The Fall 2022 Delta Cities Coastal Resilience studio owes a tremendous debt of gratitude to its instructors, Gita Nandan and Lida Aljabar. Their expertise and ongoing guidance was an asset to the entire studio team.

The studio is also incredibly grateful to the Guardians of Flushing Bay team, specifically Executive Director Rebecca Pryor, for their guidance and engagement in the studio process as we developed work that we hope speaks to and supports their vision for the Flushing Waterways.

Alexandre Zarookian

Alyssa Bement

Anna Browne

Dhwani Patel

Harrison Nesbit

Helen Harman

Keshvi Ahir

Maithri Shankar

Molly Blann

Pratap Jayaram

Rita Musello-Kelliher Zein Ahmad Marium Naveed

Intentionally Left Blank

The following report contains research and recommendations developed by students in the Fall 2022 Delta Cities Coastal Resilience studio on behalf of the studio client, Guardians of Flushing Bay. The goal of the studio is to provide technical assistance to Guardians of Flushing Bay in support ecological health and community connectivity with Flushing Bay and Flushing Creek, referred to as the Flushing Waterways.

The first section of this report covers the existing conditions research undertaken by the class as a first step to familiarizing itself with the site. These existing conditions cover the history of the area, land use and zoning, current waterway accessibility, public health, sensory conditions, impermeability and flood vulnerability, and an edge conditions analysis. The existing conditions research was greatly enhanced by students’ opportunities to engage directly with the community through Guardians of Flushing Bay’s engagement event Day at the Bay and various working tours with local experts.

The recommendations reported in the next section of this report are based on the existing conditions research conducted by the class, and are organized into three sections by topic: policy and planning, environmental and placemaking systems, and education and community engagement. Within each of these topics are recommendations dealing with the rights of nature, long-term funding strategies for resiliency efforts and ways to address land use in a more resilient manner, engaging with local industry to advance ecological health, remediating combined sewer outflow (CSO) pollution, community engagement through outreach and citizen science, and a democratic way of sharing data on the site.

At the end of this semester, the Delta Cities Coastal Resilience studio had the opportunity to present its work to Guardians of Flushing Bay and its community partners at Flushing Town Hall. This event is discussed last, in conjunction with a brief conclusion and suggestions for future directions.

The Delta Cities Coastal Resilience (DCCR) Studio emerged in 2015 following the Recover, Adapt, Mitigate, and Plan (RAMP) program and related studios at the Pratt Institute’s Graduate Center for Planning and the Environment. Now completing its seventh year, the DCCR studio aims to address the vulnerabilities unique to delta cities in the face of climate change. The studio places specific emphasis on the built environment conditions of a given site in exploring potential interventions and planning strategies. However, the studio also encourages a radical reconsideration of how delta cities are planned, and a reimagination of how such planning might take place in the future.

This semester’s DCCR studio was taught by Professors Gita Nandan and Lida Aljabar in the Sustainable Environmental Systems graduate program within the Pratt Institute Graduate Center for Planning and the Environment. The students in this course were Keshvi Ahir, Zein Ali Ahmad, Alyssa Bement, Molly Blann, Anna Browne, Alexandre Zarookian, Dhwani Patel, Harrison Nesbit, Maithri Shankar, Marium Naveed, Pratap Jayaram, Rita Musello-Kelliher, and Helen Harman.

The client for this semester’s studio was Guardians of Flushing Bay in Queens, New York.

Guardians of Flushing Bay is a coalition of human-powered boaters, park users, and local residents advocating for a healthy and equitably accessible Flushing Waterways. We accomplish our goals through family-friendly waterfront programming, community science and stewardship, and grassroots organizing. - Guardians of Flushing Bay Mission Statement

The first step in this studio process was conducting thorough existing conditions research on the land surrounding Flushing Bay and Creek, as well as on the waterways themselves. This research was greatly enriched by opportunities to speak with stakeholders at community engagement days such as Day at the Bay and walking tours with local artists and experts. The students then developed their knowledge of the site into recommendations that target specific topics and challenges that Guardians of Flushing Bay sought to address. It is the hope of this course that these recommendations can serve as the starting point for further conversation and coalition building among the true experts, Guardians of Flushing Bay and the community it serves.

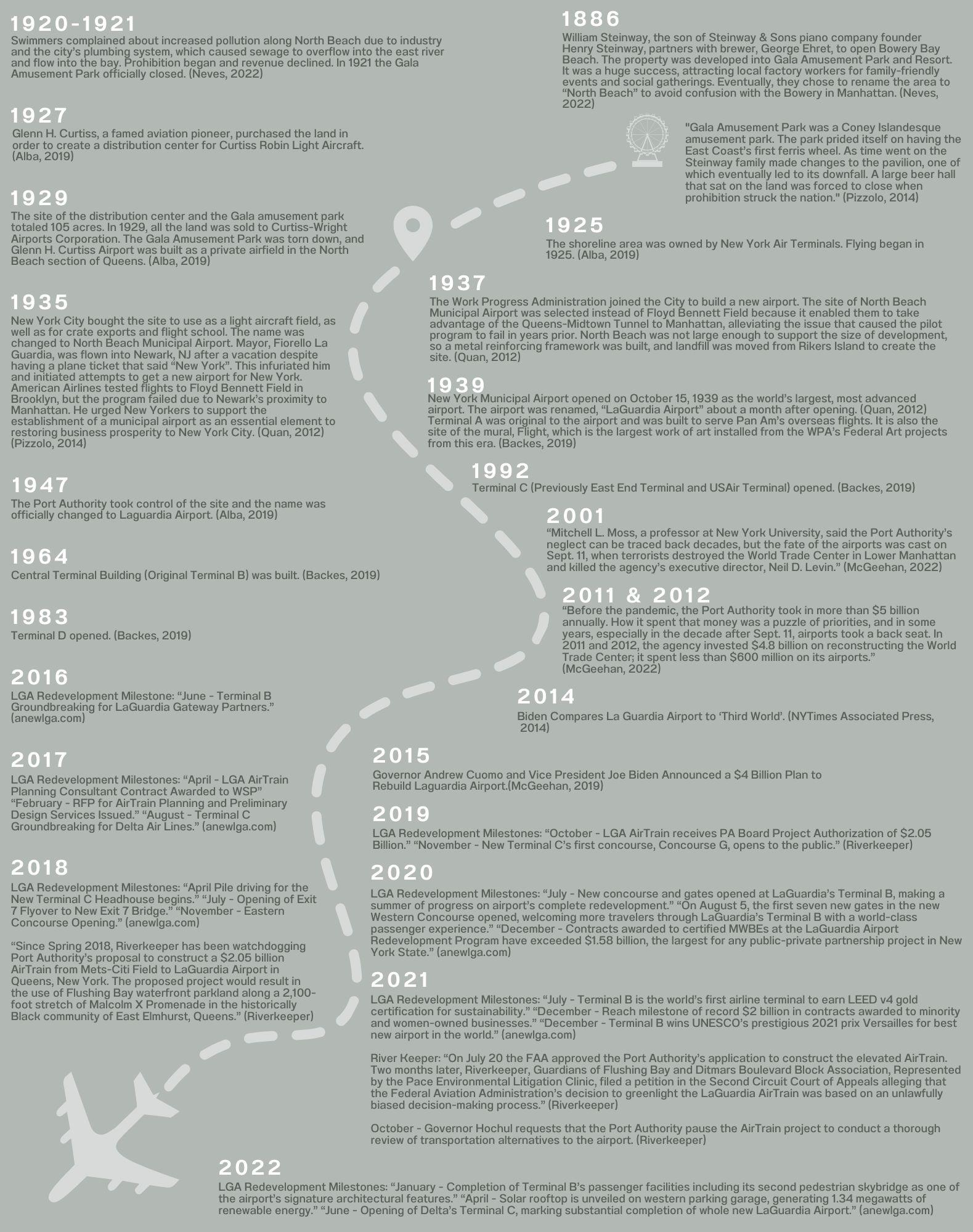

To contextualize the conditions of the creek and surrounding community today, we had to understand the history of the site. This historic marshland first became threatened when European colonizers violently displaced the Matinecock Indians and began building permanent settlements along the river and bay. Following English occupation of the area, it was settled by Quakers, whose tolerant views invited the growth of a sizable free Black population.

During the late 19th century, the creek became a notable recreational area for boaters and enthusiasts, but industrial uses came to dominate the waterfront in the early 20th century. Made famous by the “Valley of Ashes” moniker coined in The Great Gatsby, the west side of the creek became a dumping ground for garbage and industrial waste, generated by the coal and construction material facilities that sprung up along the water. Notably, while many industrial facilities still exist along the waterfront today, manufacturing is not one of the top five industries of employment for either residents or workers.

In the 1930s, dramatic changes would come to the area around Flushing Creek. In 1938, the Home Owners Loan Corporation redlined all of the neighborhoods adjacent to the creek, assigning them a D grade. Additionally, the west side of Flushing Creek was identified as the site of the 1939 World’s Fair, and in a process led by Robert Moses, the area was cleared of garbage and developed into the park that it remains today. This would be the first of two World’s Fairs hosted in Flushing Meadows Corona Park, the second occurring in 1964. Moses was not done changing the neighborhood, as in 1950 he masterminded a plan to demolish 49 dwellings in Flushing to build a 1,100 car parking lot and the NYCHA Bland Houses, displacing 250 families and 38 businesses.

The removal of national immigration quotas in 1965 led to a huge of immigration from East Asia into Flushing. While in 1960 only 0.88% of residents identified as a race other than “White” or “Black,” in 2020, 51.38% of residents identified as Non-Hispanic Asian.

The past decade has been juxtaposed between the growth of private real estate interests, and the fight for environmental justice in Flushing. In 2018, Willets Point was designated a Brownfield Opportunity Area, paving the way for both rehabilitation and private investment. In 2020 the massive Special Flushing Waterfront District plan was unethically approved, rezoning 29 acres of the waterfront for luxury housing. And finally, in November 2022, the city announced a plan to redevelop Willets Point, centered around a soccer stadium for New York City FC.

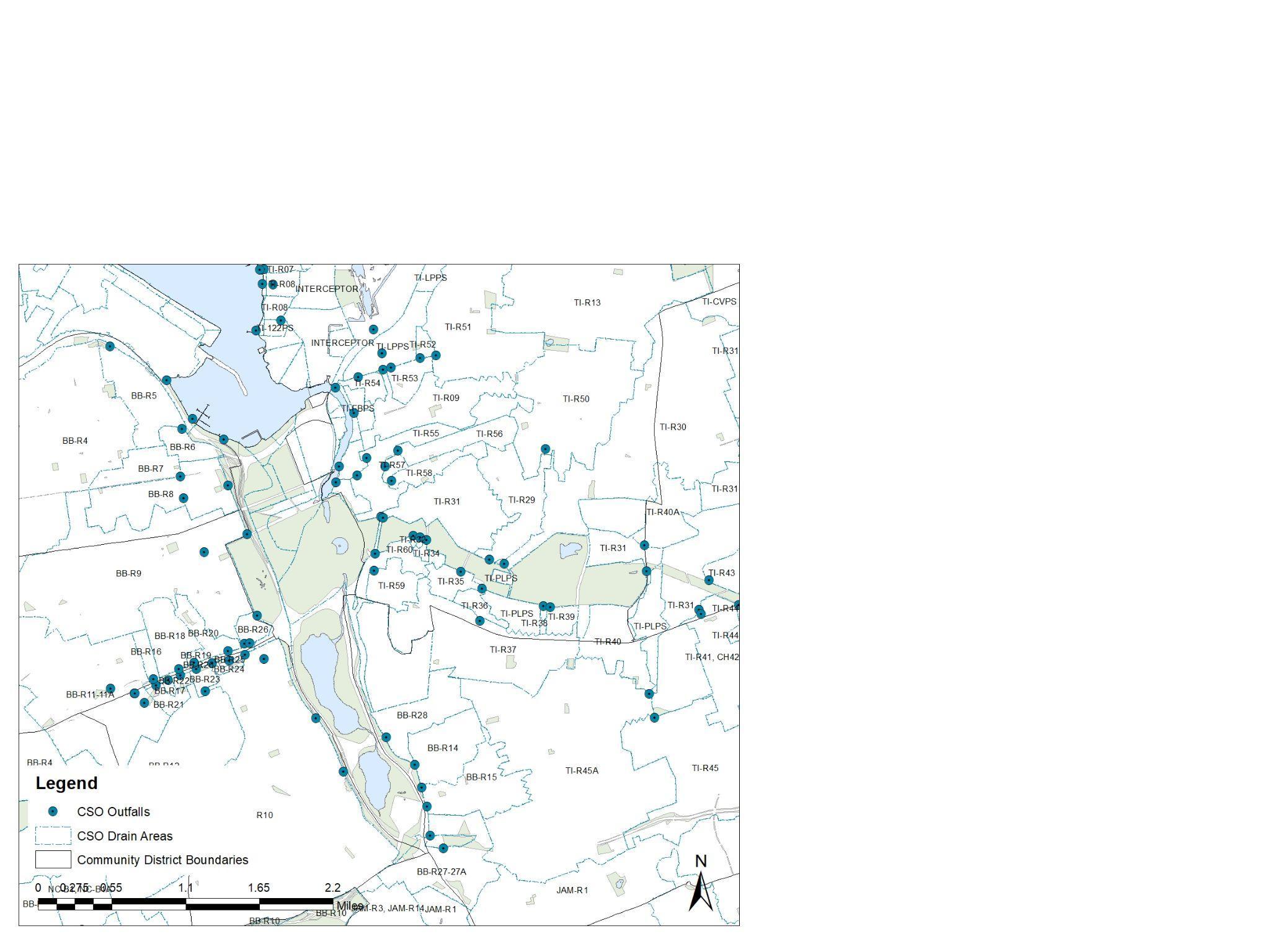

All of this development has created a concerning lack of open and green space. In the study area, there is less than 1 acre of open space per 1000 people. In addition, large areas that are considered “green space” are impermeable spaces like parking lots, leading to stormwater management issues. These issues are compounded by the presence of 5 Combined Sewer Outflows (CSOs) within a 2 mile distance of each other, all along the creek and south end of Flushing Bay.

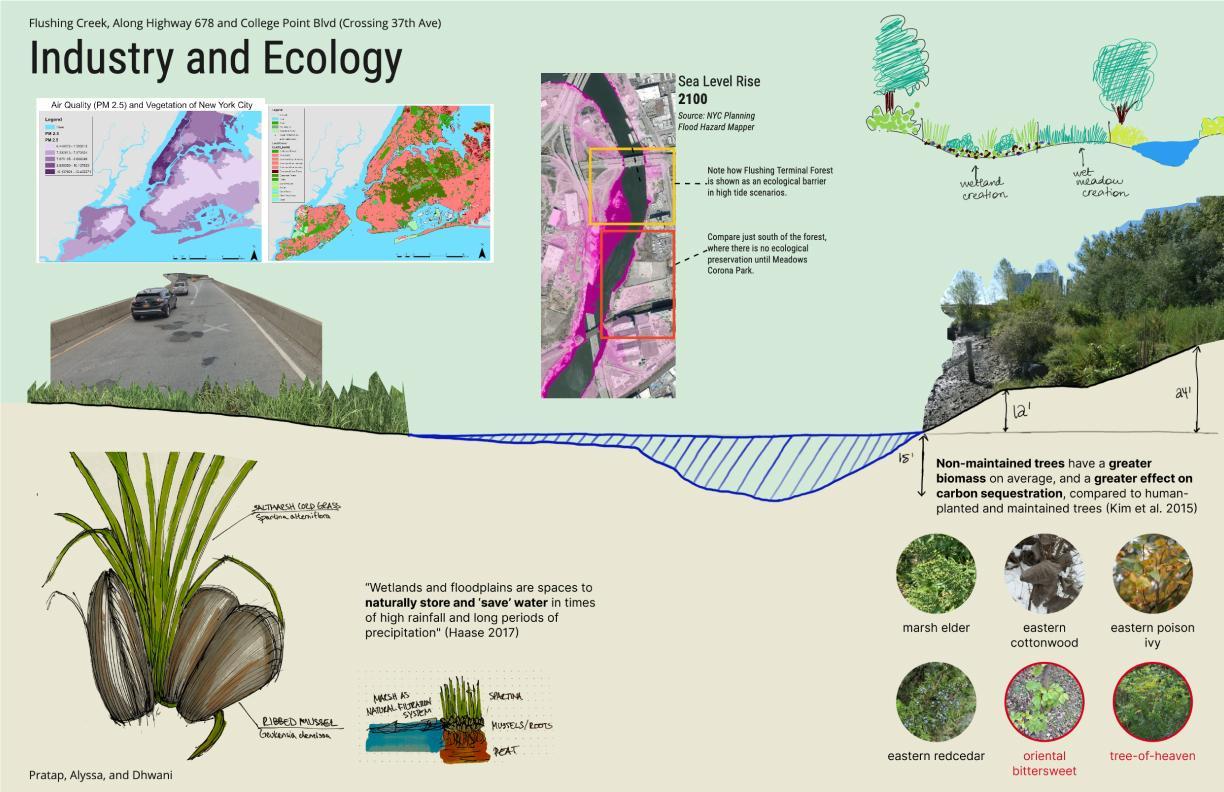

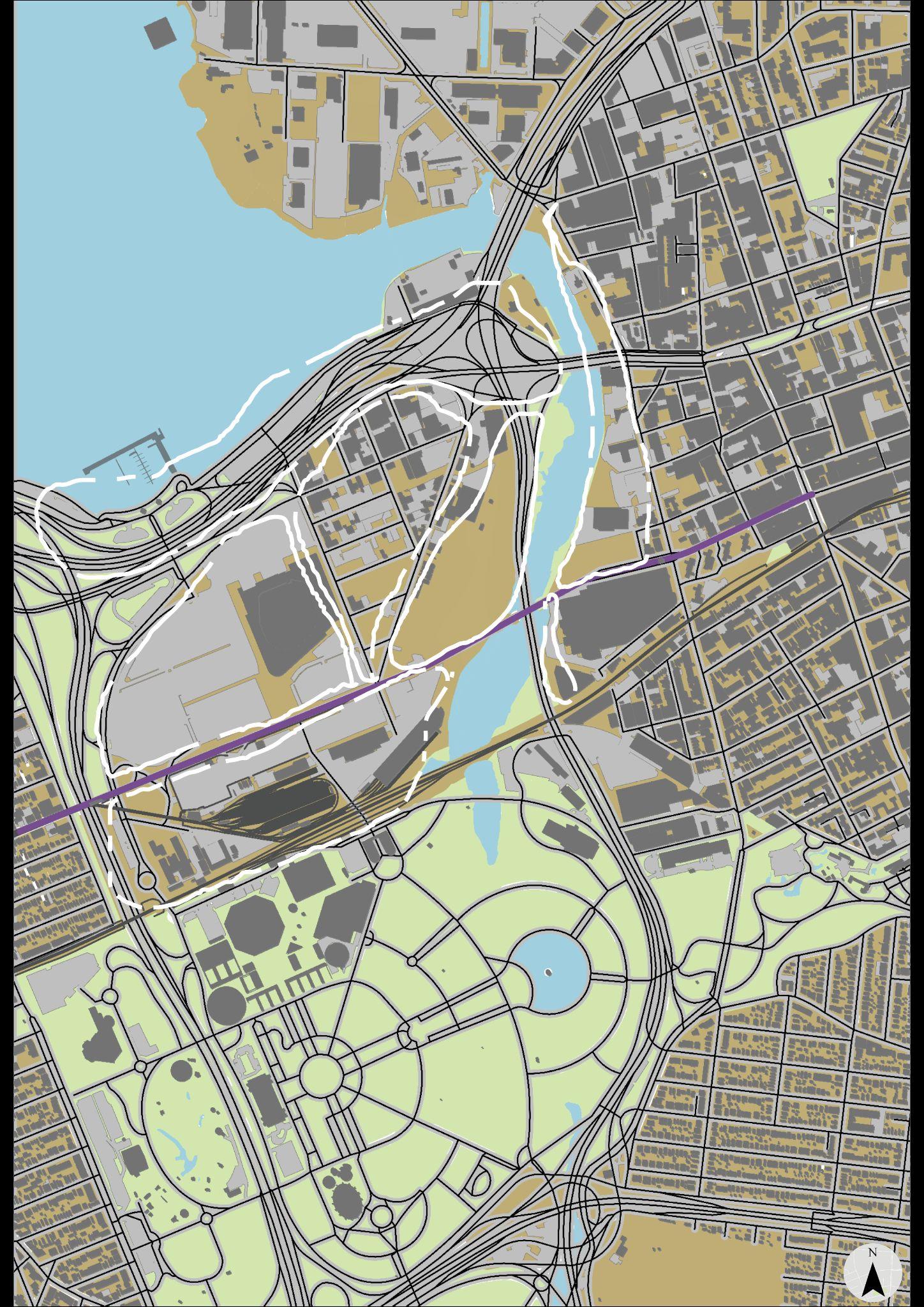

For the transect analysis, we worked along Highway 678 and College Point Blvd, crossing 37th Ave. Our focus was on the relationship between industry and ecology in the study area. The right side of the transect included Flushing Terminal Forest, a 30-year natural ecosystem adjacent to the U-Haul site. The forest was contained with native species including marsh elder, eastern cottonwood, eastern redcedar, and eastern poison ivy. Due to maintenance neglect, there are also oriental bittersweet and tree-of-heaven species overgrown in the parcel, both of which are invasive. Nonetheless, with low amount of green space in the study area, the undeveloped forest is a strong component of both decreased flood risk and better air quality for Flushing.

The left side of the transect includes a piece of the wetland, where ribbed mussels and spartina provide water filtration and flood mitigation services to the landscape. The road directly above the marshland, Highway 678, affects the ecosystem services the natural environment can provide. Through this work, we conclude that in this study area, preservation is needed for land like the Flushing Terminal Forest, and the natural wetland framework currently existing should be expanded on in restoration projects.

Land use along the creek is primarily a mix of industrial & manufacturing, vacant land, and parking facilities. There are a few commercial & office lots set just off the creek, and it’s worth noting that the entire promenade on the Bay is shown as Transportation & Utility but is actually the promenade and that parking lot.

Most of the zoning along the creek is commercial and manufacturing, including three special districts shown here: Special College Point District, which is primarily focused on maintaining manufacturing land uses and the business park; Special Willets Point District, which is slated for redevelopment into a mixed use site focused on entertainment and retail; and Special Flushing Waterfront District, which is also planned to be a mixed use site with a hotel and plans for connecting downtown Flushing to the creek with public esplanades.

Most of the lots along the east side of the creek are listed by PLUTO as unknown, which usually means they are privately owned. However, the rest of the creekside lots are either fully tax-exempt or City owned.

Existing conditions were documented for each of the four reach areas outlined in the Flushing Waterways 2018 Vision Plan. The collage illustrates the variety of waterway access types, uses, and challenges that impact stakeholders’ opportunities to interact with the waterway today. Access is impacted by several factors, including, zoning, land use, combined-sewer overflows, physical barriers, and lack of connectivity and wayfinding.

REACH #1 - LAGUARDIA WATERFRONT

“Inaccessible by Design”: This area is bounded by LGA, a rocky break wall, and the western end of the promenade. It also has largely polluted tidal marshes and mudflats. Daily airport operation alters the landscape and environment and limits opportunities for safe access.

REACH #2 - COLLEGE POINT “Informal Public Access”: An inlet provides informal access to the Bay via a bordering parking lot. The inlet is otherwise bordered by College Point Boulevard & an industrial site.

REACH #3 - BAY PROMENADE “Formal Public Access” / historic site of connectivity and access: Flushing Meadows/Corona Park Kayak Canoe Launch provides public access to Flushing Bay for fishing, boating, and jet skis, which are technically prohibited.

REACH #4 - CREEK “Varied Access”: The Creek supports water dependent industries as well as established forest and wildlife habitat, but public access is severely limited. CSO’s increase pollutants. Wetlands are in varying condition, and major highways and transit infrastructure create difficult-to-navigate and impermeable boundaries between the creek and surrounding community.

This analysis uses public health as a lens with which to understand existing conditions within Flushing Creek. Our findings were initially divided into three organizing categories: land, air, and water. These help to frame the conditions which impact the health and wellbeing of Flushing residents living nearby the Creek, those who visit it, and the flora and fauna that inhabit this space, too. This study reveals a spectrum of public health issues, including air and water pollution, a dearth of bike lanes and unsafe sidewalks, all of which will be amplified by climate change. In weaving climate change considerations into public health themes, we see how interconnected these topics are.

Solutions to one are likely to benefit the other. This concept is outlined in two Systems Thinking diagrams addressing the co-benefits of addressing climate change in Willets Points and improving access to green spaces near urban waterfronts. While a myriad of public health concerns impact Flushing Creek may seem distinct or unrelated, they must not be seen or researched in silos. The effects of climate change cannot be considered in isolation. Issues already plaguing the public health sector will be amplified by climate change.

By 2080:

● Precipitation in NYC is expected to increase by five to thirteen percent due to climate change, which will increase the amount of combined sewage overflow (CSO) and increase breeding areas for mosquitos (NYC DEP, 2022).

● Temperatures will rise between five and nine percent and have triple the amount of heat waves from a 2000-2004 baseline (NYC DEP, 2022). Higher temperatures lower air quality and can cause a variety of heat-related illnesses, particularly among the City’s most vulnerable residents (US EPA, 2022).

● Sea levels are expected to rise in Flushing between thirteen to fifty-eight inches

This not only affects the community economically because of property damage, but will increase stress on Flushing’s residents due to displacement fears (US EPA).

Moreover, these issues disproportionately affect underserved communities and BIPOC communities. For example, Asian-Americans are exposed to twice as much PM2.5 as white residents and Latinx residents breathe as much as 82 percent more vehicle pollutants than white Americans (Union of Concerned Scientists, 2019). This is significant considering Flushing has the largest Chinese population in the City as well as the most immigrants citywide (NYS Comptroller, 2021).

Vector-borne diseases are a distressing yet helpful indicator of the relationship between the public health sector and the climate crisis. The first documented case of West Nile Virus (WNV) was found in 1999 in Northern Queens, near Flushing (Meko, 2022). Since then, Queens has routinely had the highest number of mosquito larvae found in static pools of water citywide (Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2022). Increased precipitation and higher average temperatures have already seen a rise in mosquito populations with WNV citywide, and this trend is expected to continue (Meko, 2022). A compounding effect from this is the NYC’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene's “Comprehensive Mosquito Surveillance and Control Plan”, which relies on aerial larviciding and adulticide spraying (from trucks) during summer months in areas with higher mosquito populations (NYCDOH, 2022). North queens are routinely sprayed with these toxins which may contribute to air pollution or be a deleterious effect on the Creek’s fragile ecology.

A transect diagram offers an accessible, distinct vantage into understanding a set of issues. To highlight various pollution sources, both quotidian and legacy pollutants, along the Creek, we cut a transect looking southward toward Flushing Bridge along College Point Boulevard. From this perspective we documented a wealth of pollutants including,

● Nonpoint source pollution from concrete manufacturers on the eastern side of the Creek.

● Heavy-duty vehicle pollution along the east and west sides of the Creek, as well as those traversing the Flushing Bridge.

● Bulk chemical storage facilities within the 500-year floodplain on the west side of the Creek.

● Lack of bike lanes along the bridge and the west side of the Creek, which also lacks any pedestrian walkways.

● Legacy pollutants including PCBs, petroleum spills, VOCs, and heavy metals (Dept. City Planning, 2020).

Flushing Creek is situated in the flightpath for LaGuardia Airport and sits at a highway interchange. The affecting flightpath for LaGuardia was originally implemented to divert air traffic noise away from the U.S. Open, but since 2012 become the permanent flightpath year-round (Khafagy, 2020). These major transportation factors contribute to the environmental noise impacting the area. Environmental noise due to transportation, development, and urbanization impacts human health and the health of wildlife (Shannon et al., 2016). Noise pollution presents threats to the health and quality of life of these populations. Environmental effects of sound can be broken down into four characteristics: pressure level or perceived loudness (decibels); frequency, or the rate at which sound vibrates, perceived as the ‘pitch’; duration, for example a sound that is recurring, continuous, or intermittent; and tone (Sama, 2001).

The map shows the road, rail, and aviation noise potential in and around Flushing Creek. This is potential noise exposure, and through our research we found that accurate, up to date measures of noise pollution-while felt by community members-is a gap in available data about the area. To this end, we documented noise as experienced during our site visits, as shown in the line drawing and call-out box in the image.

Noise pollution, like air pollution, has significant impacts on human health. Excessive environmental noise can contribute to auditory and non-auditory negative health outcomes from annoyance and sleep difficulties to dysregulation, hypertension, cardiovascular impacts, and impacts on mental health (Casey et al., 2017; Ramphal et al., 2022).

Noise pollution also has significant impacts on wildlife and can alter the ecology in a region (Francis et al., 2012). Noise can reduce habitat quality, chronic noise can degrade communication and orientation, and industrial noise can alter movement patterns of marine mammals and impact the physiology of aquatic species (Shannon et al., 2016).

Border Vacuums, a term coined by Jane Jacobs, are possibly one of the most disruptive and influential urban anomalies that appear in our cities. She states:“a border - the perimeter of a single massive or stretched out use of territory- forms the edge of an area of ‘ordinary’ city. Often borders are thought of as passive objects, or matter-of-factly just as edges. However a border exerts an active influence.” These Border Vacuums pose a challenge in providing equitable access to the waterfront at Flushing Creek. Flushing by itself is a thriving neighborhood, with many neighborhood assets, diversity being at its forefront. The creek and its immediate vicinity does not have clear access, neither visually nor physically. Chronic disinvestment in the areas around the creek has also resulted in apprehension by the public from approaching it.

How can quality of life of Flushing Creek and the residents improve through an understanding of Social and Environmental Sustainability?

Development and growth that is compatible with harmonious evolution of civil society, fostering an environment conducive to the compatible cohabitation of culturally and socially diverse groups while at the same time encouraging social integration, with improvements in the quality of life for all segments of the population is what can be considered social sustainability. It occurs on an everyday basis, and brings community trust.

What are the intersections between flood risk and vulnerability?

When creating climate change mitigation or adaptation interventions in the area around Flushing Creek, there must be consideration of who and what is most vulnerable to flooding. This map therefore explores vulnerability in and around the 500-year floodplain, defined as an area where there is 0.2% chance of flooding in any given year. We calculated the number of buildings and housing units within these flood zones, along with the area (sf) of various land uses.

All flood zones in the 500-year floodplain are shown. This floodplain is for the 2050s and is based on both FEMA’s Preliminary Work Map data and the New York Panel on Climate Change’s 90th Percentile Projects for Sea-Level Rise (31 inches).Residential buildings with basements below grade are drawn.Sources: NYC Open Data, NYC mapPLUTO, Esri, HERE, Garmin, GeoTechnologies, Inc., USGS, EPA, USDA, Census

Age, income, and housing are a selection of factors that influence the experience of flood exposure. Our map thus identifies the location of residential buildings with basements below grade, daycare centers, nursing homes, and public housing. Relevant resilience projects and plans have also been added to provide context on existing and future work that will impact this study area.

How can we ensure mobility of Flushing residents in both everyday and extreme cases?

Transit zones are densely populated areas with low rates of car ownership and high rates of affordable and senior housing. While these zones are located near public transportation, extreme weather events—including heavy precipitation—have proven to challenge our transit infrastructure.

For the transect study, the stretch of Roosevelt Avenue connecting the Mets Willets Point Subway and Main St. was considered. The 7 is the only local subway train serving the neighborhood. We focused on the following factors:

How can we bring people to the creek in a way that benefits the creek and the people who live there?

Flushing is a thriving neighborhood, with some of the most culturally diverse people and places. Flushing Bay brings many people during major cultural events like the dragon boating festival. How can the creek also act as an anchor in the neighborhood, to bring about better social relationships and bring about stewardship among the residents to better improve the physical well being as well as quality of life in Flushing?

The edge condition analysis started with inquiring the about the past, present and future of the U-Haul site. Photos on the right display a bucolic scene (top) from the 1800s when the area surrounding the creek was farm and marshland. Today this edge has been hardened with bulkheads to support operational functions of the U-Haul building and to assist with their barge mobility. A rendering done by MAS NYC shows the future of the site where tall buildings restrict access and sightlines to the creek for the Flushing community. The stark differences in these three images and understanding their impact on the community’s relationship with the creek is the motivation for continuing to map different typologies of edges present all along the creek (detailed on the next page).

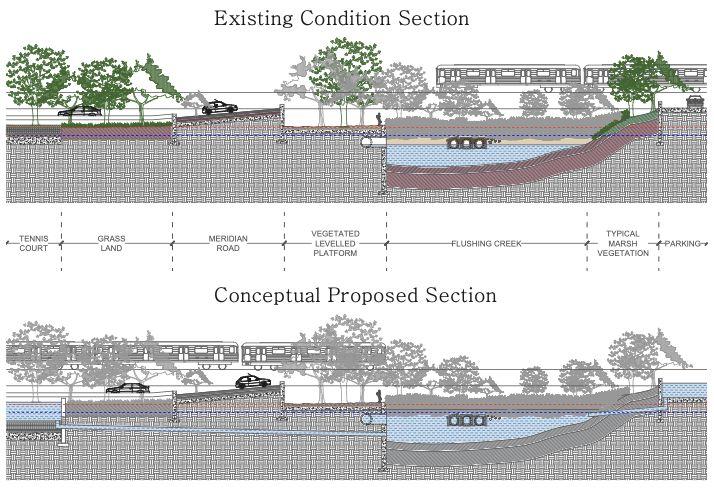

Another aspect of edge condition mapping was seeing the transect of the creek to better understand its composition and function. The transect below has been taken at the tip of the creek where it enters Flushing Meadows Corona Park.

How does the edge condition narrate a story of the Flushing Creek?

The Flushing Creek has worked as an effective system of water management and water containment for hundreds of years. Originally fed by three adjacent creeks and carrying their water into the Flushing Bay, the Creek has changed significantly in its form and purpose over the years. The most significant change was during the World’s Fair in the 1900s. This was when more than half of the creek was piped underground the newly constructed Flushing Meadows Corona Park and the remaining waters fell prey to neglect and decay.

The edge condition study is an attempt to understand the creek as a system of natural and manmade elements and viewing the creek in its entirety, starting from the Whitestone Expy and ending in the two lakes in FMCPark. The conceptual sections accompanying the edge conditions map, this speculation elaborates the elements and the material that the water interacts with: bulkheads, vegetation, riprap, toxins and trash, pipelines, floodgates. All of these elements play a role in maintaining the health of the creek system, which includes water and the flora and fauna it is a habitat too.

On September 24, we spoke with attendees of Guardians’ Saturday at the Bay, where we heard about their desire for the waterfront to transform from an inaccessible and polluted space to an inviting recreational space for local residents, young and old.

To engage with the community members at the event, we conducted a pop-up version of the Place It! workshop, created by James Rojas and John Kamp. In this workshop, participants interact with a visualization of a space (in our case, a large printed map of Flushing Creek, Flushing Bay, and the surrounding neighborhoods) and use found objects and improvised crafting materials to construct an ideal vision of this space. The scenes that they craft are then an opportunity to engage participants on the values and beliefs they hold about the space. Our station was particularly effective at drawing in young people, which allowed us to converse with their parents about the Flushing waterfront. The set-up welcomed visitors and we were able to have a few in-depth conversations with people about specific areas on the waterfront.

Documentation of the existing conditions throughout the Flushing Waterways and surrounding communities was essential to determining the primary goals for our recommendations and next steps. Through observations and analyses, we defined the following key takeaways:

1. The health of the creek and the health of the community are intricately intertwined, and dependent upon each other. Community stewardship of the creek must be prioritized for future generations.

2. Flushing Creek and Bay support a vibrant ecosystem and serve as an abundant resource to the region. Policies should protect the rights of the waterways.

3. Access is extremely limited and difficult to navigate, which inhibits the community’s ability to enjoy this abundant resource, and in turn limits the degree to which the community feels connected to the waterway.

4. Existing land uses fall short of the overall potential for the local area and the region, and in some cases, are negatively impacting the creek and the surrounding communities.

5. While the creek supports some water-dependent industry, opportunities exist to create a resilient shoreline and a symbiotic relationship between the waterway and the economy.

6. Existing edge conditions and impermeability create vulnerable conditions and increase flood risk. Stormwater management infrastructure is critical to creating an equitable future for the waterway and surrounding communities.

The chart below includes our initial summary of themes and prospective goals that were considered in forming recommendations. These were further refined and adapted through research and precedent analyses. The resulting recommendations were synthesized into eight proposals, which are described and illustrated in the following section.

Policy Protect the future health of the creek and the community through a commitment to new policies and rights of nature.

Community Stewardship Plan for sustained community engagement in order achieve successful stewardship of the creek over time.

Advocacy, Education, Communication Facilitate advocacy efforts of GoFB and Partners through an archive of tools, such as data sets, maps, and engagement methods, that are easy to incorporate into campaigns and programs.

Cultivate a bond between the waterway and the community through a field station.

Programming: Education, On-site Infrastructure, Workforce Development

Invest in infrastructure, workforce development, and ecological restoration that generates a hub for resilient shoreline design.

Cultivate a bond between the waterway and the community by increasing access to the waterway and allowing it to be used to its full potential through placemaking and wayfinding.

Create a new set of standards for future development, focused on multi-generational, affordable land uses.

Create a structure that upholds a cohesive vision for the waterfront community including, design, management, maintenance, funding, and climate vulnerability projections.

Revelop surrounding areas to function as stormwater management infrastructure.

Generations of people have benefited from the abundance offered by Flushing Creek and Bay. However, the state of these waterways today reflects decades of neglect and exploitation. We present a reparative vision and offer a roadmap for centering the health of Flushing Creek and its collective ecology through community action and involvement. The vision presented through this exhibition illustrates a symbiotic relationship between community and creek that leads towards a self-sustaining ecosystem for generations to come.

We foresee this vision of the waterfront through eight specialized recommendations, drawing from the following disciplines: ○ Policy and Planning ○ Environmental and Placemaking Systems ○ Education and Community Engagement.

These recommendations use an interdisciplinary approach, while working with one another to create a holistic vision for 2100.

This section outlines policies and frameworks that address a range of issues from legal-rights for nature, novel funding strategies, and establishing a community land trust.

Project 01: Flushing Creek Rights of Nature Project 02: Flushing Resilient Improvement District Project 03: Flushing Waterways Community Land Trust

In 2100, Flushing Creek will have legal personhood and a devoted Council of Protectors to protect the creek and its ecology against harms caused by development and urbanization. Guardians of Flushing Bay (GoFB) will play a major role in achieving this protection and in bridging the gap between community and creek. To engage people with the concerns of the Creek, people must engage with the Creek itself. This vision for the future is based on Rights of Nature movements and relies on participatory community action to achieve a just and healthy creek ecology.

Rights of Nature movements around the world recognize and demand the need for natural ecosystems to be treated as entities with inalienable rights to exist and flourish. The movement challenges the modern, colonial understanding of nature, especially rivers and forests, as commodities that can be bought and sold, and establishes them as a relative and an intrinsic member of the community. The foundation of the movement is based on indigenous beliefs and customary law and it is, in most places, led by indigenous communities. The aim of a Rights of Nature movement is to take guidance and precedence from traditional stewards of nature rather than rely on top-down action in the form of environmental policies.

The movement is led by indigenous leaders who have a generational, close-knit, and interdependent relationship with the region’s rivers. Many resident communities and nature groups are working to address the historic harms and continued threats to the river ecosystem by building people’s connection with the rivers and by securing legal and ecological protection for the river.

An essential tenet of Rights of Nature movements is the bottom-up, participatory approach they have in bringing about a framework shift in environmental policy.

This project recognizes that the process and quality of engagement is just as important as engagement itself. Participatory action research for this project envisions research and development of plans for the Rights of the Creek through participatory action with people directly in the Flushing Creek community. The method believes in the expertise of experience of these groups to co-create a bottom-up planning process.

Flushing waterways are home to diverse animal and plant species. The creek is also impacted daily by discharge of untreated sewage from CSOs, creating an unfit habitat for wildlife or human contact. Dredging and increased imperviousness for waterfront development makes the creek incapable of expanding. Tidal gates, both existing and proposed by the USACE HATS study, disrupt the flow of water and migratory patterns of fish. These structural and elemental changes to the creek have deleterious impacts on the health and character of the creek.

The Rights of Creek movement proposes a framework shift to reposition the Creek not as a resource but as an intrinsic member of the Flushing community with legal rights. Envisioning the Rights of the Creek movement takes GoFB’s advocacy work further to demand legal protection for the creek. The Rights of the Creek movement emphasizes the interconnected and cyclical relationship between creek and community. It is critical that the perspective shift is guided by participatory action of the community as they become guardians and protectors of the Rights of the Creek.

A Path to Action: The Rights of Creek movement can be spearheaded by GoFB and the Flushing community through the following actions:

1. Establish a Council of Protectors: Build coalition and support for the Rights of the Creek movement with the local community, including leaders and members from Flushing’s Matinecock Indian tribe, environmental artists, scientists, and lawyers, as well as local institutions. The initial coalition forms the first iteration of the Council of Protectors, identifies the elements for the Bill of Rights for the Rights of the Creek, and sets the foundation and direction of the movement.

2. Community Action: The Council of Protectors advocates for the Rights of the Creek and builds people’s connection with the creek through community actions. These actions serve a dual purpose of fostering community knowledge and connection and serving as the ground level planning work for the bottom-up approach of the movement.

● Expand citizen science efforts to be multisensory to fill in gaps in knowledge

● Hold co-learning workshops to build awareness and connection between creek and community

● Host creative workshops using storytelling and artistic actions to process grief, celebration, and inquiry around the Rights of the Creek movement and knowledge and concerns generated by the community.

Image caption: A systems diagram illustrating the perspective shift proposed by Rights of Nature: from seeing the creek as a resource to highlighting the cyclical relationship between creek and community.

3.

of

: Gradually expand to ensure a community-led approach. The expanded coalition aims to include city, state, and federal entities involved in environmental protection. With these connections and community action in place, the movement can pursue legal action.

4.

The Council of Protectors advocates for the formation of an advisory subcommittee to the New York City Council Committee on Environmental Protection that has jurisdiction over Rights of Nature movements. Rights of Creek acts as a pilot initiative and movement in NYC to inspire other groups to take action within their communities. The subcommittee functions as an aid to the movements, simplifying and expediting the legislative process.

The Environmental Rights Amendment passed in New York (2021) is an addition to the Bill of Rights of the New York State Constitution stating, “Each person shall have a right to clean air and water, and a healthful environment.” The Rights of Creek movement can make a case and object to these rights being denied and violated because of the quality of water collected through citizen science programming in the Flushing Creek and Bay.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Article 25 states “Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain and strengthen their distinctive spiritual relationship with their traditionally owned or otherwise occupied and used lands, territories, waters and coastal seas and other resources and to uphold their responsibilities to future generations in this regard.”

Identifying and acting on connections between the Rights of Creek movement and the existing legal and environmental armature can give leverage and teeth to the movement.

5.

Armature: While the Rights of Nature movements are focused particularly on preserving and demanding rights for natural ecosystems, it can be helpful to frame the project concern within the context of its impact on human populations. It is important to make a distinction between ‘rights of nature’ and ‘rights to nature’, in which the latter refers to humans’ right to access clean and healthy natural ecosystems. The harm caused to water in Flushing affects not only the resident community but the ecological community on a much larger scale. CSOs and other toxins in the Flushing waterways travel up to the waters of Long Island and Connecticut which are occupied by indigenous tribes and communities.

A bill of rights for the Creek radically shifts the perspective and positions the Creek as a central figure in the Flushing community. Once the creek has legal protection, it becomes a mandate, rather than a set of guidelines, to put the interest and health of the creek at the foremost. The Council of Protectors holds legitimate authority to challenge and inhibit any development that encroaches upon the rights of the creek. This form of protection ensures that the creek and its ecology is able to exist, flourish, and regenerate.

The stewardship and participatory action in achieving Rights of the Creek applies community-led planning actions to the urgent needs of the Creek and its ecosystem, and serves as a model for community-led resilience planning.

There is an influx of new residential and commercial development along and near the Flushing Waterways, creating a need to ensure that these changes meet the needs of the existing community, and are adaptable to conditions of sea level ride and climate change. A combined strategy that reinterprets New York City’s Business Improvement District (BID) model and incorporates an Environmentally Sensitive Maritime Industrial Area designation can support funding for resilience interventions and support environmental remediation in the area surrounding the Flushing Waterways.

The Flushing Resilience Improvement District (FRID) is a long-term funding strategy based loosely on New York City’s Business Improvement District model. The FRID would focus on Flushing Bay and Flushing Creek, ensuring an equitable distribution of funds. Critically, the FRID differs from a traditional BID in its resilience and waterfront focus. Attention must be paid to categories of assessment, that is, how much different land owners will be asked to pay in order to support those objectives. The FRID would address limitations and challenges arising from special regulations and waterfront area zoning requirements.

Implementing the FRID would require an application in accordance with the official BID procedures of NYC Small Business Services. This process requires significant buy-in from property owners within the boundaries of the proposed FRID. However, given the flood risk of the area, and the desire for access to the waterfront, these property owners stand to benefit from the interventions that would be funded by the FRID. It will be key to ensure that the process remains community-driven despite the need to appeal to landowners and potential developers. Importantly, Guardians of Flushing Bay may be able to leverage existing relationships with certain significant businesses in the area, such as U-Haul and Skyview Mall.

A similar adaptation of the BID model has been implemented by the Gowanus Canal Conservancy (GCC) via their Gowanus Improvement District (GID). The focus of the GID is to create a unified vision for the “public” park spaces being created by various developers along the Gowanus Canal. Funds for the GID will keep these spaces publicly accessible, install green infrastructure and other resilience interventions, and provide maintenance over time.

Map illustrating environmental vulnerabilities along the Creek

Vision for interventions to be implemented and maintained by BID funding

All actions taken by the GID are based on input from the community through surveying and public outreach. While there are key distinctions between the GCC and Guardians of Flushing Bay, their work offers a model on which to base the primary steps of implementing a resilience-oriented improvement district, and GCC would be a helpful resource for examining best practices, especially in building consensus.

The Gowanus Improvement District (GID) has been a several year process for GCC. The GCC had the advantage of momentum with the rezoning and EPA-led Superfund clean-up happening in Gowanus to get buy-in from the City and property owners. There is a similar turning point happening in Flushing, but the process would take a dedicated team to work on the application and develop buy-in.

Key steps:

Steps for implementing the FRID include determining its boundaries and determining how partners will be assessed. The proposed boundaries for the FRID catchment area are based on the projected 2050 100-year flood zone. Each census block area intersecting with that projected flood zone was selected for the FRID and included in its proposed boundary. Assessment categories should consider land use, the resources available to a specific business or building, and the extent to which they stand to benefit from additional resilience investment.

The funds generated by the FRID can be used to build out a team to manage the implementation of resilience interventions in the community. This team could be divided into two focal areas: (1) stewardship and community engagement and (2) maintenance and management.

With community approval, FRID funds could serve as leverage to fund the interventions recommended throughout this report, as well as provide direct funding. Its shared goals with the FADA Community Special District and a potential ESMIA would create constructive redundancies that encourage resilience in multiple facets and at multiple scales of intervention. Finally, specific resilience interventions mentioned in the rest of this report could be supported directly by funding or team support from the FRID.

Introduction: The Flushing Waterways Communities (FWC) are witnessing both hyper gentrification, leading to the displacement of working class residents, and continued development in flood vulnerable land. Within the 500-year floodplain, there are over 2,400 buildings and 101,200,000 square feet of land; that land includes almost 8,000,000 square feet of residential land use and over 8,000 housing units. Taking the high degree of rent burdened households into consideration, along with the potential for a large area of land to experience frequent flooding or be underwater in the future, this recommendation outlines the creation of a Flushing Waterways Community Land Trust (FWCLT) with a mission of conservation and affordability. A FWCLT can support multi-generational and sustainable land uses by creating community-owned affordable housing and acquiring flood prone properties to be stewarded by community members.

Vision 2100: A Flushing Waterways Community Land Trust (FWCLT) and resilient development framework exist. The development framework takes future floodplains into consideration and directs development to less flood-prone areas of the Flushing Waterways Communities. The FWCLT supports community ownership of land, providing affordable and storm resilient housing as well as facilitating the stewardship of underwater and frequently flooded land.

Project Description: A CLT can utilize land ownership to establish community education programs, create affordable housing, or protect and conserve land vulnerable to natural hazards. The FWCLT can acts as a “steward of the community’s land and guardian of the community’s interests” by being an embodiment of the Flushing Waterways Communities commitment to conservation and affordability. This enables community members to shape the landscape and use of land in a way that benefits the neighbors of the Flushing Waterways—the Creek included.

IMAGE 03B. Development Zone site (red) and Conservation Zone site (green)

The FWCLT would operate in two zones, directing affordable housing development to the “Development Zone” and stewarding flood vulnerable land in the “Conservation Zone.” The conservation zone (IMAGE 03A) consists of land in both the 500-year floodplain for the 2050s and the catchment area of the above proposed Flushing Resilience Improvement District (FRID). The development zone (IMAGE 03A) consists of land in the FWC neighborhood tabulation area boundaries that is outside of the 500-year floodplain. This is a proposed separation that would need to be further refined to consider existing conditions—whether it’s property lines, land use distinctions, or other social boundaries.

Development Zone Site: This vacant lot is between the land slated for the Special Flushing Waterfront District (SFWD) and a smaller vacant lot across College Pt Blvd. This smaller lot has not been developed since the last building was demolished in 2016, but it was recently purchased and is slated to be a transitional housing facility. However, members of the community are advocating for this property to be used for long-term affordable housing—once again demonstrating the need for affordable housing development in the area.

Since this selected site is currently zoned V1, the FWCLT would need to go through the traditional ULURP process to change the zoning and pursue residential land use. However, a land use change for this parcel is feasible given the context of the surrounding uses. Adjacent vacant lots are being developed with residential units and the site is next to a strip of residential lots. This parcel additionally sits just outside the boundary of the proposed Special Flushing Waterfront District, which will also introduce residential use. An R5 zoning would be consistent with surrounding residential uses and, based on allowable square footage of the building and allowable dwelling units, a 3 story apartment building with 8 units could be built. Qualification as Income-Restricted Housing Units in a Transit Zone reduces on street parking requirements.

Occupancy and use restrictions would be written into the FWCLT ground lease to preserve affordability. This allows for long term enforceability of regulations based on established principles and subsequent restrictions. In the event of a need to change the use, ground lease restrictions can be modified.

Address: 39-09 Janet Place BBL 4049620026

Owner: College Point BLVD Realty Corp (purchased in 1996, site has never been developed)

Lot area: 5,220 sq ft, Frontage: 60 ft, Depth: 87 ft

Image 03D. Elevation path (650 meters) along 39th Ave from Prince Street through the creek. Colors represent current land use (brown=commercial, gray=vacant, red=chosen vacant site). Max elevation is 47 feet and site elevation is 25-32 feet.

Image 03E. Elevation path (650 meters) along 39th Ave from Prince Street through the creek. Colors represent proposed 2100 land use (brown=commercial, yellow=residential, green=open space). Max elevation is 47 feet and site elevation is 25-32 feet.

Building Class: V1 [Vacant Land Zoned Commercial]

Owner: FWCLT

Lot area: 5,220 sq ft, Frontage: 60 ft, Depth: 87 ft

Building Class: R5; FAR 1.25; Height limit: 40ft / Street Height 30ft; Dwelling Unit Factor: 760 Building: 6,204 sq ft gross floor area; 3 story building with 8 dwelling units; 1,800 sq ft backyard; 600 sq ft front yard; two 376 sq ft side yards

Conservation Zone Site: Land acquired in the conservation zone will have resilience-oriented interventions while maintaining community ownership and maximizing community benefits. Flood prone land can maintain its value through coastal conservation and aquaculture. Community gardens can be developed and temporary structures can be introduced. Land in the conservation zone under the FWCLT can function as a location for the proposed Flushing Field Station programming and operations. There is a focus on incorporating the youth, drawing inspiration from Youth On The Move (a program through Woodside on the Move—an organization focused on housing and community development in Western Queens).

Useful CLT models for reference include Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI) CLT in Boston, MA; Bronx Land Trust and South Bronx Unite’s Mott Haven-Port Morris Community Land Stewards in the Bronx, NY. DSNI continues to successfully advance community development while preventing displacement through acquiring land that is used for affordable housing, parks, and gardens. The Bronx Land Trust has a mission of preserving community managed open space and they do this through maintaining almost twenty community gardens throughout the Bronx using a CLT structure. South Bronx Unite’s Mott Haven-Port Morris Community Land Stewards is a more recently established CLT that focuses on addressing environmental injustice and economic inequality. The FWCLT can get inspiration from their commitment to creating community green spaces and their Statement of Principles on Private Development.

Process: Establishing a FWCLT would follow a typical framework used for CLTs: Coalition building and visioning; determining mission; establishing a governance structure; forming a business plan; identifying and acquiring necessary resources; and land acquisition and site planning. Unique to this FWCLT would be establishing zones for specific land use and identifying regulations for use of that land based on principles identified in the visioning process. The FWCLT should couple the CLT model with proposed legislation that can support the pursuit of community-driven resilient development. For example, the FWCLT can leverage value capture and exactions in planned large development projects such as the SFWD.

Image 03F. Selected conservation site

Current Site

Address: 118-09 29 Avenue and 118-09A 29 Avenue, BBL 4043150040

Owner: 118-09 Associates LLC (purchased in 2005, site has never been developed)

Lot area: 6,102 sq ft, Frontage: 113+12 ft Depth: 54+100 ft

Building Class: V1 [Commercial]

Image 03G. Elevation path (300 ft) along 29th Ave to 119th St. Colors represent current land use (green=chosen vacant site, yellow=residential, gray=vacant). Max elevation is 21 ft and site elevation is 2-14 ft.

Image 03H. Elevation path (300 ft) along 29th Ave to 119th St. Colors represent proposed 2100 land use (green=open space). Max elevation is 21 ft and site elevation is 2-14 ft.

This section explores solutions for rehabilitating the ecology of the Creek and stewarding a more inclusive, accessible recreational environment for the Flushing community.

Project 04: Mitigating CSOs with Nature-Based Solutions Project 05: Wayfinding and Placemaking on the Creek Project 06: Flushing Waterways Community Land Trust

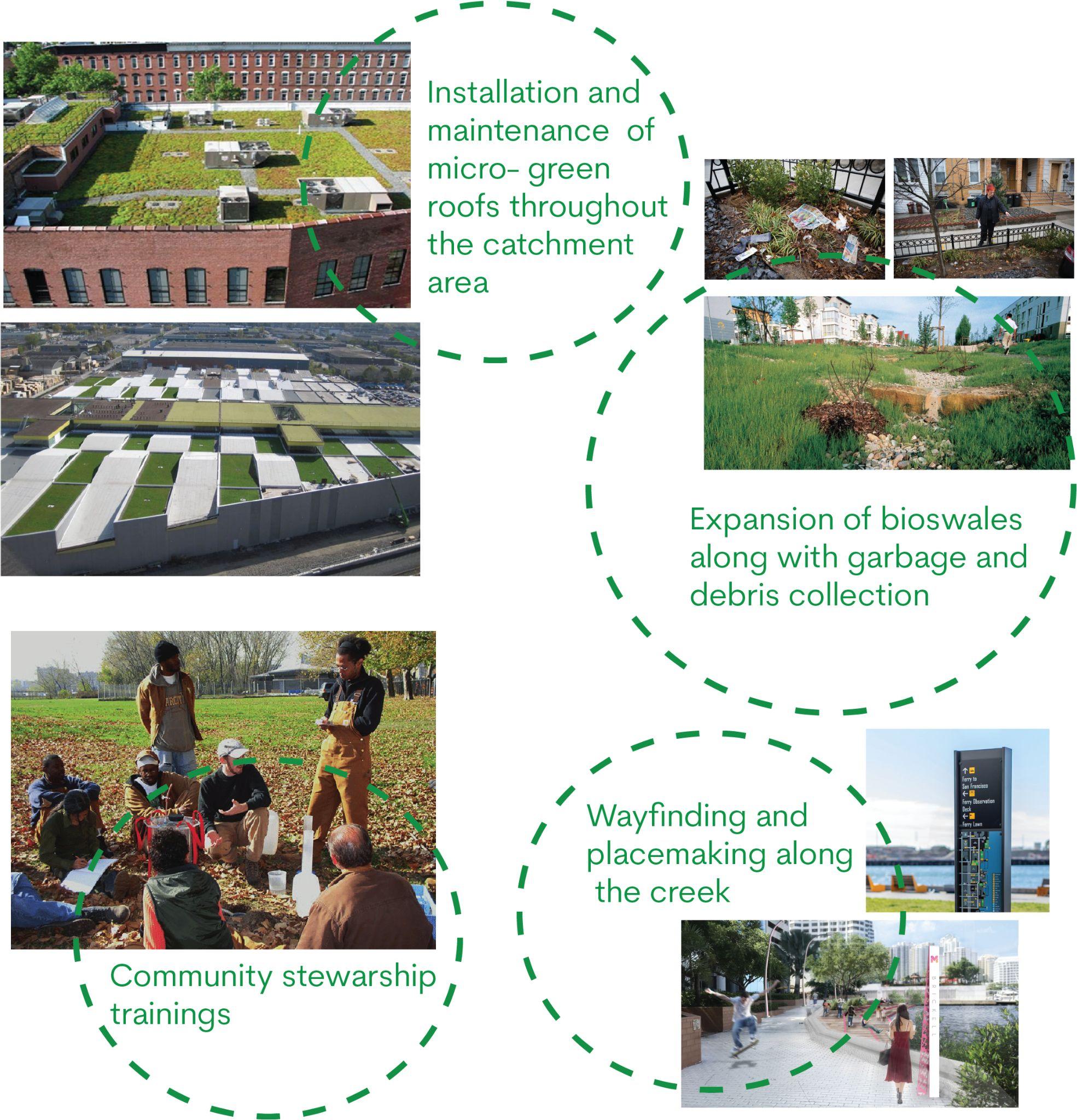

Introductions: While discussing the health of the creek and finding sources of pollutants that make the water unfit for swimming or fishing, one major source is vastly overlooked. This source is literally hidden from plain sight and takes form underground in the Combined Sewer Systems. Whenever there is an extreme rain event, the combined sewer system is overwhelmed and cannot contain the large influx of stormwater and hence, this excess along with domestic sewage and industrial wastewater is discharged into a nearby water body known as Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs). With the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events on the rise, this problem needs to be solved with measures that won’t create more problems than they intend to solve. The Guardians of Flushing Bay has been striving to make Flushing more resilient. Nature-based solutions for stormwater management and Green Infrastructure could help further this goal by providing with a plethora of co-benefits, such as, improve water quality for wildlife, restore wildlife habitat to the built environment, and invite beneficial species such as pollinating insects, birds and fish back to the places we live, reduce the adverse impacts of the greenhouse effect, etc. apart from reducing/mitigating the CSO outfalls. This project dives deeper into quantifying the potential of such strategies for Flushing.

Project Description: The main focus of this project is to analyze the extent of CSO outfalls that can be mitigated by incorporating Green Infrastructure and nature-based solutions for stormwater management in various typologies of projects. The focus was more so on public/government properties and on private properties (residential, commercial as well as industrial) that are larger than 25,000 sq.ft. And the scope was limited to studying three sewersheds; TI-010, TI-011 and TI-022. Bland Houses in Flushing was selected as a pilot site to specifically analyze the impact/potential that the different kinds of green infrastructure strategies might have for managing/retaining or temporarily storing stormwater. The following features were identified in the property for their potential to retain/manage stormwater on site;

● Parking that help the water percolate underground by the use of permeable pavers,

● Basketball courts that could be converted into a detention pond,

● Open Lawn Area that could be dug out and made into an open amphitheater with a rain garden,

● vast terrace area that could be made into a green roof.

The impact that these simple measures could have in reducing the stormwater load on combined sewers is immense. These results we then extrapolated for the target properties across the three selected sewersheds to determine the overall potential of the project.

Map showing all CSO Outfalls and Drain Areas around the Flushing Creek.

A modified plan of Bland Houses, Flushing showing all the Nature-based solutions overlaid on the site.

Phasing: The phasing of this project is designed to start the implementation of nature-based solutions/Green Infrastructure on site that are relatively easy to transform without disrupting any activity around the site first and then move on to more complicated project/solution types that may need more extensive involvement/resources from other stakeholders.

● Phase One: Redesign and redevelop parking lots and sports fields, both public and private.

● Phase Two: Incorporating Green Infrastructure in NYCHA properties and Public Facilities/Institutions.

Map showing all the target properties for incorporating Green Infrastructure and Nature-based solutions in TI-010, TI-011 and TI-022 Sewer Drain Areas.

● Phase Three: Private residential and commercial properties that have over 25000 sq.ft. of building area

A schematic section showing all the proposed solutions through the Bland Houses site leading to the Creek (Not true to scale).

The calculations in the table above prove that the amount of water that can be managed on site with these relatively simple and straight-forward strategies exceeds the combined CSO outfall from the year 2016 for the sewersheds TI-010, TI-011 and TI-022. With adverse climate events increasing at a pace that is difficult for us to keep track of or to fight against, it is imperative that we come up with solutions that can provide long-term relief and can, hopefully, tackle more than one problem at a time. Nature based solutions can do exactly that and more to make our neighborhoods and community more resilient. Most of New York City land used to be a marshland. Nature is asking for some of the land that we confiscated to further our needs and ‘development’ back and rightfully so. It is high time that we stop fighting against nature and make space for it to thrive as that would mean that humankind will too. We have operated on a human-centric mindset for centuries now. Let’s unlearn our selfish ways to protect and restore the scarce resources that are the heart of our communities (or for the case of Flushing Creek, ‘should be’ the heart of the community) and make space for it to flourish.

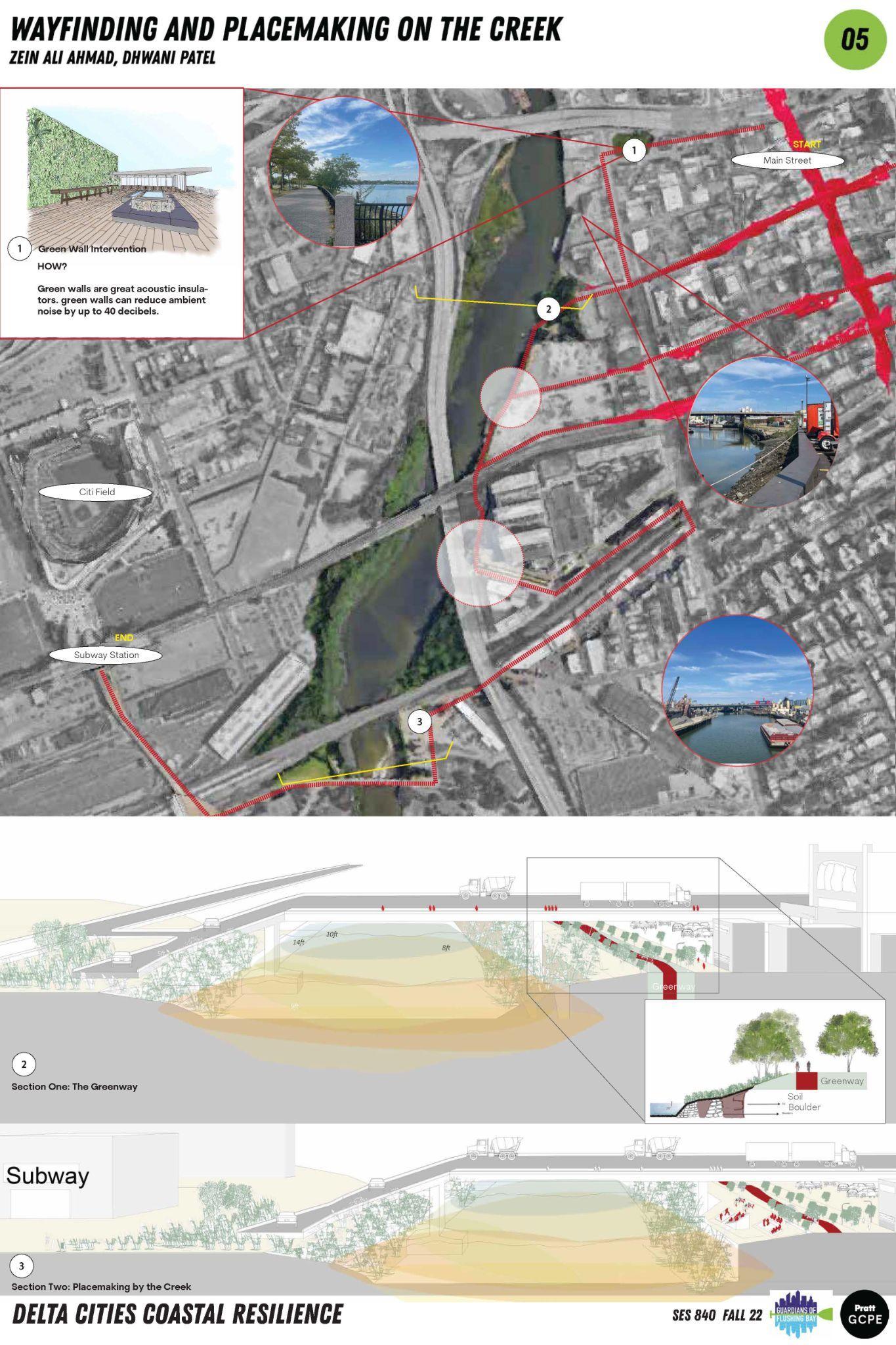

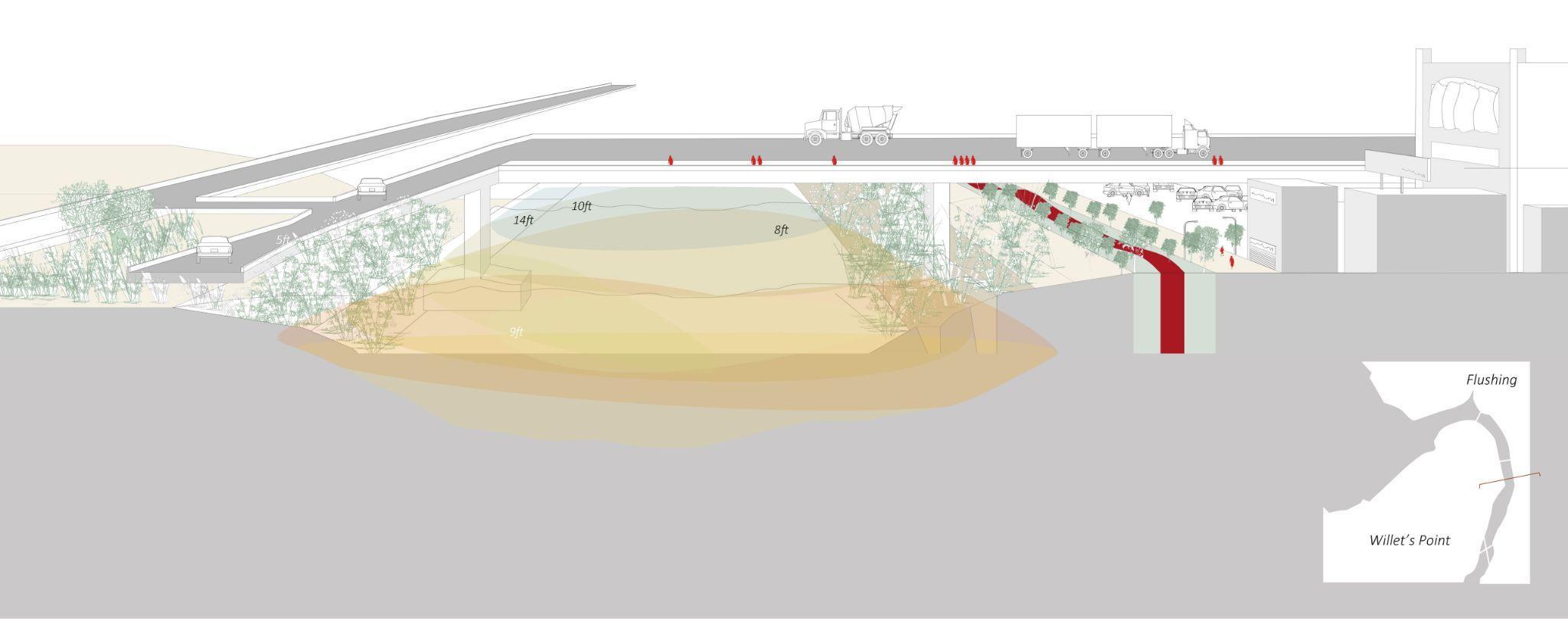

Flushing Creek is currently a neglected and heavily industrialized area, sandwiched between large governmental and manufacturing sectors. Throughout our many visits and engagement with the community of neighboring areas including Willets Point, Flushing and College Point, it was prevalent that most of the visitors and residents did not even know the creek existed. This project’s goal is to physically link residents and visitors to the creek. It serves to repurpose the current existing underserved edge into an inviting pedestrian greenway. This is through placemaking interventions, wayfinding elements and a pedestrian greenway linking Main Street on the Flushing side to Mets-Willets subway station across the creek with specific resiliency measures targeted along the way.

Flushing Creek has the potential to serve as a linear park, using trails to connect plazas and create pedestrian-friendly transit corridor as a source of recreation for the entire community. If an appropriate trail network is established, it can eventually improve the quality of life for those in the area. Inviting neighbors to gather and revitalize the streams through the installation of a canopy, grill, tables, and sitting walls. This is a step toward achieving the objective of expanding opportunities for outdoor leisure and relaxation in these underutilized areas. It offers the local community a sense of pride and security in the public trails and waterways by providing many access points to them.

Offering water features, biofiltration of urban runoff in specific areas along the creek, and a long greenway linking the top of Main Street to Mets-Willets Point subway station creates a sense of identity for Flushing’s residents. The aim is to reintroduce Flushing Creek as a focal point rather than a forgotten and underserved space.

Green Wall with Recreation : This area is adjacent to a Concrete Manufacturing Plant and also a highway. It will be an open space with Green walls as they are great acoustic insulators and have been shown to attenuate outside noise by up to 40 decibels. The space will be utilized for public gathering and social activities.

Green Way with Native Plantations : Proposed Greenway will comprise of a Trail and a bike way, as well as Integrated rain gardens with drought-resistant native plants for the purpose of ecosystem restoration, improving the area's environmental quality.

Corona Park Tip: The proposed area will be a Plaza facing the creek. It will act as a bio-filter for Stormwater. By adding canopy, tables and seating it will bring people together and energize the creek.

Plants and trees have been used as noise barriers against traffic and other sources of urban noise pollution for decades. The Green walls protect against noise and vibrations and minimize sound transmission. In addition, they absorb the echoes of buildings, noisy highways and reduce the noise pollution of modern cities. Green walls are great acoustic insulators and can reduce ambient noise by up to 40 decibels.

The Green way will Protect vital habitats and provide animals and humans with corridors. They also enhance the quality of air and water. Trails will provide fun and secure mobility choices, hence reducing air pollution.

Ecosystem Restoration with integrated rain gardens and drought-tolerant native vegetation - A number of small rain gardens would take advantage of nearby run-off and provide planting spaces, increasing the corridor's environmental quality. Now, rainwater collects on the streets and flows directly into nearby creeks. Slowing runoff using measures like rain gardens, bioswales, and upgraded outfalls increases groundwater recharge, enhances water quality, and allows for more plant life to thrive. This, in turn, enhances shade and maintains the plazas' aesthetically pleasing landscaping. Comfort may be increased with a shade shelter, and it also serves as a fantastic focal point for interacting with the larger design community. Together, these might provide emergency cover at various points.

In 2100 Flushing, Queen’s working waterfront can be a beacon of industrial ecology, regenerative working waterfronts and nature-based solutions for armoring its shorelines against storm surges and sea level rise while ensuring the Flushing community has access to jobs and a vibrant, sustainable economy and environment. This project outlines steps to support and encourage a just transition for the Creek’s working waterfront including workforce development opportunities, tools for decarbonizing industries along the Creek, water quality remediation, and shoreline protection. The revitalization of the Creek and its industries should grow analogously and represent a circular, decarbonized economy and the ideals stated in the Jemez Principles.

Over the past sixteen years more than twenty-four million tons of products have moved through the Creek (NYCDCP, 2021). Most of this is sand and gravel, key materials in manufacturing concrete and asphalt; the main industries along both sides of the Creek. Cement production contributes between seven and eight percent of CO2 globally and its use is expected to continue to grow until 2050 (The Economist). Recently announced Executive Orders on the Federal, State, and Local level are supporting low-carbon cement (The White House, 2022). These orders, in tandem with the State’s Low Embodied Carbon Concrete Leadership Act (LECCLA), offer various incentives for manufacturers to lower emissions. This project explores how concrete manufacturers might tailor their businesses toward providing low-carbon concrete for eco-engineered, resilient coastal infrastructure that will be less injurious to the environment.

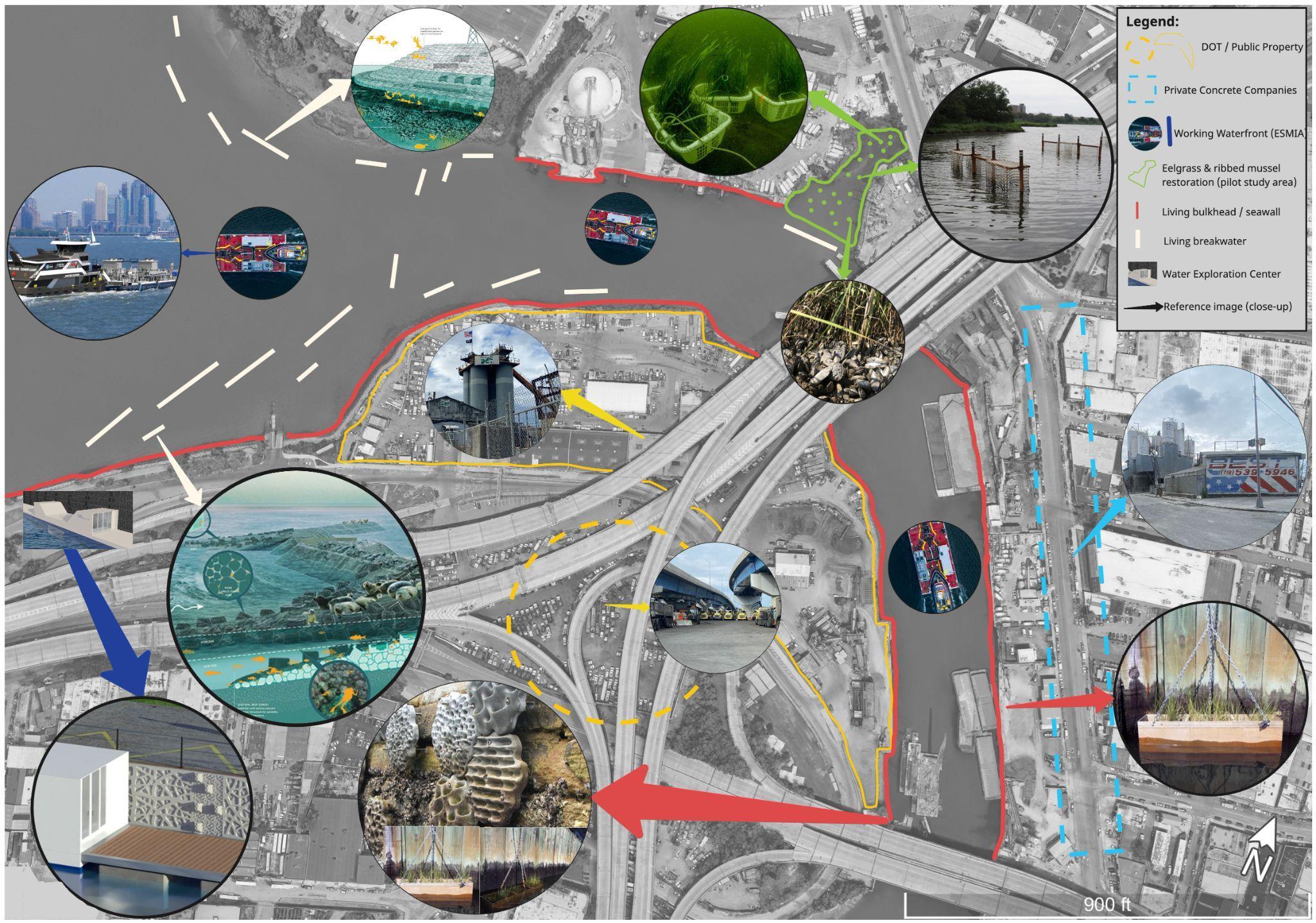

Innovative, low-carbon concrete is requisite for constructing living seawalls and breakwaters, and other critical resilient infrastructure. Living seawalls support marine habitat restoration by attaching 3D-printed molds to concrete walls which mimic native structures Garden, 2022). Living Breakwaters is another novel eco-engineering concept and currently under construction off the south shore of Staten Island (GOSR, 2022). These adaptive eco-engineering projects should be seen as an alternative to relying solely on engineered seawalls proposed by the US Army Corps of Engineers’ (USACE) “NY & NJ Harbor & Tributaries Feasibility Study” (HATS) and can be manufactured in NYC.

Maintaining Flushing Creek’s status as a working waterway is vital to its present and future economic character. Harbor freight reduces polluting truck traffic and is in alignment with DOT and NYC-EDC’s Marine Highways plan (NYCDOT). However, this does not mean the Creek’s water quality should remain stagnant. Eelgrass and spartina restoration, ribbed mussels, kelp lines, and oyster cages should be implemented in stages in non-navigable portions of the Creek and Bay to remediate water quality, mitigate storm surge events, and provide habitat for other marine species. Focusing first on eelgrass and ribbed mussel restoration through pilot studies in a location determined to have an ideal tidal gradient and easy access, aquaculture can slowly expand throughout the area, ultimately introducing commercial species (sugar kelp, oysters) and developing aquaculture zones for a more streamlined approval process (Brown, 2022). What’s more these studies can be incorporated into redesigning the bulkheads along the east and west sides of the navigable channel of the Creek to be “living bulkheads” which feature a mosaic of life akin to Living Breakwaters and the innovative seawalls in Sydney Harbour designed by Reef Lab (Gillespie; GOSR).

This project is an extension of the Flushing Resilience Improvement District (FRID) and the Flushing Field Station. The FRID will be a critical framework to realizing this project’s reimagined concrete industry and the concept for aquaculture pilot studies and aquaculture zones. Further, this project articulates the need to rezone the Creek from a Priority Marine Activity Zone (PMAZ) and Special Natural Waterfront Area (SNWA) into a ESMIA (Ecologically Sensitive Maritime and Industrial Area), to support both its industrial and ecological needs. This project demonstrates, from a workforce and consumer point of view, how elements of the FRID can be actualized.

The Flushing Field Station, and the Waterfront Exploration Center (initially conceptualized by RiverKeeper and Guardians of Flushing Bay’s 2018 Vision Plan) are important partners for this project as well. Flushing’s Oval-Blue Economy depends on a skilled local workforce to help construct and maintain nature-based, resilient coastal infrastructure. Moreover, the Field Station can help to introduce students and aspiring marine scientists to take part in the initial eelgrass pilot studies, while inspiring others to advocate for and apply for aquaculture permits in future phases of this project. Stakeholder Map

The third component of this plan focuses on education and community engagement to expand the surrounding community's awareness of the relationship between the creek's wellbeing and their own.

Project 07: Flushing Field Station Project 08: Democratic Data for Empowerment

Expanding the surrounding community’s awareness of the relationship between the creek’s wellbeing and their own is key to driving sustained interest and investment in ecological health and resiliency. While the creek has had a significant impact on the community, it is often overlooked as a physical feature due to its inaccessibility. Guardians of Flushing Bay and their partners have worked to improve access to the creek through guided tours and unofficial trail guides, and now there is an opportunity to create a physical landmark to center these activities and give community members a focal point for their engagement with the creek.

We are proposing the creation of a Flushing Creek Field Station to serve as this focal point. The field station will serve as a physical marker and a gathering point for Guardians’ in-the-field activities, as well as a distribution site for literature related to the creek’s history, ecology, and climate risk. The Station would be a built manifestation of the need to bring residents together to preserve and protect the creek and its ecology.

To start, the Field Station could be housed within a small building or shipping container adjacent to the creek. In the future, and with additional funding through grants or partnerships, the Field Station could expand into a Resilience Center embedded within the community.

From a functional standpoint, the Field Station would be a hub for information about the creek and the surrounding communities. Inspired by the popup health stations set up in Buenos Aires, the Field Station would compile all of the resources and literature that Guardians has already created, as well as the resources generated by other proposals offered by this studio, into a single distribution hub. These materials would cover topics ranging from creek history, to an overview of creek ecology and the threats facing these habitats, to disaster preparedness materials that could help the creek’s neighbors understand how to respond in instances of stormwater or tidal flooding. In addition to disseminating information, the Field Station would have a dropbox for resident ideas or feedback about the experience of living near or accessing the creek. These ideas could then be incorporated into future materials and programming produced by Guardians.

While the Field Station could begin as a small installation alongside the creek, this would be the first step in a process of cementing the connection between the community and the creek. In the future, the Field Station could serve as a satellite office for a centralized Flushing Creek Resilience Center, operating out of a storefront or office space in downtown Flushing. This larger, more well-resourced space would allow Guardians to conduct further research into the creek, with experiments like soil or water analyses serving simultaneously as public displays to educate community members and key data points in policy advocacy. It would also serve as a gathering point for the community to collectively address climate risk and strategize for the stewarding of the creek. Finally, Oval-Blue Economy seminars and trainings held at the Resiliency Center could dovetail with programming occurring at the Field Station, offering a network of opportunities to connect with the creek and build capacity for the necessary work of restoration and growth.

Community-led development and change requires significant resources. Successful initiatives depend on several factors, including a community’s ability to organize, define their priorities across groups, and communicate strong and clear wants and needs to various stakeholders and decision-making entities. Accurate, equitable, and accessible information is critical to empower residents and community leaders to advocate for visions backed with truth.

Geospatial data is fundamental in understanding context, as it has the capacity to communicate quantitative and qualitative information in a visual format that is easily understood by people in place.

GoFB has expressed there is a lack of climate resiliency data representation for the waterfronts in Flushing. Since this area’s conditions are underrepresented, they tend to get overlooked in policy and planning decisions. By creating an online platform, as well as several geospatial and statistical visualizations, we aim to increase advocacy for the Creek and allow GoFB, as well as their partners, to present solidified evidence both in government meetings and public outreach events. This dashboard can be expanded with additional social and political geospatial layers.

Our Vision is to provide the necessary tools to ensure that balance is restored to Flushing Waterways, include the existing community as an integral part of positive change, and make participatory mapping an accessible medium during community engagement.

Our grounding truths are that Knowledge is power. Access to data is empowering. Nothing about us without us is for us. There is justice in knowing what is happening around you. There is power in having the ability to shape an outcome.

Our intention is to provide a framework to make data not only easy to access by the community, but also that the community is empowered to participate in gathering the data, and take tangible steps towards meaningful change.

This becomes a tool for…

Our process is to make it simple for GoFB and its Board of Directors to facilitate the creation of the dashboard by collaborating with data managers and specific organizations such as SAVI.

Visualizing the intersection between environmental social and political data, highlighting existing inequities and leading to change.

Advocacy by creating clear, usable tools that are easy to access, incorporate into campaigns, and communicate the story of the creek and community.

Community members to have the capacity to form coalitions that lead to more equitable outcomes, such as mandatory EIA studies and spatial equity techniques.

…We begin to observe

Value Systems Shift: The community understands their rights TO nature AND The rights OF nature are realized and upheld

Narratives shift. There is more discussion about practices and policies with harmful impacts to the community and environment. There is increased public support for ecological preservation and equitable access.

Power Systems Shift: Development, maintenance, and use of geospatial data is democratized, leading to accessible and accurate information, which empowers the community to shape the outcomes of their landscape and place.

PPGIS is a technique where GIS technology is used to support public participation for a variety of applications with the goal of inclusion and empowerment of marginalized populations. It is designed as an additional layer to complement expert analysis, and helps facilitate two-way dialogue between scientists and stakeholders (Morse et al. 2020).

Spatial value typologies are determined based on local values and preferences. Spatial surveys are developed to maximize community responses and input. Throughout the engagement process, respondents create new datasets by matching social, cultural, and ecological values with locations on maps.

Participant-identified points are visualized spatially, creating new maps and datasets for the dashboard. The new data is visualized in relationship to existing variables such as sea-level rise projections, heat islands, anticipated developments, zoning, public health, political boundaries, and more.

The dashboard facilitates discussions between stakeholder groups, and serves as a foundational resource for advocacy and education programs. Participatory mapping is an ongoing process, and the online data dashboard continues to guide conversation and climate-resilient recommendations.

The combination of high-tech and participatory approaches has been difficult, for GIS and other digital information technologies are viewed by some as capital intensive, complex to use, and expert driven (Lane et al. 2015). In this recommendation, we aim to address these challenges through a continued community-university partnership. Expanding the relationship with Pratt and GoFB, as well as introducing SAVI into the partnership, can allow Guardians to have a greater capacity to complete the framework outlined in this recommendation. An ArcGIS online account for GoFB will be facilitated at the beginning of spring semester.

As emerging planners, it was a privilege to work so closely with Guardians of Flushing Bay and be able to explore radical strategies of rethinking traditional planning in a delta city community such as Flushing. The studio’s existing conditions research identified specific strengths and challenges within this site, including increasing flood vulnerability and ecological sensitivity, but also a strong community invested in the wellbeing of Flushing Bay and Creek. This is an area where speculative development is rapidly transforming a landscape that has a long history of being in flux, and of being manipulated to serve human interests. The health of the Flushing Waterways as well as the health of the community have been damaged by this history.

In developing and reporting our recommendations, we focused on policy and planning, environmental systems and placemaking, and community engagement and education. Each of our recommendations overlap and link in ways that can continue to evolve going forward. Primarily, these recommendations are meant to serve the interest of the community, especially considering its resilience to climate change impacts and improving ecological health.

The vision of the Flushing Waterways in 2100 presented in this report is one of healing and community building. In this vision, forgotten water bodies have become central to the surrounding community, and are allowed to flourish. The local economy is rooted in the health of these aquatic ecosystems, and that health in turn feeds into the wealth of the community. The rights of the flora and fauna of this ecosystem have been re-established and the community members are empowered to steward the land in a holistic, engaged way. This work joins previous DCCR projects that uphold and adapt the ideas behind the original Delta Cities Coastal Resilience studio vision.

NYC Open Data (2022) 2010 Census Tracts [.shp]. Retrieved from https://data.cityofnewyork.us/City-Government/2010-Census-Tracts/fxpq-c8ku

NYC Open Data (2022) 2010 Neighborhood Tabulation Areas (NTAs) [.shp]. Retrieved from https://data.cityofnewyork.us/City-Government/2010-Neighborhood-Tabulation-Areas-NTAs-/cpf4-rkhq

NYC Open Data (2022) Borough Boundaries [.shp]. Retrieved from https://data.cityofnewyork.us/City-Government/Borough-Boundaries/tqmj-j8zm

NYC Open Data (2016) Green Spaces [.shp]. Retrieved from https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Recreation/Green-Spaces/mwfu-376i

NYC Open Data (2018) Hydrography [.shp]. Retrieved from https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Environment/Hydrography/drh3-e2fd

NYC Open Data (2022). NYC Street Centerline (CSCL) [.shp]. Retrieved from https://data.cityofnewyork.us/City-Government/NYC-Street-Centerline-CSCL-/exjm-f27b

US Census Bureau (2020). ACS 5-year Estimates (2016-2020). Retrieved from socialexplorer.com

US Census Bureau (2020). Census 2020 - Preliminary Data. Retrieved from socialexplorer.com

US Census Bureau (1960). Census 1960. Retrieved from socialexplorer.com

Matinecock Tribal Council. (n.d.). A History of The Matinnecock(sic) Indians. Retrieved from http://www.matinecocktribalnation.org/a-history-of-the-matinnecock(sic)-indians.html

Macaulay Honors College at Baruch. (n.d). Early History: The Swamp and Ash Dump. Retrieved from https://eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu/munshisouth10/group-projects/flushingmeadows/flushing-meadows-past/

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. (1833). Flushing Bay, Long Island with "Palisades" in the distance Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-4f93-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Fowler, and D. Bremner Co. (1876). Flushing, N.Y. Long Island 1876. Retrieved from http://digitalarchives.queenslibrary.org/browse/flushing-ny-long-island-1876

Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. (1909). Flushing Bay, Long Island, New York. Surveyed in compliance with river and Harbor Act. Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/f4f00b50-0dbb-0131-c767-58d385a7b928

Eugene C. Nichols. (after 1906). Wahnetah Boat Club, Boating Race on Flushing Creek [photograph]. Retrieved from http://digitalarchives.queenslibrary.org/browse/wahnetah-boat-club-boating-race-flushing-creek

Borough President of Queens. (ca. 1930). Flushing Creek [photograph]. Retrieved from http://digitalarchives.queenslibrary.org/browse/flushing-creek-2

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Art and Artifacts Division, The New York Public Library. (1934). Macedonia A.M.E. Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/34c85050-2893-0132-2c34-58d385a7bbd0