Raja Ravi Varma

PAINTER OF C OLONIAL I NDIA

Rupika Chawla

Raja Ravi Varma

PAINTER OF C OLONIAL I NDIA

Raja Ravi Varma (1848–1906) was among the first Indian painters to successfully adapt academic realism to the visual interpretation of Indian mythology and adopt Western painting techniques of portraiture. His genre of paintings, which eventually led to chromolithographs (oleographs), has maintained a lasting effect on the Indian sensibility, making him the best-known classical painter of modern times.

This book is an account of Ravi Varma’s traditional background and environment in the context of colonial India, and the relationship of this milieu with his profession as an aristocratic itinerant painter. Many royal families of India and several rich and powerful personalities were patrons of Ravi Varma, whose portraits he painted in large numbers.

His range of Puranic and religious paintings, reflecting his deep understanding of Sanskrit and Malayalam literature, have deeply influenced the forms of gods and goddesses in 20th-century visual culture of India. Ravi Varma’s fascination for feminine beauty and the ability to capture it masterfully is abundantly evident in his numerous portrayals of Shakuntala, Sita and Damayanti, and of the Indian woman. His lingering influence on the Indian mindset is also seen in the works of Indian contemporary painters and artists, who continue to be inspired by his art.

This lavishly illustrated book brings together paintings from royal and private collections, and museums. It presents many works that have never been seen before, along with previously undisclosed maps, letters, photographs and other archival material. It traces the sources used by Ravi Varma, examines the techniques and methodology of his paintings, and discusses their conservation and the problem of fakes and copies, much to the advantage of historians, collectors, curators and art aficionados.

With 442 colour illustrations

Front cover

H.H. Sri Chamaraja Wadiyar X, portrait (detail), oil on canvas. See page 106

Back cover

Yashoda Ornamenting Balkrishnan, oil on canvas. See page 236

Raja Ravi Varma

Raja Ravi Varma

PAINTER OF C OLONIAL I NDIA

R UPIKA C HAWLA

Reprinted in 2019, 2017, 2013

First published in India in 2010 by Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd

706 Kaivanna, Panchvati, Ellisbridge, Ahmedabad 380006 INDIA

T: +91 79 40 228228 F: +91 79 40 228201

E: mapin@mapinpub.com www.mapinpub.com

Distributed in North America by Antique Collectors’ Club

E: ussales@accartbooks.com www.accartbooks.com/us

Distributed in the rest of the world by Mapin Publishing

Text © Rupika Chawla

Illustrations © as listed

All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-81-89995-08-9 (Mapin)

LCCN: 2010920300

Designed by Amit Kharsani / Mapin Design Studio

Edited by Diana Romany / Mapin Editorial Processed at Reproscan, Mumbai

Printed in India by Thomson Press (India) Ltd.

A Note to the Reader: Titles of Raja Ravi Varma’s original paintings and sketches appear in bold in the captions. The titles in brackets, where they appear, are the variant names, different from what the painter specified, but those that are more prevalent and often used in museums and publications.

Captions

Page i

H.H. Janaki Subbamma Bai Sahib, Rani of Pudukkottai, and her daughter, oil on canvas, 38.5 x 60.5”, c. 1886. Private collection (See also page 76, for a younger portrait of the Rani painted in 1879)

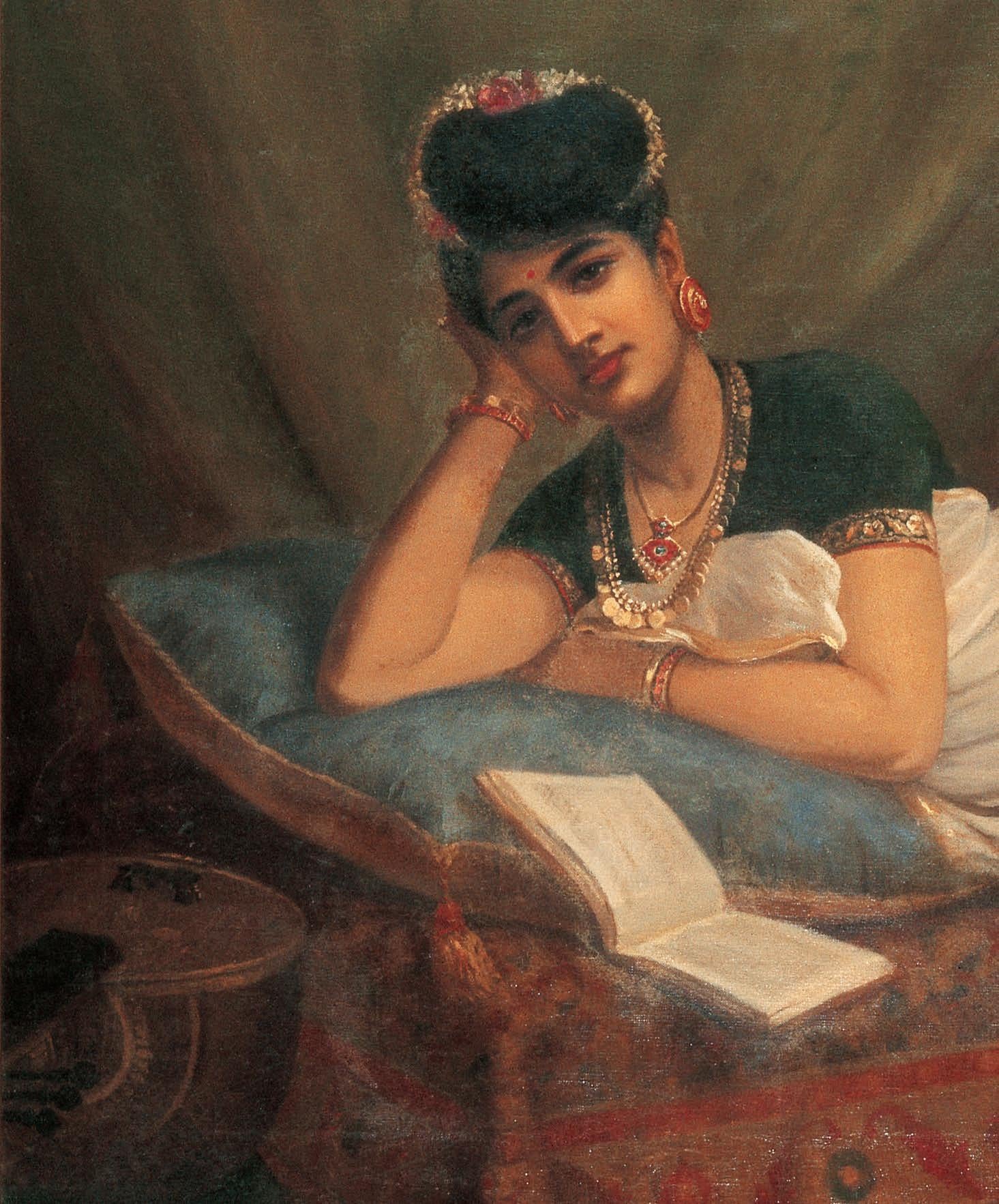

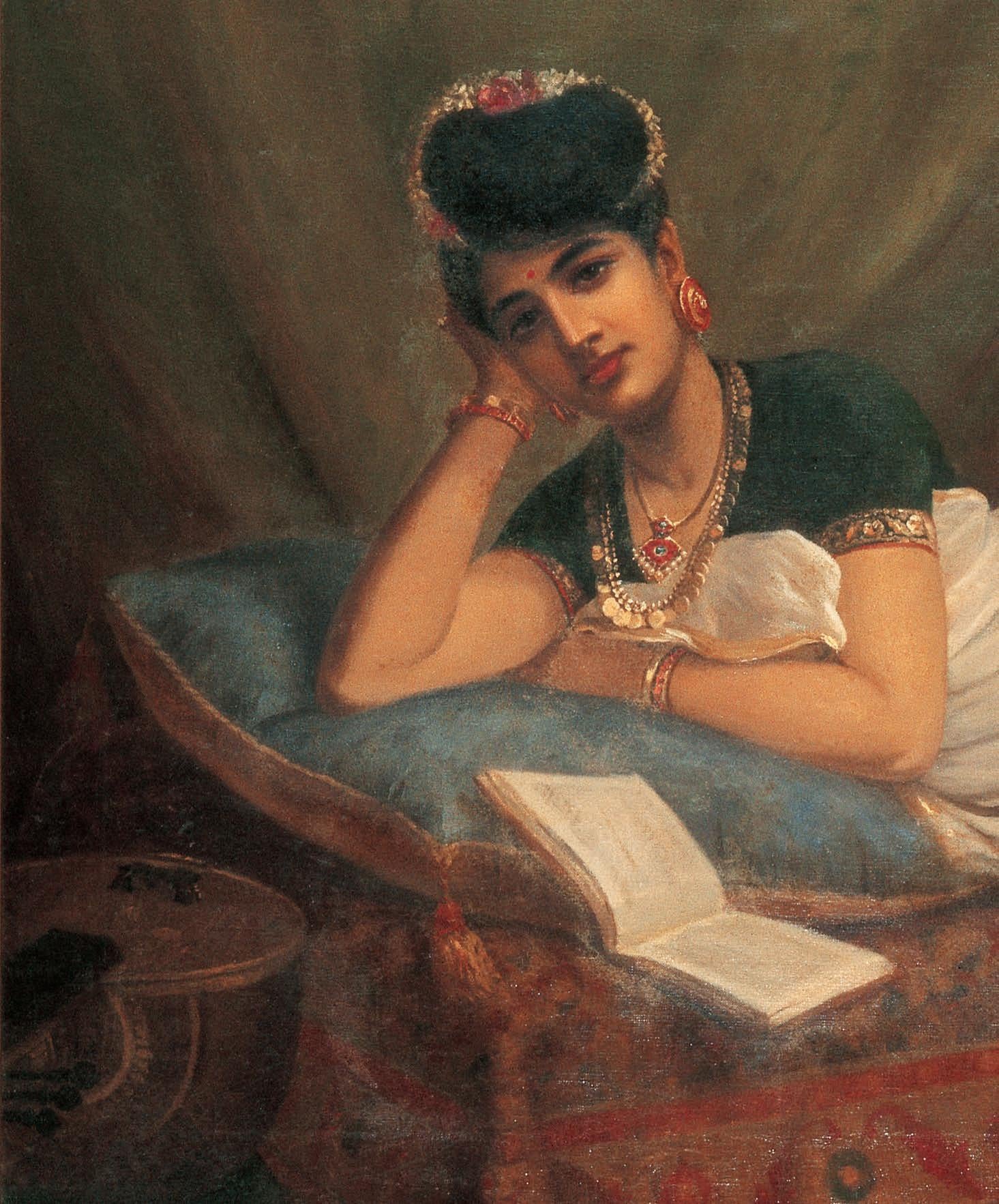

Page ii

Portrait of Indira Bai Moolgavkar, oil on canvas, 29.5 x 40.5”, early 1900s. Private Collection

Ravi Varma used realistic portraits as the starting point for paintings with imaginary subjects. See page 247 for the link between Indira Moolgavkar’s portrait and Kadambari

Page iii

Portrait of Indira Bai Moolgavkar (detail), oil on canvas, 29.5 x 40.5”, early 1900s. Private Collection

Page iv

Bishop Geevarghese Mar Gregorios of Parumala, oil on canvas, 38 x 60”, 1905. Collection: St. John’s Attamangalam Jacobite Syrian Church, Kumarakom, Kottayam, Kerala

“I will varnish the portrait and hand it over to advocate Mr. John in Thiruvananthapuram on the 30th of this month. I have taken extreme care and drawn it beautifully. But on completing the portrait, I have come to feel that this saintly person does indeed possess some divine powers. Because, while drawing this portrait I had started feeling that its size – or something else, was not doing justice to the subject. I would pick up the photo and compare with the portrait and would find no shortcomings or size differences; but the feeling that the portrait was not good enough persisted. I can only say in the end I was made to do one more portrait, larger and more beautiful than the first one. Now there are two pictures that I have been blessed by that divine soul to complete despite my busy schedule: a large picture as commissioned by you and a smaller one that was started earlier and is half-complete.”

Excerpt of letter written by Ravi Varma on completion of the painting, 1905

Page v

Bishop Pulikkoottil Joseph Mar Dionysis II and Mr. E.M. Philip, the Church Trustee, oil on canvas, 58 x 48”, c. early 1900s.

Collection: Syrian Orthodox Old Seminary, Kottayam, Kerala

Pages vi–vii

Rajibai Moolgavkar, watercolour sketch, 11 x 8.5”, early 1900s.

Collection: Dilip Moolgaonkar

Rajibai’s watercolour sketch provided the composition for Disappointing News, see page 82. Another image of Rajibai is on page 101.

Page viii

Radha in the Moonlight, oil on canvas, 57.5 x 41.5”, 1890. Private Collection

Page 1

Yashoda and Krishna (detail), oil on canvas, 28 x 35”. Collection: Travancore Royal Family, Kaudiar Palace, Thiruvananthapuram (See page 166)

Page 2

The Raja and Rani of Kurupam (detail), portrait, oil on canvas, 67.5 x 93.5”, 1902. Private collection (See page 315)

Pages 8–9

Reclining Nair Lady, oil on canvas, 29 x 41”, 1902. Private collection (See page 224)

This book is dedicated to Raja Ravi Varma whose life and works demand that such a book be written.

It is also dedicated to C. Raja Raja Varma, younger brother of Raja Ravi Varma, whose diaries and observations propelled it into the course it has taken.

A drawing of a musician from Ravi Varma's sketchbook

Author’s Note

Overthe years I have often pondered over the enigma of Ravi Varma, the man who painted portraits and mythological paintings, who spawned the beginning of popular visual culture and unbeknown to many Indians past and present, influenced their visual perception down the century. Who was this man who had breathed life into these mythology-based paintings, moved with his times and ahead of them as well, taken a farewell bow in the prime of his life and reluctantly left the sphere of living beings with so much yet to accomplish? He had proved to be both provocative and elusive, yet had beckoned, wanting to be known and discovered. I had to seek him out, pursue his trail and unravel something of this man whose quicksilver thoughts and rich emotional reserves guided his actions and his creativity for fi ftyeight years.

I have not been able to track down every source or run every bit of information to the ground; neither do I believe it possible to do so. After a hundred years there is so much that has vanished with time’s merciless sweep and the indifference of unwilling custodians of tangible evidence. Yet, there was much that was retrieved—a fact this book bears testimony to.

I followed Ravi Varma’s fading footsteps, discovered his environment and family, heard anecdotes, unearthed his friends and their present families, exhumed period letters, newspapers and photographs, and correlated him with the India of his times. Slowly I found him as he emerged from the mists of nothingness, conjured up

The Swan Messenger (detail), oil on canvas, 26 x 73.6”, 1906.

Collection: Srikanta Datta Narasimharaja Wadiyar, Chairman, Sri Jayachamarajendra Art Gallery Trust, Jaganmohan Palace, Mysore

through the information I had gathered and through my reflections that willed him into manifestation. I will never fully know him but I found much to admire in this bright-eyed charismatic man of easy laughter, so capable of balancing the traditional with the avantgarde, gifted with well-honed senses and sensibility, energetic, enterprising and entrepreneurial, a man indeed, of the twenty-fi rst century.

Sources in Mysore and Bangalore

It was a rainy September in 2003, and as usual, Mysore was overflowing with people who had converged for the Dasara celebrations. They were crowded into the palace gardens, lit up by the lights that chased the contours of this vast structure, impervious to the rain that fell well into the night. Central to the festivities was Srikanta Datta Narasimharaja Wadiyar, the erstwhile Maharaja of Mysore, resplendent in his regalia. With everybody preoccupied with the celebrations this was perhaps the wrong time to be in Mysore but Sunny, who photographed a large part of the paintings for the book, was emigrating to Australia. It was vital that he photograph the fabulous Mysore collection before he left, leaving the remainder to his assistant Pratap to finish.

In the midst of his multiple preoccupations essential for this time of the year, the former maharaja, Mr. Wadiyar, most graciously opened up his private rooms for us to photograph his personal collection. Among them was the impressive portrait of Maharaja Chamarajendra Wadiyar, that forms the cover of this book. Large parts of the palace lay in darkness as the electricity had been diverted to illuminate the extensive exterior. With the rain and the darkness, the walk through

the vast areas was almost an adventure. We loped over electric wires temporarily fixed on the roof and hunched under umbrellas in order to reach inaccessible parts of the palace, guided by a man with a lantern.

Mr. Wadiyar did manage to speak with me between crowded, hectic moments, and was kind enough to direct M.G. Narasimha, Superintendent of the Jayachamarajendra Art Gallery, to steer us through our visit, which also included the Mysore Archives located in the palace complex. The archival fi ndings from the Department of Archaeology were rich in information, Museum and Heritage, where I was assisted by the very capable Dr. J.V. Gayathri, the Deputy Director. I am grateful to Kamal Kumar for introducing me to Mr. Wadiyar.

We would not have found a room during this busy festival season but for the sanctuary offered to my daughter Rukmini, who was accompanying me on this trip, our photographer Sunny and me, by the Lalitha Mahal Palace Hotel, thanks to Amitabh Kant, Chairman and Managing Director of ITDC at that time.

Anjolie Ela Menon’s sister-in-law, the late Lily Parameshwar who lived in Bangalore, introduced me to V. Damodaran Nair, who translated from Malayalam the obituary of Ravi Varma, unearthed from the archives of Malayala Manorama by Philip Mathew, the Managing Editor.

Lily Parameshwar also introduced me to the Bangalore based Rukmini Varma, who was of great importance for my research. While at Rukmini’s house I met her sister Lakshmi Raghunathan, author of the book on her grandmother that I consulted often while writing my own. They are both granddaughters of Setu Lakshmi Bayi, one of Ravi Varma’s two granddaughters who were adopted into the Travancore royal family (See Chapter 1). What I should have calculated earlier struck me forcibly now: four to five generations divide us today from Ravi Varma and his contemporaries. This is a detail that I kept well in mind as the research proceeded and as I looked around for lost material. The charming and very informative Rukmini helped further my research by introducing me to Dr. R.P. Raja and Dr. R.K. Varma, other descendants of Ravi Varma’s children who lived in Thiruvananthapuram and in Kilimanur.

In

Kerala

Kilimanur, Ravi Varma’s ancestral home and the place where he died, caught the tangential light of limpid gold as the sun dipped behind the trees. I walked through his palace with Principal R.K. Varma of the Raja Ravi Varma Central School in Kilimanur. Ravi Varma’s studio, which was his sanctuary, now appeared to be a demystified space—just four walls and a large room. Books from his library are locked in a cupboard in another part of the building, with Dr. R.K. Varma as their custodian. Most of them are stamped with Ravi Varma’s insignia, and offer an insight into the kind of books he enjoyed and where he bought them.

The person to give me the correct perspective on Ravi Varma, his milieu and the norms that governed it, was the knowledgeable Dr. R.P. Raja, Ravi Varma’s greatgrandson who lives in Thiruvananthapuram. Without Dr. Raja’s help I would perhaps not have understood the complexities of Ravi Varma’s environment; so essential for a book of this nature.

I am much obliged to the late Maharani Karthika Thirunal Lakshmi Bayi of Travancore, her brother, the erstwhile Maharaja Sri Padmanabha Martanda Varma, (great-grandchildren of Ravi Varma) and Karthika Thirunal Lakshmi Bayi’s daughters, Princess Gouri Parvathi Bayi and Princess Gouri Lakshmi Bayi, of the erstwhile Travancore royal family, for allowing me to photograph their formidable collection. (It was Rukmini Varma who related to me, while in Bangalore, the anecdote about the brocaded fabric gifted to Ravi Varma by the Maharaja of Mysore, later made into the wedding skirt for Rukmini’s grandmother; and it was Gouri Parvathi Bayi who showed me the wedding photograph reproduced in Chapter 1. I am thankful to Hormese Tarakkan, the former DGP of Kerala, and K. Jayakumar, (IAS) for introducing me to Gouri Parvathi Bayi and for making it possible to meet the family at Kaudiar Palace.

While at Thiruvananthapuram, I photographed the extensive Sri Chitra Art Gallery collection with the permission of T. Balakrishnan, who was then Secretary, Tourism and Culture, and C.S. Yalakki, Chief Conservator of Forests and Director of the art gallery in 2003. Mr. Balakrishnan also gave me permission to photograph

KABUL

SRINAGAR PESHAWAR

Lahore Amritsar Simla Ambala Patiala Saharanpur Meerut Multan Bahawalpur

Bikaner Jodhpur

Alwar

Delhi JAIPUR Ajmer Bundi Tonk

Muttra Agra

Rampur Aligarh

Gorakhpur

LACCADIVE ISLANDS

KATMANDU Punakha

Ahmadabad Udaipur INDORE

Bhopal

Baroda Surat Bhavnagar

Nova Goa

BOMBAY Poona

Lucknow Cawnpore

Benares Gwalior

ALLAHABAD Barelly

Mirzapur Rewah

Darbhanga

Patna Gaya Bhagalpur

Kolhapur

NAGPUR Amraoti

Shillong

Sholapur

Mangalore Hubli MYSORE Bangalore Bellary

Calicut Coorg

Cochin

HYDERABAD

Madura Coimbatore Trinnevelly

Trivandrum

Cuttack Jabbulpore

Howrah

MADRAS

Pondicherry (Fr)

Negapatam Tanjore Cuddalore Salem Trichinopoly

Political Map of British India contemporaneous with Ravi Varma’s time, till 1947 The India of that period was divided between what was British India [orange] and princely states [green]. Hyderabad, Mysore, Baroda, Udaipur, Pudukkottai, and Travancore were incorporated into the Indian Union. Bombay acquired the nomenclature of Mumbai, Madras of Chennai and Baroda of Vadodara.

ANDAMAN ISLANDS

MERGUI

ARCHIPLAGO

NICOBAR ISLANDS

some paintings at the Tripunithura Palace in Kochi (Cochin). S. Raimon, who was the Director of the Kerala State Archives, helped me locate a cache of Ravi Varma correspondence, which placed several incidents in perspective and which became the backbone of the sub-chapter on Travancore (See Chapter 3). I thank them all.

In Hyderabad

There is no connection between the crowded Chudder Ghat in Hyderabad today and its more spacious environs of a century ago. I was trying to locate the haveli built by Raja Bhagwan Das, court jeweller to Mahbub Ali Khan Asaf Jah VI, Nizam of Hyderabad. Ravi Varma had moved in with Bhagwan Das after his misunderstanding with the celebrated photographer Raja Deen Dayal, during his unsuccessful visit to Hyderabad in 1902 (described in Chapter 3). I had no precise address for Bhagwan Das’s house but finding it was meant to be, and so I did find it, squeezed tightly into a narrow street and not visible from the busy main road. Miraculous still, as though awaiting my arrival, was a middle-aged gentleman leaning against the gate, who happened to be Gopaldas Bhagwandas Shah, the great-great-grandson of Raja Bhagwan Das, and who welcomed me into the haveli. This connection led to the discovery of the Nizam’s portrait and a set of letters exchanged between Ravi Varma and Raja Bhagwan Das, presently in the possession of Satish G. Shah, the uncle of Gopaldas Shah. The letters helped me develop the narrative about the discovery of the Nizam’s portrait made during the Varmas‘ stay in Hyderabad. My many thanks to Satish Shah, Gopaldas Shah, to Mohamed Safiullah, a collector of old photographs with special interest in those of Deen Dayal, and to our friend S. Anwar, (IAS), who facilitated the transparencies at the Salar Jung Museum and who clarified some details in the text.

In

Tamil Nadu

It seems almost ordained that my many trips to Tamil Nadu made since 1979 which had resulted in my travelling and meeting people in this state, should abundantly come to my assistance when I started the

narrative of this book. Rani Rema Devi Tondaiman and Vijendra Tondaiman of Pudukkottai opened up Ravi Varma’s Pudukkottai, while over our many trips to the Chettinad area I slowly discovered the many ways Ravi Varma’s oleographs had influenced this part of Tamil Nadu, highlighted in Chapter 6. It seemed almost natural for me to chance upon the sculptures at a Trichy temple inspired, yet again, by Ravi Varma’s oleographs. Similarly, a drive to the Courtallam Falls in the company of Mahita and Suresh Jaganathan years before I had even thought of the book had, unknown to me, helped me later invoke the famous waters which Ravi Varma sadly enough had thought would heal his diabetes. There is a whiff of poignancy in his faith in the Courtallam Falls during the last few months before his death as narrated in Chapter 7.

A long interchange with historian and writer S. Muthiah led to the discovery of George Moore’s portrait in the Ripon Building and that of Lord Ampthill’s portrait at the Freemasons Lodge, both in Chennai. Ravi Menon, the present Grand Master, connected me further with Rustom Dastur, ‘Dusty’, and grandson of Aloo Kharegate who is the subject of Ravi Varma’s Going Out. Dusty evoked his grandmother’s personality and unravelled the story behind the portrait, for which I am exceedingly thankful. I acknowledge my debt to N. Ram, the Editorin-Chief of The Hindu newspaper and its meticulously maintained archives, and for Ravi Varma’s obituaries; to Meenakshi Meyyappa, Mahitha Suresh, Sheila Priya (IAS), and Mr. and Mrs. K.K. Varma.

I am indebted to Dr. R. Kannan for being able to photograph the Ravi Varma paintings at the Government Museum, Chennai and for being able to examine and photograph the portrait of W.A. Porter hanging high inside Porter Town Hall in Kumbakonam. It was covered with cobwebs and the painter’s identity had long since lapsed into the past. Porter had been a man of some consequence who had helped to further Ravi Varma’s career in Mysore. While in Kumbakonam I sought out J. Jaishankar, descendant of Seshaiah Sastri, the Dewan of Pudukkottai and friend of Ravi Varma, who informed me that I had come too late as his ancestor’s palace had only recently been pulled down.

In Mumbai and Pune

The Mumbai to Pune stretch proved to be the matrix for several concepts and areas of information that fitted into the general jigsaw puzzle of the book. As in Tamil Nadu, each trip here was never a disappointment; so provocative were the findings in these places. `Bombay’ had to be seen de nouveau through Ravi Varma’s eyes, mainly the geography of the Girgaum/Opera House area frequented by him because of the press and because of the voice of Anjanibai Malpekar, a well known exponent of the Bhendi Bazaar Gharana in Bombay, who lived in this area. I recall with appreciation the many conversations with Suhasini Koratkar, whom I met through S. Kalidas. Suhasini is one of Anjanibai’s disciples who introduced me to Malpekar’s grandchildren Vijay, Sadhana, Vidya and Deepak Ved. They gave me the Hindi translation of the last interview given by Malpekar to a Marathi magazine in 1972, aged 89. It has been reproduced with all its nostalgia in the section on Bombay in Chapter 3.

In Pune, it was from Dr. S.D. Gokhale that I heard of Anand Madgulkar, who knew about the Marathi autobiography of Balasaheb, the Raja of Aundh, a friend and admirer of Ravi Varma, who wrote extensively on the artist in his book. Anand Madgulkar went through the autobiography and sent me the relevant pages that pertained to Ravi Varma, for which I am very grateful. Anjali Nargolkar, introduced to me by D.N. Mishra, my yoga instructor, graciously translated the text for me. I thank them all as the extracts proved invaluable, allowing me an extraordinary insight into Ravi Varma’s art practices, discussed extensively in Chapter 8. Also translated by Anjali Nargolkar were excerpts from the Marathi newspaper, Kesari, with contemporary references to Ravi Varma. Rajender Thakurdesai, who has a special interest in Ravi Varma, researched these at the Pune Archives. He also investigated into the rumoured defamation suit against Ravi Varma by delving through legal gazetteers of the Pune High Court without finding anything sensational. I greatly appreciate the generosity of The National Film Institute with its great archives at Pune; and for allowing me to see how the Magic Lantern operates. The relevant visuals from the National Film Institute archives have truly enriched Chapter 6.

The railway line that connects Pune and Mumbai goes past Malavli, the station for Ravi Varma’s Fine Art Lithograph Press. Fritz Schleicher, who bought the press from the brothers in 1903, lived there till his death in 1935. I thank Patrick Bowring for introducing me to Robert Phillips Sandhu, Schleicher’s grandson. Robert provided me with a perspective to Malavli during Ravi Varma’s time that made the narrative quicken with authenticity. The day spent in Schleicher’s cottage in Malavli’s forest with Robert and his late wife Lisbeth was quite unforgettable.

In Manipal

I started to accumulate the material on Ravi Varma’s press when I met Vijaynath Shenoy, the TrusteeSecretary of the Hasta Shilpa Trust in Manipal, again introduced to me by Anjolie Ela Menon. It was only a couple of years later that I was able to meet with Robert Sandhu, Fritz Schleicher’s grandson. All the surviving lithostones, pigments and oleographs of the press were handed over to Shenoy by Sandhu some years ago and are now displayed in a museum at the Hasta Shilpa Trust in Manipal. It is because of Shenoy’s cooperation that a great deal of this material has been used in Chapter 6.

In Vadodara and Ahmedabad

My special thanks to B.N. Doshi who accompanied me into the Girgaum district of Mumbai, where I evoked the time when Ravi Varma had stayed there. He was equally a great help in Vadodara and Ahmedabad for the days that I was there. I cannot forget G.V. Shah, Superintendent at the Archives in Vadodara and his staff, who were very cooperative. I thank the Sarabhai Foundation and Gira Sarabhai for completing the reference on Ambalal Sarabhai, her father. I am grateful to her sister, Gita Mayor for her insights on Anjanibai Malpekar, and to the painter Amit Ambalal for introducing me to Gita Mayor.

In Udaipur

Ravi Varma and Raja Raja Varma saw the beauty of Lake Pichola from Amet Haveli that stands on the opposite side of the lake from Udaipur’s famous palaces. I was at Amet Haveli with my daughter Rukmini, under a

luminous sky and a soft drizzle standing in the chatri that hangs over the water, the same chatri from where Ravi Varma painted the extraordinary view. My many thanks to the erstwhile Maharana Shriji Arvind Singh Mewar for the photography of his paintings, and to Nina Singh for introducing me to him, as well as to the family at Amet Haveli for allowing me to spend time there.

Museums and Archives

I am indebted to the following museums and archives for enhancing the diversity of visuals in the book: Hill Palace, Thripunithura, Kochi; Madhavan Nayar Foundation, Kochi; Krishna Menon Museum, Kozhikode; Sri Chitra Art Gallery, Thiruvananthapuram; Kerala State Archives; Jayachamarajendra Art Gallery, Mysore; Mysore State Archives; Government Museum, Egmore, Chennai; Fort Museum, Chennai; Salar Jung Museum, Hyderabad; Victoria Memorial Hall, Kolkata; Birla Academy of Art and Culture, Kolkata; National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi; National Railway Museum, New Delhi; National Museum Laboratory, New Delhi; Pudukkottai Museum; Directorate of Archaeology and Museums in Mumbai for the Ravi Varma images at Shree Bhavani Museum, Aundh; Bombay Art Society, Mumbai; Merchant Ivory Productions, Mumbai; Maharaja Fatesingh Museum Trust, Vadodara; Gujarat State Archives, Vadodara; National Archives, New Delhi and the Director General, Mr. S.M. Baqar, and Dr. Gautam there.

In Delhi and elsewhere

The strangers, family and friends who have helped me through the book, its narrative and the journeys undertaken while writing this book are innumerable. I am grateful to A. Ramachandran, Dr. R.P. Raja, Mala Marwah, Ranesh Ray and Chanda Singh for their invaluable help. I also wish to acknowledge Sudha Gopalakrishnan, K.K. Gupta, Madhu Jain, K. Jayakumar, Ranbir Kaleka, Suhasini Koratkar, M.G. Narasimha, M. Safiullah, Robert Sandhu, Shobha Deepak Singh, and Gayatri Sinha for patiently sifting through the text in

varying degrees; Priya Bhasin and Vidita Singh for their sustained help on the computer. I am equally obliged to Rakesh Aggarwal, Vijay Aggarwal, Ashish Anand, Sharon Apparao, Kishore Babu, Nishajyoti Bahadur, Sonia Bellani, Shobhana Bhartia, Shobha Bhatia, Shaupon Bosu, Suma and the late John Chakola, the late Urmila Chathli, Tunty Chauhan, Sita Chidambaran, Avanish Chopra, Kukie Choudhrie, Atul Dodiya, Urmila Dhongre, Professor Dhumal, Ritu and Alak Gajapati Raju, Manisha Gera Baswani, Namita Gokhale, V. Krishnamoorthi, Seth Vijay Kumar, the late Madhavan Kutty, Adithya Lakshma Rao Jatprole, Ashok Mehta, Rakesh Mohan, Kiran and Shiv Nadar, Ritu and Rajan Nanda, Peter Nagy, Karan Singh Pawar, Mr. Perumal, Jyoti M. Rai, Mariam Ram, Chameli Ramachandran, V. Ramesh, Poonam Bevli Sahi, Rajiv and Roohi Savera, Gyanendra Seth, Dilip Shankar, Kavita and Jasjit Singh, Nina Singh, the late Tejashwar Singh, Ujuala Singh, Siddharta Tagore, Faredum Taraporwala, Shikha Trivedi, Neville Tuli, Sunita Vadehra, Amol Vadehra and Madhu and Chander Verma.

My conservator friend Dr. Clare Finn in London introduced me to Dr. Nick Eastaugh who provided me with two important connections: one with Sally Woodcock, who had worked extensively on the Roberson Archives at the Hamilton Kerr Institute at Cambridge, and the other with Sarah Miller, the UK Education Manager at Winsor & Newton. It is the valuable information they generously made available that gave an extra punch to Chapter 8.

My many thanks are for Navin, my husband and steady-constant, and his reflections on the narrative of the book; to my elder daughter Rukmini for her editorial help since I began writing it, and to my younger daughter Mrinalini for burning CDs late into the night! All of them too, for their concern and constant inquiry.

I am extremely grateful to Pavan Morarka for his support. Without his sponsorship I would not have been able to explore Ravi Varma’s world to the extent that I did.

I am indebted to everyone at Mapin for the meticulous work done in the making of the book.

Oleograph of Shakuntala and Menaka, based on the original by Raja Ravi Varma (See page 193)

Private Lives and the Turn of the Century

Memories of a Rare World Thiruvananthapuram, the capital of Kerala, has always been known by that name except for the time when the British referred to it as Trivandrum. There was no single state but three separate regions—Travancore, Cochin and Malabar—till they were amalgamated in 1956 to form Kerala. Trivandrum, which had earlier been the capital of Travancore, continued to be the capital of Kerala after the merging of the three states. In 1991, the city’s original name, Thiruvananthapuram, was reinstated and Trivandrum, as it was known during Ravi Varma’s time, disappeared into history.

About 40 kilometres out of Thiruvananthapuram is Kilimanur, Raja Ravi Varma’s birthplace, which during his lifetime was a prosperous estate inhabited by about 200 members of the Kilimanur clan (Fig. 1.2). It is today almost desolate, and a bleak, shuttered air hovers over the place. Some family members continue to live in Kilimanur, while most of them have scattered in different directions.

The Kilimanur clan originally descended from the rulers of Beypore (near Kozhikode on the northern coast of Kerala), who, for their valorous defense of

Fig. 1.1 Maharani Lakshmi Bayi (1848–1900), oil on canvas, 41.6 x 53.6”, 1883. Collection: Sri Chitra Art Gallery, Thiruvananthapuram

The older sister of Ravi Varma’s wife, Mahaprabha Thampuratty, Lakshmi Bayi was adopted into the Travancore royal family and became the Senior Rani of Travancore.

the Travancore royal family were rewarded with the large estate of Kilimanur. They were known as the “Koil Thampuran,” which was a great honour, as only the Koil Thampurans were permitted to make endogamous marriages with the Travancore royal family. The prefi x of “Raja” to Ravi Varma’s name does not connote kingship even while it finds a connection with his royal antecedents. It is perhaps more strongly linked with the recognition and acknowledgement he received as a painter, from the British and also the Indian elite. For a socially mobile person like Ravi Varma, it would have been of a greater advantage to adopt the more familiar Raja than the unfamiliar “Koil Thampuran” while outside Travancore. Ravi Varma inscribed Koil Thampuran together with his name on paintings whenever he wished to communicate his status. C. Raja Raja Varma, (Fig. 1.3) Ravi Varma’s younger brother, who chronicled their lives for several years, testifies to the importance of this title when he writes in his diary in 1903: “We—the Koil Thampurans of Kilimanur—went first to settle in Travancore for marriage alliances with the royal family.” His own name, Raja Raja Varma, is a proper noun particular to men in Kerala. The initial “C” has no specific relevance. It was attached to Raja Raja Varma’s name in order to differentiate him from other Raja Raja Varmas in the family.

“Varma” is a caste name of the Kshatriyas, who are the warrior class and second in the four-tier caste system in India. Strict codes of behaviour and a rigid hierarchic system had bound the social structure of this

1.2 View of Kilimanur Palace across the paddy fields, as seen in 2003

Fig. 1.3 C. Raja Raja Varma (1860–1905). Collection: R.P. Raja Ravi Varma’s brother, constant and beloved companion, painting assistant, secretary, and writer of a diary maintained over several years till a while before his death in early 1905.

Raja Ravi Varma

Fig.

Fig. 1.4 Junior Rani Parvathi Bayi (1851–1894), oil on canvas, 29 x 40”, 1894. Collection: Travancore Royal Family, Kaudiar Palace, Thiruvananthapuram

The middle sister among Ravi Varma's wife's sisters, Parvathi Bayi, was adopted into the Travancore royal family and became the Junior Rani.

Fig. 1.5 Bharani Thirunal Mahaprabha Amma Thampuran (c. 1830–1890), oil on canvas, 31 x 48”, c. 1890. Private collection Ravi Varma’s mother-in-law and mother of the two ranis of Travancore.

Fig. 1.6 Pooruruttathi Thirunal Mahaprabha Amma Thampuran (1855–1891), oil on canvas, 21 x 25”, undated. Collection: Travancore Royal Family, Kaudiar Palace, Thiruvananthapuram

Ravi Varma’s wife. Names such as Mahaprabha, Lakshmi, Parvathi, Kerala Varma and Raja Raja Varma were often used within the family, necessitating the prefix of the birth star to a name for easy identification.

particular Kshatriya community into which Ravi Varma was born. This insulated them from the outside world for more reasons than just their geographic isolation, which produced in them a perception uniquely their own.

Mavelikkara, some 80 kilometres north of Kilimanur, was the seat of another important Kshatriya family and the home of Bharani Thirunal Mahaprabha Amma Thampuran, mother of Ravi Varma’s wife Mahaprabha Amma Thampuran (Figs 1.5 and 1.6). Mavelikkara could not have marital alliances with the royal family because the caste structure of the two houses did not permit it. But the Mavelikkara family could, and did, marry into the Kilimanur clan. Mahaprabha’s eldest sister, Lakshmi Bayi (Fig. 1.1), married Kerala Valiya Koil Thampuran, known as Kerala Kalidasa, and Parvathi Bayi (Fig. 1.4), the middle sister married Kerala Varma Kochu Koil Thampuran (after his early death in 1872, she was married to Raja Raja Varma Kochu Koil Thampuran, also from Kilimanur).

Lakshmi Bayi and Parvathi Bayi lived lives quite different from their younger sister, Mahaprabha. Apart from links through marriage, the social structure of aristocratic Travancore at times necessitated the adoption of girls into the Travancore royal family. According to the matrilineal system in Kerala, it is the eldest male member in the royal family who becomes the king. In the likelihood of there being no female members, the Maharaja had to necessarily adopt one or two “sisters” or “nieces”. These girls were adopted from Mavelikkara because the caste structure of the two families allowed it. Such an adoption occurred several times in the royal history of Travancore. Both Lakshmi Bayi and Parvathi Bayi were adopted into the royal family as young girls and were subsequently known as the Senior Rani Lakshmi Bayi and the Junior Rani Parvathi Bayi of Travancore.

A different situation endangered the royal line when Kerala Varma Kochu Koil Thampuran, Parvathi Bayi’s first husband, died early in life leaving her childless. Her remarriage became imperative, as the royal line would otherwise have been at risk. She was wedded to Raja Raja Varma Kochu Koil Thampuran a year later in 1873. But it proved to be of no avail, as Parvathi Bayi

too died young, having given birth to four sons and no daughters, while Lakshmi Bayi, unfortunately, remained childless. This complicated matters further and it became obligatory on the Senior Rani to adopt two of her Mavelikkara grand-nieces, the granddaughters of her sister Mahaprabha and Ravi Varma in 1900.

The former Dewan (Prime Minister) of Travancore, Sir A. Seshaiah Sastri, who had retired in the late 1890s and returned to live in Kumbakonam (formerly in Madras Presidency, now a town in Tamil Nadu), wrote to Lakshmi Bayi in 1896, entreating her to adopt her nieces. She replied with the following sentiment: “I have now devoted my life entirely to the service of God, who may be pleased to vouchsafe to me the satisfaction of seeing many more female issues in my mother’s line eligible for adoption to the Travancore Royal Family. I hope to be spared long enough to bring up two girls to inherit my estate and its appurtenances”.1

The “two girls” in their turn, were to become the Senior Rani Setu Lakshmi Bayi and the Junior Rani Setu Parvathi Bayi when the earlier Rani Lakshmi Bayi died in 1901. Setu Lakshmi Bayi (Fig. 1.7) was Ravi Varma’s older granddaughter and the progeny of Mahaprabha, his eldest daughter, acknowledged as being the beauty of the family. Mahaprabha and her mother were known by the same name, as there was a limited choice of names within the aristocracy, also evident in names like “Lakshmi” “Parvathi” and “Raja Raja Varma”. Several of the women in Ravi Varma’s paintings are modelled on Mahaprabha and she is undoubtedly immortalized in There Comes Papa (Fig. 1.8).

The second granddaughter to be adopted was Setu Parvathi Bayi, child of Bhageerathy Amma Thampuran, Ravi Varma’s second daughter. Sri Chithira Thirunal, the eldest son of Junior Rani Setu Parvathi Bayi and the great-grandson of Ravi Varma, was the Maharaja until his death in 1991. His brother, Marthanda Varma is the nominal ruler today, while his sister, Karthika Thirunal Lakshmi Bayi was the Maharani until her death in June 2008 (Fig. 1.10, also see Chapter 3, Travancore). Uthram Thirunal Lalithamba Bayi, elder daughter of Setu Lakshmi Bayi has succeeded her. The painter Rukmini Varma, and Lakshmi Raghunandan, author of

Fig. 1.7 Photograph of Setu Lakshmi Bayi and Shree Rama Varma Koil Thampuran on their wedding day, Trivandrum, 1906. Collection: Travancore Royal Family, Kaudiar Palace, Thiruvananthapuram

Daughter of Mahaprabha, Ravi Varma’s eldest daughter, Setu Lakshmi Bayi was the Maharani of Travancore from 1924 to 1931. Her wedding pavada, a long brocaded skirt, in deep pink, was made from a brocade fabric gifted to Ravi Varma by the Maharaja of Mysore. The pattern of the skirt was used by Ravi Varma in Sri Krishna as Envoy (Fig. 4.19), a tribute paid to his royal patron.

Fig. 1.8 There Comes Papa, oil on canvas, 32 x 49”, 1893, signed “Ravi Varma, 1893” in black, below left. Collection: Travancore Royal Family, Kaudiar Palace, Thiruvananthapuram

Ravi Varma’s eldest daughter, also called Mahaprabha (1872–1919), with her one-year-old son, Marthanda Varma. Her beauty inspired her father to often adapt her classical features in his paintings. There Comes Papa was one of the 10 paintings sent by Ravi Varma in 1894 to the International Exhibition at Chicago. He was advised to add a dog to the painting with the reason that the dog would be an added attraction for American viewers. Over a century ago, household pets were seldom seen in Indian homes, as they were considered unclean.

At the Turn of the Tide: The Life and Times of Maharani Setu Lakshmi, the Last Queen of Travancore, are her daughters.

The social system of Ravi Varma’s environment was both rigid and complex, governed by many rules that guided the religious and sociocultural life of the community. Much of the complexity hinged on the matrilineal system itself. According to this concept, the Brahmins married into their own community while also forging alliances with Kshatriya women and those of other castes, thus sustaining dominance over other sections of society. The families of Kilimanur and Mavelikkara, as has been explained, were Kshatriya clans.

The Kshatriya wife did not live in her husband’s home for various reasons, a custom that continued till the 1950s. Intercaste marriages were the practice in earlier times. But such a system did not permit a Kshatriya wife to live in the home of her Brahmin husband.2 For this reason women who married Brahmins continued to live in their mother’s home after marriage. Their children grew up in the same house. Thus the matrilineal system continued, extending into large joint families.3

Ravi Varma’s parents, to whom he was born on 29 April 1848, are an example of such a union. His father, Ezhumavil Neelakantan Bhattatiripad was a learned Namboothiri Brahmin, the highest among all Brahmins. The Brahmins were traditionally priests and teachers and above all others in the caste system. His mother, Uma Amba Bai Thampuratty of Kilimanur, was a Kshatriya, intellectually accomplished and an acknowledged Malayali poet. Their four children, Ravi Varma, Goda Varma, Raja Raja Varma and Mangala Bayi, lived in Kilimanur (Figs 1.11 and 1.12), which was their mother’s

Travancore Royal Family, Kaudiar Palace, Thiruvananthapuram

Family members playing the veena were a frequent sight in Ravi Varma’s milieu, resulting in several paintings of this genre.

Fig. 1.10 The Hindu, 29 October 1937. Courtesy: The Hindu Archives, Chennai

Clockwise from top left: Maharaja Sri Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma, son of Junior Rani Setu Parvati Bayi; Ravi Varma's granddaughter Junior Rani Setu Parvati Bayi; her younger son, Marthanda Varma: now the erstwhile Maharaja of Travancore, Sri Padmanabha Dasa; Junior Rani Setu Parvati Bayi's daughter, now the late Maharani Lakshmi Bayi; Maharani Setu Lakshmi Bayi, Ravi Varma's older grandaughter adopted into the Travancore royal family.

Fig. 1.11 View of Ravi Varma’s studio as seen in 2003.

The studio occupies a prominent position in the grounds of Kilimanur Palace. The yellow painted door on the extreme left earlier led to an open verandah where Ravi Varma sat and listened to the recitation of ancient texts.

Fig. 1.12 Ravi Varma in the open verandah outside his studio listening to scriptures, late 19th century. Collection: R.P. Raja.

Fig. 1.9 Veena Player, oil on canvas, 34 x 43”, undated, signed “Ravi Varma” in red, below left. Collection:

Fig. 1.13 Nair Lady Arranging Jasmine in Her Hair, oil on canvas, 18 x 24”, 1903. Collection: Travancore Royal Family, Kaudiar Palace, Thiruvananthapuram

Fig. 1.14 Ramaswamy Naidu, Lady Coiling Jasmine in Her Hair, oil on canvas, 27 x 35”, undated. Collection: Sri Chitra Art Gallery, Thiruvananthapuram

Fig. 1.15 Varasiyar at the Bathing Ghat, oil on canvas, 31.6 x 56”, c. 1890s. Collection: Travancore Royal Family, Kaudiar Palace, Thiruvananthapuram

An anecdote often recounted within Ravi Varma’s family was of a Varasiyar lady who drifted to the wrong bathing tank by mistake. This incident inspired Ravi Varma's depiction of the embarrassed young woman in this painting. The Warriers maintained major temples.

Fig. 1.16 Wife of Kunjaru Raja, oil on canvas, 26 x 34”, 1870. Collection: Salar Jung Museum, Hyderabad

Kunjaru Raja was the head of the Mavelikkara family and a close friend of both, Prince Martanda Varma of Travancore and Ravi Varma. Ravi Varma's wife was from Mavelikkara.

Fig. 1.17 Nair Lady with Mirror, oil on canvas, 28.6 x 40.6”, 1894. Collection: Government Museum, Chennai

This work reflects one of the many familiar sights that structured Ravi Varma's childhood environment.

Fig. 1.18 Goda Varma. Collection: R.P. Raja

Goda Varma was the modest, quiet sibling who led a comparatively uneventful life in Kilimanur managing the affairs of Ravi Varma and Raja Raja Varma while they were away. He was a musician of considerable talent.

161718

“Rupika Chawla’s lavishly produced book is not a heavy academic tome. In style and substance, it is hugely engaging, carrying its scholarship with a remarkable lightness of grace.”

ART

Raja Ravi Varma

PainterofColonialIndia

Rupika Chawla

384 pages, 460 colour illustrations

9.5 x 11.5” (241 x 292 mm), hc

ISBN: 978-81-89995-08-9

₹4500 | $65 | £5490

4th Reprint in 2024 | World Rights

Rupika Chawla is a conservator of paintings based in Delhi. She has restored several Ravi Varma paintings at her studio in Delhi and she also gives training in conservation. Together with artist A. Ramachandran she had organized the seminal exhibition on Raja Ravi Varma in 1993 at the National Museum, New Delhi, which brought about a strong revival of the artist and his work. She has written extensively on contemporary Indian art, and is the author of Surface and Depth: Indian Artists at Work (Viking), A.Ramachandran: Art of the Muralist (Kala Yatra & Sistas) and Icons of the Raw Earth (Kala Yatra). She also maintained a column in The Indian Express from 2001 to 2004.

Other titles of interest

Maharanis

Women of Royal India

Edited by Abhishek Poddar and Nathaniel Gaskell

EBRAHIM ALKAZI

Directing Art

The Making of a Modern Indian Art World

Edited by Dr. Parul Dave-Mukherji

Kalamkari Temple Hangings

Anna L. Dallapiccola

Mapin Publishing www.mapinpub.com

in India

“In this sumptuous feast of a book, one of India’s finest art conservators, Rupika Chawla, takes out all her scholastic implements to bring us a sprawling investigation of the works of 19th century artist Raja Ravi Varma. Chawla locates Ravi Varma in the productive world of salon art shaped by Victorian aesthetics but in the very localised template of India.”

Hindustan Times

“Coming armed with awe-inspiring research and studded with gem-like details, Raja Ravi Varma: Painter of Colonial India is surely a long overdue opus …Rupika Chawla’s lavishly produced book is not a heavy academic tome. In style and substance, it is hugely engaging, carrying its scholarship with a remarkable lightness of grace.”

—S. Kalidas, India Today

“…with this sumptuous, well-researched and deeply written volume, Chawla has performed a much needed art-historical task by restoring the artist himself back into contemporary national consciousness…There is a racy time-line running through the narrative which makes it most accessible to the scholar as well as the layperson.”

—Sadanand

Menon, Outlook ₹3950 / $75 / £50