2 minute read

A Alchemy

Alchemy

It might seem unusual that in a College renowned for scientific excellence, room should be found for books extolling the practice of alchemy, the arcane belief that base matter can be transmuted into gold.

But just as astronomy grew out of astrological speculation, so modern chemistry stemmed from alchemy. As a hermetic philosophy, alchemy offered its disciples both a material path in pursuit of gold, and a spiritual quest for the Philosopher’s Stone, the key to understanding the secret workings of the universe and the mind of God. The falling away of such mystical aims from laboratory practice towards the end of the 17th century was one indication of the onset of the Age of Enlightenment.

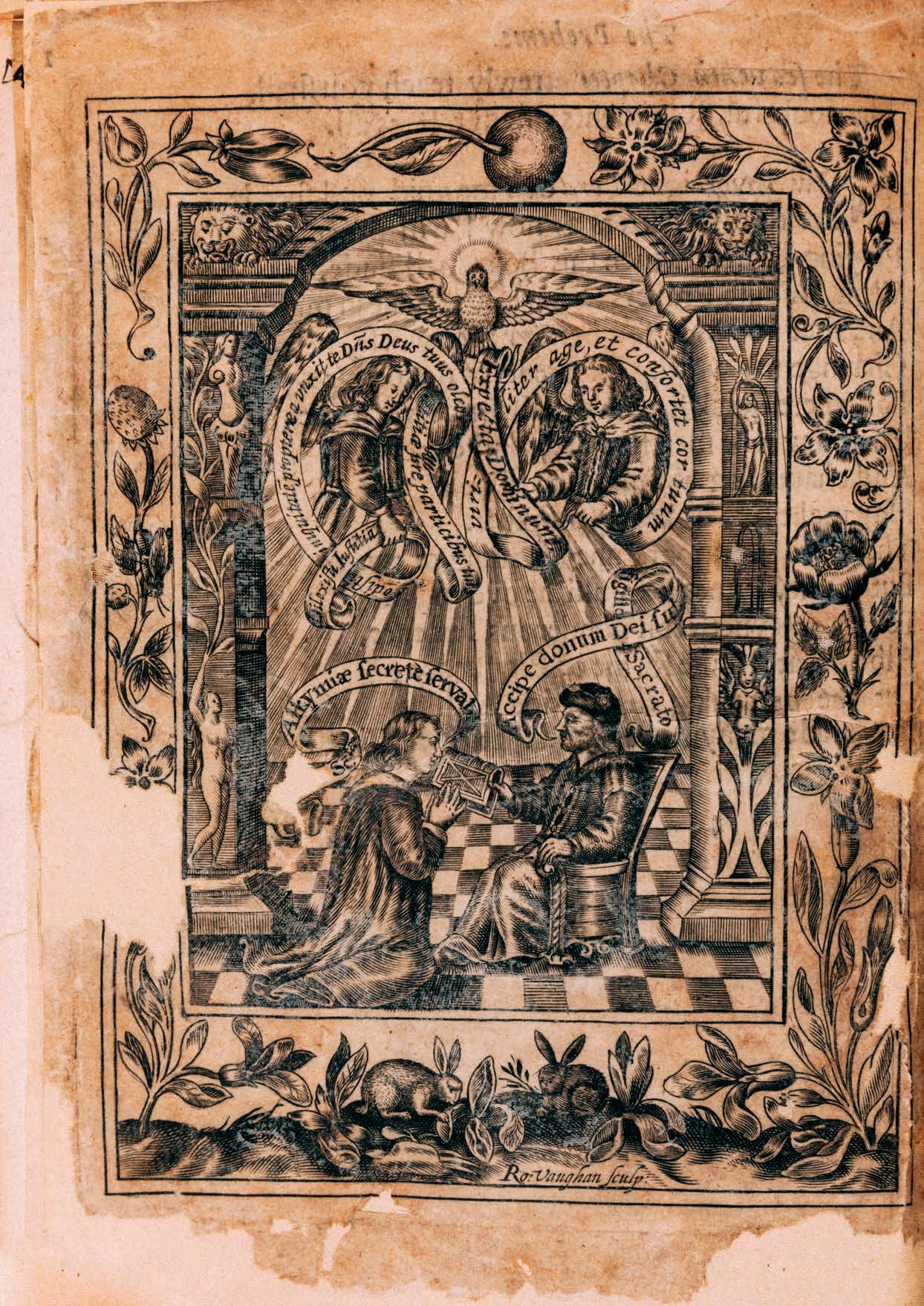

The College’s earliest alchemical book, Philipp Ulstad’s Coelum philosophorum seu de secretis naturae, was published in Strasbourg in 1528. It is richly illustrated with extraordinary woodcuts of apparatus such as kilns, crucibles, retorts, flasks and alembics set up to distil the hermetic quintessence. The book’s title page shows a concave mirror concentrating the rays of the sun in order to heat the contents of an alchemical flask. Ulstad, a physician practising in Freiburg, was particularly interested in alchemy’s potential to distil effective medicines. More abstruse in his interests was Elias Ashmole (1617–1692), founder of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, and an adept in alchemy and magic. The College owns two works by Ashmole, the first his Theatrum chemicum Britannicum from 1652, an anthology of English poetical texts, mostly from the Middle Ages, which Ashmole believed carried occult allusions to alchemical secrets. In one image we see Ashmole kneeling before an alchemist who gives him a book with the words ‘Receive the gift of God under the sacred seals’. Some pages of the College’s copy show considerable damage from burns and chemical corrosion, suggesting that the book was used in earnest in an alchemist’s workshop. Interestingly, despite dating from the mid-17th century, the copperengraved illustrations follow the visual conventions of medieval illuminated manuscripts, a reminder that alchemists often appealed to historical authority for their recipes and formulations. In Ashmole’s second book, Fasciculus chemicus from 1650, the author, in keeping with alchemical secrecy, adopts the anagrammatic disguise ‘James Hassole’ – the letters ‘I’ and ‘J’ being interchangeable in the 17th century.