Courtyard Houses of India

Yatin Pandya

Yatin Pandya

Yatin Pandya

Yatin Pandya

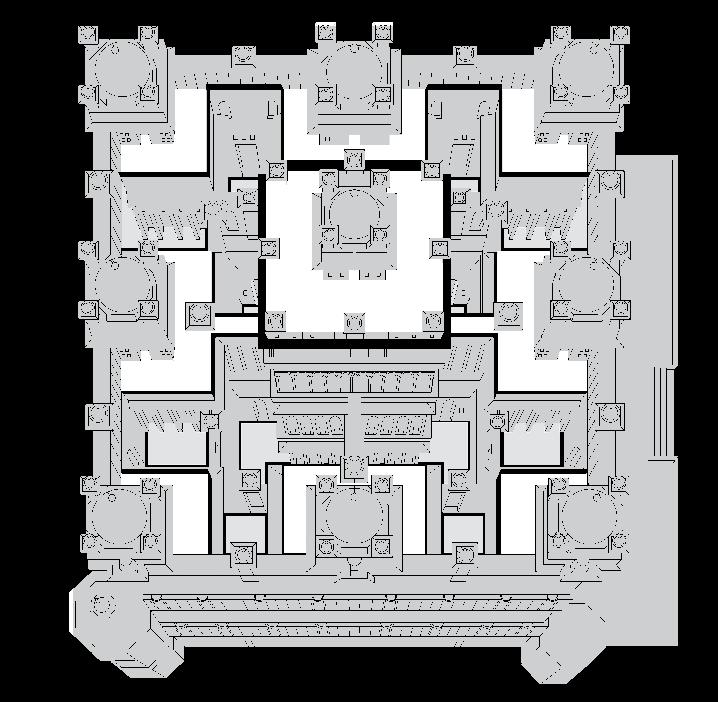

Indian architecture is not an object in space; it integrates space within the object, where the built and the unbuilt become counterpoints to vitalize each other. The alchemy of the two sustains the space and the life within. The void within the built—the courtyard—lies at the genesis of the urban dwelling form in India across geography and time. In ancient Indian sciences, the courtyard assumes the central position as Brahmasthana, the nucleus of the living environment. It provided for an open-to-sky outdoor space while being away from the public eye and thus suited an introverted lifestyle. In this book, the author traces the metaphysical, mythical, socio-cultural, environmental and spatial roles of the courtyard in the domestic architecture of India—from early civilization and Vedic times to Islamic and colonial influences.

This volume documents traditional and vernacular courtyard dwelling types across India within diverse climatic, cultural as well as geographic zones such as western (Gujarat, Rajasthan, Maharashtra), southern (Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, Goa), eastern (Bihar, West Bengal), central (Madhya Pradesh) and northern (Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, Ladakh). It then discerns the spatial elements constituting the court, and the arts, the crafts as well as the elements integral to the court.

Illustrated with splendid photographs and representative drawings, the book attempts to understand the presence and resolution, continued use and adaptation as well as the diverse interpretations and abstractions of the courtyard.

With 352 photographs, 333 drawings and 18 maps

Yatin Pandya

Yatin Pandya

First published in India in 2023 by Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd

706 Kaivanna, Panchvati, Ellisbridge

Ahmedabad 380006 INDIA

T: +91 79 40 228 228 • F: +91 79 40 228 201

E: mapin@mapinpub.com • www.mapinpub.com

© Copyright text, drawings and photographs by Yatin Pandya except those listed under Image Credits on p. 466.

All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher

The moral rights of Yatin Pandya as author of this work are asserted.

ISBN: 978-93-85360-09-1

Copyediting: Roshan Kumar Mogali / Mapin Editorial

Design: Darshit Mori and Gopal Limbad / Mapin Design Studio

Production: Mapin Design Studio

Printed in India

Captions

front cover Art in voids: Courtyard as a thematic experience

back cover Play of colours and ornamentation rendering identity

page 2 Central court at the lower level, Jahangir Mahal, Orchha

page 3 Exploded isometric unfolding built-open interfaces in Datia palace, Madhya Pradesh

page 5 Dynamic rendition of elementary art in the court

pages 6–7 Flooring patterns act as distinguishing elements for different spaces

page 8 Miniature art of Dungarpur palace, Rajasthan, transition through varying spatial narratives

page 13 Intricate wood carving in the courtyard of a haveli in north Gujarat

Medieval Palaces of Madhya Pradesh

Man Mandir Palace, Gwalior

Jahangir Mahal, Orchha

Bir Singh Deo’s Palace, Datia

Nambudiri Illams and Nair Tharavads of Kerala

Olappamanna Illam (Nambudiri house), Palakkad

Anakkara Vadakkath Tharavad (Nair house), Palakkad

Chettiar Mansions of Tamil Nadu

M A M Chettiar’s Palace, Kanadukathan

Traditional Residences of Dakshina Kannada, Karnataka

Chowkimane, Kunjur

Bansaale Mane, Hungaracutta

Saraswat Brahmin Houses of Goa

Gaunekar House, Ponda

Mughal Havelis of Shahjahanabad, Delhi

Haveli at Ballimaran

Haveli Haider Quli, Shahjahanabad

Brahmin Residences of Uttar Pradesh

Two Houses of Brahmnal Mohalla, Varanasi Buddhist

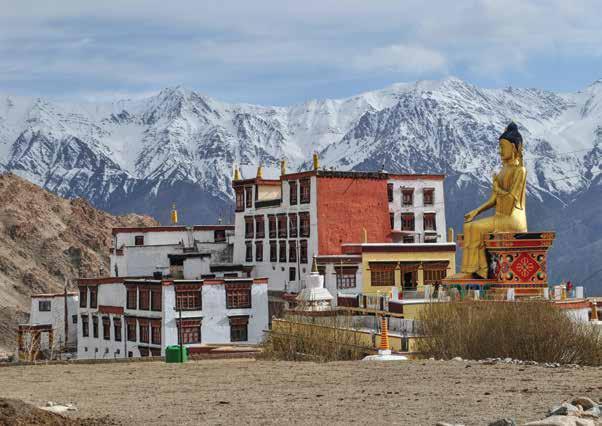

of Leh, Ladakh

in Chennai Haveli at Koteshwar, Ahmedabad

Majmundar Residence, Ahmedabad

Architect’s House, Ahmedabad

Sapre Residence, Kolhapur Shukla Villa, Ahmedabad

House, Ahmedabad

By 2050, two out of three human beings will live in cities. In other words, over the next three decades, 2.5 billion people will be added to the world’s urban population. The rate of urbanization will be particularly dramatic in today’s low- and middle-income countries. Indeed, nearly 90 per cent of the increase in the world’s urban population will be concentrated in Asia and Africa. A combined phenomenon of rapid urbanization coupled with widespread changing demographics brings with it many challenges to people’s livelihoods, to the social ecology of urban communities, to the environment, to the physical and social infrastructure of the world we live in. In the middle- and high-income countries, there are also important societal challenges that should be urgently addressed such as how to keep cities accessible and affordable for all. A key role in all these developments is played by the need for socioculturally appropriate housing.

To make sense of these challenges we face today, we need to develop critical accounts of experiences and developments from the past. Obviously, many large-scale solutions to address the need for housing, focusing only on production speed and numbers, have failed in the past, and are still failing. For the creation of a successful habitat, many more aspects have to be considered in the search for new answers to face the future. We should as well look further back to see and understand how over centuries of time, before the radical modernization of the last century, people created their living and working environment in a slow process of innovation and adaptation of traditions of building and formation of spaces for everyday life.

This book by Yatin Pandya shows us the strength of one of the oldest patterns of habitation—the courtyard house and its ways of clustering. This study makes us acutely aware of how the courtyard house brings together all the elemental functions of a dwelling— protection from climate and hostile environments; the connection of cultural traditions to patterns of everyday life, and finally, the creation of communities.

As the book shows, the courtyard house can, in many different ways, create simultaneously privacy as well as connectivity. It can promote direct connection to others through the possibility of creating dense patterns of shared in-between spaces, both collective and public. This makes the courtyard house also an urban house form par excellence.

The courtyard house was the dominant house type in all early urban cultures—from India to China, from the Middle East to the Mediterranean—and from there exported to the whole world. It is possibly the most powerful architectural definition of space, creating mass to clearly define open space in and outside the dwelling, making privately inhabitable walls to create a communal open centre.

The courtyard house can be considered as a single elementary house form, but it has developed with an amazing and rich variety, always able to react to specific local aspects of domestic and urban life.

This study by Yatin Pandya is an inspiring and very necessary demonstration of the incredible versatility and adaptability of the courtyard house. The book demonstrates how the different climates, cultures and traditions of the regions of India resulted in very distinctive and equally unique courtyard house forms. The book reads as a survey of very scholarly archaeological expedition, carefully documenting the unearthed treasures in series of drawings that together constitute a piece of art by themselves. The drawings vary from diagrammatic interpretations to detailed documentation of the exact physical presence of the case studies. Colourful projections bring plans, sections and elevations together, on the scale of the city and the individual house.

The dense configurations of townhouses with their ornate woodcarved facades in the cities of Gujarat seem much distanced from the extensive, spread-out houses of Kerala, hiding beneath their cantilevering sloping roofs. The analysis shows however that these different appearances are the result of a quest for identity, answered

in very diverse ways on the basis of the particular conditions of climate and culture in each region.

The consistent analysis of the defining aspects of the house form—categorized as environmental management, socio-cultural responses, material elements and manifestation of arts and crafts—make it possible to study in minute detail the climateresponsiveness; adaptability; combination of working and living under one roof; artistic and cultural representation, and careful customization achieved in all the studied examples. The precise answers of the Indian courtyard houses to all these demands can show us the direction that we so desperately need to answer the urgent questions of today.

The responsiveness of the courtyard house seems lost in today’s globalization. The book’s introduction traces how in India’s colonial period the traditional types started to be affected by the introduction of forms and types that were alien to climate and patterns of life. The courtyard has become a space to move around, instead of a space to come together, a place to look at instead of the centre of activity of the community of residents.

The global introduction of Western house forms, both in the colonial period as in the postcolonial world, often as a political tool, failed to acknowledge the climatic and cultural importance and intelligence of the traditional form. The courtyard house, as so clearly demonstrated in Yatin Pandya’s book, should be brought back as the nemesis of the ubiquitous suburban freestanding house, an unfortunate and detrimental import from a very different culture and domestic ideal. One could point here, as just one example of the strength of the courtyard form, to the seminal study of Christopher Alexander and Serge Chermayeff who set out together to find the ideal house form for new residential developments. The conclusion, as given in their book Community and Privacy, published in 1963, was a proposal for a courtyard house, creating

both privacy and a sense of community, showing an amazing parallel to the multiple courtyard havelis of Rajasthan.

Their conclusion was not only based on the spatial layout of the house itself, but also on the possibilities of clustering them. Exactly here lies an essential quality of the courtyard house. It allows for dense urban structures, whilst maintaining privacy and direct connections to the sky and to the ground, to the urban space. The urban courtyard house is never an isolated object, but always part of a larger structure. The densities that can be created in terms of dwellings per hectare can compete with high-rise solutions that too often only result in disconnecting the dwelling from the city and leaving the in-between open spaces undefined and unused.

Access to social housing has been singled out by the United Nations as one of the most pressing social issues, affecting the lives of people all over the world. Solving this challenge is a key element to address the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals and to implement the New Urban Agenda. Architectural and urban design can and should play an important role in this process. We can never address this challenge by isolating the demands for housing from the urgency to create open, accessible cities. This beautiful and thoughtful study of Yatin Pandya challenges us to look beyond the present modes of building cities and dwellings. It opens our eyes to approaches based on a model that has proven over a long period of time its potential to create a dignified human habitat—the courtyard house.

Prof. Dick van Gameren Professor of Housing Design, Chair of the Department of Architecture, Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment, Delft University of Technology, The NetherlandsIndian architecture is not an object in space; instead it integrates space within the object, where the built and the un-built become counterpoints to vitalize each other. The alchemy of the two sustains the space and the life within.

Philosophically speaking, things emerge from nothing and integrate to nothing. This nothing in architecture is the Bindu or Shunya, the void within the built—the courtyard. In ancient Indian sciences, the courtyard assumes the central position as Brahmasthana, the nucleus of the living environment. This engulfed void lies at the genesis of the urban dwelling form in India. Encoded with metaphysical overtones, this spatial element is often exalted to become a spiritual and inseparable aspect of the dwelling.

As a window to the sky, the courtyard is like an umbilical cord between the sky and earth, between indoors and outdoors, and is integral to the dwelling typology across geography and time. Whether it was Indus Valley, Egyptian, Mesopotamian or Chinese, all civilizations were characterized by deep, long houses, compactly packed with three edges shared with the adjoining homes. While this arrangement allowed for the optimization of land and higher densities, it also deprived the inner spaces of light and ventilation. This is why the internal courtyard was adopted as an inherent dimension of the house typology. The courtyard provided for an open-to-sky outdoor space while being away from the public eye. Thus, it suited an introverted lifestyle. Family activity could spill out and yet remain protected from the outside world. Court became an apt, socio-culturally relevant feature as it provided group space for the family, especially women and children, to carry out the daily chores or even festive celebrations. The central void became the connecting volume between floors, as a visual, audio and physical link maintaining rapport between vertically segregated floors.

This research is an exploration to unravel the mythical, sociocultural, environmental and spatial roles of the courtyard in the domestic architecture of India. It traces the evolution of the courtyard from early civilization to Vedic, Islamic and Colonial

periods to understand its presence and resolution, continued use and adaptation as well as the factors shaping the same. It then discerns the spatial elements constituting the court, and the arts, the crafts as well as the accessories integral to the court.

The bulk of the research constitutes documentation of the traditional/vernacular courtyard dwelling types across India. It documents the variations within the diverse climatic, cultural as well as geographic zones of India. Each zone is further investigated for examples conveying the subtle variations and cultural manifestations of the same dwelling typology. The regions covered are western (Gujarat, Rajasthan, Maharashtra), eastern (West Bengal, Bihar), central (Madhya Pradesh), southern (Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Goa) and northern (Delhi, Uttar Pradesh and Ladakh). These dwelling forms have been documented along with the context of their spatial, functional as well as cultural milieus.

These examples have then been compared with respect to their typology, placement, size, profile, predominant elements, accessories and embellishments. A wide spectrum of examples across different periods and regions is drawn to scope out the constants and variables as well as co-relations between spatial, cultural and environmental factors.

This research finally scans some of the contemporary domestic architectural designs to explore the continuation of this element in the present dwellings as well as its diverse interpretations and abstractions. The contemporary examples chosen are not exhaustive but rather representative of the diverse range of interpretations and abstractions. These may be courts as functional introverted spaces, landscaped indoors, light wells, backdrops or organizational seeds.

Ar. Yatin PandyaFootprints E.A.R.T.H. (Environment Architecture Research Technology Housing)

Brahman is life, Brahman is joy, Brahman is the void. Joy, verily, that is the same as the void The void, verily, is the same as joy.

— Chandogya UpanishadThe fundamental nature of this cosmos is space. Its nature is emptiness and because it is empty, it can contain and embrace everything.

— Lama Anagarika Govinda as quoted in The Tao of Physics

Brahman, the formless entity which is the essence of all forms and the source of all life, is often considered to be a void or an emptiness. The void has the potential of containing an infinity of things—the entire universe. It is the one integral reality from which multiplicities emerge, yet it does not suffer any diminution and remains a complete whole. It is characterized as sat (existence), chit (consciousness) and ananda (bliss).

The word Brahman has been derived from the Sanskrit root brh, which means ‘to grow’ and suggests motion, progress and dynamic reality.

Space (akasa) is not a void. Akasa refers to dimensionless space. According to Hindu (Indian) cosmology, it is a subtle element that can be sensorially perceived. In Sanskrit, the word akasa means free or open space, vacuity, or ether, one of the five elements that constitute matter. It has been derived from akasate, which means ‘to appear, to shine, be brilliant’. Akasa would then be that which allows things to appear, be known and, ultimately, exist.

Space is simultaneously the universal container and content. It cannot be categorized as inner or outer space as it is not just that things are in space, but space is also in things. Space is both material and spiritual, man-made as well as divine.

Space can also be conceived as Bindu, a point which acts as the centre of origin, the core of creation where inner and outer forms merge, lose their individual identity and coexist simultaneously. The Bindu is the reference point at which Atman (microcosm) and Brahman (cosmos) connect. Indian philosophy considers the Bindu as the point from where everything emanates and where everything merges. It absorbs and disperses all contradictory energies.

India is divided into different regions with varied topography and climate, vivid socio-cultural beliefs and systems. Each village, city and state forms distinctive responsive environments based on these factors. In this section of the book, we discuss variations in courtyard houses, prevalent traditionally all over India, by splitting the country into five regions—western, eastern, central, southern and northern. In each region, we have selected a few cities in terms of their history and context, and an apt courtyard house as a representative example of domestic courtyards from that city. These examples represent the attributes of the courtyard as a system by itself and its subsystems, such as socio-cultural and economic influences and activities; environmental management through its windows, doors and vegetation; manifestation and expression of art and craft.

Domestic courtyards were found in most civilizations that inhabited India. Apart from its socio-cultural appropriateness, the other influential factor behind the continued presence of the court through the years was its effectiveness in the environmental management of the house. Its central location helped provide ventilation to even the innermost rooms on the ground floor. As a vertical shaft connecting the ground to the sky, it brought cheerful light into these inner rooms—eliminating the need

for artificial lighting during daytime. The height-to-width ratio of the courts was very critical in this regard, and this is one of the main reasons why the scale and proportion of the courtyards varies region-wise to suit the local climate. Religion and the methods used to construct the houses were some of the other factors that led to the variations in these dwelling typologies.

For example, in Gujarat in western India, one would find a range of courtyard houses responding to variable climate conditions— from the urban traditional typology of the pol house (in Ahmedabad) to the small-town mansion at Vaso (Kheda) and the culturally distinct Vohra House (Siddhpur). On the other side, in Rajasthan, as the courtyards had to correspond to the grandeur and scale of havelis and palaces, they were of a larger size and therefore of more height to increase mutual shading. Additionally, in accordance to Rajput customs that give women a special honour and privacy, multiple courtyards for women (zenana) were seen in the havelis. In southern India, as a response to the hot and humid climate, courtyards are longer and less deep, whereas in extreme cold climates such as in North India, courtyards are smaller in size to allow in as little cold as possible.

Based upon Survey of India maps with the permission of the Surveyor General of India. ©2018 Mapin Publishing. Responsibility for the correctness of internal details shown on the main map rests with the publisher.

A miniature painting depicting the urban fabric and built form of Gujarat

A miniature painting depicting the urban fabric and built form of Gujarat

following pages Courtyard as an integral part of the household even in the small town of Uttarsanda, Gujarat

Since Gujarat has the longest coastline in India, it has been blessed with excellent trade. The easy connectivity and accessibility provided the people here—well-known as businessmen and financiers—with good commercial opportunities. With flourishing trade came wealth and a rapidly growing urban lifestyle that brought about a remarkably homogenous and uniform urban pattern over large areas in Gujarat. Therefore, the traditional settlement as well as the dwelling form reflected both the political as well as economic upheavals of the time.

Pre-modern urban settlements in Gujarat were mostly small and compact towns contained within a peripheral wall. Owing to the medieval concerns of political security and also as a response to the hot and dry climate, the town was densely built within the boundaries of the wall. The layout of the town was organic in nature, with a hierarchical pattern of streets. The main roads, secondary streets and bazaars were the major public spaces, whereas open spaces were restricted to small organic squares due to climatic conditions. Narrow streets and lanes acted mainly as connectors.

The neighbourhood formed a cohesive unit and it was interesting that it consisted of people from different yet related occupations. Gender divide was prevalent within the individual houses. Privacy remained important too. In such a scenario, the streets were extensively used for social interaction and gave thermal comfort—making the house form and neighbourhood morphology inseparable from each other. This gave birth to the characteristic settlement structure of Gujarat.

The traditional courtyard form is rendered in a strikingly non-traditional style. Tuscan stone columns with Corinthian-like capitals supporting Gothic arches surround the courtyard on the ground floor. The upper floor walls are punctuated by pilasters, decorated with lime stucco, with Corinthian capitals. The wooden shutters of the first floor windows are panelled and when opened reveal intricate cast-iron railings. The arched portion of the windows is also fitted with intricately patterned cast-iron panels. A careful look at the column capitals reveals the use of Indian motifs in the form of monkeys, lions, etc. In fact, Indian motifs abound but are cleverly integrated in the overall colonial Gothic styling.

The overall style of ornamentation, especially of the street facade, is overtly Gothic, again a preferred colonial style in Pune and Mumbai.

226 Traditional Courtyard Houses of India

226 Traditional Courtyard Houses of India

Overlooking courts and terraces

312 Traditional Courtyard Houses of India

SOUTHERN INDIA

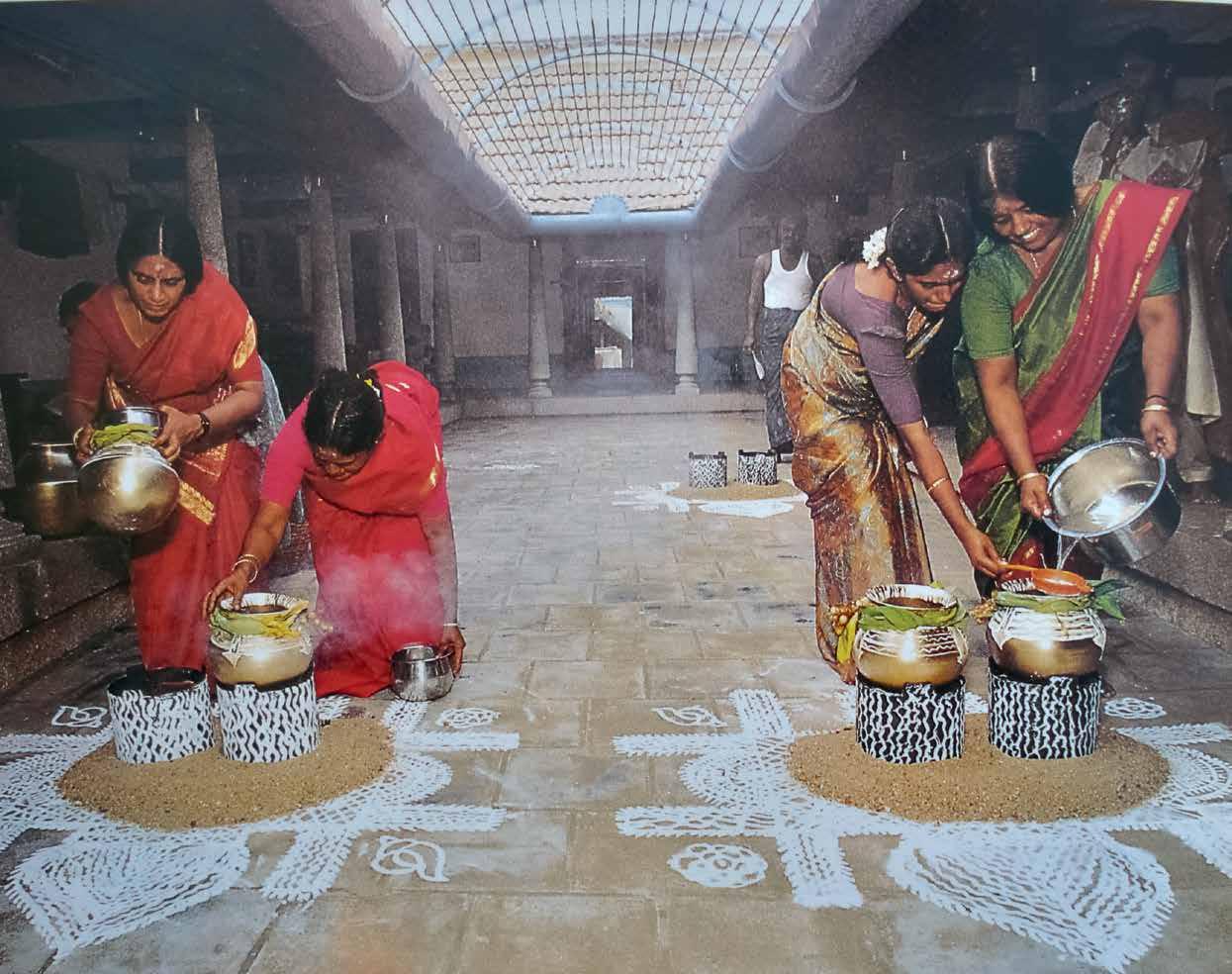

Pongal celebrations in the courtyards

312 Traditional Courtyard Houses of India

SOUTHERN INDIA

Pongal celebrations in the courtyards

During festivals such as Pongal (harvest festival), the courtyards become the primary space of activities associated with the celebration. While the service court (third court) is used for drying paddy, the aisles or pattagasalai (in the second courtyard) are used for chatting and sleeping. During festivities, the muttaram (first courtyard) is used as the celebration space while the aisles are used for seating.

Many of the daily activities related to domestic life are centred around the courts. The service courtyard becomes the space for performing all the tasks connected to cooking since the placement of the kitchen is in alignment to this court. In some houses where the service court is not an elaborate space with a large volume, the second courtyard becomes the space that supports daily chores.

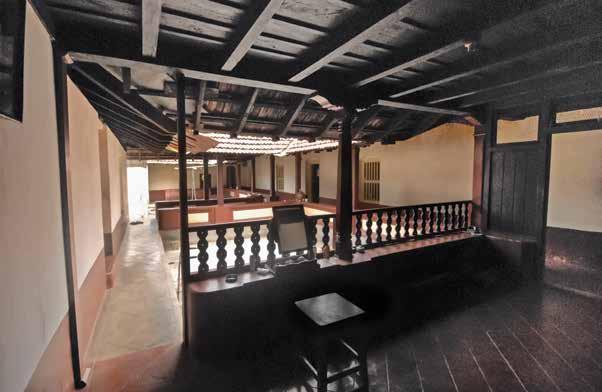

322 Traditional Courtyard Houses of India

Mangalore-tiled old roofscapes of Karnataka

Courtyard as the main axis and system dividing and binding all the spaces

322 Traditional Courtyard Houses of India

Mangalore-tiled old roofscapes of Karnataka

Courtyard as the main axis and system dividing and binding all the spaces

Chowkimane, literally meaning ‘courtyard house’, was constructed by a priest named Ayyappa Narayana in Kunjur in early 19th century. Inspired by the architectural style of Kerala, the house is two-storeyed with steep hipped roof sloping in the central courtyard to withstand the heavy monsoon. The house is made entirely out of timber. This coincides with Thachu Shastra (the science of carpentry), which developed in Kerala and which believes that construction with timber is in harmony with nature, as wood is derived naturally from a living form.

344 Traditional Courtyard Houses of India

View of the central courtyard with a tulsi plant

344 Traditional Courtyard Houses of India

View of the central courtyard with a tulsi plant

on to the aangan (courtyard). The sequence of entry also culminates into the semi-open area around the court which is designated as the actual entry to the house proper. Other rooms are built around the courtyard according to family needs and derive light and ventilation from it.

There is also an enclosed service court where all the cleaning activites take place. This service court is kept accessible from the rear side for domestic workers and servants, whose entry in the forecourt is restricted. There are two wells here, one for washing purposes and the other for cooking and drinking. The formal, sacred and service areas are all located on the ground floor whereas private rooms and multi-functional spaces are on the upper floor. Another traditional feature of the Saraswat house is the balco or the front porch. It is a raised platform supported on two columns that leads to the main door.

This space was used by the Gaunekars to dispense justice and address the people when they had the authority. Now it is used by the family for spending their free time while the forecourt (where the audience would sit) has become a parking space.

The main entrance leads to the aangan through another door and a narrow passage. This passage acted as a buffer area when security was critical. The sequence of entry into the Gaunekar house is very clear—from the open forecourt to the semi-open balco to the enclosed passage and semi-open verandah and finally to the open courtyard—and this emphasizes the importance and sanctity of the centre. There is an inward orientation of spaces, and the level of the courtyard is around 60cm lower than that of the surrounding semi-enclosed areas indicating the transition from enclosed to open, darkness to light or profane to sacred.

The lower storey of the house can be said to be of a more semi-private nature, with guest rooms and living spaces oriented around the courtyard. The kitchen is also in the lower storey.

The puja ghar (worship place) is placed along the way to the family space, thereby signifying the strong presence of god in the daily life of the inhabitants.

The upper storey is in strong contrast to the lower storey. It has a twin set of courtyards. The family space becomes a courtyard, which connects to the three bedrooms on this floor.

The houses present a more modernist outlook in terms of functions, with amenities such as attached toilets and furnished courtyards. The courtyards give a sense of enclosure with height to width ratios approximating 1:2/3. They are also elements of passive cooling and shading in the moderately hot climate of Varanasi. This typology is seen in most of the houses in the Brahmnal area.

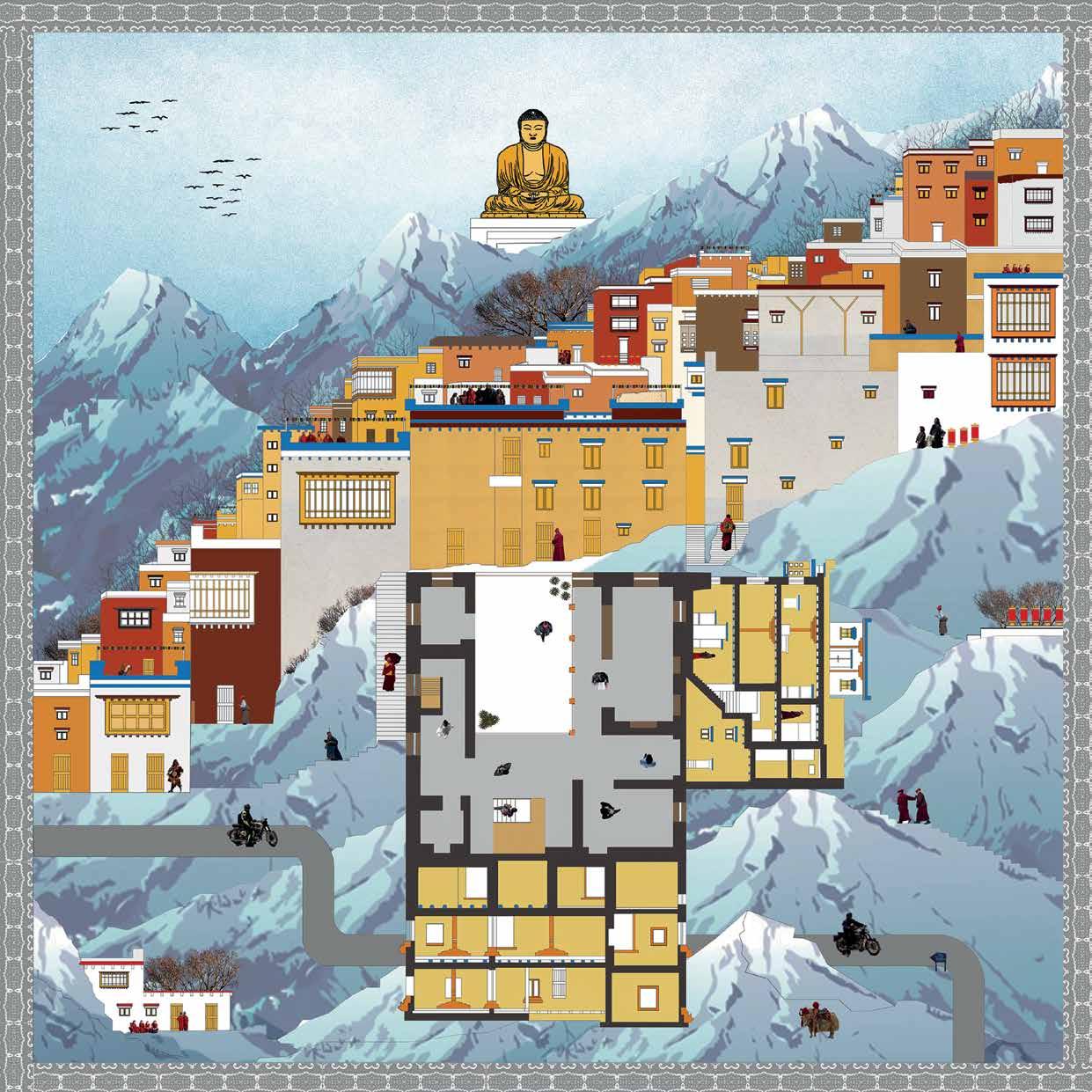

A miniature painting depicting urban fabric and house form of Leh, Ladakh

A miniature painting depicting urban fabric and house form of Leh, Ladakh

following pages An insulated world within: The first layer of protection against the cold exteriors, Lamo House, Leh

Ladakh lies in a high-altitude cold desert, exhibiting the typical elements of such a climate. The climate and occupation are important parameters influencing the design and characteristics of the typical houses in Leh. The traditional dwellings have evolved and adapted the typical courtyard in the form of a terrace at the uppermost floor, which becomes a refuge during the day from the extreme low temperatures.

Yatin Pandya is an author, activist, academician, researcher as well as a practising architect with his firm FOOTPRINTS E.A.R.T.H. (Environment Architecture Research Technology Housing). He is a graduate of CEPT University, Ahmedabad, and holds a Master of Architecture degree from McGill University, Montreal. Pandya has been involved with city planning, urban design, mass housing, architecture, interior design and product design as well as conservation projects. He has authored numerous papers, which have appeared in national and international journals, and has produced several documentary films on architecture. During his tenure at the Vastu-Shilpa Foundation, Pandya worked on the publications Concepts of Space in Traditional Indian Architecture and Elements of Spacemaking, published by Mapin and now in their fourth reprint, which have won the Indian Institute of Architects’ (IIA) Award for Architectural Excellence in Research in the years 2012 and 2014, respectively. The research leading to this book was also carried out during his time at Vastu-Shilpa Foundation. He is a visiting faculty at the National Institute of Design and CEPT University, and a guest lecturer at various universities in India and abroad. The recipient of numerous national and international awards for research, design and dissemination, Pandya counts environmental sustainability, socio-cultural appropriateness, timeless aesthetics and economic affordability to be key principles of his work.

ARCHITECTURE

Courtyard Houses of India

Yatin Pandya

468 pages

352 colour photographs 333 black & white drawings

10 x 10” (254 x 254 mm), hc

978-93-85360-09-1 (Mapin)

₹4500 | $75 | £55

Fall 2022 | World rights

OTHER TITLES OF INTEREST

WOODEN ARCHITECTURE OF KERALA

Miki Desai

auroville architects monograph series PIERO AND GLORIA CICIONESI

Mona Doctor-Pingel

BRINDA SOMAYA

Works and Continuities

Edited by Nandini Somaya Sampat • Curated by Ruturaj Parikh

• with Foreword by James Stewart Polshek