17 minute read

Capitalism Must Reform to Survive

from Jared Kushner to Majalla: “If Palestinians Come to the Table, the U.S. Will Be Flexible”

by المجلة

conomy E

Capitalism Must Reform to Survive

From Shareholders to Stakeholders

by Klaus Schwab

Companies today face an existential choice. Either they wholeheartedly embrace “stakeholder capitalism” and subscribe to the responsibilities that come with it, by actively taking steps to meet social and environmental goals. Or they stick to an outdated “shareholder capitalism” that prioritizes short-term profits over everything else—and wait for employees, clients, and voters to force change on them from the outside.

This assessment may seem harsh coming from someone who has always believed in the pivotal role companies play in the global economy. But there is no alternative. Our ecological footprint has expanded far beyond what the earth can sustain. Our social systems are cracking. Our economies no longer drive inclusive growth.

Today’s younger generations simply do not accept that companies should pursue profits at the expense of broader environmental and social well-being. We know that a free-market economy is essential for producing long-term development and social progress. We should not want to replace that system. But in its current form, capitalism has reached its limits. Unless it reforms from within, it will not survive.

FROM SHAREHOLDERS TO STAKEHOLDERS

Last year, the Business Roundtable, an organization representing many of the largest American companies, announced that it wanted to move away from shareholder primacy and toward a commitment to all stakeholders. It redefined the purpose of a corporation to promote “an economy that serves all Americans”—not just those who own shares.

The CEOs signing the Business Roundtable statement were a veritable Who’s Who of American capitalism. As chair of the Business Roundtable, JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon was the first to endorse it. Among the 181 signatories were also Alex Gorsky of Johnson & Johnson, Ginni Rometty of IBM, Mortimer J. Buckley of Vanguard, and Tricia Griffith of Progressive.

The announcement was met with mixed reactions. Some saw it merely as a maneuver to preempt pressure from an ascendant left. Others dismissed it as disingenuous, a mostly symbolic move without concrete actions to back it up. How can a company claim to have implemented a major change, asked skeptics, if its quarterly reports still focus on maximizing the financial bottom line?

A protestor holds a sign at a demonstration against climate change where climate activist Greta Thunberg addressed a multitudinary crowd on January ,17 2019 in Lausanne, Switzerland. The protest is taking place ahead of the upcoming annual gathering of world leaders at the Davos World Economic Forum. (Getty)

But such skepticism misses how significant the shift is— and the opportunity to turn it into real change. Since 1997, each previous set of principles endorsed by the Business Roundtable had put shareholder primacy first. For the group to drop that principle was revolutionary. But it is also true that unless these words are translated into collective actions, the revolution will be short-lived.

WHAT IS THE CORPORATION?

So what can be done to ensure that the move to stakeholder capitalism is real and lasting? To answer that question, it is worthwhile looking back to the postwar global economic system and the role played within it by companies, governments, civil society, and international organizations. Some may think Western capitalism has always put shareholders first. That is not so.

The World Economic Forum was founded five decades ago in Davos to promote the “multistakeholder concept”—a model that had grown out of my knowledge of both the European and the American approaches to capitalism. U.S. companies

in the postwar era had perfected business and financial management, optimizing for growth and profits. It made American companies and American management thinkers the envy of the world. But European managers at the time were also getting something right. They had a social reflex, evident in a deep commitment to their workers, clients, and suppliers. As an engineering student, I had worked on the shop floor in several factories. Spending time with my fellow workers confirmed to me that blue-collar workers are just as bright, and add just as much value to a company, as their white-collar peers or the shareholders of the companies they work for.

conomy E

my 1971 book, Modern Enterprise Management in Mechanical Engineering) inform the Davos Manifesto signed at the newly created World Economic Forum. The manifesto’s opening line declared that “the purpose of professional management is to serve clients, shareholders, workers, and employees, as well as societies, and to harmonize the different interests of the stakeholders.”

The Davos Manifesto was rooted in recent postwar experience, but it was also a restoration of a longer historical arc. Companies have always been social units as well as economic units. Indeed, corporations were first created in medieval Europe as an independent vehicle to achieve economic progress but also to create prosperity for society or to build institutions for the public good, such as hospitals and universities—what we now call “shared value.”

But this vision of the corporation was not universally embraced. Around the same time, the University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman put forth a very different vision. “There is one and only one social responsibility of business,” he wrote, and that is “to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits.” The business of business, in short, was business. The idea of shareholder primacy was born. Before long, it was embraced by the Business Roundtable and other leaders in the field.

INCONVENIENT TRUTHS

For the next few decades, it appeared that shareholder capitalism really was superior to stakeholder capitalism. U.S. companies increased their dominance, and shareholder primacy became the norm in international businesses. No

U.S. companies in the post-war era had perfected business and financial management, optimizing for growth and profits. But European managers at the time were also getting something right. They had a social reflex, evident in a deep commitment to their workers, clients, and suppliers.

person captured the atmosphere better, perhaps, than Michael Douglas’s Gordon Gekko in the film Wall Street. “Greed, for lack of a better term,” he said, “is good.” His words were fiction, but many in the business and financial world agreed.

But the high growth of the 1980s, the 1990s, and the early years of this century masked some inconvenient truths. Wages in the United States started to stagnate from the late 1970s onward, and union power significantly declined. The natural environment deteriorated as the economy improved. And governments found it increasingly difficult to gather taxes from multinational corporations. All those problems have combined in the current crisis—and the only viable response is a turn back to the stakeholder capitalism that the shareholder model displaced.

In the four decades since 1980, economic inequality of all forms has significantly increased. In the United States, most notably, inflation-adjusted income growth within the bottom 90 percent has been virtually zero, while incomes of the top 0.01 percent have risen more than fivefold. Wealth inequality has grown even more. And the trends are similar, if sometimes less pronounced, virtually everywhere else in the world. In the 1960s, a CEO might earn 20 times what his workers earned. Today, American CEOs earn on average 287 times the median salary.

36 31/01/20 An empty trading floor is seen after the closing of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) on January ,10 2020 in New York City. (Getty)

would not be facing a climate crisis today. According to the Global Footprint Network, 1969 was the last year in which humanity’s ecological footprint was small enough to be sustainable. Since then, we’ve consistently exceeded this limit. Now, in 2020, we use resources at almost twice the sustainable rate.

A LAST CHANCE

change in their relationship to communities and governments. Whereas companies were once deeply embedded in the communities where they operated, those connections have diminished over time. As they cleverly exploit intellectual property and global transfer pricing, many companies— driven by profit maximization—have become less reliable taxpayers. And as the financial sector has grown in a way that is increasingly decoupled from real economic growth, it has pursued short-term results to the detriment of long-term sustainability.

The overall result has been a deterioration of the bond between business and society. And governments, faced with fresh social and economic challenges, are often unable to make the investments that are needed, deprived as they are of necessary tax incomes.

Finally, and perhaps most important, the environment has continued to suffer as a result of economic activity driven solely by profit maximization. This, too, was a concern as early as the 1970s. At Davos in 1973, the Club of Rome’s Aurelio Peccei spoke of the imminent “limits to growth.” And the Davos Manifesto noted that management “must assume the role of a trustee of the material universe for future generations” and “use the immaterial and material resources at its disposal in an optimal way.”

We now know that if our use of the world’s natural resources had remained at early 1970s levels, we probably As young people from around the world have been reminding us of late, now is the time to rectify our historical error. The only way to save capitalism is to return to—and double down on—the stakeholder model we discovered, and then forgot, decades ago. But with the social, economic, and environmental situation now several times worse than it was, we’ll more than ever need to make changes that go beyond mere words. How can we do this?

To start, companies and their shareholders must agree on a long-term vision of their objectives and performance, rather than let quarterly results dictate everything. From there, companies must make more concrete commitments to pay fair prices, salaries, and taxes wherever they operate. And finally, we have to integrate environmental, social, and governance measurements into formal business reporting and auditing systems.

These steps will require major changes. But the alternative will be even more difficult and potentially disruptive. Companies will be forced by new generations of workers, consumers, and voters to change their ways, whether or not they want to. Many companies, rejected by these groups, could slowly wither away. Or governments could take a heavier hand in enforcing new norms, reasserting themselves as the leviathan referee in markets.

If companies want to avoid such scenarios, 2020 will be a pivotal year. At the World Economic Forum, we will continue to advance and advocate for stakeholder capitalism, with the concrete commitments to make it inclusive and sustainable. This may be our last chance to reform capitalism from within. We should take it.

ulture C

If the Oscars Aren’t Going to Change, Is it Time to Walk Away? How the Academy Still Marginalizes Women and P.O.C

by Nina Metz

How do you solve a problem like the Oscars?

“Female filmmakers and actors of color increasingly sidelined,” is how the New York Times put it in the run-up to nominations. That prediction was confirmed earlier this month when a number of worthy names were noticeably missing from the list of contenders.

This year is the 92nd Academy Awards ceremony. In that history, only five women — all white — have been nominated for a best director Oscar. Ever. This year there are zero. And it’s not because of a lack of notable films.

Despite a concerted effort by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to add more people of color and white women to its membership in recent years, they still remain a vastly smaller segment of voters (%32 women, %16 people of color) compared to white men.

Sometimes the media is complicit in reinforcing the status quo. The New York Post recently published a story (“Academy members viciously reveal why Lopez, Sandler, Murphy got snubbed from Oscars”) that failed to challenge any of the nonsensical assertions from its quoted (and in most cases anonymous) sources. One Academy member told the paper that the expertly shot “Hustlers” was “a little too rough around the edges” and therefore not an Oscar movie. And yet the equally “rough around the edges” story told in “Wolf of Wall Street” — a multi-nominee in 2014 including best picture — clearly was an Oscar movie, whatever that even means?

Or consider this explanation for the snub of “Dolemite is My Name” star Eddie Murphy: “Some voters disliked how hard he seemed to be campaigning for a nomination, including hosting ‘Saturday Night Live,’ after giving his old show the cold shoulder for 35 years.”

Openly campaigning during awards season is nothing new. It’s remarked upon all the time. But Eddie Murphy returning to host “SNL” — the show that launched his career — is a bridge too far? You know who else hosted “SNL” in late 2019? Scarlett Johansson, who was nominated not just one but twice this year, for “Marriage Story” and “Jojo Rabbit.” These excuses are ridiculous and we in the media shouldn’t validate them. So what’s the way forward?

There’s a petition on change.org started by pop culture writer Kayleigh Donaldson calling for Academy

In this handout provided by A.M.P.A.S., Oscar statues are seen backstage during the 91st Annual Academy Awards at the Dolby Theatre on February 2019 ,24 in Hollywood, California. (Getty)

president David Rubin to “publicly announce a plan to fix the Oscars diversity problem” and to announce that plan at this year’s ceremony.

“Someone at Change reached out to me,” Donaldson said when contacted earlier this week, “and asked if I’d be interested in doing something more direct in opposition to the Academy’s consistent shutting out of women directors and I thought a petition would be more tangible than me constantly screaming about it on Twitter!

“2019 was such a brilliant year for women directors,” she added, “not only in that they made amazing films but that they worked on critically and commercially successful films that were part of the awards conversation and perfectly fit the often smothering mold that the Academy and the film industry at large demands of ‘prestige cinema.’” And yet, “it still wasn’t good enough. The goalposts are always moved further and further away, and it stung to see how pathetically predictable yet another all-male best director line-up was.” So what kind of solution does she have in mind? “I know that asking for specific aims on a topic like this

ulture C

can be tricky,” she said.

“I admit that I don’t have a detailed plan for their future. But I also think it’s sad that such institutions and the people within them don’t have one either, especially when they have all the resources at their fingertips. These (people) are supposed to be the best and brightest in their field, representing the group that positions itself as the peak of Hollywood glamour, history, and importance, so surely they’re not entirely devoid of ideas … (and) I do firmly believe that making the people involved fully confront the issue and commit to change on the record will have a tangible impact. And it will also force the industry around it, from actors to producers to publicists and journalists and beyond, to confront their own biases and make important shifts that will ripple throughout.”

What if instead of hoping for change, it’s time to reject the Oscars altogether? That’s an idea writer Nylah Burton explores in a column she wrote for the digital publication Wear Your Voice: “I say divestment is the best option,” she writes. “If the Oscar’s discernment has proven to be basically useless, then stop assigning worth to the awards they give out. Refuse to submit your work to the Academy for consideration. Promote other, more equitable film festivals and award shows. Or work together and start your own.”

She doesn’t just mean don’t submit work for Oscar

consideration — don’t participate at all, and that includes being a presenter or announcing nominations in the future. “The Oscars wants to stay white, and straight. So let them,” she writes.

Consider the kinds of roles women of color are typically nominated for — “Harriet” star Cynthia Erivo is the only non-white nominee in the acting categories this year — and which parts are overlooked.

Lupita Nyong’o playing double roles that are two sides of the same coin in the “Us”? No nomination. Alfre Woodard as a prison warden in grappling with the emotional toll of overseeing yet another execution in “Clemency”? No nomination. Jennifer Lopez as a charismatic exotic dancer who turns the tables on her clients in “Hustlers”? No nomination. The list goes on.

“An award nomination seems to depend on whether the role is deserving of white pity,” according to Beatrice Loayza writing in the Guardian, pointing out a blatant trend: “That the same types of roles — slaves, nannies and maids — continue to be the magic ticket to the red

40 21/09/19 Cynthia Erivo attends 26th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards at The Shrine Auditorium on January 2020 ,19 in Los Angeles, California. (Getty)

carpet feels particularly ugly considering the range of parts played by white nominees.”

“I think those movies make white people feel good because they feel so far removed from it,” Burton said by phone. “Like, ‘That happened way back, and isn’t is so inspiring that now the person who shares my cubicle is black?’

“It’s not a crime to be inspired or see those films and be moved by them,” she said. “But I do think they’re celebrated more because they allow people to feel like racism is a thing of the past.”

Maybe, she added, “it’s hard (for white audiences) to recognize when a black person is giving a good performance if it doesn’t revolve around their oppression or their struggle — maybe it’s difficult for them to even identify with it because the way they’ve been taught to identify with black people centers around either our oppression or some stereotype of us. Or our relationship to white people. Or our relationship to each other, like Tyler Perry films, that portray us in ways that white people are comfortable with.” I was curious if Burton thinks enough people could really be convinced to divest from the Oscars.

“Probably not,” she said. “It’s a hard decision and I get that. And I can’t even say if I were a filmmaker or an actor that I would even have the strength to make that decision.

“There’s a significant benefit to being involved with the Oscars that can’t be understated. We can say ‘You should divest’ but in reality that could harm people’s careers. The hostility that they might face from the rest of the industry, that’s a lot to risk. I think it’s scary to take a stand this concrete and shocking, and not everyone feels they can do it. And it would take a lot of organizing and who’s going to organize it? Who’s going to convince people to do it?

“Also there might be a lot of people who don’t actually see it as a big problem — that they’re so desensitized to it that they think everything is fine.

“But for me, from the outside looking in, it just seems like this is a way to make a powerful statement: I’m not going to submit my film for nomination. Don’t enable it, is basically what I’m saying. And it would almost give those films (that were snubbed) even more recognition if they stood together that way. Like: This is something we’re not going to do.”

The Oscars retain their credibility and legitimacy precisely because we — Hollywood as a whole, but also the media and audiences — continue to participate.

Or as Donaldson noted: “It’s tough to kick down the Academy’s sheen of prestige and being Hollywood kingmakers,” calling the situation a Catch22-. “Participating in a broken system that doesn’t care about you is exhausting and demoralizing. But a lot of people also don’t want to step outside of that system when their voices of protest are needed more than ever.”

There have been Oscar boycotts on an individual level through the years. Marlon Brando in 1973. And Will Smith in 2016.

But imagine if enough Hollywood players with clout and status refused to attend? What if a substantial group publicly rejected the Oscars the way the Oscars have long rejected marginalized communities? It might be the most powerful way to push for meaningful change.

A Weekly Political News Magazine

Issue 1785- January- 31/01/2020

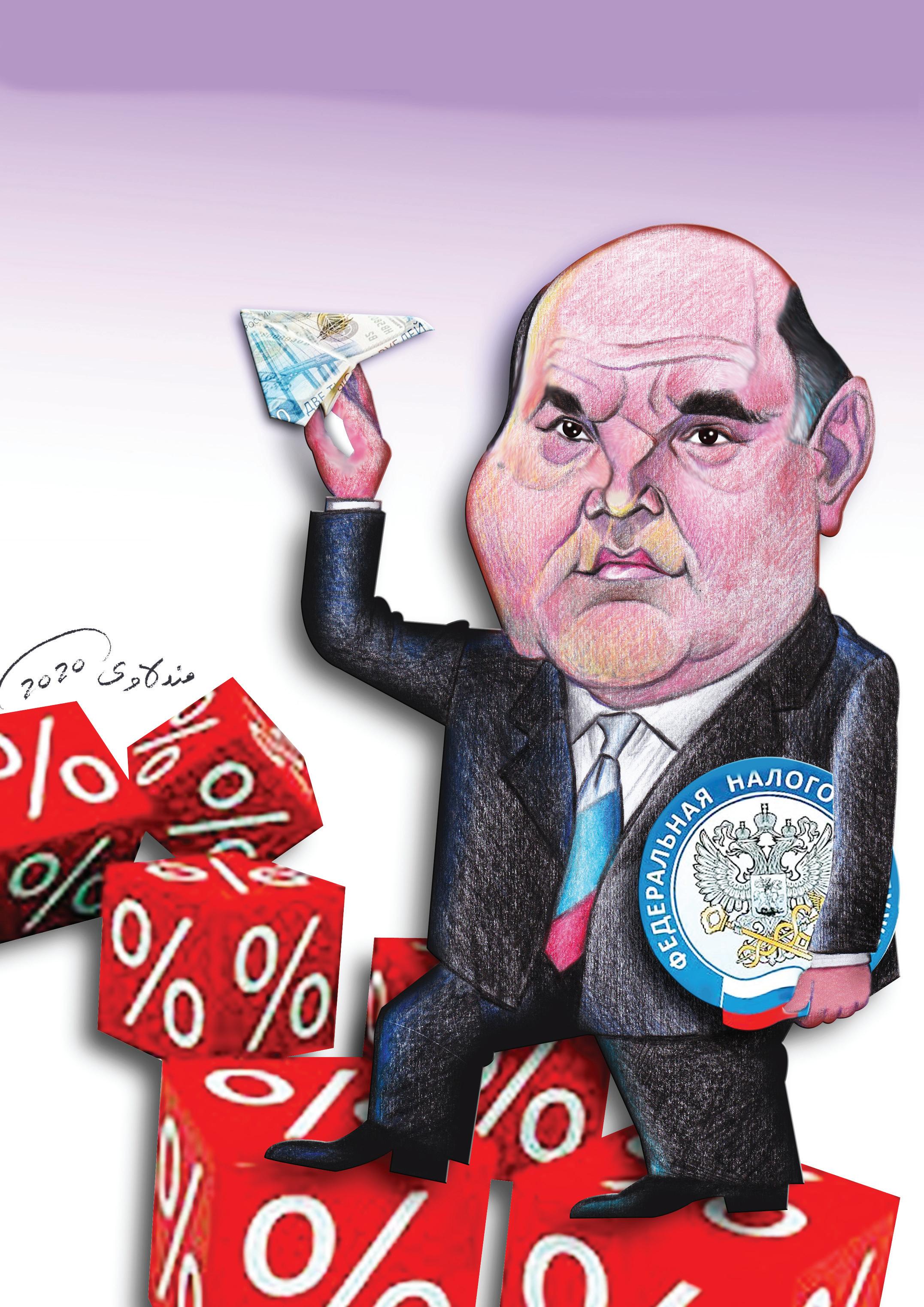

Mikhail Mishustin: From Little-Known Tax Chief to the Second Most Powerful Politician in Russia