1 minute read

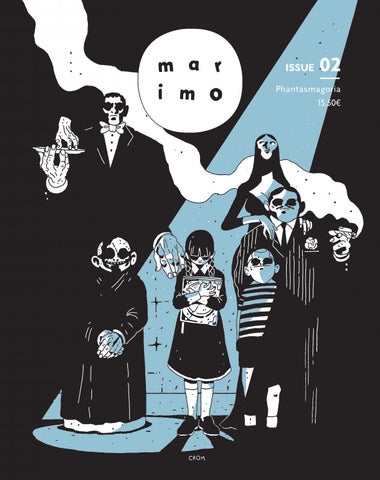

Robertson's Phantasmagoria

Imagine walking into Pavillon de l’Échequier in Paris one spring evening and sitting with several friends, hoping to experience a new theatrical event. As the candles are extinguished plunging the hall into darkness, the spectral drama unfolds. Smoke creeps across the room and people rush forward to the host asking to see phantoms of the past. Spectres hover above, winking in and out of existence, and people begin to flee the theatre in terror. Whispers or claps of thunder causes others to draw swords, or cry in panic. The host, Étienne-Gaspard Robert, or better known as “Robertson”, through his Fantoscope, conjures image after ghostly image, moving them closer to the petrified audience, keeping his promise and bringing the dead back to life. This is Phantasmagoria. In 1797 F

rance, as Robertson began his Phantasmagoria, there was a heavy interest in the macabre following the Reign of Terror (1792-1794). If executions weren’t enough, the public could now witness what they thought happened after life. Robertson had a similar dark interest since childhood and because he was a scientist, his equal interest in optics led him to early magic lantern shows. Following these, he developed many of his own techniques to make a new type of event: an immersive, horror spectacle. But also to help it stands out from the eventual copycats that emerged as his secrets were revealed.

His Fantoscope was on wheels, so it could move forward or back, to create the illusion of the spirits growing larger. Also, the aperture could be adjusted to allow more light through the magic lantern, which made the ghost glow with more intensity as it rapidly approached. Robertson’s adjustment to the magic lantern also allowed him to use multiple slides in a single projector, which could create a crude semblance of movement. A face was given brighter eyes, and then that slide could be removed to create the illusion of life in the phantom.

Phantasmagoria is central in the history of imagination. A mixture of dark, smoky, moving imagery as spectres crept in and out of existence around the audience, mixed with the eerie voices projected by a ventriloquist and accompanied by the unsettling tones of a glass harmonica; you can imagine the chilling effect it could still have today. Thankfully, through his Mémoires, he left detailed instructions on how each effect was created. This is close to 80 years before Eadweard Muybridge began his pioneering work on animal locomotion. Robertson’s adaptations on the magic lantern marked an important step toward the idea of successive images being played over each other, creating movement in order to animate, which of course means, to “bring to life”.