43 minute read

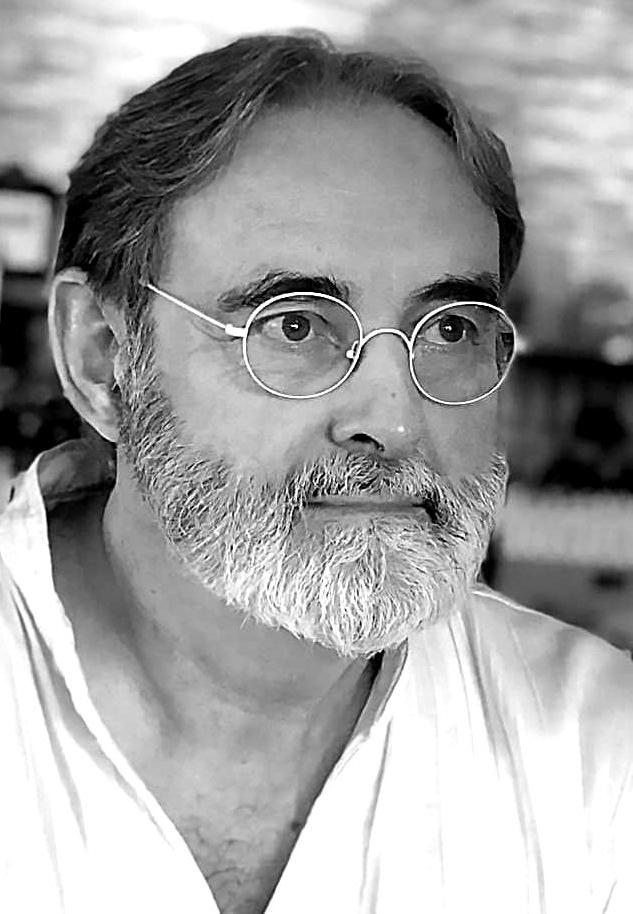

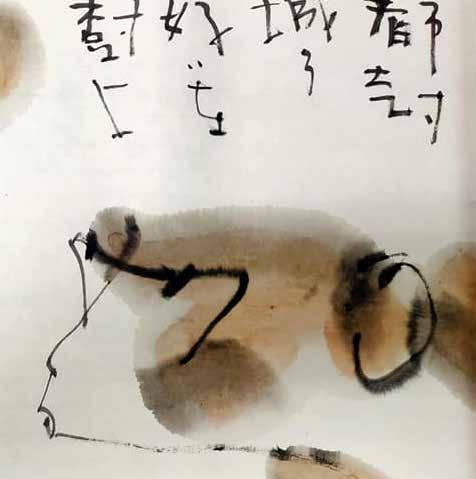

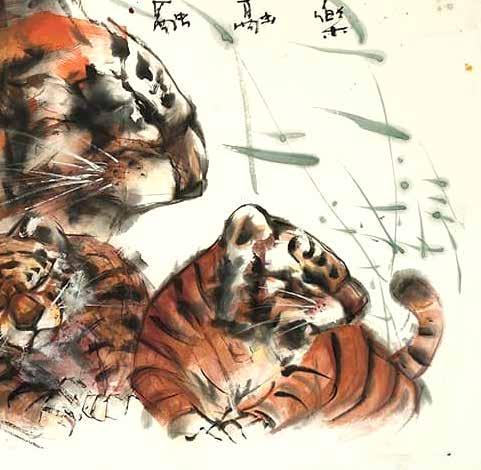

lum weng kong

the passing of master Lum Weng Kong

Advertisement

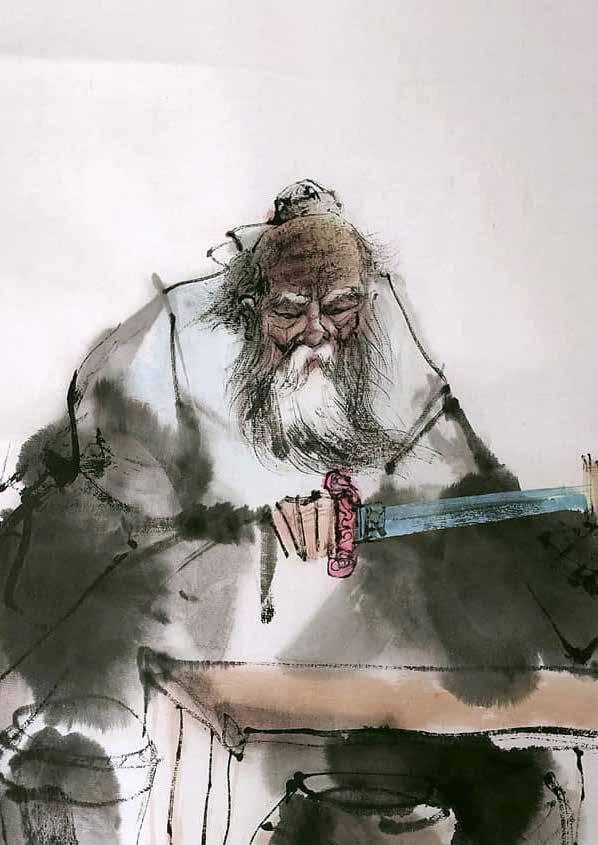

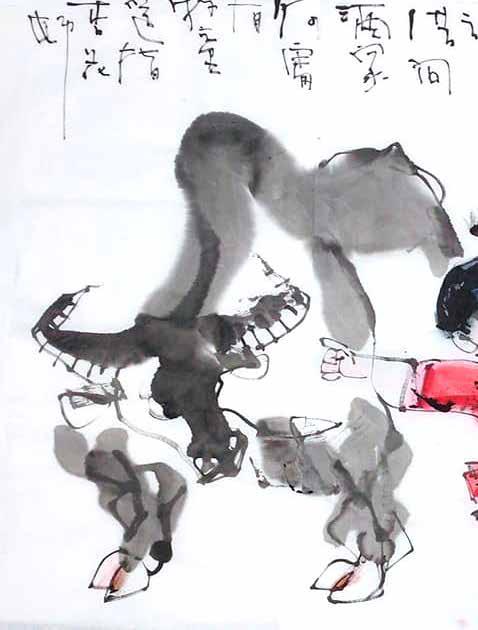

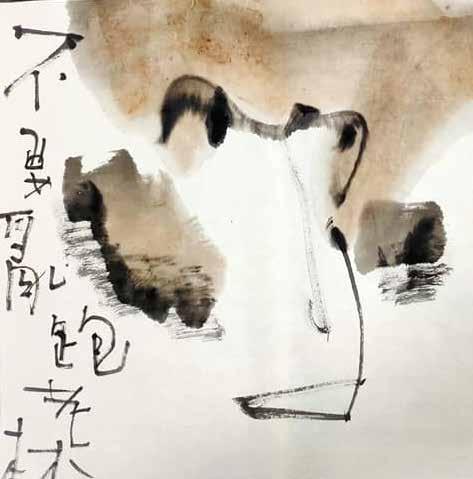

Chinese Malaysian artist Lum Weng Kong, born in 1952, passed away November this year. He was an exemplary Malaysian painter and calligrapher who specialized in the research, creation and teaching of Chinese calligraphy and ink painting. He was committed to promoting and enhancing the cultural ecology of Chinese calligraphy and calligraphy in Malaysia, and insisted upon seeking contemporary concepts in the context of modern culture in the cultural spirit of ancient Chinese tradition.

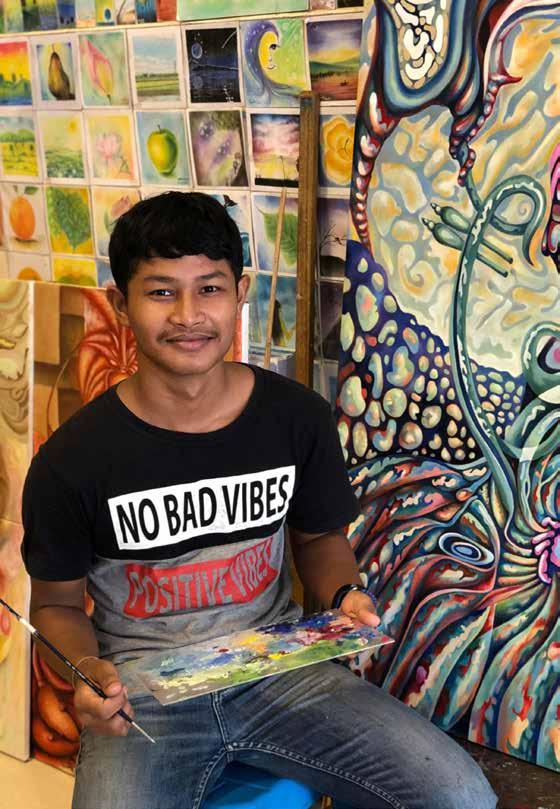

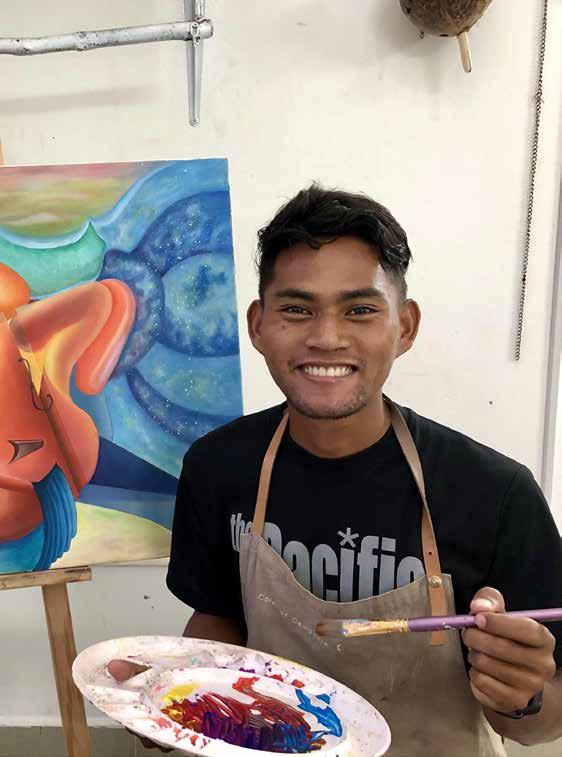

Khmer Seven Teachers at Colors of Cambodia

Seven young Khmer artists Sor Sophany, Thy Channarak, Sorm Narath, Son Kosal, Set Sing, Lem Soleang and Loun Lon, with an age range from 18 to 33 from the charity Colors of Cambodia (began by American artist Bill Gentry in 2003), have grown from students to being teachers themselves and starting the cycle over again and to encourage fresh creativity with the local Khmer community.

During the whole pandemic period of 2020, those seven Khmer teachers have been diligently working towards an exhibition scheduled for December 2020 in Malaysia. Due to lockdown restrictions in place in Malaysia, that showing has had to be cancelled. Plans are being made to have that cancelled exhibition when the restrictions are lifted in 2021.

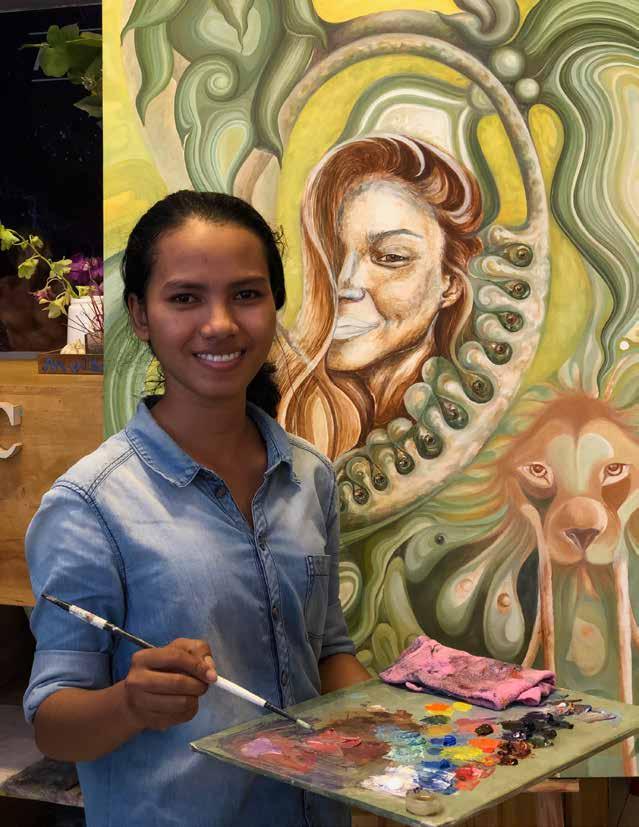

Sor Sophany

Sorm Narath

Set Sing

Loun Lon Thy Channarak

Son Kosal

Lem Soleang

Sor Sophany

I am a Contemporary artist painting mostly figurative work, oil on canvas.

In my works I have the opportunity to talk about my (Khmer) culture and my past spring boarding into the goals of my future. It is in my hands, and your hands too,. For I have given you this insight into my works.

I paint what I recollect from my past, hands down from my family and others. I notice that the past causes some people to suffer, but we are living in the present and cannot change the past, but we can try to understand it, and its power over us.

Thy Channarak

I am a young artist from Siem Reap, Cambodia.

This painting “Nightmare” represents a man considering which of his futures would be better for him.

Dreaming is something that humanity has is common. We sleep at night and awake in the morning. Occasionally, upon waking, we become confused between ‘reality’ and dream. We may even believe that the dream state is reality, and vice versa. However which way it is, that is our life, we must live it day to day. We chose to do so in the hope that our lives will improve. Yes, there are difficulties, and sometimes things happen which we do not appreciate, but he smile and move forward because we chose those initial steps down that road.

Sorm Narath

I am normally a caricaturist, however my painting is a representation of love. The prominent figure is holding and pulling her stringed instrument as she loves and smiles.

Sometimes we feel that people look down on the things we want and those whom we love. People may reject the things which we work so hard at, believing them to be of no benefit, with few results. We find this difficult to accept and, occasionally, want to give up entirely. However we persevere, believe in ourselves and the work that we do and overcome all future obstacles.

Son Kosal

I am a new generation artist. In this artwork, it is my intention is to remind the viewer to be clear when making decisions in their lives, using my imagery as a catalyst.

We know that decisions lead us onto new paths, provoking fresh insights derived from interactions.

Set Sing

I am a Khmer (Cambodian) artist who paints from his imagination with oil, on canvas.

‘Life is a challenge’ concerns the movement, the growth, of the lotus flower and how its symbol interacts within my culture in a flexibility which incorporates visual symbols of growth and harmony.

Commitment, patience are jointly derived from periods of activity and flexibility. When we face problems life becomes difficult. However, solutions do arise in time, leading us to believe that we need not imagine ourselves defeated because although challenging, life continues. We grow like the lotus.

Lem Soleang

I am a young Cambodian artist, and I believe that nothing in our lives is certain as we cannot see into our futures.

People have dreams and goals, but having a dream is not easy. There is always some element of risk, of failure. Alternatively failure encourages greater creativity, and brings hope.

It is said that ‘yesterday is history, tomorrow is a mystery, but today is a gift’.

Loun Lon

The Power of Women 80 x 120 cm

I am a young portrait artist working with oil colours on canvas. I find oil paint is easier to mix to obtain my desired effect.

Because I am a female artist I have noticed that women are always more effected by people around them than men are. I have noticed that women now, more so than in the past, are more self confident , more understanding regarding the power of women.

You can see in my painting that the subject smiles with feminine confidence. In the duality f the painting and expectations of confidence the lion though male never the less portrays the female subject’s confidence.

The Blood Prince of Langkasuka

Tutu Dutta

The monster is not always who you expect it to be.

A re-imagining of an ancient legend; a coming-of-age story of an angst-ridden young man turning into a vampire, while confronted with a chilling murder-mystery.

After an incident involving the cook and a dish of bayam tainted with blood, he discovers that he needs blood to heal and for sustenance.

As heir to the throne of Langkasuka, the prince is also caught in the larger political struggle surrounding the kingdom which is being watched by the two powers of 12th Century Southeast Asia – the Sri Vijaya Empire and the Khmer Empire.

However, a spate of violent deaths in the palace of Langkasuka point towards the prince and his close friends and Raja Perita is slowly driven to breaking point.

When the most powerful shaman in the kingdom is murdered while attempting to commune with the Rice Spirit, the countryside is in an uproar. Her death sets off a witch hunt for a killer who could be a vampire.

Could it be one of the prince’s beloved friends, or perhaps Raja Perita himself?

A classic folklore.

The Blood Prince Of Langkasuka is a re-imagined of a classic story from an ancient times.

The retelling of Raja Bersiong was being told in a very detailed and précised way as possible in this book.

Not only the author will connect you with many other dots that was left untouched whenever people wanted more from this story, you will also be able to understand the whole “reasons and whys” subjects that’ll resulted the whole story, sounded much more sense.

If you have read or heard the famous story about Raja Bersiong somewhere else before this, then you might have lots of questions about the origin of the story, more in-depth elaboration about the whole tale, then this book might just be for you.

I mean, I only heard about this story while growing up, but I have never watch any related videos/movies regarding this tale.

But I can say that this book managed to keep me on my toes. As each chapter was a page turner indeed.

Suspense, mystery and occult all together.

The coverage.

This book covers it all.

Well, at least in a “retelling” kind of way. Because it could be anything else besides what has been told.

Right?

From the time-line, the before story, the after story, the plots, the story building, the people and the overall guide of an ancient Kingdom of Langkasuka.

As we all know, the Malay Archipelago was once a great country of vast and noble Kingdom. An old word called it Langkasuka, but we knew it as Kedah Tua.

As related as it seems, the author tried to re-imagining the event occurred hundred of years passed.

I’m a fantasy, folklore, mystical and mythical hunter. Thus this book got my attention straight-away.

The changes made.

This book might differ a bit from what the original stories was set about or based on what we’re being told, but the original content were there and the core elements were presence in the book. Etc; the blood, the gulai bayam, the siong.

A few other plots were added and few famous yet familiar names were added as well, like Puteri Buluh Betung, Raja Merong Mahawangsa, Kingdom of Khmer and Srivijaya.

Like I said, many parts were improvised to make this book sounded more surreal, sensible while still retaining the initial story of the famous local Vampire.

I would only love it if we will get an in-depth story and strong reasoning for why the main villain acted like how he did as for me it seems like it lacked some kind of firm background story to it.

I won’t say it was random, but it sounded like it was “escalating quickly” kind of plots.

Moreover, I think this book will be a great opportunity if the author would explain, elaborate and expand more about the history of Mount Jerai. It was not just a mountain, but it served also as an ancient monument, a guide to sailors, a checkpoint for travellers and many other legendary stories and events that circles around the Great Mount Jerai. The proud of the North.

Sala Samnak by Lyno Vuth

“Sala Samnak” introduces new works of light installation and paintings by Lyno Vuth created with Kong Siden, Prum Ero and Than Sok. It explores a traditional communal space that exists throughout Cambodia: sala samnak, a rest hall. Sala samnak is part of the fabric of the daily life of Cambodia, and its presence is symbolic of the Cambodian countryside. They are usually modest structures built on the roadside or in the village for passers-by and visitors. In some cases, villagers use it for communal ceremonies or events.

This practice dates back at least to before the Angkorian period. The ancient name of this structure, ‘agni gRha’, translates into house of fire, and possibly refers to the rituals to the divine which took place in it. Today however, many sala samnak structures become neglected and abandoned. Their primordial function, that of offering a rest place for the passers-by and travellers, is replaced by modern cafés and restaurants built along the roadside.

In “Sala Samnak” Lyno is interested in the cultural and social functions of the rest hall and the evolution of its communal function. In one such use, villagers interact and create communal relations through rituals, which take place in the structure. On the other hand, visitors, and strangers may meet and rest together as they commute along their respective journeys. These social relations and chances of an encounter are made possible under sala samnak, which is usually generously built by the villagers.

“Sala Samnak” illustrates the precarious state of these structures and their social, ungraspable aspects. The neon-light installation suspended in the gallery space is otherworldly and reflects a country grasping onto its traditions whilst experiencing rapid economic and social development. This dream-like quality, produced by the radiating blue light, creates an unearthly experience that only appears after dark, hinting at the semi-immateriality and fragility of the structure and the uneven relevance of sala samnak to day.

Without the visitors, the sala samnak loses its purpose and simply becomes an empty space. Every visit to the space is different and it is shaped by the individual encounters of passers-by who will give it its ultimate meaning. Therefore, over the duration of the exhibition at MIRAGE, six paintings of glowing rest halls, represented by six black voids, will be appearing one by one. This ensures that the transient nature and changing character of these ‘rest halls’ will be reflected.

The installation at the MIRAGE Contemporary Art Space is otherworldly and reflects a country grasping onto its traditions whilst experiencing rapid economic and social development. This dream-like quality, produced by the radiating blue light, creates an unearthly experience that only appears after dark, hinting at the semi-immateriality and fragility of the structure and the uneven relevance of sala samnak today.

Without the visitors, the sala samnak loses its purpose and simply becomes an empty space. Every visit to the space is different and it is shaped by the individual encounters of passers-by who will give it its ultimate meaning. Therefore, over the duration of the exhibition at MIRAGE, six paintings of glowing rest halls, represented by six black voids, will be appearing one by one. This ensures that the transient nature and changing character of these ‘rest halls’ will be reflected. To document the evolution of “Sala Samnak”, the visitors are encouraged to share their experiences and memories in a provided guest book and online with the hash-tag #salasamnak. "Sala Samnak", is a light installation and a series of paintings by Vuth Lyno created with Kong Siden (digital rendering), Prum Ero (production and installation) and Than Sok (paintings). It opens on Friday, November 20 at MIRAGE Contemporary Art Space at 6 pm and runs through February 22, 2021. The Artist will deliver a talk on December 6, 2020. Entry to all events if free of charge. The wine reception during the exhibition opening is provided by Les Celliers d'Asie Siem Reap.

black The Works of Bipasha Hayat by Martin Bradley

Black is not exhibited in so elementary a state as white. We meet with it in the vegetable kingdom in semi-combustion: and charcoal, a substance especially worthy of attention on other accounts, exhibits a black colour. Again if woods - for example, boards, owing to the action of light, air, moisture, are deprived in part of their combustibility, there appears first the grey then the black colour. So again, we can convert even portions of animal substance to charcoal by semi-combustion. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Theory of Colours, 1810.

In Bangladesh’s cooler month of February (2019), I had the great pleasure of meeting the former actress and playwright turned artist, Bipasha Hayat, at her home studio in Dhaka 1212. She is the daughter of actor and film director Abul Hayat, and is married to actor and film director Tauquir Ahmed.

Bipasha Hayat has made an international name for herself as a Bangladesh ‘Conceptual’ artist and has turned her attention to one of the most important areas of human existence – memory. Issues of our humanity, identity, self, ‘I’ and ‘Other’, culture etcetera are reliant upon being remembered. In a series of intriguing works Bipasha Hayat has woven a tangible treatise on memory through the colour black.

“Memory of past episodes provides a sense of personal identity-the sense that I am the same person as someone in the past. … the sense of identity derives from two components, one delivering the content of the memory and the other generating the sense of mineness…. In addition, articulating the components of the sense of identity promises to bear on the extent to which this sense of identity provides evidence of personal identity.” Memory and the Sense of personal Identity Stanley B. Klein and Shaun Nichols, Mind, Vol. 121, No. 483 (July 2012) Cast My Vote For Socrates' Acquittal, 2020 Hand-pressed impression with chiselled stone and black acrylic paint on 221 pieces of watercolour paper

Cast My Vote For Socrates' Acquittal, 2020 Hand-pressed impression with chiselled stone and black acrylic paint on 221

Memoir series 2016

In her series of images comprising the installation ‘Cast My Vote For Socrates' Acquittal’ (2020) Hayat references the Greek philosopher Socrates’ sentence of death in 399 BC (B.C.E.). According to the ancient Greek philosopher Plato (in The Apology), Socrates’ crimes were ‘failing to acknowledge gods worshipped by the city’ and ‘corrupting the young’. In her hand-pressed impressions, printed from chiselled stone and black acrylic paint on 221 pieces of watercolour paper, Hayat brings back to our cultural memory the injustice served on one of the greatest Western philosophers of all times. The number 221 references those who voted for Socrates’ acquittal (220), plus her own vote, against the 280 votes for his demise via the drinking of hemlock. The artwork is her vote against injustice, historical and current. Remembering that initial trial, some two thousand and four hundred years later (2012), a new international panel gathered to re-run Socrates’ trial, in Athens and, ironically, acquitted him of his crimes. In other works, such as her ‘Memoir’ series (2016), Hayat uses corrugated cardboard painted black and rendered to intimate words, spaces, sentences, even paragraphs. With raised sections initially ‘reading’ as anonymised and coded segments of ‘text’, the viewer observes what once, from a distance, appears as text recodes itself before their eyes into the corrugated board painted black, which it is. The viewer misreads, mis-recalls and mis-projects images from memory, onto the presented artwork. As the visitor’s brain conjures, clinging to the initial notion of text, desperately trying to make meaning where there is none, their thoughts bid for logic, rationality, and auto-realign to thoughts of Braille (the system of raised dots read with fingers by people having low vision, or who are sight less). As the viewer closes on the artwork fresh recollections occur. Perhaps this enigmatic work, though not text in the common visual sense, can be ‘read’ through touch, though touch is not permitted within the viewing space.

The work confounds and puzzles. Memories dragged up are catapulted at the artworks, hoping that one might stick; that the recalled memory might decode the not encoded. It doesn’t of course. The text, which is not text, only hints at some, seemingly unassailable, language. As intimated by Goethe, charcoal (that which is especially worthy of attention, see above) makes a mark of black colour. Black may be both absence and presence. Black, as text, offers to reveal but as asemic text rescinds that offer in favour of mystery and conundrum. Black can both obscure (as in Hayat’s Memoirs) and reveal. The beauty of faces, of human and animal bodies, of delicate plants, of thought and intention are revealed in the work of artists such as Albrecht Dürer, Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Or, there again, with Chinese black ink made from a mixture of soot and animal glue, such as in the works by Qi Baishi and his ‘ink wash shrimps’ (1951) or the ‘Famine Sketches’ (19431944) of Bangladesh’s Zainul Abedin Mymensingh. While charcoal black, and black ink, may communicate through images and ‘writing’ from the conscious mind, with the intended expedition of acts of communication, there are other ‘texts’ which spring from the subconscious, and which communicate in a less than linear fashion, like the ‘Memoir’ series (above). The making of marks has been intrinsic to humanity from the first cave dwellers, and their awaiting walls, to the black on white text of the hand phone screen. Since early 800 AD with the advent of Chinese printing and later with the world’s first moveable type in China (11th century) we have entrusted our memories to devices and objects exterior to ourselves. We draw, we report, we send and we display but we also save, hold data in our memories, on our computer hard drives and external hard drives. We back up, save to hard copy, preserve memories in books, essays, files, in boxes, on shelves and in rooms because our memory recall cannot be relied upon unless we have eidetic (photographic) memory, which few have. And that was the prompting behind the first Chinese printing, to prompt the oral story tellers. Bipasha Hayat reveals our dependency upon access to memory in her works concerning the use of black and it's innate ability to both reveal and obscure.

While it is generally considered that white reveals and black conceals, when we consider the ‘tabla rasa’, the blank page (probably white) we are considering a background to script, or text or image. If we were to write or type white words onto the white page, we would see little. If, on the other hand, we write or type black words onto that same white page, our thoughts will become revealed.

French Poet and writer Andre Breton was intrigued by the writings of Sigmund Freud and his enquiries into the subconscious mind. Since 1913, Breton engaged in the process of automatic writing and later, with the

Catalogue Korwa par Franck André Jamme, édité par la galerie du jour agnès b., Paris, 1997.

The Treachery of Images (La Trahison des images Magritte.

Catalogue Korwa par Franck André Jamme, édité par la galerie du

La Trahison des images) 1929, René Dadaists especially with Philippe Soupault, furthered his interest in the notions of automatic (subconscious) writing, or surrealist automatism (occurring in the book Les Champs magnétiques The Magnetic Fields, 1920). Breton mentions that…..

“Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express -- verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner -- the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by the thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.”

Later Breton originated the first Surrealist Manifesto (Le Manifeste du Surréalisme, 1924) which outlined his ideas about art and literature concerning the subconscious and the symbolism of dreams. While Breton and others wished to bypass the logical, conscious mind and access the subconscious and its non-filtered thoughts and ideas, they were unaware of one tribal people in India who had no access to literature, but nevertheless produced something the Surrealists would have been amazed by.

The Hill Korwa, living in the Lalarpat and Baladarpat villages in Raigarh District, Madhya Pradesh, India, have no linguistic, written, script. They do, however, produce what has been termed a ‘Magic Script’, that is to say a text-like calligraphy which is not born from language but is ‘painted’ as ‘magical messages’ (J. Swaminathan) by these illiterate tribes people. This Korwa ‘Magic Script’ resembles the concept of asemic writing, generally seen as writing which is a wordless, open, semantic form of writing, and having no specific semantic content. Asemic writing (or script) creates tension. It ‘talks’ about the confusion between the thing seen and the thing it is pointing to, as per Belgium Surreal artist René Magritte and his ‘The Treachery of Images’ (1929) proclaiming that a painting of a pipe is not a pipe (Ceci n'est pas une pipe). This is the area of interest for the practitioners of asemics, in assisting the ‘reader’ to focus on the actual work, its marks and its swirls and to study them for what they are, not for the ‘words’ and their meaning being represented. Asemic calligraphy arranged across draped black muslin in Hayat’s ‘Shadow of Memories’ are reminiscent of Dada and the Surrealist notion of ’Psychic Automatism’. Images rendered onto the draped muslin resemble text, just as the cardboard indentations did in Hayat’s ‘Memoir’ series. Once again the viewer is challenged by the appearance of text that is not text, but the appearance of text. Again the mind wishes to decipher and asks ‘is this the text of another language?’ In Byzantine and Renaissance paintings in the 14th and 15th centuries, there occurred design motifs in certain religious paintings which mimicked, but were not, ‘Eastern’ script. This faux script is known as ‘Pseudo-Kufic’ or

Giotto Madonna and Child (detail) 1320 National Gallery, Washington DC

Lorenzo di Niccolo- St Paul (detail) c. 1400 Legion of Honor, San Francisco decorative Pseudo-Kufic script on the sleeve of the Apostle

Kufesque script. It frequently resembles arabesque styles of lettering, and is painted as embroidered decoration on the hems of garments or edges of carpets in wonderfully detailed paintings. The word ‘Kufic’ explains an early angular form of the Arabic alphabet, found chiefly in decorative inscriptions. The above mentioned scripts had the appearance of, but was not, Arabic. They were representations without textual meaning, and were used for decorative purposes and frequently presenting an "oriental" atmosphere to paintings with regard to individuals or, in particular, Holyland scenes. Hayat’s ‘Shadow of Memories’ ‘script’ is hand rendered. To all intents and purposes is ‘in the wind’. The installation’s black muslin has the possibility of a fluidity of movement of, essentially, throwing its ‘text’ to the wind, making it tentative, possible, but uncertain just as the script itself appears laden with possibilities, but remains an enigma and undecipherable. Those works of Bipasha Hayat are the antithesis of the idea of Tibetan prayer flags, which traditionally are hung in high places to catch the wind so that the Buddhist prayer is carried to bless all sentient beings. Hayat’s works proffer but rescind. In Hayat’s ‘Shadow of Memories’ there is also the sensation that we might be looking at the darkness of memory loss, through degenerative diseases like Alzheimer's, where working memory and long term memory are affected early and where sufferers encounter difficulties in the retelling and reading of texts. In a sense, we the observer of Hayat’s black asemic scripts are forced into the role of the recipient of a degenerative brain disorder. There is much (deliberately) ‘lost in translation’. Much we cannot quite grasp. We become thrown onto the images that are not words, like films in languages which we do not understand, sans subtitles to guide our otherwise active mind (s) through the complex plot twists. There again, we are faced with something resembling the fascinating non-textual, but illustrative, ‘magic scripts’ of the Korwa. Yet Hayat’s work does not use her asemic imagery as an exotic decoration like the pseudo-kulfic script, but more like an offering akin to the Korwa’s ‘magic scripts, and with her works we, her audience, are forced to accept that there may be meanings other than those we can effectively grasp as she intrigues and teases her audience with hints.

Shadow of Memories’

Vietnam

Terri Chong

The photographer

Born and grew up in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Terri Chong is a self taught entrepreneur and photographer who has travelled in and out of China since year 2000 in search of a better life for her family, herself and to realize her many dreams. Her frequent travels and her growing up in a poor family incurring a struggling childhood have brought her face to face with many challenges and hardships in life. However, all these did not deter her from continuing to chase her dreams. Back then, China was a land less travelled by people and this is where her pioneering spirit has led her to where she is today. Looking back, she can still remember people said, “if you can survive in China, you can survive anywhere”. And she survived despite all the obstacles which almost made her gave up on her dreams! Throughout her years of travel around China, from big cities to small remote villages, she has come into contact with poor and abandoned old folks, children and poverty stricken people. Through it all, she has seen and learnt much about the value of life. Humanism and street photography being her forte, most of her photographs cover the real life of people both in the cities and remote places. She captures emotions and expressions of people, with some of her better portraits showing no faces, just expressiveness of body and gestures. She feels alive whenever she hits the back streets, alleys and places less travelled, where many stories are found, emotions are stirred. To her, these scenes are life inspirational and soul searching. Day or night, dimly lit, some lifeless, most alive….the streets and back alleys especially those in China, Hong Kong and Vietnam exudes a certain kind of beauty that has long captivated her heart. Today, one of her ultimate dreams is to be able to share her stories of these experiences as a photographer and artist with the world. She hopes to successfully move her viewers with her photographs, touch people and make a difference in their lives as she captures the life moments of those whom she comes into contact with around the world.

“I see my past in the present through my photography. It is my love affair with life!”

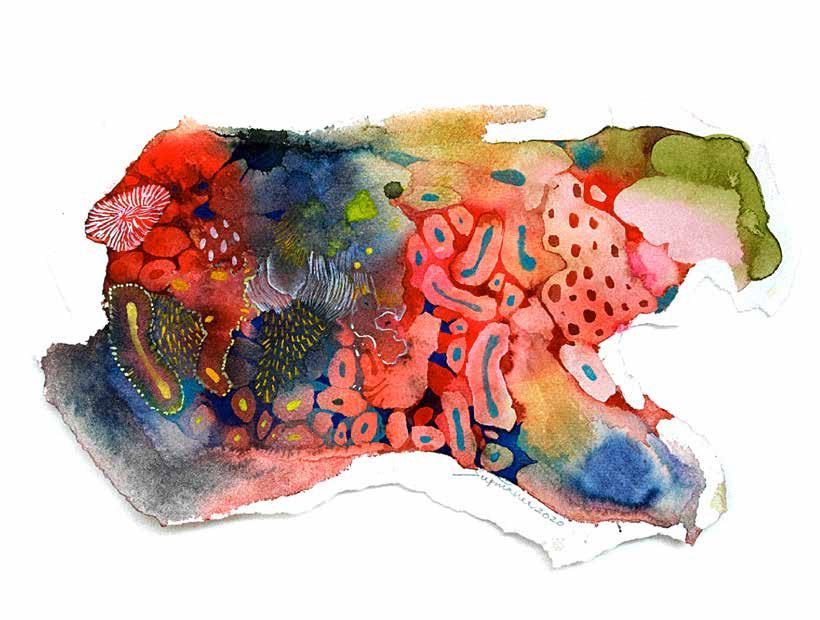

Supmanee Chai garden of the sea

Supmanee Chaisansuk

Was born and lives/works in Bangkok, Thailand She earned a Bachelor of Science Degree (Architecture) and a Master of Architecture (mainly in Architectural Technology & Environmental Design) from the Faculty of Architecture and Planning with Thammasat University in Thailand. She worked as a sustainable architect in DTGO group of company for 8 years and an assistant project manager in Arsom Silp Institute of the Arts in Thailand for one and half years. Currently she works as full time artist with it being the most important thing in her life which she loves to do. She has passionately and energetically practiced exploring innovative art styles inspired by observations in nature.

Artist’s Statement

My concept of artwork is inspired from nature because of my experiences. My home is a local house located in the central business district of Bangkok and surrounded by a naturally green area and ecology which cultivates my desire to appreciate the beauty of nature. I always favour to zoom in on patterns of wildlife such as trees, herbs, fungus, stone, flowers, small creatures, etc. I feel peaceful in my mind and impressed when I look at gorgeous life, so they are my source of art inspiration. Water media technique has been my method for creating my art since I was young, coming from watercolour because of the sense of nature flowing and free of colour and water movement . This approach creates semi-abstract styles as experiments which link natural pattern colours and mind by paint from imagination and subconsciousness to communicate feelings with environments..

Sn silver by Martin Bradley

As I write

I am somewhat displaced. Outside, lanky bamboo canes wave in the evening breeze, while birds vie with distant children’s voices, to be heard. It’s 5.30pm and the sun is reaching its nadir. I am in Siem Reap, Cambodia, caught with the closing of borders some eight months previously due to the Covid 19 pandemic. I came for four days. I have stayed eight months. I am no longer living in Malaysia where I have spent sixteen years. I find myself a tad curious about the future.

In Malay, the word ‘perak’ means silver. Not silver as in the precious metal, but silver the colour of processed tin (Sn, the initials of Stannum) which is derived from cassiterite or tinstone (tin oxide mineral). In 1903, Richard Alexander Fullerton Penrose Jr. the American mining geologist and entrepreneur had written that …

“Perak is the largest producer of the Malay states, supplying considerably over half of the tin of the peninsula, and the Kinta district is at present the most important tin locality in that state…”

There are question marks concerning the origin of ‘Perak’ as a Malaysian State name. Antique maps (imagined by cartographers ancient and modern) suggest that the riverine ‘State’ drew its name from its essence - the Perak river (Sungai Perak) that cuts a swathe through the state. That river has, for centuries, been a resource of tin.

Tin had been mined from alluvial deposits (in Malaya) for some hundreds of years. Well before the 1500s Perak tin was used in Malay ingots and coins. Some ingots and coins were cast in the shape of animals; predominantly fish in Perak while later (1800s), tin was cast as coins or pendants bearing faces. With the advent of greater trade with the outside world (China, India and with people from the Arabic lands), tin coins gained Chinese attributes and/or Arabic writing.

Today, Perak, its Kinta Valley (written about by Tash Aw) and its surrounds brim with luxuriant green. The deep blue of the equatorial sky is reflected in man-made lakes (mining pools) teeming with silvery fish and visited by man and wading birds alike. The ‘lakes’ are tranquil, placid places. Places a thoughtful person might visit to gain a life balance, to become like the waters, unruffled. That is now, but before…..

Due to the world’s hunger for tin cans, pewter and electroplating, Malaya’s tin mining grew to represent over half of the world’s tin output. Tin mining

grew from the simple open-cast mines of the racial Malays to, in the early to mid 1800s, larger scale workings, with thanks to the influx of thousands of migrant miners from China (mainly Hakka, via Penang). As the British took over tin mining in the early 1900s, they co-opted giant mechanical dredges to tear up the peaceful earth, and rent asunder nature’s habitat in Malaya’s (Malaysia’s) green, tropical Kinta Valley countryside. The result was huge holes which, due to nature’s good graces, eventually in-filled with water to form man-made lakes.

I was there, in what was Malaya but is now Malaysia. I had an old, chipped, white enamel (tin) mug since I’d been in Malaysia (about sixteen years). That mug was chipped when I bought it, downstairs in the weekly Amcorp Mall Sunday flea market and it, curiously, reminded me of England, of my growing up around the old Roman town of Colchester, in the much simpler post war 1950s. The mug is nothing special - just white enamel over tin with a blue rim but, as I say, it’s nostalgia. It still reminds me of those ex-British Army soldiers’ enamelled tin mugs, tea…. drinking.... for the use of. Before my unwitting residency in Cambodia, I had finally ended up in Puchong city, Selangor, Malaysia. Puchong is not at all posh. It had been home to Orang Asli (indigenous peoples), then to immigrants from Java and Sumatra and finally to Chinese tin workers back in the day. But, like in the West, the old working class areas have slowly become gentrified. Puchong now has endless (mostly Chinese) shops and work units as well as one large department store (Tesco), and a good-sized mall (IOI Mall) if you like malls, that is. There is also a select restaurant area called Setia Walk that sells meals twice the price and half the worth of the ‘DG’ Food-court not three minutes drive away. It was a vast difference from my quiet bungalow outside the small provincial town of Malim Nawar, in the northern State of Perak.

Previously, in those seven years in Perak I’d been mooching around, writing. By an odd quirk of fate my first Malaysian short stories were published by ‘Silverfish’ (established in 1999), from out of Bangsar, a suburb of Kuala Lumpur. In Perak, I watched early morning fishermen catch silvery ‘Ikan Jelawat Putih’ or ‘White Sultan’ fish from that artificial lake across from my bungalow, marvelling at their patience. Sometimes, a fisherman would take a small wooden boat out onto the lake, casting a net, at other times another fisherman would don his thigh length waders and stride out to catch the silver scaled fish.

Tin, that silvery metal, for me was not just that enamelled mug but thin metal needing soldering. In Colchester’s St. Helena Secondary School (of the early

1960s), boys were given two choices. You could either make things of wood, or of metal. The girls got cooking, which isn’t fair. I’d have much preferred cooking. Cooking is so much more practical than wood or metal work, well it has been for me since my late teens.

I failed miserably at woodwork. Woodwork was all splinters and jamming odd shaped wood together into joints and hoping against hope that they remained together. Mostly mine didn’t. I was swiftly moved to metalwork. I only fared a little better with metal - the metal being tin. It was light, easy to cut and joints were arrived at by soldering, that is melting a metal wire (usually a mixture of tin and lead with a low melting point) onto two pieces of tin and, walla, they were inseparably joined. Though, to be honest, mine were not always that inseparable. My metalwork skills could be compared to my woodwork skills, in other words, negligible.

I was to stay ineffectually metalworking until a new year brought the opportunity to work with plastic. My brief introduction to the ways of tin was over, as had been those of working with wood. I had no idea where tin came from. In my school days Malaya was associated with ‘Emergencies’, “Communist Insurgency’ ‘National Service’ and boys’ dads not coming home, all eloquently written about by Anthony Burgess (The Long Day Wanes) and Leslie Thomas (Virgin Soldiers). Plastic was much more my cup of tea, so to speak. What with the manufacture of plastic shoe horns, the warm bending and all that polishing using an electric buffer, it was a young schoolboy’s delight. And yet, to this day, some fifty plus years later, I have never felt the yearning to make anything from plastic, tin or of wood. But I do cook most days.

My mum, bless her, cooked cakes with sink-holes which, I now realise, strangely resembled Malaysian mining pools before they became in-filled with water. A cake would come fresh from the oven, perfect, a delightful shape and yet, within minutes would develop a crater. It was if some unseen spiritual or mystic force hastily mined each cake.

Mum was born in 1918.Throughout her life my dad would say that she was the reason the ‘Great War’ stopped. Mum was a native of England’s Surrey (Epson). My dad, born in 1919 (one year after the war had stopped) had been dragged up in Norfolk’s silvery herring fishing settlement of Great Yarmouth. As far as I can tell, dad’s mother never did divulge the man who helped create him. That secret went to the grave with her. Oh, there was much speculation, including a man referred to as Mr Percy Strange, but I don’t think he was a doctor, much less a mystical surgeon with Himalayan and occult connections.

Dad’s mother kept her maiden name - Bradley until her marriage. That’s

the name on dad’s birth certificate and mine too. My paternal Grandmother struggled on Yarmouth’s ‘Rows’ - 145 very narrow streets which ran parallel to each other with small terraced houses abutting beach pebbled streets so narrow, that special handcarts (Trollcarts) had to be made to move among them. Regular horse carts were too big. Grandma’s life was, by all accounts, difficult. In the second decade of the Twentieth Century, working-class single parent families had it hard. Yet, in many ways, that hardness may have been offset by the custom of men working on the ‘boats’ while the women were left on the land. There was also the dreadful aftermath of the Great War (1914 - 1918), with women widowed and other children fatherless too. Growing up, I was led to believe that my paternal grandfather died in a submarine during that Great War. It was a convenient untruth. That untruth was perpetuated to stop me from questioning dad’s parentage. The truth was eventually revealed to me by my Aunt Doreen, dad’s half-sister, one fateful day in Gorleston (Gorleston-on-Sea) where she lived with my Uncle Ron and half-cousin Susan. I was in my twenties by this time.

“Tha say ‘e were one Percy Strange, anda dead ringer for your far ‘e were.”

“But dad’s dad died in a submarine, during the first war, didn’t he.”

“Yew old enough ta’ know tha’ there mardle wert made.”

“It was a story. Like a lie.”

“Marty, tha’s a little harsh.”

“Sorry, but it was, wasn’t it. A lie, I mean.”

“Hold yew hard! Ya know ya dad, ‘neath all that putting on parts ‘I was a champion boxer in the army’ stuff, e’sa very sensitive man, anda masterous story ‘bout yon granfar and ’t submarine suited a purpose an ‘e won’t ‘ave truck wi’ nothing else.”

I’d been intrigued. Sure I was a little upset that mum had lied to me about this. Dad never spoke of it. But I was old enough to want to know more.

“Howsomever, Marty, that there’s where story ends. Accordin-lie t’were couple

o sightings of this ‘ere chap, this Mr Strange as e may ‘ave been, in Hunstanton ‘couple arternunes one week. T’ name may or may not be real you know. T’were suggestion passed down by that there old Joe, he what lived o’er Heacham way, family fren your granmaw’s. He say this chap were t’ spitting image of ya father, much older of course.”

And eventually I was muzzled. Sleeping dogs left to lie. Right now, before we go any further, I ought to just mention that I really hate being called Marty.

Grandma was a ‘herring girl’. She and others gutted and packed the herring fish, known as ‘Silver Darlings’ because of their looks, and brought ashore to Britain’s most important fishing port - Great Yarmouth, by specially designed boats called ‘Drifters’.

The silvery Blue Atlantic Herring has been a source of cheap nutrient for thousands of years. Herring (Clupea harengus) can be eaten fresh (though bony), filleted and pickled (as Rollmöpse - an hors d’oeuvre), salted or smoked as bloaters (whole smoked herring), buckling (smoked whole but without the head and usually including the roe), or as kippers (filleted herring smoked). I confess that, in the 1980s, I had a mild addiction to Rollmöpse (rollmpos - singular, Rollmöpse - plural). Rollmöpse are pickled herring fillets rolled around a filling, normally pickled ‘Silverskin’ onion, cucumber or sauerkraut. The name hails from Germany. I simply couldn’t get enough. There was always a jar or two in the fridge. But tempus does indeed fugit and the craving, at some point, dissipated.

In a many masted past, Great Yarmouth could harbour up to one thousand weathered herring drift boats lining up. Their masts/funnels would point into the grey, overcast, Norfolk sky while their bowels were being emptied. It would have taken two hardy sea men to handle each of the wicker baskets filled to the brim and over spilling with the silvery herring. Men would have trudged from boats to wooden fish troughs, emptied fish for the Scottish migrant ‘Herring Girls’ and local women in their drab cotton clothes to begin their unenviable task of cleaning, salting and barrelling the fresh fish of the day’s silver ‘Herring Harvest’. For centuries herring had been plentiful, seemingly inexhaustible. Fortunes had been made in their fishing and, some say, that they had been the backbone of early northern-European capitalism. But by the early twentieth century herring had been overfished. Just as, in Malaysia, there had eventually been a glut of tin, and a collapsing market.

I have no concrete idea of my paternal Grandma’s struggle, but to be poor

and a single parent in the second decade of the twentieth century, with sparse education, must have been extremely difficult for her. Her life was a far cry from the lives of the visitors to Yarmouth’s ‘seaside resort’, the ‘Pleasure Gardens’, the Boating Lake’ and the ‘Waterways’ (incorporating the Boating Lake and the new Venetian Waterways, and designed by Borough Engineer Mr S P Thompson, in 1928). My dad, in his growing years, offered his services porting fish and fish discards around Great Yarmouth wharfs, just to earn a little to help his mother. Occasionally he attended school, or sometimes helped out as a ‘Tally boy’ writing labels for boxes on the sea-faring Drifters.

I hardly knew my paternal grandmother, or her husband Mr Littlewood, by whom she had three children after my father, Albert, Doreen and Ray. My chief recollection of Grandma was rabbit stew with Norfolk ‘Dumplings’. On the rare occasions that my parents could afford to travel between whichever town in Essex we were stationed in at the time, via motorcycle and side-car, to Grandma’s small council house in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, Grandma made rabbit stew. In that murky stew floated dough dumplings of flour, suet, salt and pepper. I think it was my father’s favourite meal, either that or the cheapest stew available during the late 1950s/early 1960s.

Being of dubious parentage, my dad spent his young life in a Merchant Navy Hostel for boys, in Great Yarmouth. He graduated to sailing the seven seas as a young Merchant Navy sailor then, when old enough, was accepted into the army - the Royal Norfolk Regiment, which was then sequestered in Norwich. Between his sailing days and his army days, my father pretty much toured the entire globe from North America to Africa and India, and bits and bobs inbetween, but not to Malaya (Malaysia). My mother’s father was Liverpool Irish, just like The Beatles. He went by the nickname of ‘Bonner’ (in Irish ‘O’Cnaimhsighe’, meaning midwife). I never met him, nor his wife, my maternal grandmother. They had passed long before I was born. I understand that Grandfather worked in the new fangled Electricity Company, but doing what I have no idea. You see, my past is a tangled net, full of holes and in severe need of repair.

I was born opposite Clapham Common, in the County of London. There was no spoon in my mouth, let alone a silver one. When asked, I always say that I’m from London. It’s easier that way.

Being so young when my family moved, I remember nothing of Clapham, nor of Epsom, Surrey, where we moved next. My recollections only begin when we had moved into Mill Lane, Rochford, in the much-maligned county of Essex. No

jokes about Essex girls, white handbags or white stilettos here. My father had a job at Rankin’s Flour Mill, toting bags of flour. My mother worked in Southend (on sea), making electric light bulbs. There were various way-stages on the road to my teens, apple farms, mushroom farms, gentry who reared horses, but by the time I was thirteen we were living in council housing in Marks Tey. I escaped barely four years after.

None of this story is in any way glamorous. My grandparents worked hard, produced children who equally worked hard, and had little or no access to the sort of education which could have pulled their poorly shodden feet out of the soil. It took me until I was twenty-eight to get to ‘Art School’ and then on to university. My mum had left school at 14 years and had become a laundry maid, then housekeeper to gentry and, eventually, the cycle of life deemed that she should be a laundry maid once more, this time in a ‘Home for the Elderly’, in Colchester. We were glad of the bathroom and the inside toilet; things we had severely lacked while in ‘tied’ accommodation.

It took me many misdirections, many winding roads, some lesser travelled but, by the time I had enjoyed my fifty-fourth summer in England, I was determined for it to be my last. With a head filled with romantic notions of lotus-eaters, endless days of summer, exotic women and a great variety of exotic food, I touched down in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, spent a little time there and created my bungalow, where I lived for seven years in the silver (tin) state of Perak. That was before what I thought was to be my finally settling in Puchong, Selangor. It wasn’t to be.

I had come to Cambodia, with its Buddhist temples and smiling inhabitants, and discovered more about myself, some good, some not so. I take each day as it comes, trying to take my eyes off the recent past and what I thought that I had there, and not looking too far into a completely unknown future.

Today, the Phnom Penh Post tells me that silver deposits have been recently found in northern Cambodia, now that’s a coincidence isn’t it.