5 minute read

A Somerset Connection By Seth Dellow

A Somerset Connection

TO THE SOURCE OF THE NILE

Advertisement

Despite a level of ambivalence toward his discovery of the source of the river Nile, John Hanning Speke enjoyed a moment of celebrity until ‘cut off in full manhood and in the zenith of his fame’. Seth Dellow tells the story of a remarkable individual.

On the 1st October 1864, the Somerset County Gazette published the events of a funeral that took place only weeks earlier at the Church of St. Andrews in Dowlish Wake, near Ilminster. As the muffled bells rang out across the rural landscape, it was declared that ‘All was in mourning and grief for him who had been cut off in full manhood and in the zenith of his fame’. Attended by over 1,500 people, the residents of Victorian Somerset shared a collective sorrow for the loss of a ground-breaking imperial explorer. John Hanning Speke died a sudden death on the 15th September 1864, the result of a shooting accident in Wiltshire, whilst in the company of his cousin, George Fuller. At just 37 years of age, Speke’s untimely end curtailed his many enterprising adventures.

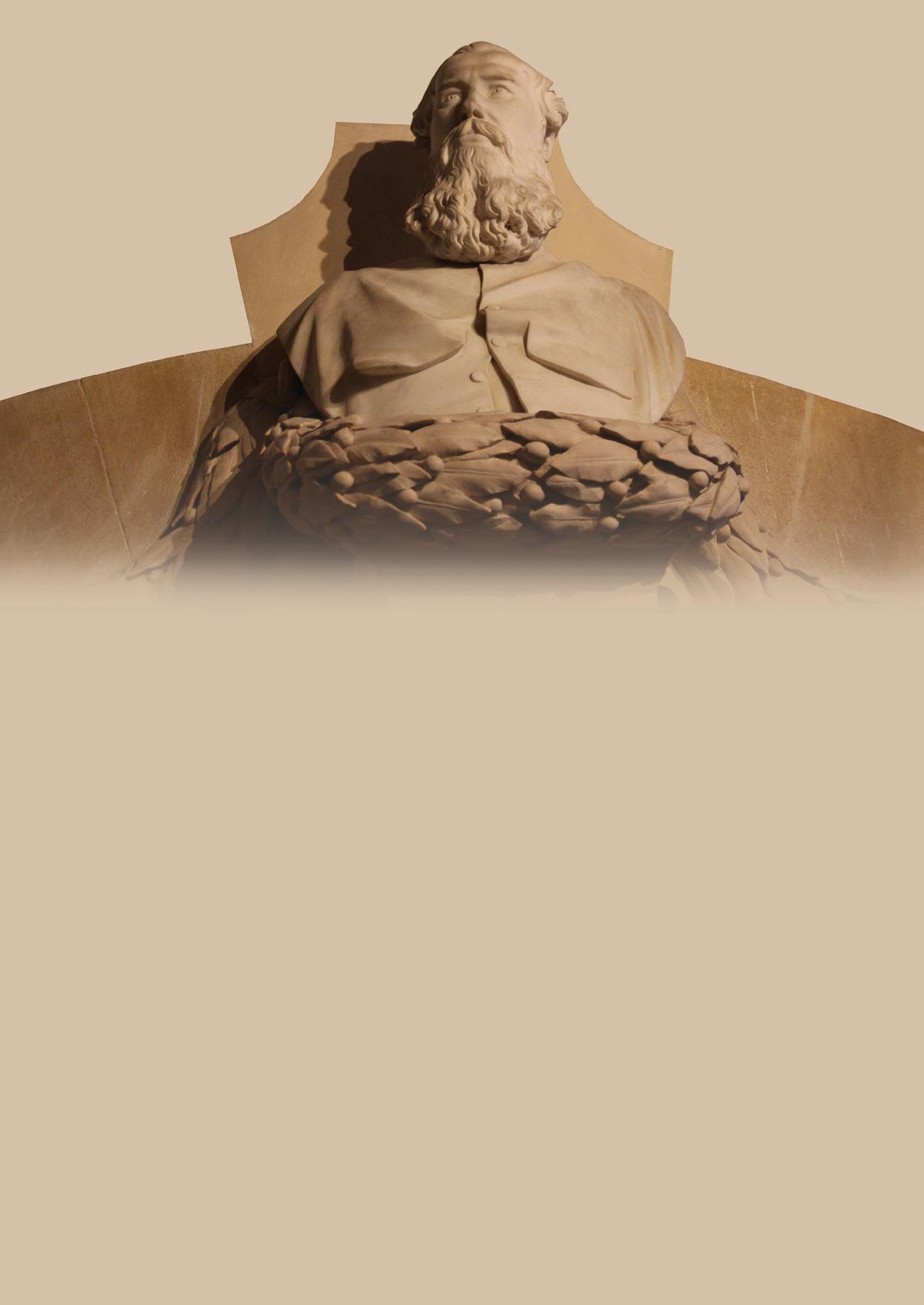

In attendance on that sombre morning were two admired and prolific fellow explorers, both connected by one desire. Dr David Livingstone was a well-known Scottish Christian missionary who explored the African interior in search of the source of River Nile. James Grant was the other, whom Speke had met whilst serving in the Second Sikh War of 1848. Grant became Speke’s loyal companion during his search for the Nile’s source. The mystery of the Nile typified Victorian exploration at its height. Competition was rife between individuals who wished to venture deep into the African continent, with eternal glory and fame the reward. Speke’s ornate memorial within the Church honours his lasting legacy with the inscription ‘E NILO PRAECLARUS’ (From the Nile renowned).

Joining the notorious East India Company’s army in 1844 at just seventeen, Speke was involved in a selection of Eastern campaigns for ten years. However, his disinterest in military endeavours soon drew him to Tibet for years of trophy hunting and specimen collecting. The majority of Speke’s work is now exhibited at the Museum of Somerset in Taunton, in an elaborate room reminiscent of the Natural History Museum. His longing for further adventurous travel took him, in 1854, to the African continent. Within the Church, below the gazing bust of Speke is a semi-circular decorative accompaniment adorned with equatorial animals, including crocodiles and hippopotami. For the increasingly industrialised European powers, Africa remained an enigma. Barely penetrated by outsiders, it represented a fruitful economic and strategic objective, later to be subjected to much imperial might during the infamous ‘Scramble for Africa’.

But for Speke, Africa was the location for a very personal journey, which he wished to explore alone. Yet his first expedition, in 1855, involved the leadership of Sir Richard Burton, a contrasting figure whose miscalculations in hostile Somaliland resulted in being captured by the indigenous Har Owel tribe. Burton, perhaps better known for translating Arabian Nights, was undeniably knowledgeable about the East African interior. Therefore, any further expedition into the hostile, primitive lands would require both Speke and Burton, a duo characterised by suspicion. Amid the Crimean War, a new African opportunity emerged with Burton. The Royal Geographical

Society, founded in 1830, with the proposals of what historian Roy Bridges termed ‘armchair geographers’, the existence of a large lake which could potentially be the source of the River Nile.

Departing in June 1857 from Zanzibar, the sponsored team reached Lake Tanganyika in February 1858. This second expedition was hardly free of complications though. Malaria, desertions, arguments and hostile natives provided many setbacks, travelling at the average pace of only six miles a day. Furthermore, Burton was suffering from tremendous illness and he was forced to return to the coast for supplies. Speke did not follow. Instead, accompanied by a freed slave, Seedy Mubarak Bombay, he continued north in the firm belief of the existence of another large body of water. By August 1858, Speke arrived at an expansive lake that covered 23,000 square miles, reached five countries and was to be ‘his’ source of the River Nile. This was named, in honour of the monarch, Lake Victoria.

Meanwhile, Speke and Burton’s relationship had ended with bitter disagreement. Burton was side-lined as the Royal Geographical Society sponsored Speke in 1860 to return to Africa for a third expedition, this time to verify his headwater claims. Endorsed by Prince Albert, a more robust expedition occurred, partly sponsored by the government who gave £2,500, and the people, who donated an extra £1,200 for supplies. Accompanied by loyal friend James Grant, Speke left with 176 men and armed with previous experience, they pushed further north than before. It was at Karagwe (a Tanzanian district) while Speke was waiting for the expeditionary force to reconvene, that he received an unlikely correspondence. The uncommunicative Kingdom of Buganda heard of Speke’s quest, and its King, Kabaka Mutesa, invited Speke to visit. For his cultural respect, the Bugandans viewed him with prestige. Years after his death, in 1962 following Ugandan independence, his memorial was complemented with a Union Jack flag that had long fluttered in the city of Jinja, on the shores of the lake.

Upon returning to England in June 1863, Speke and Grant were nothing short of celebrities. The Victorian people turned out in their thousands to celebrate the explorers’ achievements. At the Royal Geographical Society’s headquarters in London, several windows were shattered with excitement. In Taunton, a less exuberant ceremony occurred with the ringing out of church bells. The saga of the Nile was not to end here, however. Speke’s publication The Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile, released in December 1863, aroused much ambivalence. The exploratory field became crowded with alternative hypotheses and thus required a public debate. The Royal Geographical Society organised the event in Bath, between Speke and his nemesis, Richard Burton, to be held on the 16th September 1864. Regrettably, Speke’s unfortunate death the day before cancelled the anticipated exchange. Speke’s source of the Nile was only verified years later in 1876, but the memorial where he rests in a serpentine marble sarcophagus is a fitting tribute to a remarkable individual.