Power, Politics and Space: Fascist Architecture in Italy and Germany

“Massive dimensions, the splendour of their forms, the richness of materials: the buildings’ physical concreteness, their social impact, and their functional connotations also won the support of people who were indifferent to politics” (Nicoloso, 2022)

Marwa Fouad

BA Architecture Dissertation ARCT 1014

Dissertation Group 1: Architecture, Power and Propaganda Tutor: Laura Bowie Word Count: 6,729

Content I.

II.

Abstract

Introduction III. Chapter One: Architectual Ideology 1.1 Fascist Architecture 1.2 Commonalities between both leaders 1.3 Materials IV. Chapter Two: Use of Buildings 2.1 Case study: Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana and The Volkshalle 2.1.1 Construction 2.1.2 Use 2.1.3 Perception V. Chapter Three: Demolish, Preserve and Reuse 3.1 Attitudes Post-Fascism 3.2 Demolition 3.2.1 Littoriale, Rome 3.2.2 Ehrentempel, Munich 3.3 Preserve 3.3.1 The Art of Ventennio, Rome 3.3.2 Topography of Terror, Berlin 3.4 Reuse 3.4.1 Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana, Rome 3.4.2 Detlev-Rohwedder-Haus, Berlin VI. Conclusion VII. Bibliography VIII. List of Figures

I. Abstract

Abstract

This dissertation evaluates how leaders in the twentieth century, such as Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, promoted their fascist movements through architectural buildings, in order to enforce control over their country and display their power. This was analysed in Palazzo della Civilta Italiana, Rome and The Volkshalle, Berlin, both considered classical architecture. They were able to successfully assist each other in committing propaganda since they both held similar opinions regarding their individual regimes. This was attained when Mussolini celebrated the 10th anniversary of the March on Rome; similarly, when Hitler presented speeches to a mass amount of people about his regime, both in an attempt to gain support. In order to consolidate their positions of power, the regimes had a significant impact on the development of the architectural landscape.

The past and present effects of fascism in Italy and Germany are investigated throughout each chapter. Demonstrating how they both bonded over their regimes, which allowed them to be perceived as similar. This was fulfilled through the influence of Ancient Roman structures, which brought the success of their ideological aims. Therefore, they were able to alter the landscape through the use of architecture, allowing their political system to retain its importance in society.

, II. Introduction

During 1919, ‘classical’ Italy and Germany were formed through the influence of their fascist regimes. Fascism was driven by ideology, generally known as a political movement that attempted to reorient its historical background (Malone, 2017). Both leaders envisioned a “new city” for their countries based on historical structures aiming to reveal their strength and power which, they believed “only the strong could survive” (Alexander, 2004). This was successfully done in Rome as it had a connection to the Ancient Empire that was going to be reborn (Smith, 2021). Whereas, Germany tried to claim Ancient Roman styles, as well as Greek to showcase fascism. Over time, Mussolini and Hitler gained political dominance because of their regimes, which led them to achieve equal holding supremacy (Focardi, 2022). As a result of this, both leaders gained the ability to reform their cities architectural landscapes. This will be demonstrated through two architectural case studies, Palazzo della Civilta Italiana in Rome and The Volkshalle in Berlin. Both of these buildings visually represented classical architecture. Mussolini and Hitler had similarities as leaders and their regimes, which was portrayed with these architectural buildings, however, one achieved their goals more than the other. Mussolini’s intention with Palazzo della Civilta Italiana was to be used in his World Fair in Rome in 1942, where it would have been the centre of attention to showcase the regime (Kessler, 2015). Whereas, Hitler used scale to portray his control (Seraphim, 2013). Models like The Volkshalle represented this clearly, as it was “an enormous hall capped by a dome 825ft in diameter, rising to a height of 954ft with the ability to hold a crowd of 150,000 people that would stand and listen to Hitler speak” (Ladd, 1997, p.137). As a result, his design driver was illustrated through scale, which was supported by the capacity of his buildings.

The aim is to assess how far Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler went as leaders in an attempt to manipulate their own countries into supporting their political regimes, which allowed architecture to be used as a tool for propaganda. As well as questioning the impact the political regime had on the landscape resulting in violence, which is inflicted on the city and its people, and whether it still holds relevance after the regime. Finally, I will examine how these two fascist buildings hold negativity from the past because of the actions their leaders acquired through propaganda acts to reflect power.

I will concentrate on books and articles to gain a thorough understanding of fascism and its impact on my chosen case studies. Malone, H provides an overview of fascism in Italy and how Mussolini’s goal was to use architecture to establish the supremacy of Italian civilisation, which led to it being perceived as a “difficult heritage” of the locals, as well as her theory on demolishing, preserving, and reusing. Another source will be Smith, M.L., which will provide a deeper understanding of how Hitler achieved his goal of redesigning the “new Berlin” through the use of classical architecture.

There will be a focus on three key research questions. Firstly, ‘To what extent has ideology been the key influence for Italy and Germany’s architecture to be perceived as “siblings”?’. This will allow me to evaluate the similarities and differences to achieve

how this has been perceived and if their leaders have been the main influence in the outcome. Secondly, ‘How have Ancient Roman structures had a vital influence on Rome’s landscape, whereas Berlin was swayed by Greek/Roman structures?’. In the same way, this equally shows their similarities and differences in architecture. Lastly, ‘Once the political regime is lost, do these architectural references still hold their importance in society because of the political violence their leaders imprinted?’. Overall, this will demonstrate post-fascism views and the impact the movement had not only on the landscape but the people too.

This will be obtained through different research methods. A textual analysis of primary and secondary sources will be used to trace the key debates between fascism in Italy and Germany, as well as how they are viewed together as a result of their leaders. This will be supplemented with primary sources such as articles to fully understand the key influences each leader had in successfully achieving their ideological aims. Books will be a secondary source I will use; this will allow me to conduct an indepth analysis of other possible causes of fascism, such as the historical past and the impact of the Great War. Moreover, I plan to use photographs to provide a more visual interpretation of both of my case studies. This will allow me to examine the materials, structure, and form of both buildings designed by their former architects in order to understand how they were perceived in a fascist manner.

This dissertation will be divided into three chapters, each of which will discuss the impact of fascism. Chapter one will focus on the ideologies behind the architectural designs such as the background to fascist architecture, commonalities between both leaders and how this was influenced through the use of certain materials. Chapter two will follow how this impacted the landscape through two specific buildings: Palazzo della Civilta Italiana and The Volkshalle: how were they constructed? how were they used? how were they viewed? Furthermore, chapter three will evaluate Hannah Malone’s theory the ‘demolish, preserve and reuse’ scheme. This will be done by comparing and contrasting buildings from Italy and Germany in each scheme, to show their significance and debates about why it happened and the impact.

Introduction

Chapter One: Architectural Ideology

III.

Figure 1: Both Mussolini’s and Hitler’s rise to power

Figure 2: Celebration of the 10th anniversary of the “March on Rome”, October 28, 1932

Figure 1: Both Mussolini’s and Hitler’s rise to power

Figure 2: Celebration of the 10th anniversary of the “March on Rome”, October 28, 1932

Chapter One

Chapter One represents the ideological drivers that led to the development of Fascism. Mainly how history has reshaped fascism to be seen the way it is, to this day. In this instance, two prime case studies are Italy and Germany. Their political leaders, Mussolini and Hitler promoted their power through architecture to display their regimes. In-depth, this chapter will showcase an overview of how fascism arose, how both countries were influenced by one another, and the materials they conducted to achieve their aims.

1.1 Fascist Architecture

Fascism is a political ideology and mass movement that was portrayed through classical architecture. This evolved in European countries between 1919 to 1945 (Malone, 2017). Two prime countries are Italy and Germany which will be the main case studies as they became more similar over time. This was achieved as Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler (figure 1), shared similar views on reshaping their countries and ordering a new set of values to re-educate their respective societies (Alexander, 2004). This allowed Rome and Berlin to successfully build up their movements in 1919, to enable “diverse groups of political and cultural dissidents without imposing a high degree of party discipline” (Alexander, 2004, p.4). Which demonstrates Mussolini and Hitler held similar ideological beliefs, through their mutual desire to rule their respective countries would be successful with each other’s assistance.

Prior to fascism, the Great War, which lasted from 1914 to 1918, left people in need of strong national unity and leadership to retake their country and bring it under their rule. Benito Mussolini saw this as a great opportunity to gain control as it was simple for him to carry out the objectives of his new regime (Eatwell, 2011). This was successful to an extent, as the “regime quickly gained the support of the industrial working class, the middle class and business through political rhetoric that promised social reform, political power and aggressive nationalism” (Lasansky, 2004, p.1). However, this did not give the public an option; rather, it forced them to support it. The first fascist movement arose in Milan, in March 1919, which was the start of Mussolini’s interest (Eatwell, 2011). The term fascismo is attained from the Roman fasces, once carried by the ancient lictors to symbolise strength in unity and state power (Arthurs, 2013). Which captivated Mussolini’s passion in Rome, particularly because of its link to the ancient past, which reflected power. This is portrayed when he vowed “I swear to lead our country one and more in the paths of ancient greatness” (Scott, 1932, p.646), during the celebration of the 10th anniversary of the March on Rome in 1932 (figure 2). He assisted armed squads in black shirts to go down the streets of Italy and intimidate the locals to reflect his control (Tikkanen, 2022). To conclude, Mussolini achieved his ideological goal, as the March allowed him to compel the public’s support, which forced their attention as they had to obey their leader. Mussolini desired to reshape Rome by resurrecting the Ancient past in an attempt to help him seize power in Italy. The implications derived from ancient lictors which portrayed strength and power were sought after by Mussolini; he would adopt these characteristics in order to mirror these connotations.

“What is ugly in Berlin, we shall remove, and Berlin shall now be given the very best that can be made. All who enter the Reich Chancellery must have the feeling that they are visiting the masters of the world…Only this shall we succeed in eclipsing our only rival, Rome. For material, we’ll use granite...In

ten thousand years these buildings will still be standing”

Hitler, Table Talk, night of October 21st-22nd, 1941 (Ladd, 1997, p.126)

Similarly, Adolf Hitler promoted National Socialism in order to transform Berlin into a new city through the use of architecture, claiming that it “shall now be given the very best that can be made” (Ladd, 1997, p.126). National Socialist Architecture was seen as similar to fascism, as they both followed a set of the same rules. Moreover, both were influenced by the classical period, which led them to display similar styles. However, the difference with Hitler is that he depended on the impression it leaves on people to grow and gain recognition, which he achieved as they drew “public attention” (Hagen and Ostergren, 2019, p.6). He intended to accomplish this by demolishing “what is ugly in Berlin, we shall remove” (Ladd, 1997, p.126), redesigning all urban planning, to give a higher image of his power. Achieved through a totalitarian state that would implement his “ideology through every medium of communication” (Miller Lane, B, 1968, p.2), such as, “progress reports, architectural drawings and scale models which were repeatedly featured in newsreels, newspapers and magazines” (Hagen and Ostergren, 2019, p.6). This was done to showcase his “larger than life buildings” (Smith, 2021, p.1), inspired by the classical world of architecture. This was successful as the large buildings served as symbols of power to portray the movement, reflecting his fascist approach (Seraphim, 2013). ). Overall, Hitler achieved his goal to an extent, as he managed to gather ideas on how he wanted to reshape Berlin to make it a ‘new city’, but damaged his reputation as well as the political regime through the use of propaganda, that led to the destruction of World War Two.

1.2 Commonalities between both leaders

The term ‘ideology’ is typically considered to refer to a structured system of beliefs and ideas designed to address issues and enact significant change to reflect power (Lee, 2016). Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler both used ideology to their advantage to reflect control in order to reshape their countries. They both transformed the government to a totalitarian state, to gain complete control over the public (Lytteltom, 2004). Adolf Hitler was passionate about architecture, but it served as a supplement to his expertise in erecting propaganda through skilful oration (Smith, 2021). This meant that he saw an opportunity to gain more recognition through his interests. Similarly, Mussolini ensured fascism was embedded into the buildings, which acted as a tool for the regime (Kessler, 2015). This shows that they both grew a fond interest in architecture, which allowed them to achieve their propaganda aims. Propaganda was displayed in campaigns consisting of film reels, magazines and political rallies (Kessler, 2015). In order to commit these acts, both leaders believed that “politics violent struggle...which only the strong

could survive” (Alexander, 2004). Therefore, this mindset empowered them to think they were superior and stronger than everyone else which allowed their leaders to rapidly act on their ideologies (Alexander, 2004). For that reason, it is believed that the relationship between the two rulers demonstrated “a powerful political dynamic which has a direct impact on European politics” (Focardi, 2022, p.44). From the European point of view, their friendship allowed them to grow in a similar way, where they were portrayed as “siblings” through their movements (Focardi, 2022). This demonstrates that Mussolini and Hitler both used propaganda to advance their fascist regimes, believing that their roles made them superior to others.

1.3 Materials

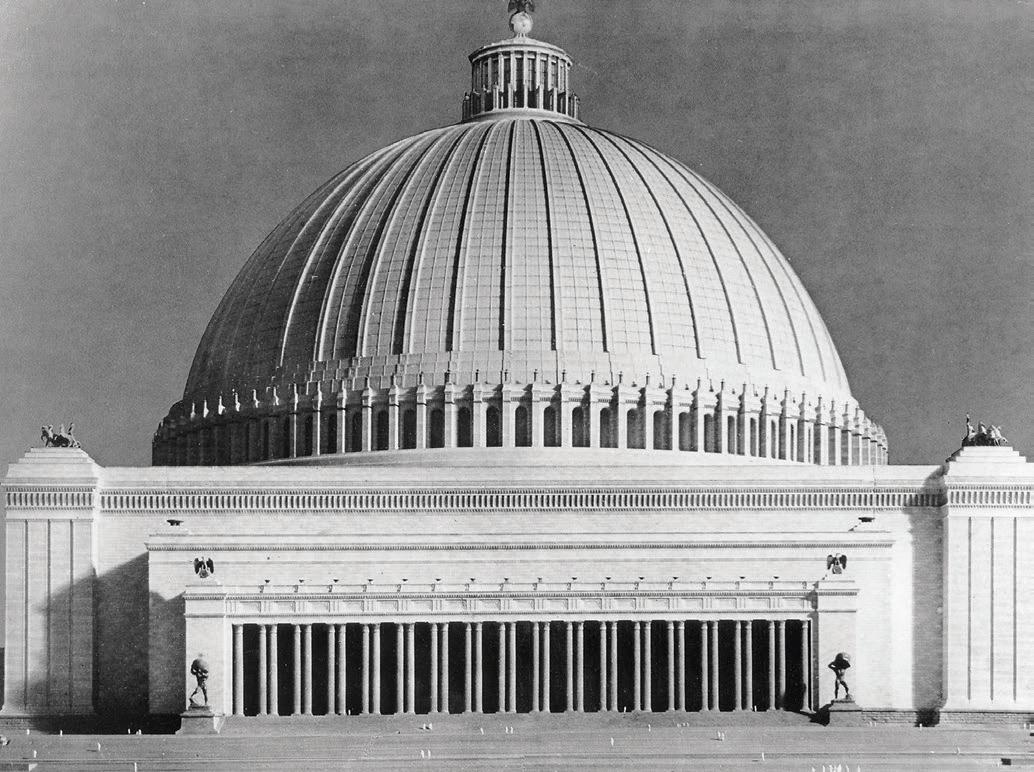

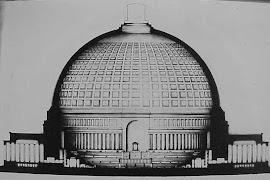

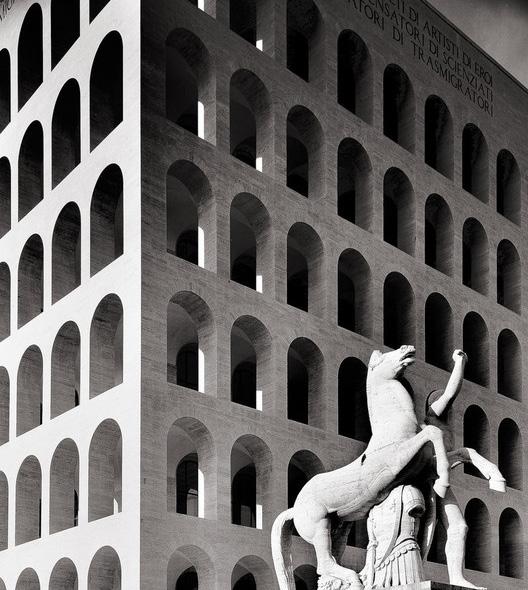

Classical architecture was the main influence which was visible in the architectural designs. Although they both followed the same design structure, the Ancient history in Italy was far less complicated than in Germany. This is because the city of Rome itself had an established history with the Roman Empire, whereas, Hitler attempted to claim Greek as well as Roman history into the German heritage to showcase fascism (Smith, 2021). As a result, it was commonly referred to as ‘GrecoRoman,’ shown in figure 4, the combination embodied a sense of stability and freedom (Scobie, 1990). This demonstrates how National Socialist architecture represented Adolf Hitler’s desire

as a dictator, as well as restoring Germany’s power and culture during a time of conflict (Smith, 2021). In attempt to portray classical architecture, the aim was to construct a sequence of colonnades from natural stone, to illustrate monumental classicism (Kessler, 2015). This can be seen in the Volkshalle model, presented in figure 3, through the use of columns at the building’s entrance, which is similar to figure 4. This reflects Greco-Roman architecture through the use of columns and symmetry.

“We dream of a Roman Italy, wise and strong, disciplined and imperial. much of what was once the immortal spirit of Rome has risen again in Fascism: our Littorio is Roman, our military organisation is Roman, our pride and our courage are Roman”

Mussolini, Marking the 2,675th anniversary of Rome’s founding, April 21st, 1922 (Arthurs, 2013, p.1)

Fascism was sculpted with “arches and columns” (Nicoloso, 2022, p.5), these features were easily recognised by people due to the Roman connotations. This is significant because the desire for attention would have been the primary motivator for them to achieve their ideological goals. The use of columns reflected solidarity and strength, which attained both rulers’ ambitions in order to successfully achieve propaganda. Caesar Augustus, the first Roman emperor, made use of the past while in power. He adequately reorganised and reoriented Rome. This made the Roman identity feel unique in comparison to other ancient cultures (Smith, 2021). A few months following the gain of Benito Mussolini’s new title as ruler, his “dream” turned into political violence. The fascist regime aimed to promote propaganda, in attempt to refashion Italy into a political nation guided by “the immortal spirit of Rome” (Arthurs, 2013, p.1), as it was his pride and joy. This shows Mussolini intended to carry on the Ancient Roman structures from the past to reshape public monuments and buildings virtually for the community. He aimed to “rehabilitate fascism through historical revisionism” (Malone, 2017, p.445), in the urban designs, structures, monuments, plaques, and street names that can still be seen in Rome’s landscape. This was successful to an extent, as the use of ancient structures gave the illusion of stability, but Mussolini aimed to diminish human rights to achieve his propaganda.

Both movements emerged in 1919, which combined groups of political and cultural dissidents (Alexander, 2004). By the 1990s, Italian fascism and German National Socialism were well known as two “classic” examples of the fascist “beast” (Eatwell, 2011). For example, Sybille utilises the concept of “spaces” to display the role of violence in the two regimes (Focardi, 2022), which was stated in the spatial dimensions produced by the Nazi regime. Mainly expressed through the use of place, space and architecture. Hitler regarded his structures as political props, meant to both impress and humiliate the German people. This was achieved by insisting on speeches in his architectural buildings to discuss his political regime (Hagen and Ostergren, 2019). This humiliated his people as it disregarded them and made Hitler appear superior, which was his intention as they had no choice but to support him.

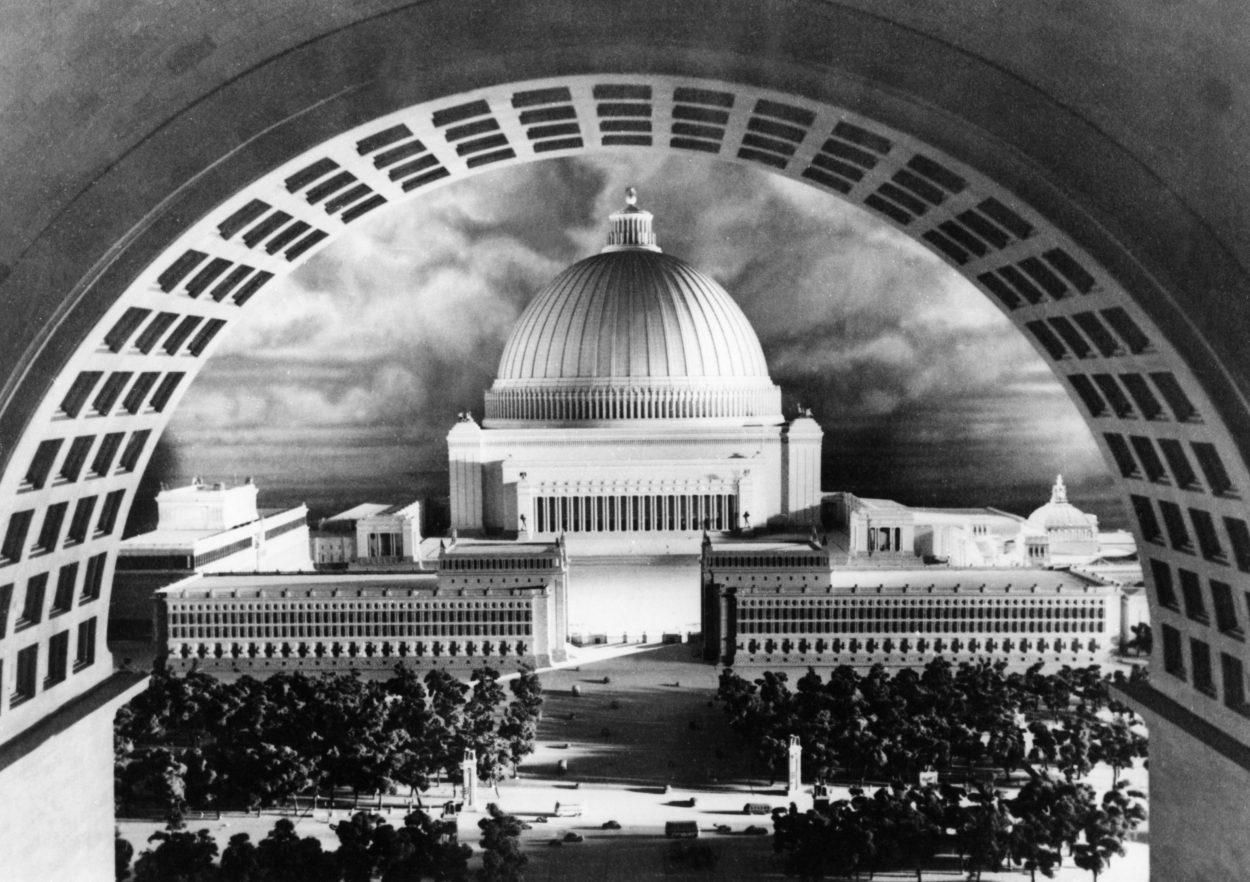

Figure 3: The Unbuilt Nazi Pantheon: Albert Speer’s “Volkshalle”

Figure 4: Greco-Roman Architecture

Figure 3: The Unbuilt Nazi Pantheon: Albert Speer’s “Volkshalle”

Figure 4: Greco-Roman Architecture

This chapter evidenced that fascism served as an ideological motivator for both leaders to assert their dominance. This was accomplished through Ancient structures. Ancient Rome had a significant impact on both leaders as it projected a sense of strength and unique identity. As a result, they believed they were stronger than others in order to achieve their goals. Their leadership mindsets led them to believe that only “the strong” could overcome the challenges they encountered.

Chapter Two: Use of Buildings

IV.

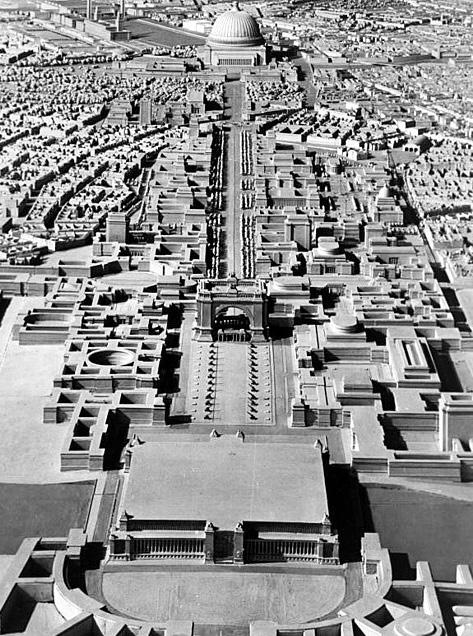

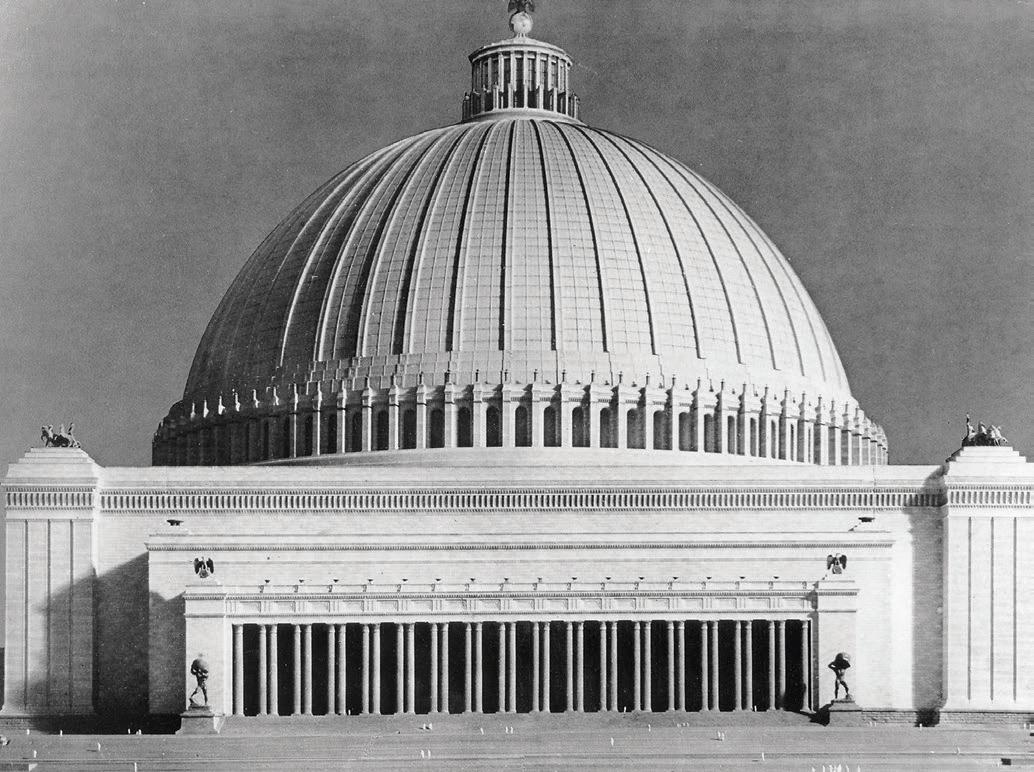

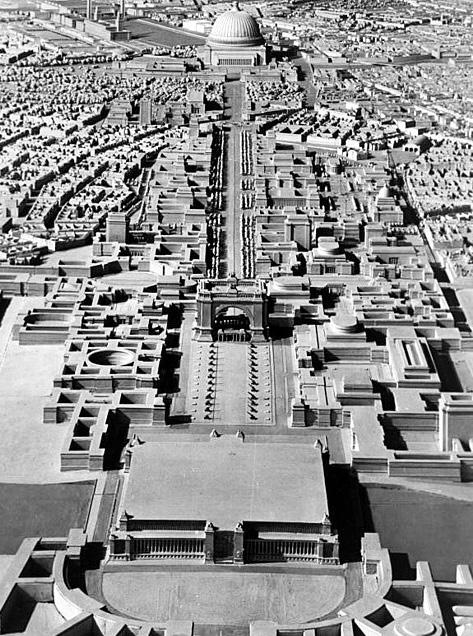

Figure 5: The Volkshalle’s Great Dome can be seen at the top of this model of Hitler’s plan for Berlin

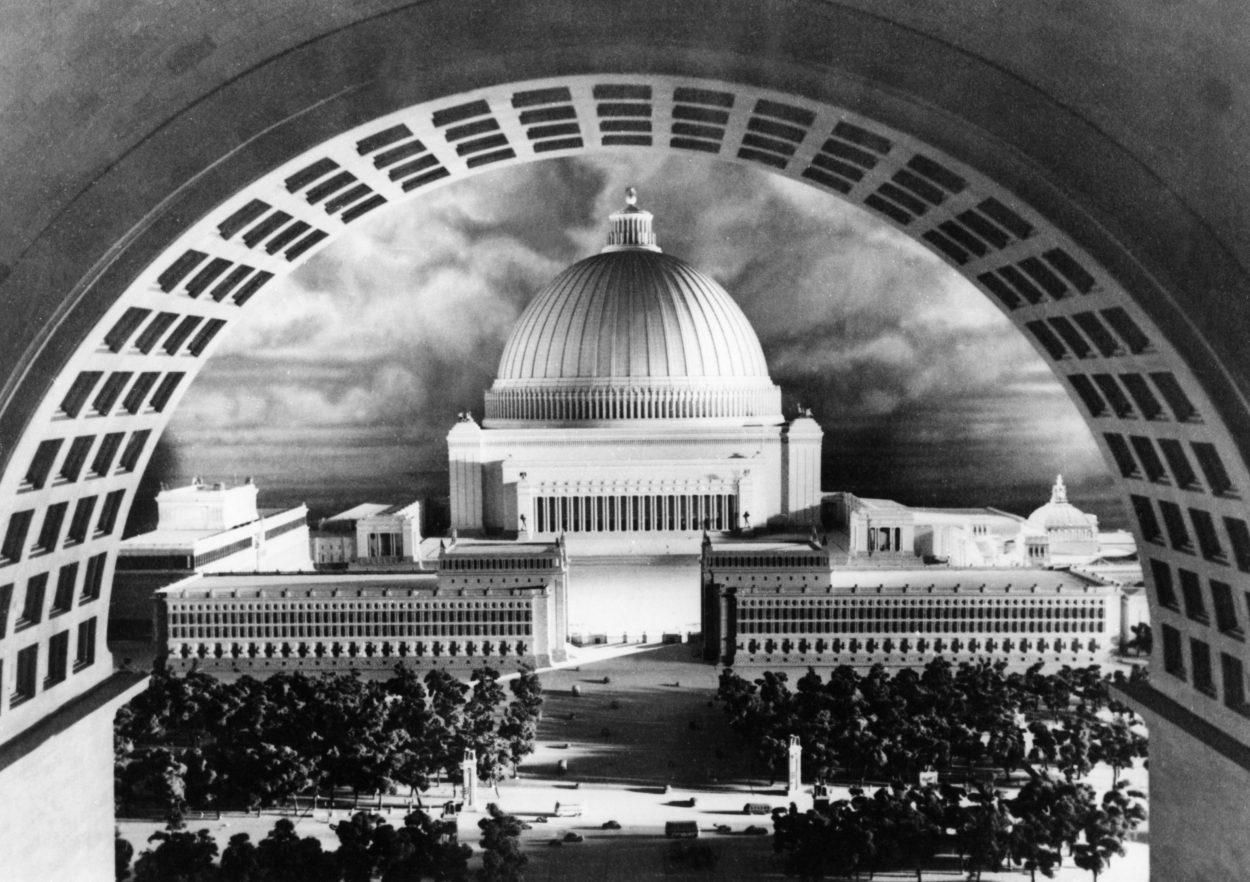

Figure 6: The Volkshalle Germania

Figure 7: Fendi Fashion Relocates to the Palazzo della Civilta Italiana in Rome

Figure 5: The Volkshalle’s Great Dome can be seen at the top of this model of Hitler’s plan for Berlin

Figure 6: The Volkshalle Germania

Figure 7: Fendi Fashion Relocates to the Palazzo della Civilta Italiana in Rome

Chapter Two

Chapter Two is focused on the case studies in Italy and Germany, specifically Rome and Berlin. Two architectural buildings that demonstrated fascism were: Palazzo della Civilta Italiana, Rome and The Volkshalle, Berlin. I previously discussed how fascism was through two political leaders, and a relationship between the two led them to visibly show this language through architectural buildings. This chapter will examine how these buildings were: constructed, used and viewed.

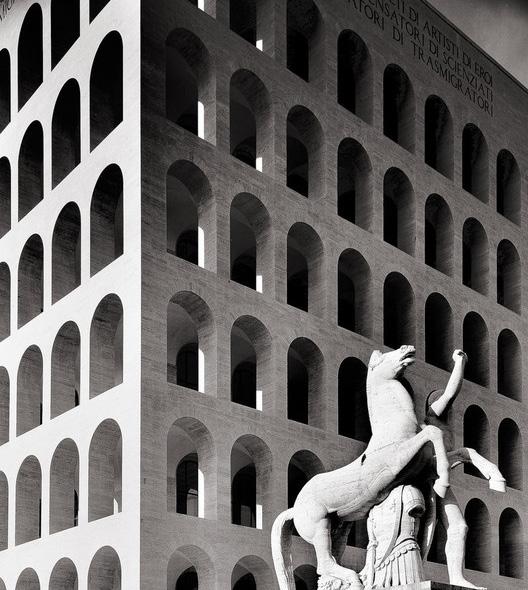

Benito Mussolini used architectural buildings to successfully carry out propaganda acts against his country, to reflect his power. This began with his interest in Rome while getting ready for the 1942 World’s Fair in the late 1930s (Kessler, 2015). He was involved in the development of a brand-new neighbourhood in Rome that celebrated the country’s restored imperial grandeur. The eye-catching Palazzo della Civilita Italiana was described as a “sleek, rectangular marvel with a facade of abstract arches and rows of neoclassical statues lining its base” (Carter, 2020, p.379). Although the fair was postponed due to World War Two, the structure is still standing and has an engraving on its exterior that quotes Mussolini referring to the Italian people as “people of poets, artists, heroes, saints, thinkers, scientists, navigators, and transmigrants” (Carter, 2020, p.380), in his speech announcing the invasion of Ethiopia in 1935. Mussolini attempted to manipulate his people by referring to them as “artists, heroes, saints” in order to win their respect. As a result of Mussolini’s abuse attempt, the Palazzo della Civilta Italiana was a “relic of abhorrent fascist aggression, however, it was glorified in Italy and celebrated as their modernist icon” (Carter, 2020, p.380). Therefore, Mussolini achieved his aim as fascism was embedded into his ‘icon’ building reflecting power, which serves as a form of propaganda for the regime.

“These buildings of ours should not be conceived for the year 1940, no, not for the year 2000, but like the cathedrals of our past they shall stretch into millennia of the future”

Hitler, speech at Nuremberg Party Congress, 1937 (Ladd, 1997, p.126)

Similarly, Adolf Hitler used his power to change the architectural landscape as a political weapon to impress the world, to achieve a “timeless static city” (Ladd, 1997, p.140). Just like Mussolini, he was motivated by Ancient structures, as they established a level of quality and rigour that shapes perceptions of what constitutes worthy architecture. In Germany, these were typically domed concrete structures, which is visually seen in The Volkshalle designed by Albert Speer for Hitler (Jones, 2003). The purpose of this building was to allow him to present speeches to the locals at the heart of Germania’s plan (Lamothe, 2021). He wanted to “stretch into millennia of the future” (Ladd, 1997, p.126), which meant he desired to alter society by changing the landscape with new ideas for a ‘new berlin’. Overall, Hitler met his goals to some extent, as The Volkshalle exceeded his expectations in terms of height, scale, and capacity, but it was never constructed because the Third Reich missed its target by 998 years (Glancey, 2017).

2.1.1 Construction?

Ancient Rome and Greece in antiquity were the models for European architecture, also known as the classical period (Jones, 2003). This was portrayed in both Mussolini’s and Hitler’s styles of architecture. According to Mussolini, he signified fascism as a

“house of glass” (Scobie, 1990, p.12), by using a mixture of glass and concrete, which allowed transparency of the fascist idea. The main aim of fascism was to control the lives of people and using ‘glass’ was a way of deflecting their true intentions. Using specific materials such as ‘glass’ allowed Mussolini to deceive the people in Italy to show they were not hiding anything, in that glass would have enabled people to have an insight into the ongoings. The architects Guerrini, La Padula and Romano wanted the Palazzo della Civilta Italiana to showcase “modern yet there are classical elements and ideologies embedded into the architecture” (Kessler, 2015, p.4). ). This is visible on the exterior of the building, which was built from reinforced concrete joined by parallel portal frames with mythical Greek sculptures on each end, as shown in figure 7. (Ceccoli, et al., 2011). Sculptures are significant as they are depicted as gods, powerful and immortal heros, reflecting how Mussolini desired to be portrayed.

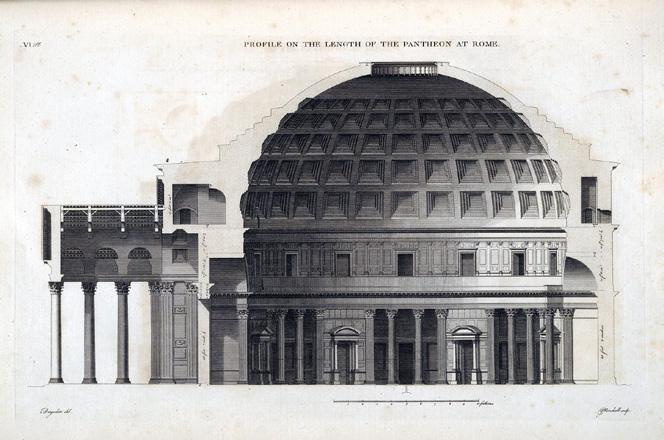

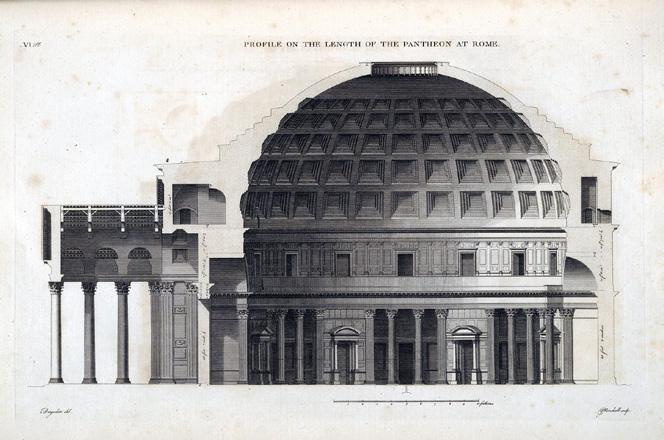

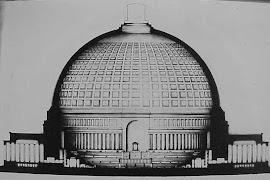

Whereas, The Volkshalle was never constructed due to World War Two. The construction would have been to an immense scale rising at 954ft and capped dome at 825ft in diameter, with the ability to hold over 150,000 people (Ladd, 1997). Hitler was drawn to Rome’s political power given the scale of the governmental structures that were symbolised and represented as references for his projects in order to exemplify them in his own work (Seraphim, 2013). An example of this is The Pantheon Rome, Hitler manipulated this as evidenced in figures 8 and 9. In a linear perspective from the arch The Volkshalle is visible, done to have control and ability to direct the viewers’ focus, as seen in figure 6, (Johnson, N.D). As a result of this, it supported Hitler’s propaganda aim as it gave him strength and power in the National Socialist government.

Figure 8: The Pantheon Rome

Figure 9: Speer, Albert. Berlin: Volk Hall Interior Elevation Pantheon

2.1 Case study: Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana and The Volkshalle

Figure 8: The Pantheon Rome

Figure 9: Speer, Albert. Berlin: Volk Hall Interior Elevation Pantheon

2.1 Case study: Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana and The Volkshalle

2.1.2 Use?

Both leaders used these architectural buildings in a way to portray their power and gain rule of their people. In Berlin, Hitler had the intention of using The Volkshalle, as a way of gathering people and presenting speeches about his political regime, as his sense of power depended on the capacity of crowds. The Volkshalle aimed to hold 150,000 people, which would have met Hitler’s aim. As the building was not constructed, he alternatively attempted this through other architectural spaces such as Zeppelin Field, shown in figure 10, where he hosted party congresses (Ladd, 1997). The Cathedral of Light reflected religious symbols, as beam lights shot up into the night sky, showcasing the rally in a spiritual way (Hagen and Ostergren, 2019). The white beams reflect purity, which can elicit false religious connotations in an attempt to deceive the audience, which was his propaganda achievement. Speer’s design made Hitler the centre of attention, casting a shadow over him to appear godlike.

The relationship with Italy is similar, as the Palazzo della Civilta Italiana was intended to be the focal point of the 1942 World Fair in Rome. In order to illustrate the ancient past and to reflect Mussolini’s primary interest (Kessler, 2015). However, due to the Second World War, this did not occur, and the building was eventually leased to the fashion brand Fendi, which had the ability to strip all political associations and take over the heritage site (Malone, 2017). This allows the building to uphold its past while taking on a new identity as it still preserves existing structures (Kessler, 2015), such as statues and a quote from Mussolini embellished on the structure referring back to his people. Arguably, coexistence demonstrates the significance of the present concerning political association while allowing the glorification of the past. In Italy, there was far less demolition which allowed a public memory of fascism which was an opportunity to go back and review the past (Malone, 2017). Therefore, this allowed an imprint of fascism throughout history through visible traces left in the landscape.

2.1.3 Perception?

People had various opinions on these architectural buildings, due to the marks it left on people and the city. According to Sean Maantesso, “everywhere you look in Italy, you are confronted by history, Roman Amphitheatres sit alongside renaissance cathedrals, medieval castles dot the countryside” (Carter, 2020, p.377). What remained in Italy was a key part in repressing memory till this day, as it was seen in urban projects, monuments, plaques, schools and street names (Malone, 2017). Similarly, Hitler intended to leave “a lasting mark on the history of human achievement” (Smith, 2021, p.2). He accomplished this as design “structures are constant reminders of the regimes presences towering over the people” (Kessler, 2015, p.24), shown in the Zepplin Field as it was at an immense scale and shows symmetry. Thereby, both leaders achieved their aims to mark traces of their political regimes on their country’s architectural forms, in an attempt to gain more recognition and power. Although they both attempted similar acts, the regime lingered for longer in Italy’s landscape as the majority of the buildings were reused, whereas in Germany the buildings were destroyed either by war or choice (Malone, 2017).

To conclude, this chapter establishes that Mussolini and Hitler were influenced by ideology, allowing them to carry out their propaganda. They both desired to dominate their country in order for the regime to seize power, which would have presented them as gods. However, World War Two prevented the March on Rome and The Volkshalle, also known as the ‘Unbuilt Nazi Pantheon,’ from being built, allowing them to find alternative ways to showcase their propaganda. Over time both leaders faced significant criticism, which could not be erased once the regimes ended, demonstrating the impact fascism had on the landscape and people.

Figure 10: The Cathedral of Light above the Zeppelintribune, 1936

Chapter Three: Demolish, Preserve and Reuse

V.

Chapter Three

Chapter three will evaluate how post-fascism rehabilitated perceptions of certain buildings. Specifically, Hannah Malone’s theory was used to evaluate fascist structures, which was aided by three options: “destroy, reuse, or neglect.” Both countries opted for different outcomes when it came to how they treated their buildings. Italy gravitated more towards preserving and reusing buildings, whereas Germany determined to demolish more. In order to evaluate the impact this had on both architectural landscapes, buildings from each country will be compared and contrasted through each choice of ‘destroy, reuse or neglect’.

3.1 Attitudes Post-fascism

The primary argument is that the methods used to maintain, change, or demolish structures after fascism fell are similar to those used to choose, alter, and delete public memories (Malone, 2017). This was evident when comparing how Italy and Germany dealt with fascist buildings designed by architects for their political leaders, which reflected their ideological aims. This was achieved in Italy, as more were reused and preserved, whereas, Germany demolished more given that National Socialism was far worse, and that it also affected Italy (Malone, 2017). This demonstrates that both Mussolini and Hitler succeeded with their propaganda acts, as this left a long-term print on not only the city but the people. This is supported by Brian, who stated, “Berlin is a haunted city. People living in Berlin could look back on a host of troubles: the last ruler of an ancient dynasty driven to abdication that ruled by terror; that terror unleashed on the rest of Europe, bringing retribution in the form of devastation, defeat and division. Now that division and the regime that ruled east Berlin are also memories. Memories are a potent force; the Berliners would like to forget but they hear far too much about Hitler and vanished Jews” (Ladd, 1997, p.12). This establishes, that fascism had a substantial effect on Berliners to the point that they perceived their city as ‘haunted’, which determined the destruction of countless fascist buildings as they symbolised Hitler and his regime. Whereas, Italy was not as bad which allowed fascist buildings to stay standing.

3.2 Demolition

3.2.1

Littoriale, Rome

Fascist ornamentation was integrated into the framework of buildings and was hard to remove (figure 13). This meant destroying buildings in Italy was seen as a ‘spontaneous attack’ (Malone, 2017, p.449), after the regime change and was not often done. Many buildings were neglected instead of being destroyed, which meant only the most fascist symbols such as images and portraits of the Duce were destroyed. As demonstrated in figure 11, a bronze statue of Mussolini on a horseback was ‘decapitated on July 26, 1943, in a sort of ceremonial murder’ at the Littoriale, Rome (now Renato Dall’Ara) stadium in Bologna. To remove it from history, in 1947, the statue was melted down in a symbolic act of ‘recycling’, and new casts of it served as memorials to slain partisans (Malone, 2017). This clearly shows that Mussolini’s body was marked as fascist, as it displayed his past dictatorship, which needed to be eliminated from the landscape. Although the Italians were not as successful in destroying fascist relics, the removal of Mussolini’s sculpture shows how the regime’s importance was diminished once he was seized, as it symbolised his propaganda. They opted to reuse or neglect buildings, given the fact that the Roman style was already established.

3.2.2 Ehrentempel, Munich

Similarly, Germany had the choice to demolish, reuse, or let buildings fall into disrepair. In the late 1980s, they shifted more towards destruction and isolation. The majority of the destruction was a result of bombing or post-war action which further demolished buildings. They supported ‘critical preservation’, which is accompanied by instructional materials aimed at contextualising and changing sites (Malone, 2017). For instance, the Ehrentempel in Munich were a pair of neoclassical ‘temples of honour’, constructed in 1935 in memory of sixteen men who died in the unsuccessful Munich Putsch in 1923, also known as the first National Socialist attempt to seize power (Anon, n.d.). Hitler felt it was necessary to honour them, therefore their deaths were used as propaganda for the Nazi’s. The word Tempel denoted that these political spaces should be kept sacred. The temple resembled a modernised mix of GrecoRoman architecture, because of its unornamented appearance (Smith, 2021.). The use of stone and columns provided stability to the design concept, which successfully reflected Hitler’s interest in ancient structures. Due to its tie to fascism, it got destroyed in 1947 as part of denazification (György, 2009). This demonstrates that Germany was far more affected by fascism as it leaned more toward demolition in an attempt to diminish the regime, whereas Italy ‘spontaneously’ destroyed significant statues like Mussolini’s that reflected his dictatorship.

Figure 11: Renato Dall’Ara Stadium

Figure 12: Ehrentempel

3.3 Preserve

3.3.1 The Art of Ventennio, Rome Destruction was limited in Italy, as an alternative, many high-profile monuments were preserved, mainly as they were on economic, political, aesthetic or heritage grounds (Malone, 2017). The remains of the fascist period provide an insight into Italian thoughts of the past, which was perceived as a ‘difficult heritage’ as locals were not able to shake free from it. On the other hand, it may be argued that preservation, which keeps memories of the past, is more ideal than demolition for the development of democratic values (Malone, 2017). This was achieved through ‘uncritical preservation’, which allowed for sites to merge into the urban landscape without contextualisation, which is one reason why fascist buildings in Italy are still surviving. The Italian landscape is dominated by the Ventennio, which also holds a dark place in the country’s public memory. This is visible in the form of urban projects such as monuments, plaques, and street names, the Ventennio left permanent marks on Italy’s cityscape which are still visible to this day. An example of this is Stadio de’ Marmi (Stadium of the Marbles), which was preserved, shown in figure 14 (Malone, 2017). Classical marble statues of athletes surrounded the stadium, reflecting youth and stone material exemplifying the Roman spirit. The preservation of Ventennio’s art could also be a sign of receptivity to the past and an ability to reconcile fascist contradictions. This alludes to the fact that preservation allowed fascism to keep its significance after the regime shown in the architectural landscape. This indicates that, contrary to the locals’ perception of fascism as a “difficult heritage,” Italy was far less disturbed. An alternative response would have been to ignore the site, but it is still used by athletes and will therefore remain standing.

Figure 14: Stadio de’ Marmi in the Foro Mussolini, now Italico, in Rome

Figure 13: Bas-relief representing Mussolini on horseback on the exterior of the Palazzo degli Uffici in Rome

Figure 14: Stadio de’ Marmi in the Foro Mussolini, now Italico, in Rome

Figure 13: Bas-relief representing Mussolini on horseback on the exterior of the Palazzo degli Uffici in Rome

Figure 16:

3.3.2

Topography of Terror, Berlin

Contrarily, Germany had many more structures fall during World War Two, as well as further demolitions that occurred after. In the 1980s, many building outlines were preserved and used as exhibits for educational purposes, figure 15 is an example of this that allowed people to express their own opinions on fascism (Malone, 2017), in attempt to separate the current from the past, this was quickly criticised by the public (Ladd, 1997). This was easily achieved, as Germany embraced ‘critical preservation’, which is supplemented by educational material, that is accompanied by educational content intended to contextualise, modify, and “desacralize” sites (Malone, 2017, p.452). A prominent example of this is the Topography of Terror, Berlin, designed by Peter Zumthor as an exhibition with the goal of educating the public, about the crimes committed under National Socialism and preventing the past from being forgotten (Leoni, 2014). The site was previously used by the Nazi institution; therefore, it is used to unveil the story of post-war Germany, which was preserved as an ‘open wound’ reflecting the history (Leoni, 2014). Zumthor wanted to portray this “… exhibition in the usual sense…should not take place on this even and levelled earth. What happened here, what has come down to us, should be experienced. It should be pointed to clearly, objectively, but not blotted out by commentary, architecture or didactic mise-en-scène. The feeling for the reality of this site of perpetrators and victims must remain” (Leoni, 2014, p.116). Shown in figure 17 through a model of the design’s intentions. The installation’s towering and tight shape, as seen in figure 16, uncovers a long black space with similar features to a box, which can correspond to the horror the Berliners felt under the regime as if they were trapped, demonstrating the effects of fascism and the significance of the site.

Figure 15: The site, wiped clean, in 1952

Site plan of Peter Zumthor’s project for the Topography of Terror

Figure 17: Visualisation of the interior showing how the site would have disappeared from view behind a diminishing perspective of vertical uprights

Figure 15: The site, wiped clean, in 1952

Site plan of Peter Zumthor’s project for the Topography of Terror

Figure 17: Visualisation of the interior showing how the site would have disappeared from view behind a diminishing perspective of vertical uprights

3.4 Reuse

3.4.1

Palazzo della Civilta Italiana, Rome

The most common response for Italy post-fascism was to reuse or recycle buildings of the regime. This was achieved by, renaming monuments, street names and piazzas or designer brands overtaking the buildings to reuse the fascist sites without the lingering memories (Ladd, 1997). This indicates, that there was an attempt to remove physical remains of fascism from the landscape, in hopes that it altered the meaning of the place.

The Palazzo della Civilta Italiana, structure was thought to be a complex monument constructed for the E42, which was intended to commemorate the anniversary of the fascist rule in 1942 (Malone, 2017). Due to its participation in Mussolini’s propaganda campaign, it held fascist connotations, which was reflected in the architecture through the preservation of sculptures. Alberto de Felci (figure 20) one of the mythical Greek heroes, was placed near the building’s entrance, symbolising power and strength, revealing its value to Mussolini. Eventually, the fashion company Fendi overtook the building in an attempt to distance itself from fascism. Pietro Beccari, the executive in charge, rejected the criticism, saying that “this building is beyond a discussion of politics. It is aesthetics. It is a masterpiece of architecture…for Italians and Romans, it is completely deloaded, empty of any significance…we never saw it through the lens of fascism” (Malone, 2017, p.457). Consequently, this demonstrates that Mussolini’s propaganda aim met the criteria of the building, which could still be viewed even after it had been taken over by a fashion business. Thereby, it continues to have significance even after the political regime is gone.

3.4.2 Detlev-Rohwedder-Haus, Berlin Germany lent more towards demolition, but since the 1980s, structures have been preserved (Malone, 2017). A case study that portrays this is Detlev-Rohwedder-Haus (Aviation Ministry), seen in figure 18, which was the first major government building to be completed by the National Socialist regime. Due to this, towards the end of the regime’s rule, it was set aside for demolition; however, in August 1999, it was repurposed as the Finance Ministry (Philpotts, 2012). This was done in an attempt to eliminate fascist connections; however, a local reported that the structure was “like a book” (Philpotts, 2012, p.208), where different chapters of Germany’s history from the twentieth century could be read. This establishes that recycling the structure with the aim of reusing was successful to an extent. The reason for this is that fascism is embedded in the building’s

This chapter demonstrated how both countries dealt with fascist structures after the regime was over and examines the reasoning behind their choices. Given their leaders’ legacies, each country approached the architectural structures differently. Berlin was known to be a ‘haunted city’ because Hitler aimed to rehabilitate the landscape to make it like ancient Rome, which was difficult to achieve, leading more to be demolished, unlike Italy, which preserved and reused more. Overall, this asserts that even when a political system is abolished, structures retain their significance in society even though the traumatic ones were destroyed.

history, which reflects the regime, as a result, even after the building is reused, fascism will continue to be associated with it.

Figure 20: Mythical Greek hero Alberto de Felci at The Palazzo della Civilta Italiana

Figure 18: The building of the Reichsluftfahrtministerium in the Wilhelmstrabe, December, 1938

Figure 19: The Palazzo della Civilta Italiana

history, which reflects the regime, as a result, even after the building is reused, fascism will continue to be associated with it.

Figure 20: Mythical Greek hero Alberto de Felci at The Palazzo della Civilta Italiana

Figure 18: The building of the Reichsluftfahrtministerium in the Wilhelmstrabe, December, 1938

Figure 19: The Palazzo della Civilta Italiana

VI. Conclusion

Conclusion

This dissertation has shown that Mussolini and Hitler were key figures in the rise of fascism in the twentieth century. They both used architectural structures to promote the idea of a strong centralised government. Fascism emerged in both Italy and Germany following the Great War, which left people in need of a leader to take over their nation. This allowed both leaders the opportunity to strengthen their political systems and pursue their ideologies through propaganda. Obtaining more power and recognition was the main goal, which was conveyed through newsreels, newspapers, and magazines showing their architectural concepts. Rome was entred around a historic empire, whereas However, Germany had to claim Greco-Roman architecture in order to restore its power and culture. This form of architecture gave Germany a sense of power and individuality, which motivated Hitler to carry out his acts. Both leaders achieved propaganda through architectural designs such as The Palazzo della Civilta Italiana, Rome and The Volkshalle, Berlin. The Palazzo della Civilta Italiana was an established building that seized Mussolini’s attention, as the neighbourhood restored the imperial grandeur that drove his propaganda acts; however, this was different for Hitler as The Volkshalle was never constructed due to World War Two.

Hannah Malone’s theory of ‘destroy, reuse and neglect’ was justified through varies architectural examples. It clearly demonstrated that each country approached fascist buildings differently, in an attempt to remove its connotations revealing that some still held their importance in society after the political regime was lost due to the impact their leaders had. Italy opted more towards reuse and preservation, whereas, Germany destroyed and neglected more, which shows that fascism affected Germany more than Italy. This is primarily because fascism caused Berlin to be regarded as a “haunted city” as a result of Hitler’s actions.

Therefore, ideology had a significant role in driving Italy and Germany in the direction that permitted them to be seen as siblings. Mussolini’s ideology emphasised the importance of undermining individual rights. He believed that a totalitarian state would unite Italy, similarly, Hitler believed that a totalitarian state would allow him complete control over the peoples’ lives. Both countries were influenced by Roman architecture, which was evident in both their designs. This left traces of fascism on the landscapes that were difficult to remove once the regime lost its significance. Overall, fascism was successful to an extent, as the regimes’ aggression resulted in the outbreak of World War Two.

VII. Bibliography

Anon, (n.d.). Traces of Evil. (Online) Available at: https://www.tracesofevil.co,/search/label/Ehrentempel.

Alexander, J. (2004). Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany: the ’fascist’ style of rule. London: Routledge.

Arthurs, J. (2013). Excavating modernity: the Roman past in fascist Italy. Ithaca, N.Y. London: Cornell University Press.

Carter, N. (2020). “What Shall We Do With It Now?”: The Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana and the Difficult Heritage of Fascism. Australian Journal of Politics & History, 66(3), pp.377-395.

Ceccoli, C., Trombetti, T. and Biondi, D. (2011). Structural evaluation of the Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana in Rome. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering, 7(1-2), pp.147-162.

Eatwell, R. (2011). Fascism. Random House.

Focardi, F. ed. (2022). Rethinking Fascism: The Italian and German Dictatorships (Vol. 4). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

Glancey, J. (2017.) The Unbuilt Nazi Pantheon: Unpacking Albert Speer’s “Volkshalle”. Available at: https://www.archdaily. com/806680/unbuilt-nazi-pantheon-unpacking-albert-speer-volkshalle-germania-jonathan-glancey (Accessed: 17th December 2022)

György P. (2009). Spirit of the place from Mauthausen to Moma. New York: Central European University Press.

Hagen, J. and Ostergren, R.C. (2019). Building Nazi Germany: Place, space, architecture, and ideology. Rowman & Littlefield.

Jones, M.W. (2003). Principles of Roman architecture. Yale University Press.

Johnson, L.W. (N.D). Propaganda and Ideology: The Architecture of the Third Reich. University of North Carolina.

Kessler, H.A. (2015). The Palazzo Della Civilta Italiana: From Fascism to Fendi. Ohio University.

Lane, B.M. (1968). Architecture and Politics in Germany: 1918-1945.

Ladd, B. (1997). Ghosts of Berlin: Confronting German History in the Urban Landscape. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lasansky, D.M. (2004). The Renaissance perfected: architecture, spectacle, and tourism in fascist Italy (Vol. 4). Penn State Press.

Lamothe, S. (2021). Principles of Nationalist Architecture. Alberta Canada: University of Calgary

Leoni, C. (2014). Peter Zumthor’s ‘Topography of Terror’. Arq: Architectural Research Quarterly, 18(2), pp.110-122.

Lee, S.J.(2016). European Dictatorships 1918-1945. Routledge.

Lyttelton, A. (2004). The seizure of power: fascism in Italy, 1919-1929. Routledge.

Malone, H. (2017). ‘Legacies of Fascism: Architecture, heritage and memory in contemporary Italy’, Modern Italy, 22(4), 445-470

Nicoloso, P. (2022). Mussolini, Architect: Propaganda and Urban Landscape in Fascist Italy. University of Toronto Press.

Philpotts, M. (2012). Cultural-Political Palimpsests: The Reich Aviation Ministry and the Multiple Temporalities of Dictatorship. New German Critique, 39(3), pp.207–230.

Smith, M.L. (2021). Germania: The Nazi Party and the Third Reich through the Lens of Classical Architecture. University of Mississippi

Scott, K. (1932). “Mussolini and the Roman Empire”. The Classical Journal, 27(9), pp.645-657.

Seraphim, A.P. (2013). Berlin: Urban Development. Academia

Scobie, A. (1990). Hitler’s state architecture: the impact of classical antiquity (Vol. 45). Penn State Press.

Tikkanen, A. (2022). March on Rome. (Online) Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/March-on-Rome (Accessed: 17th December 2022)

Bibliography

VIII. List

of Figures

List of Figures

Figure 1: Gunderman, R. (2019) Both Mussolini’s and Hitler’s rise to power. Available at: https://theconversation.com/after-100years-mussolinis-fascist-party-is-a-reminder-of-the-fragility-of-freedom-110015 (Accessed: 10th November 2022)

Figure 2: Anon, (2022) Celebration of the 10th anniversary of the “March on Rome”, October 28, 1932. Available at: https://akgimages.prezly.com/march-on-rome-100-years (Accessed: 10th November 2022)

Figure 3: Glancey, J. (2017) The Unbuilt Nazi Pantheon: Albert Speer’s “Volkshalle”. Available at: https://www.archdaily. com/806680/unbuilt-nazi-pantheon-unpacking-albert-speer-volkshalle-germania-jonathan-glancey (Accessed: 10th November 2022)

Figure 4: Greco-Roman Architecture. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greco-Roman_world (Accessed: 11th November 2022)

Figure 5: The Volkshalle’s Great Dome can be seen at the top of this model of Hitler’s plan for Berlin. Available at: https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volkshalle (Accessed: 10th November 2022)

Figure 6: Milligan, M. (2022) The Volkshalle Germania. Available at: https://www.heritagedaily.com/2022/02/germania-hitlersmegacity/142687 (Accessed: 10th November 2022)

Figure 7: Archdaily (2015) Fendi Fashion Relocates to the Palazzo della Civilta Italiana in Rome. Available at: https://www.archdaily. com/776091/fendi-fashion-house-relocates-to-the-palazzo-della-civilta-italiana-in-rome (Accessed: 11th November 2022)

Figure 8: Ranogajec, P. A. (2015) The Pantheon Rome. Available at: https://smarthistory.org/the-pantheon/ (Accessed: 15th November 2022)

Figure 9: Boehlert, A. M. (2017) Speer, Albert. Berlin: Volk Hall Interior Elevation Pantheon. Available at: https://www. semanticscholar.org/paper/Hitler’s-Germania%3A-Propaganda-Writ-in-Stone-Boehlert/305e9fcf51f30d7625840b8f2d7d1bb7f48 e7d3e (Accessed: 15th November 2022)

Figure 10: The Cathedral of Light above the Zeppelintribune, 1936. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cathedral_of_ Light (Accessed: 15th November 2022)

Figure 11: Renato Dall’Ara Stadium. Available at:http://www.centrostudipierpaolopasolinicasarsa.it/approfondimenti/25290/ (Accessed: 15th November 2022)

Figure 12: Ehrentempel. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ehrentempel (Accessed: 15th November 2022)

Figure 13: Malone, H. (2017) Bas-relief representing Mussolini on horseback on the exterior of the Palazzo degli Uffici in Rome. Modern Italy, 22(4), 445-470

Figure 14: Malone, H. (2017) Stadio de’ Marmi in the Foro Mussolini, now Italico, in Rome. Modern Italy, 22(4), 445-470

Figure 15: Leoni, C. (2014) The site, wiped clean, in 1952. Arq: Architectural Research Quarterly, 18(2), pp.110-122.

Figure 16: Leoni, C. (2014) Site plan of Peter Zumthor’s project for the Topography of Terror. Arq: Architectural Research Quarterly, 18(2), pp.110-122.

Figure 17: Leoni, C. (2014) Visualisation of the interior showing how the site would have disappeared from view behind a diminishing perspective of vertical uprights. Arq: Architectural Research Quarterly, 18(2), pp.110-122.

Figure 18: The building of the Reichsluftfahrtministerium in the Wilhelmstrabe, December, 1938. Available at: https://www. liberationroute.com/pois/853/detlev-rohwedder-haus (Accessed: 28th January 2022)

Figure 19: Palazzo della Civilta Italiana. Available at: https://www.culturalheritageonline.com/location-163_Palazzo-dellaCivilt%C3%A0-Italiana---Civilt%C3%A0-del-Lavoro.php (Accessed: 28th November 2022)

Figure 20: Mythical Greek hero Alberto de Felci at The Palazzo della Civilta Italiana. Available at: https://www.culturalheritageonline. com/location-163_Palazzo-della-Civilt%C3%A0-Italiana---Civilt%C3%A0-del-Lavoro.php (Accessed:28th Novemeber 2022)

Power, Politics and Space: Fascist Architecture in Italy and Germany

Figure 1: Both Mussolini’s and Hitler’s rise to power

Figure 2: Celebration of the 10th anniversary of the “March on Rome”, October 28, 1932

Figure 1: Both Mussolini’s and Hitler’s rise to power

Figure 2: Celebration of the 10th anniversary of the “March on Rome”, October 28, 1932

Figure 3: The Unbuilt Nazi Pantheon: Albert Speer’s “Volkshalle”

Figure 4: Greco-Roman Architecture

Figure 3: The Unbuilt Nazi Pantheon: Albert Speer’s “Volkshalle”

Figure 4: Greco-Roman Architecture

Figure 5: The Volkshalle’s Great Dome can be seen at the top of this model of Hitler’s plan for Berlin

Figure 6: The Volkshalle Germania

Figure 7: Fendi Fashion Relocates to the Palazzo della Civilta Italiana in Rome

Figure 5: The Volkshalle’s Great Dome can be seen at the top of this model of Hitler’s plan for Berlin

Figure 6: The Volkshalle Germania

Figure 7: Fendi Fashion Relocates to the Palazzo della Civilta Italiana in Rome

Figure 8: The Pantheon Rome

Figure 9: Speer, Albert. Berlin: Volk Hall Interior Elevation Pantheon

2.1 Case study: Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana and The Volkshalle

Figure 8: The Pantheon Rome

Figure 9: Speer, Albert. Berlin: Volk Hall Interior Elevation Pantheon

2.1 Case study: Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana and The Volkshalle

Figure 14: Stadio de’ Marmi in the Foro Mussolini, now Italico, in Rome

Figure 13: Bas-relief representing Mussolini on horseback on the exterior of the Palazzo degli Uffici in Rome

Figure 14: Stadio de’ Marmi in the Foro Mussolini, now Italico, in Rome

Figure 13: Bas-relief representing Mussolini on horseback on the exterior of the Palazzo degli Uffici in Rome

Figure 15: The site, wiped clean, in 1952

Site plan of Peter Zumthor’s project for the Topography of Terror

Figure 17: Visualisation of the interior showing how the site would have disappeared from view behind a diminishing perspective of vertical uprights

Figure 15: The site, wiped clean, in 1952

Site plan of Peter Zumthor’s project for the Topography of Terror

Figure 17: Visualisation of the interior showing how the site would have disappeared from view behind a diminishing perspective of vertical uprights

history, which reflects the regime, as a result, even after the building is reused, fascism will continue to be associated with it.

Figure 20: Mythical Greek hero Alberto de Felci at The Palazzo della Civilta Italiana

Figure 18: The building of the Reichsluftfahrtministerium in the Wilhelmstrabe, December, 1938

Figure 19: The Palazzo della Civilta Italiana

history, which reflects the regime, as a result, even after the building is reused, fascism will continue to be associated with it.

Figure 20: Mythical Greek hero Alberto de Felci at The Palazzo della Civilta Italiana

Figure 18: The building of the Reichsluftfahrtministerium in the Wilhelmstrabe, December, 1938

Figure 19: The Palazzo della Civilta Italiana