests are, and then see how you can connect those interests to the curriculum. It’s also important to add some novelty, mix it up a little. If you usually do reading first, then do something else first. Maybe move seats around. Just do some unusual things that are designed to feel different.

Q: How do you keep students off electronic devices during class? My principal has made comments like ‘I’ve seen your classroom in a picture,’ or, ‘A student told me she sent the text message during your class.’ It’s frustrating trying to teach content and do regular classroom management while also having to police electronic devices. – Michelle G.

A: Electronic devices are here to stay. Rather than constantly fighting it, I think it’s increasingly important to build the use of electronic devices into lessons. Prepare lessons that actually encourage use, and let students learn at least some of the content on their electronic devices. Let students know there’s a place to keep their cell phone—it could be on their desk—and that there will be times during class that you’re going to ask them to use it.

Q: Some of my elementary students frequently speak to me in a disrespectful manner, and I’ve noticed that they also speak to their parents this way. How can I establish classroom norms that students will follow if these norms differ from the way they are expected to behave at home? – Diane M.

A: It’s really important to teach what it is that we’re expecting, and not to assume that kids are being willful. I like to say to kids, ‘We don’t talk that way here,’ and then teach them alternatives. For example: “I’m unhappy about that,” “I disagree,” or “I have a different opinion.” Confront the behavior by saying, ‘That sounded disrespectful. Did you mean it to be disrespectful?’ Almost always, they’ll stop, or they’ll just say, ‘Nah.’ Then my response is: ‘Going forward, here is a better way to tell me the same thing.’ If the answer is ‘Yes’—which rarely it is—then we’re going to need to talk about that after class to fix the problem.

Q: It often feels as though my students need to be constantly pushed by adults to stay on task. How can I foster intrinsic motivation? Right now, many of them would rather talk to their friends or play on their phones than complete their class work. – Jennifer R.

A: The best ways of triggering that sense of intrinsic motivation are relevance, success, involvement and enjoyment. Make lessons relevant to students’ lives and set them up for success. I’ll even go to certain kids and say, ‘There are five problems here. Don’t even worry about doing all five. Number two is yours.’ Sometimes I’ll even give kids the answer. I want them to rediscover that they can be successful. The good news is if they’ve learned to be unmotivated, they can relearn to be motivated.

Q: I work with 9th graders that failed the state 8th grade reading exam. Many of them tell me they “hate” to read and refuse to engage with books. How can I help them overcome their previous negative experiences and learn to love—or, at the very least, tolerate—reading this school year? – Elizabeth T.

A: Relate the reading material to their lives. Don’t care so much about what the curricular content is. Care more about how that material relates to their lives. It’s useful to provide hands-on projects that require some reading—not much—and littleby-little, you expand the reading component as the kids’ skills improve. Start small, like with kids eating vegetables: two bites. You might show a movie about a book first. A lot of times, teachers show the movie after reading the book. It’s better to show the movie before the book, because kids at least have an understanding of what the book is going to be about.

Q: How do you get students to follow the rules without help from higher ups? Nothing is done when they get sent to the office. – Frances N.

A: Really, the move of last resort ought to be sending a student out of the room. Too often, people are kicking students out for this, that and the other. Those kids you regularly send out of the room, they’re getting themselves kicked out because they want to be somewhere else. Make it hard for them to be somewhere else. You need to ask, what are those basic needs that are not getting fulfilled. You’ve got to get at those basic needs. Because if you don’t, you’re going to be dealing with those power struggle issues all the time.

What’s Changed in Lesson Planning

BY JACQUI MURRAY NEATODAY.ORG

Technology and the connected world put a fork in the old model of teaching: instructor in front of the class, sage on the stage, students madly taking notes, textbooks opened, homework as worksheets, and tests regurgitating facts.

Did I miss anything?

This model is outdated not because it didn’t work (many statistics show students ranked higher on global testing years ago than they do now), but because the world changed. Our classrooms are more diverse. Students are digital natives, in the habit of learning via technology. The “college or career” students are preparing for isn’t that of their parents.

What is slow to adjust is the venerable lesson plan. When I first wrote these teaching maps, they concentrated on aligning with standards and ticking off required skills. Now, with a clear-eyed focus on where students need to be before graduation, they must build on the habits of mind that allow success not only in school but life.

Here are twelve concepts you may not think about—but should–as you prepare lesson plans:

About a third of high school graduates go to work rather than college so they must be prepared for what they’ll face in the job market. This includes knowing how to speak and listen to a group, how to think independently, and how to solve problems. Lesson plans must reflect those skills.

Students must understand why their project is better delivered with a slideshow than word processing.

Transfer of knowledge is key. What students learn must be applicable to other classes—and life. For example, vocabulary isn’t a list of words to be memorized. It’s knowing how to decode them using affixes, roots, and context.

Collaboration and sharing is treated as a learned skill. Self-help is expected, such as using online references and how-to videos. These are available 24/7, empowering students to work at their own pace, to their own rhythm.

8. Teachers are transparent with all stakeholders. Here, I’m thinking of parents. Let them know what’s going on in class. Welcome their questions and visits. Respond to their varied time constraints and knowledge levels.

9. Failure is a learning tool. Assessments aren’t about finding perfect. In life, failure happens. Those who thrive know how to recover from failure and continue.

10. Problem solving is integral to learning. It’s not a stressful event, rather a life skill. Students attempt a wide variety of solutions before asking for help.

11. Digital citizenship is taught, modeled and enforced in every lesson, every day, and every class. Just as students learned to survive a physical community of strangers, they must do so in a digital neighborhood.

12. Play is the new teaching though it’s been relabeled ‘gamification’. The power of games makes learning fun. I know—this is a lot. Don’t feel like you have to rework every lesson plan immediately. Do a few. Prove to yourself this approach works. Then, spread the word to colleagues that lesson planning has changed.

Jacqui Murray has been teaching K–18 technology for 30 years. She is the editor/author of over a hundred tech ed resources including a K–8 technology curriculum, K–8 keyboard curriculum, and K–8 Digital Citizenship curriculum.

NEED A QUALITY LESSON PLAN QUICKLY? LOOK NO FURTHER!

You can find standards-based plans for all grade levels, along with support materials. Check out these three popular sites:

Share My Lesson: Union-sponsored page has over 300,000 free downloadable resources for educators. Share your own plans and keep up on trends on their blog.

PBS Learning Media: Short videos demonstrate lessons by subject and grade level.

The National Archives: Add archived documents, artifacts, and primary source materials to your lessons.

NEA Lesson Plan Database: Browse by grade and subject for easy to use lessons on a variety of topics and holidays.

What’s Your Elevator Pitch?

Shaping your story and having a good “elevator pitch” about who you are and what you do is vital in communicating with others the importance of your work and the union. But what exactly is an elevator pitch and what makes a good story?

An elevator pitch is something you can share in about thirty seconds to convey your message clearly and effectively. Knowing what your personal and professional story is will help you share your pitch to someone who may be a decision-maker or influencer that could impact your work. Having a good elevator pitch, specific to the importance of the union, is also important when trying to get members to join.

Elements of a Good Story

•A story entertains, enlightens, and educates by making an emotional connection with audience.

•Stories teach us lessons, moral values, and how to make choices.

•Think of some of the stories you’ve known forever…Little Red Riding Hood (Be wary of strangers), Chicken Little (If you’re known to lie, you’ll never be believed)

•If you don’t tell your own story….someone else will! (And you may not like it)

UNION

•Think of an issue you want to talk about. Is it about Opportunity, Student Success, about the Quality Needed in our Schools or about a Reason to Join the Union?

•What story could you tell about this issue?

•Choose an audience.

•How do you want the audience to feel? What do you want people to think, believe, or do (call to action)?

•A story entertains, enlightens, and educates by making an emotional connection with audience.

•Every profession has jargon: shortcut language and insider words/ phrases. Jargon may be convenient, but it sucks the life out of a story!

•What jargon do you and your colleagues use?

•Would someone new to/outside your profession understand it?

•What “real people” words are good replacements for jargon?

Your story or elevator pitch won’t by itself fix every problem or get everyone to understand your issue, but it gets the conversation going. Don’t feel the pressure to cover everything—remember shorter is better. You are the most trusted voices on education; that makes you leaders. You have powerful stories to tell. Don’t be so humble—share them!

Elevator Pitch One Story

I’ve been a teacher for just two years. There is a lot I didn’t know but I was intimidated to ask for help—everyone in my building seemed to know everything and I felt left out. Someone from the local association introduced themselves to me and offered some advice on how to get through the year. I was so grateful to learn there are so many opportunities available to me through my union. I wasn’t a member at the time, but when asked to join, I signed up immediately. After feeling so helpless and lonely, finding a group of people that would have my back made me feel supported and valued. Being a member of the union helps me and my students. I'm a high school science teacher and I've been teaching in the same room, which has carpet, for the last 20 years. I have seasonal allergies. When my classroom flooded and the carpet was removed and replaced with other flooring, my allergies were gone. I realized my classroom was sick. It was making me sick, and it was making my students sick. Other classrooms still have carpet. We need the funding to treat our classrooms and we need legislators to pass legislation with funding to fix this issue.

Reaching “that kid”

Never give up on “that kid.” You can reach them.

You likely all have had or will have “that kid.” So, how you work with that child will affect your day and the education your other students receive. There are some things to remember as you start the day with your students that can help even the most difficult situation.

If you’re asking yourself, ‘What can I do about “that kid”?’ One of the biggest things to remember is nothing that happens with that child is your fault, don’t take his or her behavior personally. Don’t hold a grudge and start fresh every morning. Each day presents a new opportunity.

Always remember, you got into education because you care deeply about your students and understanding how to deal with challenging behavior is part of the job, even for the very best in the business. “That kid” is working through his or her own issues, so relax and heed some advice that’s worked for others.

Jessica Harvey Elm Street School, RSU 16 EA

The first thing when it comes to reaching “difficult students,” above all else, is build relationships. Some students (typically the students who already have their basic needs met at home) are easier to connect with than others. Some students require a bit more effort when it comes to building a relationship and trust. When I meet those students who are perceived as difficult, I sincerely try to empathize with why they may have a difficult time completing their work, following expectations, or participating in socially healthy ways. I ask myself: In what ways are this child’s needs not being met? Exploring this question can sometimes yield direct solutions, but sometimes that question is more difficult to answer. Relationship building might take place through a well-run daily morning meeting, restorative circles, special lunches with students, or distributing positive/kind messages handwritten on sticky-notes.

Students who have experienced trauma or have even a few or a lot of ACEs (adverse childhood experiences) need and deserve a lot of patience. Their brains are taking in a lot of information about the world and are constantly trying to decide whether things are safe or unsafe. When children interpret a situation as unsafe—and this happens regardless of how safe a situation might appear to someone else; i.e. completing a basic academic task, transitioning to a new classroom, a guest speaker visiting their classroom, attending an assembly, etc. [Note: Many examples involve change in routine, which enforces my belief of having clear and consistent schedules that students can see and always access.], their fight or flight system is activated and their logical thinking and reasoning is temporarily disengaged. (I’m thinking of children who are physically explosive during these moments or elope from the classroom.) The number one thing these children need in these moments is to feel and be safe again. This can take some time, but it is necessary before the situation can be discussed with the student (and actions/relationships can be restored, when necessary.)

I’ve worked with and witnessed many students who live challenging lives and therefore may be more challenging to reach in school. With these children, having a strong support system of adults within the school (school counselor, social worker, dean of students, principal, assistant principal, restorative classroom teacher, nurse, secretary, whoever is available, etc.) to support the child and teacher is crucial to their success and mental health. I’ve been in situations where I had virtually no support and felt ineffective and helpless with a student in crisis. I have also been in situations with students where there is an abundance of support at school (and sometimes from caregivers, sometimes not) for the student. Specifically, working with trained and qualified staff in the development of a behavior plan can be motivating and helpful for the student as well as the adults for being able to collect data for analysis while being consistent in response to behaviors.

Another HUGE, imperative, and non-negotiable thing all effective teachers and adults can do to reach these children is to change the way we talk about students who “give us a hard time.” Shifting our thinking and language from them being “students who are giving us a hard time” to students who are having a hard time gives them and ourselves a greater chance to connect and build healthy relationships in our communities. Let’s all remind ourselves: these children are humans who deserve love, support, kindness, encouragement, and sometimes that means they need a second, third, fourth+ chance. It often takes a level of creativity to open a path to learning for some children. It is helpful to take a step back and consider how the children are not the problem, but the systems that uphold societal barriers in our abilities to care for, feed, clothe, house, and access medical and mental health care for our families are the problem. Great teachers are part of the solution.

Calla Jewett Robert V. Connors Elem., Lewiston EA

I tell my kiddos every day that I love them and that they are MY kiddos and will always be, even after they leave my classroom for the last time.

If I hear a song that I think would empower a student, I play that for them. If one of my ELL students says they “love ice cream” and “love Piggie & Elephant”, I add a copy of “Should I Share my Ice Cream?” for my library, say I bought it with them in mind, and that they get to be the first to read it with me. If a kiddo needs socks or food, I go buy it for them. It’s small moments that build strong relationships. They need to know that they matter and that they are loved, no matter how much they push your buttons. We reflect together on hard times in the classroom and make a plan so we can move past them TOGETHER.

Another big piece of advice is when a child is having a hard time, stopping and asking yourself (and sometimes them if your relationship is strong enough) what is TRULY going on that is making them this upset. Usually, it is not the expectation that is placed on them and it is not YOU they are mad at, but some deeper trauma that is surfacing. Taking a moment and remembering that one fact has saved me A LOT of stress and helps me re-evaluate the situation.

Looking for More Advice?

Join the Classroom Management group on NEA’s edCommunities and connect with educators from around the country as they share practical resources and tips for the classroom. Registration is required but the group is free and open to all. Sign up today at mynea360.org

Source: Teaching With Jillian Starr

We’re all the same and all different. This is a lesson that should be embraced, and this is a perfect activity to bring this message home. You can pair up different students throughout the year so they really learn about each other in new ways.

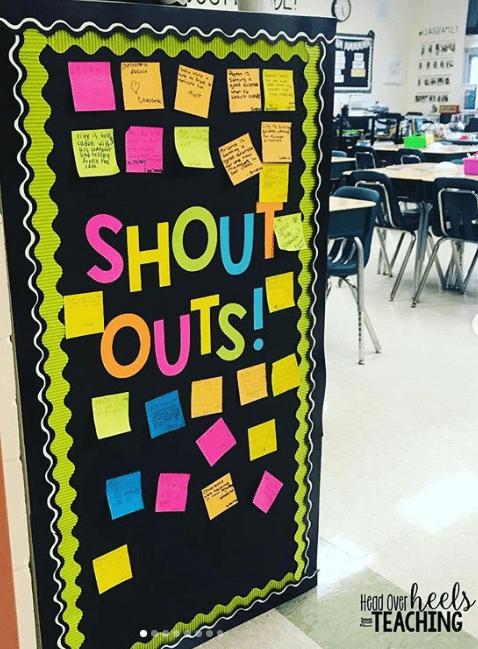

Source: Head Over Heels for Teaching

The classroom door is the perfect canvas. Just grab some Post-it notes to create this awesome community builder. The combo is a perfect way to build student camaraderie throughout the year. September 2019 • www.maineea.org 21