The Uprising of 1857

Edited by Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Edited by Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Edited by Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

Edited by Rosie Llewellyn-Jones

The ‘sepoy revolt’ was among the first fully photographed wars in the history of documentary photography in India. This volume offers multiple perspectives on the ‘Ghadar’ or Uprising of 1857, and deconstructs the grand narratives associated with colonial historiography. Using rare archival photographs from the Alkazi Collection, together with supplementary visual material, these essays re-evaluate the ‘evidence’ and official reading of the Uprising.

Linked accounts negotiate ‘Mutiny’ landscapes and architecture: the internal dynamic of the rebellion decoded through topography and monuments, including memorials, cemeteries, churches and forts, as well as the sites of appalling atrocity and retribution—besieged barracks, burning villages, gallows at crossroads and looted palaces.

Along with rebels, British troops and their determined generals, and various professional and amateur photographers caught up in documenting the turbulence, the dramatic vista of the Mutiny in these essays is also inhabited by a range of significant characters central to the action, including the warrior queen Lakshmi Bai, the exiled last Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar and the poet Mirza Ghalib.

With 168 illustrations

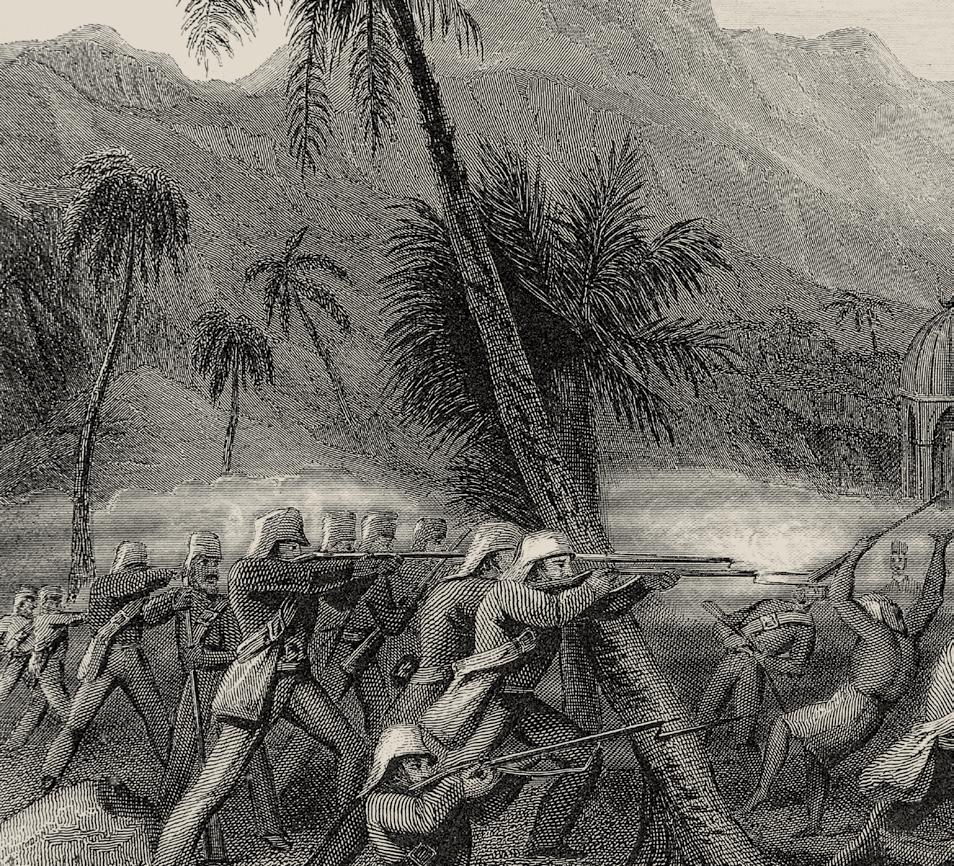

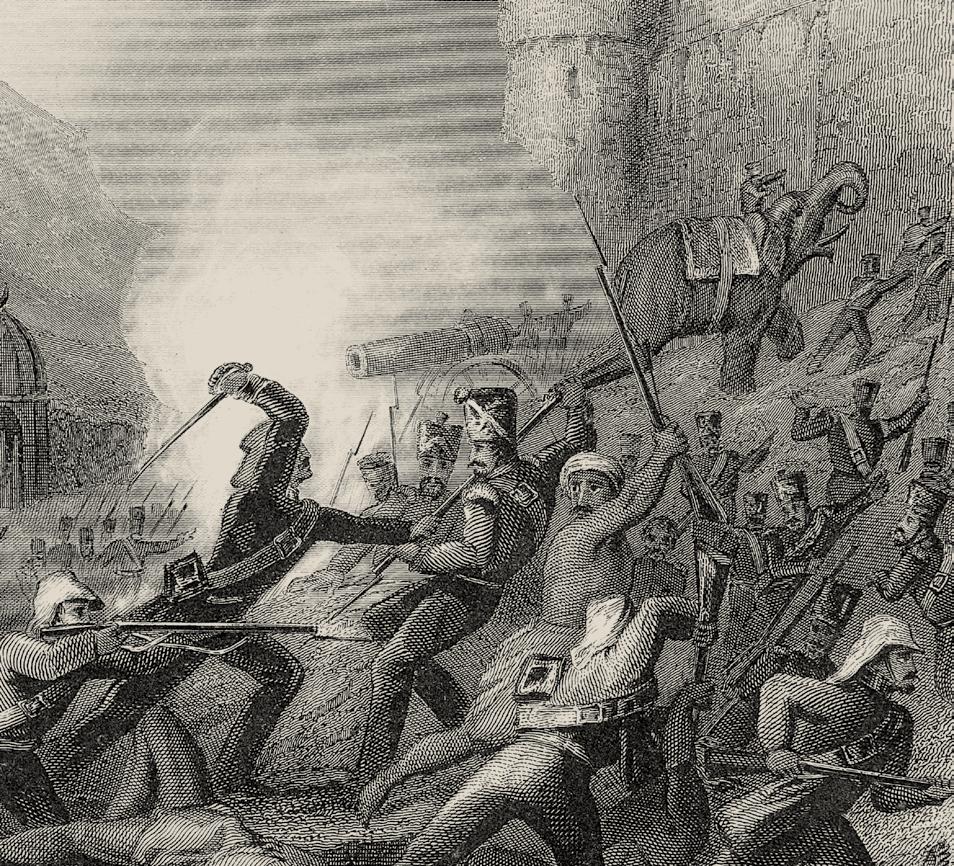

FRONT COVER The London Printing and Publishing Company Limited

‘Capture of a Gun at Banda’ from the book The History of the Indian Mutiny by Charles Ball (detail), 1857 (See p.178)

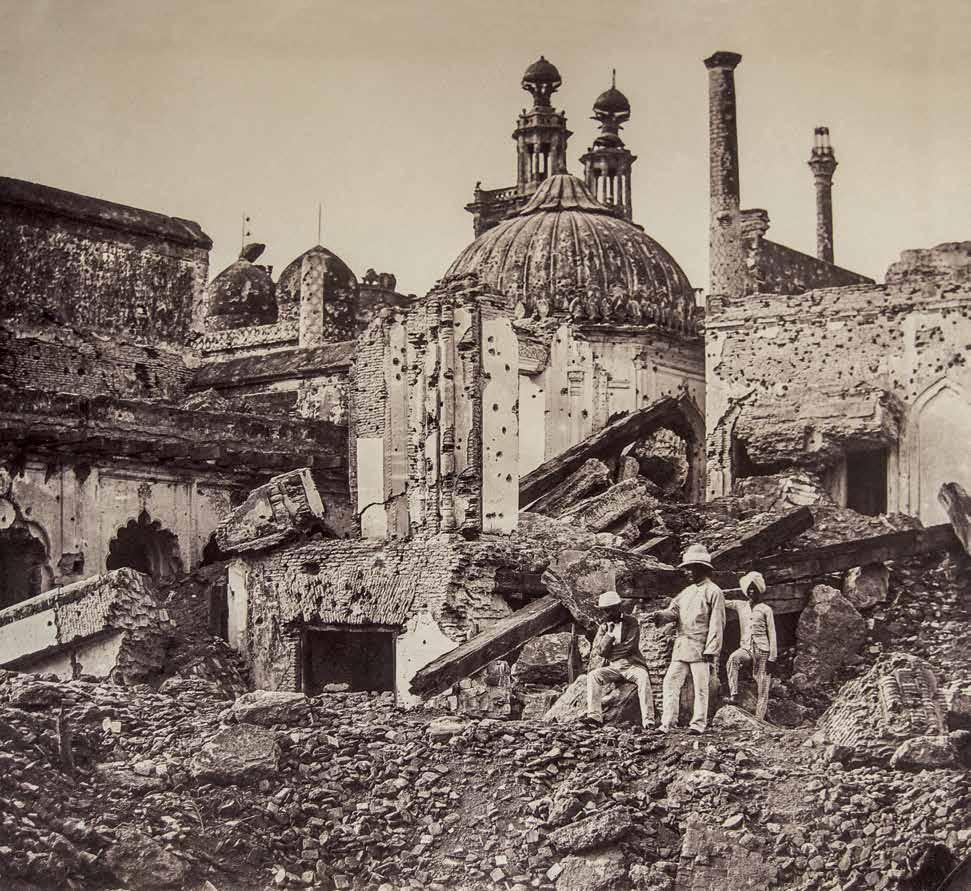

BACK COVER Felice Beato

‘The Mine in the Chutter Manzil, exploded by the Enemy in the first attack of General Havelock’ from the album Views in Lucknow, Cawnpore and Delhi, 1858–1859

Albumen Print, 253 x 296 mm

ACP: 98.77.0001(31)

First published in India in 2017 by Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd

706 Kaivanna, Panchvati, Ellisbridge

Ahmedabad 380006 INDIA

T: +91 79 40 228 228 • F: +91 79 40 228 201

E: mapin@mapinpub.com • www.mapinpub.com

in association with

The Alkazi Collection of Photography, New Delhi rahaab@acparchives.com

in conjunction with the exhibition ‘Illuminating India: Photography 1857–2017’ at the Science Museum, London, October 4, 2017 to March 31, 2018

International Distribution

North America

Antique Collectors’ Club

T: +1 800 252 5231 • F: +1 413 529 0862

E: sales@antiquecc.com • www.accdistribution.com/us

Rest of the World Prestel Publishing Ltd.

14-17 Wells Street

London W1T 3PD

T: +44 (0)20 7323 5004 • F: +44 (0)20 7323 0271

E: sales@prestel-uk.co.uk

Text and Illustrations © The Alkazi Collection of Photography unless noted otherwise, reproduced with permission.

All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

The moral rights of Rosie Llewellyn-Jones, Shahid Amin, Mahmood Farooqui, Nayanjot Lahiri, Andrew Ward, Tapti Roy, Susan Gole, Zahid R. Chaudhary and Stéphanie Roy Bharath to be identified as authors of this work are asserted.

ISBN: 978-93-85360-11-4

Copyediting: Smriti Vohra, Ateendriya Gupta / Mapin Editorial

Editorial coordination: Jennifer Chowdhry, Neha Manke / Mapin Editorial

Design: Gopal Limbad / Mapin Design Studio

Design assistance: Sarayu Narasimhan / Mapin Design Studio

Production: Mapin Design Studio

Printed at Parksons Graphics, Mumbai

CAPTIONS :

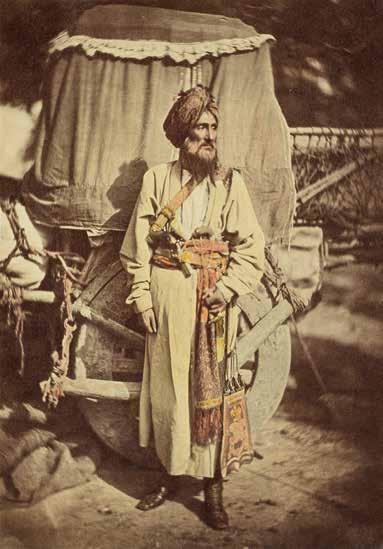

PAGE 1 Felice Beato

‘A Sikh Soldier of Hodson’s Horse, Lucknow’ from an untitled album, 1858–1859

Albumen Print and Watercolour, 194 x 133 mm

ACP: 99.07.0001(04)

PAGES 2–3 Samuel Bourne

The Baillie Guard Gate, Lucknow, 1864–1865

Albumen Print, Photographer’s Ref. 1027, 203 x 288 mm

ACP: D2003.27.0001

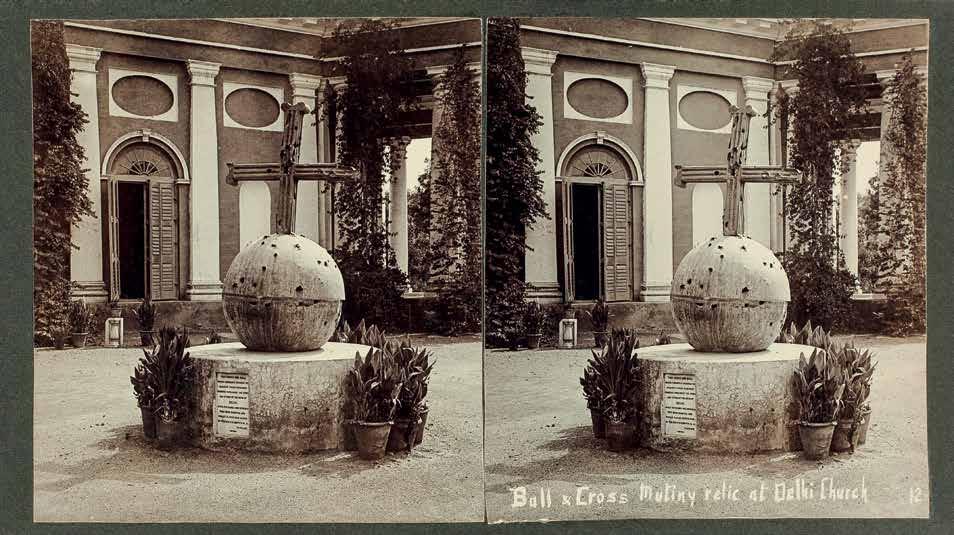

PAGE 6 H. Hands & Son’s

‘Ball & Cross Mutiny Relic at Delhi Church’ [St. James’ Church], c. 1890

Gelatin Silver Prints on Stereo-card, Photographer’s Ref. 12, 81 x 72 mm [each]

ACP: 94.132.0004

There have been several individuals and institutions that have been instrumental in facilitating this publication, many of whom are writers and publishers on the modern history of the Uprising, or the historiography of the 19th century more generally. Some of their contributions are cited by way of an extended reading list at the end of the book as they have also inspired an approach to the past through visual records.

This entire initiative could not have been realised without the sheer dedication and perseverance of its editor, Dr. Rosie Llewellyn-Jones, who spent a colossal amount of personal time and energy on the project right until its production; as well as all the authors with their untiring labour, patience and unconditional support. This project has been many years in the making and it goes without saying that a collective generosity of spirit has enabled its eventual release, at a time that is very apt, both politically and culturally—marked by a commemoration of 70 years of India’s Independence, and the associated UK-India Year of Culture, further supported by the British Council.

To aid the efforts of the contributors, copyeditors Smriti Vohra, earlier at the Alkazi Foundation, and Ateendriya Gupta, from Mapin Publishing, gave this volume further unity and reader-friendliness. I would also like to thank the historians Ms. Narayani Gupta and Mr. Rudrangshu Mukherjee for their initial interest and intellectual pursuits; Squadron Leader Rana Chhina, MBE; and Professor Saleem Kidwai for their invaluable advice.

At the level of production and design, I thank Mapin and its staff, once again, under the tremendous management of Bipin Shah, who worked night and day to realise this book in time.

From Alkazi Foundation for the Arts, my gratitude to the staff, especially Jennifer Chowdhry, Shilpi Goswami, Hitanshi Chopra and Mr. Vijay, who coordinated between the authors and the copublisher, and helped in the proofing of the final copy. As Curator of the Alkazi Foundation, it has been an absolute privilege to share this material as a standing mandate of the private collection of Mr. E. Alkazi, whose enduring commitment to the arts in general is being further consolidated by Mrs. Amal Allana and Mr. Feisal Alkazi, Lifetime Trustees of the Alkazi Foundation.

And finally, I would like to express my appreciation to the Science Museum in London, particularly Ms. Kate Bush and her assistant Ms. Shasti Lowton for hosting the launch of this volume in the context of the photography exhibition, Illuminating India (1857–2017).

Rahaab Allana Curator, Alkazi Foundation for the Arts7th

February

26th

19th Bengal Native Infantry troops at Berhampore refuse to use greased cartridges

March

29th

Mangal Pandey, 34th Bengal Native Infantry, wounds two British officers in a failed mutiny attempt

April

8th

Mangal Pandey hanged at Barrackpore

May

3rd

Sir Henry Lawrence confronts mutinous troops of the 7th Oudh Irregular Infantry at Lucknow. Leaders of the revolt are hanged or imprisoned

6th

34th Bengal Native Infantry disbanded at Barrackpore for striking their British officers

10th

Sepoy s at Meerut mutiny kill British civilians and officers and ride to Delhi

11th

Meerut sepoy s arrive at Delhi, and are joined by the garrison, Europeans murdered or flee

30th

Lucknow garrison mutinies

First ‘Mutiny’ Act XI passed by Legislative Council, Calcutta, makes it an offence to rebel, or conspire to rebel against Queen Victoria or Government of the East India Company

June

6th

General Wheeler and Europeans are besieged at Cawnpore by the local garrison

8th

Battle of Badli-ki-Serai allows British troops to establish their base on the Delhi Ridge

12th

130 Europeans escaping from Fatehgarh murdered at Bithur by Nana Sahib’s men

13th

‘Mutiny’ Act XV attempts to stifle the vernacular and English press

27th

Europeans massacred at Sati Chaura Ghat, Cawnpore, after false promise of safety by Nana Sahib

30th

Sir Henry Lawrence and troops defeated by rebels at Chinhat, and retreat to the Lucknow Residency, where the siege begins

July

15th

Third massacre at Cawnpore, 200 European women and children killed by Nana Sahib’s men

17th

General Havelock enters Cawnpore and finds massacre remains in the Bibighar well

August

13th

Sir Colin Campbell, newly appointed Commander-in-Chief, arrives in Calcutta

September

14th

General Archibald Wilson begins the final assault on Delhi

20th

Delhi recaptured by British and Indian troops

21st

Bahadur Shah Zafar, King of Delhi, captured at Humayun’s tomb by Captain William Hodson

22nd

Three Mughal princes shot by Captain Hodson at Khooni Darwaza, Delhi

25th

First relief of the Lucknow Residency by General Havelock and Sir James Outram

November

17th

Second, successful relief of the Lucknow Residency by Sir Colin Campbell, British withdraw from the city

March

2nd

Sir Colin Campbell begins the recapture of Lucknow

14th

Looting in the Qaisarbagh Palace, Lucknow

16th

Lucknow is finally recaptured after fierce fighting

21st

Government Commission to apprehend rebellious sepoy s established under John Cracroft Wilson at Allahabad

April

3rd

Sir Hugh Rose captures Jhansi

17th

Lord Canning issues printed list of rebel names and descriptions

June

17th

Lakshmi Bai, the Rani of Jhansi, killed by British troops at Kotah-ki-Serai, near Gwalior

November

1st

Proclamation by Queen Victoria read throughout India announcing that the Crown has assumed authority for the country and issues a pardon for all rebels except murderers

By 1857 the East India Company ruled almost half of the Indian subcontinent , acting as the agent for the British government. States outside the Company ’s direct rule had Residents or Political Agents attached to the princely courts. There had been one kingdom left in India, the kingdom of Awadh , until the Company annexed it in 1856 and deposed its ruler, Nawab Wajid Ali Shah. Awadh lay to the east of Delhi , the ancient city that , too, had a king of sorts, Bahadur Shah Zafar, but whose remit now extended no further than the city walls of the old Mughal capital.

The East India Company, or the “Honourable East India Company” and sometimes simply “Company Bahadur ” as it was called by those who sought something from it, arrived in India at the end of 1600. It was only one of several European companies set up in the 16th and 17th centuries to trade with South Asia, but it became the most successful. Having defeated its most serious rival, the French Compagnie des Indes, the English Company expanded rapidly. Territorial gains were made through treaties, through trade, through war, and latterly, as in the case of Awadh, through annexation. Given its success there seemed no reason why the English Company should not gobble up the whole of India. By the 1850s, the Company was buying up land to build railways and install the electric telegraph alongside the railway lines. Christian missionaries, who appeared to have the Company’s blessing, or at least its benevolent interest, had set up schools for Indian children orphaned in the great famine of 1837–38 and had trained them to use printing presses and make military tents.

On the outskirts of many towns, both within the Company ’s jurisdiction and outside it , were the cantonments with bungalows where British officers lived with their wives and children. The largest cantonments had not only the military features of parade ground, barracks, armoury and hospital but also social amenities such as decent roads, pleasant gardens, a bandstand and a church or chapel. The cantonments were built at a distance from the crowded Indian cities, both for

pragmatic reasons of health and discipline and for the less tangible reasons of separation from the native inhabitants. Out of necessity, the Indian soldiers, the sipahi or sepoys who formed the majority of the Company’s three great armies, had to live in the cantonments too. However, here again they were markedly separated from the British officers and lived in their own rows of thatched huts.

It was not the number of Britons in India that caused resentment among the local people, because they were less than 100,000 among a population estimated at about 250 million in the mid-1850s. It was what the British had done to India, by usurping its rulers, by interfering in its trade (to the Company’s advantage), by failing to understand the subtle hierarchies of rural life and by devaluing the sepoys’ contribution in times of war and peace. This short introduction is not the place for a detailed analysis of the East India Company’s rule nor for the many reasons put forward for the revolt that started in 1857 and , perhaps, did not finish until 1947 and Independence. For standard histories as well as new accounts of the revolt , see ‘Further Reading’ at the end of this volume. The mutiny of the sepoys was not the first to occur in the Company’s armies, and it was not to be the last. What set 1857 apart from earlier mutinies was the rapidity with which it spread and its targeting of British civilians as well as Company officers. In retaliation, the British quelled the revolt with a previously unknown savagery, killing villagers and townspeople alike—sepoys, civilians, intellectuals, poets and peasants.

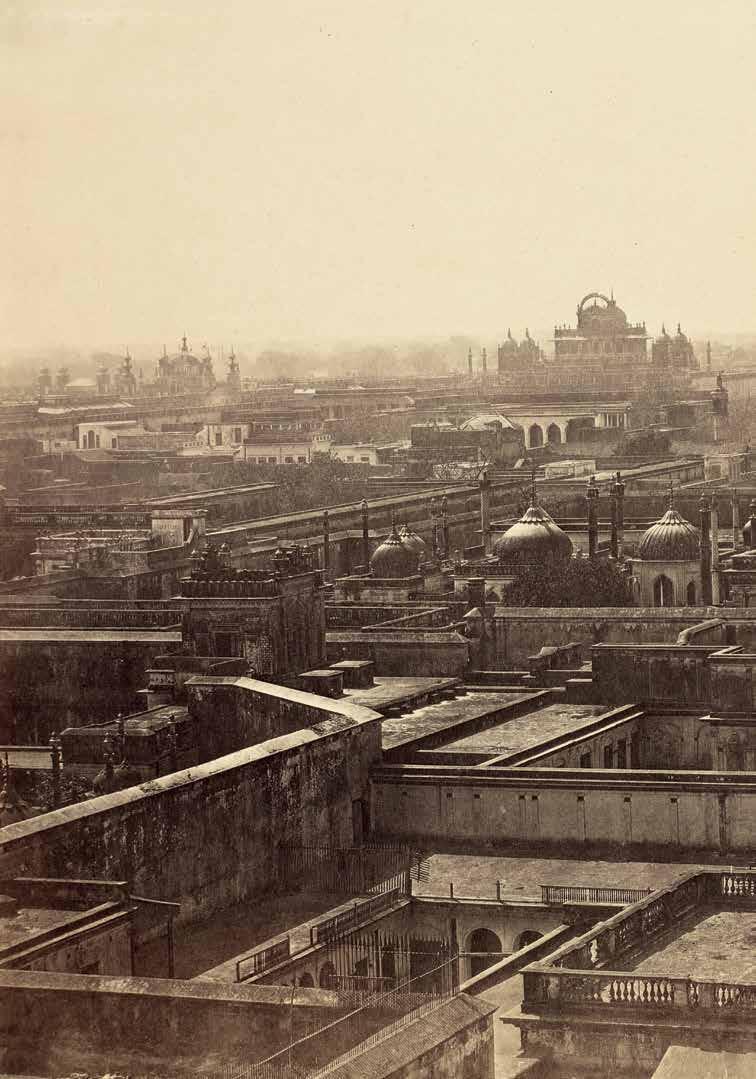

Geographically, the main arena of the fighting and killing was northern India, and particular cities became epicentres of revolt, of resistance against the Company, and of eventual capitulation to its forces. In the confusion of the times, the rustkhez-i-beja as the poet Ghalib described it , 1 many surreal and contradictory events took place. In the Lucknow Residency, the British were besieged by Indian troops. In Delhi, the citizens and rebel sepoys were besieged by British troops. Both cities were recaptured by British officers commanding Indian soldiers, and reinforced by British and Gurkha regiments. Indian administrators working for the Company, including tax collectors and treasury officials, were killed by their fellow countrymen as they defended their employer’s money and records. A small but significant number of Europeans and Anglo-Indians fought with Indians against the British. Indians, divided by creed , caste, tribal loyalties, feudal resentment , personal grudges, envy and greed, sometimes fought each other instead of the real enemy, the British. To present the Mutiny as a straightforward conflict between the oppressed and the oppressors is to oversimplify an intensely complicated event.

Chronologically, the first outbreak was at Meerut on 10 May 1857, although there had been portents since the beginning of the year, one of the most prominent being the protest by the Brahmin sepoy Mangal Pandey, who was courtmartialled and hanged at Barrackpore.2 After torching the cantonment, releasing prisoners from the gaol, looting the treasury and killing Christians, the Meerutbased sepoys marched to Delhi, where they entered the city on the morning of 11 May. The 82-year-old Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, reluctantly agreed to act as their leader. At the same time, Christians in Delhi , both British and Indian , were being slaughtered. British-controlled premises were ransacked, including the Delhi Bank , the electric telegraph office, the Magazine (armoury), Delhi College and the Delhi Gazette printing press. Some Indian-owned shops were also stripped of their contents.

Civil administration was resumed , headed by one of the Emperor’s sons, Mirza Mughal , and military control was subsequently taken on by General Bakht Khan. However, on 20 September, Delhi was recaptured by the British , who had regrouped on the Ridge above the city. A fearful retribution was visited on its inhabitants.

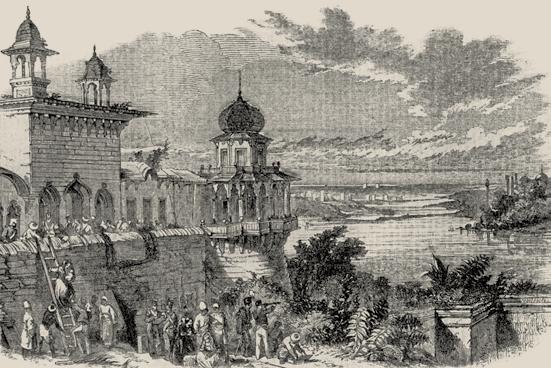

Earlier, in June and July, three massacres of the British in Cawnpore took place, probably instigated by Dhondu Pant, the Nana Sahib. British refugees who had

fled down the Ganges from Fatehgarh to the supposed safety of the Cawnpore cantonment were among those killed. Once again , indiscriminate violence by British troops followed immediately. Britons and Indians trapped in the Lucknow Residency were rescued , at the second attempt, in November 1857 (fig. 1). The winter months were devoted to preparing the city against the inevitable British attack, but in spite of huge barricades thrown up around its outskirts, Lucknow fell in March 1858, after two weeks of fierce street fighting. In central India, the struggle continued until the recapture of Gwalior and Jhansi, and the death of Lakshmi Bai, the Rani of Jhansi. On 1 November 1858, Queen Victoria announced by proclamation that the Government of India was being formally transferred from the East India Company, which was dissolved, to the Crown. There were to be no more annexations of independent states, and new, ameliorative measures were announced. The life-changing and life-destroying events of the preceding 18 months were finally over.

Late in 1857, George Vickers, a London publisher at Angel Court in the Strand , began issuing the Narrative of the Indian Revolt as a pamphlet in weekly parts, priced at one penny. The following year, Vickers bound the instalments together and published them as a book entitled Narrative of the Indian Revolt from its Outbreak to the Capture of Lucknow by Sir Colin Campbell. Vickers boasted that the Narrative was “ illustrated with nearly two hundred engravings from authentic sketches”, and its 450 pages were crammed with newspaper reports and contemporary letters. The book capitalised on the intense interest among the British about the events of the Indian Uprising and provided some of the first pictures of dramatic events. These iconic images included the defence by European civilians and Sikh policemen of a billiard hall at Arrah, and the massacre of 200 British women and children at Cawnpore.

While some of the sketches were certainly authentic, being based on photographs, paintings and sketches made in India before 1857, these were embellished with figures of British soldiers and civilians, and Indian rebels. Lithography, an illustrative process popular in the first half of the 19th century, allowed the editing in, or out , of figures, rather like digital photography today. Under a few of the Narrative ’s plates is the caption , “ from a photograph”; one of these shows the Delhi Bank , where the Beresford family was murdered on 11 May 1857 (fig. 2). Other illustrations, although not acknowledged as such, can be identified from pre-1857 photographs, including the earliest known photograph

of Lucknow, taken by Baron Alexis de La Grange, c. 1849–50. This shows the undamaged road that ran from the main gateway, the Rumi Darwaza, which was subsequently completely destroyed during the fighting.

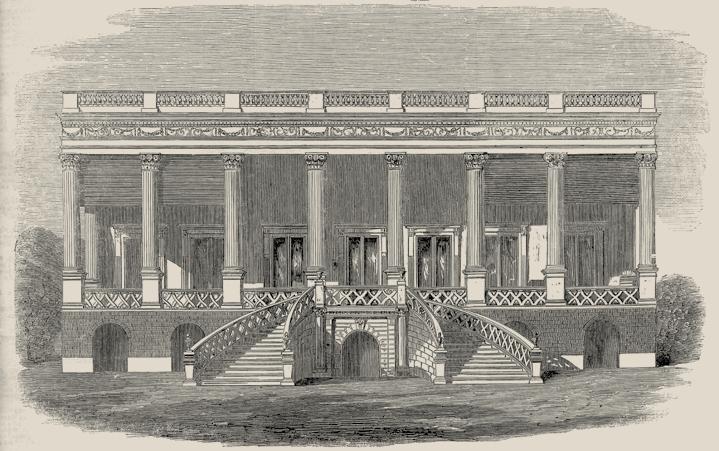

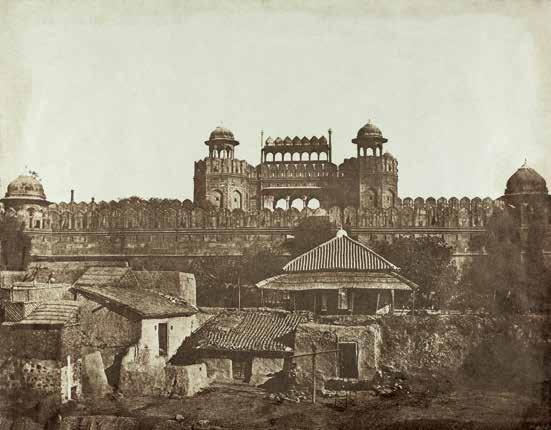

Other plates that were patently engraved from photographs include the “Principal Gate of the Palace of Delhi”, that is, the Lahore Gate of the Red Fort (fig. 3), “St James’s Church , Delhi” and the “ Fort at Agra” 3 The Agra Fort picture is enlivened with added figures, one of whom is a British woman clutching a baby, escaping from the Fort down a ladder propped up against the rampart (fig. 4). In reality, no such escape took place, nor was there any occasion for the British inside the Fort to leave in such a dramatic fashion, but it made a very exciting picture. Some illustrations were purely conjectural, for we know no artist eyewitnesses survived. “Plunder and Murder by the Rebellious Sepoys at Delhi” shows Englishwomen on their knees in front of the sepoys’ bayonets. A child is tossed from a veranda, and an Englishman has been roped to a tree and threatened with a pistol. As well as embellished photographs and imagined events, the Narrative lifted illustrations from other publications. The Queen Mother of Awadh had gone on

above

FIGURE 3 George Beresford [Attributed]

‘The Lahore Gate of the Red Fort’, Delhi from the album Views of Delhi, 1856–1857 Salt Print, 168 x 219 mm ACP: 2001.03.0001(11)

below

FIGURE 4

‘Escape from Agra Fort’- Lithograph from the book Narrative of the Indian Revolt from its Outbreak to the Capture of Lucknow by Sir Colin Campbell, George Vickers, London, 1858

a fruitless journey to England in 1856, to plead for the reversal of annexation that had dethroned her son, the Nawab Wajid Ali Shah. On her way home, two years later, she had died from cancer in a Paris hotel. The Narrative lifted pictures of her funeral in the Père Lachaise Cemetery straight from L’Illustration, the French weekly paper started in 1843. No acknowledgment was given , although moves to protect copyright had begun in the 18th century. The lithographic engravers borrowed freely from whatever material was at hand , even if it was 60 years old or more, and dated from the end of the 18th century. The old Panch Mahalla gateway in Lucknow, sketched by William and Thomas Daniell in 1785, was brought up to date by adding figures to the foreground. One lithograph titled “ The Thugs of India – reparations for strangling a victim” appears to be based on an 18th-century Company painting of a group of pilgrims resting under a banyan tree near a small temple.

A similar book to the Narrative, and as frequently quoted , is Charles Ball’s The History of the Indian Mutiny (c. 1858), which is illustrated by some intensely dramatic and wholly imagined scenes, like the massacre at Cawnpore. Villainous-looking sowar s (Indian cavalrymen) are pictured riding into the Ganges and cutting down Englishwomen and infants with their swords. An Englishman standing on the prow of a curious vessel attempts to defend the women but is shot dead and is seen about to cartwheel into the river. Ball also lithographed unacknowledged photographs, including a pre-Mutiny view of the principal street at Agra by Dr John Murray, the civil surgeon. (See Chapter 9, “Photographing the Uprising”)

The Illustrated London News, a weekly periodical with an estimated print run of 200,000 in the mid-1850s, printed lithographs to accompany reports of the Mutiny, starting in the 26 September 1857 issue. “Sketch among the Remains of the Cantonment Bazaar, Delhi” gave the first pictorial indication of how serious things were for the British in India. Some of the Delhi sketches are attributed to Captain G.F. Atkinson of the Bengal Engineers, whose work is discussed below. The News coverage of the Mutiny was far less sensational than that of Vickers’ weekly Narrative. The News was aimed at a more sophisticated audience and cost sixpence instead of a penny. It carried one ‘action’ picture, the storming of the Kashmere Gate at Delhi by British troops, and a few sketches of Indian prisoners being executed. Some lithographs accompanying written reports were based on photographs, now lost , but these were straightforward copies, without the embellishment of added figures. The News also published small maps of Delhi and Lucknow, with brief descriptions of the recapture of the two cities.

The engravings discussed here, a mix of lithographs, sketches and imagination , were the first published images of the Mutiny; and for this reason , they have sunk deep into the British consciousness and even, to some extent , the Indian mind. They have been frequently reproduced and continue to be published today. Although we know on one level that they are not ‘real’, on another, we can’t help thinking that they do perhaps contain some elements of truth. Constant repetition of these images has given them both authority and , paradoxically, a kind of authenticity, albeit spurious. Literacy rates in Britain increased significantly during the Victorian era, but it is likely that in the 1850s, at the time of the Mutiny, there was still a substantial percentage (about 40%) of illiterate men and an even higher number of women. Popular opinion and public outrage were, thus, as likely to be fuelled by lithographs as by the written word. (Gautam Chakravarty, in his otherwise excellent book The Indian Mutiny and the British Imagination, completely fails to mention pictorial representations thus confining his study only to literate Britons.)

Artists were not slow to realise the potential for dramatic paintings either. An emotive oil painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1858, by Sir Joseph Paton, titled “In Memoriam”. It was, the artist stated, “ designed to commemorate the Christian Heroism of the British Ladies in India during the Mutiny of 1857, and their ultimate Deliverance by British prowess”. The picture showed a small group of British women with their infants, in prayerful postures, as a band of sepoys rush through the doorway. Sir Joseph’s standing, as a member of the Royal Society of Artists, added grativas to this powerful image.4

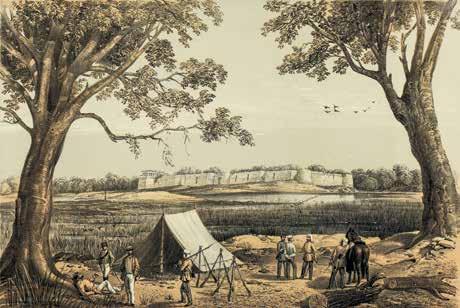

Two books of lithographed sketches were published in 1858, by British officers who were in India during the Mutiny and , therefore, had a better claim to authenticity than the images produced and circulated by Charles Ball and George Vickers. Lieutenant Clifford Henry Mecham was among those besieged in the Lucknow Residency from July to mid-November 1857. Although serving with the Madras Army, he was seconded as Adjutant to the 7th Oudh Irregular Infantry. He published 26 plates of Sketches and Incidents of the Siege of Lucknow: From Drawings made during the Siege, which were lithographed and tinted by Day & Son, the best-known lithographers in London. Mecham’s sketches, which are those of a competent amateur, were annotated by George Couper, an influential man who had been Secretary to the Chief Commissioner of Oudh and whose name frequently appears in official correspondence between Lucknow and government

headquarters in Calcutta. Mecham and Couper’s book appeared in October 1858 and was dedicated to Queen Victoria (figs 5 and 6).

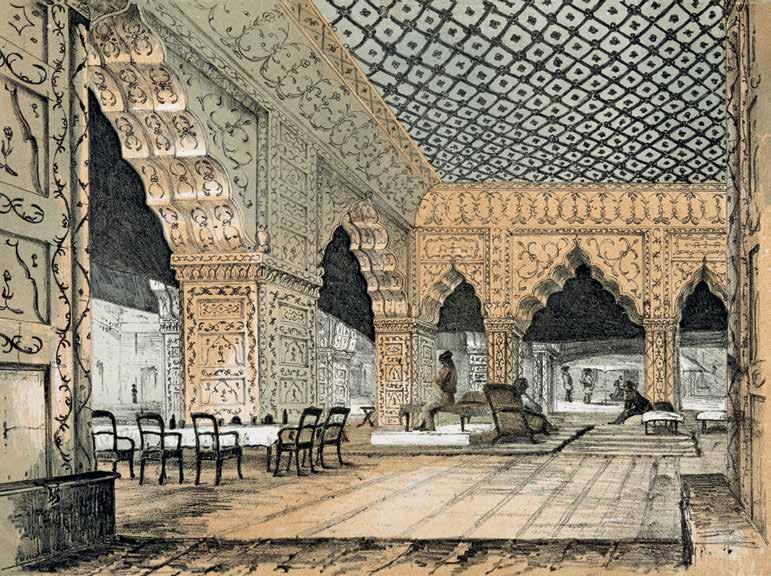

In the same month , Lieutenant Colonel John Robertson Turnbull published Sketches of Delhi , taken during the Siege, made while he was serving as ADC to Major General Sir Archibald Wilson, the officer who led the recapture of the city in September 1857. Turnbull’s sketches, which he appears to have lithographed himself, are coloured in sombre shades of grey and beige, and picture some specific buildings connected with the siege, including Flagstaff Tower and Hindu Rao’s house. From his vantage point , in the British camp on the Ridge above Delhi, Turnbull’s melancholy panoramas show the scrubby landscape that Felice Beato was to photograph the following year. Turnbull’s last plate, a view that could not be captured photographically, is captioned “Easy Times or the Kafir in the Palace of the Mogul” and was drawn in the Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience) of the Red Fort. General Wilson established his headquarters here in the private apartments of Bahadur Shah Zafar, who had abandoned them on 18 September (fig. 7). Turnbull’s sketch shows the British officers’ chairs drawn up around a large table, below the magnificently decorated ceiling. The kafir (unbeliever), of course, was an ironic reference to the Christian officers, now relaxing in the Muslim king’s palace after its capture and the flight of its owner.

On 1 January 1859, Captain George Franklin Atkinson published The Campaign in India, 1857–58 sketches, another book of 26 plates lithographed by Day & Son. Atkinson’s sketches are the weakest and least authentic of the three eyewitness accounts discussed here. Some relate to specific events, such as the image captioned “Storming the Batteries at Badle Serai”, but the majority are non-specific images with captions like “Repulse of a Sortie” and “Interior of a Tent”. None bear much resemblance to any of the real places connected with the Mutiny, and there are far too many men on horseback rushing around to be properly captured images by a poor artist.

Although not expressed in so many words, there was undoubtedly competition to put the first authentic images and accounts before the British public by those who had lived through the dramatic events of 1857. Martin Gubbins, the financial commissioner who had been trapped with others in the Lucknow Residency during the siege, finished writing his Account of the Mutinies in Oudh and of the Siege of the Lucknow Residency in Brighton on 3 June 1858; it was in print two months later. Nevertheless, Gubbins felt it necessary to explain that publication had been

left

‘No. 6 Front View of the Residency’ from the book Sketches and Incidents of the Siege of Lucknow by Lieut. C.H. Mecham, London, 1858

Coloured Lithograph, 234 x 359 mm ACP: D2005.42.0001(07)

delayed through his own illness and because the first half of his manuscript had been lost at sea when the P&O steamer Ava struck a rock off the coast of Ceylon on 16 March. All her passengers were saved, but among the baggage lost were “many admirably executed illustrations of the scenes around the Residency by the pencil of Colonel Vincent Eyre, Bengal Artillery, and Captain W.H. Hawes of the 5th Oudh Irregular Infantry ” . 5

Only one contemporary artist has accurately captured what the revolt was really like, with its sudden brutality, the sepoy prisoners in irons, and scenes in the British miliary camps. This was the Swedish artist Egron Lundgren , who was commissioned by Queen Victoria to provide her with watercolours from India. With a contract from the Manchester art dealers Agnew & Sons, Lundgren arrived in Calcutta in March 1858 but did not see action until the end of November that year, when he was with Sir Colin Campbell’s force, which was hunting down the last of the rebel leaders, Beni Madho. The sketches of fighting at Daundia Khera, during which about 800 Indian soldiers were killed, are graphic in their depiction of the dead or dying men and horses fallen in a cavalry charge. Lundgren’s diary was no less explicit than his drawings where he described the battlefield as “a sight of unspeakable suffering” 6

‘No.

Coloured Lithograph, 239 x 359 mm ACP: D2005.42.0001(24)

There is an intriguing link between the artist Lundgren, the photographer Felice Beato, and war correspondent for The Times, W.H. Russell. Lundgren drew some of the illustrations for Russell’s book on the Mutiny titled My Diary in India , in the

‘Easy Times or the “Kafir in the Palace of the Mogul”’ [the Diwan-i-Khas converted into an Officers’ Mess for General Wilson’s Headquarters] from the book Sketches of Delhi taken during the Siege, published by T. McLean, London, 1858

Lithograph

Courtesy: The British Library Board (Shelfmark: 1261.e.31/14)

Year 1858–59, published in 1860. One of these, “The Sacking of the Kaiser Bagh”, is an imaginary reconstruction of the looting of the Qaisarbagh Palace in Lucknow, by British and Gurkha troops in March 1858. Lundgren also ‘ borrowed’ one of Beato’s photographs of the barricades at Lucknow and based a watercolour on it. The artist removed the battered tree and most of the figures from the photograph but considerably enlarged the Begam Kothi Palace in the background. None of these three most accurate reporters of the Mutiny— Lundgren, Beato and Russell were British.7 Almost certainly, this enabled them to see the Indian tragedy that unfolded in front of them more objectively than their British counterparts.

In contrast to the race to bring memoirs and sketches to the public, there were delays in bringing the Mutiny photographs to Britain, and there is uncertainty about how widely they were seen when they did arrive. Even news reports, brought from India by steamer to Suez, then overland to Alexandria and across Europe by telegraph, could still take five weeks to reach Britain. Photographs by Felice Beato, the first commercial photographer in India during the Mutiny, were

FIGURE 7 John Robertson Turnbullfollowing pages

on display and sale in Calcutta by August 1858, and during the winter of 1858–59, they were displayed in London at the Photographic Society’s exhibition. But they did not appear in the Illustrated London News, which would have ensured a wider circulation. At the end of 1861, Beato sold them to a London dealer, who duplicated them and offered the ‘complete India series’ to the public for £54 a set, thus ensuring their exclusivity. Dr John Tresidder, (a British doctor in the Indian Medical Service between 1842 and 1877) and a gifted amateur who photographed Cawnpore in 1858, did not exhibit in London until 1862; his work then disappeared from public view. Ironically, a number of glass negatives and photographs taken in Lucknow shortly before the outbreak of the Mutiny, and thus of great topical interest, were in Britain by the middle of 1858 but were never made public. These were the work of the local photographer Ahmad Ali Khan, also known as Chhote Miyan (fig. 8). How they arrived in Britain is narrated in detail by the biographer of Lieutenant-Colonel Gould Hunter-Weston, who looted them from Khan’s house.

“ In the days before the Mutiny, Ahmud Ali , [Ahmad Ali Khan] who was the Darogha, or Superintendent of the Imambarah of Mahomed Ali Shah, the King of Oudh who died in 1842, had ingratiated himself with a British officer, who taught him photography. He soon made creditable progress in the art , and brought himself into notice. Through Ali Naki Khan, the corrupt Prime Minister, he was appointed Court photographer and the King, Wajid Ali Shah, permitted him to take, under the strictest instructions of secrecy, the likenesses of his Queen, and the ladies of the Royal Harem. ‘During the Mutiny ’ (to use now Gould Hunter-Weston’s own words), ‘Ahmud Ali, naturally enough, fought against the defenders of the Lucknow Residency, and on the capture of the city in March 1858, his house was one of those from which, aided by a detachment of the 20th (now the Lancashire Fusiliers), I cleared out some of the rebels. My loot consisted of two small cases containing negatives, and a bundle of hastily collected photographs, which, unhappily, turned out to be ‘ failures’. But I recognised that even these imperfect copies were of great interest and value; many of the buildings had been injured or destroyed during the siege; many of the native gentlemen portrayed had been killed, had died, or were in hiding; and the photographs of the ladies of the harem were, of course, unique. Thus, indifferent as they undoubtedly were as works of art, I brought these photographs home, with me, and, while residing at Annanhill in 1864, mounted them in this book.”8

Unfortunately, “ this book” with Khan’s mounted photographs appears to have been lost, or at least mislaid. Only two of the photographs are known, because they were reproduced in the biography of Colonel Hunter-Weston, published in 1914. They show the Dilaram House, where he lived for several years, and an intimate picture of the last nawab of Awadh, Wajid Ali Shah, with one of his wives and a child (see Chapter 5, fig. 1). One of Khan’s photographs was lithographed as the frontispiece for Martin Gubbins’ book , mentioned above. Gubbins does not say how he obtained the original, but given that Gubbins was a prominent Company official and that Ahmad Ali Khan was known to make generous presents of his photographs, it may have been a gift.

Commercial photographers were subsequently to visit Mutiny sites for many years after the dramatic events of the Uprising. As late as 1892, John Dannenberg was able to market views of Lucknow and Cawnpore taken around the year 1859, under the title Mutiny Memoirs. The amateur photographer Darogah Abbas Ali , published his Lucknow Album in 1874, containing views of the city taken in the 1860s at sites connected with the Mutiny, in an attempt to illustrate “ the hardships suffered by the glorious Garrison of Lucknow ”

Photographs of the Mutiny, however, were not in wide circulation in Britain during 1858, so the general public continued to picture it through the available lithographed and painted images. Indeed , even if it were technically possible to have immediately presented the photographs of 1858 to a British audience, there would only have been disappointment that they showed no dramatic battle scenes

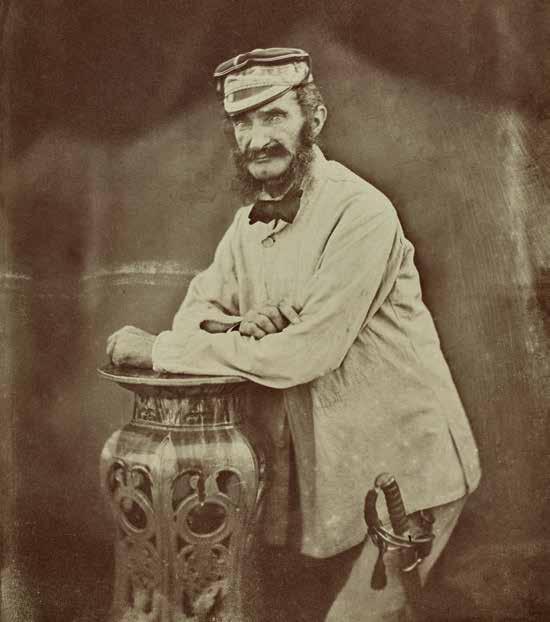

nor British women and children being rescued , and nothing of the recapture of Delhi by British and Sikh troops. What they did show, in a series by Dr John Murray, were the ruined streets inside the Delhi walls, with a solitary, turbanned figure squatting outside his looted house (fig. 9). The area between the Ridge and the Delhi walls, the scene of skirmish and counter-skirmish , was shown as an empty, scrubby wasteland with non-photogenic bushes. When Felice Beato arrived immediately after its recapture by the British in March 1858, Lucknow did, in fact, have some magnificent buildings, but it was difficult to imagine the now-empty streets filled with fighting men and fleeing women, as had been the case only weeks earlier.

British officers involved in the campaign had, of necessity, to be shown in ‘studio’ portraits, a sheet rigged up as a backdrop and an ornamental iron table as a prop, rather than at the head of their troops (fig. 10). The enduring popularity of the print is demonstrated by such portraits as Thomas Barker’s “ The Relief of

FIGURE 10 Unknown Photographer

Sir Hope Grant from the album Views in Lucknow, Cawnpore and Delhi, 1858–1859

Albumen Print, 188 x 150 mm

ACP: 98.77.0001(03b)

FIGURE 10 Unknown Photographer

Sir Hope Grant from the album Views in Lucknow, Cawnpore and Delhi, 1858–1859

Albumen Print, 188 x 150 mm

ACP: 98.77.0001(03b)

Lucknow ”, where the three generals Havelock, Outram and Campbell are shown meeting in heroic mode in front of exotic buildings, conforming precisely to public expectation (fig. 11). Captured rebels such as Jwala Pershad , a risaldar (cavalry commander), were photographed seated on a wooden chair, their limbs in irons. There are no known photographs of Nana Sahib, of Azimullah Khan, of Begam Hazrat Mahal or the Rani of Jhansi. Only Kanwar Singh, the Raja of Jagdishpur whose military adroitness became a serious threat to the British, has been captured by the camera. He sits in a wooden carrying-chair, a helpless old man with a white beard but surrounded by armed attendants (fig. 12).

Thus, British public reaction to the Mutiny was initially based largely on emotive and often imagined pictures, rather than photographs, although by 1857 photography was not a new art, being already two decades old. War photography was not a new concept either. It was first employed during the MexicanAmerican war of 1846–48 and, subsequently, in the Crimean war of 1854–56. Yet , the idea of photographs being used as immediate images that could sway political thinking, as was to happen in the 20th century, could not be

applied to the Mutiny images. It is only today, as these photographs come to light, that we can use them as tools in our understanding of what happened in India in 1857–58. Indeed, the importance of these images themselves has only recently been acknowledged. It was not until the 1980s that a volunteer at the India Office Library, the repository of the largest public collection of 19th-century Indian photographs, began cataloguing them onto a card index, and it was only from 1993 that the Library’s first database catalogue was set up, with external funding.9

In examining the Mutiny as an important historical event, the lack of referenced photographs has been paralleled, in a curious way, by the perceived lack of Indian sources. One Indian historian has estimated that some 60,000 manuscripts lie unread in provincial Indian archives, because the documents are uncatalogued and because the Persianised Urdu in which they are written is almost unknown

among present-day researchers.10 Despite this, there is solid ongoing Mutinyrelated research by scholars in India, or scholars of Indian origin elsewhere in the world. During the last 30 years, the so-called “Subaltern Studies” has evolved into a recognised genre, examining the role of lower-caste or lower-class Indians in the Uprising. This field of study moves the debate away from the traditionally romanticized Indian heroes and heroines like Begam Hazrat Mahal and focuses on peasants, Dalits and other oppressed groups who participated in the insurgency. There are other partisan groups too, including the Marxists who want to claim the Mutiny as an early attempt by the rebels to shake off capitalism, and those who are still using 19th-century British accounts, with little critical analysis.

Mutiny studies in India have now moved on from the purely narrative. Today, we are in the post-narrative phase of such studies.

Similarly, deconstruction , particularly of ‘colonial’ photography, is currently a flourishing discipline.11 However, as previously discussed, it is also important to consider the people who had access to these photographs and whether they saw the images as the events were taking place or years later. There is also the danger of neglecting the actual photograph and reading too much into the mind of the person behind the lens. Certainly, commercial photographers like Beato wanted images that would sell and were not too scrupulous about how they were obtained. Sometimes it is as simple as that.

This book marries little-known photographs with new texts on the Mutiny by current scholars. Both are equally important in advancing the study of events that took place over 150 years ago and are still open to new interpretations. The contributors have deliberately chosen previously little-known, or little-examined, aspects of the Mutiny. The previously underrated importance of mapping the campaigns is examined here together with the fate of two of Delhi’s prominent intellectuals. A brief chronology places the major events and characters in order.

For the most part, the photographs presented here speak clearly for themselves. As the writer Omar Khan has said, “A photograph shatters the glass between the present and the past… A photograph is a bullet shot from the past into the future.”12 There can be no description more apt for the Mutiny photographs in this book.

1. Rustkhez-i-beja is a clever chronogram, whose numerical value works out at 1273 hijri (the year of the migration of Muhammad and his followers from Mecca to Yathrib), equivalent to A.D. 1857.

2. The 14 members of the court-martial who tried Mangal Pandey on 6 April 1857 were all Indian officers. Only the Judge Advocate and the prosecutor were British officers. Pandey was found guilty by all 14, and a majority of 11 voted for the death penalty.

3. The Agra photographs were almost certainly the work of Dr John Murray, a talented amateur photographer. See Chapter 9 “Photographing the Uprising” in this volume.

4. The implication that the sepoys were about to attack the women was considered so offensive when the picture was shown at the Academy that the artist subsequently painted out the sepoys and painted in Highland soldiers coming to the rescue.

5. One sketch by Colonel (later Major) Vincent Eyre was published in the Illustrated London News on 12 December 1857. It showed the “Little House at Arrah,” the one-time billiard hall defended by Eyre, a few European civilians and 50 Sikh policemen against the army of Raja Kanwar Singh.

6. Narayani Gupta and Sten Nilsson, The Painter’s Eye: Egron Lundgren and India (Stockholm: National Museum, 1992), 115.

7. Egron Lundgren was Swedish, Felice Beato was born in Corfu, of Italian parentage, and William Howard Russell was Irish.

8. W.L. Low, Lieutenant-Colonel Gould Hunter-Weston of Hunterston; A Biographical Sketch (Scottish Chronicle, 1914).

9. Information courtesy John Falconer, Curator of Photography, the British Library.

10. Prof. S.M. Azizuddin Husain, “1857 as reflected in Perisan and Urdu Documents” (Paper presented at the Mutiny at the Margins conference, Edinburgh University, June 2007).

11. Articles on colonial photography are invariably signalled by the words “image” or “imaging” in their titles.

12. Kurt Meyer and Pamela Deuel Meyer, In the Shadow of the Himalayas: Tibet, Bhutan, Nepal, Sikkim: A Photographic Record by John Claude White, 1883–1908 (Ahmedabad: Mapin, 2005), 13.

a view from the delhi ridge and cavalry lines

Shahid Amin

In retrospect, it was photography—the thousands of frames of blasted ruins, hanged rebels, mutilated corpses rotting down to strewn bones—that held 1857 up as an object lesson in the logic of empire for all colonial masters and their subjects. Imperial domination was also inscribed through the unrelenting Stones of the Empire—the bombed-out Residency at Lucknow, the conical victory memorial on the Delhi Ridge—intended to monumentalise the Mutiny for posterity. And finally, as is its wont, came History. English History, written almost in the manner of the classic accounts of the Mughal royal hunt… the hounding of game gone wild into ever-shrinking enclosures for the final, historic coup de grace.

I propose to view the photographs in this essay not as “amoral” pictures of past reality but as images and texts suffused with the unique and profoundly disturbing ethos of the times in which they were produced. This chapter is not so much about historical evidence offered by photographs of violence, as about the reading of a work of “official” history. Just as with the dialectical relationship of master-slave, ruler-ruled, victor-vanquished, histories of rebellions cannot be written without reference to the accounts of the dominant. Indeed, it would be a powerful yet illusory revenge, a quaint magical realism of sorts, were we to deploy mechanisms of erasure and conjure a history of anti-colonialism in India without once mentioning the British or their meticulously maintained colonial records.

One such testament, the most authoritative and influential among the voluminous documentation that appeared in the aftermath of the Great Revolt, was the massive three-volume A History of the Sepoy War in India by Sir John William Kaye. The History was a commissioned piece that enjoyed the support of the AngloSaxon public in Calcutta and the mandarins at the India Office in London. As early as 1859, the Calcutta Review had placed John Kaye on its shortlist of potential authors, second only to Macaulay, for chronicling the authentic account of the English endeavour during 1857–58.1 By the time Kaye sat down to writing it, he

had personal communications from the main actors of this high drama, and records were graciously loaned by the India Office where he held a senior position.2 As we shall see, he chose to rely chiefly on the former sort of testimony. Kaye produced the first three volumes between 1864 and 1876 dying almost immediately afterwards.

When it first appeared, A History of the Sepoy War in India was seen, despite its lofty claim of telling “nothing but the Truth”3 to be partisan in its treatment of Dalhousie and Canning and unreasonably critical of the annexationist drive of the British imperialists in India. In a lengthy résumé, the historian of the English historiography on the Indian Mutiny shows how these in turn were motivated by the parti pris of the time.4 Many subsequent writers have pointed out that while Kaye often gives the impression of being the first historian of certain episodes and events, he was, in fact, following in the wake of other, perhaps lesser, chroniclers of the Mutiny. Kaye has also been criticised for his unbalanced evaluation of the incidents of cruelty and barbarism during the rebellion. Others have argued that he does not give as complete an account of some of the celebrated episodes of the Uprising as he possibly could have.5

Despite all criticism, however, what we have in Kaye’s book is a phenomenal amount of material, almost a day-by-day account spread over the many theatres of the War. Even a cursory look at the detailed table of contents and the subsections of the chapters makes this quite clear. Not only does Kaye pack in a good deal of information about the various mutinies of 1857 and of the period before that, but he also provides a fairly detailed account of the background to the Uprising, especially the trials and tribulations of Awadh in the decade preceding the annexation of that kingdom.6

Subsequent research into the annexation and its consequences has focused on the popular resistance to the British by providing insights into the links between the mutiny of the sepoys and the émeute in the countryside. Rudrangshu Mukherjee’s study of Awadh, 1857–58, isolates the districts of Bahraich, Gonda, Faizabad, Partabgarh and parts of Rae Bareli as the core areas of resentment and rebellion against the Company sirkar (government). These districts, dominated by taluqdars (large “feudal” landholders), had suffered the most during the revenue settlement of the immediate post-annexation year. These were the territories from which a large number of peasants were inducted to fight the Company’s wars as sepoys and from where the taluqdars marched with their retainers and peasants to besiege and harass the British in and around Lucknow during the Great Rebellion.7

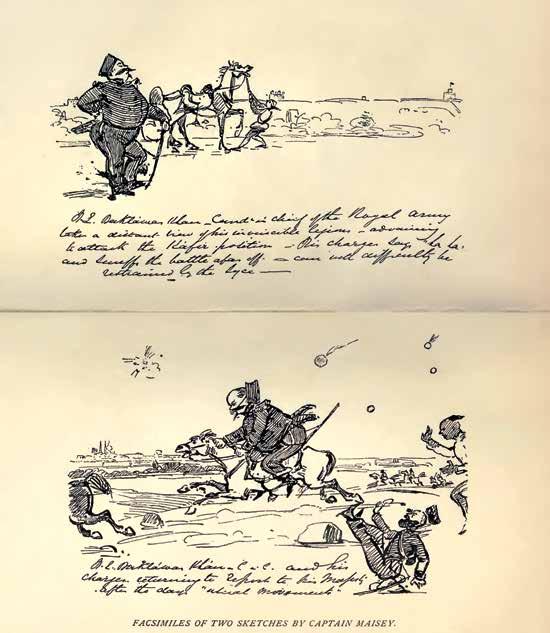

Two caricatures of General Bakht Khan, Commander-in-Chief of the Delhi Army during the Siege from Delhi 1857: The Siege, Assault, and Capture as given in the Diary and Correspondence of Late Colonel Keith Young edited by Sir H.W. Norman & Mrs Keith Young, published by W. & R. Chambers, Limited, London & Edinburgh, 1902

The mutinies in the cantonments of northern India were not random irruptions; they sparked systematically down the Ganges valley, from Meerut and Delhi, “with a time-gap between the various stations required for the news to travel from one place to another.”8 Delhi and Lucknow were symbolic victories that precipitated mutinies and rebellion elsewhere. The violence of the sipahis was not indiscriminate; rumours about the intention and deeds of the Angrez (English), coupled with prophetic proclamations about the end of firangi-raj (foreign rule) provoked a simmering violence among the mutineers (fig. 1). The injustice done to Nawab Wajid Ali Shah in deposing him was felt generally. As a popular

THE ALKAZI COLLECTION OF PHOTOGRAPHY

264 pages, 168 black & white illustrations

9.5 x 10.75” (242 x 275 mm), hc

ISBN: 978-93-85360-11-4 (Mapin)

ISBN: 978-1-935677-58-1 (Grantha)

₹3500 | $70 | £55 2017

Rosie Llewellyn-Jones read Urdu and Hindi at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). Her PhD was subsequently published as A Fatal Friendship: the Nawabs, the British and the City of Lucknow in 1985. She has written extensively on India during the colonial period, and edited Lucknow: City of Illusion, the first book in the Alkazi Collection of Photography series (2006). She was Secretary of the British Association for Cemeteries in South Asia (BACSA) for ten years and is the founder and editor of its journal, Chowkidar. She is based in London, visiting India regularly.

Shahid Amin is currently visiting Professor in history at Columbia University, New York and was Professor of History at Delhi University Mahmood Farooqui is an Indian writer and director. He specializes in a type of storytelling known as Dastangoi.

Nayanjot Lahiri is Professor of History at Ashoka University. She is the 2016 awardee of the John F. Richards prize for her book Ashoka in Ancient India

Andrew Ward is an American writer of historical nonfiction. He is a former contributing editor to Atlantic Monthly and columnist for the Washington Post

Tapti Roy is an academic professional with over thirty years of experience in teaching and research. She is the author of The Politics of a Popular Uprising: Bundelkhand in 1857 (1995) and Raj of the Rani (2006).

Susan Gole has been the Chairperson of the International Map Collectors Society for nine years, as well as the Editor of their journal. Gole has written extensively on the pre-1800 cartographic traditions of India in publications such as Early Maps of India (1976) and Maps of Mughal India (1990).

Zahid R. Chaudhary is currently Associate Professor at Princeton University, specializing in postcolonial studies, visual culture, and critical theory.

Stéphanie Roy Bharath is a photo researcher and has studied Art History in Paris and London. She was previously Curator of the Alkazi Collection of Photography in London.

other titles of interest

Celebrating Rahim

Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan

Edited by Shakeel Hossain

Paper Jewels

Postcards from the Raj Omar Khan

Indian Troops in Europe: 1914–1918

Santanu Das