January/February 2022

DO HOUSE DEMOCRATS REALLY HATE ONE ANOTHER? GRACE SEGERS

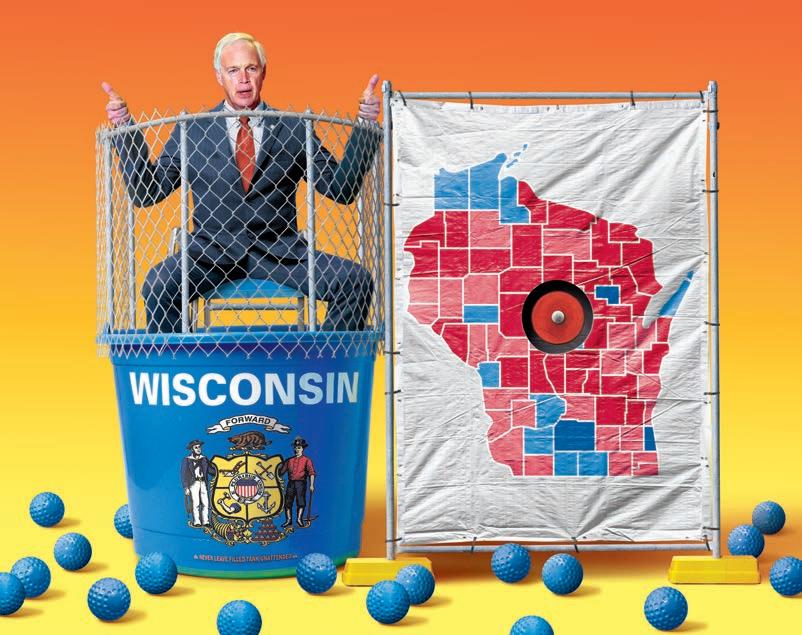

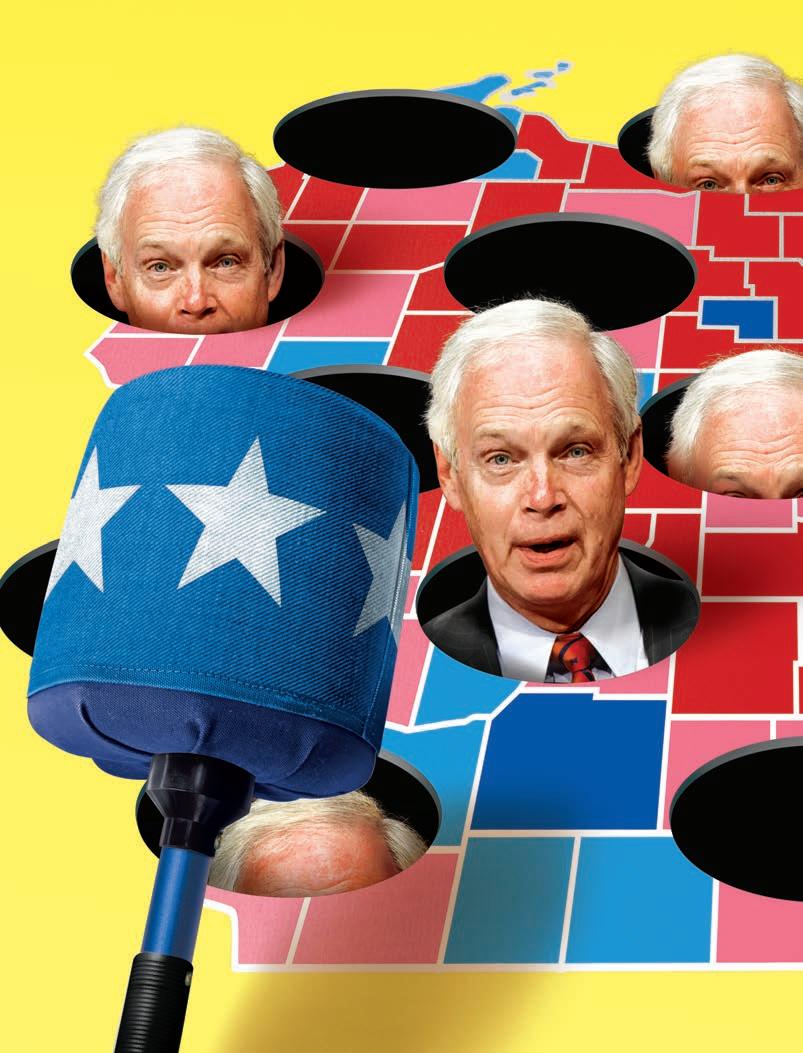

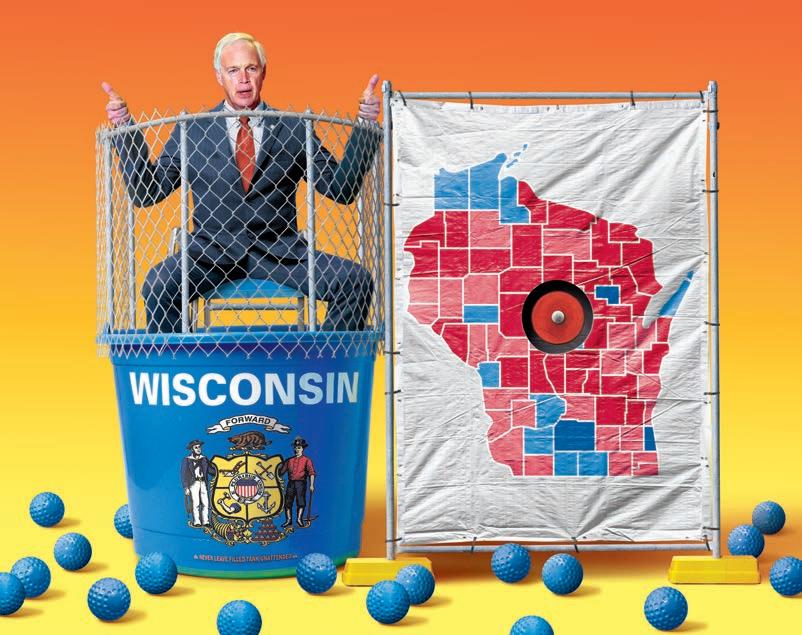

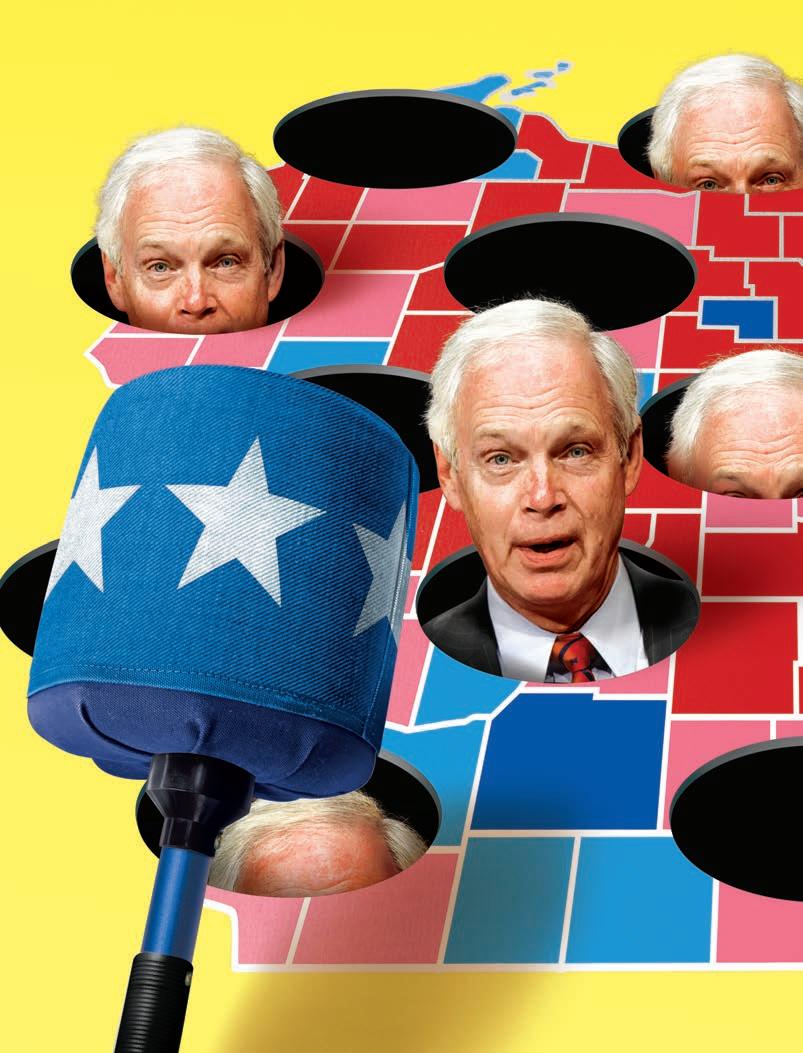

THE GOP SENATOR THE DEMOCRATS WOULD LOVE TO BEAT

DANIEL STRAUSS

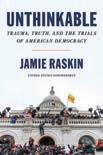

DEMOCRACY ’S DEFENDER

HOW JAMIE RASKIN BECAME THE MAN FOR THIS HISTORICAL MOMENT

POWER NETWORKER MOIRA WEIGEL

NEW IN-CROWD

VOGHT

MICHAEL TOMASKY PETER THIEL,

WASHINGTON’S

KARA

A podcast from The New Republic exploring the intersection of culture, politics, and media

Hosted by TNR’s literary editor Laura Marsh and contributing editor Alex Pareene

Recent episodes:

The Lyme Vaccine That Got Away

Twenty years ago, you could get a vaccine for Lyme disease. Now you can’t. What happened?

More Reasons to Hate the Dentist

Is the field of dentistry rife with overtreatment?

The Unnatural Endurance of Bipartisanship

How did “working across the aisle” become the goal and not merely the means?

The Case of the Sick Spies

Has Russia been zapping American embassies with a secret weapon?

Listen now at

How the Christian nationalist movement’s well-funded strategists are aiming at voters in Virginia and beyond

The lib-trolling Trump sycophant is certainly beatable in 2022. But that’s what everyone thought in 2016, too. 12

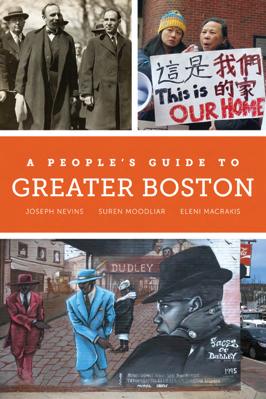

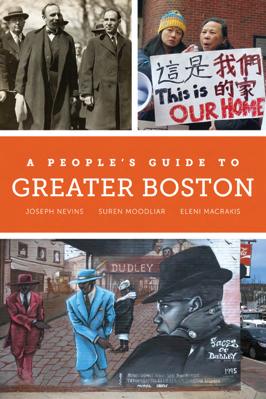

1 Table of Contents January-February 2022 Features 12 Democracy’s Defender Michael Tomasky

this historical moment 22 “And then—boom!” Jamie Raskin An excerpt from the forthcoming book UNTHINKABLE: Trauma, Truth, and the Trials of American Democracy 24 House Democrats Are Grace Segers Not in Disarray. Mostly.

quarrelsome bunch.

is this just what politics looks like? 30 The Shock

Katherine Stewart Next Big Lie

2024 38 Can the Democrats Take Out Daniel Strauss Ron Johnson?

How Maryland Representative Jamie Raskin became the man for

The House Democratic Caucus is often accused of being a

But

Troops of the

for

Democracy’s Defender

LEFT TO RIGHT: GREG KAHN

THE

MATT MAHURIN

30 The Shock Troops of the Next Big Lie

FOR

NEW REPUBLIC;

(ILLUSTRATION)

Cover Photograph by Greg Kahn. Grooming by Alexis Arenas

January-February 2022 2 The New Republic State of the Nation 4 Life of the Party

have a

they’re at it. Kara Voght 7 In the Pipeline Joe Biden wants to

of money save Benton Harbor, Michigan? Derek Robertson 10 Back to Work

Jennifer Abruzzo,

nlrb is

to do. Timothy Noah 5 Democracy Watch 6 Spot the Fake Right-Wing Book Title 8 Who Said It Books & the Arts 46 Only Connect The significance of Peter Thiel does not lie in his personality—but in his networks. Moira Weigel 52 The War Racket What turned a star of the Marine Corps into a critic of U.S. foreign policy? Patrick Iber 56 Fanatics in Freedom How Emerson and Thoreau glorified the individual Sarah Blackwood 60 His Favorite Murder Fyodor Dostoevsky’s love-hate relationship with true crime Jennifer Wilson 63 Franco’s Remains In Parallel Mothers, Pedro Almodóvar reckons with the legacies of fascism. Lidija Haas 65 The Biography Trap Vivian Maier’s genius is on film, not in her life story. Jeremy Lybarger Poetry 58 War No More Rickey Laurentiis 67 Everything Lies in All Directions Hua Xi Editor in Chief Win McCormack Editor Michael Tomasky Magazine Editorial Director Emily Cooke Literary Editor Laura Marsh Managing Editor Lorraine Cademartori Deputy Editor Patrick Caldwell Design Director Andy Omel Photo Director Stephanie Heimann Production Manager Joan Yang Poetry Editor Cathy Park Hong Contributing Copy Editor Howery Pack newrepublic.com Digital Director Mindy Kay Bricker Executive Editor Ryan Kearney Deputy Editors Heather Souvaine Horn Jason Linkins Katie McDonough Contributing Deputy Editor Cora Currier Art Director Robert A. Di Ieso Jr. Staff Writers Kate Aronoff Matt Ford Melissa Gira Grant Josephine Livingstone Timothy Noah Grace Segers Walter Shapiro Alex Shephard Jacob Silverman Daniel Strauss Contributing Writer Molly Osberg Copy Editor Kirsten Denker Social Media Editor Hafiz Rashid Contributing Andrew Schwartz Social Media Editor Front-End Developer Clark Chen Product Manager Laura Weiss Reporter-Researchers Shreya Chattopadhyay Julian Epp Annie Geng Blaise Malley Interns Candy Chan Jessica Moss Editor at Large Chris Lehmann Contributing Editors Rumaan Alam Emily Atkin Alexander Chee Michelle Dean Siddhartha Deb Ted Genoways Jeet Heer Patrick Iber Kathryn Joyce Suki Kim Nick Martin Bob Moser Osita Nwanevu Alex Pareene Publisher Kerrie Gillis Chief Financial Officer David Myer Associate Publisher, Art Stupar Circulation and New Business Development Sales Director Anthony Bolinsky Marketing Director Kym Blanchard Engagement Manager Dan Pritchett Engagement Associate Matthew Liner Executive Assistant/ Michelle Tennant-Timmons Office Manager Lake Avenue Publishing 1 Union Square West New York, NY 10003 For subscription inquiries or problems, call (800) 827-1289. For reprints & licensing, visit www.TNRreprints.com.

Lefties

seat at Biden’s table. And they’re having a blast while

remove lead from drinking water. But can an infusion

Under

the

finally acting on what it was created

Must reads for your inbox tnr.com/newsletter TNR podcasts and audio features Trending news and TNR commentary Politics, health care, media, and Jason Linkins’s “Power Mad” The week’s top articles Climate ideas and updates Inequality, labor, justice, and how we live now Sign up now at Newsletters MONDAY—FRIDAY MONDAYS WEDNESDAYS THURSDAYS SATURDAYS SUNDAYS FRIDAYS Books, arts, and culture

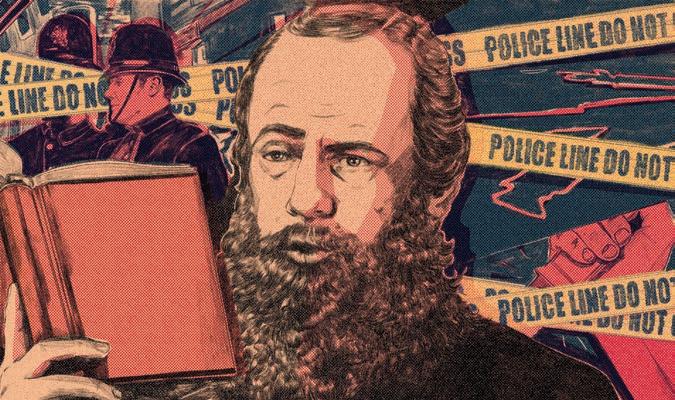

NATION OF THE STATE

Life of the Party

Lefties have a seat at Biden’s table.

And they’re having a blast while they’re at it.

By Kara Voght

Illustration by Bijou Karman

ONCE A MONTH, in the latter, vaccinated half of 2021, denizens of D.C.’s progressive ecosystem flocked to a bar in Washington’s Adams Morgan neighborhood for a happy hour hosted by the pollster and think tank Data for Progress. December’s gathering took place on an unseasonably warm evening,

perfect weather for the youngest members of the Beltway left to network and drink.

Staffers from the Sunrise Movement sipped cans of Narragansett beer as they mingled with aides to Representatives Jim McGovern and Maxine Waters. A contingent from the Omidyar Network, a top progressive investor, stood in a circle near the bar. People were excited to spot Matthew Yglesias, the Vox co-founder who took his vexatious brand of liberalism to Substack—if only because

they seemed eager to dunk on his tweets in person. By 8:30, I’d had two tequila sodas and as many conversations retreading grievances against Neera Tanden, a White House senior adviser and establishment bogeyman among the Bernie crowd.

The White House held its Christmas tree lighting ceremony that evening, so the pair of President Joe Biden’s press aides who’d attended the previous month’s gathering were absent. So was the cadre of regulars

January-February 2022 4

from Senate Democratic offices—“too busy trying to make into law all that shit people talk about at those happy hours,” one senior aide texted me. Even so, roughly 100 members of the Beltway’s progressive sphere had crammed onto the rooftop by the evening’s peak, generating a din that drowned out the bar’s early aughts pop playlist.

Sean McElwee, Data for Progress’ executive director and uncompromising leftistturned-pragmatist, spent much of the night holding court near a high-top table close to the center of the crowd, pounding what would be the first of many nonalcoholic beers. “It’s about discipline,” McElwee told me, referring to both his newfound teetotaler status and his general wish for the progressive movement. He keeps pointing me to Marcela Mulholland, Data for Progress’ 24-year-old political director, for all official statements. (We’re both deep into the Huma Abedin memoir, so we gossip about that instead.)

McElwee’s weekly New York happy hours were among the most documented artifacts in the lead-up to the 2020 presidential election. His East Village guests were “really left people, not party hacks,” an attendee told FiveThirtyEight in December 2018. By the time New York profiled the events four months later, the magazine observed, “Democratic politicians in nice clothes Uber in to kiss McElwee’s ring and gain the trust of New York’s young socialist power elite”— held up as proof that the American left was ascendant as the country chose its next president.

Before the Biden administration, McElwee’s D.C. satellite happy hours had been low-key affairs. Now, the outsiders are closer to the inside—and there’s a lot more of them. Data for Progress is in the White House’s regular rotation of pollsters. The climate activists who once pressured the Biden campaign now sip beer as employees of the departments of Energy and Transportation.

Washington is a town where progressives are often the skunks of the party, rarely the hosts of well-attended, quasi-professional networking events. But that was before Joe Biden, noted centrist and policy agnostic, wrestled the White House away from Donald Trump. When victory came, he had a party to heal, a White House to staff, and an agenda to write. There were few better ways to hit those notes than to welcome progressives, the primary keepers of the wonks, the policy, and—perhaps most crucially—much of the Democratic Party’s bad blood. While Politico’s Playbook notes who is spotted from

Biden’s inner circle lingering at Georgetown soirees, there’s an enlivened alternative scene in D.C. these days: a younger, rowdier crowd of White House aides, congressional staff, and activists who likely voted for Elizabeth Warren or Bernie Sanders, gathering on rooftops over cheap beer. Their candidate didn’t win—Washington belongs to Biden. But the left is taken seriously these days. And they’re having a lot more fun along the way.

THAT LEVEL OF INFLUENCE didn’t exist for progressives who were around for the last Democratic administration. (Most of the people on that Adams Morgan rooftop were not.) At its best, Barack Obama’s White House showed apathy: Phone calls went unanswered, letters unread. At worst, it was openly hostile—as when Obama press secretary Robert Gibbs, in a 2010 interview, accused the “professional left” of being so “crazy” that its members “ought to be drug tested.” A tightly managed coalition of palatable liberal organizations—such as MoveOn and the Center for American Progress—had regular meetings with White House officials in a capacity blogger Jane Hamsher dubbed “the veal pen,” a phrase borrowed from Douglas Coupland’s 1991 novel, Generation X, that describes a generation trapped in a cubicle until slaughter time.

That dynamic has changed, thanks to a pandemic and a Democratic primary that left the party in need of unifying. Not to say there isn’t still a “veal pen” in the Biden era. The leaders of D.C. progressive groups attend a meeting every other week convened by Deirdre Schifeling, a top aide in the White House’s political shop who cut her teeth in progressive organizing. In theory, it’s a place for lefties to stay in the loop on White House news. In practice, “it’s a meeting where people let off steam,” in the words of one frequent attendee.

The real measure of influence is honestto-goodness access, which these activists now have in spades. That’s due in no small part to the fact that certain activists and wonks now serve in the roles they antagonized in past administrations. That shift was on full display at a meet and greet happy hour that Adam Green, co-founder of the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, held at his home in October. Green has periodically hosted networking gatherings on his rooftop, where a regular rotation of left-flank operatives mingles with the Democratic establishment and reporters in front of a street art mural of Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez that Green had painted along

DEMOCRACY WATCH

On a scale of 1-10, how concerned are you that the U.S. will become more authoritarian over the next five years?

Sherrilyn Ifill

President of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund

Every day the Senate fails to pass voting rights legislation pushes up the number for me. I’m somewhere around 6 or 7 right now. If by the end of January we don’t have passage of new voting rights legislation, I’m at 9.

Aziz Huq

University of Chicago Law School 8—Democracy’s losing both its popular and institutional supports: Republicans are unwilling to see electoral loss as explicable or acceptable; Democrats too splintered to advance even basic reforms. Up high, a conservative Supreme Court building tools to allow the reversal of electoral results. Combined, all this leaves few reasons for optimism.

Mehdi Hasan msnbc host

11 out of 10. One of our two major parties has given up on democracy and openly embraced voter suppression, partisan gerrymandering, and election subversion. Oh, and white supremacy, too. The result? We are in the midst of a slow-moving, rolling coup while the American polity heads in the direction of authoritarianism, if not full-blown fascism.

Rachel Kleinfeld

Senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

I am concerned about harm to liberal democracy at a 9. Particularly security institutions that lean towards one party or fail to enforce laws equally, which are pernicious. Far-right protests have become more violent in the U.S. in the last year—but police interventions have gone down. Meanwhile, homicide rose almost 30%. Internationally, greater violence often leads to demands for law and order, allowing a backlash of more authoritarian laws and enforcement.

5 State of the Nation

the back wall of his patio. Many of those regulars reappeared that October evening to mix with a crew of Big Tech critics who now have key jobs in the administration, such as Rohit Chopra, director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau; Lina Khan, chair of the Federal Trade Commission; and Tim Wu, the White House’s policy adviser on technology and competition.

The Biden era has also offered progressives long-rare opportunities to celebrate victories, albeit fleeting ones. In late October, UltraViolet co-founder Shaunna Thomas and progressive angel investor Leah HuntHendrix hosted a happy hour planned on the heels of the Congressional Progressive Caucus’ momentary success in keeping the fates of the infrastructure bill and Biden’s Build Back Better bill tied together. The shindig was a celebration for Mike Darner, the CPC’s executive director. Darner, aptly described in the invitation as “quiet and humble,” had one request: Hold the happy hour soon, before progressives ran out of things to celebrate. (He would be correct, as the House voted for the infrastructure bill alone two weeks later.)

On a balmy evening, a veritable “who’s who” of the Beltway left congregated on Hunt-Hendrix’s rooftop. Representatives Mondaire Jones and Jamie Raskin made brief appearances—as did Ilhan Omar, who plopped down on a wide, cushioned patio chair next to an aide. Cori Bush wasn’t present, but a contingent of her aides were. Staffers from lefty activist groups, such as Indivisible and the Justice Democrats, caught up with leaders of progressive think tanks. Guests politely sipped wine from clear plastic cups until the gathering reached its fourth hour and supplies ran dangerously low. Around 9 p.m., someone offered me a

hard seltzer they’d quietly procured from a friend’s purse (and, like the dutiful millennial I am, I accepted).

So, are progressives having more fun in Biden’s Washington? “I don’t know if I’m having more fun,” Green said, hinting at exhaustion. “But when it comes to having impact, it is a better time to be a progressive.”

ALONGSIDE THE RISE in revelry has come newfound mainstream media attention. Some of that began after the arrival of “Squad” members such as Ocasio-Cortez and Omar. “The press is paying attention to us! I like this!” Pramila Jayapal, chair of the CPC, exclaimed at a press conference after the 2018 midterms. But often that attention devolved into the unwanted kind—an uproar over the Squad’s defense of Palestine or a kerfuffle with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. Now, “because we have power, reporting is more focused on the work we’re doing and how it relates to the administration,” said Jeremy Slevin, Omar’s communications director. “I keep hearing from reporters telling me: I just got hired to cover progressives for AP or Reuters.” But Slevin isn’t sure that all the attention has led to savvier coverage. “There’s still a deficit in understanding the left and the dynamics in the party,” he said. “Some of that was borne out in Build Back Better—I think a lot of mainstream outlets did not understand it was progressives who were defending Biden’s agenda.”

The distance between the White House and the Beltway left isn’t what it used to be, but proximity hasn’t necessarily guaranteed results. Not since LBJ’s Great Society have so many aggressively liberal ideas made their way into law, but the boldest of them—the ones that progressives helped craft and that earned Biden comparisons

to FDR—have been sold for parts in the slog of legislative sausage making. The Senate is evenly divided, and plenty of lefties serving in the administration remain skeptical. One progressive operative pointed to Biden’s principal advisers who continue to describe the soaring ambition of his domestic agenda as a middle-class tax cut. “This beautiful state-of-the-art home they built is being sold by a Realtor with a wide tie and [who] specializes in ranch houses,” the operative said.

“It’s not enough to just pass Build Back Better, we need to win the win,” said Mulholland, Data for Progress’ political director. “The White House should specify the provisions of the bill and universalize its benefits so that voters across the country know that Democrats are behind their lower childcare and electricity bills.” But when I asked her about the White House’s framing, she replied with an air of pragmatism. “The median Senate seat is 7 points to the right of the median voter,” she texted, “so it’s important to message BBB using language that works in red and purple states, too.”

D.C. is still a divided town, even among liberals. The light beer–drinking twenty- and thirtysomethings who packed onto that Adams Morgan rooftop aren’t on the invite lists for “This Town” festivities in Georgetown, where the elite, regardless of ideology, find common ground. I asked McElwee whether he’d ever been to Café Milano, the longtime power broker restaurant that transitioned over the past year from a Trump-era hot spot of Ivanka and Jared into one where you are now likely to spot White House chief of staff Ron Klain. “I’m not sure,” McElwee replied, with an air of confusion suggesting he lacked the context to know what the question was really asking.

Kara Voght is a reporter at Rolling Stone

January-February 2022 6

STATE OF THE NATION

SPOT THE FAKE RIGHT-WING BOOK TITLE

HOW THE CULTURAL LEFT HAS INFILTRATED OUR GRADE SCHOOLS

Answer: Wokehold AARON H. CONROW

In the Pipeline

Joe Biden wants to remove lead from drinking water. But can an infusion of money save Benton Harbor, Michigan?

By Derek Robertson

Illustration by Sébastien Thibault

WHEN THE NEW YORK TIMES tweeted its first story in October about the elevated levels of lead in the drinking water of Benton Harbor, Michigan, it noted the similarities to “nearby Flint.” It was a typical bit of the publication’s coastal myopia: Benton Harbor is about as far from Flint as the Times’ offices are from Providence, Rhode Island. But it’s hard to blame the paper for the geographic error, considering it’s not a categorical one.

Both Benton Harbor and Flint are majorityBlack, postindustrial Michigan cities where decades of divestment, neglect, and institutional decay led to public health crises. In early October, state officials told Benton Harbor residents to use bottled water for drinking, brushing teeth, cooking, and making baby formula, out of “an abundance of caution.”

It seems like a rerun of Flint, as Benton Harbor’s poorest residents’ lives are

upended by a practically medieval issue. But where the Flint saga was a dramatic, prefab morality tale that featured outsize characters, moments of glaring symbolism, and national protest, what’s happening in Benton Harbor has been decidedly more muted. Flint was already a city synonymous with national decay, and its lead problem arose from a rash, misguided decision by a state-appointed emergency manager. Benton Harbor’s problems developed slowly over time, in a manner that’s far more common and insidious.

Its lead concerns date as far back as late 2018. Why it’s taken three years to hit the headlines and inspire major action is a bleak story about what happens when a city’s physical and civic infrastructures disintegrate simultaneously. It’s playing out in cities across the country, but especially the upper Midwest: In July, a report from the Natural Resources Defense Council revealed that the 10 states with the most lead lines per capita are mostly clustered in the region. Nearly 500,000 lines might

still be in use in Michigan; Ohio has 650,000, a lower-bound estimate. Chicago alone is estimated to have 350,000, more than any other city in America.

President Joe Biden’s $1 trillion infrastructure bill, which became law in November, makes a massive investment to fix the problem in Benton Harbor and elsewhere. The law sets aside $15 billion to replace lead pipes and service lines. An additional $10 billion could come in Biden’s Build Back Better bill, which, as of this writing, Congress is debating. If the $25 billion total comes to fruition, it’d amount to nearly half of the high-end estimate of $60 billion that activists say is necessary to replace every lead pipe in the country.

Lead is especially harmful to children and pregnant women, because it can lead to behavioral and learning issues or harm the growth of a fetus, among other complications. It can also cause “high blood pressure, joint and muscle pain, difficulty with memory or concentration, and harm to reproductive health” in adults, according to a report from the nrdc.

But federal money alone is not enough to fix lead water issues: Experts say that the more money and labor needed to replace those pipes and create a cleaner water system, the heavier of a lift it is for already-beleaguered local governments. Even eight years after the beginning of the Flint water crisis, the city is just now nearing the end of its own pipe replacement. “The funding is not just for digging up the pipes,” said Erik Olson, a director with the nrdc who has worked closely on lead issues in Michigan. “It’s also for technical help, to help the community figure out how to do it.”

For all the uproar and media attention, life in Benton Harbor, pre-infrastructure bill, was identical to what it looks like today, and what it will tomorrow, and likely for years to come. Other cities are earlier in the process of discovering their rotten infrastructure, much less pulling it out. Just as Flint taught the nation about glaring racial and structural inequalities in America’s cities, the slow start in Benton Harbor offers its own, separate lesson about the grinding, pitfall-laden process of actually resolving the tainted water issue.

IN AUTUMN 2018, roughly four years after the beginning of Flint’s crisis, officials first urged Benton Harbor residents to test their water, after eight out of 30 homes tested for lead showed elevated levels. After

7 State of the Nation

more testing showed consistently high lead content, the city handed out filters and testing kits, and introduced a corrosion control agent to the city’s water supply, meant to prevent lead from leaching out of corroding pipes and water fixtures.

When Benton Harbor’s erstwhile major employer, the appliance company Whirlpool, announced the closing of its last plant there in 2010, the financial hit to the town left the city government flat-footed. Sharpening Benton Harbor residents’ awareness of the poor civic hand they’ve been dealt is its counterpart city St. Joseph, just across the river of the same name that divides the two towns.

The two cities have roughly similar populations of just under 10,000, but the resemblance stops there: St. Joseph is

WHO SAID IT

overwhelmingly white, where Benton Harbor is Black; rich where the latter is poor; leisure-minded where the latter has to fight for its barest institutions. In his 1999 book, The Other Side of the River, which explored the divide through the lens of the 1991 drowning of a Black teenager, which many suspect was murder, journalist Alex Kotlowitz wrote, “For the people of St. Joseph, Benton Harbor is an embarrassment. It’s as if someone had taken an inner-city neighborhood … and plopped it in the middle of this otherwise picturesque landscape.”

“There’s this long history of racial segregation, redlining in the community school system, issues with segregated schools, and just a whole history of racial inequality in Benton Harbor,” Olson said. “That, compounded with just the disinvestment

Dr. Rand Paul or Dr. Spaceman?

Rand Paul, Anthony Fauci foe and Covid skeptic, is a licensed ophthalmologist. An equally bewildering fact: In the universe of 30 Rock, Chris Parnell’s Dr. Leo Spaceman is treated as a real medical authority. See if you can spot which quote comes from which “doctor.”

1. “Between my medical practice and this job, I’m pulled in every direction.”

2. “I have heard of many tragic cases of walking, talking normal children who wound up with profound mental disorders after vaccines.”

3. “I never, ever cheated. I don’t condone cheating. But I would sometimes spread misinformation. This is a great tactic. Misinformation can be very important.”

4. “I’m being unfairly targeted by a bunch of hacks and haters.”

5. “Science is whatever we want it to be.”

6. “When is modern science going to find a cure for a woman’s mouth?”

7. “I’m a physician. That means you have a right to come to my house and conscript me. It means you believe in slavery. It means that you’re going to enslave not only me, but the janitor at my hospital, the person who cleans my office, the assistants who work in my office, the nurses.”

8. “We have no way of knowing, because the powerful bread lobby keeps stopping my research.”

9. “We shouldn’t presume that a group of experts somehow knows what’s best for everyone.”

in the community by the authorities, has resulted in this really serious problem with lead contamination.”

In late October, I sat down with Kim L. Smith Oldham, a native of nearby Van Buren County. As volunteers in a cavernous warehouse unloaded pallets of bottled water, milk, and peaches to needy residents, Oldham—who has the quintessentially Midwestern combination of geniality with a total unwillingness to tolerate nonsense— discussed her work for the nonprofit Southwest Michigan Community Action Agency over the past 25 years. She described the solidarity its residents have developed, and the almost supernatural level of patience and cooperation it takes to respond to an ever-growing level of need.

“It’s still a work in progress. You’re always fine-tuning it to see if we can do it this way, better.… At the end, we all have the same goal,” Oldham said. “It takes a bigger team than just one entity.”

That need for a collective lift has been glaringly apparent in the Benton Harbor government’s inability to respond to the crisis effectively. Of the residents I spoke to who were collecting water at the smcaa warehouse, none of them could recall being contacted by the city regarding potential lead in their home; rather, they made the switch to bottled water out of the same combination of fear and mistrust that residents in Flint have described now for years, even as its own water supply has been mostly repaired.

“I wasn’t really paying attention to it until they started talking about it,” said Reginald Lewis, an older resident who wore an oxygen tube while waiting in line. “I don’t think I’ll be OK [drinking the water] for a while.”

RESTORING LEWIS AND his fellow Benton Harborites’ trust is a tall order, almost as much as the actual pipe replacement. The strength of civic institutions has been dwindling in Benton Harbor for decades. The city’s local government has both overseen its long slide into dereliction and agitated relentlessly for outside assistance.

In November, the nonprofit news outlet Bridge Michigan said that in the 14 months following the initial reports of lead, “the city, lacking enough money or staff to quickly comply, had sought extension after extension.” A state memo said the city rejected offers for assistance with public messaging; the city’s water system was already in a cycle of debt that its mayor compared to payday lending, even before the discovery of lead.

January-February 2022

STATE OF THE NATION

Answers: 1. Spaceman 2. Rand Paul 3. Paul 4. Paul 5. Spaceman 6. Spaceman 7. Paul 8. Spaceman 9.

Paul

LEFT TO RIGHT: CHIP SOMODEVILLA/GETTY; ALI GOLDSTEIN/NBCUNIVERSAL/GETTY

“To be honest, these should have been replaced years ago, and we shouldn’t even be in the position that we’re in, but we are,” Elizabeth Hertel, head of the state Department of Health and Human Services, told The New York Times in October.

Benton Harbor’s mayor, Marcus Muhammad, is the city’s first democratically elected leader since the first emergency manager was appointed by the state in 2010, a move similar to the takeover in Flint before its own water crisis. Both were meant to bring the financially derelict cities into solvency, at any cost. The extreme austerity dragged the two cities painfully into “normal governance,” but also left them even more institutionally hobbled than before in dealing with a problem that vexes even relatively flush and functional cities like Chicago. “The problem is a lot of those communities just don’t have the expertise; a lot of them don’t even know that money is available,” said the nrdc’s Olson.

With nothing but an emailed statement from Muhammad to show for several weeks of trying to reach the mayor, I decided to drop in on City Hall in person. I walked

into a modest, silent brick building tucked away just a block from Main Street, up to the second floor, where I pressed a buzzer for admittance to the office of the city manager, Ellis Mitchell. His friendly secretary knocked on his door and stepped into his office. I heard muffled voices as she explained my request, and she soon popped back out, asking again which outlet I represented. She shut the door, continued her conversation with Mitchell, and in a few moments stepped out. The city manager couldn’t speak with me after all. Nor could Mayor Muhammad, who had just happened to step out of the office.

Benton Harbor’s population has been slowly but surely dwindling since its peak in the postwar era, and the loss is palpable. The Modern Plastics plant on Empire Avenue, a hub of industrial-era middle-class culture in the city—and which employed the mother of Eric McGinnis, the Black teenager whom Alex Kotlowitz wrote about more than two decades ago—appears abandoned, covered in dead foliage as if its staff simply walked off one day. When I visited at peak commuting hour, the city’s

downtown was eerily quiet, with just a few people shuffling out of its Main Street’s low-slung, humble offices and a legal cannabis dispensary.

The city’s comparatively small size can be a curse when it comes to many issues, but it also might be a small blessing when it comes to that pipe replacement program. The city has between 3,000 and 6,000 lead service lines, compared to the nearly 30,000 that Flint has merely inspected.

Post-infrastructure bill, Benton Harbor’s government will at least have plenty more money to throw at its problems. That’s good. But the more any given place looks like Benton Harbor, the more likely it is that acquiring that money will bring into a sharp, painful relief the history of deprivation, racism, and bureaucratic haplessness that led the city to fail its citizens’ most basic needs in the first place. If there’s any lesson for the Benton Harbors-in-waiting across the United States, it’s how those problems take a hell of a lot more than a quick infusion of cash to fix.

Free? Or Not So Free?

Freedom in the 50 States is one of the most comprehensive and definitive sources on how public policies in each American state impact an individual’s economic, social, and personal freedoms.

The Cato Institute’s 2021 edition improves on the methodology for weighting and combining state and local policies to create a comprehensive index, including a new section analyzing how state responses to COVID-19 have affected freedom since the pandemic began.

Derek Robertson is a writer and contributing editor at Politico magazine.

Derek Robertson is a writer and contributing editor at Politico magazine.

READ, DOWNLOAD, AND EXPLORE THE DATA AT FREEDOMINTHE50STATES.ORG.

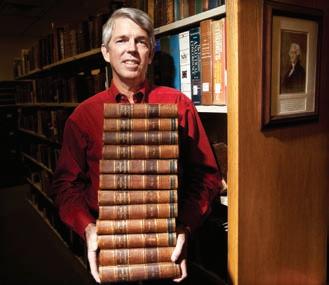

Back to Work

Under Jennifer Abruzzo, the nlrb is finally acting on what it was created to do.

By Timothy Noah

ON JANUARY 20, 2021, after President Joe Biden was sworn in on the West Front of the Capitol, and about the time Amanda Gorman finished reciting her inaugural poem, Peter Robb received an email from the new president telling him to clear out his desk by 5 p.m. This was unusual. Robb was general counsel of the National Labor Relations Board, and while incoming presidents frequently dismiss their predecessors’ appointees, they don’t typically muck around with independent agencies like the nlrb. Robb, a Trump appointee, still had about 10 months left in his term. But a statutory quirk allowed Biden to fire Robb, even though no one could remember such a thing happening before.

Presidents seldom come into office knowing what it is an nlrb general counsel does, much less who holds the job. The anodyne title belies the job’s importance. Biden, the most pro-labor president since Harry Truman, understood that whoever was nlrb general counsel would exercise tremendous power—more power, arguably, than anybody else in government—to carry out his administration’s labor policies. Clearly Robb, a management partisan who helped Ronald Reagan break the air traffic controllers’ union, had to go. Less than one month after Biden pushed Robb out, he nominated Jennifer Abruzzo to replace him. She arrived at the agency in July after a party-line Senate confirmation.

The nlrb is a quasi-judicial panel that hears cases, makes rulings, and sets binding precedents about what does and doesn’t constitute a violation of labor law (committed usually, of course, by management). The nlrb’s general counsel is effectively the agency’s prosecutor. The general counsel sets the nlrb’s agenda by choosing which cases on appeal from the agency’s 26 field offices the Washington-based board will hear. That gives Abruzzo enormous influence over what the federal government’s rules

will be about how managers in the private sector may or may not treat their workers. The general counsel also supervises those field offices, where claims of unfair labor practices are investigated and, in most instances, resolved.

Under Trump, nlrb enforcement withered. Robb settled, for a pitiful $172,000, an ambitious case brought by his Democratic predecessor that documented widespread labor violations at McDonald’s franchises in which the corporation was plainly complicit. Robb tried (unsuccessfully) to demote the regional directors en masse. Morale cratered, with surveys recording rapidly growing employee dissatisfaction. During Robb’s first two years, the nlrb staff shrank by 13 percent. This all reflected the administration’s wider anti-union agenda. Trump decried on Twitter “Dues Crazy” unions that “rip-off their membership.” He harassed federal employee unions through executive orders and weakened worker safety protections.

Biden and Abruzzo are trying to reverse as much of this as they can. Abruzzo, a Queens native from a large Roman Catholic family, worked at the agency for almost 23 years, starting as a field attorney in Miami and ending up as the deputy general counsel during the Obama administration. When I first met her five years ago at a dinner, she displayed a lively wit, but when we met again for an interview last fall at the nlrb’s offices in D.C.’s Capitol Riverfront neighborhood, she was poker-faced and all business, in the preferred style of official Washington. In an email, she later described herself as a “voracious reader and an enthusiastic elliptical rider” who typically does both simultaneously.

During Robb’s reign of terror, she joined the staff exodus. “Elections have consequences,” she told me, “and that was one of them.” Abruzzo, who’d spent the interim working as special counsel at the Communications Workers of America, pronounced herself delighted to return. “It’s my family, right?” she said. Immediately, she set about bringing the agency back to life.

In September, Abruzzo laid down a marker on the controversial question of whether college sports players are employees. In a memo, she argued they were, citing the Supreme Court’s 2020 decision in ncaa v. Alston, which expanded colleges’ ability to compensate athletes. “If by word or by deed they are led to believe they really have no rights,” Abruzzo told me, “then that’s a violation in and of itself of our statute.”

What Abruzzo called “our statute” is the Wagner Act, the 1935 law, formally known as the National Labor Relations Act, that created the nlrb and remains the principal law governing management-labor relations. Abruzzo was citing the rights all private-sector employees enjoy under the Wagner Act to form a union or engage in other “concerted” (i.e., collective) activity to improve working conditions.

Abruzzo’s memo was basically an invitation to college players and other interested parties to sue. In November, Michael Hsu of the College Basketball Players Association took her up on it. Hsu filed a complaint in the nlrb’s Indianapolis office alleging that the ncaa interfered with the exercise of college players’ right to self-organization. Whatever the administrative law judge in that region decides will surely be appealed, and Abruzzo will almost certainly bring the matter before the board to decide, a process likely to take a year or two from start to finish.

“They’re statutory employees,” Abruzzo told me. That these players receive no wages, Abruzzo said, is irrelevant under the Wagner Act. From her view, all that matters is that these workers “perform services for their university or college, and that university or college controls, or has the right to control, much of their daily lives.”

Abruzzo is also recommitting the nlrb to protecting the right of immigrants to organize regardless of their immigration status—a low priority under the Trump administration. In a November memo, she ordered nlrb officials not to collect Social Security or taxpayer identification numbers from witnesses giving affidavit testimony

January-February 2022 10

Photograph by Lexey Swall

against an employer; that these witnesses be assured no inquiry will be made into their immigration status; and that when witnesses don’t wish to enter a federal building, affidavits should be taken in a “neutral” setting.

A little-discussed provision in the Build Back Better bill, which as of this writing awaits Senate approval, would greatly expand the nlrb’s ability to penalize employers. Since its establishment, the nlrb has lacked authority to level any monetary fine beyond requiring employers to furnish back pay to dismissed workers. Consequently, employers don’t lose a lot of sleep over violating labor law (as opposed to, say, violating antidiscrimination laws, under which workers can collect substantial damages). The BBB bill would change that by allowing the nlrb to impose fines of up to $50,000 per violation, and up to $100,000 per violation if the business is a repeat offender. These fines would usually be imposed on businesses, but in egregious cases they could be imposed on individual managers as well. “Employers would certainly think twice,” Abruzzo told me, if such fines became possible.

Abruzzo noted in a September memo that the Biden board had already suggested back pay could include health care expenses; fees on credit card debt that the fired employee could no longer pay; and the cost of losing a

car or home. If an undocumented worker won a case against their former employer, Abruzzo wrote, that person could demand additional compensation if wages were depressed by the person’s immigration status. In cases where the nlrb throws out the results of a union election because the employer engaged in unfair (that is, illegal) labor practices—as, for example, the agency did regarding last spring’s vote to organize an Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama—Abruzzo said the board might want to require the employer to pick up the cost to the union of running a second election campaign. Take that, Jeff Bezos!

A Trump-era drop in caseload is partly attributable to declining union membership, but another factor, Abruzzo noted, is that during GOP administrations, workers and unions are less eager to file charges lest they risk creating anti-labor precedent. Stare decisis doesn’t cut much ice at the nlrb; precedents swing madly back and forth, depending on whether a Democrat or a Republican is in the White House.

One of the more ludicrous examples concerns whether graduate students at private universities who are paid to teach or assist research may join unions. Under President Richard Nixon, the board said yes in 1970. Then it said no, they may not, in 1972 (Nixon again). An even firmer no again in 1974

(Gerald Ford). Then, in 2000, the board said sometimes yes, sometimes no (Bill Clinton, of course). No once more in 2004 (George W. Bush). Then yes, in 2016 (Barack Obama).

The Trump board tried to kill grad student unions by issuing a regulation, but rulemakings take time, and the regulation wasn’t completed before Trump left office. So Biden scuttled it. Graduate students at Columbia, Brown, NYU, Stanford, and every other private university in the United States remain free to affiliate with unions. For now, anyway.

Perhaps, Abruzzo said, the Biden board will attempt regulations of its own to resolve such disputes on a more permanent basis, but “that takes a lot of time, and it’s resource-intensive.” It’s also outside the general counsel’s purview. For her part, Abruzzo said the Wagner Act “should be broadly construed to cover as many workers as possible.” The Wagner Act is not neutral on the question of whether the nlrb should work to increase union representation. “I think that gets lost,” Abruzzo told me. If workers “can actually engage with their employer with or without a union and actually feel like they can improve their lot in life, it’s only going to help all of us.”

11 State of the Nation

STATE OF THE NATION

Timothy Noah is a staff writer at The New Republic

DEMOCRACY’S DEFENDER

By Michael Tomasky

Photographs by Greg Kahn

How Maryland Representative Jamie Raskin became the man for this historical moment

Representative Jamie Raskin was trapped in the U.S. Capitol during the riot on January 6, 2021. He now sits on the House panel that is investigating the events that day.

By Michael Tomasky

Photographs by Greg Kahn

How Maryland Representative Jamie Raskin became the man for this historical moment

Representative Jamie Raskin was trapped in the U.S. Capitol during the riot on January 6, 2021. He now sits on the House panel that is investigating the events that day.

MOST EVERY NIGHT, just after he slips into bed, Jamie Raskin picks up a volume of the collected works of Shakespeare, thumbs through it, and reads a few pages before sleep takes him. He is not, he admits, a big reader of fiction; doesn’t have the time. But he loves his Shakespeare, he told me one October night as we sat in his kitchen. Two days later, I asked him for a quote from the Bard that sums up our times. He squinted his eyes and looked downward. ¶ “I mean, um … ‘Hell is empty and all the devils are here’?” He smiled cheekily at the line, spoken by Ariel in The Tempest, referring to sailors jumping off a burning ship; no elaboration was needed in either of our minds about who these “devils” of today might be. Then he gave the matter more serious thought. “I think about Macbeth all the time…. Lincoln was obsessed with Macbeth, and so was John Wilkes Booth, who had played Macbeth.” Contemplation of Macbeth led him to settle on his more considered answer: “I’ve thought a number of times of ‘If it were done when ’tis done, then ’twere well it were done quickly.’”

January-February 2022 14

Raskin stands in the office of Maryland Representative and House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer, where Raskin’s daughter and son-in-law took refuge during the insurrection on January 6.

The line opens Macbeth’s soliloquy toward the end of Act I, as he contemplates murdering King Duncan. The soliloquy showcases not just Macbeth’s malevolence, but his awareness that he may be setting off a series of events that he will not be able to control: “we but teach bloody instructions which, being taught, return to plague the inventor.” It is from this speech that we get the phrase “poisoned chalice,” from which the instigator of dark events will himself one day be forced to drink.

Donald Trump, who has poisoned our republic’s chalice arguably more thoroughly than any other figure in U.S. political history, has not been forced to drink from it. But then, we’re only (alas) in Act III of the Trump tragedy. The climax lies ahead. Whether Act V ends with Trump victorious, the republic in ruins around him, or with Trump vanquished and the republic saved and vindicated, remains to be seen. But if the latter, history may well note that no one—save, obviously, Joe Biden and his campaign team—did more to secure that end than Jamie Raskin.

Yes, he’s “just” a congressman, serving only his third term; in days gone by, when the Old Bulls laid their mighty girths across the House of Representatives, a third-termer like Raskin would still be an unknown, being told (probably by some segregationist) to wait his turn. But the modern Congress makes a bit more room for talent to rise to the top, and so Raskin rather quickly became a star. As a member of the Judiciary Committee, he questioned Robert Mueller; later, during the first Trump impeachment, the Ukraine one, his arguments about the Founders’ rationales for impeachment reflected his history as a constitutional law professor and scholar. It was clear then—this was late 2019—that the guy had some chops. So many members’ questions during main-event hearings are really ill-disguised speeches, delivered for editing and dropping into campaign ads; with Raskin, you could tell he was actually going somewhere. But those performances were mere prelude to the second impeachment, over the January 6 insurrection, when Speaker Nancy Pelosi put Raskin in charge. He and his team of managers are widely considered to have presented a masterful case against Trump and defense of the rule of law, and indeed, even though the Senate did not convict Trump, the vote was the most bipartisan Senate support for conviction in the country’s history.

All that unfolded just weeks after the suicide of his only son, Thomas Bloom Raskin, whose lifeless body Jamie discovered in their home on the last morning of 2020. Tommy’s death was shattering for Jamie and wife Sarah and their two daughters, Hannah and Tabitha. And it was hardly less shattering for the army of admirers Raskin, whom I first met in 2019 when I interviewed him for a documentary film, had amassed through three decades of teaching, organizing, campaigning, legislating, and handing out his business card, the one with his personal email address on it, to any constituent who approached him. To watch him make those icily logical yet passionately democratic opening and closing arguments knowing that he had recently buried his 25-year-old son—and then, the day after burying him, lived through the trauma of January 6 with daughter Tabitha and son-in-law Hank Kronick, Hannah’s husband, who both literally thought they were going to die—well, it was to witness an astonishing act not just of personal courage but of civic ardor. California Representative Adam Schiff, who chaired the Ukraine impeachment, told me that as he and Raskin walked through the Capitol’s Statuary Hall to have lunch together before the second trial, Schiff had asked how

he was holding up; he wanted to know whether the memory of his son would be a strength to him: “And he said that it would be, that Tommy loved the Constitution every bit as much as he did.”

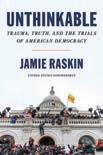

Now, Raskin is out with a book, Unthinkable, which chronicles the impeachment trial, some parts of Raskin’s background, and Tommy’s death (and his life). The congressman is, in addition to everything else, a really good writer. The blow-by-blow of January 6 is riveting (see the excerpt in this issue on page 22). The passages about his son, and his own pain, are sometimes searing: Raskin writes that he had always assumed he’d be cremated, but after they buried Tommy, he and Sarah bought the plots straddling their son’s, so he “could be buried next to [his] boy for eternity,” he explains, so “we could talk philosophy and politics and make jokes forever, starting as soon as I got there to be with him—and sooner rather than later, I hope, I remember adding darkly in my mind.”

In recent months, he has crawled out of that abyss to some extent, in no small part because he knows he has a job to do, a job his son would have wanted him to do, a job he carries on now as a prominent member of the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol. That job, put simply, is to defend the Constitution he loves, even as he grapples with its, and its authors’, many complicating downsides (not least the Electoral College, and, of course, slavery). “My mother refers to him as ‘that Constitution guy,’” Yvette Lewis, the chair of the Maryland Democratic Party, told me. I think maybe it’s not an accident that the fates saw to it that Raskin and Donald Trump were both elected to federal office on the same night in 2016: that just as certain dark forces sent to Washington democracy’s destroyer, a man who would have appalled the Founders with his dishonesty and proud ignorance and naked self-dealing, other forces sent democracy’s defender—an admirer of Thomas Paine and William James and the social movements that have pushed this country to live up to its stated principles, an utterly incorruptible public servant, the epitome of the kind of person the Founders envisioned running our government. Said Vermont Representative Peter Welch: “There’s a moral character to him. You just feel you want to be like Jamie.”

15 Features

LAMKEY/CNP/BLOOMBERG/GETTY

On February 12, during the Senate impeachment trial of former President Donald Trump, Raskin and Representative David Cicilline, a Democrat from Rhode Island, depart the U.S. Capitol.

ROD

Whether Act V ends with Trump victorious or vanquished remains to be seen. But if the latter, history may well note that few did more to secure that end than Jamie Raskin.

THERE ARE MINISTERS in Congress, and physicians and dentists and software executives and airline pilots and much else, but there is only one professor of constitutional law. So, on the morning of January 6, right after Tommy’s funeral, Jamie Raskin stepped out onto the front porch of his home in Takoma Park, Maryland, the Washington, D.C., suburb where he lives with Sarah and their two dogs, ready for work. The front porch, he writes in Unthinkable, resembled “one of those makeshift memorials on a highway to someone lost in a car accident”: flowers, letters, notes, packages, stacks of books. The trauma of his tragedy was everywhere around him. But it was January 6: an important day. He had to be there. “The public servant is there in the midst of this deepest, darkest tragedy that any family can really imagine,” marveled his friend Mark Medish, co-founder of Keep Our Republic, a nonprofit group. Tabitha tried to convince him not to go, but he said it was his duty. Deciding he shouldn’t be alone, Tabitha came along, as did his son-in-law, Hank.

Julie Tagen, Raskin’s chief of staff, drove him to the Capitol. For blocks along North Capitol Street, nothing unusual. Then, south of the New York Avenue intersection, about a dozen blocks north of the Capitol, tremors: “maga hat–wearing protesters flowing in from all directions toward the Capitol,” Raskin recalls in his book. Farther down, don’t tread on me flags, a Confederate battle flag, a woman with a sign that said fuck your feelings. They made it to the south side of the building, the House side, where the three House office buildings sit. Raskin’s office is in Rayburn. He sat down and worked on the short speech he was to give to rebut Republican challenges and argue that the election was over. Around 11:45 a.m., shortly before Trump started speaking at his rally, Raskin and Tagen headed over to the Capitol, where they were to meet Tabitha and Hank. They waited in a room numbered H-219, in the southeast corner of the building, near the House floor. It’s the Capitol “hideaway” office of the majority leader, who happens to be fellow Marylander Steny Hoyer.

Everyone knows what happened next. On a gorgeous day in October when the House was in recess, Raskin took me to the Capitol and walked me through, as nearly as could be approximated in a near-empty building, what his January 6 was like. The House chamber that you see on television is in the south side of the Capitol, on the second floor. It is surrounded by four hallways. From the vantage point of the chair looking out, on the right-hand or northern side is an entrance to the floor that is the common

reporters’ “stakeout” for Democrats, because that entrance leads to the Democratic side of the chamber. On the left-hand or southern side is the entrance that leads to the Republican seats. In the middle, in the corridor nearest the Rotunda, is another entrance; this is the one presidents use for State of the Union addresses. And opposite it, behind the chair, is a hallway called the Speaker’s Lobby—more ornate than the other halls, with three chandeliers and about 16 portraits punctuating the 80-or-so-foot-long corridor, the speaker’s office tucked in there behind the hall. At all entrances now, because some Republicans have threatened to carry their guns into the chamber, are metal detectors.

Raskin was on the floor that day. Other members who weren’t so central to the proceedings were up in the visitors gallery, which is accessed through the third floor. Before 1 o’clock, Jamie, Tabitha, and Hank were together in Hoyer’s hideaway. “Steny was really nice because he offered me this office basically like for that week, because he knew that I was being mobbed by people, reporters and stuff,” Raskin recalled. “And then he said, ‘If you’re going to bring the girls or whatever, you can use this office.’” Sometime around 1 p.m., Raskin went to the floor, and guards escorted Tabitha and Hank up to the gallery.

Right around then, two things happened. Mike Pence released his letter affirming that he would certify the count, which was the first moment that Democrats understood that the election would not be stolen; but at the same time, the first rioters breached the barricades on the Capitol’s west front, facing the mall. At 1:10, Trump finished his speech, and a much larger crowd marched toward the Capitol. A short time later, Raskin delivered his speech; some instinct told him not to utter the sentence that goes, “This is the peaceful transfer of power we celebrate and a model for a grateful world.” He sat down. Tragicomically, the next speaker was Lauren Boebert, the QAnon devotee who the people of Colorado’s 3rd Congressional District have decided belongs in the House of Representatives. At right around 2 p.m., Raskin got his first sense that something was amiss from his friend Alyssa Milano, the actress, who was watching it all unfold on television and texted him to ask if he was safe. At 2:09 came another text, this one from the Capitol Police: “All buildings within the Capitol Complex, Capitol: External Security Threat No Entry or Exit.” The text advised members to “shelter in place” and “stay away from exterior windows or doors.” Members started getting texts with photos of the rioters. Liz Cheney, to whom Raskin has grown close, recalled to me: “Jamie and I were both sitting on the aisle in the chamber, he was on the Democratic side, right on the aisle,

January-February 2022 16

and I was on the Republican side, right on the aisle. And as the reports were coming in of the mob, getting closer to the chamber, and we were being given directions about what to do, there was a moment where Jamie was looking at his phone, and he sort of looked up from his phone, and he said, ‘Oh my God, Liz.’ And I said, ‘What is it?’ And he said, ‘There’s a Confederate flag flying inside the Capitol.’”

Tabitha and Hank had been up in the gallery, but at some point they left. Abigail Spanberger, the Democratic congresswoman from Virginia, remembers a moment when Raskin looked up for them and didn’t see them. “The look on his face as they were trying to contend with what was happening on the floor, and it wasn’t immediately apparent where his daughter was, was pretty extraordinary,” she told me. Raskin called Tagen, and she said she was with Tabitha and Hank in H-219. On that October day, Raskin showed me the room—the three locks on the door, the chair they slid in front of the door as they listened to the chaos, screaming, and a few gunshots just on the other side of it (this is also very near where the QAnon-believing rioter Ashli Babbitt

was shot, at the entrance to the Speaker’s Lobby). The windows look out on the west front, so they had a skybox seat from which to observe the hundreds of rioters storming the Capitol.

The three of them stayed in H-219, a room I’d say is about 10 by 20 feet or so, for around three hours, with no food and only some orange juice from Hoyer’s small refrigerator. Once the rioters were dispersed, members were led in large groups down to the basement and eventually back to the House office buildings. The experience was terrifying. “Nobody took out an AR-15 and started mowing everybody down, but that’s what everybody was thinking was going to happen,” Raskin said. And beyond being terrifying, it was horrifying. After he was reunited with Tabitha, Hank, and Julie, Raskin went on c-span to assure the country that the certification would continue, but he stopped to note what a hideous moment this was: “Attacks on the Capitol didn’t even happen during the Civil War. You have to go back to the War of 1812 to find something like this, and that was a foreign power that attacked us. There was no Confederate attack on the Congress. So we’re going to complete the count if we have to stay

17 Features

The Rotunda was among the parts of the U.S. Capitol through which the insurrectionists marched.

here all night or even all day tomorrow. We’re going to swear in Joe Biden and Kamala Harris on January 20th. This violence is intolerable, lawless, and unacceptable, so we have to finish the job we were sent to do.”

IF RASKIN TOOK JANUARY 6 a little more personally than most members, it was partly because of his respect for our democratic customs—and partly because the nation’s capital is his hometown. He was born in 1962 in George Washington University Hospital; his Takoma Park home is less than 10 miles away. (His full name is Jamin Ben Raskin; his parents named him after his paternal grandfather Benjamin, who’d been a plumber, playfully reordering the syllables of the first name.) “My dad used to say that everybody wants to fly like a bird or just stand like a tree, and some people are bird people, and some people are tree people,” he said. “I’ve always been a tree person.”

The dad in question was Marcus Raskin, a formidable intellectual who would go on to help found the Institute for Policy Studies, which at its peak was Washington’s top left-leaning think tank. At the time of Jamie’s birth, he was on staff at Kennedy’s National Security Council. “His first day of work was the Bay of Pigs,” Raskin recalled. His mother, Barbara, was a journalist and novelist; her most successful novel, Hot Flashes, spent five months on The New York Times’ bestseller list. His maternal grandfather, Samuel Bellman, was the first Jewish person elected to the Minnesota state legislature (from the St. Louis Park area, famed as the home of Al Franken, Norm Ornstein, Thomas Friedman, and the Coen brothers).

Jamie Raskin grew up in the Adams Morgan neighborhood of D.C., in a house full of politics, books, art, intellectual thrusting and parrying. Dr. Benjamin Spock popped around, and George McGovern and Ralph Nader. As if that weren’t enough, Marcus was also a concert-level pianist. “He taught Philip Glass how to play the piano, which a lot of people say explains everything you need to know about Philip Glass,” Raskin joked.

In 1968, during the Vietnam War, Marcus, who died in 2017, was indicted along with Spock and others for illegally counseling young men to evade the draft. He was acquitted, but the indictment played “a defining a role in the formation of my political consciousness,” Raskin said. It was a time of turmoil in Washington. Jamie was one of two white students in his public school class, and things got a little dicey at school for him after the 1968 riots, so his parents moved him against his wishes to Georgetown Day School, founded in the 1940s as the district’s first integrated school. He went off to Harvard when he was just 16. He laughed: “That was a form of subtle child abuse to get rid of me. When I got there, everybody was off getting drunk and losing their virginity. And I was looking for the chess club with my Star Wars lunch box.”

After Harvard Law and a short stint as an assistant attorney general in Massachusetts, he decided he wanted to teach, and, lo and behold, he landed a job at the American University Washington College of Law in the very town in which he grew up, where he taught until he joined Congress. Sarah eventually became a staffer on the Senate Banking Committee. Hannah was born, then Tommy, then Tabitha. Meanwhile, Jamie was involved in politics both national and local. (Takoma Park is an affectionate punch line on the left, akin to the People’s Republic of Santa Monica.) They were a close, loving family (“My sister says that the Raskins say ‘I

love you’ when they call 411,” he told me) living a great life. Then suddenly, in early middle age, Raskin decided to enter politics. “I didn’t have any kind of grand plan, and I wasn’t sure I wanted to do it, but when the moment presented itself, I knew it was the right thing for me to do,” he told me.

The moment took the form of a seat in the Maryland state Senate. He decided to challenge a longtime incumbent, Ida Ruben, who had been wobbly on opposition to the Iraq War. It was 2005; the race was the next year. Montgomery County today is as liberal as the Upper West Side. But it wasn’t like that then. From 1987 to 2003, the county was represented in Congress by a moderate Republican, Connie Morella. David Moon, who was Raskin’s campaign manager, recalls that the campaign took a poll, “and I remember the poll results came back, and it was like 50–50 on the death penalty, 50–50 on the ICC, a controversial highway project.” That argued for caution. But Raskin, said Moon, “was like, no, that doesn’t make sense to me. That doesn’t make sense for how we’re going to win, or why I’m gonna run.” He was the underdog. Ruben outspent him two-to-one. He won by two-toone. “He has a touch,” said Hans Riemer, a Montgomery County Council member. “He makes people feel great, and you could see in his candidacy, he exudes enthusiasm and optimism and love and excitement.”

His friend Brian Frosh recalled that when Raskin joined him on the state Senate’s Judicial Proceedings Committee, landmark bills on marriage equality and gun safety were passed—measures Frosh said he couldn’t get through until Raskin joined the fight. Raskin did two other big things as a state senator. First, his constituent work was ferocious. Takoma Park Mayor Kate Stewart said that Raskin can remember where her children go to college and what they’re studying. Second, he made it a point to groom diverse successors. Moon, now a state legislator, is Asian American. Ditto Susan Lee, now in the state Senate. And state Senator Will Smith, who is Black, holds Raskin’s old seat. Aside from the legislation, Smith told me, “For the district and for the county, his legacy, if you look at [District] 20 now, it’s the most diverse legislative delegation

January-February 2022 18

Raskin and his wife, Sarah, live in Takoma Park, Maryland.

In the hearings for Trump’s second impeachment, to watch Raskin make his icily logical yet passionately democratic opening and closing arguments was to witness an astonishing act not just of personal courage but of civic ardor.

in the county.” And Lee told me that Raskin fought hard against Trump-era policies that cost some Americans of Chinese descent their jobs in the stem sector and held a hearing on the matter.

In 2015, Chris Van Hollen, the Democratic representative for Maryland’s 8th Congressional District, called Raskin to let him know he would be running for Senate. Raskin decided on the spot to run for Van Hollen’s seat: “I said, ‘Not only do I support you, Chris, I’ll run for your seat.’ And that was my full deliberative process.” Again, he was the underdog in a crowded Democratic primary. The favorite was Kathleen Matthews, a well-known and well-liked local TV newsperson, and wife of then-Hardball host Chris Matthews. There was also David Trone, a liquor store magnate who spent millions, and six other candidates. I remember thinking at the time that, because of Matthews’s notoriety and Trone’s money, Raskin might finish third. He got 34 percent to Trone’s 27 and Matthews’s 24. He cruised to victory in the general, but it was of course a bittersweet moment, because Trump won: “It could have been one of the most enjoyable nights of my life, but it became a really despondent night.”

The first two years, in the minority, were tough. But after the Democrats took the House in 2018, Raskin got a subcommittee chair right in his wheelhouse, the Subcommittee on Civil Rights and Civil Liberties of the House Oversight and Reform Committee. The presidential election came; Biden won it, and all of Trump’s despicable-but-hapless legal maneuvering failed. On December 15, the electors met and validated Biden’s win. As 2020 drew to a close, Raskin had many reasons to feel optimistic. On the night of December 30, it was just him and Tommy at home. They watched an episode of Family Guy. Tommy decided to turn in early, so Jamie hugged and kissed his son good night, and told him he loved him.

TELL ME, I finally worked up the gumption to say at our fourth meeting, about Tommy. It was a glorious fall Saturday afternoon. He had just finished speaking and glad-handing at an outdoor event in Friendship Heights, a posh-ish Maryland neighborhood right on the district line. We walked down the street to an Italian restaurant I like. It was around 3:30, so not crowded; some of the outside tables were occupied, but Jamie and I were the only people in the inside dining room. I ordered some brussels sprouts. Jamie—like his son, a vegan, but, unlike his son, a vegan who occasionally sneaks some goat cheese—stuck with orange juice, his go-to beverage.

He took about 30 seconds to gather his thoughts. “Tommy,” he said, “was someone whose thoughts and feelings were literally too good for the world as it is.” Most of us, he explained, can read about the war in Yemen or the famine in Sudan and feel it for a few moments and then go on with our day. “That’s not what Tommy was like,” Raskin said. “These things stayed with him.”

At the same time, Tommy was both brilliant (he was in his second year at Harvard Law) and funny. He made everyone laugh. He loved Sacha Baron Cohen, especially Da Ali G Show—on which, as fate would have it, Marcus Raskin once appeared, making his grandson proud, because he cottoned on to the hoax of it quickly. He wrote poetry, long poems, which he could recite by memory over up to half an hour, his father said. He was repulsed by the slaughter of animals, which he believed inured us to violence more generally; this is the topic of one of his poems of which his father is most proud, called “Where War Begins.” He was intellectually restless. In the book, Raskin tells the story of a time when Sarah and Tommy were driving from Maryland to Boston while Tommy was in college. Around Baltimore, Tommy finished reading an academic’s article to which he objected, concerning animal rights. He emailed the professor to challenge him to a debate. The professor emailed right back, saying he wouldn’t debate anyone who wasn’t published in a peer-reviewed journal. Tommy asked his mother what a peer-reviewed journal was. Still in the car, he wrote an essay, submitted it to various online peer-reviewed journals, got it accepted by one, and scheduled a debate with the professor. But it was around that time, in his early twenties, that depression started to consume him.

In the book, Raskin calls Tommy his “intellectual soul mate,” and he reflects, as any parent would, on what more he could have done. He told me at the restaurant: “He had said to me, maybe just a few weeks before, that he didn’t know if he could ever be happy. And I immediately started talking too fast and saying, ‘When you’re happy, you can’t imagine being sad. When you’re sad, you can’t imagine being happy. When you’re healthy, you can’t imagine being sick. When you’re sick, you can’t imagine being healthy; that this is just a passing thing and so on.’ And it was a lot of words. And I think he just looked at me, and when I look back on it now, I think maybe he had already made up his mind.” Tommy left a note, which the police found: “Please forgive me. My illness won today. Look after each other, the animals, and the global poor for me. All my love, Tommy.”

Raskin paused. He was close to tears. I asked about his daughters. He started telling me about them; a couple of minutes later,

19 Features

These next three years will test our democracy in ways it hasn’t been tested since the 1860s, or maybe ever.

as if on cue, Hannah, who now lives in Nevada with husband Hank, called. He perked up, told her he loved her, and turned back to our conversation. “It’s been hard for the girls,” he said. “And hard for all of Tommy’s cousins. If something happens like this, you’re so drowning in despair and agony that you become very self-referential. And as I’ve been able to catch my breath a little bit, it’s only now that I’ve begun to recognize how devastating it was for everybody else.”

He paused again, and stared down at the table. Again, he was holding back tears. I felt like one of those awful television reporters who holds a vigil on the front lawn of the home of grieving parents, waiting for them to step outside for the newspaper so they can ask them how they feel. Frank Sinatra’s indifferent rendition of “For Once in My Life” oozed out over the sound system. I apologized and suggested we change the subject. He stared down at the table again and whispered: “There is no other subject.”

EARLIER THAT DAY, at the Friendship Heights event, I observed roughly the ten-thousandth person come up to him in my presence to thank him, and I mean really thank him, for what he’s doing for democracy and tell him how proud they are to be his constituent. And I said to him: You know, Jamie, I notice that no one ever comes up to you to complain about their Social Security or gripe about potholes. Well, he instantly replied, that’s because I have such a great district staff, led by Kathleen Connor, whom I must insist you speak to (I did, and she’s great; she’s known Raskin since her son Jack and Tommy were in kindergarten together). I said, I’m sure that’s true. But somehow I don’t think that’s really the reason.

These next three years will test our democracy in ways it hasn’t been tested since the 1860s, or maybe ever. The scenario is pretty straightforward. The Republicans retake the House in the midterms. Immediately, any chance of Biden passing meaningful legislation is dead, but that’s the least of it. The GOP will launch hearing after hearing, issue subpoena after subpoena; they will find some flimsy rationale on which to impeach Biden, and they will stretch it out as long as possible. Trump will run—as Raskin put it, “for psychological, political, and financial reasons”—and he will be the GOP nominee, Raskin has little doubt. Assuming Biden seeks reelection, the election will probably be close, because elections just are these days. If Biden wins by a matter of several thousand votes in a few states, as he did in 2020, the Trump machinery will kick into gear to steal the election. Republican election commissioners and state legislators and even some governors will put forward pro-Trump electors. The House of Representatives will not vote to certify Biden’s win in

January 2025, which will toss the election to the House, which will make Trump president. (When a presidential election gets thrown to the House, under the Twelfth Amendment, the vote is by state delegation, so North Dakota has the same voting power as California; Republicans now control, and will likely in 2025 still control, a majority of state delegations, and Liz Cheney will probably be gone, meaning that Wyoming will go pro-Trump.) For the second time in the history of the United States, the other time being 1824, Congress will have installed as the president a candidate who did not win a plurality of votes in either the Electoral College or the popular vote.

“Donald Trump has now converted every formerly ministerial step of the process into a moment for partisan rumble and contest,” Raskin told me. “So when we’re talking about the certification of the state popular vote, the governors’ certification of the electors, the electors meeting, and then the January 6th joint session receipt of the electors … all these phases of the process have now been turned into yet another opportunity for partisan combat.” There is no question in Raskin’s mind that this is what Trump and his supporters will try to do.

The select committee on January 6 ties in directly here. Aside from trying to get to the bottom of who did what before and on the infamous date, Raskin wants the committee to try to take steps to safeguard democracy from attack by Trump or any future Trump wannabe. “Our select committee, I believe, should do whatever it can to reform the Electoral Count Act, to make it conform as much as possible to the popular will,” he said, referring to the 1887 act that spells out—confusingly, ambiguously, contradictorily—the presidential election certification process.

That obviously won’t be possible if Republicans retake the House. In the majority, the GOP will likely do all it can to subvert democracy and preemptively make people distrust the electoral process. In that case, Raskin will become an even more important voice in the Democratic Party than he is now. As his friend Representative Don Beyer of Virginia put it: “I think we all recognize that the most eminent constitutional scholar in the Congress is Jamie.”

Toward the end of my reporting for this story, I contacted four scholars to ask them if they knew of a quote from James Madison or Thomas Jefferson—Raskin’s favorite Founders, after Thomas Paine—that summed up Jamie Raskin. Jeffrey Rosen, who runs the National Constitution Center, invoked Federalist 57, perhaps written by Madison: “The aim of every political constitution is, or ought to be, first to obtain for rulers men who possess most wisdom to discern, and most virtue to pursue, the common good of the society.” Raskin, Rosen emailed me, “is exactly the kind of representative Madison had in mind, one governed by reason rather than passion, and devoted to the public good rather than to partisan interests.”

January-February 2022 20

William Antholis, a political scientist who heads the Miller Center at the University of Virginia, quoted from a letter Jefferson wrote in 1822 to William T. Barry: “Very many and very meritorious were the worthy patriots who assisted in bringing back our government to its republican tack. To preserve it in that will require unremitting vigilance.” Nancy Isenberg, on behalf of herself and husband and co-author Andrew Burstein, suggested a short Madison essay that ends: “Those are the real friends to the Union, who are friends to that republican policy throughout, which is the only cement for the Union of a republican people; in opposition to a spirit of usurpation and monarchy.” And Princeton historian Sean Wilentz told me: “Jamie Raskin approaches leadership in a spirit that Jefferson and Madison spoke of as ‘liberality,’ unswerving in principle but undogmatic, broad-minded, humane in the exact sense. In his resistance to doctrine as well as his intellect, no one today comes

closer than Jamie does to the revolutionary generation’s ideal of a public servant.”

Raskin is an admirer of the American pragmatist school of philosophical thought. Pragmatism, he told me, “is essentially democratic political experimentation for the common good. That to me is the promise of democratic politics—developing projects to try to make life better for people and transform the human condition.” He concludes Unthinkable with a meditation on this through Tommy’s eyes, a meditation that reveals that the book’s title doesn’t refer solely to what happened on January 6: “Tommy Raskin dared to think the unthinkable also when it came to transforming the human condition…. He dared to think about not only what was unthinkably dreadful in the human experience but also what might be unthinkably beautiful in our potential future….” It’s a very Raskinesque sentiment: that the unthinkable can also be good.

21 Features

Raskin stands outside the U.S. Capitol, on the side of the building occupied by the House of Representatives.