4 minute read

janiz chan

Janiz Chan Regrowth

Some sense of place in the time of pandemic

Advertisement

“For me, a landscape does not exist in its own right, since its appearance changes at every moment; but the surrounding atmosphere brings it to life—the light and the air which vary continually. For me, it is only the surrounding atmosphere which gives subjects their true value.” - Claude Monet, 1891

In her latest exhibition Regrowth, Malaysian artist Janiz Chan, explores the sense of place in the time of pandemic through her landscape oil paintings.

For Chan, the place is a contested space between human habitation and nature. In this time of the pandemic brought about by the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19), she discerned the changes in the environment. In the early Movement Control Order (MCO) in Malaysia, she was wondering how the lock-down has affected nature. According to her, “[as] humans are step back, nature gain ground at once, when human advance, nature retreat.”

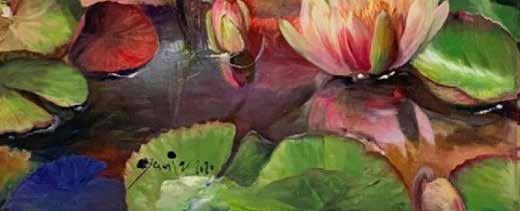

It seems that in her painting entitled Lake Garden, nature has overgrown with trees and plants in varying shades of green, yellow, and pink as well as the pond full of lilies in various stages of blooming. Inspired by the Taman Tasik Perdana (Perdana Botanical Garden) built during the British colonial era in the late 19th Century, the gaps between the lily pads do not only reflect the clear blue skies above but the human intervention to manage the growth of these floating aquatic plants. These gaps suggest the subjugation of nature for human recreational purposes. In the initial phase of this public park, shrubs and local grass called Lalang were cleared and replaced with ornamental flowering trees and shrubs. The Sungei Bras Basah (Bras Basah River) was dammed up to create an artificial lake where the aquatic plants like water lilies thrived in a controlled environment. Manicured lawns, sculptured gardens, deer park, butterfly sanctuary, walkways, and other amenities were added to attract tourists and local residents into this large-scale recreational facility that is much-needed in highly urbanized places like Kuala Lumpur. Indeed, human needs have shaped the form of nature.

Yet in her painting of Kinta Nature Park (Taman Alam Kinta, Batu Gajah), the largest bird sanctuary park in Malaysia, Chan imagines the recovery of nature with the lush green foliage overlaid with water hyacinth and buttercup flowers in blooms and inhabited with unseen species of birds because of the state-sanctioned MCO. But as the light blue boat traverses through the large floating colony of water hyacinth blooming in the foreground, she expresses her concern that despite the lock-down, the human intrusive activities are still present as a real threat to nature’s growth. However, when uncontrolled

by human intervention, this aquatic plant species also becomes a serious threat to the lakes and ponds by affecting the water flow and reducing the sunlight that reaches the endemic aquatic plants in the locality.

In another painting, Chan depicts the lush water lilies in their natural setting at the Paya Indah Wetlands in near Putrajaya. Her depiction of the landscape is a memory of the place. Though the actual wetlands are now uninhabited by tourists and local residents because of the pandemic, the composition of the painting through a small patch of walkway suggests a proposition either to walk, to wade into the waters, to take a boat, and to explore the wetlands, or to leave the wetlands and to return to one’s place without intruding nature’s regrowth.

Either way, there will always be an inevitable interaction between nature and human settlement. As shown in the painting of the water hyacinth with lavender blooms carpeting Melaka’s floodwater retention pond, Chan suggests the mutual relations of “give and take between human [beings] and nature.” In between the lined trees in the middle ground of the painting’s composition, the majestic mosque and Islamic center, Madrasah Al Ridzwan harmoniously towers the landscape of aquatic plant colonies. The architecture and the pond complement each other with the exchanges of their hues of greens and shades of purple.

Thus, in this collection of eight paintings, Chan does not only represent the atmospheric environs of the local parks and wetlands with their greenery and blooms but also puts their true value in her own sense of place that is personal yet shared with nature and her community; contested yet can be negotiated between human beings and nature itself. AM+DG 2020

Jason K. Dy, SJ

Half Ring

PayaIndah