Article

What’sviolencegotto dowithit?Inequality, punishment,andstate failureinUSpoliticsLisaLMiller RutgersUniversity

Punishment&Society

2015,Vol.17(2)184–210

! TheAuthor(s)2015

Reprintsandpermissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI:10.1177/1462474515577153 pun.sagepub.com

Abstract

ThispaperoffersareframingofthedynamicsofcrimeandpunishmentintheUnited Statesbyexploringlethalviolenceandsituatingbothviolenceandpunishmentwithin thelargercapacityoftheUSpoliticalsystemtoshieldcitizensfromarangeofsocial risks.Iarguethatsecurityfromviolenceisanimportantstateobligationandthen illustratetheexceptionallyhighratesoflethalviolenceintheUS,relativetoother richdemocracies,andtheirclusteringwitharangeofotherracializedsocialrisks, includingpovertyandimprisonment.Ithenprovideaframeworkforunderstanding theexceptionalstatusoftheUSbyexploringthefragmented,racializedandlegalistic institutionsofAmericanpoliticsandtheroletheyplayinproducingarangeofsocioeconomicinsecurities.IarguethatbothviolenceandpunishmentintheUScanbeseen aslimitedformsofstatefailure,particularlywithrespecttoAfrican-Americans.

Keywords

violence,punishment,inequality,race,institutions,statefailure

Introduction

FewpathologiesoftheUSstatehavegarneredasmuchscholarlyattentionin recentyearsasUSexceptionalisminimprisonment(e.g.Barker,2009;Campbell andSchoenfeld,2013;Garland,2001;Gottschalk,2006;Simon,2014;Western, 2006).TheUnitedStatesistheworldleaderinincarceration,withovertwomillion peopleinfederalorstatejailsandprisons–roughlyonein108Americans

Correspondingauthor:

LisaLMiller,DepartmentofPoliticalScience,RutgersUniversity,89GeorgeStreet,NewBrunswick, NJ08901,USA.

Email:miller@polisci.rutgers.edu

(GlazeandHerberman,2013).Equallytroublingistheracialdisproportionalityin confinementanditslong-termconsequencesforindividuals,families,andcommunities,particularlyAfrican-Americans(e.g.Clear,2007;Western,2006).

Whilethemassimprisonmentliteraturehasprovidedvaluableinsightsintothe causesofthesedevelopments,toalargeextentarrestandincarcerationhavecolonizedthescholarlyagendaonthepoliticsofcrimeandpunishment(e.g. Gottschalk,2006;LermanandWeaver,2014;Tonry,2009;Western,2006).Asa consequence,wehaveamuchmorelimitedunderstandingoftheoriginsandconsequencesoftheflipsideofUSover-punishment,thatis,USunder-security.1 While mostpunishmentstudiesbeginwithvariationinratesofimprisonment,Ibegin withviolentvictimizationandarguethattheUSstate’swillingnesstoover-punish lawbreakersreflectsitslimitedandracializedcapacitytosecurethecitizenryfrom violenceandotherformsofsocialrisk.

Re-centeringseriouscrimeinthepoliticsofpunishmentliteraturerenders visibletheexceptionalnatureoftheUS,notonlyinimprisonment,butalsoin lethalviolenceandarangeofsocio-economicrisks.Expandingthelensbeyond massimprisonmentthusrevealsastarkclusterofpersistent,andinsomecases, worseningsocialinequalitiesthatarestratifiedbyraceandclass.Considering violenceinthiscontextexposesbothviolence and punishmentasformsoflimited and racializedstatefailure thatleaveasubstantialportionoftheUSpopulation athighlevelsofsocialrisk, including,butnotlimitedto,imprisonment.These multiplerisksarefeltmostacutelybythepoorgenerally,andAfrican-Americans specifically.

Iexplainthisstatefailurethroughtwointer-relatedaspectsofUSexceptionalismthatarelong-standingbutbecameparticularlyossifiedinthesecondhalfof the20thcentury:thechallengeofproducingpublicgoodsowingtothefragmentedandracializednatureofUSpoliticalinstitutions;andthecultureof legalismthathaspushedpoliticalmobilizationonimprisonmentintochallenges tostatecriminallaw,procedureandpractice.BothaspectsofUSpoliticshave longobscuredpersistentraceandclassdisparitiesinexposuretoviolenceand othersocialrisks,butimportantchangesinpoliticalfragmentationafterthe SecondWorldWar–suchasthegrowthofsocialissuesonthenationalpolitical agenda,theprofessionalizationofstatelegislatures,prisonsandlocallaw enforcement,andtherapidretreatfrombroadsocialpolicymakingafterthe 1960s–collidedwithawaveofviolentcrimetoproducedistinctivesocial outcomes.

Thearticlebeginsbydiscussingtheimportanceofsecurityfromviolenceasa socialgoodanditsrelationshiptoageneralunderstandingoffailedstates.Isuggest that,despitethefactthatsecurityfromviolenceisacentralstatefunction,thereisa yawninggapinthepunishmentliteraturetheorizingitsrelationshiptootherstate obligations,andtopunishment.Drawingoncomparativehomiciderates,Ithen illustratehowhomicideintheUnitedStatesinthesecondhalfofthe20thcentury was strikinglyhigher,rosemoredramatically,lingeredfarlonger,andwasmorepervasiveacrosspopulations thantheliteraturegenerallyacknowledges.Ratherthan

relyingsolelyonmurderratesper100,000,Ialsoprovideaheuristicformurderrisk overalifetime,andthediffusionofmurderacrossdemographicgroupsinorderto highlighttheexceptionalandubiquitousnatureofUSlethalviolence.

Fromthere,Ileveragecomparativepoliticaleconomy/institutionsframeworks (perLacey,2008)tobetterunderstandtheUScasebyobserving aclusterofsocial risks,exposuretowhichisremarkablyconsistentacrossnationalpoliticaleconomies.Suchexposure,Iargue,canconditionthepoliticaldynamicsofpunishmentin importantways.IthenlocatethedisproportionateclusterofrisksintheUSinthe contextofthelong-standingfragmented,legalisticandracializedinstitutionsofUS politicsthatcontributetodeepeconomiccleavagesacrossracialgroups,aswellas highlevelsofsocialinequality,crimeandpunishmentrelativetootherdeveloped democracies.

Iconcludebysuggestingthatsituatingcrimeandpunishmentstudiesmore squarelyinthearenaofstatecapacitytosecurethecitizenryfromarangeof risks,includingbothviolenceandrepression,highlightsthebroaderincapacities andracializednatureoftheUSpoliticalsysteminthepost-warperiod.Whileitis temptingtoseetheriseofmassimprisonmentinthelastfewdecadesofthe20th centuryasmuscularstatecapacity,Iarguethatitismoreproductivelythoughtof asreflectingthechallengesthatinhereintheUSpoliticalsystemtotheproduction ofcollectivesecurities,particularlywhenpolicyisaimedatexpandingsecurityto African-Americans.Suchinsecurities,includingexposuretoviolence,thenproduce politicalpressuresthatarefilteredthroughthesamefragmentedandracialized institutionalmechanismsthatcontributetohighinequalityandracialstratification inthefirstplace.Theresultisastrongsetofincentivestorespondtogrowingrisk ofviolenceinoneofthefewarenaswherestatecapacityismostvisiblyandeasily increased:policeandprisons.

Whyfocusonviolence?

ThelackofsystematictheorizationabouttheroleofseriousviolentcrimeinUS exceptionalisminimprisonmentispuzzling(butseeZimringandHawkins,1997 andLaFree2002).Securityfromviolenceisabasichumanneed,alegitimatestate interest,andacorepublicgood.Socialtheorists–fromHobbestoWebertoRawls –havelongrecognizedthatacoresourceofstatelegitimacyisitsabilitytoprotect theindividualswhoconstitutethebodypoliticfrombothinternalandexternal threat(Hobbes,1962;Rawls,1971;Weber,2004).2 Highlevelsofseriousviolence raisequestionsabouttheauthorityandlegitimacyofthestateandthepossibilityof statefailure.Statefailure,generally,canbeunderstoodas:

Thecompleteor partialcollapseofstateauthority... Failedstateshavegovernments with littlepoliticalauthorityorabilitytoimposetheruleoflaw.Theyareusually associatedwith widespreadcrime,violentconflicts,orseverehumanitariancrises and theymaythreatenthestabilityofneighboringcountries.(KingandZeng,2001:653, emphasesadded).

Whilethetermisassociatedwithhighlyunstablepoliticalsystemsandisrarely appliedtodevelopeddemocracies,itnonethelessresonateswithspecificsegments oftheUSsocio-economic,legalandpoliticallandscape.AsIwillillustratebelow, relativetootherdevelopeddemocracies,violentcrimeintheUSisexceptionally highandhomicideratesforsomegroups–young,blackmales,specifically–parallelthoseofsomeofthemoremurderouscountriesintheworld.Thelimited capacityofthepolicetoimposetheruleoflawinsomeurbanareasandthe weakpoliticalauthorityofthestatemoregenerallyinsuchcontexts,isalsowell documented(Anderson,1999;Goffman,2014).Inaddition,recentworkonthe dramaticallydifferentlivingconditionsforAfrican-Americansandwhitesinthe mostpopulatedcitiesinthecountryrevealssocio-economic,crimeandhealthconditionsforsomeblackneighborhoodsthatcanbecharacterized,withouthyperbole,asa crisis(MasseyandDenton,1993).TheanalysisofurbanneighborhoodsbyPeterson andKrivo(2010),forexample,foundthattheresimplyarenomajoritywhiteneighborhoodsthatarecomparabletomajorityblackneighborhoods,withrespecttorates ofviolentcrime,unemployment,poverty,andconcentrateddisadvantage.

Thisgapintheorizingtherelationshipbetweenviolence,socialinequalities,and punishmentrisksmisrepresentingthenatureoftheUSstateandthepoliticsof punishmentinseveralrespects.First,itlargelyisolatespunishmentfromarealand horrificsocialrisk.Paradoxically,someoftheearliestworkontheriseofincarcerationandothershiftsincriminaljusticeinthelate20thcenturyhighlightedthe centralityofsustainedhighratesofcrimeforsuchanalyses.Notably,David Garland,inaseriesofworks(1996,2001),regardedhighcrimeasacentralfeature ofthecurrentsocio-politicaldimensionsofpunishment,notintermsofaone-toonecausalrelationship,but,rather,asacontextthatbothconditionsandreflects thepossibilitiesandcapacitiesforgoverning.Strangely,scholarshavelargelyneglectedthisparticularfeatureofGarland’swork,focusinginsteadonthechangesto thestateapparatus,modesofgovernance,andpublicandprivatesectoraccommodationstolatemodernity.3

Inadditiontothetheoreticalreasonstotreatviolenceasarealsocialrisk,an ampleliteratureinpublicpolicydemonstratesthatwhendestabilizingsocialconditionsarise,suchasunemploymentordeadlydisease,thepublicislikelyto becomeacutelyawareofthem(BaumgartnerandJones,1993;Kingdon,1984). Studiesofcomparativewelfarestates,forexample,havefoundthatrealeconomic insecurityandaworseningeconomyinducegeneralpublicanxietyandsuchgrowingriskshaveveryrealpoliticalresponsesthatvaryacrossdifferentlyconstituted democraticsystems(BermeoandPontusson,2012;ManzaandBrooks,2007; Rehm,2011).

Analysesofcrimeandpunishment,however,haveyettoembracethisunderstandingoftherelationshipbetweengrowingriskofviolence,politicalinstitutions andoutcomes.Whilelethalviolenceinmoderndemocraciesaffectsonlyasmall portionofthepopulation,highlevelsofothersocialinsecurities,suchasunemploymentorglobalpandemics,alsotouchonlyafractionofthepublic.Yettheyare typicallystudiedascrisesfortheirpoliticalconsequences,especiallywhenthereare

suddenanddramaticincreases,orpersistenceoveranextendedperiodoftime.

Anxietyovertheriskofseriouspredatoryviolenceisrarelygivensuchquarter.As aresult,ourunderstandingofimprisonmenthasbecomelargelyuntetheredfrom relativelevelsofmaterialriskacrossdemocraticsystemsandovertime. Reintegratingseriouscriminalviolenceintoanalysesofpunishmentprovidesthe opportunitytothinkmoresystematicallyaboutstatecapacitytosecurethecitizenrynotonlyfromrepressivepractices,butfromotherformsofriskaswell.

Second,andrelatedly,neglectingviolenceobscuresdeepsocio-economicand racialdisparitiesintheexperienceofviolence,andtreatspopulationssuffering fromhighriskasmere objects ofsocialpolicy,renderinginvisibletheirpolitical agencyandrealinterestingreatersecurity.Whilescholarlyworkhasrightly observedthedisproportionateuseofimprisonmentforthepoorandminorities, theneglectofviolencehasoverlookedthedailythreattothesesameindividuals, familiesandcommunitiesthatrealviolenceimposes(butseeForman,2012; Fortner,2013;Kleiman,2010;Miller,2010).

Finally,neglectingviolencehasledtoanover-relianceontheUScaseasabasis fortheoreticallyandempiricallygeneralizableclaimsaboutthesocio-political dynamicsofpunishment.ConsideringviolenceintheUSmoresystematically,by understandingitspersistence,diffusionandseverity,alongsideotherformsofsocial risk,reframesthecomparativeanalysesbysituatingcrimeandpunishmentwithin thedistinctivefeaturesofUSpolitics.Inotherwords,thinkingcarefullyabout violenceasasocialriskprovidesanopportunitytoconsiderhowpoliticalinstitutionsmayexacerbateormitigatesuchrisks(e.g.Lacey,2008).Moreover,itmoves usbeyondthenarrowsearchforcausalfactorsthatexplainyear-to-yearvariation inimprisonmentandtowardabroaderframeworkthatconsidershowtheexperienceofrisk,broadlyconceived,conditionsthepoliticsofpunishmentindifferent democraticpoliticalsystems.

Iarguethatpersistentlyhighratesoflife-threateningviolencealongsidehigh levelsofotherformsofsocialinequalityprovideanimportantcontextforthe politicsofpunishmentinthreeimportantways.First,ahighriskofviolence mayerodepublicconfidenceinthecapacityofthestatetosecurethecitizenry andincreasesocialcohesion,muchasitdoesinfailedstates(seeGarland,2001; LaFree,2002;Roth,2009;ZimringandJohnson,2006forarelateddiscussion). ConsistentwithBarker(2009),suchweakenedpoliticalauthoritymayincrease demandsforretribution,evenfromthosewhomightotherwisebeamenableto morerestorativeoptions.Second,thesesocialconditionsmayreflectthe actual limits ofsocio-politicalinstitutionsandeconomiesthatrenderpervasivetheconditionsthatgiverisetoviolenceandinequalityinthefirstplace.Inotherwords, relativelyhighratesofmurderandothersocialinequalitiescreateapolicycontext inwhichthepublic–withgoodreason–lacksconfidenceinthecapacityorwillingnessofthestatetoamelioratetheircauses.Highlevelsofviolenceandpunishmentwouldbothreflectandreinforcethelimitedpoliticalopportunitiesfor reducingthem.Similarly,lowratesofviolenceandinequalitymayposelessofa threattothecredibilityofthestatetoreturntoitsmoresecurenorm.

Suchconditioningofthepoliticalprocessbyrealratesofviolenceandinequality arefurtherlikelytobefilteredthroughraceandclassprejudices,wherepopulations thatsufferfromhighratesofbothmaybeseenasincapableofbeingintegratedinto themainstream.

Finally,whereinequalityacrossriskexposureispersistentlyandhighlyracialized,asitisintheUnitedStates–where,forexample,homicideratesforblacks sometimesexceedsthatofwhitesbyanorderofmagnitudeandwherethe unemploymentrateforwhitesclimbedpast8percentonlyfourtimesbetween 1975and2010(1982–1983and2009–2010)whiletheblackunemploymentrate has remained over8percenteveryyearbutoneduringthesametimeperiod (2000)–socio-politicalanalysisshouldconsiderwhetherandhowsuchconditions constituteafullorpartial racialized failureofthelegitimacyandauthorityofthe state.Theorizingviolencenotsimplyasanisolatedpotentialpredictorofvariationinpunishmentratesbut,rather,asapotentialcrisisthatclusterswithother risks,vulnerabilitiesandinequalitiescanincreasescholarlyunderstandingofthe politicalcapacityofdemocraticinstitutionstoinducelowlevelsoflethalviolence, distributesocialgoodsinareasonablyequitablefashion,andlimittheuseof staterepressiveapparatusinresponsetothreatsto,orbreakdownsin,thesocial order.

Abriefnoteonhomicide

Ideliberatelyfocusexclusivelyonseriousviolencehereinordertodistinguish maluminse,actsthatarethemselvesconsideredtobeharmful,suchasinterpersonalviolence,from malumprohibitum,actsthatarecollectivelydetermined tobedamagingtosociety,suchasdrugdealing.Ithinkthisdistinctioniscrucial forguidingresearchoncrimeandpunishment.Securityfrom life-threateningviolence isperhapsthemostfundamentalpublicgoodthatmembersofthebody politiccanexpectthestatetoprovide,andhomicideisparticularlycrucialinthe existentialthreatitposestoindividuals,communities,andtheauthorityandlegitimacyofthestate(seeBarker,2007;Dubber,2002;LoaderandWalker,2007; Miller,2013;RuthandReitz,2006).Whenpeopleexpressfearofcrime,itistypicallyviolentcrimethatisintheforefrontoftheirminds,nottheft,pick-pocketing, orresidentialburglary(ZimringandHawkins,1997).Failedstates,bydefinition, havelargelylosttheabilitytoensurethephysicalsafetyofcitizensinanysystematicandpredictablesense.

Inaddition,dramaticallyrisingandsustainedhighriskof lethal assaultisacrisis–muchaseconomicrecessions,outbreaksofcommunicablediseases,andterrorist attacks–andshouldpromptasearchforanunderstandingofitswiderimplications vis-a-visthestateanditscapacitytopreventandcopewithacrisis.Whilenonviolentcrimemaypreoccupypeopleandgeneratefrustration,resentment,and evenfear,itisfarlesslikelytoinducethekindofdeepanxietythatattachesto lossoflifeitself.Homicide,then,isaparticularlypotentsocialriskthatdeserves greaterexplorationforitspoliticalimplications.

Morepragmatically,homicidedataarelessplaguedbymeasurementerror thanothertypesofviolence,whichfallpreybothtochangesindefinitionsover timeaswellascross-nationalvariationinrecording.Arobustliteraturefinds thathomicideandviolentcrimeratesriseandfallinfairlyclosetandem,particularlywhenconsideredoverlongperiodsoftime(Eisner,2008;Fajnzylber etal.,2000).Thus,Irelyonhomicidebothasaserioussocialprobleminits ownrite,aswellasaproxyforunderstandingratesofseriousviolencemore generally.

Homicide,fourways

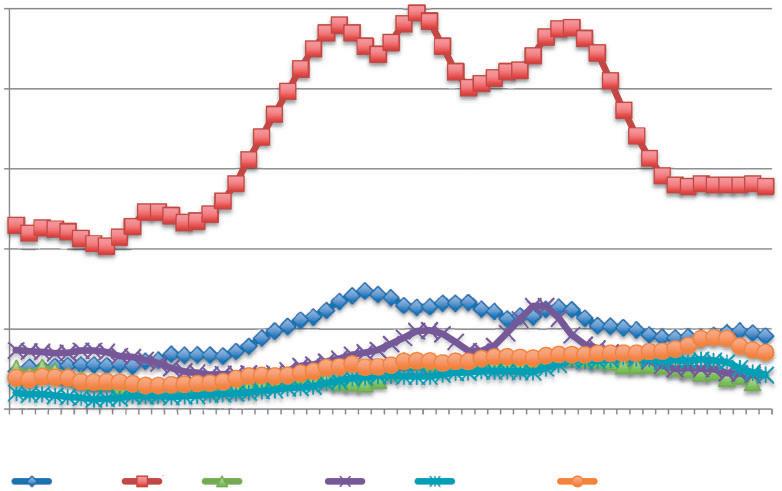

HereIillustratethemagnitudeofhomicideintheUSinfourdifferentwaysin ordertounderstanditsexceptionalism–thestandardrateper100,000,riskduring anormallifespan,peakratesbystate,andratesbyraceandgender.4 Figure1 illustratestheincreasesinhomicideratesacrosssixcountriesinthepost-warperiod (US,Canada,EnglandandWales,Denmark,Netherlands,Italy).Thesesixcountriesreflectthetypesofpoliticaleconomiesthatthepunishmentliteraturehas identifiedwithvaryingratesofimprisonment(seeCavadinoandDignan,2006; Lacey,2008):liberalmarketeconomies(US,Canada,andEngland/Wales);conservativecorporatist(NetherlandsandItaly);socialdemocracies(Denmark).Iuse three-yearmovingaveragesforvisualclarity.

Twoobservationsarenoteworthy.First,theUSisanextremeoutlierforthe full60-yearperiod.The lowestrate ofhomicide–4.0per100,000in1957–is 33percenthigherthanthehighest peak rateacrosstheothernations–Canada, 3.0in1975.Second,thethree-yearmovingaveragepeakUSrate(9.9in1980)is morethanthreetimesthepeakrateofCanadaandmorethanseventimesthepeak ratesinDenmarkandtheNetherlands(1.3,three-yearmovingaverageinboth countries).

Whilehomicideratesper100,000canillustratethedramaticdifferencesbetween theUSandotherdemocracies,thesefiguresaredifficulttocomprehend.Amore comprehensibleapproachisaheuristicthatcapturesaroughestimateofhomicide riskoveranormallifespanifratesremainedthesameoverone’sfulllifetime.5 Table1illustratesthe1960homiciderateforthesixcountries,aswellastherough calculationofriskoveralifespanin1960,eachcountry’speakhomiciderateand riskatthatrate.InEnglandandWales,atitspeakin2003,theliferiskofhomicide wasonein672,adramaticincreasefromthelifetimeriskofroughlyonein2164in 1960.Bycontrast,intheNetherlands,thoughtheliferiskofmurderreachedits peakin1996andhadincreasedsubstantiallyfrompreviousdecades,itpeaksata veryremoteonein975.

Onceagain,theUSisanextremeoutlier.Evenatitsrelativelylow1960rate (onein261),liferiskofhomicideintheUnitedStateswasgreaterthananyother country’s peak (Canada,in1975,atonein440).Ifhomiciderateshadremainedas highastheywerein1980,individualsbornthatyearfacedroughlyaonein131risk ofhomicide,nearlythree-and-a-halftimesashighasthepeakriskinCanada,five timesashighasEnglandandWales,andatleastseventimesthatofthepeakriskin theNetherlandsandDenmark,andonlyslightlylowerthantheriskofdyingina caraccidentintheUnitedStates.6 Whiledifferencesacrossraceandclassmake theseriskshigherforsomegroupsandlowerforothers,thepervasivenessof murderduringthehighcrimeyearsmadeitasocialconditionthatwouldhave beendifficultnottonotice,particularlysinceotherviolentcrimewasalsohigh.

Suchriskcalculationsforthelowviolencecountriesfurtherdrawthesedifferencesintosharprelief.InDenmarkandtheNetherlands,evenifthemost Table1. Riskofhomicideover75-yearlifespan7

homicidalyearscontinuedforalifetime,onlyoneincloseto1000personswould bemurdered.Attheirlowestpoints,thisriskdropstoavirtuallyunknownone in3400and4400,respectively,puttingtheoddsofbeingavictimofhomicidein thesecountriessomewherebetweenchokingtodeathanddyinginabicycle accident.7

AthirdwayofunderstandingtherealitiesoflethalviolenceintheUSinthe post-warperiodistoconsiderpeakrates.Figure2showsthehomicideratesfor eachstatebetween1960and2010,asastackedareachart.Theactualratesarenot importanthere.Rather,wewanttoobservetheoveralltrend.Muchismadeof 1980astheapexofthehomiciderateintheUnitedStates,afterwhichimprisonmentshouldhavelevelledoff(e.g.Western,2006).Indeed,between1950and1980, thehomicideratemorethandoubled,increasing122percentfrom4.6to10.2 murdersper100,000.

Buthomicideratesremainedveryhighevenafter1980,dippingbarelyperceptiblybeforerisingagainin1990s.Thenationalhomicideratedropped24percent between1980and1995(from10.2to8.2),asmalldecreaseincontrasttothe155 percentincreasebetweenthelowestrateof4.0in1957,andthe1980peak(10.2).In somestates,andforsomegroups,thepeakratedidnotoccuruntilthemid-1990s. MurderratesinWisconsindonotreachtheirpeakuntil1991,andstatesasregionallydiverseasAlaska,Connecticut,Louisiana,NewYork,OklahomaandSouth

Dakotadonotreachpeakhomicideratesuntilthemidtolate1990s.Moreover, fewstatessawappreciabledeclinesduringthisperiod.

Notuntiltheturnofthecenturydoratesbegintocomedowntopreviouslevels andonlytowardtheendofthefirstdecadeofthe21stcenturydomurderrates reachorfallbelowthoseofthepreviouspost-WorldWarIIlows.8

Finally,homicideriskisunevenlydistributedthroughoutthepopulationand examiningratesinthisfashionalsorevealstheextenttowhichhomiciderates remainedhighformanygroupswellintothe1990s.Table2illustratesmurder riskoveranaveragelifespanbyrace(African-American/white)andgenderfor 1960,1994,and2004.9 Whitefemaleshavelongenjoyed security frommurderat dramaticallyhigherratesthananyothergroup.Infact,attheirlowestrisk,before andafterthecrimewave,whitewomenexperiencedlifetimeriskofhomicide atratescomparabletoaverageoverallratesintheNetherlandsandEngland andWales.10 Amongwhitemales,however,lifetimerisksattheirebbin1960 arestillhigherthanthehighestoverallhomiciderisksinotherdemocracies(see Table1).

Bycontrast,andremarkably,blackfemalelifetimehomicideriskisconsistently higher thanwhitemalerates.Thisisparticularlystriking,giventheoverallgender biasinviolentvictimization(maleonmale),andalmostentirelyoverlookedby crimeandpunishmentstudies(BrookmanandRobinson,2012).Thefocuson racialdisparitiesinimprisonmenthasobscuredtheriskofdeadlyvictimization forblacksgenerally,buthasparticularlyrenderedinvisiblethelethalviolenceto whichAfrican-Americanwomenareroutinelyexposed(seeLane,1989;Roth, 2009).

Moststrikingly,African-Americanmalelifetimeriskofhomicidedwarfs othergroupsatanincredibleonein20in1994.Between1990and1995,black malesweremurderedatarateseventimesthatofwhitemales.Infact,in1995,in absolutenumbers, moreAfrican-Americanmenweremurderedthanwhitemen, astaggeringfact,giventhatblacksconstituteroughly12percentoftheUS population.12

Inadditiontoraceandgender,riskofhomicideforyoungpeoplealsocontinued torisethroughoutthe1990s.Table3provideshomicideratesforyoungpeopleby race/genderandrevealsthatratesforbothblackandwhitemales,aswellasblack Table2. Riskofhomicideover75-yearlifespanbyraceandgender

females,didnotpeakuntilthemiddleofthatdecade.Ratesforwhiteteenagemales rosefrom5.4in1980to8.9in1994andforblackfemaleteens,from6.8to10.2in thesametimeperiod.Similarly,whiteyoungmen18–24weremoreexposedto homicidein1994than1980,aswereblackfemales.13

Onceagain,youngblackmalesexperienceddrasticallyhigherriskofhomicide, atarateof26.1in1980for14–17-year-oldsand98.5for18–24-year-olds,which rosetoratesof72.9and188.3,respectively,in1994.Moreover,in1994,black malesbetween18and24yearswerenearlyanorderofmagnitudemorelikelytobe murderedthanwhitesofthesameagewhenblackmalerateswere188,butonly19 forcomparablewhitemales.Itisworthnotingthat,by2004,blackmaleratesof homicideforteens14–17hadfallenonlytotheir1980levels,incontrasttoother groupswhoseratesfellfarmore.Onceagain,whitefemalesarefarmoreinsulated fromhomicide,withyoungwomen18–24havingapeakrateof5.5per100,000in 1980,whichhadfallento3.1by2003.Whileyouthdeathsfromhomicidehave declineddramaticallyacrossallracialgroups,blackyouthratesdeclinedtheleast (WhiteandLauritsen,2012).

Finally,butnotably,thoughoverallriskisclearlyhighestforAfricanAmericans,thegreatest increase inhomicideratesbetween1960and1995was forwhitemales,growingmorethan150%from3.6per100,000to10.9.White femaleandblackmalelifetimeriskroughlydoubledaswell.Whilewhitefearof crimeduringthistimewasdemonstrablyrelatedtoracialbiases,weshouldnotrule outthepossibility–indeedlikelihood–thatitwasalsorelatedtoincreasesinreal risk.14

Insum,homicideintheUnitedStatesisexceptional,relativetootherdeveloped democracies.Inaddition,itrosedramaticallybetween1965and1980,remained highwellintothe1990sandrelativelyhighuntiltheturnofthecentury.Moreover, lifetimeriskofhomicidegrewforallgroups,regardlessofage,raceorgender, diffusingacrossthepopulationrapidly.Inotherwords,riskofseriousviolence spreadforvirtuallyallAmericansduringthistimeperiod.African-Americansand

youngpeople,however,sufferedparticularlyhighratesofvictimizationandyoung blackmaleswereandremainexposedtoanastonishinglyhighriskofmurder, relativetowhites.

Homicideinthecontextofsocialinequalityandpolitical institutions

HereIsituatehomicidewithinarangeofsocialinequalitiesandpoliticalsystems. Table4reproducesaversionofthepoliticaleconomymatrixofferedbyLacey (2008)forunderstandingcomparativepunishmentregimes.Lacey’sanalysisprovidesacrucialadditiontothepunishmentscholarshipbyhighlightingthepolitical economyofdifferentlystructureddemocraticsystemsandtheirrelationshipto ratesofpunishment.Heranalysissuggeststhatliberalmarketeconomies(LME), withtheir(typically)two-partysystemsandlesscoordinatedmarketsproduce feweroptionsbeyondmoreimprisonmentinresponsetocrimeconcernsthan coordinatedmarketeconomies(CME)andsocialdemocracies(SD),where multi-party,coordinated,andcorporatistsystemsinsulatelawmakerstoprovide greateropportunitiesforcoordinatedresponsesbeyondjustpunishment.

Iaddseveralothermeasuresofriskexposuretotheanalysistoillustratethe consistencyoftheUSinexposingthecitizenryasawhole–butespecially African-Americans–tohighersocialrisks:peakhomicideratessince1950, infantmortalityratesandtheOrganizationforEconomicCo-operationand Development’s(OECD)rankingofeachcountryintermsofrelativelevelsof socialinequalityinaccesstoeducation.15 Iincluderacialbreakdownsfor

Notes: aNon-Hispanicwhitesonly; bDataareonlyavailablefor2010/2011; cAggregateratesacrossracial groups.

EnglandandWaleswhereavailable,thoughreliabledataonracialandethnic categorizationofsocialindicatorsaremoredifficulttoobtainoutsidetheUnited States.Moreover,itisnotclearwhattheappropriatecomparisonsare.For EnglandandWales,Iusethedataforblack-Caribbeanandblack-African, thoughthesepopulationsarerelativelyrecentimmigrantstoEngland,rather thandescendantsofslaveryandapartheid.

RatherthansituatetheUSwithotherliberalmarketeconomiesasLacey (2008)andothersdo,IplacetheUSoutsidetheframeworktoindicateitsextreme status.Peakhomiciderates forwhitesintheUSaretwo,three,orfivetimestheir peakintheothercountries.ButpeakratesforAfrican-Americansaresixtimes higherthanforwhiteAmericansandseveralordersofmagnitudehigherthanthe averagepeakratesinthelowviolencecountries.Ratesofmurderaremuchhigher forblackBritonsthanforwhitesaswell,buttheoverallmurderrateisatleastsix timeshigherforwhiteAmericansthanforwhiteBritons(atthepeak)andcloser toninetimeshigherforblackAmeri cans,comparedwithblackBritons. Moreover,blacksintheUSweremurderedatratessixtoseventimesthatof whiteAmericanswhereastheblacktowhiteratioinEnglandandWalesisless thanfive.

InfantmortalityratesforwhitesintheUSareslightlyhigherthanforEngland andWales,comparabletoCanadaandtwiceashighasDenmark.Blackinfant mortalityrates,intheUS,however,aremorethantwicethewhiterateandmore than50percenthigherthanratesforCaribbeanandAfricanBritons.Withrespect toeducation,theOECDBetterLifeIndexranks36countriesaccordingtoseveral measuresofeducationalquality.TheUSisranked21stonstudentskillsand22nd onsocialinequalitiesineducation(higherscoresreflectmoreinequality).16 By contrast,theUKranks14thonstudentskillsand15thonsocialequalityofeducationalopportunity.Canadaisexceptionalinthisranking,andtheNetherlands andDenmarkalsoperformsubstantiallybetterthantheUSonbothmeasures.In fact,theUSscoresareclosertoChile(25/29)andGreece(30/27)thantoits NorthernneighborsorEuropeancousins.

Finally,imprisonmentratesfollowasimilarpattern,withblackimprisonment ratesdramaticallyhigherthantheothers,butwhiteratesalsothreetimeshigher thanoverallratesintheUKandsixtoeighttimeshigherthantheother countries.17

Itisimportantnottoglossoversubstantialdifferencesinsocialriskbetween whitesandtheworstoffracialminoritypopulationsinotherrichdemocracies. However,whileweshouldbecautiousindrawingconclusionssincethedataare sparse,wheredataareavailable,boththereallevelsofrisk,aswellasthemagnitudeofthedifferencewithwhites,issubstantiallyhigherforblackAmericansthan forminoritieselsewhere.18

Inshort,thepopulationoftheUSasawholeisexposed tohighersocialrisksinmostcategories,particularlyviolenceandinequality.But abovetheUS,generally,liesaseparaterealmofinequalityoccupiedbyalarge portionofAfrican-Americans.Thepurposehereisnottoisolatetherelative amountofvariationinimprisonmentexplainedbythesefeaturesbut,rather,to

highlighttheclusteringofhighriskintheUnitedStates,generally,andforAfricanAmericansspecifically,relativetootherdevelopeddemocracies.

Violenceandpunishmentasstatefailure

Thissectionoffersaframeworkforunderstandingtheclusteringofrisksinthe UnitedStatesanditsimplicationsforthesocio-politicaldynamicsofcrimeand punishment.Ifhighimprisonmentisundesirable,bothasanormativematter indemocraticsystemsandasaweakmechanismforreducingratesofcriminal offending,thenbothhighlevelsofseriousviolenceandhighratesofpunishment canbothbelimitedformsofstatefailure.Ihavereferredtothiselsewhereasthe securitygap(Miller,2013)and,seeninthisway,explanationsfortheexceptional ratesofpunishmentintheUSthatdonotaccountforexceptionalratesofmurder, poverty,incomeinequality,andotherinsecurities,overlookthelargerinstitutional contextinwhichbothcrimeandpunishmentoccur.HereIsituaterisingpunishmentandhighviolenceintheUnitedStateswithintheinstitutionallandscapeof USpoliticsthatalsoproducelowsocialwelfarespending,highratesofpoverty, andracializedinequality.

Fragmentationandracialization

AvastliteraturehaspuzzledoverthepeculiarnatureofUSpoliticsthatproduces substantialdifferencesinsocialmovementsandpolicyoutcomesintheUnited StatescomparedtoEurope,includinghigherratesofincomeinequality,poverty, poorerhealthoutcomesandlimitedsocialsafetynets.Withafewexceptions, scholarsofcrimeandpunishmenthavenotleveragedthiscomparativeframework forunderstandingvariation(butseeLaceyandSoskice,2013).Whilescholars disagreeontheprecisecausalmechanismsthatdrivethesedifferences,thereis somecommongroundsuggestingthatdispersalofpoliticalpower–forexample, separationofpowers,astrongupperlegislativechamberwithdisproportionate representation,arobustandactivejudiciary,andfederalism–isanimportant causalfactor.Scholarslinkthefragmented,decentralizednatureoftheUSpolitical systemto:weakpartydisciplineandobstaclestothecoordinationofpublicgoods (HackerandPierson,2010;Soskice,2010);impedimentstosocialmovementsand labororganizing(Lowi,1984;Sossetal.,2008);challengestotheimplementation ofsocialpolicy(Wildavsky,1984);limitationsonthepoliticalcapacityoflocal governance(Miller,2010;Peterson,1981);andthemaintenanceofracialhierarchy (Katznelson,2005;Riker,1964).

Separationofpowersandsingle-memberdistrict/winner-takes-allsystemsare alsobothlinkedtolowersocialwelfareprovisions(Moosbrugger,2012).Indeed, studiesofconstitutionalstructureswithmanyvetopoints–venueswheresmall groupswithstrongmaterialorideologicalinterestscanblockbroadmajorities–tendtohavelowersocialwelfarespending,weakersafetynets,andgreater

inequality(Huberetal.,1993;Lijphart,1999;ManzaandBrooks,2007).Crossnationally,thesefactorsarealsotiedtoratesofincarceration(Downesand Hansen,2006).

OnemightreasonablyaskhowthesefeaturesoftheUSconstitutionalframework–whichlongpre-datemassincarceration–contributetocontemporarypoliticaloutcomesonpunishment.Whilethesebasicfeatureshavelongimposed generalobstaclestotheproductionofcollectivegoods,thestructureunderwent substantialchangesinthe20thcentury,inlargepartasaresultofexogenous forces,suchasworldwars,theGreatDepression,andstrongsocialmovements, whichproducedtwoimportantchangesforourdiscussionhere.

First,economiccrisescontributedtoagrowingnationalizationofissuesand helpedpushthroughrobustsocialwelfarereforms(e.g.theNewDeal,Social Security,andtheGIbill),whilealsoreifyingandentrenchingtheopportunities forvetoingtheirdistributionbyraceandclass.19 Forexample,whiletheSocial SecurityActandGIBillwereaimedatamelioratinginequalityand/orpromoting prosperity,theirbenefitswereleastlikelytoflowtoAfrican-Americans(Dudziak, 2000;Katznelson,2005).Akeymechanismforthisunevendistributionwasthe federalsystem,whichfacilitatedthecapacityofstatestoblocksocialwelfareprovisionsortolimittheirdistributiontoblacksentirely(Riker,1964).Similarly,while theCivilRightsActof1964andtheVotingRightsActof1965werealsomajor piecesofnational,sociallegislation,theirenforcementwashighlyunevenacross thefederallandscapeandinsomestates,resistancetosuchrightscontinuestoday (Behrensetal.,2003;ParkerandBarreto,2013).

Thisunderlyingpoliticalopportunitystructurehaslongbeenexploitedby opponentsofbroadsocialgoodsintheUnitedStatessuchthat,evenasthe nationalgovernmenttookonawiderangeofnewissuesinthesecondhalfof the20thcentury,includingtheenvironment,civilrights,healthcareandother formsofsocialpolicy,thefragmentedpolicylandscapethwartedthemoresweepingeffortsatreformand,wherelegislationwassuccessful,facilitateditshighly unevenimplementationacrossregion,raceandclass(Sossetal.,2008).

Acontemporaryexampleisthestate-levelresistancetotheexpansionof Medicaid–thesocialinsuranceprogramforthepoor.FacilitatedbyaSupreme Courtdecisionthatoverturnedtheportionofthe2010PatientProtectionand AffordableCareActthatrequiredstatestoexpandtheireligibilityforMedicaid, somestatesaredecliningtoexpandthiscoverage.20 Manyofthesestatesarehome tosomeofthenation’spoorestresidents,andalsoincludevirtuallyallofthe southernstatesthathavealonghistoryofexploitingthefragmentationandjurisdictionalfluidityoftheUSsystemtoopenlydefyfederaleffortstodismantlesegregationandreduceinequality.21 Thelikelyresultisthatraceandclass-based disparitiesinaccesstohealthcarewillpersistandperhapsevenincrease.

Second,dramaticeconomicchanges,whiteracialhostilityandsocialunrest,and risingviolenceinthe1960sand1970scollidedwiththisdeeplyfracturedUSpolitical landscape,evenascivilrightswereprovidinggrowingopportunityformiddle-class blacks(Murakawa,2014;Weaver,2007).Thefragmentednatureofpolicymakingin

theUSthathaslongmadesocialwelfarepolicychallengingwasespeciallydifficultto overcomeinthecontextofextremeratesofseriousviolence,collapseofcities,and deephostilitytowardblackprogressbysegmentsofthewhitepopulationinthe1970s and1980s.

Relatedly,politicalcapacityisunevenacrosstheUSfederalsystem,withcities andmunicipalitiesnotoriouslyintheweakestpositiontoenactredistributivepolicy (Peterson,1981).AsLaceyandSoskice(2013)argue,USfederalismcreatesincentivesformedianvotersatthelocalleveltoavoidspendingmoneytoaddress criminogenicconditions,suchaseducationandemployment,eveniftheywould otherwisewishtodoso,becausesuchmeasureswouldlikelyimposehigherpropertytaxesonhomeowners.Instead,localsupportformoreandlongercriminal sanctionscandeflectcostsontoalargerandmoredispersedpopulationatthestate level.Thissituationbecameespeciallypathologicalinthesecondhalfofthe20th centuryasdisadvantageineconomicandeducationalopportunitybecamemore raciallyconcentratedatthelocallevel.

Paradoxically,thoughperhapsnotcoincidentally(seeWeaver,2007),fromthe early1950sandwellintothe1970s,justasviolencewasrisingandopponentsof socialwelfarepolicyandracialprogresswereusingvetopointsofUSpoliticsto blocknewlegislation,statelegislaturesandlocallawenforcement,jails,andprisonswerebecomingmoreprofessionalized(FeeleyandRubin,2000;King,2000; Squire,2007).Aspoliticaldemandtoaddresscrimeincreased,opportunitiesfor respondingwereeasilyfunneledintotheoneareathatcouldrespondmostvisibly andimmediatelytothecrisisofcrime,disorder,andconcentratedpoverty:police, statecriminallaws,andprisons.22

Takentogether,fragmentationandracializationhelpexplainthevariationin socialinequalitybetweentheUSandotherdemocraciesinseveralways.Nomatter one’spreferredtheoryofthecausesofseriousviolence–incomeinequality,low levelsoftrustandlegitimacy,spatiallyconcentratedpovertyandinequality,gun availability–thefragmentedUSsystemhasbothcontributedtothemandmade themdifficulttorectify(seeHackerandPierson,2010onincomeinequality; LaFree,2002andRoth,2009ontrust/legitimacy;Goss,2008onguns;Massey andDenton,1993,PetersonandKrivo,2010onspatialsegregation).Thus,as violenceincreasedinthelatterhalfofthe20thcentury,evenwherevoterswere sympathetictomoreinclusionarypolicyproposalsratherthanpurelypunitive ones,theylikelysupportedpoliciesthatfurtherentrenchedraceandclassdivisions andratcheteduppunishment(knowinglyorunknowingly).

Moreover,andcrucially,theseinstitutionalarrangementsofUSpoliticsconstrainpublictrustintheabilityofthestatetoameliorateseriousviolencethrough means otherthan punishment.Supportfor,orsimplytoleranceof,increasingpunishmentmaythusreflectconcernamongtheUSpublicthatmorestructuralsolutionsareunavailableand/orunlikelytobeforthcoming.Inotherwords, thepolicy alternativesthatemergewhenviolenceishighorrisingaresubjecttothesame racializedinstitutionaldynamicsthathavealsocontributedtoandmediatedearlier effortstoreduceinequality,racialdisparitiesandpovertygenerallyintheUnited

States.ThesesamefeaturesthencontinuetopushAfrican-Americans,specifically, andthepoorgenerally,intothemostmarginalizedcornersoftheUSpolity(jails andprisons)whenviolenceandinsecurityrise.23

Whileitisimpossibletoknowthecounter-factual–aUSstatewithoutthemany andvariedopportunitiesforsystematicallyblockingorunevenlydistributingbroad socialwelfareprovisions–thisaccountsuggeststhattheveto-ladenandfragmented natureofUSpoliticalinstitutionshasfacilitatedsuchactivity,particularlywhengovernmentpoliciesmightassistblacks.Thepunitiveapparatusofthejusticesystemmay bealastresortmechanismforconfrontinghighlevelsofviolenceandsocio-economic exclusion,aboveandbeyondthelong-standinguseofsuchinstitutionsforthemaintenanceofracialhierarchy.Inthissense,highriskofmurder,economicmarginalization,andimprisonmentarefeaturestheUSstate’songoingfailuretosecurethe citizenry–particularlyblacks–moreequitably(seealsoWacquant,2007).

Thegrowthoflegalismin(crimeand)justice

Finally,relatedtothesefeaturesofUSexceptionalism–andinpartasafunctionof them–isadeeplyrootedlegalism,acoredimensionofUSpoliticsthatroutinely movespoliticaldisputesintothelegalarenaandframespoliticalproblemsinlegal terms(Kagan,2001;Scheingold,1984;Silverstein,2009;seealsoRobertson,2009). Thisisproblematicfromtheperspectiveofsocialchangeandtheproductionof socialgoods:‘‘Adversariallegalisminspireslegaldefensivenessandcontentiousness,whichoftenimpedesociallyconstructivecooperation,governmentactionand economicdevelopment [itis]inefficient,costly,punitiveandunpredictable’’ (Kagan,2001,4;seealsoScheingold,1984).

Despitethewell-knownlimitationsontheuseoflegalclaimsastoolsforbroad socialpolicychange,resistancetothecarceralstateamongpoliticalelitesisheavily focusedonproceduraljustice.Suchafocusisdeeplyintertwinedwithcivilrights claimsaboutunfairtreatmentbyagentsofthecriminaljusticesystemandunjust crimepoliciesenactedbylawmakers.Ironically,itwasthepersistentthreatofwhite terroristviolenceagainstblacksandthe lack ofstateresponse,inthefirstdecadeof the20thcentury,thatformedthebackdropfortheformationofthenation’smost prominentcivilrightsorganization(NationalAssociationfortheAdvancementof ColoredPeople(NAACP)),andsuchsecurityfromsuchviolencewasacorecomponentoftheearlycivilrightsstruggle.Moreover,earlycivilrightsactivistsappear tohavearrivedreluctantlyatlegalstrategies,afterseeingpoliticalmovements repeatedlythwarted,oftenthroughviolentmeans(seeFrancis,2014;Murakawa, 2014).

Inthe1960s,whenviolenceandarrestratesexploded,litigationoverpoliceand prisonsfurthersolidifiedthelegalstrategy,drawingattentiontothehorrificconditionsinprisonsandpolicebrutality(Gottschalk,2006).Insomerespects,this wasanaturaloutgrowthofthesuccessfullegalchallengestosegregationthat emergedinthefirstdecadeaftertheSecondWorldWar.Someresearchindicates acleareffectoflitigationonchangestotheseinstitutions(seeFeeleyandRubin,

2000;Francis,2014,foramorehistoricalaccount).Others,however,suggestthat suchstrategiesmayhavealsocontributedtothegrowthofprisonconstructionby reconfiguringprisonlitigationoutcomesawayfromde-carcerationandtowardthe needfornewer,morehumaneprisons(Gottschalk,2006;Schoenfeld,2010).Inany case,consistentwiththewell-knownproblemsofadversariallegalism,aconsequenceoflitigationwasthatthelargermovementmessage–thatdeepeconomic disparitiescontributetocriminaloffending–wasobscuredinthelitigationprocess (Schoenfeld,2010;seealsoScheingold,1984foramoregeneraldiscussion).24

Bythe1980sand1990s,astheracialconsequencesoftoughlawandorder policiesbecameclear,astrongsetoflegalinstitutionswerewellsituatedto attackstateactiononpunishment,specificallythelargestcivilrightsandliberties organizationsinthecountry–theAmericanCivilLibertiesUnionandtheLegal DefenseFundoftheNAACP.Thelegalframeworkofthesegroups,however,has leftchallengestostate inaction withrespecttoreductionsindisproportionaterisk ofviolenceandcriminogenicconditions–thesecuritygap–largelyoutofthe discussion.TheNAACP,forexample,hasfourprojectslistedunderJustice Advocacyonitswebsite:SentencingReform;EffectiveLawEnforcement; EliminatingBarrierstotheFormerlyIncarcerated;andSurvivorsofCrime.Only recently,however,hasthelattertopicbecomeapartoftheagenda.Between2004 and2010,theNAACPAnnualReportmentionedracialdisproportionalityin arrestandincarcerationbutmadefewreferencestothedifferentialexposureof blackstolethalviolence.Infact,thereferencestocrimeareprimailyinrelationto theproliferationofhandguns,policeviolence,andhatecrimes.Ironically,giventhe organization’soriginsintryingtoreducebrutalwhiteviolenceagainstblacks,the 2009AnnualReport,celebratingtheNAACP’s100thanniversary,makesnomentionofthedisproportionateriskoflethalviolenceforAfrican-Americans.

Decadesoflitigationandlegalargumentsurgingjudgestodisruptthesteady marchofincreasingpunishment,however,havedonelittletoreducearrestand imprisonment,norhavetheycontrolledseriousviolenceorotherrisks.Whilethe roleofthefederalcourtsinunderminingtheovertracistpracticesofstateandlocal criminaljusticesystemsinthe1970siswelldocumented(FeeleyandRubin,2000), thefederalcourtshavehadmoredifficultydealingwithmoreinstitutionalized formsofracialbiasandwithlengthycriminalsentencingschemesthathavedisproportionatelyaffectedminorities(MurakawaandBeckett,2010).25

Thislimitationisapparentincasessuchas McKleskyv.Kemp, 26 inwhichthe courtisaskedtomakeuseofaggregateevidencethatthestateofGeorgiaimplementeditsdeathpenaltyinahighlyraciallydiscriminatorymanner.Unableto provideevidencethatthestatediscriminatedagainst McKlesky perse,thecourt rejectedhisclaim.Similarly,incasessuchas U.S.v.Johnson27 and U.S.v. Armstrong, 28 inwhichdefendantssoughttodemonstratediscriminatorytreatment incocaineprosecutions,federalcourtshavenotimposedstrictscrutinystandards forassessingtheseclaimsandhaveside-steppedthelargerissuesofraciallydisparatecriminaljusticeoutcomes(seealsoMurakawaandBeckett,2010;Provine,2007 forarelateddiscussion).Moreover,inracialprofilingclaims,whenlaw

enforcementagencieshavebeenabletoprovidenon-racialreasonsforstopping citizens,federalcourtshaveusuallyupheldthepolicepracticeanddeclinedto inquireintothethinkingbehindofficers’actions(HeumannandCassak,2003).

Beyondracialbias,federalcourtshavealsobeenlargelydeferentialtolegislaturesoncriminalpunishmentsmoregenerallyandtheincreasesinmandatory minimumsentencesandotherlengthysanctionshavewidenedracialdisparityin thejusticesystem(Schlesinger,2011).29

Inotherwords,aslitigationstrategieshavebeenpursuedasameansbywhichto limit statecapacity–intheformofreducingitsuseofrepressivepracticesinsuch disparateandexcessfashion–whathaslargelybeenobscuredisthe failure ofthe statetoincreasethesecurityofthemostmarginalizedfromawiderangeofsocial risks,includinglethalviolence.

Conclusion:Theorizingviolenceandpunishmentasformsof statefailure

TakingacloserlookatthenatureandextentofseriousviolenceintheUnitedStates revealsaclusterofsocialrisksthatdrawintosharpreliefitsexceptionalstatusinfar morethanjustimprisonment.Further,usingthelensofsocialriskhighlightsthe relationshipbetweenunder-securityandover-punishmentandtheroleofthestatein producingboth.MassvictimizationisafactoflifeintheUnitedStatesbut,like othersocialrisks(incomeinequality,povertyandsoon),itisespeciallyconcentrated amongAfrican-Americans.Ifmassimprisonmentisthetragedyof21st-centuryUS, masssocialrisktoblacksisthetragedyofUSpolitics.

Reconsideringsecurityfromviolenceasacollectivegood,acorestateresponsibilityandasonemeasureofstatesuccesscanprovideadditionalinsightintothe mechanismsthroughwhichviolencecanbekeptlowacrosspopulations,thelink betweenviolenceandotherformsofsocial,racialandeconomicinequalitiesandthe abilityofpoliticalsystemstorepresentpopulationsatmostrisk.Greatertheorizing aboutthelinkbetweenlevelsofviolenceandtheuseofstaterepressioncanhelpus betterunderstandtheconditionsunderwhichstatesaremostcapableofandlikelyto promoteawiderangeofpublicgoods.Reducingimprisonmentmaybemoretiedto sustainedreductionsinseriousviolenceandotherformsofsocialinequitiesthanwe haveheretoforeassumed.ThepeculiarcollectionofUSpoliticalinstitutionsthat haveproducedsuchhighratesofviolence,punishment,andinequality,however, makesuchreductionslesslikelyintheUSthaninotherdemocraticsystems.

Notes

1.Thereisarobustliteratureinsociologythatexploresthecausesofhomicidebut theseworksrarelyanalyzetheimpactofratesoflethalviolenceonpoliticaldynamicsofcrimeandpunishmentorthepotentialrelationshipbetweenthepoliticalcauses ofhighratesofmurderandthoseofimprisonment(e.g.BursikandGrasmick,1993; PetersonandKrivo,2010;Sampson,2012).

2.Oncrime,seeDubber(2002);LoaderandWalker(2007);Zedner(2009).

3.DistinctfromGarland,Ifocusonlyonviolentcrimeforreasonsdiscussedinthis section.

4.Themostcomprehensive,overtimesourceofhomicideratescross-nationallyisthe WorldHealthOrganization’smortalitydata.Whilethedataarenotcompletefor eachcountry,theyprovidelongertrendsthananycountryspecificreports. Iextracteddatafromthecategory‘‘homicideandinjurypurposefullyinflicted–notwar’’fromtheICD-7,ICD-8,ICD-9,andICD-10.Availableat:http:// www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/mortality/en/index.html.

5.LifetimehomicideriskiscalculatedfollowingRoth(2009:498,fn5)(100,000/(rate per100,00*lifeexpectancy)).DistinctfromRoth,however,Iuseastandard 75yearlifespanforcomparabilityacrosscountriesandtominimizetheoverestimationofriskduetogrowinglifeexpectancy,whichaddselderlyyears,atimeof lifewithexceedinglylowriskofmurder.IamgratefultoRandyRothandKevin ReitzforsuggestingthatIconveyhomicideratesinthisfashion,andtoAnnePiehl andLaurieKrivofortheiradditionalsuggestionsforpresentingthedata.

6.NationalSafetyCouncil,InjuryFacts(2014:43).Itasca,IL:NationalSafety Council.

7.Homicideratesareroundedtothenearesttenthbutliferiskcalculationsaremade ontheunroundedhomiciderate.

8.NationalSafetyCouncil,InjuryFacts(2014:43).Itasca,IL:NationalSafety Council.

9.Violentcrimeratesshowasimilarpatternofgrowthandbegintodeclineinthe mid-1990sbuthavenotreachedthelowratesofthe1960s(averagerateacross thestateswas365per100,000,comparabletotheratein1976(362))(Bureauof JusticeStatisticsaspreparedbytheFederalBureauofInvestigation,Uniform CrimeReports,NationalArchiveofCriminalJusticeData).

10.USNationalCenterforHealthStatistics,Deaths:FinalDatafor2007,Vol.58,No. 19,May2010,andearlierreports.

11.Ofcourse,lifetimeriskforwomeninthosecountriesislikelytobeevenlowerthan theoverallnationalrisk.

12.Atotalof7913comparedto6939.FBI,UniformCrimeReport1995,‘‘Crimeinthe UnitedStates’’,p.14.

13.Spaceconsiderationslimitmorerefinedanalysisthatwouldincludesocio-economic class,butthereisevidencethatpoorerpeoplealsoexperiencehomicidesatamuch higherratethantheaffluent(LauritsenandHeimer,2010;Nivette,2011).

14.Thisarticleisnotaimedatunderstandinghowpeoplebecomecognizantofriskbut, elsewhere,Ihavenotedaclosecorrelationbetweenthehomiciderateandnewspapercoverageofcrimebetween1960and2000(Miller,2013).Iaddresstherelationshipbetweenhomicideandthepublicandpoliticalsalienceofcrimeinmy currentbookproject, TheMythofMobRule:ViolentCrimeandDemocratic Politics (undercontractwithOxfordUniversityPress).Itispossiblethatatpeak homicideratesintheUS,murderissopervasivethatmanypeople–notjustthe

worstoff–havepersonallyheardof,orevenknown,someonewhowasmurdered. Thisisasubjectforfurtherinquiry.

15.Sources:murderratesforUK:mosthomicidereportsdonotincludedatabyethnicitybuta2010/2011reportdidbreakdownhomicidevictimsby‘‘ethnicappearance’’ofthevictim(white,black,Asian,other,notknown)–Smithetal.(2012: 227,Table1c).MurderratesforUS:BureauofJusticeStatistics,Infantmortality rates,EnglandandWales(OfficeofNationalStatistics,InfantMortalitybyethnic group,2005);USCenterforDiseaseControlinteractivetables(http:// 205.207.175.93/HDI/TableViewer/tableView.aspx);Canada,Netherlands,and Denmark,WorldHealthOrganization(http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node. main.526)andCenterforDiseaseControl(http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ databriefs/db23.pdf);educationalinequality,OrganizationforEconomicCooperationandDevelopmentBetterLifeIndex(http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex. org/topics/education/);Homiciderates(WHO);Imprisonmentrates(exceptUS) (Walmsley,2000);USimprisonment(WestandSabol,2010:28)

16.Schoolinequalityisthedifferencebetweenaveragetestscoresofthehighestperformingschoolsinrelationtothoseoflowestperformingschools.

17.ImprisonmentratesforblacksinEnglandandWalesarealsomuchhigherthan thoseforwhites(EqualityandHumanRightsCommission(2011)‘‘Howfairis Britain?Equality,humanrightsandgoodrelationsin2010–thefirsttriennial review’’).However rates ofimprisonmentinEnglandandWalesaredramatically lowerthanthoseintheUSacrossallracialgroups.

18.SeeAlbrecht(1997),Granathetal.(2011),Junger-Tas(1997),PhillipsandBowling (2012)fordiscussionofminorityriskofviolenceintheNetherlands.

19.E.g.theSocialSecurityAct,PL74–271(1935),theNationalLaborRelationsAct, PL74–198(1935),theGIBill,PL78–346(1944).

20.PatientProtectionandAffordableCareAct,PL111–148(2010), National FederationofIndependentBusinessesv.Sebelius,132S.Ct.2566(2012).

21.SeetheHenryJ.KaiserFamilyFoundationanalysisofstateMedicaidExpansion: http://kff.org/health-reform/slide/current-status-of-the-medicaid-expansion-decision.VirginiaiscurrentlydebatingwhethertoexpandMedicaidandArkansashas approvedwaiversforMedicaidexpansion.

22.Thisaccountisnotcontradictorytothosethatusethelensofcivilrightsandthe maintenanceofwhitesupremacytounderstandincreasinguseofstaterepressive tools(Murakawa,2014;Weaver,2007).Onthecontrary,Ithinkbothinstitutional andracialframeworkscomplementandcross-fertilizeoneanother.

23.Thereis,ofcourse,statevariationintheseconditionsandpolicyresponses(see Lynch,2009forananalysisofArizona;alsoCampbell,2011onTexas).

24.ThecausesofviolentcrimearethesubjectofconsiderabledebateandImakeno claimsherethatimprovingeconomicconditionswillreduceviolence(see,forexample,LevittandDubner,2005;PetersonandKrivo,2010;Roth,2009).Isimply highlighthowtheemphasisonproceduralrightscanobscurelargerpolitical, socialandeconomicneedsanddemands.

25.See Powellv.Alabama (1932),287US45; Norrisv.Alabama (1935)294US587; Brownv.Mississippi (1936)297US278;and Mirandav.Arizona (1966)384US436.

26.481US279(1987).

27.309USApp.DC180(1994).

28.517US456.1995.

29.See Harmelinv.Michigan (501US957(1991)),severeandlengthysentencesdonot violatetheEightAmendment; Solemnv.Helm (463US277(1983))onproportionalityinEightAmendmentchallenges; Ewingv.California (538US11(2003)),on theconstitutionalityofCalifornia’sThreeStrikesYou’reOut.

References

AlbrechtH(1997)Ethnicminorities,crimeandcriminaljusticeinGermany. Crimeand Justice:Ethnicity,CrimeandImmigration:ComparativeandCross-National Perspectives 21:31–99.

AndersonE(1999) CodeoftheStreet:Decency,ViolenceandtheMoralLifeoftheInner City.NewYork:Norton.

BarkerV(2007)Thepoliticsofpain:Apoliticalinstitutionalistanalysisofcrimevictims’moralprotests. LawandSocietyReview 41(3):619–663.

BarkerV(2009) ThePoliticsofImprisonment:HowtheDemocraticProcessShapesthe WayAmericanPunishesOffenders.NewYork:OxfordUniversityPress.

BaumgartnerFRandJonesBD(1993) AgendasandInstabilityinAmericanPolitics Chicago,IL:UniversityofChicagoPress.

BehrensA,UggenCandManzaJ(2003)Ballotmanipulationandthe‘‘menaceof negrodomination’’:RacialthreatandfelondisenfranchisementintheUnitedStates, 1850–2002. AmericanJournalofSociology 109(3):559–605.

BermeoNandPontussonJ(2012) CopingwiththeCrisis:GovernmentReactionstothe GreatRecession.NewYork:RussellSageFoundation.

BrookmanFandRobinsonA(2012)Violentcrime.In:MaguireM,MorganRMand ReinerR(eds) TheOxfordHandbookofCriminology.Oxford:OxfordUniversity Press.

BursikJrRJandGrasmickHG(1993) NeighborhoodsandCrime.NewYork: LexingtonBooks.

CampbellM(2011)Politics,prisons,andlawenforcement:Anexaminationofthe emergenceof‘‘lawandorder’’politicsinTexas. LawandSocietyReview 45(3): 631–665.

CampbellMandSchoenfeldH(2013)ThetransformationofAmerica’spenalorder:A historicalpoliticalsociologyofpunishment. AmericanJournalofSociology 118(5): 1375–1423.

CavadinoMandDignanJ(2006)Penalpolicyandpoliticaleconomy. Criminologyand CriminalJustice 6(4):435–456.

ClearT(2007) ImprisoningCommunities:HowMassIncarcerationMakes DisadvantagedCommunitiesWorse.NewYork:OxfordUniversityPress.

DownesDandHansenK(2006) WelfareandPunishment:TheRelationshipbetween WelfareSpendingandImprisonment.London:CrimeandSocietyFoundation.

DubberMD(2002) VictimsintheWaronCrime:TheUseandAbuseofVictims’Rights. NewYork:NewYorkUniversityPress.

DudziakM(2000) ColdWarCivilRights:RaceandtheImageofAmericanDemocracy Princeton,NJ:PrincetonUniversityPress.

EisnerM(2008)Modernitystrikesback?Ahistoricalperspectiveonthelatestincrease ininterpersonalviolence(1960–1990). InternationalJournalofConflictandViolence 2(2):288–316.

FajnzylberP,LedermanDandLoayzaN(2000)Crimeandvictimization:Aneconomic perspective. Economia 1:219–302.

FeeleyMandRubinEL(2000) JudicialPolicymakingandtheModernState:Howthe CourtsReformedAmerica’sPrisons.NewYork:CambridgeUniversityPress.

FormanJ(2012)Racialcritiquesofmassincarceration:BeyondtheNewJimCrow. YaleLawSchoolLegalScholarshipRepositoryAvailableat:http://digitalcommons. law.yale.edu/fss_papers/3599/

FortnerM(2013)Thecarceralstateandthecrucibleofblackpolitics:Anurbanhistory oftheRockefellerdruglaws. StudiesinAmericanPoliticalDevelopment 27:14–35.

FrancisM(2014) CivilRightsandtheMakingofModernAmerica.Cambridge,MA: CambridgeUniversityPress.

GarlandD(1996)Thelimitsofthesovereignstate:Strategiesofcrimecontrolincontemporarysociety. BritishJournalofCriminology 36(4):445–471.

GarlandD(2001) TheCultureofControl:CrimeandSocialOrderinContemporary Chicago,IL:UniversityofChicagoPress.

GlazeLEandHerbermanEJ(2013) CorrectionalPopulationsintheUnitedStates,2012 NCJ243936.Washington,DC:USDepartmentofJustice,OfficeofJustice Programs,BureauofJusticeStatistics.

GoffmanA(2014) OntheRun:FugitiveLifeintheInnerCity.Chicago,IL:University ofChicagoPress.

GossK(2008) Disarmed:TheMissingMovementforGunControlinAmerica. Princeton,NJ:PrincetonUniversityPress.

GottschalkM(2006) ThePrisonandtheGallows:ThePoliticsofMassIncarcerationin America.NewYork:CambridgeUniversityPress.

GranathS,HagstedtJ,KivivuoriJ,etal.(2011) HomicideinFinland,theNetherlands andSweden.ResearchReport2459/Finland,ResearchReport2011:15/Sweden. NationalCouncilforCrimePrevention,NationalResearchInstituteofLegal Policy,UniversiteitLeiden.

HackerJSandPiersonP(2010)Winner-take-allpolitics:Publicpolicy,politicalorganization,andtheprecipitousriseinthetopincomesintheUnitedStates. Politicsand Society 38(2):152–204.

HeumannMandCassakL(2003) GoodCop,BadCop:RacialProfilingandCompeting ViewsofJustice.Berne:PeterLang.

HobbesT(1962) Leviathan.NewYork:Macmillan.

HuberE,RaginCandStephensJT(1993)Socialdemocracy,Christiandemocracy, constitutionalstructureandthewelfarestate. AmericanJournalofSociology 99(3): 711–749.

Junger-TasJ(1997)EthnicinequalitiesincriminaljusticeintheNetherlands. Crimeand Justice:AReviewofResearch 21:257–310.

KaganR(2001) AdversarialLegalism:TheAmericanWayofLaw.Cambridge,MA: HarvardUniversityPress.

KatznelsonI(2005) WhenAffirmativeActionWasWhite:AnUntoldHistoryofRacial InequalityinTwentieth-CenturyAmerica.NewYork:WWNorton.

KingGandZengL(2001)Improvingforecastsofstatefailure. WorldPolitics 53(4): 623–658.

KingJD(2000)ChangesinprofessionalisminU.S.statelegislatures. LegislativeStudies Quarterly 25(2):327–343.

KingdonJ(1984) Agendas,AlternativesandPublicPolicies.Boston,MA:Little,Brown.

KleimanM(2010) WhenBruteForceFails:HowtoHaveLessCrimeandLess Punishment.Princeton,NJ:PrincetonUniversityPress.

LaceyN(2008) ThePrisoners’Dilemma:PoliticalEconomyandPunishmentin ContemporaryDemocracies.Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress.

LaceyNandSoskiceD(2013)WhyarethetrulydisadvantagedAmerican,whenthe UKisbadenough?Apoliticaleconomyanalysisoflocalautonomy,criminaljustice, educationandresidentialzoning.LondonSchoolofEconomicsWorkingPaper,11/ 2013.Availableat:http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id ¼2264749.

LaFreeG(2002)Toomuchdemocracyortoomuchcrime?LessonsfromCalifornia’s three-strikeslaw. LawandSocialInquiry 27(4):875–902.

LaneR(1989) RootsofViolenceinBlackPhiladelphia:1860–1900.Cambridge,MA: HarvardUniversityPress.

LauritsenJLandHeimerK(2010)Violentvictimizationamongmalesandeconomic conditions:Thevulnerabilityofraceandethnicminorities. CriminologyandPublic Policy 9(4):665–692.

LermanAEandWeaverVM(2014) ArrestingCitizenship:TheDemocratic ConsequencesofAmericanCrimeControl.Chicago,IL:UniversityofChicagoPress.

LevittSandDubnerSJ(2005) Freakonomics.NewYork:WilliamMorrow.

LijphartA(1999) PatternsofDemocracy.NewHaven,CT:YaleUniversityPress.

LoaderIandWalkerN(2007) CivilisingSecurity.Cambridge:CambridgeUniversity Press.

LowiT(1984)WhyistherenosocialismintheUnitedStates?Afederalanalysis. InternationalPoliticalScienceReview 5(4):369–380.

LynchM(2009) SunbeltJustice:ArizonaandtheTransformationofAmerican Punishment.Stanford,CA:StanfordUniversityPress.

ManzaJandBrooksC(2007) WhyWelfareStatesPersist.Chicago,IL:Universityof ChicagoPress.

MasseyDandDentonN(1993) AmericanApartheid:SegregationandtheMakingofthe Underclass.Cambridge,MA:HarvardUniversityPress.

MillerLL(2010)Theinvisibleblackvictim:HowAmericanfederalismperpetuates racialinequalityincriminaljustice. LawandSocietyReview 44(3/4):805–842.

MillerLL(2013)Powertothepeople:Violentvictimization,inequalityanddemocratic politics. TheoreticalCriminology 17(3):283–313.

MoosbruggerL(2012) TheVulnerabilityThesis:InterestGroupInfluenceand InstitutionalDesign.NewHaven,CT:YaleUniversityPress.

MurakawaN(2014) TheFirstCivilRight:HowLiberalsBuiltPrisonAmerica.New York:OxfordUniversityPress.

MurakawaNandBeckettK(2010)Thepenologyofracialinnocence:Theerasureof racisminthestudyandpracticeofpunishment. LawandSocietyReview 44(3&4): 695–730.

NivetteAE(ed.)(2011)‘‘Cross-nationalpredictorsofcrime:Ameta-analysis’’.Crossnationalpredictorsofcrime:Ameta-analysis. HomicideStudies 15(2):103–113.

ParkerCandBarretoM(2013) ChangeTheyCan’tBelieveIn:TheTeaPartyand ReactionaryPoliticsinAmerica.Princeton,NJ:PrincetonUniversityPress.

PetersonP(1981) CityLimits.Chicago,IL:UniversityofChicagoPress.

PetersonRDandKrivoLJ(2010) DivergentSocialWorlds:NeighborhoodCrimeand theRacial-SpatialDivide.NewYork:RussellSage.

PhillipsCandBowlingB(2012)Ethnicities,racism,crime,andcriminaljustice. In:MaguireM,MorganRandReinerR(eds) TheOxfordHandbookof Criminology.Oxford:UniversityofOxfordPress.

ProvineDM(2007) UnequalunderLaw:RaceintheWaronDrugs.Chicago,IL: UniversityofChicagoPress.

Rawls,John.1971. ATheoryofJustice.Cambridge,MA:HarvardUniversityPress.

RehmP(2011)Socialpolicybypopulardemand. WorldPolitics 63(2):271–299.

RikerW(1964) Federalism:Origin,Operation,Significance.Boston,MA:Little, Brown.

RobertsonDB(1989)ThebiasofAmericanfederalism:Thelimitsofwelfare-state developmentintheprogressiveera. JournalofPolicyHistory 1(3):261–291.

RothR(2009) AmericanHomicide.Cambridge,MA:HarvardUniversityPress.

RuthHandReitzK(2006) TheChallengeofCrime:RethinkingOurResponse. Cambridge,MA:HarvardUniversityPress.

SampsonR(2012) GreatAmericanCity:ChicagoandtheEnduringNeighborhood Effect.Chicago,IL:UniversityofChicagoPress.

ScheingoldS(1984) ThePoliticsofLawandOrder:StreetCrimeandPublicPolicy. NewYork:Longman.

SchlesingerT(2011)Thefailureofrace-neutralpolicies:Howmandatorytermsand sentencingenhancementsincreasedracialdisparitiesinprisonadmissionsrates. CrimeandDelinquency 57(1):56–81.

SchoenfeldH(2010)Massincarcerationandtheparadoxofprisonconditionslitigation. Law&SocietyReview 44(3/4):731–768.

SilversteinG(2009) Law’sAllure:HowLawShapes,Constrains,SavesandKillsPolitics. NewYork:CambridgeUniversityPress.

SimonJ(2014) MassIncarcerationonTrial.NewYork:NewPress.

SmithK,OsborneS,LauI,etal.(2012)Homicides,firearmoffencesandintimate violence2010/11:Supplementaryvolume2toCrimeinEnglandandWales2010/ 11.HomeOfficeStatisticalBulletin.

SoskiceD(2010)Americanexceptionalismandcomparativepoliticaleconomy.

In:BrownC,EichengreenBandReichM(eds) TheGreatUnraveling:NewLabor MarketInstitutionsandPublicPolicyResponses.Cambridge:CambridgeUniversity Press,pp.51–93.

SossJ,FordingRCandSchramSF(2008)Thecolorofdevolution:Race,federalism andthepoliticsofsocialcontrol. AmericanJournalofPoliticalScience 52(3): 536–553.

SquireP(2007)Measuringstatelegislativeprofessionalism:TheSquireIndexrevisited. StatePoliticsandPolicyQuarterly 17(2):211–227.

TonryM(2009)ExplanationofAmericanpunishmentpolicies. PunishmentandSociety 11(3):377–394.

WacquantL(2007) PunishingthePoor:TheNeo-LiberalGovernmentofSocial Inequality.Durham,NC:DukeUniversityPress.

WalmsleyWalmsleyR(2000) WorldPrisonPopulationList(SecondEdition).Research Findings,No.116.HomeOfficeResearch,DevelopmentandStatisticsDirectorate. London:InternationalCentreforPrisonStatistics.

WeaverVM(2007)Frontlash:Raceandthedevelopmentofpunitivecrimepolicy. StudiesinAmericanPoliticalDevelopment 21:230–265.

WeberM(2004) TheVocationLectures.Ed.OwenDandStrongTBandtrans. LivingstoneR.Cambridge,MA:Hackett.

WestHCandSabolWJ(2010) Prisonersin2009.BureauofJusticeStatistics;Officeof JusticePrograms.December,NCJ231675.Washington,DC:USDepartmentof Justice.

WesternB(2006) PunishmentandInequality.NewYork:RussellSage.

WhiteNandLauritsenJ(2012)Violentcrimeagainstyouth,1994–2010.Officeof JusticePrograms,BureauofJusticeStatistics,NJC240106.Washington,DC: DepartmentofJustice.

WildavskyAB(1984)Federalismmeansinequality:Politicalgeometry,politicalsociologyandpoliticalculture.In:FeslerJW(ed.) TheCostsofFederalism.Ed. GolembiewskiRTandWildavskyAB.NewBrunswick,NJ:TransactionPress.

ZednerL(2009) Security.NewYork:Routledge.

ZimringFEandHawkinsG(1997) CrimeIsNottheProblem:LethalViolenceIs. Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress.

ZimringFEandJohnsonDT(2006)Publicopinionandthegovernanceofpunishment indemocraticpoliticalsystems. AnnalsoftheAmericanAcademyofPoliticaland SocialSciences 605:265–280.

LisaL.Miller (PhD,1999,UniversityofWashington)isanAssociateProfessorof PoliticalScienceatRutgersUniversity.Herresearchinterestsareinlaw,social policy,inequality,crimeandpunishment.Hermostrecentbook, ThePerilsof Federalism:Race,PovertyandCrimeControl (Oxford,2008),exploresthe

relationshipbetweenthepeculiarstyleofUSfederalismandthesubstantial inequalitiesincriminalvictimizationandpunishmentacrossracialgroupsinthe US.Herworkhasappearedin LawandSocietyReview, PerspectivesonPolitics, CriminologyandPublicPolicy, PolicyStudiesJournal, LawandSocialInquiry, TheoreticalCriminology, TulaneLawReview,amongothers.Hercurrentbook project, TheMythofMobRule:ViolentCrimeandDemocraticPolitics,isacomparativestudyoftherelationshipbetweentheinstitutionalfeaturesofdemocratic systemsandthepoliticsofcrimeandpunishment.Sheisalsoworkingonaproject exploringhowconstitutionaldesignsstructurepoliticalopportunitiesformass publics.In2012–2013shewasaVisitingScholaratthePrograminLawand PublicAffairsintheWoodrowWilsonSchoolofGovernmentatPrinceton University.In2011–2012shewasVisitingFellowatAllSoulsCollegeatthe UniversityofOxford. 210