GCMF

We hope you enjoy this special excerpt from the Summer 2024 issue of “Marshall” magazine.

We hope you enjoy this special excerpt from the Summer 2024 issue of “Marshall” magazine.

e bivouacked in a pretty little apple orchard a short distance from the beach. I got to use my high school French with the couple who owned the orchard and their young son.”

That is the extent of the information my father, Richard H. Hobbs, shared with his children about his experiences during and after D-Day in Normandy, France. Like many who served in World War II, he simply didn’t want

to talk about the difficult times, only the short, pleasant moments, such as an apple orchard.

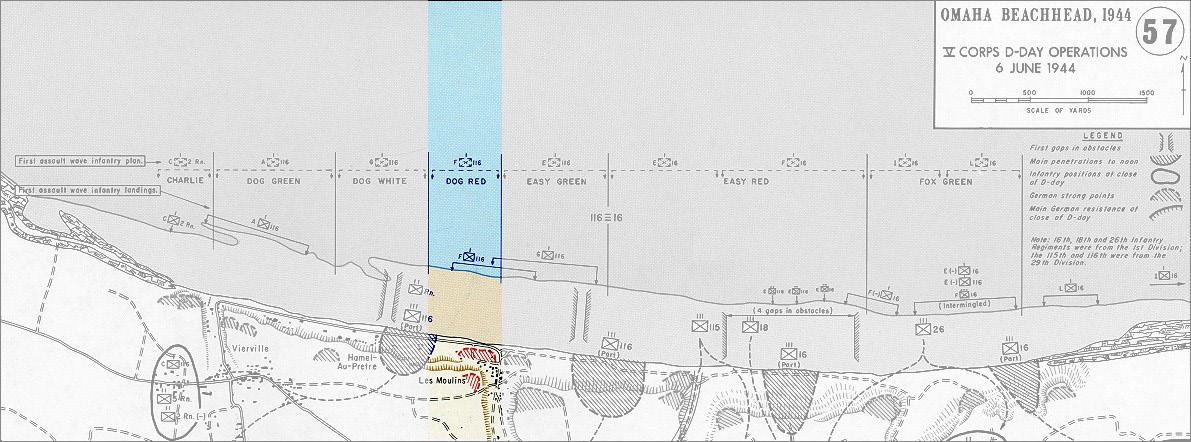

When I began working at the George C. Marshall Foundation in 2019, one of the first archival items I came to know was the corps-level D-Day map of OMAHA Beach— the last of its kind—that was carried by Gen. Leonard T. Gerow, commander of the beach on June 6, 1944. I wanted to better understand the markings on the map, and my research led

Staff Sgt. Richard H. Hobbs in a portrait taken in Gloucester, England, in 1943, and sent to his widowed father and aunt. Hobbs family photo.

Left:

U.S. soldiers march toward the Torquay Harbor, Devon, England. Torquay Museum photo.

Center:

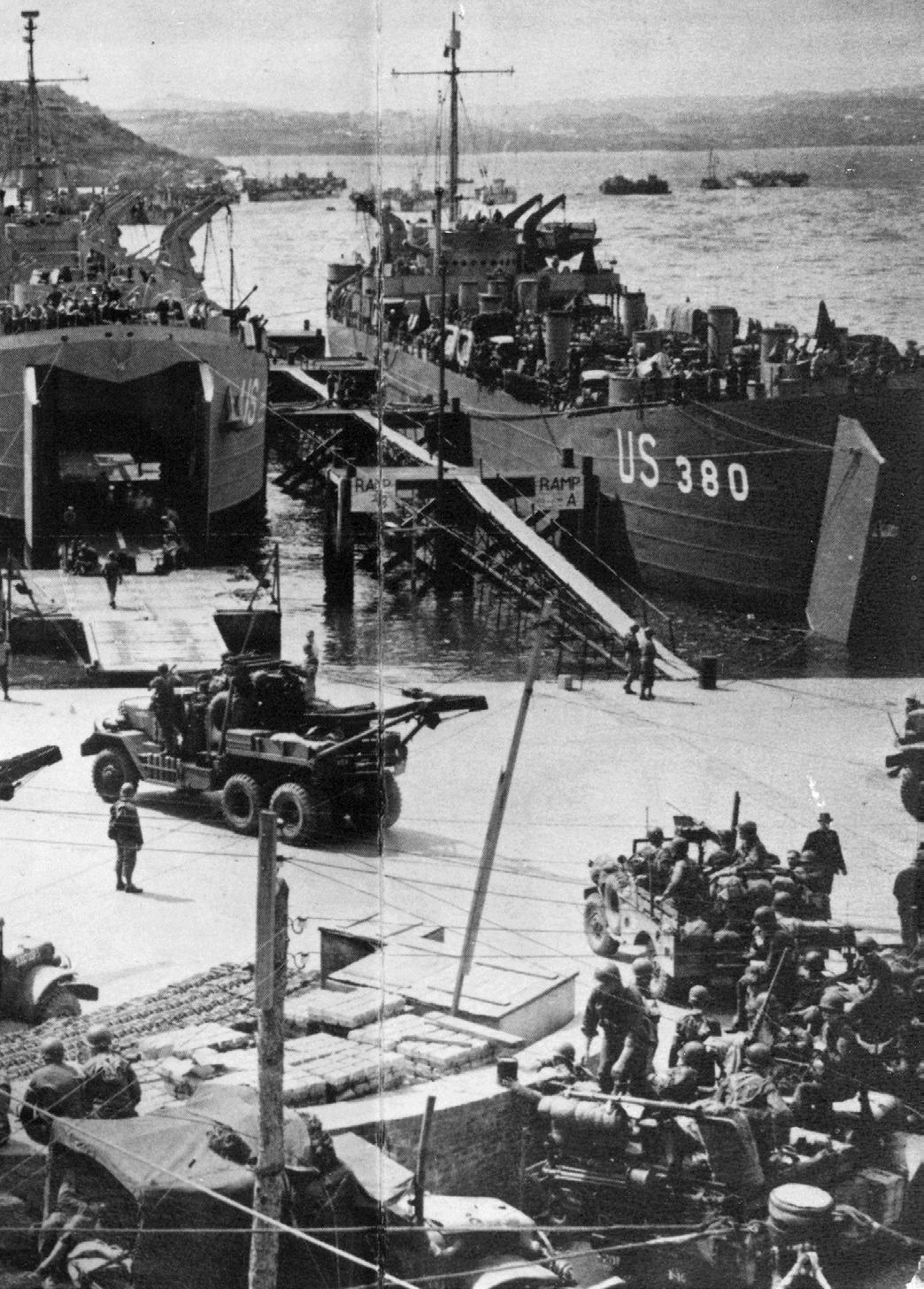

U.S. military vehicles loading at Brixham Harbor. Torquay Museum photo.

Right: Landing Ship, tank with 2.5-ton trucks loaded on the deck heads across the English Channel toward France. U.S. Navy photo

me to some facts about my father’s experience as a sergeant on OMAHA Beach during the invasion of Europe. I learned from the U.S. Army in World War II series that he was part of a truck company that landed on OMAHA Beach on D-Day. This amazing piece of the D-Day puzzle left me wanting to know more about how my father prepared for and participated in Operation OVERLORD. I poured over books, maps, and documents (most of them digitized) looking for the information my father didn’t share.

Richard Hobbs enlisted in the District of Columbia National Guard, part of the 29th Infantry Division, in 1940, and was trained to be a military policeman in the 29th Military Police Company. When the 29th was federalized by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 3, 1941, with Maj. Gen. Milton Reckord as its commander, Private Hobbs was enlisted into the Quartermaster Corps and sent to Fort Meade, Maryland, as a truck driver. The GMC 2.5 ton, 6x6 truck he was assigned was a bit

different from the Model A Ford on which he had learned to drive.

The 29th participated in the large First Army maneuvers in North and South Carolina in October and November 1941. On the return to Fort Meade, portions of the unit encamped at the old Civilian Conservation Corps land that later became Camp Pickett (now Fort Barfoot), Virginia, on Saturday, December 6, where they heard about the attack on Pearl Harbor the next day. Training continued throughout the spring and summer of 1942 at Fort A.P. Hill (now Fort Walker), Virginia, and Camp Blanding, Florida. Private Hobbs carried soldiers and equipment for this training, driving many miles and long days.

Maj. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow took command of the unit just a few days before Corp. Hobbs boarded the Queen Mary for the trip to England. He was based in Gloucester, in southern England; although he spent a lot of time carrying men, and hauling equipment and supplies throughout England during the

next 18 months. My father said that many roads were lined by stone walls and hedgerows, and were too narrow for the big trucks, but they had to make it work. He thought there was probably some ruined landscaping after the big 6x6 vehicles rumbled through.

In February 1944, Sgt. Hobbs, now in the 3704th Quartermaster Truck Company, part of the 6th Engineer Special Brigade, participated in amphibious training at Goodrington Sands, Devon, as the truck company had no

previous training in amphibious landings.

In May, Sgt. Hobbs and his truck were stationed in Torquay, on the Devon Coast, in preparation for the invasion. By June 3, he had driven his truck, with a .50 caliber machine gun mounted on top, onto the deck of an LST (landing ship, tank) with other trucks, equipment, and soldiers in preparation for the journey across the English Channel. The weather was good June 4, but horrible June 5 with rain and wind. My father said the Channel

Map showing the Dog Red section of OMAHA Beach. Wikimedia Commons graphic.

Crane at a supply dump in Normandy removing a sling load of supplies from a 2.5-ton truck. GCMF photo.

was very rough, and many of the soldiers were seasick. He was grateful not to be susceptible to seasickness. The 6th Engineer Special Brigade was scheduled to support the Charlie, Dog White, Dog Red, and Easy Green sections of OMAHA Beach, in support of the 116th Regimental Combat Team companies, including Company A, also known as the “Bedford Boys.”

Before dawn on June 6, Sgt. Hobbs likely drove his truck onto Rhino ferry 1221 headed for OMAHA Beach. The large craft was loaded with 39 vehicles and 94 men. They could hear the naval bombardment and knew the invasion had begun, but the fog was so bad the soldiers couldn’t see the beach, even in day-

light. Several hours after the invasion began, the Seabee crew started the outboard motors on the Rhino and motored as close to the shore as possible. Sgt. Hobbs drove his truck down the ramp, into the surf, and chugged onto the shore of the Dog Red section of OMAHA Beach, near St.-Laurent-sur-Mer, France.

I recently learned from my mother that during a very dark time for him in 1964—the twentieth anniversary of D-Day—my father spoke to her about driving onto OMAHA Beach on June 6. He said that a lane had been cleared of obstacles, land mines, and casualties to allow the trucks to traverse the beach. Around him was the chaos of a battle not yet ended; medics tending to wounded soldiers, artillery

and small arms fire, broken equipment, and the bodies of soldiers lying where they fell. My father broke down speaking to her about the injured and dead; men that he had known and worked with since 1940. My mother told me that he never again spoke of D-Day.

The trucks of the 3704th were loaded with ammunition, rations, and engineer equipment. At first, supplies piled up on the beach faster than the few trucks ashore could move them inland to the initial supply dumps. Transfer points were established on the beach to enable DUKWs (cargo boats with wheels) to transfer sling loads—equipment carried in a net— onto the waiting trucks. On OMAHA beach, the “traffic was controlled from a tower,

and instructions were given over a public address system. Luminous markers made night operations possible.”

The work was dangerous and without end:

The drivers worked long and hard, snatching sleep wherever possible and subsisting on K rations. Because the trucks ran twenty-four hours a day, there was no time for the normally prescribed maintenance. Mechanics salvaged parts from deadlined trucks in order to keep others running. White strips of tape were laid to indicate the cleared roads through the mine

Trucks rumble through a ruined town in northern France. GCMF photo.fields. Sacks of sand were piled on the floor of the cabs as a protection against land mines. German snipers were active for several days, and enemy air raids and shellfire kept all beach personnel on the alert. Rain and mud also hindered the trucking operations.

Sgt. Hobbs and his assistant driver began innumerable round trips from the beach to the inland dumps. To stay awake while driving long hours, my father recited epic poems such as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride” and “The Song of Hiawatha,” which he had memorized as a child.

My father’s one statement about the invasion, “We bivouacked in a pretty little apple orchard a short distance from the beach. I got to use my high school French with the couple

who owned the orchard and their young son,” was corroborated in The Transportation Corps which notes that the “first bivouac area was set up in a large apple orchard near St. Pierredu-Mont.” The LeBrec apple orchard, which recently had been abandoned by the retreating Germany army before being occupied by the quartermasters, is still there.

Because the trip was highly secretive, Sgt. Hobbs probably didn’t know that the Joint Chiefs of Staff visited OMAHA Beach on June 12. The Chiefs arrival was rather anonymous—they climbed out of a DUKW with no fanfare or greeting party so he may have driven by, unaware.

Sgt. Hobbs turned 27 on June 14, a week after D-Day, driving a truck on OMAHA Beach. The 3704th Quartermaster Truck Company soon left the beach and spent the rest of the war following units that were mov-

Modern photo of the Dog Red section of OMAHA Beach, with the cliffs of Pointe du Hoc in the background. Wikimedia Commons photo.

Modern photo of the Dog Red section of OMAHA Beach, with the cliffs of Pointe du Hoc in the background. Wikimedia Commons photo.

ing forward. SSgt. Hobbs carried supplies to the front and wounded and prisoners of war to the rear throughout France, Belgium, and Germany. Since his company was not permanently attached to any one unit, my father said they were an independent truck company, which normally doesn’t exist on the Army’s Table of Organization and Equipment. I have not found records following the 3704th through Europe, and the records might not exist from the company’s independent status; if the records do exist, they are not digitized. My father’s military personnel records were burned in a National Archives fire in the 1970s, so the details in this article may be all I learn of his service. What a research journey it has been, starting with a very important map.

The importance of digitized resources cannot be underestimated. In 2023, the George C. Marshall Foundation began the digitization

of the entire Marshall Papers collection, with the goal of providing access to the individual documents via the library catalog. While this effort will take several years, it’s worth the work and expense to provide access to researchers anywhere in the world.

Before becoming director of library and archives at the George C. Marshall Foundation, Melissa was an academic librarian specializing in history. She and her husband, John, have three grown children, and live in Rockbridge County, Virginia, with two large rescue dogs.