This research aims to analyze how to design, and spatially organize a new settlement to meet the present and future needs of excombatants in Colombia. Conducted through an ongoing participatory process and mutual aid approach, this thesis discusses the role of development beyond Housing, as it pertains to the livelihood of the inhabitants of Tierra Grata. This work is an important and timely contribution for researchers, policy, and decision-makers, as well as those who aspire and are committed to combating climate change and protecting the environment.

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Sustainable Human Habitats

The case of Tierra Grata, Cesar, Colombia

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam masohajesam@student.ethz.ch

The Role of Landscape Architecture

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

MAS ETH IN HOUSING 2021-2022 Thesis Nr. 137

MAS 137

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Sustainable Human Habitats

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam masohajesam@student.ethz.ch

MAS ETH IN HOUSING 2021-2022

Thesis Nr. 137

Supervisors:

Dr. Jennifer Duyne Barenstein Daniela Sanjines

Co-supervisors:

Prof. Hubert Klumpner Prof. Dr Christian Schmid

Acknowledgments

This research would not be possible without the guidance of my academic advisors, Dr. Jennifer Duyne Barenstein and Daniela Sanjines. Thank you both for your patience, flexibility, availability, and mutual excitement over the evolution of this work and for helping guide my ideas to fruition. Thank you, Luna D. Rodriguez Lopez, for your vision and attitude, and especially for being a supportive partner, friend, and personal translator during my time in Colombia--thankyoufordaringtodreamwithme.

My profound gratitude and appreciation to my entire family, especially my father, Dr. Derek Asoh Ajesam, and sibling, Malik Asoh, for editing and proofreading this text. To my partner, Fabian Meier, thank you for supporting me through the ups and downs of this research--I am eternally grateful. Many thanks to my friends at Tierra Grata for welcoming me into your community and trusting me to tell your stories to the best of my capacity.

Finally, I give thanks to Zanahary for the presence of all the above-mentioned and the accomplishment of this work.

The case of Tierra Grata, Cesar, Colombia

Abstract

This thesis aims to examine the role of landscape architecture in sustainable human habitats, in particular within the context of Tierra Grata, in the region of Cesar in Colombia. Through an analysis of identified problems, this thesis attempts to deepen our understanding of the role of the environment and the complexity of incorporating appropriate landscape elements and other necessary spatial infrastructures as response instruments for food security, climate change and the economic and environmental vitality of a settlement. Additionally, this research highlights the need for food-centered cities through the prioritization and protection of the community’s connection to nature and how it relates to the identity, livelihood, and quality of life of the inhabitants. Furthermore, this work explores how spatial planning can shape the transitory spaces between homes while improving user experience through the implementation of tree planting as a means for climatic comfort. This thesis concludes with a proposal in the form of a conceptual landscape master plan with the potential to be implemented through the support of a mutual aid action plan. Although the solutions are not restricted to the architectural discipline, it is recommended that they should be approached with a mindset of spatial equality for successful reconciliation and implementation.

Keywords: Peace-building, Reconciliation, Urban Agriculture, Landscape Architecture, Sustainable Habitats, Food Urbanism i

ii

Introduction

11.1 Research Questions

1.2 Research Methodology

1.3 Thesis Structure

2Beyond Housing: Landscape Architecture in Practice

2.1 The Origin and Evolution of Landscape Architecture 2.2 Trees, People and the Natural Environment 2.3 Cultural Landscapes and Environmental Movements 2.4 Conclusion

3 Urban Agriculture:A Review of Selected Case Studies

3.1 The Global Role of Urban Agriculture

The Politics of Food Justice in Colombia

The Food Urbanism Initiative 3.4 Conclusion

4The Case of Tierra Grata, Cesar, Colombia

4.1 Ciudadela de Paz: A New Settlement

The School of Architecture for Reconciliation

A Local Perspective: Conversations and Interviews

Challenges and Opportunities

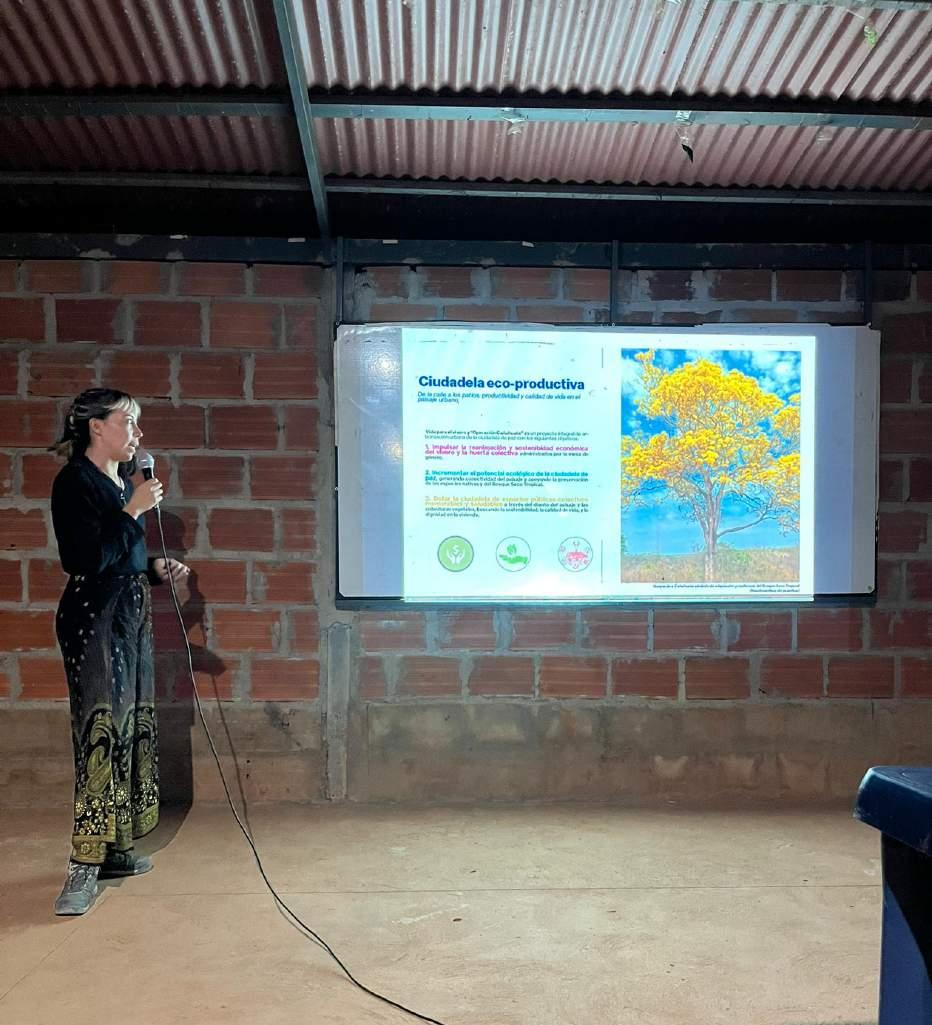

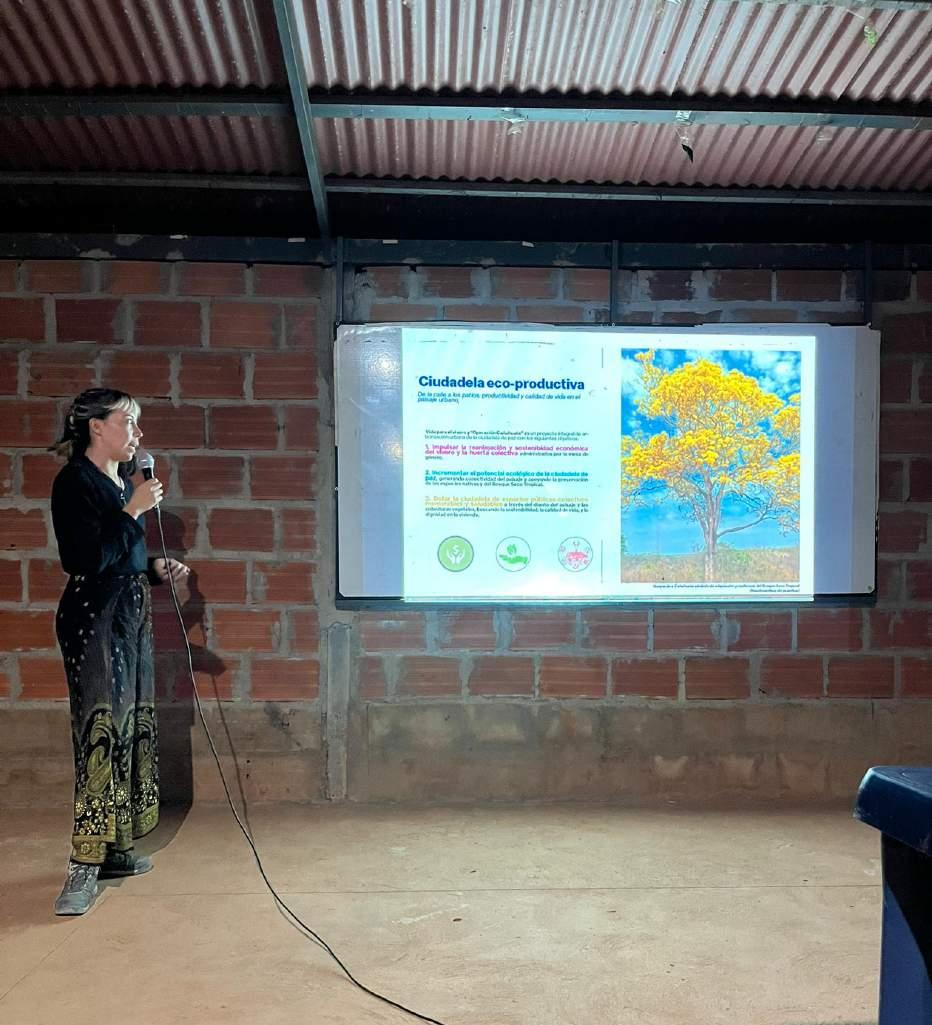

Operación Cañahuate: The Eco-Productive Citadel

Conclusion and Reflections

5.1 Limitations

Strategies for the Future

Bibliography

Appendix

List of Figures

List of Tables

List of Appendix

List of Acronyms

Preface

03 03 04

06 08 13 15

3.2

3.3

17 34 36 37

4.2

4.3

4.4

4.5

5.2

38 41 47 56 60 70 72 CONTENTS 76 69

iv vii vii viii xi 80

5

6

7

iii

Figure i. Cover page: Mango tree foliage in Valledupar, Colombia. Source: Marie Tina Asoh

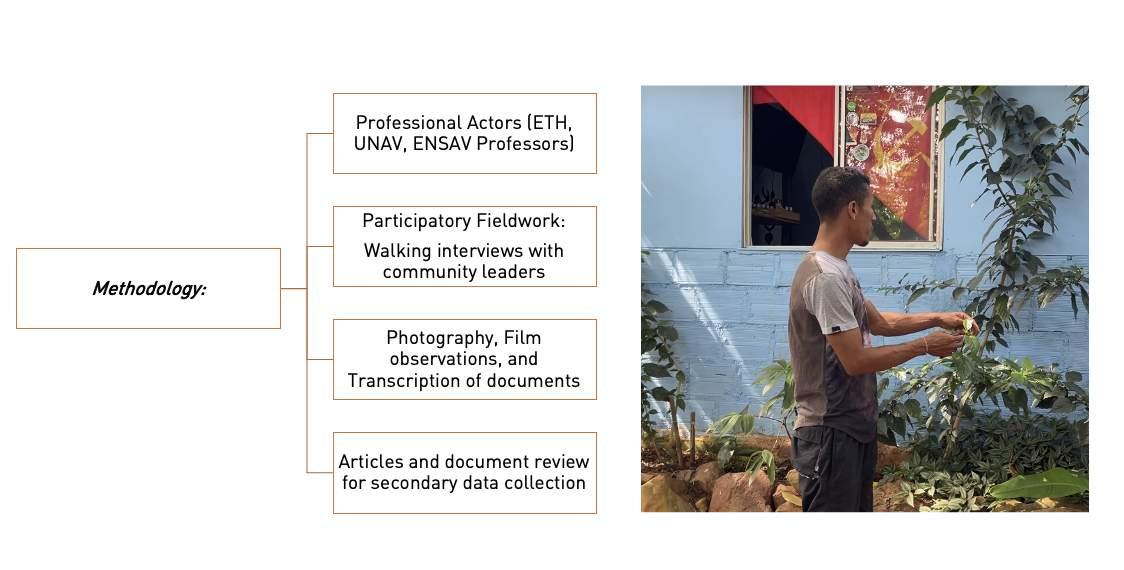

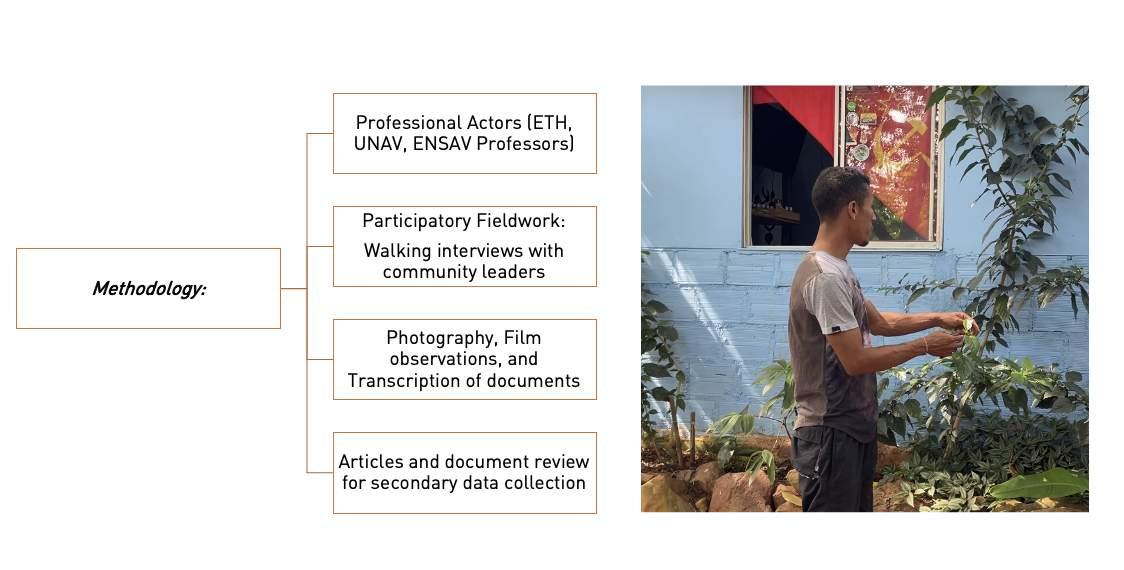

Figure 1. Methodology outline and image of Marco Guevara next to his living commune. Source: Marie Tina Asoh

Figure 2. The thesis structure summarized. Source: Marie Tina Asoh

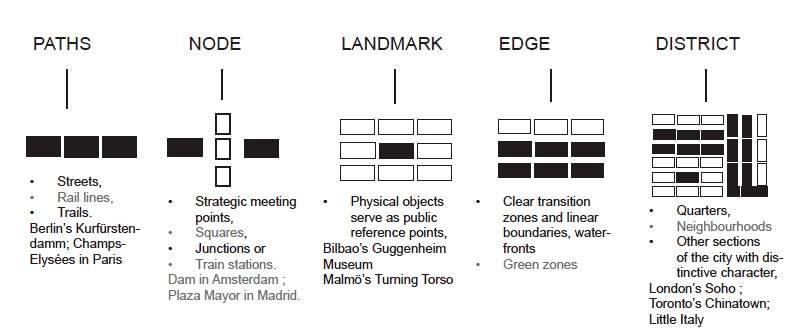

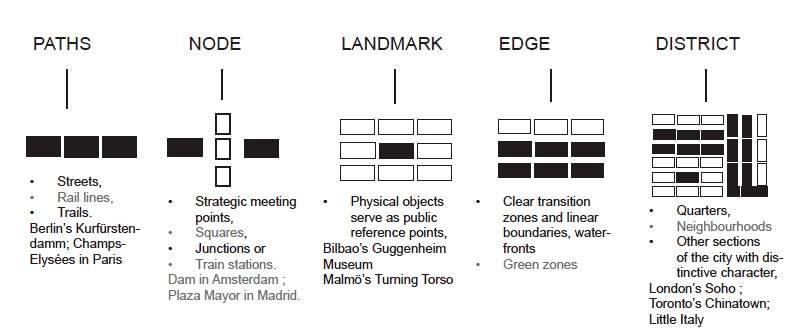

Figure 3. Image of five physical elements and components Source: Jojic, 2018

Figure 4. Aerial photo of Brønby Haveby, Denmark. © Henry Do.

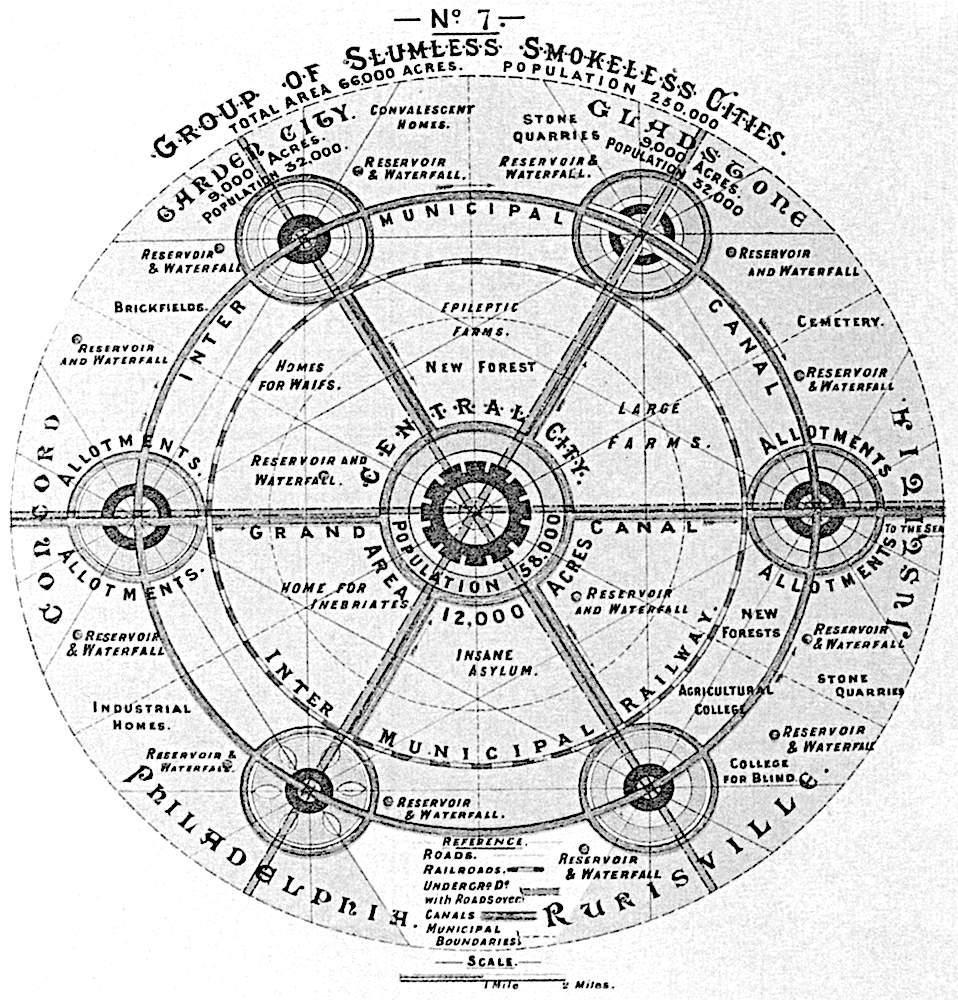

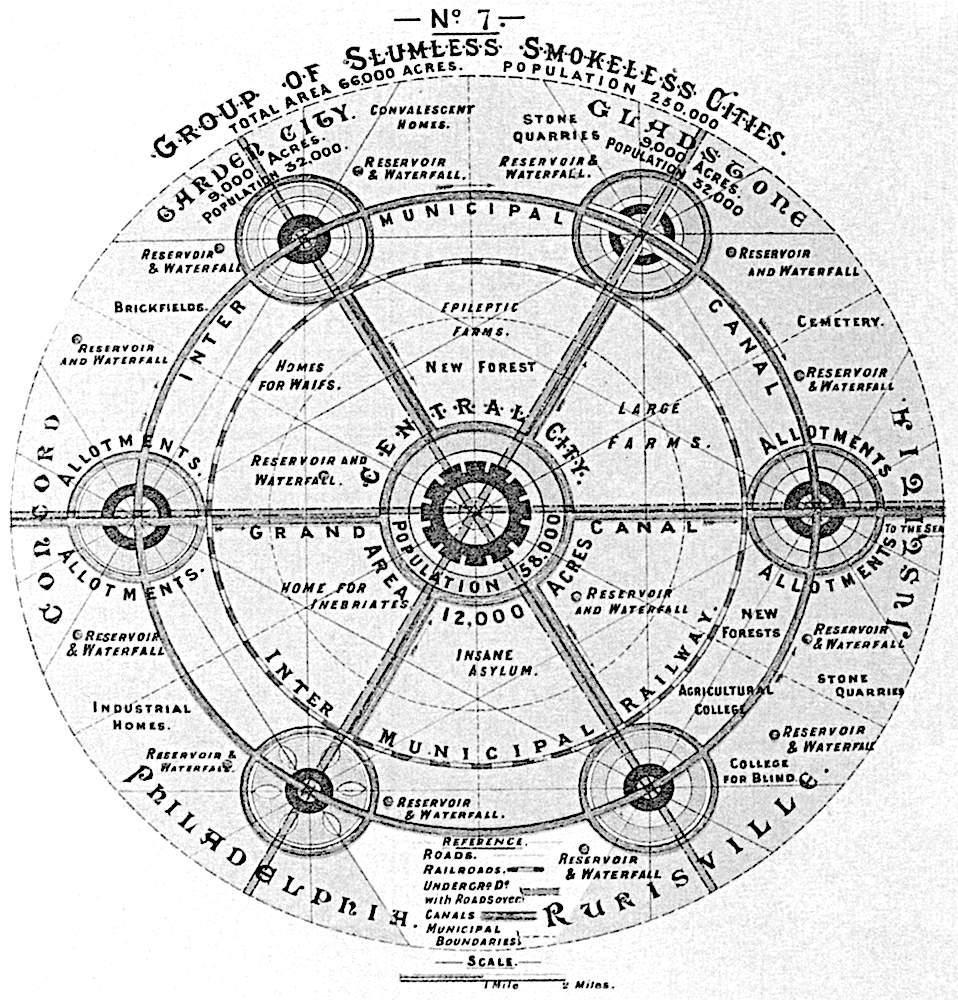

Figure 5: Garden City Map by Ebenezer Howard. Via Wikimedia Commons, public domain, 1902

Figure 6. Victory Garden posters from World War II. Office of War Information, National Archives (left) and Morley, War Food Administration (right) / Public Domain

Figure 7. Permaculture principles according to Bill Mollison. Source: The Seedling at Sagada, Australia

Figures 8 and 9. Women and children planting trees in Kenya. Source: The Green Belt Movement, 2020.

Figure 10. WMI Landscape Master plan. Source: Wangari Maathai Institute for Peace & Environmental Studies (WMI).

Figure 11. An urban agricultural farmer in Niayes Valley, Senegal. Source: Madeleine Bair.

Figure 12. Micro-gardening training centres in Dakar, Senegal. Source: Ms. Ndeye Ndack Pouye Mbodj.

Figure 13. View from TransMi Cable Car facing the top of Ciudad Bolívar. Source: Marie Tina Asoh

Figure 14. Context of Tierra Grata Source: School of Architecture for Reconciliation Reader (2022).

05 05 14 19 20 21 23 26 27 28 29 33 40 FIGURES iv

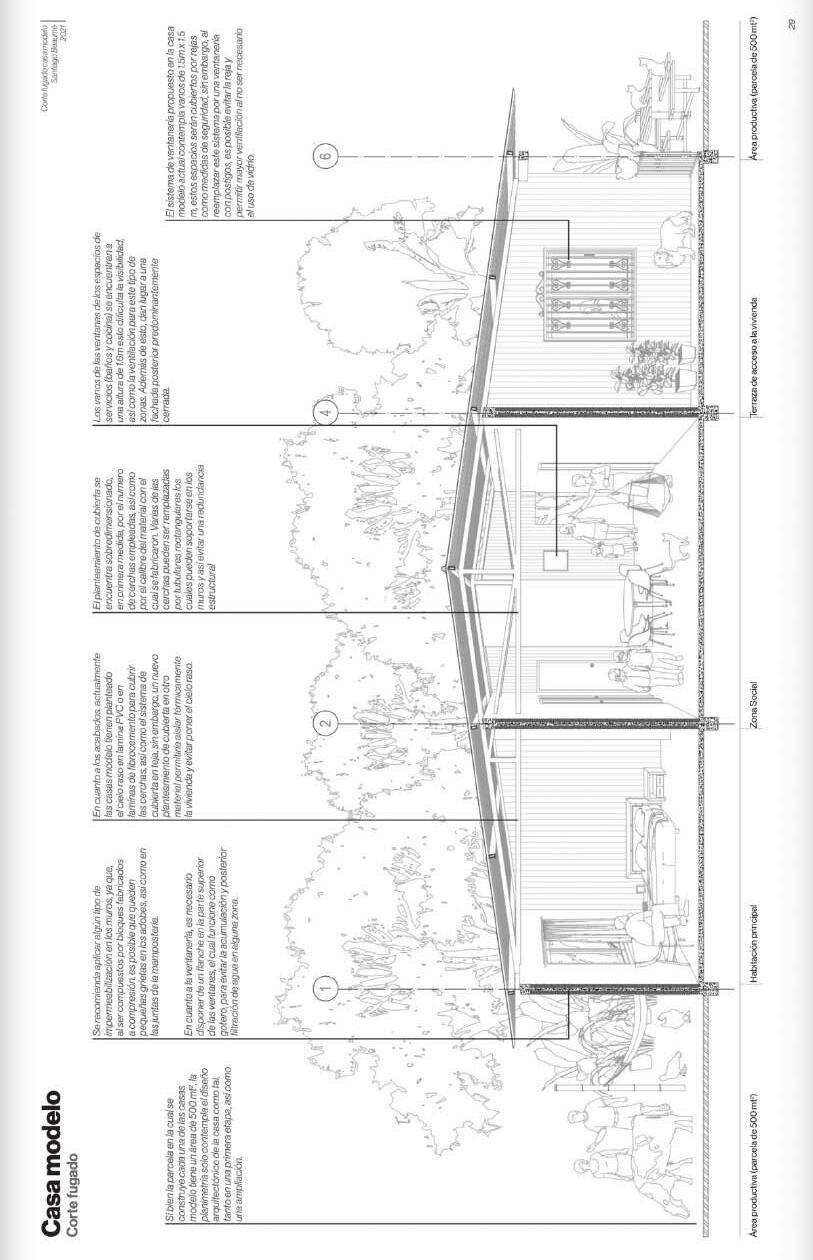

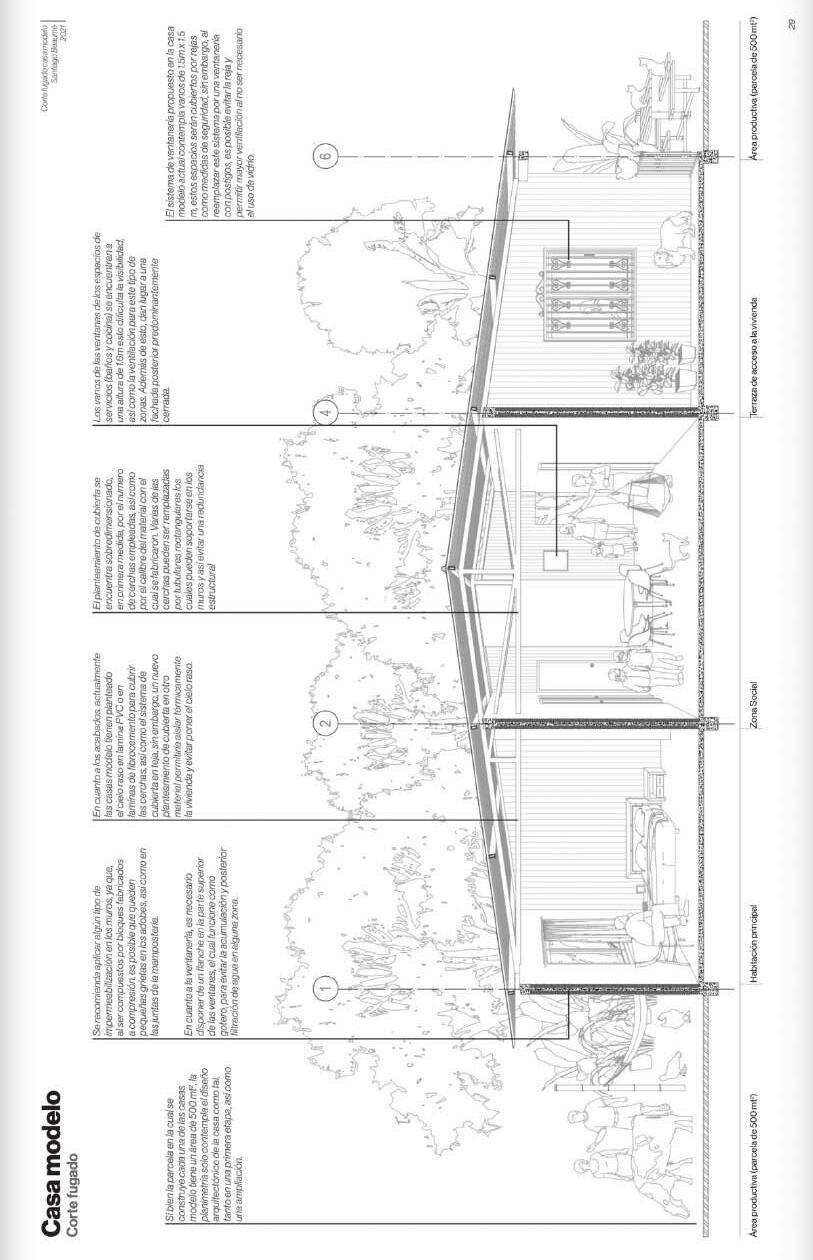

Figure 15. One of the prototype model houses built in Tierra Grata, a conceptual diagram of the model house available in Appendix B . Source: Tierra Grata.

Figure 16. Map of Ciudadela de Paz, Spatial Analysis, and Intervention Strategies sample from publication in collaboration with ENSA-V. Source: Paz y cooperativas de vivienda (2021) (Above)

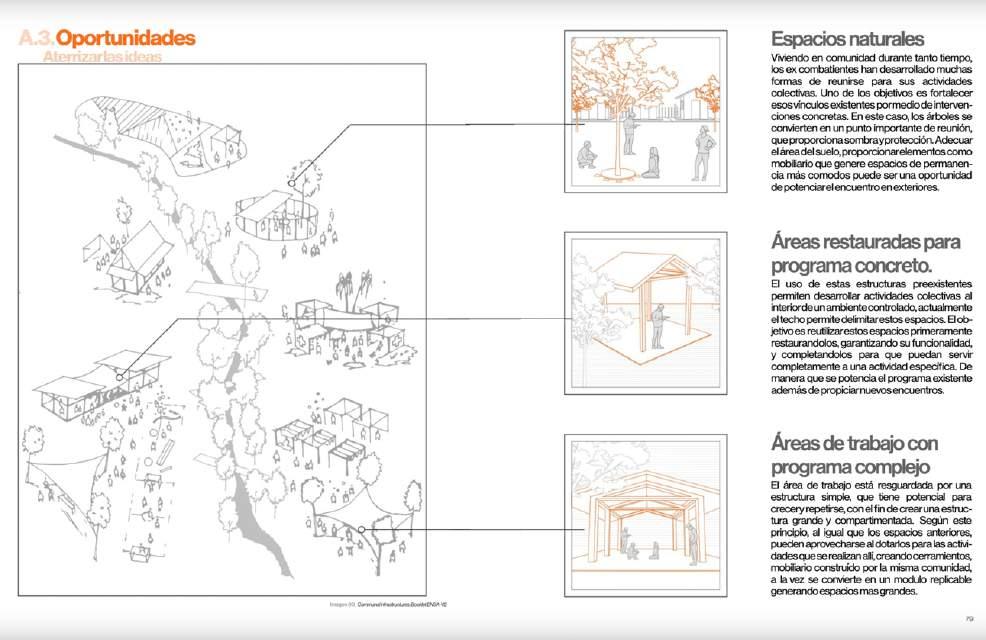

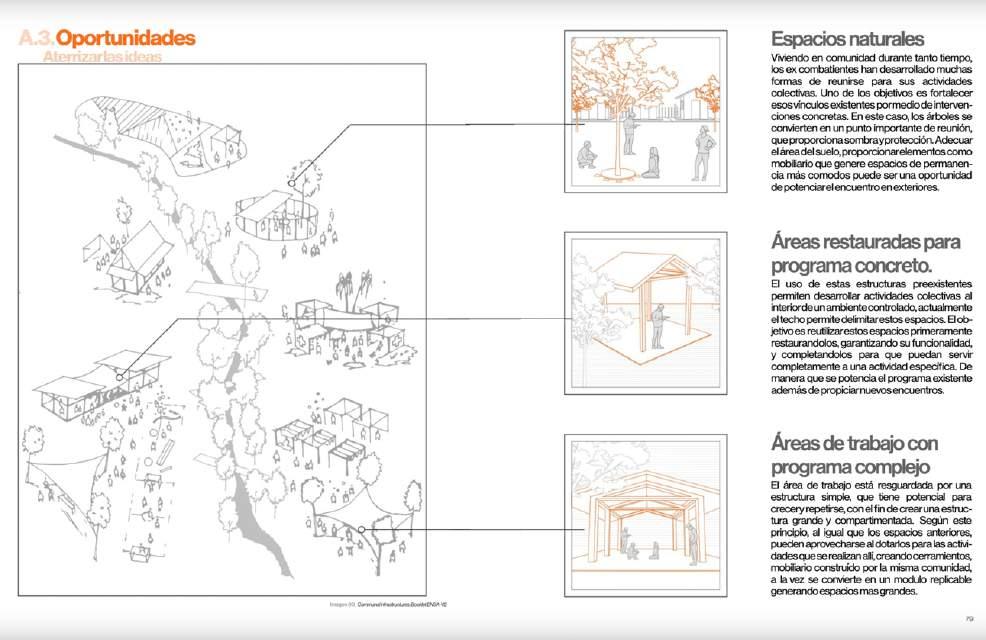

Figure 17. Map of Ciudadela de Paz, Spatial Opportunities, and Elements, a sample from publication in collaboration with ENSA-V. Source: Paz y cooperativas de vivienda (2021).

Figure 18. Vegetable gardens as a potential spatial element, including a variety of options in planting beds and typology. Sample from publication in collaboration with fellow students from ETH Zurich. Source: Paz y cooperativas de vivienda (2021).

Figure 19. Women and children from the community of Ciudadela de Paz, Tierra Grata, Source: Luna D. Rodriguez Lopez.

Figure 20. Orly and Luna walk towards the development plots. Source: Marie Tina Asoh

Figure 21. An example of how inhabitants mark their plot boundaries while waiting for the horses to be built. Source: Marie Tina Asoh

Figure 22. Antonio showed us the stock of quick stick trees, (Gliricidia sepium) often used for making fences due to their fast growth rate. Source: Marie Tina Asoh

Figure 23. (Above) Marco showing us a photo of his property, in 2016 when he first arrived, versus

Figure 24. (Below) him standing in the same spot today, illustrating his commitment to re-greening his new settlement. Source: Marie Tina Asoh

Figure 25-26. Luna discusses with local construction workers about future development on the new site, as they demolish trees to make way for a new settlement (below). Source: Marie Tina Asoh

FIGURES

40 43 44 46 47 50 50 51 53 53 55 v

Figure 27. A visual indication of opportunities and constraints of the new and current site (continued on the following page) Source: Marie Tina Asoh

Figure 28. ETCR Tierra Grata in context to the new settlement. Source: Tierra Grata Official

Figure 29. Google base map of settlement site and digitalized settlement master plan for Tierra Grata. Source: Tierra Grata Official Website

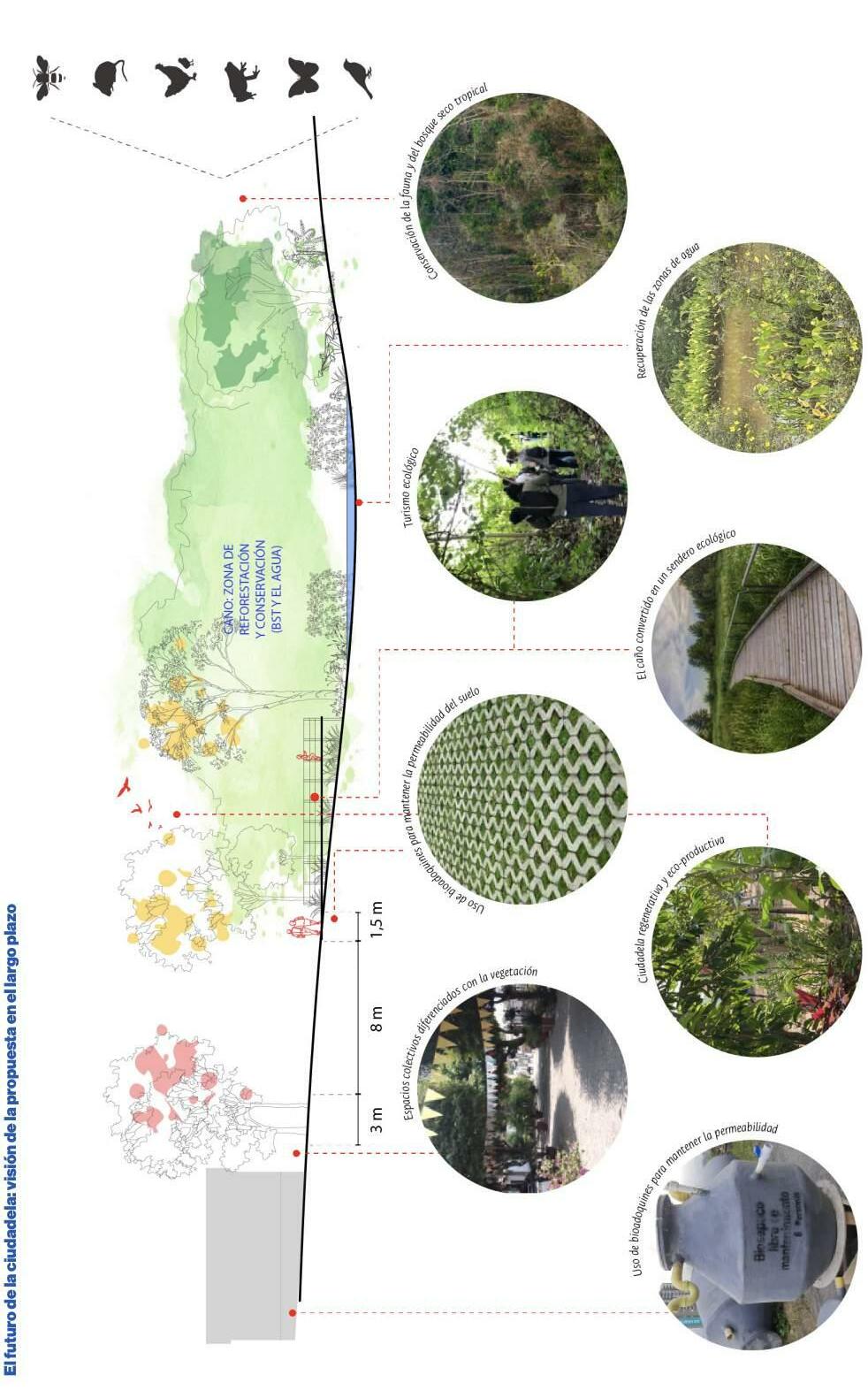

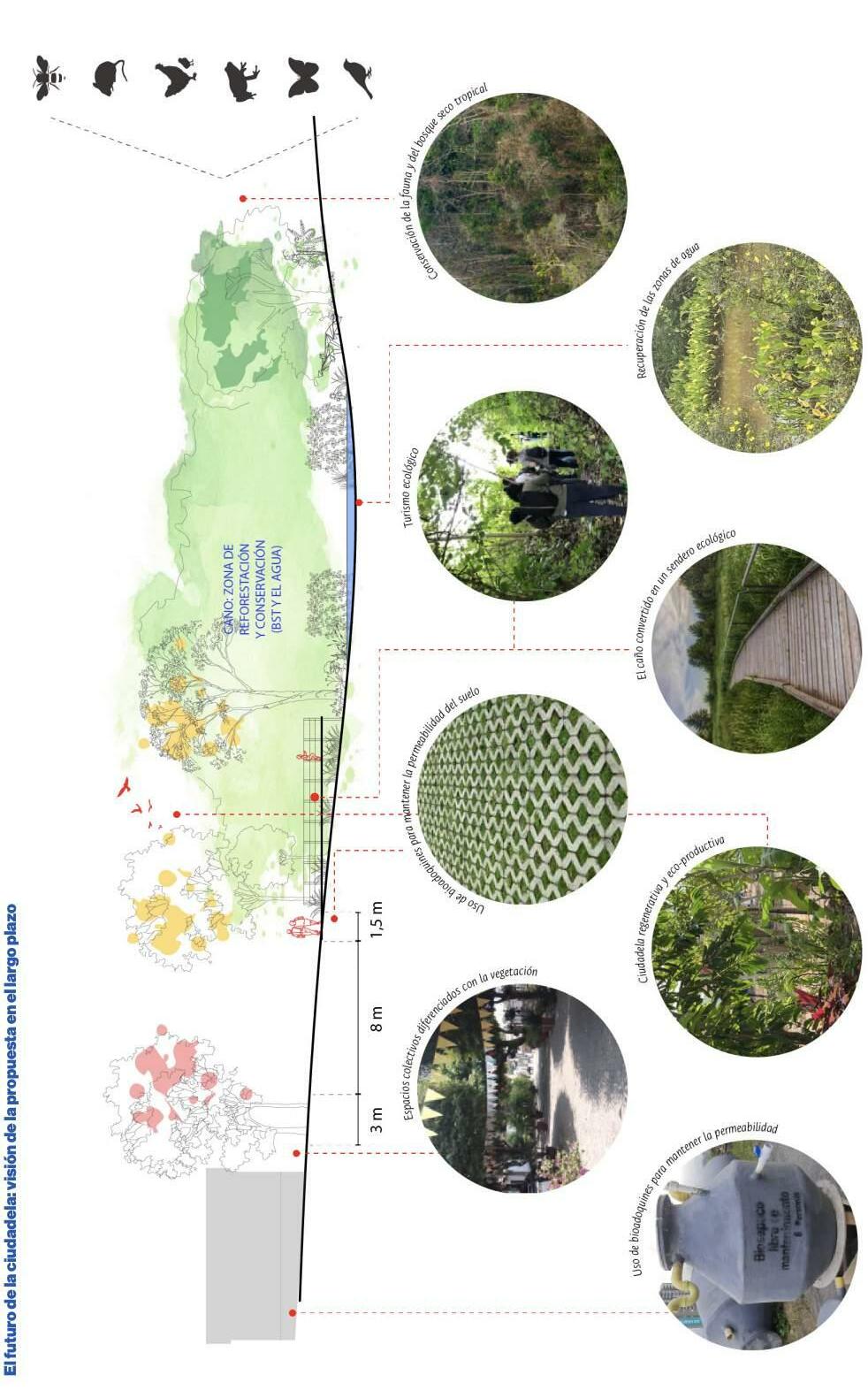

Figure 30. A conceptual master plan and coordinated action plan for Ciudadela de Paz, also referenced in Appendix F. Source: Marie Tina Asoh and Luna D. Rodriguez Lopez

Figure 31. An example of a mango tree in an urban setting, providing shade and influencing the microclimate in Valledupar. Source: Marie Tina Asoh

Figure 32. A conceptual cross-section through the site for Ciudadela de Paz which appears in better quality in Appendix G. Source: Marie Tina Asoh and Luna D. Rodriguez Lopez

Figure 33. Above: Luna identifying local plant specifies for the inventory list. Source: Marie Tina Asoh

Figure 34. Below: The current state of the nursery roof, which needs to be replaced as part of the action plan. Source: Marie Tina Asoh

Figure 35. Luna presented our Tree-planting initiative and master plan concept to the community. Source: Daniela Sanjines

Figure 36. The ETH and UNAV Group, including teachers and working guests from the School of Architecture for Reconciliation, posed in front of one of the prototype houses, which we utilized as our “working quarters” for the week. Source: Daniela Sanjines

FIGURES

56 58 59 61 64 66 67 67 68 71 vi

Table 1. City Dimension and the Role of Landscape Architect Source: Yang, 2022

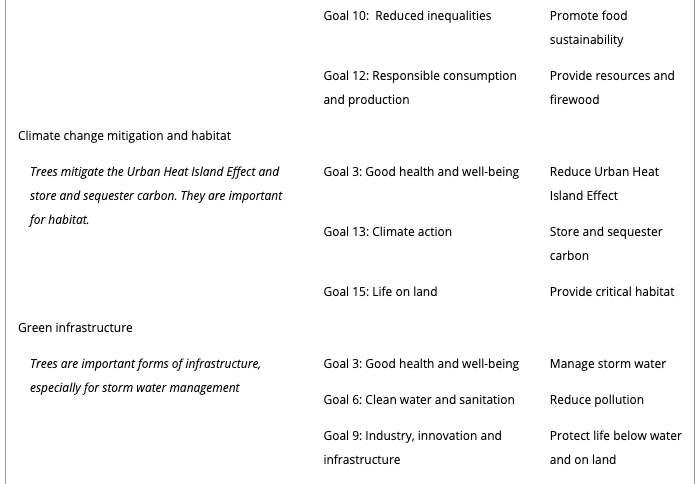

Table 2. The benefit of urban trees and corresponding SDGs. Source: Turner-Scoff, 2019

Table 3. Relationship among the principles of urban quality. Source: Verzone and Woods, 2021

Table 4. Criteria for evaluation within the FUI. Source: Verzone and Woods, 2021

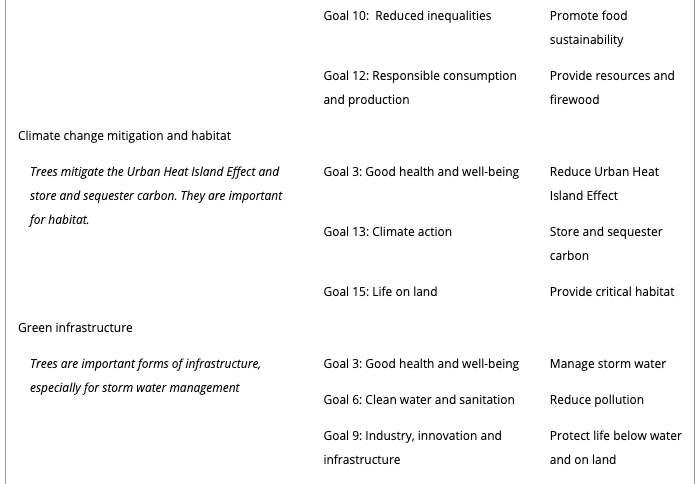

Appendix A: The Benefit of urban trees and corresponding Sustainable Development Goals continued. Source: Turner-Scoff, 2019

Appendix B: Prototype of the model house designed for Tierra Grata’s new settlement. Source: Paz y cooperativas de Vivienda 2021.

Appendix C: Site photos of Tierra Grata. Source: Marie Tina Asoh

Appendix D: A cultural meeting point at the center of the commune. Source: Marie Tina Asoh

Appendix E: Housing typologies and cultural landscape elements at Tierra Grata. Source for the above photos: Marie Tina Asoh. Source for the photo below: Tierra Grata’s Official Website

APPENDIX F: Zoom in on the conceptual master plan. Source: Marie Tina Asoh

Appendix G: Conceptual cross sections of the chosen site. Source: Luna D. Rodrigues Lopez

Appendix H: Inventory of Plant Nursery, March 2022. Source: Marie Tina Asoh and Luna D. Rodrigues Lopez

TABLES / APPENDIX

07 12 73 73 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 88 vii

BTC / CEB Compacted Earth Blocks

CIESIN Center for International Earth Science Network

CONFECOOP Confederation of Colombian Cooperatives

ENSAV National School of Architecture of Versailles École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Versailles

EPRS European Parliament Research Services

ETCR Territorial Spaces for Capacity Building and Reincorporation

FAO Food and Agriculture Organization

FARC Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (People’s Army) Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (Ejército Del Pueblo)

FUI Food Urbanism Initiative

IDRC International Development Research Canada

PSF Project without Borders Fundacion Proyectar Sin Fronteras

PUA Peri-Urban Agriculture

RTF Right to Food

SDG Sustainable Development Goal UA Urban Agriculture UN United Nations

UNAL The National University of Colombia Universidad Nacional de Colombia

UPUA Urban-/Peri Urban Agriculture

WMI Wangari Maathai Institute for Peace & Environmental Studies

ACRONYMS

viii

ix

x

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

PREFACE

According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN Habitat), habitat is defined as “the locality in which a plant or animal naturally grows or lives. It can be either the geographical area over which it extends, or the location in which a specimen is found” (UNEP, 202therefore the places where people live are called the human habitat, including environments in which they sleep, eat, and often work (SIEM, 2006).

As someone who grew up on the constant move, I have borne witnessed, experienced, and participated in a variety of human habitats. From being born in Cameroon to spending my early years in the United States, and even briefly living in Botswana before “settling” in Canada for my adolescent years, I am most familiar with the feeling of searching for a place to call home. When people ask me where I am from, I often hesitate to answer, because I have never felt like I am from one place in particular; rather an accumulation of the places I have had the opportunity to live in. Through my parents’ career opportunities, my family was constantly on the move which offered us an opportunity to experience and be part of various social, cultural, and of course, political environments. Through these experiences, what stuck with me the most was always the spatial qualities (and inequalities) of the environments I lived in. As a result of my parents, particularly my father, being offered the opportunity to teach as a professor at various universities, we often saw it as a good thing, an opportunity for growth, for change. As a child, however, you may struggle with change, especially when it is not your choice, and especially when there are added layers of political changes and other events beyond your comprehension (such as understanding the preoccupation of the inhabitants in the locality you find yourself within)

These were my exact sentiments as I began my journey traveling into the commune of Tierra Grata, Ciudadela de Paz, (the Citadel of Peace), in the region of Cesar, Colombia in March of this year (2022). I imagined how the children currently in this commune came to be where they are, how their parents had little to no say in where they would be, but rather settled there as a response to a necessity, to meet their livelihood and housing needs within their capacity. During the time I spent in Colombia, I visited the towns/cities/localities of Bogota, Valledupar, Tierra Grata, and Barranquilla, I was able to witness the disparity in access to not only well maintained public spaces and parks, but also the spatial development of neighbourhoods and community spaces, especially for those who could not choose where they settled, such as refugees, immigrants, low income families, and of course, ex combatants among other

xi

vulnerable populations. Through these personal experiences, I came to realize that regardless of the country, access to housing, especially close to quality public spaces is a concept reserved for the “privileged” based on how different governments incorporate (or fail to incorporate) adequate and sustainable spatial planning for these vulnerable communities. In a physical sense, I could see how different cities or neighbourhoods were spatially designed to influence who has access to a place in terms of proximity and safety, in line with an analysis in a recent New York Times article:

“In poorer neighbourhoods, residents have access to 21 percent less park space than those who live in high income areas, the Trust for Public Land analysis found. The disparity is deeper along racial lines: Those in neighbourhoods that are home to people of color have access to 33 percent less park space than people in largely white areas.” (Closson, 2021)

This percentage applies to New York, but when we look at other cities, states, and even countries, it becomes clear how relevant the theme of disparity is prevalent. Spatial planners, landscape architects, and architects alike, therefore, have a role, or rather a responsibility in ensuring that the planning of new settlements is carried out with a balanced view alongside its inhabitants. This will further ensure that there is a more human inclusive and sustainable approach to development, especially within the sensitive context of peace building and reconciliation as is the case in Colombia. With the political and environmental climate of the world today, we can each only do our part to take care of the environment that takes care of us. The aim of this work is therefore to evoke a sense of urgency, and responsibility among all of us, including you, dear reader, so we can all do our part in forming the ideal community in which our habitats can be sustained and meet not only our needs but the needs of future generations.

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Sustainable Habitats

xii

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

xiii

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Sustainable Habitats

xiv

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

1. INTRODUCTION

On November 24th, 2016, a peace treaty was signed to signal an end to the armed conflict between the National Government of Colombia and the largest guerrilla group, FARC EP (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia Ejército Del Pueblo). The goal of this peace treaty was to build stable, long lasting peace and end the forced displacement of millions of Colombian men, women, and children victims of the armed conflict (Barenstein and Sanjines, 2022). Many communities were greatly affected by the conflict, from urban to rural communities, including Indigenous people, political parties, and economic associations. As a result, this peace treaty poses challenges for communities affected by the conflict as well as ex combatants in the process of reincorporation to access adequate housing and livelihood opportunities. For all those affected by the armed conflict, the right to protection is sacred to them, equally as the access to their Indigenous lands. However, even with the peace treaty signed, the aftermath of the crisis is far from being resolved.

As the Government of Colombia has been unable to provide long term viable solutions, housing continues to remain an issue for those affected. Re integrating approximately 10,000 ex combatants back into the system as war veterans is mandatory and is perhaps the greatest of the challenges; there is a dire need for an alternate approach to address basic housing needs for them and the others affected. As part of the peace negotiation process, the ex combatants received an opportunity to “reintegrate as a means to maintain their identity and social cohesion” (Barenstein and Sanjines, 2022) which led to the creation of 24 temporary camps as a means of housing. The relocation of the ex combatants into temporary camps, referred to as “Territorial Spaces for Capacity Building and Reincorporation” (ETCR), included a total of up to 3,000 ex combatants as inhabitants (Barenstein and Sanjines, 2022). These spaces were intended to be transitory; however, their legal status expired as of August 2020, highlighting once again the reality of post conflict realities: the lack of long term solutions for adequate housing and sustainable habitats. A long term solution to territorial peace is undoubtedly attainable through a combination of architectural, anthropological, and landscape architectural approaches applied in assessing the built environment and creating solutions that can be integrated as part of a community's rural/urban development plan.

1

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Human Habitats

To date, the housing commune of Tierra Grata continues to work towards peace building and reconciliation by reimagining their ideal settlement. The community came together and pulled their resources to buy land adjacent to their ETCR to develop a housing cooperative project inspired by the Uruguayan Mutual aid Housing Cooperative Model. This approach, with fervently hope would meet not only their immediate needs but also the future needs of their families and off springs (Barenstein and Sanjines, 2022). Through receiving support from local and international academic and non academic institutions and organizations, they have succeeded in advancing the development of their vision, as they have begun constructing their homes. However, there remains a need to plan for and design communal spaces, for a community seeking to not only maintain but also reclaim their collective identity. To do so, it is imperative to address challenges that go beyond the four walls of a housing unit. Beyond housing, one of the main components that need to be urgently addressed is the development of a master plan that prioritizes forest and landscape conservation for sustainable development.

This component addresses three distinct needs:

• food security and urban agriculture as a source for individuals’ livelihood opportunities,

• an environmental protection plan in which a housing development project can be constructed while conserving the sensitive state of the immediate ecological context, and

• an urban forest and spatial plan to ensure qualitative public spaces that can provide immediate climatic comfort for the current and future residents of the commune.

2

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

1.1. Research Questions

Through the development of an action research project carried out over the last two years, this thesis aims to answer the following question: How can landscape architectural practices aid in improving the sustainability of human habitats, while fostering community cohesion and supporting peace and reconciliation?

The following sub questions are examined:

1. How can urban agriculture projects contribute to food security and enhance community development?

2. What are some examples of urban agriculture globally and in Latin America?

3. How can landscape architecture and urban agriculture support the collective reincorporation of ex combatants in Colombia?

1.2. Research Methodology

This research was conducted within the years 2021 2022 using a combination of qualitative and case study research methods, outlined in Figure 1 on page 5. The first phase of the qualitative research focused on secondary data collection and analysis. This was attainable through the revision of academic papers, policy documents, reports, presentations, and articles on landscape architecture, food security, urban agriculture, and community development. The secondary data collection process was enhanced by the review of reports of selected case studies around the world; the analysis of the qualitative data from the first phase provided pointers for the second phase. The second phase of the research project was a case study of the housing commune Tierra Grata, in Cesar, Colombia. The case study research was conducted within the framework of two seminar weeks of the “School of Architecture for Reconciliation: Knowledge Exchange and Production of Mutual Aid Housing Cooperatives for Peace” with the community of Tierra Grata. The accumulation of primary data was done through a week long field study where semi structured interviews were conducted with four prominent community leaders and residents within the community, as well through photographs, films observations in the field, and hands on collaboration with students of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia (UNAL).

3

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Human Habitats

1.3. Thesis Structure

This thesis is organized into five chapters, including this introduction, as depicted in Figure 2 on the following page. Chapter two outlines the analytical framework used by defining the role of landscape architecture, and how it pertains to development, especially regarding spatial quality and sustainable human habitats. Chapter three reviews various precedents reported in the literature to better understand the current state of research on urban agriculture in the Global North and South. Multiple scales of urban agriculture (UA) and how the definition and implementation of UA manifest differently in different contexts are examined. Through the introduction of the Food Urbanism Initiative (FUI) as a planning initiative and analytical framework, this chapter concludes with a discourse on food centered community development. Chapter four focuses on the context of Tierra Grata highlighting the background and context for the case study research. This chapter further presents the School of Architecture for Reconciliation and my contribution to the program within the last two years; this includes a summary of the interviews and analyses conducted, which helped to inform the final project proposal which may be eventually implemented within the Ciudadela de Paz

Commune. Finally, Chapter five concludes with reflections on experiences within a participatory workshop model over the past two years, suggestions for future research, strategies, and recommendations that other ECTRs can learn from and apply to their development endeavors and social activities.

4

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

5

Figure 1. Methodology outline and image of Marco Guevara next to his living commune. Source: Marie Tina Asoh

Figure 2. The thesis structure summarized. Source: Marie Tina Asoh

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Human Habitats

2. BEYOND HOUSING: LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE IN PRACTICE

This chapter reviews the role and evolution of landscape architecture as presented in various scholarly works. The objective is to contextualize the prevalent approaches to urban agriculture (UA) and landscape masterplans with emphasis on the context of trees as a necessary spatial element within any given landscape.

2.1. The Origin and Evolution of Landscape Architecture

In 1828, Gilbert Laing Reason first coined the term landscape architecture in his book on the Landscape Architecture of Great Painters in Italy (Murphy, 2016). The term ‘landscape architect’ was first used as a professional title by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in the context of their work on New York’s Central Park in the mid nineteenth century (Murphy, 2016). Furthermore, the term became further popularized through the formation of the American Society of Landscape Architects in 1899, which reflects the extensive history in which the landscape architecture field developed (Murphy 2016). According to academic scholar Michael D. Murphy (2016),

“…The purpose of landscape design is twofold: to guide change in the form of the landscape to create and sustain useful, healthful, and engaging built and natural environments; and to protect and enhance the landscape’s intrinsic cultural, ecological, and experiential qualities. The primary role of landscape architecture is to organize the complexity of the landscape into comprehensible, productive, and beautiful places to improve the function, health, and experience of life. To do this effectively, design practitioners need to understand the landscape and the ways people interact with it, and to apply effective design process and implementation methods.”

Meanwhile according to Anne Whinston Spirn in her 2001 publication, “The Authority of Nature: Conflict and Confusion in Landscape Architecture” she states:

“…The roots of landscape architecture lie in several constellations of disciplines: agriculture (gardening, horticulture, forestry); engineering; architecture and fine arts; science (ecology)...(...) Ecology as a science (a way of describing the world), ecology as a cause (a mandate for moral action), and ecology as an aesthetic (a norm for beauty) are often confused and conflated.”

It is therefore evident that during the last two decades, scholars agree that the role of landscape architecture has remained constant in its need to solve problems while evolving beyond the design of simple aesthetically pleasing landscapes. The definition of landscape architecture has evolved to form a design discipline in which understanding the landscape and being able to shape it has become its primary goal. As a profession, the role of landscape architecture aims to offer site planning, design, as well as management advice to improve the character, quality, and user experiences of the landscape, especially within the context of human settlement and activities (Murphy, 2016). Through intentional design, we can change

6

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

our landscapes to improve our overall human and environmental conditions, which is a role that landscape architects have been able to assume and evolve within. As landscape architecture has always been generally rooted in garden design, its capacity encompasses places such as parks, neighborhoods, and spaces in between. In contrast to urban planners, landscape architects usually focus on a site specific scale rather than a larger urban context (although it is not a restriction), to realistically design, plan, manage and implement their work within the built environment (Yang, 2022). This discourse empowers and challenges landscape architects to not only act as designers but as environmental stewards since they use spatial typology and urban form to shape how we interact with our built environment. Of course, the role of landscape architects varies depending on the scale on which they are designing as visible in Table 1.

Landscape design and planning aim to tackle various challenges from an urban to the regional level, which encompasses the idea of “think globally, act locally” (Nickayin, 2022). This concept tackles the challenge of designing and planning for an urbanizing planet, through an ecological approach which is what landscape architecture offers as a solution. Additionally, understanding how to utilize landscape architecture should include incorporating infrastructure, (re ) greening, food production, water system management, and transportation planning (Nickayin, 2022).

The concept of designing an environmentally friendly city is not new, as it relates to how humans occupy space in their habitats and prioritize (or neglect) their environment, resulting in “a city that is (directly) friendly to the surrounding environment, in terms of pollution, land

7

Table 1. City Dimension and the Role of Landscape Architect. Source: Yang, 2022

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Human Habitats

use and the alleviation of global warming, essentially an ecologically healthy city that seeks harmony with nature based on ecological principles” (Yang, 2011). The severe impacts of climate change on cities and human settlements call for a different approach to preserve, conserve and restore the environment to remain sustainable for future generations. Yang (2011) uses the Climate Friendly Park Program in the United States as one of the many approaches to “pollution free landscape architecture that helps decrease or eliminate greenhouse gas emissions, alleviate flooding associated with storms, and precipitation extremes by providing landscape infrastructure that can adapt to ecosystem changes resulting from climate change.” In summary, based on existing literature the role of landscape architects becomes one of environmental stewardship and should be urgently directed towards designing for and coping with the severe impacts of climate change on cities and human habitats.

2.2. Trees, People, and the Natural Environment

“Trees have a very deep and crucial meaning to human beings. The significance of old trees is archetypical; in our dreams, they often stand for the wholeness of personality. The trees people love, create special places; places to be in and places to pass through. Trees have the potential to create various kinds of social places (p. 798).”

Alexander et al. (1977)

Trees and nature are seen as a necessary and cultural aspect of any human habitat. For this reason, trees and other natural features continue to play an influential role in community and landscape development, as they evoke familiarity, a sense of place, feeling of cultural identification, as well as promote a sense of belonging which improves people’s livelihood and well being (Elmendorf, 2008). Additionally, Kaymar (2013) further affirms that “place identity is an important dimension of social and cultural life in urban areas,” as it plays a role in environmental psychology, especially within a conflict prone landscape. The immediate environment of any given community influences its cultural identity and sense of place. In particular, the role of trees in the landscape has always possessed a deeper symbol for Indigenous communities globally, especially those in more extreme climates such as Colombia where access to a healthy tree canopy system is seen as a n ecessity that can help not only humans, but fauna thrive in response to climatic comfort. Nevertheless, the natural environment holds a deeper role when there exists a complex relationship between the people and their environment such as the ex combatants having habituated the rainforests of Colombia as a form of temporary shelter, safety, and housing relief during the previously ongoing conflict. The linkage of Colombia’s rainforests to the survivors of the armed conflict

8

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

highlights the importance and necessity for the need to preserve their environmental connection and prioritize environmental protection, especially when it comes to expanding development projects (especially when doing so can foster a deeper connection to their community and strengthen their collective identity).

Various scholars support the promotion of trees, and tree planting initiatives to deepen a community’s relationship with its environment. For example, Greider and Garkovich (1994) argue that landscapes can be “the symbolic representation of a collective local history and the essence of a collective self definition.” In other words, the preservation of trees in ecologically sensitive areas can act as a means of revolution, as it pertains to cases of environmental opportunities or conflicts which can be especially critical when there is a lack of trees, as is often the case in areas that practice unregulated slash and burn agricultural techniques. Trees, parks, and other components of the natural environment are not perceived as stand alone concepts by those who depend on them but rather as social symbols that can define a social group, such as a neighbourhood, or even a courtyard. Considering the landscape in such a context is important because it essentially shapes the quality of space and extends into social functions such as family, home, love, health, and equality, just to name a few (Appleyard 1979).

Culturally, our relationship with the environment influences what we choose to protect and preserve, especially in response to our growing population in the world today.

According to scholar Turner Scoff (2019), trees, therefore, play a critical role for people, and the planet as studies demonstrate that the presence of trees in our immediate environment is proven to improve one’s mental and physical condition, as well as is essential for climatic comfort in urbanizing centers. Trees are therefore necessary for the sustainable development of growing communities. Health and social well being are often linked to the accessibility to green infrastructure and are deemed by scholars as one of the important benefits of having a healthy ecosystem habitat (Turner Scoff, 2019). Existing literature highlight other benefits of trees such as being linked to aiding patients' recovery in hospitals (Ulrich, 1984), and reducing blood pressure and stress in research participants (Hartig, et. al., 2003; Jiang, et. al. 2015).

Additionally, residents living in proximity to trees and parks, “felt healthier and were proven to have fewer cardio metabolic conditions, than their counterparts (Kardan et al., 2015) which speaks volumes about the privilege and levels of class systems that further influence the role of trees within any given community.

9

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Human Habitats

Apart from health and social well being, trees play a huge role in mitigating climate change as the reduction of air pollution is one of the primary benefits of conserving our local trees (Turner Scoff, 2019). According to a 2016 report by the Center for International Earth Science Network (CIESIN) trees, when adequately incorporated into the built environment can reduce a city’s temperature by up to 9°C (CIESIN, 2016). This is especially relevant to major cities, which can ultimately determine the quality of human health and the increase in heat related health issues due to the Urban Heat Island Effect and its impact on heat waves (Ward et al., 2016). As a result, incorporating trees into the built environment can offer shade, and climatic comfort and even actively cool the air of cities to mitigate extreme temperature conditions (Turner Scoff, 2019). Not only do trees possess benefits for people in their natural habitat, but it also plays a keystone role in terrestrial ecosystems (Manning, et al., 2006) which provide food and habitat for all flora and fauna, both improving and maintaining the biodiversity necessary for a sustainable habitat (Turner Scoff, 2019). Furthermore, trees in this context can be seen as “decentralized green infrastructure”, and play an important role in managing water, especially in an urban ecosystem (Berland, et al., 2014).

In 2019, the Water Infrastructure Improvement Act was enacted by Congress. Green infrastructure was defined as “the range of measures that uses plant or soil systems, permeable pavement or other permeable surfaces, or substrates, such as stormwater harvest and reuse and reduce flowers to sewer systems or surface waters” (US EPA, 2019). Due to the variance in climates, there is an emphasis on the importance and quality of proper tree selections, and local trees are identified to aid in adapting to and being resilient in unfavorable conditions and climates (Turner Scoff, 2019). The role of green infrastructure becomes necessary in collecting and integrating stormwater drainage where trees are planted, which means water accessibility and availability must be considered to adequately incorporate trees as a means of green infrastructure (Turner Scoff, 2019). As a result, the inequality of tree distribution within and among cities can be highlighted, due to the lack of proximity and accessibility. According to Scholars, studies in the last decade illustrate that trees and green spaces are often “unequally distributed among communities with varying demographics such as income and race” (Turner Scoff, 2019). When analyzing various texts, authors Jennings, et al., 2012; Landry and Chakraborty, 2009; Pincetl, 2010; and Schwarz et al., 2015 found a strong relationship between the percentage of urban tree cover and income: “the lower the income, the fewer the trees” (Balding and Williams, 2016) further highlighting the disparity in access to quality spatial environments.

10

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

Environmental movements such as tree planting, and the collective protection of trees (among other efforts) play an important role in responding to this gap, by encouraging communities to meet the following United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDG): Goal 3: “Ensure healthy lives and promote well being for all at all ages; Goal 13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts; Goal 15: Protect, restore, and promote sustainable uses of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt/reverse land degradation and habitat biodiversity loss, as further elaborated upon in Table 2 on the following page (Turner Scoff, 2019); additional data can be found in Appendix A. The following chapter explores the cultural significance in which trees play, and how including communities in the planting and preserving of trees can lead to a deeper connection between people and their natural environment.

11

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Human Habitats

12

Table 2. The benefit of urban trees and corresponding SDGs. Source: Turner Scoff, 2019

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

2.3. Cultural landscapes and Environmental Movements

Landscapes are dynamic, and constantly evolving with time as a direct result of natural and cultural forces, as well due to political and historical events. In addition, trees can unknowingly shape and influence our cultural experiences. As our physical and social environments evolve, certainly so do the transformations of rural areas into urban ones as the global population grows, resulting in the urbanization of smaller communes (Kaymar, 2013). According to Antrop (2005), “cultural landscapes are the result of the consecutive reorganization of the land to adapt its use and spatial structure better to change the societal demands”, which explains in simple terms the cause and effects of urbanization. Antrop (2005) further defines urbanization as “a complex process that transforms the rural or natural landscapes spatially, controlled by the physical conditions of the site and its accessibility by transportation routes” therefore encompassing terms such as urban sprawl, urban fringe, and suburbanization as effects of the urbanization process (Kaymar, 2013). In this context, importance and priority are made on society’s spatial planning needs, which manifest in different variations within the environment, and what society chooses to preserve or prioritize.

For example, in 1992 the Santa Fe Conference hosted by the World Heritage Committee was extended to ‘Cultural Landscapes of Outstanding Universal Value‘ (Antrop, 2005) which for the first time included parks, gardens, organically evolved landscapes such as relicts (traditional rural landscapes,) as well as associative landscapes, such as those with religious, artistic or spiritual values (Antrop, 2005); other examples of valued cultural landscapes include monuments, landmarks, and ecologically sound habitats. So how does a society choose what to preserve legally? Who gets a say in influencing these decisions, and how does politics influence whose cultural landscapes thrive, and whose are at risk to disappear? In other words, what we perceive as important, we value, therefore linking our perception of our environment to our cultural context (Antrop, 2005). These cultural landscapes help to define or contribute to shaping one’s identity concerning their environment, which acts as an emotional ‘landmark’ or genius loci that offer orientation in space, time, and historical context (Olwig, 2002). Understanding cultural landscapes in their immediate context can therefore lead to the preservation of and the implementation of certain environmental projects and infrastructures. This coherence leads to the transformation of cultural landscapes and identities, as a means for continuous adaptation for both the people and their environment (Antrop, 2005).

13

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Human Habitats

Kevin Lynch (1918 1984), a leading environmental theorist and urban planner of his time stated in his 1960 publication ’Image of the City:

“…We have the opportunity of forming our new city world into an imageable landscape: visible, coherent, and clear. It will require a new attitude on the part of the city dweller, and a physical reshaping of his domain into forms that intrigue the eye, which organize themselves from level to level in time and space and can stand as symbols for urban life. The present study yields some clues in this respect “(Lynch, 1960).

In this context, Lynch refers to the development and evolution of city form, which encompasses fundamental functions such as circulation, major land uses, and key focal points that further deepen a society’s connection with its built environment. In his work, Lynch also discusses how the visual environment is equally as integral as the spatial quality, to a community’s inhabitants as it pertains to their “imageability” or “a quality in a physical object which gives it a high probability of evoking a strong image in any given observer” which can also be linked to the visibility of a city through its spatial infrastructures (Lynch, 1990). The context of Lynch’s work is relevant when the image of the city is influenced by elements such as paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks as seen in figure 3, also known as transitionary or meeting points that shape the memories and cultural affiliation of a community. Lynch further discusses how orientation or disorientation plays a role in shaping our perception of our city, which is why we (as the public) must have a say in how our neighbourhoods evolve, change, and adapt with time. City perception as noted by Lynch is a key element in landscape architects continue to include in their standard practice.

14

Figure 3. Image of five physical elements and components Source: Jojic, 2018

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

Conclusion

The role of landscape architects (as well as arborists, urban foresters, and the like) in this context, becomes necessary to ensure a sustainable and qualitative outcome in building community capacity projects; especially when working with participatory and educational programs and projects (Elmedorf 2008). Furthermore, according to Elmendorf (2008), the degree to which community members can identify with, and enjoy nature through proximity to the space depends on the planning, maintenance, and use of trees in public landscapes. This is especially relevant when it comes to public landscapes and parks that have the potential to meet local people’s needs when they are involved in the planning, decision making, and building process. Other scholars such as McDonough et al. (1991) affirm that:

“Highly participatory environmental projects can promote social structure and organization, even in the most deteriorated neighbourhoods by building interaction and capacity through block clubs, neighbourhood organizations, church groups, and public and private partnerships.”

The more people are educated and involved in participatory environmental projects such as tree plantings, environmental restoration, or other environmental volunteer and educational based works, the more the quality of relationships among those involved, both local people and external organizations can increase through trust building, knowledge sharing, mutual aid, and community development (Rudel 1989; Lipkis and Lipkis 1990; Maslin et al. 1999). Case

studies have shown that inner city projects in which landscape architects, arborists, and urban foresters are closely involved help not only build community but also support the sustainable growth of healthy neighbourhoods and communities. Activities such as tree planting, have proven to be successful and repeatedly used by organizations such as the Philadelphia Green, TreesAtlanta, Friends of San Francisco Urban Forest, Los Angeles TreePeople, and the New York Green Guerrillas in support of peace building and reconciliation, especially within communities that fall victim to the effects of drugs, crime, violence, and despair (Elmendorg, 2008).

Tree planting encourages and enables individuals of said community to have an “immediate, tangible, and positive effect on their environment, thereby fostering community pride and opening channels for individuals to meet their neighbours and tackle community problems as a collective (Kollin 1987). These initiatives offer an alternative approach to conflict resolution through environmental and ecologically sound principles, and an opportunity to reformulate new collective values as a basis for sustainable community development and capacity building.

Nevertheless, it is necessary that the local community is equally as involved in these projects

15 2.4.

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Human Habitats

as is the municipality, to ensure equitable involvement and representation from all relevant stakeholders.

Through such movements, and with the support of professionals such as landscape architects, arborists, and urban foresters, there is an opportunity for environmental restoration that no doubt has an impact on the economic, social, and environmental elements of any given community, including vulnerable populations such as the ex combatants in Colombia. Additionally, the role of trees in developing sustainable human habitats aids in the inclusivity of different stakeholders and ecological drivers but why stop at trees? Through participatory and collaborative approaches such as those listed in the above literature review, communities, such as that of Tierra Grata have an opportunity to further push for spatial elements such as bike paths, well maintained streetscapes, and improvement of public transportation, among other spatial interventions (Elmendorg, 2008) which are especially important in planning for new settlement or renovating disenfranchised communities. To conclude in the words of Shrieber and Vallery (1987):

“Planning and completing tree planting, urban gardening, and other types of green projects inspire neighbourhood and community groups to change the environment of their streets giving a new understanding of and character to their neighbourhood and the city as a whole.”

16

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

3. URBAN AGRICULTURE: A REVIEW OF SELECTED CASE STUDIES

This chapter examines the emergence of urban agriculture (UA) in the Global North and Global South. The chapter identifies the role, potential, and challenges of UA, as well as its various typologies Through an analysis of the existing literature, the discourse of food justice politics and food urbanism, is discussed, to link the concepts of landscape architecture, urban agriculture, and food centered cities.

3.1. The Global Role of Urban Agriculture

“Urban agriculture is associated with urban land squatting and is viewed as a socio economic problem, not a solution. As a result, authorities are hesitant to be more proactive on urban agriculture because it is largely seen as resulting from a failure to address rural development needs adequately.”

Mayor Fisho P. Mwale, Lusaka, Zambia (Mougeot, 2006)

To most people, urban agriculture (UA) is swept under the rug and simplified as the concept of urban gardening in a developed city; but the role of UA goes beyond that. UA manifests itself in various forms and typologies, especially in developing peri urban towns and landscapes. But what exactly is UA? Urban agriculture can be defined as the growing of plants and livestock within a city (intra urban) or the areas surrounding the towns (peri urban agriculture) (Chatterjee et al., 2020). It can also be understood as the processing of raw materials into commercial activities such as city farming, edible urban landscape, and community vegetable and fruit gardens, among other examples. (Chatterjee et al., 2020). The official definition adopted by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) refers to UA as “an activity located within or on the fringe of an urban area, which cultivates, processes, and distributes [food] products, and supplies resources mainly to urban areas (Lebedeva, 2008). Urban agriculture, by extension, encompasses the principles of landscape architecture, although it focuses on one theme in particular: food security.

Urban and peri urban agriculture (UPUA) becomes increasingly prevalent in the discourse of city planning as it overlaps with the topics of urbanization, sprawl, and food security. The correlation between the two is that as cities plan for growth, incorporating urban and peri urban agriculture becomes a necessity in urban planning and land development conversations. In this case, urban planners and landscape architects must work with the local community and governing municipality to shape the way policies are made. Cities are designed to ensure equitable opportunities such as access to land tenure while simultaneously offering food sovereignty to the communities involved. For example, it is estimated that by 2030, approximately two thirds of the world’s population will live in cities (Azunre et al., 2019). The

17

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Human Habitats

implications of this will be reflected in the supply and demand of urban lands, which are often allocated through adequate land tenure and ownership, either bought or inherited (Azunre et al., 2019). Important questions arise, that we must answer, especially in the context of avoiding conflicts and ensuring peace in our communities. For example, what happens to those who find themselves on the peri urban scope of the city with no land to their name? What opportunities would they have to participate in securing their means for food security and overall livelihood?

When it comes to an understanding of how urban agriculture manifests in various contexts, some perceive it simply as gardens and farms within the inner city (Cohen et al. 2012), while others include agricultural activities such as those performed in peri urban landscapes (Opitz et al., 2016). Meanwhile, the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) defines it as “any products in the home or plots in an urban area” (FAO, 2003). There are numerous definitions of what is considered UA. Regardless, the role of urban agriculture remains a topic of discussion, especially within the context of global food security and urban food systems planning (Opitz et al., 2016). The differentiation between urban and peri urban landscapes can be defined based on how it is perceived by the Global North versus the Global South; “the core concept of both definitions being that UA involves food production in urban areas” (Opitz et al., 2016). The juxtaposition of the word “agriculture” in UA implies the general understanding of forms of farming and gardening, usually in rural areas. Therefore, the introduction of peri urban agriculture (PUA) offers a means of categorizing transitory spaces. Peri urban agriculture is traditionally understood as a “residual form of agriculture at the fringes of growing cities” (Opitz et al., 2016). Although scholars have not yet officially determined the spatial definition of such spaces, some authors indicate that “peri urban agricultural activities take place within a buffer of 10 to 20 km of the urban geographic boundary” (Thebo et al., 2014). These zones are mostly found within the transition of rural to urban zones, which means they benefit from lower population densities, yet lack adequate infrastructures compared to cities (Opitz et al., 2016).

18

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

3.1.1. The Global North

As the current trends in rural to urban migration continue, countries around the world have debated the role of urban agriculture as a response to feeding the growing population. Although the concept of UA has recently become a ‘buzzword’ and topic of debate among researchers and farmers, it holds weight in history. It has been informally recognized since the Byzantine Empire incorporated its framework to address food security, particularly against sudden interruptions in food supply lines (Koscica, 2014). Land and food supply shortages have always generated a more intensive means of production. Due to urbanization, cities have begun searching for a self sufficient way to feed themselves, such as the case in Figure 4, illustrating an aerial photo of a circular “community of communities” designed by landscape architect Erik Mygind in 1964. In this community known as Brøndby Haveby the design mimics “the traditional patterns of the 18th century Danish villages, where people would use the middle as a focal point for hanging out, mingling, and social interchange between neighbours” says photographer Henry Do (Marshall, 2020). Settlement patterns are directly affected by urbanization, especially within the urban realm, which is why it is no surprise that organized agriculture is becoming more prevalent once again. In the following pages, urban agricultural trends in some major countries of the Global North are highlighted.

19

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Human Habitats

I. England

The origin of organized agriculture within the public realm led to the ‘Garden City Movement,’ a 20th Century urban planning movement that emerged in the UK and was first introduced by Ebenezer Howard in his book Garden Cities of Tomorrow in 1902 (see Figure 5) (EPRS 2017).

This movement offered an alternative to living in densely populated urban areas, depicting what a “garden city” could offer: a combination of country and city living surrounded by greenbelts. In other words: the answer to feeding a growing population. Howard organized the Garden City Association in 1899, where two garden cities were built: Letchworth Garden City and Welwyn Garden City, both in Hertfordshire, England, UK (EPRS 2017). Soon enough, the garden city idea became influential in other countries, such as France, Germany, Finland, Ireland, Poland, Canada, and the US (EPRS 2017).

20

Figure 5: Garden City Map by Ebenezer Howard. Via Wikimedia Commons, public domain, 1902

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

II. United States and Canada

In the past century, cities in North America have been able to recognize the phenomena of urban agriculture and initially promoted “household and community gardening for food security in times of economic crisis, such as the British Allotment Act of 1925 and the War Gardens of Canada, 1924 1947” (Koscica, 2014). During this time, North Americans depended on gardening as a livelihood, primarily through the Great Depression of the 1930s (Mok et al., 2013). During this time, the National Victory Garden Program, supported by the War Food Administration, ran propaganda (as seen in Figure 6) to promote the means of gardening as a form of patriotism and civic responsibility (Mok et al., 2013). This illustrates the early appearance of land and food sovereignty. As a result of these gardens, the demand for commercial food supplies decreased, aiding food security, especially during severe shortages (Mok et al., 2013).

21

Figure 6. Victory Garden posters from World War II. Office of War Information, National Archives (left) and Morley, War Food Administration (right) / Public Domain

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Human Habitats

III. Australia

Other countries, such as Australia, adopted urban agriculture in a similar trend to that of the US and the UK, as wartime and post wartime practice. During the 1930s, as Australia was also amid a deep economic recession, the introduction of backyard “home gardens” and small scale poultry farms became popular, with up to 70% of people growing their food (Mok et al., 2013). Informal campaigns began to appear around 1941 to encourage wartime food growth, and in 1943 an official Grow Your Food campaign was launched by the Commonwealth Department of Commerce and Agriculture of Australia (Mok et al., 2013). A study by the University of Melbourne found that 48% of the sampled households produced food. However, home food production was neither a practical nor accessible option for the poor. This highlights an essential disparity in the topic of urban agriculture and accessibility (Mok et al., 2013). In any case, Australia’s first community garden was established in Melbourne in 1977, before the permaculture movement surged only a year later. The book, Permaculture: A Perennial Agricultural System for Human Settlements by Bill Mollison and David Holmgren was published in 1978, promoting an “alternative agricultural system in which plants, animals, and humans were integrated into the ecosystem and supported each other’s functionality.” (Mollison and Holmgren, 1978). As a result, permaculture became an instrumental step in the movement of contemporary urban agriculture, and its principles became the foundation for a campaign in social and environmental philosophy about sustainable human habitats, as seen in Figure 7 on the following page. (Mok et al., 2013) The above is a summary of the emergence and trends of the urban agriculture movement as it manifested in various forms in the Global North. To date, spaces such as rooftops, balconies, vacant lots, and communal areas have become the most suitable option for agricultural purposes within cities in the Global North. In contrast, undeveloped lands, marginal lands, and community plots have been used for food for household consumption in the Global South, as their relationship and dependency on food production systems vary (Azunre et al., 2019).

22

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

23

Figure 7. Permaculture principles according to Bill Mollison. Source: The Seedling at Sagada, Australia

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Human Habitats

3.1.2. The Global South

Research indicates that approximately “800 million people around the world actively engage in the practice of urban agriculture”, which accounts for an average of 15 to 20 percent of the world’s food production (Koscica, 2014). It is evident how urban agriculture can play an essential role in the livelihoods of households, particularly those with low income. In this way, it is not only a commercial tool for the casual growing of food but has started to become quite an essential and renewable resource in the quest to find autonomous food systems. For example, a 2011 World Bank and Resource Centers on Urban Agriculture and Food Security (RUAF) Foundation, and a comparative study in Accra, Lima, Bangalore, and Nairobi, concluded that 30% of urban producers consider urban agriculture an essential source of income (Koscica, 2014). Research also shows that “households that engage in [urban] agriculture may have access to comparatively cheaper food and a wider variety of particularly nutritious foods” (Koscica, 2014).

However, the concept of urban agriculture was not always seen positively by local authorities. In the peri urban areas of Nairobi in Kenya and many other African cities, agriculture was discouraged and, for a long time, even forbidden to prevent criminality and “disorder” (Ayaga et al., 2005). On the opposite side, there are many countries where governments promote the development of urban agricultural production. Latin America, Argentina, Brazil, and Cuba have developed national policies and programs promoting urban horticulture (Veenhuizen, 2006). In the Global South, the practice of urban agriculture has manifested itself as a means of survival and livelihood. Therefore, the demand in practice also becomes a cause for concern when the needs of the most vulnerable cannot be met. Trends in major cities of some select countries in the Global South are reviewed in the following sections.

24

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

I. Nairobi, Kenya

Kenyan activist, and Nobel Peace Prize winner, Professor Wangari Maathai, eloquently pieces together the link between decolonization, the importance of Indigenous land sovereignty, and thriving urban agriculture in her 2006 memoir, “Unbowed.” She explores how urban agriculturalists and academics tend to overlook the needs and opinions of the locals while attempting to develop the land. The chapter “Foresters Without Diplomas” mainly details the genesis of Kenya’s Green Belt Movement founded by Professor Maathai. In essence, this Movement is a tree planting initiative whose aim is to provide Kenyan women with a source of food and employment (Maathai, 2006). Simultaneously, the Green Belt Movement “would offer shade for humans and animals, protect watersheds, bind the soil, heal the land by bringing back birds and small animals and regenerate the earth's vitality” (Maathai, 2006). Maathai believes that “the movement has shown that sustainable development can be linked to democratic values such as promoting human rights, social justice and equity, including the balance of power between men and women” (Maathai, 1985). This belief is also evident in various examples of landscape architecture and urban agriculture practices in the Global South. Through this movement, she was able to assist women as seen in Figures 8 and 9 in planting over 20 million trees on schools, farms, and other private compounds, starting in Kenya and spreading further into East Africa (Maathai, 1985). This illustrates how women and children can be empowered to create their source of livelihood and eventually, financial independence.

Nevertheless, food insecurity is a significant problem throughout Kenya, like in many other African countries. According to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics report and the University of Nairobi African Women’s Studies Center, “14.5% of Nairobians suffer from low food security; meanwhile, 11.7% are chronically food insecure” (University of Nairobi, 2014).

Since 2015, the Government of Kenya has initiated the Urban Agricultural Promotion and Regulation Act, which establishes a regulatory framework under which urban agriculture in Nairobi may be practiced and overseen in compliance with the law (New York Food Policy, 2018); meaning that legally, urban agriculture now has the potential to provide healthy food to the city’s most vulnerable populations. According to this act, “urban agriculture” involves the cultivation of crops, breeding and keeping livestock, and using land for gardens, nurseries, and agroforestry (New York Food Policy, 2018).

25

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Human Habitats

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Human Habitats

26

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

Additionally, the government has pledged to undertake various programs which promote urban agriculture, such as the training and capacity building of farmers in sustainable crop cultivation, the promotion of aquaculture, and ensuring the collaboration between relevant stakeholders to manage organic waste among other initiatives (New York Food Policy, 2018) This demonstrates the room for evolution and support from local authorities to ensure the success of such urban agriculture. Figure 10 illustrates the Wangari Maathai Institute Master plan, a 50 acre green campus on the University of Nairobi Kabete campus. The WMI is envisaged as a functional and inspiring hub of activities in natural resource management and education for sustainable development, showing the potential a community has when the government offers support (WMI Institute, 2022).

27

Figure 10. WMI Landscape Master plan. Source: Wangari Maathai Institute for Peace & Environmental Studies (WMI)

II. Dakar, Senegal

Figure 11. An urban agricultural farmer in Niayes Valley, Senegal. Source: Madeleine Bair

Like many other places worldwide, Dakar, Senegal is not immune to food insecurity and limited public access to growing spaces (Halliday et al., 2019). Fortunately, certain solutions to solve this issue have been explored. Dakar’s micro garden program is an example of such a solution, as illustrated in Figure 11. Introduced in 1999 by the Senegalese Government and the FAO, this program provides an opportunity for locals to learn the skills needed to grow their soil less gardens. In turn, families and individuals reap the benefit of having direct access to fresh, nutritious fruits and vegetables (Cather, 2016). The FAO (2018) defines micro gardening as the intensive cultivation of a wide range of vegetables, roots, and tubers, and herbs in small spaces, such as balconies, patios, and rooftops”; and in the case of Dakar, this simple yet complex idea has improved the food supply and security of vulnerable populations located in urban and peri urban areas (Cather, 2016).

This program initiated in Dakar, Senegal can ultimately be considered an eco feminist initiative for two main reasons. Firstly, locally sourced materials such as peanut shells, rice straw, coconut fiber, and sand, are repurposed and used as growing substrates (Halliday et al., 2019). Old wooden pallets and car tires are also repurposed as planters (Cather, 2016).

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Human Habitats

28

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

These are items that would otherwise be considered garbage. The program also “integrates horticulture production techniques with environmentally friendly technologies suited to cities, such as rainwater harvesting and household waste management” (Cather, 2016) “Secondly, the program “[improves] food security without stigmatization” (Cather, 2016), because micro gardening was adopted by all demographics including but not limited to: those living in poverty, the upper class, all gender identities, disabled individuals, incarcerated people, youth and elders (Cather, 2016; Halliday, 2019). Through micro gardening, the citizens of Dakar are empowered to continue having agency and autonomy regarding food security. For example, matriarchs, divorcees, and widowed women can diversify their income and remain independent by cultivating their micro gardens (Cather, 2016). The act of being able to grow their food and sell the surplus also assists in poverty reduction (Cather, 2016). Overall, Dakar’s micro garden program has been incredibly successful; over 4000 families have participated in this program, and each participating family “consumed between 5 and 9 kg of vegetables per month, on average more than double that consumed by families not participating in the program” (Sarr, 2019. As seen in Figure 12, this has become a widely practiced initiative.

29

Figure 12. Micro gardening training centres in Dakar, Senegal. Source: Ms. Ndeye Ndack Pouye Mbodj.

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Human Habitats

III. Bogota, Colombia

In Colombia, informal settlements make up essential parts of the cities, as these areas possess strong links to agricultural practices, especially among rural migrants (Hernández García and Caquimbo Salazar, 2017). The presence of urban agriculture in Bogota has been recognized both from the residents’ and governments’ points of view: for the residents, it is seen as a rural tradition, and for the government “as a way to contribute nutrition to low income populations located in these [rural] areas” (Hernández García and Caquimbo Salazar, 2017). Since the 1960s, there has been a shift in migration from rural to urban areas which has increased the densification of settlement patterns (as seen in Figure 13 on page 33). As a result, the government has an opportunity and a responsibility to respond to this growth through the process of local food production and urban farming (Hernández García and Caquimbo Salazar, 2017).

According to Bogota’s development plan (2015), urban and peri urban agriculture (UPUA) is defined as “a model of food production which allows neighbourhood communities to organize and implement agricultural systems, through practices that optimize resources, waste management, and do not interfere with the ecosystems, while using a range of technologies” (Bogota, 2015). Additionally, in Bogota, the open spaces in informal settlements play a role in shaping both the physical environment and social dynamic of the inhabitants, primarily because the spaces are occupied by the locals, which often indicates their struggle and successes (Hernández García and Caquimbo Salazar, 2017). For example, open spaces can become social places known as barrio, meaning they are “places for cultural exchange and building values” (Hernández García and Caquimbo Salazar, 2017) which also include food growing initiatives, as well as entertainment facilities such as playgrounds and green spaces. In the city, these spaces are also where urban agriculture eventually manifests as a means for household horticulture among low income people, especially women. (Hernández García and Caquimbo Salazar, 2017). To them, cultivation isn’t simply about agricultural activity but a way to incorporate the landscape as a symbolic value and occupy territory, especially for displaced people (Hernández García and Caquimbo Salazar, 2017). In addition, access to these spaces allows them to utilize their knowledge and re establish a bond with their new habitat to familiarize them with their new land. However, the challenge with these spaces can often mean a lack of space, poor soil quality, and poor water access. (FAO, 2014).

30

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

The discourse about urban agriculture in Bogota is rooted in its grassroots organizations, especially those of different social clusters, i.e., Red de Agricultura Urbana de Bogota (UA network of Bogota) (Hernández García and Caquimbo Salazar, 2017). The main goal of this organization is to establish a platform to exchange and discuss ideas (knowledge sharing) related to urban agriculture to improve and promote the collaborative practice. Another example is the Arte Productivo (Productive Art) initiative, a community garden strategically designed within an informally developed area known as Rafael Uribe Uribe (Hernández García and Caquimbo Salazar, 2017). Through a training agreement with the city and Uniminuto University, the participants were educated on growing plants for elevated, colder climates. As a result of this process, over 700 people of working age were trained within the first four years (Hernández García and Caquimbo Salazar, 2017). This is a prime example of what can occur when urban agriculture is legitimized with the help of the local government by investing knowledge within a vulnerable community. Valuable skills are offered to improve the population’s livelihood and enrich their physical environment, not only aesthetically but also by including indigenous plants. In addition, locals cultivated medicinal and ornamental plants within these gardens, offering a means of self consumption rather than a means to survive financially.

Another example of urban agriculture, or in this case, agroecology in Bogota is known as Sembrando Confianza, which is a program of Fundacion Proyectar Sin Fronteras (PSF), a non profit organization founded in 2007 (Sembrando Confianza, 2021). Since 2012, the goal of Sembrando Confianza has been to promote agro ecological practices and environmental education in vulnerable territories in urban, peri urban, and rural areas in Colombia. This is an excellent example to illustrate the overlap in environmental sectors; agroecology seeks to promote “the sustainability and justice of food systems, as it boosts the ecological processes of nature to improve productivity and avoid future agricultural problems” (Sembrando Confianza, 2021). PSF utilizes the principles of agroecology to consider not only the technical aspects, but also to encompass the socio economic, political, and environmental aspects of the practice, which can sometimes be unintentionally neglected or left unaddressed (Sembrando Confianza, 2021). It is based on the concept of social economy, which according to the organization “promotes cooperative work and sustainable development, placing special emphasis on the person and the social object over the capital.” (Sembrando Confianza, 2021).

31

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Human Habitats

A final case of urban agriculture in practice can be found in the informal settlement of Bosa, in partnership with the Indigenous association of San Bernardino (Hernández García and Caquimbo Salazar, 2017). This Indigenous community started developing urban agriculture in empty plots initially set out for future social housing projects; however since not everyone had access to this land, they began to use their roofs and balconies for cultivation (Hernández García and Caquimbo Salazar, 2017). These examples and initiatives reflect the range of urban agriculture in various scales and contexts, especially as an activity for marginalized groups to be empowered and independent with or without external support. After urban agriculture was officially recognized in 2004, Mayor Luis Eduardo Garzon implemented the policy ‘Bogota sin Hambra (Bogota Hunger Free) (Hernández García and Caquimbo Salazar, 2017). The goal of this policy was to implement the project Urban Agriculture: Environmental Sustainability without indifference for Bogota (Hernández García and Caquimbo Salazar, 2017) which was and continues to be led by Bogota’s Botanical Garden. Additionally, a master plan for Bogota's food supply and security was implemented through law in 2006, using the plan as a basis for urban design and food supply regulation, highlighting the potential of food production through urban farming. Today, the Bogota Botanical Garden continues to promote urban agricultural initiatives in response to climate change adaptation, access to healthy food, implementation of agro ecological practices, and incorporation of urban and rural sustainable farming (Hernández García and Caquimbo Salazar, 2017).

The challenge and criticism for Bogota, despite all these initiatives, is that a class divide still exists, meaning the demographic that truly has access to these opportunities is, in fact, limited. Therefore, a public policy still needs to challenge the city’s urban design to meet the ideal social and environmental conditions necessary for urban agriculture for all classes (Hernández García and Caquimbo Salazar, 2017). The trends in the usage of urban agriculture highlight it as a tool for addressing food insecurity and improving the overall livelihood of its users as an adaptive strategy. Although the practice of growing food in developing cities differs, there exist certain principles and similarities in implementation that remain the same. Regardless, city governments are often faced with two certainties: first, people will continue moving to cities and search for self sustainable ways to grow and access food; secondly, with adequate support and policies from city governments that encourage UA, the population of urban farmers will not only increase but thrive (Mougeot, 2006).

32

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

Marie Tina Asoh Ajesam

33

Figure 13. View from TransMi Cable Car facing the top of Ciudad Bolívar. Source: Marie Tina Asoh

The Role of Landscape Architecture in Developing Human Habitats

3.2. The Politics of Food Justice in Colombia