Zoning and the “Sorting Hat” Page 4 Harvesting the Sun on Maryland Farmland Page 18 Peculiar Problems with Variance Ordinances Page 24 LAND USE Volume LI • Number 5 November/December 2018

18

Published bimonthly by the Maryland State Bar Association, Inc.

520 W. Fayette St. Baltimore, Maryland 21201

Telephone: (410) 685-7878 (800) 492-1964

Website: www.msba.org

Executive Director: Victor L. Velazquez

Editor: W. Patrick Tandy

Assistant to the Editor: Lisa Muscara

Advertising Sales: MCI | USA

Subscriptions: MSBA members receive THE MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL as $20 of their dues payment goes to publication. Others, $42 per year.

POSTMASTER: Send address change to THE MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL

520 W. Fayette St. Baltimore, MD 21201

The Maryland Bar Journal welcomes articles on topics of interest to Maryland attorneys. All manuscripts must be original work, submitted for approval by the Special Committee on Editorial Advisory, and must conform to the Journal style guidelines, which are available from the MSBA headquarters. The Special Committee reserves the right to reject any manuscript submitted for publication.

Advertising: Advertising rates will be furnished upon request. All advertising is subject to approval by the Editorial Advisory Board.

Editorial Advisory Board

Hon. Vicki Ballou-Watts, Chair

Richard Adams

Robert Anbinder

Alexa Bertinelli

Cameron Brown

Susan Francis

Peter Heinlein

Hon. Marcella Holland

Louise Lock

Victoria Pepper

Corinne Pouliquen

Sahmra Stevenson

Gwendolyn Tate

MSBA Officers (2018-2019)

President: Hon. Keith R. Truffer

President-Elect: Dana O. Williams

Secretary: Deborah L. Potter

Treasurer: Hon. Mark F. Scurti

Statements or opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Maryland State Bar Association, its officers, Board of Governors, the Editorial Board or staff. Publishing an advertisement does not imply endorsement of any product or service offered.

29

24

Land Use Features

4 Zoning and the “Sorting Hat”: Why We Curse Special Exceptions

By Peter Z. Goldsmith and Megan M. Roberts-Satinsky

10 A Possible Avenue to Reach Judicial Review of a “Garden Variety” Administrative Decision Through Alleging Common Law Taxpayer Standing

By Timothy Dugan

14 Takings in Time: Legal Challenges to Land UseMoratoria

Under the Fifth Amendment and Fair Housing Act

By Thomas G. Coale

By Thomas G. Coale

18 Harvesting the Sun on Maryland Farmland: Local Zoning Restrictions for Solar Fields

By Casey L. Cirner

By Casey L. Cirner

24 Peculiar Problems with Variance Ordinances

By Derek M. Van De Walle

29 “Quiet Revolution”: Maryland Slowly Takes Back Local Government Land Use Controls

By Joseph A. Stevens

By Joseph A. Stevens

Departments

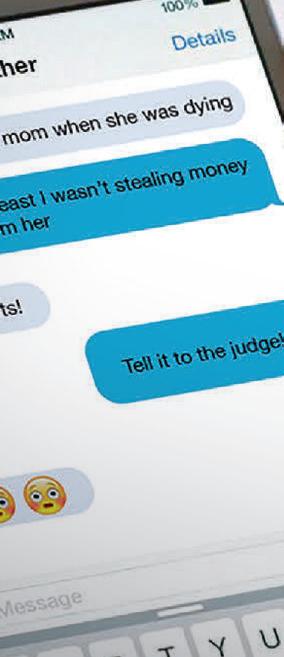

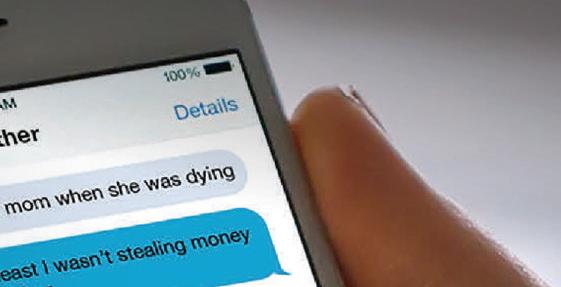

34 Committee on Ethics

Ethics Docket No. 2018-06

An attorney’s obligations under the Maryland Rules of Professional Conduct to avoid conflicts of interest between current and former clients in light of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

November 2018 3 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL

14

Volume LI • Number 5 November/December 2018

Zoning and the “Sorting Hat” Why We Curse Special Exceptions

By Peter Z. Goldsmith and Megan M. Roberts-Satinsky

“[A] special exception, while not exactly twice removed from what is permissible, as the term implies, is nevertheless a conditional allowance.” Costco Wholesale Corp. v. Montgomery Cnty., No. 2450, Sept. Term, 2015, 2018 WL 1747920, at *1 (Md. Ct. Spec. App. Apr. 11, 2018).

Every so often, a local newspaper will publish a headline along the lines of: DEVELOPER AWARDED SPECIAL ZONING EXCEPTION TO DEVELOP COMMERCIAL PROPERTY IN RESIDENTIAL DISTRICT. The headline reflects the misunderstanding that a special exception is an exception to a zoning code or, perhaps, tantamount to a rezoning. See John J. Delaney et al., Handling the Land Use Case 19 (3d ed. 2012) (“The decision to grant or deny a special exception, unlike the decision in a zoning case, does not involve a change in the basic law underlying the parcel of land in question. The zoning applicable to the parcel as indicated on the zoning map remains the same.”). Nonetheless, a failure to understand special exceptions in the world of land use and zoning is understandable. Local jurisdictions have inconsistent statutory criteria for approving special exceptions. The Maryland Code provides a definition of special exception that may be internally contradictory. Finally, the interaction of common law standards with statutory criteria has created a hodgepodge of special exception approval standards throughout Maryland.

Because most readers of the Maryland Bar Journal are presumably unfamiliar with land use law, it is necessary to establish some basic land use, zoning, and planning principles. Generally, land use authority is delegated to a local jurisdiction (county or municipality) that, in enacting a comprehensive zoning ordinance, “divides an area geographically into particular use districts, specifying certain uses for each district.” People’s Counsel for Baltimore County

v. Loyola College, 406 Md. 54, 70 (2008). In so doing, the local jurisdiction typically establishes single-use districts such as residential, commercial or industrial zones, named Euclidean zones after the seminal case of Village of Euclid, Ohio v. Ambler Realty, Co., 272 U.S. 365 (1926). The local government may also establish mixed-use zones which permit a combination of uses such as various intensities of commercial and residential uses. Additionally, local jurisdictions may establish “floating zones,” which are a more flexible zoning “device” than Euclidean zoning. Mayor & Council of Rockville v. Rylyns Enterprises, Inc., 372 Md. 514, 539 n.15 (2002). Within each of these zoning districts, the local jurisdiction will determine what uses are “permitted” and which are “prohibited.” “A permitted use in a given zone is permitted as of right within the zone, without regard to any potential or actual adverse effect that the use will have on neighboring properties.” Loyola, 406 Md. at 71. A prohibited use, on the other hand, is not allowed in the zone. For example, a permitted use in a low-density residential zone would be a single-family dwelling, but a prohibited use in that zone would be a cement manufacturing plant.

“The special exception,” the Court of Appeals has explained, “adds flexibility to a comprehensive legislative zoning scheme by serving as a ‘middle ground’ between permitted uses and prohibited uses in a particular zone.” Id. Where a permitted use is allowed “as of right” and a prohibited use is never allowed, a “special exception, by contrast, is merely deemed prima facie compatible in a given zone” and “requires a case-by-case evaluation by an administrative zoning body or officer according to legislatively-defined standards.” Id. An example of this “middle ground,” which has appeared in more than one reported appellate decision, is a special exception to allow a funeral

November 2018 4 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL

home in a residential district. Schultz v. Pritts, 291 Md. 1 (1981); Clarksville Residents Against Mortuary Defense Fund, Inc. v. Donaldson Properties, 453 Md. 516 (2017); Anderson v. Sawyer, 23 Md. App. 612 (1974).

Special exceptions require an additional level of scrutiny and typically require a hearing. John J. Delaney et al., Handling the Land Use Case 19 (3d ed. 2012) (“Qualifying for a special exception usually requires a public hearing before an administrative board, such as a board of appeals, board of zoning adjustment or a hearing examiner.”). Logic dictates that this added layer of review is necessary because, presumably, uses requiring a special exception such as landfills, sand and gravel operations, gas stations, and auto and truck recycling facilities, will potentially have adverse effects such as noise, traffic, congestion, environmental concerns, smells, etc. See e.g., Anne Arundel Cnty. Code § 18-6-103.

Uses that require special exception approval are not a homogeneous group and their purported adverse impacts may not be easily identifiable. Local governments also designate special exception uses with less obvious or arguably non-existent inherent adverse effects. Funeral homes, for example, may cause “vague and generalized fear,” such as worries about the structure being an eyesore or attracting bugs, but may, in fact, have minimal tangible impacts like a

slight increase in traffic. See Anderson, 23 Md. App. at 623–24. Solar energy generating facilities are special exception uses in certain zoning districts, but beyond any viewshed impacts, they generate no noise, traffic, dust or odor. See Anne Arundel Cnty. Code 18-6-103.

On the other end of the spectrum from uses like rubble landfills (with obvious inherent adverse effects), are uses that are designated as special exception uses even though they arguably have the same impact as permitted uses in the zoning district. For example, residential uses such as workforce housing, housing for the elderly of moderate means, or duplex dwelling units would have similar adverse impacts to other permitted residential uses but are, nevertheless, treated as special exception uses in certain residential zoning districts in Anne Arundel County. Anne Arundel Cnty. Code § 18-4-106. Further demonstrating the lack of uniformity is that jurisdictions do not treat the same use similarly (e.g., a fast-food restaurant is a permitted use in Anne Arundel County but it is a special exception use in the City of Annapolis). Compare Anne Arundel Cnty. Code § 18-5-101 with City of Annapolis Code § 21.48.030.

The inconsistent nomenclature used by Maryland counties and municipalities tends to increase confusion. While the Court of Appeals has said that the “terms ‘special exception,’ ‘conditional use,’ and ‘special use permit’ are

November 2018 5 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL 1925 Old Valley Road • Suite 2 • Stevenson, MD 21153 P.O. Box 219 • 410.625.1100 • FX410.625.2174 The Law Offices of Julie Ellen Landau

30 years’

provide a broad depth of knowledge in all family law matters. In our centrally located office in Greenspring Valley,

you with efficiency and a real “get it done” attitude.

ALL FAMILY LAW MATTERS LITIGATION APPEALS MEDIATION NEUTRAL CASE EVALUATION COLLABORATIVE LAW

With over

experience we

we advocate for

We solve problems.

understood to be interchangeable,” Montgomery Cnty. v. Butler, 417 Md. 271, 275 n.1 (2010), that is not true in all jurisdictions. In particular, in Anne Arundel County, a conditional use is a permitted use with conditions, but does not require a hearing. Compare Anne Arundel Cnty. Code 1810-101 et seq. with Anne Arundel County Code § 18-11-101 et seq. In some counties, the term conditional use is synonymous with the term special exception. See Howard County Zoning Regulations § 131.0 et seq.

At the state level, the Land Use Article of the Maryland Code provides a definition of “special exception” that applies to most jurisdictions in the state (but not those governed by the Regional District Act), and defines that term as “a grant of a specific use that: (1) would not be appropriate generally or without restriction; and (2) shall be based on a finding that: (i) the requirements of zoning law governing the special exception on the subject property are satisfied; and (ii) the use on the subject property is consistent with the plan and is compatible with the existing neighborhood.” Md. Code (2012, 2017 Supp.), Land Use, 1-101(p). This definition—which is arguably internally inconsistent, as it is a use that may “not be appropriate generally” and yet must also be consistent with the local jurisdiction’s general development plan—does not incorporate any standards established by the common law.

The modern landmark decision guiding special exception approvals is Schultz v. Pritts, 291 Md. 1 (1981). In Schultz, the Court of Appeals said that special exception uses are presumptively compatible with the permitted uses in that district. Id. at 21. The conclusion in Schultz, which is regularly quoted in case law, is that “there are facts and circumstances that show that the particular use proposed at the particular location proposed would have any adverse effects above and beyond those inherently associated with such a special exception use irrespective of its location within the zone.” Id. at 22. Admittedly, the principles of this test can be difficult to distill, even for the seasoned land use practitioner. To the public, the words can be meaningless.

The practical challenge of applying the Schultz test was evident in People’s Counsel for Baltimore County v. Loyola College, 406 Md. 54 (2008), where a college proposed to develop a spiritual retreat center (a special exception use), in a residential zone. Id. at 58. The Baltimore County Board of Appeals granted the college’s special exception application over citizen opposition. Id. at 59. On appeal, the question was whether Schultz required the Board to compare the potential adverse effects of the proposed use at the subject property to the potential adverse effects at other, similarly zoned properties (i.e., whether a spiritual retreat center might have less impact somewhere else). Id. at 66. The opponents argued that “Schultz compels a district-wide comparative geographic analysis of effects in each special exception.” Id at 94. The college, on the other hand, countered that special exception case law did not require a “multiple site analysis” and only an evaluation of the impacts at the proposed development site, alone, is required. Id. at 105–

07. The Court of Appeals concluded that no “comparative, multiple site impact analysis” was required. Additionally, the Court reaffirmed the presumption of compatibility of special exception uses:

inherent effects [of a special exception use] notwithstanding, the legislative determination necessarily is that the uses conceptually are compatible in the particular zone with otherwise permitted uses and with surrounding zones and uses already in place, provided that, at a given location, adduced evidence does not convince the body to whom the power to grant or deny individual application is given that actual incompatibility would occur.

Id. at 106.

An issue arises when Schultz is considered in conjunction with local requirements that must be proven at a special exception hearing. Typically, a local jurisdiction adopts findings that a zoning body must make before a special exception is granted. For example, Anne Arundel County requires the following findings be made, and these findings explicitly include the Schultz test:

a. Requirements. A special exception use may be granted only if the Administrative Hearing Officer makes each of the following affirmative findings:

1. The use will not be detrimental to the public health, safety, or welfare;

2. The location, nature, and height of each building, wall, and fence, the nature and extent of landscaping on the site, and the location, size, nature, and intensity of each phase of the use and its access roads will be compatible with the appropriate and orderly development of the district in which it is located;

November 2018 6 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL

“There are facts and circumstances that show that the particular use proposed at the particular location proposed would have any adverse effects above and beyond those inherently associated with such a special exception use irrespective of its location within the zone.”

In addition to the numerous esteemed awards, accolades, and inductions from the legal community, Debbie Potter is this year’s proud recipient of the Maryland Association for Justice’s “Trial Lawyer of the Year” award. As a recipient of this prestigious award, she has been identified as a leader who has made the greatest contribution to the public interest by trying or settling cases that further the goal of keeping Maryland families safe by defending civil rights, consumer rights, workers’ rights, and human rights.

At Potter Burnett Law, our pride of personal injury lawyers has the legal experience, leadership, and proven track record to represent you and your family. Our award-winning lawyers are focused on fighting for the damages you deserve, while protecting your pride and justice in every case. Acclaimed personal injury attorneys Deborah L. Potter, Suzanne V. Burnett, and Andrew T. Burnett understand the importance of standing by your side. Our compassionate and experienced team will confidently represent you, defend your loss, and litigate on behalf of your interests.

Welcoming cases in the areas of car crashes, nursing home abuse, and medical malpractice.

November 2018 7 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL CALL FOR A FREE CONSULTATION 301.850.7000 16701 Melford Blvd • Suite 421 • Bowie, MD 20715 PotterBurnettLaw.com Let our pride, protect yours. *Each case is different and the law firm’s past record in obtaining favorable awards, judgments, or settlements in prior cases is no assurance of success in any future case. pride AWARD-WINNING It Takes a Lion to be a Leader

January 2018 Jury Verdict $1,100,000 CHARLES COUNTY CIRCUIT COURT * February 2018 Jury Verdict $993,000 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA SUPERIOR COURT March 2017 Jury Verdict $1,050,000 BALTIMORE CITY CIRCUIT COURT * April 2017 Jury Verdict $1,122,286 HARFORD COUNTY CIRCUIT COURT * * Car Accidents • Nursing Home Negligence • Medical Malpractice

3. Operations related to the use will be no more objectionable with regard to noise, fumes, vibration, or light to nearby properties than operations in other uses allowed under this article;

4. The use at the location proposed will not have any adverse effects above and beyond those inherently associated with the use irrespective of its location within the zoning district;

5. The proposed use will not conflict with an existing or programmed public facility, public service, school, or road;

6. The proposed use has the written recommendations and comments of the Health Department and the Office of Planning and Zoning;

7. The proposed use is consistent with the County General Development Plan;

8. The applicant has presented sufficient evidence of public need for the use;

9. The applicant has presented sufficient evidence that the use will meet and be able to maintain adherence to the criteria for the specific use;

10. The application will conform to the critical area criteria for sites located in the critical area; and

11. The administrative site plan demonstrates the applicant’s ability to comply with the requirements of the Landscape Manual.

Anne Arundel Cnty. Code 18-16-304 (emphasis added).

Montgomery County has modified the Schultz test. The Montgomery County Zoning Ordinance explicitly requires its hearing examiner to consider both inherent effects (e.g., noise associated with deliveries at a senior living facility) and non-inherent effects (e.g., noise from a late-night dance club at a senior living facility in a residential neighborhood):

g. will not cause undue harm to the neighborhood as a result of a non-inherent adverse effect alone or the combination of an inherent and a non-inherent adverse effect in any of the following categories:

i. the use, peaceful enjoyment, economic value or development potential of abutting and confronting properties or the general neighborhood;

ii. traffic, noise, odors, dust, illumination, or a lack of parking; or

iii. the health, safety, or welfare of neighboring residents, visitors, or employees.

Montgomery Cnty. Zoning Ordinance, Article 59-7.3.1(E) (1)(g) (emphasis added).

In Montgomery County v. Butler, 417 Md. 271 (2010), the Court of Appeals approved Montgomery County’s legislative departure from the Schultz presumption of compatibility. The Court of Appeals said: “In reviewing a decision of a zoning board approving or denying an application for a special exception, the emphasis must be first and fore-

most on identifying the relevant and prevailing zoning ordinance. Only then, after determining whether the zoning ordinance is silent on the matters to which Schultz and its progeny speak, may the Schultz line of cases become pertinent and controlling.” Butler, 417 Md. at 306.

In Allegany County, no special exception criteria whatsoever have been adopted and the common law tests and the land use article presumably control.

Without action by the state to establish more uniform special exception standards, practitioners must be aware of differences that exist among each county and municipality, which may include conflicting statutory and common law standards. Practitioners must determine whether their respective jurisdictions have adopted, rejected or are silent with respect to the Schultz test. Finally, the adverse effects of special exception uses, if any, must be analyzed based on the specific and actual area of the proposed development site, as opposed to hypothetical alternatives or a geographical comparative analysis.

Because zoning is predominantly a function of local government, it is unlikely that there will be more uniform standards governing special exceptions in the future. Judge Harrell, now recently retired from the Court of Appeals, captured in an apt analogy why uses end up requiring special exception approval and why there is no guarantee as to how land uses in Maryland’s jurisdictions will be classified: The local legislature, when it determines to adopt or amend the text of a zoning ordinance with regard to designating various uses as allowed only by special exception in various zones, considers in a generic sense that certain adverse effects, at least in type, potentially associated with (inherent to, if you will) these uses are likely to occur wherever in the particular zone they may be located. In that sense, the local legislature puts on its “Sorting Hat” and separates permitted uses, special exceptions, and all other uses. That is why the uses are designated special exception uses, not permitted uses.

Loyola, 406 Md. at 106; see also id. at 106 n. 33 (“In the Harry Potter series of books, the “Sorting Hat” is a magical artifact that is used to determine in which house (Gryffindor, Hufflepuff, Ravenclaw or Slytherin) first-year students at Hogwarts School of Wizardry and Witchcraft are to be assigned. After being placed on a student’s head, the Sorting Hat measures the inherent qualities of the student and assigns him or her to the appropriate house.”).

Mr. Goldsmith and Ms. Roberts-Satinsky are associates in the Annapolis office of Linowes and Blocher LLP. Mr. Goldsmith’s practice focuses on land use in Prince George’s County and Anne Arundel County and real property-related litigation. Ms. Roberts-Satinsky’s practice focuses on land use in Anne Arundel County and environmental law throughout Maryland.

November 2018 8 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL

1-HOUR DEEP-DIVE AUDIO CLE

in niche federal law topics

LEARN MORE: msba.org/CLEaudio

A Possible Avenue to Reach Judicial Review of a “Garden Variety” Administrative Decision Through Alleging Common Law

Taxpayer Standing

By Timothy Dugan

Recent Maryland Court of Appeals decisions suggest that a person may achieve judicial review from an adverse “garden variety” administrative proceeding by properly alleging “common law taxpayer standing” instead of “property owner standing,” also referred to as “proximity standing.” See Anne Arundel County v. Bell, 442 Md. 539, 113 A. 3d 639 (2015) (“Bell”); and State Center, LLC v. Lexington Charles Limited Partnership, 438 Md. 451, 92 A. 3d 400 (2014) (“State Center”). See also, Greater Towson Council of Community Associations v. DMS Development, LLC, 234 Md.App. 388, 172 A.3d 939 (Md.App. 2017) (“Towson”). Preliminarily, the Courts use the term “taxpayer standing.” I am using the words “common law taxpayer standing” to highlight the common law source of the right, rather than by statute, and to distinguish it from access to the courts through allegations that are grounded on a person’s proximity to the property in question. Also, the term “garden variety” administrative proceeding is intended to refer to, for example, a special exception application proceeding before a board of appeals for a non single family use in a residentially zoned area, such as certain senior housing or a dental office.

The tests for establishing common law taxpayer standing do not appear so burdensome not only for “garden variety” administrative proceedings but also for appeals of legislative actions, like master plans and comprehensive rezonings. For this reason, the dissenting judges’ concern in Bell that a party seeking judicial review, under common law taxpayer standing, will have a difficult time reaching the courts may be misplaced. Bell, 442 Md. at ___, 113 A.

3d at 672.

Before discussing common law taxpayer standing, a short summary of the Court’s elements for alleging property owner/proximity standing may be helpful. A party who participated in the administrative proceeding and whose land is adjoining or confronting the property whose entitlements are under dispute meets the prima facie test for standing. For a property owner who participated in the administrative proceeding and whose property is located further away, “almost prima facie” cases, as described in detail in Ray v. Mayor & City Council of Baltimore, 430 Md. 74, ___, 59 A.3d 545, 555 (2013) (“Ray”), (and as referenced in State Center, 438 Md. at ___, 92 A. 3d at 449), the Ray Court noted:

Although there is no bright-line rule for who qualifies as ‘‘almost’’ prima facie aggrieved, we have found no cases, in which a person living over 2000 feet away, has been considered specially aggrieved. Rather, as we discussed above, this category has been found applicable only with respect to protestants who lived 200 to 1000 feet away from the subject property.

In addition, such almost prima facie property owners must establish some additional harm that distinguished their harm from those of the general public, known as a “plus factor.” Ray, 430 Md. at ___, 59 A.3d at 551. Examples of plus factors are: harm from a change in the character of the neighborhood, harm from increased traffic, and harm from the project interrupting sight or views. Ray, 430 Md. at ___, 59 A.3d at 556. A litigant must actually own the land being affected; thus, a

community association that owns no land may not be the entity that is the “anchor” for the appeal. See Towson. A local law or regulation may establish reasonable limits on statutorily established property owner standing. See Sugarloaf Citizens Association v. Department of Environment, 344 Md. 271, ___, 686 A. 2d 605, 613 (1996), and as cited in Chesapeake Bay Foundation v. DCW Dutchship Island, 439 Md. 588, ___, 97 A. 3d 135, 141 (2013). Property owner/ proximity standing allegations do not provide access to the courts when opposing a comprehensive rezoning. See Bell. A thorough discussion of property owner/proximity standing may be found in the recent Towson decision by the Court of Special Appeals decision as well as Bell and StateCenter

There are, however, limitations with respect to property owner/proximity standing that a party might be able to overcome by successfully alleging the necessary elements of common law taxpayer standing. For instance, in State Center, the Court explains that a taxpayer, who is able to make the allegations properly, has access to the courts arising from a common law right, not one arising from a statute. The common law taxpayer standing doctrine permits taxpayers to seek the aid of courts, exercising equity powers, to enjoin illegal and ultra vires acts of public officials where those acts are reasonably likely to result in pecuniary loss to the taxpayer. [Citing, 120 West Fayette Street, LLLP v. Mayor of Baltimore, 407 Md. 253, 267, 964 A.2d 662, 669–70 (2009)]

[C]ourts often require that the com-

November 2018 10 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL

. . .

plainant not have an adequate remedy at law. [citations omitted.] Where the complainant does not have an adequate remedy at law, however, the common law demands that we permit the suit unless the General Assembly has preempted this common law right.

State Center, 438 Md. at ___, 92 A. 3d at 451, and at 454.

The Court further explains common law taxpayer standing as follows: In other words, [common law taxpayer standing], when asserted properly, provide[s] both the cause of action (or claim) and the right of the individual to assert the claim in the judicial forum. Moreover, [common law taxpayer standing] provide[s] [an] avenue[] for a complainant to challenge what may be termed as a ‘public wrong.’

State Center, 438 Md. at ___, 92 A. 3d at 439.

The Court in State Center outlines the allegation elements for common law taxpayer standing. State Center, 438 Md. at ___, 92 A. 3d at 451, et seq. which are paraphrased below.

The complainant must be a taxpayer (and not a pass through entity). The person must pay the type of taxes that are the subject matter of the grounds for the taxpayer’s standing.

By inference, but not explicitly set forth in the case law regarding common law standing, the taxpayer must remain in the case throughout the appeal. See Towson, a proximity standing case. In Towson, the appeal was dismissed for lack of standing, because of the withdrawal of the only party who held the right to judicial appeal, a property owner.

It appears that “piggyback standing” would be allowed, where one or more persons would be allowed to participate in the appeal, even though they do not have independent judicial standing themselves, as long as those who hold common law taxpayer standing remain. An example of the Court’s determination is found in Sugarloaf Citizens Association v. Department of Environment, 344 Md. 271, ___, 686 A. 2d 605, 618 (1996).

Where there exists a party having standing to bring an action, we shall not ordinarily inquire as to whether another party on the same side has standing.

The taxpayer must allege sufficiently that the case is proceeding on behalf of the taxpayer and on behalf of all other taxpayers similarly situated. The allegation will be deemed adequate if it is stated explicitly or implicitly (by necessary implication). State Center, 438 Md. at ___, 92 A. 3d at 457-461. The prudent appellant would allege explicitly that the appeal is being brought on behalf of the taxpayer and all taxpayers similarly situated.

The next element explained in State Center is the allegation that the governmental action is a primary action and that such action is illegal or ultra vires. State Center, 438 Md. at ___, 92 A. 3d at 462. In Bell, the Court cites several cases where taxpayer standing was upheld to challenge administrative determinations in the courts. See Bell, 442 Md. at _____, 113 A. 3d at 663 664. The cited cases do not involve a “garden variety” administrative appeal, such as an appeal of a board of appeals decision; however, the nature of an alleged illegal act or alleged ultra vires action should not be limited to just those fact patterns. In the case of an administrative appeal, the taxpayer would allege that a board of appeals, for example, misinterpreted the zoning provision and, thus, illegally applied the requirement, or that the board of appeals exceeded its authority, because the ruling was not within the bounds of the board’s authority. The standing determination might have been different in the case, Committee for Responsible Development on 25th Street v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 137 Md. App. 60, 767 A.2d. 906 (2001), if common law standing allegations were plead correctly. A person unsuccessfully argued standing as a taxpayer only under the now MD Code, Land Use Section 10 501 “Procedure, Baltimore City” standing for judicial review, which is based on “property owner standing” or “proximity standing.” The appellant did not allege appellate standing under

common law standing.

The common law taxpayer standing allegations must include that the illegality or ultra vires action caused or will cause the taxpayer a “pecuniary loss or an increase in taxes.” In Bell, the Court instructed that if individual taxpayers (in that case, opposing the comprehensive rezoning action) had alleged in its original pleadings, not later, that it would suffer a pecuniary loss or an increase in taxes, the persons might have achieved taxpayer standing. In footnote 30, the Court references a memorandum where there were allegations of property value decrease [arguably a pecuniary loss], tax assessment increases [an express element of taxpayer standing], increases in traffic, and alteration of neighborhood character. The Court notes:

As these statements were not made in support of allegations contained in the Complaint for Declaratory Judgment nor the Amended Petition for Judicial Review, they are not available to make out a prima facie showing of the ‘‘harm’’ required by taxpayer standing.

Bell, 442 MD. at ____, 113 A. 3d at 667.

The types of harm alleged as arising from illegal or ultra vires acts that the Court has been asked to consider include: harm from invalid statutes, harm from decreases in governmental efficiency, harm from costs to fend off illegality, and harm from the waste of public funds. State Center, 438 Md. 451, ___, 92 A. 3d at 466-467.

The Court also requires that the person allege (that is, not establish before the appeal is underway) that it is reasonable to conclude that a nexus exists between the alleged illegal or ultra vires actions and the person’s allegation that such acts will cause pecuniary loss or an increase in taxes. State Center, 438 Md. 451, ___, 92 A. 3d at 472. For the individual taxpayer, the amount of the alleged loss or increase need not be significant. State Center, 438 Md. 451, ___, 92 A. 3d at 477.

It seems that a person who opposes a garden variety administrative decision could allege common law taxpayer standing as follows, using some hypo-

November 2018 11 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL

thetical facts for illustration purposes:

1. The person is claiming standing through common law taxpayer standing.

2. Whether the taxpayer person did or did not participate in the administrative proceeding might be irrelevant.

3. The person is a taxpayer. In this hypothetical, assume that the taxpayer pays real property taxes and individual state and local county or city income taxes.

4. The person is bringing the appeal on its own behalf and on behalf of the other taxpayers similarly situated, in the role of a private attorney general. In this example, the “attorney general” would allege that it is be looking out for the taxpayers who live not only as adjoining and confronting property owners/ taxpayers but also for those who live further away in the general neighborhood or even further away and perhaps pass by the subject property every day or very infrequently, if at all. The “attorney general” would allege that the class’s property values will depreciate and their taxes will increase because of the additional burden from the proposed to-be-redeveloped property. The fundamental argument is that the common law taxpayers would not be limited to those who could satisfy “property owner standing/aka proximity standing.”

5. Assuming that the taxpayers remain and anchor the appeal, non-taxpaying entities like community associations could also participate even though they are not taxpayers. (Sugarloaf)

6. Allege that the board of appeals (in this example), an administrative body and a government official, illegally and ultra vires ruled that:

a. The zoning statute allows height to be measured from “X” location versus “Y” location.

b. The zoning statute allows setback to be measured from “X” location versus “Y” location.

c. The project would be compatible with the neighborhood generally.

d. The project would not unduly burden the roads.

e. The project would not unduly impact the environment.

f. The architecture is compatible with the neighborhood.

g. The applicant must install off site landscaping and the government must assume maintenance responsibility.

7. The taxpayer would allege that if the project were allowed to be developed, the common law taxpayers would suffer pecuniary losses. Their homes would be less valuable because of the presence of the project and its activities in the neighborhood. The taxpayers would pay more real property taxes and individual in-

come taxes. The taxes would be reasonably expected to increase to construct and maintain new infrastructure that will not be paid for entirely by the applicant, including, off site roadways, off site sidewalks, schools, and off site stormwater management facilities.

8. The remedy of not allowing the project to be approved, based on the alleged illegal and ultra vires actions of the government officials, will be that the opposition will not suffer pecuniary losses and will not pay more taxes arising from the project.

For the above reasons, it seems that securing judicial review might be easier using adequately pled common law taxpayer standing allegations than allegations under “property owner/proximity standing.”

Mr. Dugan is Co-Chair of the Zoning and Land Use Practice Group at Shulman Rogers in Potomac, Maryland.

November 2018 12 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL

410-296-4408 www.firstmdtrust.org

November 2018 13 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL

Takings in Time:

Legal Challenges to Land Use Moratoria Under the Fifth Amendment and Fair Housing Act

By Thomas G. Coale

As public infrastructure has lagged behind residential development and public polling shows more support for anti-development policies, jurisdictions across Maryland have implemented de juris or de facto development moratoria that have significantly constrained the use of private property. Federal courts have recognized such blanket controls as legitimate planning tools that may be used to stop development while new regulations are being considered. Nevertheless, property owners often turn to their counsel to identify what remedies they may have, if any, to remove this restraint or receive compensation.

Frustrated land owners may be disappointed to hear that both federal and Maryland state courts have viewed land use moratoria favorably in the context of the Fifth Amendment. Understanding the temporal value of property, a present constraint may be allowed so long as there is a promise of future value. Nevertheless, there are still instances in which poorly considered land use moratoria may be overturned or result in the payment

of just compensation. Similarly, land use moratoria may also be vulnerable to challenge under the federal Fair Housing Act when they operate to exclude certain housing products, such as multi-family homes.

Land Use Regulation and the Takings Clause

The Fifth Amendment provides: “No person shall . . . be deprived of

November 2018 14 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL

Property owners often turn to their counsel to identify what remedies they may have, if any, to remove this restraint or receive compensation.

life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.” Although local jurisdictions are afforded significant deference by federal courts in the application of land use regulations, the courts have recognized that there is a point past which the police power manifests as a “regulatory taking”.

In contrast to those circumstances in which the government physically takes possession of an interest in property, a “regulatory taking” occurs when a property is stripped of all economic value due to the constraints of land use regulation. While manifestly different in terms of the possessory interest, the Supreme Court has held that both categories of taking require compensation under the Fifth Amendment. First English Evangelical Lutheran Church v. County of Los Angeles, 482 U.S. 304, 318, 107 S.Ct. 2378, 2387, 96 L.Ed.2d 250 (1987) (“[T]emporary’ takings which ... deny a landowner all use of his property, are not different in kind from permanent takings, for which the Constitution clearly requires payment.”).

There ar two types of regulatory takings. The first is a per se taking which deprives the landowner of all economic use of its property. This is most commonly referred to as a Lucas taking or a “per se” total taking. Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council, 505 U.S. 1003, 1018, 112 S.Ct. 2886, 2894-95, 120 L.Ed.2d 798 (1992). In Lucas, a property owner filed for just compensation after a local regulation prevented him from building on two coastal lots. Due to the fact that there could be no other economical use of the land, the Court found that his claim for a taking under the Fifth Amendment could proceed.

If the taking is not per se, and the property still retains some, albeit diminished, economically beneficial uses of its land, then the Court will evaluate the fairness of the regulation under a multi-factor test set forth in Penn Central Transportation Co. v. City of New York wherein courts are to weigh the necessity of the governmental regulation against the private interests

of the land owner. 438 U.S. 104, 98 S. Ct. 2646, 57 L. Ed. 2d 631 (1978). These factors include “the economic impact of the regulation on the claimant and, particularly, the extent to which the regulation has interfered with distinct investment backed expectations,” as well as the “character of the governmental action.” Id. at 124, 107 S.Ct. at 2660. This test is designed to recognize that every government regulation affects property value in some sense and that assessing compensation for every such diminishment of value would grind government to a halt.

Temporary Regulatory Takings

Up until 1987, the Supreme Court had not ruled on whether temporary regulation could manifest as a regulatory taking. In First English Evangelical Lutheran Church v. County of Los Angeles, the Court found in the affirmative, holding that property owners had the right to be compensated for temporary regulatory takings. 482 U.S. 304, 107 S.Ct. 2378, 96 L.Ed.2d 250 (1987). In that case, the plaintiff, a religious facility, owned land in a California creek basin, which it operated as a retreat and campground. After a flood destroyed the church’s buildings in the basin, Los Angeles County adopted an “interim ordinance” that precluded structures from being rebuilt therein. The church filed suit, claiming, in part, that the ordinance “denies [appellants] all use” of the property, and sought damages for the taking.

After claims for just compensation had been struck in state court, the United States Supreme Court reversed. The Court held that the Fifth Amendment

applied to permanent and temporary regulatory takings alike and that property owners subject to such regulations may recover damages for inverse condemnation. The Court held that “[i]t is axiomatic that the Fifth Amendment’s just compensation provision is ‘designed to bar Government from forcing some people alone to bear public burdens which, in all fairness and justice, should be borne by the public as a whole.’” Id. at 318, 107 S.Ct. at 2388 (citations omitted). As emphasized by later court decisions, First English did not hold that the property owner was entitled to such damages or that a taking had occurred. Rather, this holding was limited to the proposition that a claim for inverse condemnation may be brought in response to a temporary regulatory taking.

The Supreme Court refined the First English holding in Tahoe-Sierra Preservation Council v. Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, which held that a temporary thirty-two month land-use moratorium did not constitute a per se “total taking” of the property. 535 U.S. 302, 122 S. Ct. 1465, 152 L.Ed.2d 517 (2002). The Court found that when evaluating the elimination of a property’s value, the property should be viewed in both a physical and temporal capacity (i.e., the property’s value over time). Id. at 331-32, 122 S. Ct. at 1483-84. In this context, a temporary moratorium cannot constitute a per se taking, as the property will recover its value as soon as the prohibition is lifted. The Court further reasoned that the interest in facilitating informed decision-making by regulatory agencies counsels against adopting a rule that would impose such severe costs on their deliberations and that “[m]oratoria are an essential tool of successful development.” Id. at 304, 122 S. Ct. at 1469.

After rejecting the application of Lucas, the Court applied the Penn Central multi-factor test and held that the duration of the moratorium was reasonable to allow the governmental agency time to develop a regional planning document. Nevertheless, in dicta the Court noted that mortatoria lasting

November 2018 15 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL

Courts are to weigh the necessity of the governmental regulation against the private interests of the land owner.

longer than one year require “special skepticism”. Tahoe-Sierra, 535 U.S. at 304, 122 S.Ct. at 1470.

Despite the language of skepticism, the Supreme Court has not set a “bright line” rule on how long is “too long” for temporary regulatory takings. Rather, the reasonableness of the duration of the moratorium is evaluated on a case-by-case basis in relation to the purpose for the freeze in development and the economic impact on the property owner. Rolling moratoria, or a moratorium with no set end date, would not be found reasonable when held against the investment-backed expectations of land owners. See City of Monterey v. Del Monte Dunes at Monterey, Ltd., 526 U.S. 687, 119 S.Ct. 1624, 143 L.Ed.2d 882 (1999) (Court upheld the award of regulatory takings damages based on a pretextual refusal to accept one development plan after another, when each plan complied with the city’s previous demands).

Maryland Case Law

The most relevant case for evaluating temporary takings under Maryland law is Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission v. Chadwick. 286 Md. 1, 405 A.2d 241 (1979). In that case, the Court of Appeals held that a park commission resolution placing property in reservation for up to three years, without any reasonable uses permitted as of right, was tantamount to a “taking” in the constitutional sense and, because the resolution did not provide for payment of just compensation, the resolution was unconstitutional. The court applied the multi-factor test under Penn Central, finding that the “resolution does not merely circumscribe a beneficial use of the property; it inhibits all beneficial use for up to three years, without any guarantee that the property will be acquired in the future.” Id. at 16, 405 A.2d. at 248.

There are two other opinions from the Court of Special Appeals that bear relevance here. In Steel v. Cape Corp., the Court of Special Appeals held that an adequate public facilities ordinance that prohibited the zoning authority

November 2018 16 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL September 2018 16 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL ...when the estate administration turns to litigation. 5300 Dorsey Hall Drive, Suite 107 Ellicott City, Maryland 21042 Phone: 410-696-2405 Fax: 877-732-9639 kinghall-law.com

counsel you can trust...

Refer to

from rezoning a parcel to residential uses unless the applicant could establish adequate school capacity was an unconstitutional regulatory taking.

111 Md. App. 1, 677 A.2d 634 (1996). In that case, the plaintiff bringing suit had attempted to have his parcel rezoned from undeveloped open space to residential. There was an acknowledged mistake in the original zoning, as the open space zone was only to be applied to parcels owned by community associations. The court concluded that this was a per se taking under Lucas, holding that “[w]hile a situation where such adequacy of facility statutes slow growth might be constitutionally permissible, it is not constitutionally permissible where the type of growth reduction occurs at the expense of a property owner’s loss of viable economic use of his property.”

Id. at 23, 677 A.2d at 645.

The Steel case only applies to per se takings and not the multi-factor weighing of interests set forth in Penn Central. The Steel court observed that to the extent the ordinance had only precluded an increase in residential density there would remain a viable economic use if there was an existing residential use of the property. Id at 36, 677 A.2d at 651 (“We perceive that, if the present zoning of a subject property is other than [Open Space] and permits some viable residential or reasonable commercial use, the statutory scheme as applied to those types of properties may withstand ‘takings’ scrutiny.”).

The Maryland Court of Special Appeals specifically addressed the constitutionality of temporary takings under a development moratorium in S.E.W. Friel v. Triangle Oil Company. 76 Md. App. 96, 543 A.2d 863 (1988). In that case, the court upheld a nine-month development moratorium in Queen Anne’s County. Due to the fact that the appellant had not sought just compensation, the court did not take the occasion to apply the holding of First English as it relates to temporary regulatory takings, but rather limited its scope to whether such moratoria were constitutional. Finding that it was, the

court held that the “Fifth Amendment does not prohibit the taking of private property; it merely makes compensation a condition of the exercise of that power.” Id. at 104, 543 A.2d. at 867.

Maryland appellate courts have not had the opportunity to evaluate temporary moratoria since the Supreme Court’s 2002 Tahoe-Sierra decision. As such, there have been no cases evaluating the reasonableness of temporary moratoria or applying the Penn Central test to determine whether there has been a compensable taking related to the implementation of moratoria.

Fair Housing

Understanding the narrow grounds upon which a temporary land development moratorium may be found to require just compensation under the Fifth Amendment, it is worth considering a lesser known avenue for challenging restrictive zoning practices under the federal Fair Housing Act.

On November 10, 2016, the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (“HUD”) issued a joint statement updating guidance about how the federal Fair Housing Act applies to state and local land use and zoning laws. The memorandum identified five categories of regulatory action that may violate the Fair Housing Act, one of which is relevant here:

• Prohibiting or restricting the development of housing based on the belief that the residents will be members of a particular protected class, such as race, disability, or familial status, by, for example, placing a moratorium on the development of multifamily housing because of concerns that the residents will include members of a particular protected class.

Joint Statement of the Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Department of Justice, State and Local Land Use Laws and Practices and the Application of the Fair Housing Act (Nov. 10, 2016), https:// www.justice.gov/opa/file/912366/ download.

Land use or zoning practices that result in an unjustified discriminatory effect or disparate impact on a particular group of persons, or otherwise perpetuates segregated housing patterns, may be found to violate the Federal Housing Act and give rise to a cause of action under federal law. It is notable that the two federal departments explicitly identified land use moratoria as a potential violation of the Fair Housing Act. While it is unlikely that a blanket application of a development moratorium would satisfy the more specific requirements that would constitute a violation of the Act, particularized prohibitions, such as a moratorium on multifamily or apartment dwellings, would likely be vulnerable to challenge in federal court.

Conclusion

State and local governments have significant discretion in constraining property rights for the sake of public planning and ensuring adequate public facilities. Nevertheless, these powers have limits. When land use regulations arbitrarily rob property owners of their development rights for a prolonged or uncertain period of time, federal courts will find that a regulatory taking has occurred. The absence of case law defining those limits is more likely the consequence of local jurisdictions self-reversal than the imposition of the courts.

In light of the political pressures that bring land use moratoria into existence, attorneys should consider whether the restraints on development have a disparate effect on protected communities or otherwise perpetuate the segregated housing established by decades of mortgage redlining. If so, a case that may originally have been filed as inverse condemnation may be better suited as a challenge to the legality of the law under the Fair Housing Act.

Mr. Coale is an attorney with the law firm of Talkin & Oh, LLP, in Ellicott City, Maryland, where he regularly represents property owners in zoning matters and real estate litigation. He may be reached at tcoale@talkin-oh.com.

November 2018 17 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL

HARVESTING THE SUN ON MARYLAND FARMLAND

LOCAL ZONING RESTRICTIONS FOR SOLAR FIELDS

By Casey L. Cirner

By Casey L. Cirner

The ideal location for a utility scale solar generation facility (solar farm) is a large swath of flat, cleared land (i.e., farmland). The availability of agricultural land, either through purchase or lease, coupled with Maryland’s renewable energy goals and the community solar pilot project (discussed below), has many Maryland counties seeing an influx of zoning and regulatory applications for solar farms on agricultural land. These same counties are concerned that the solar projects will diminish the available agricultural land and are tightening zoning regulations to further restrict its use. But, the effectiveness of these local efforts remains to be seen because, typically, State law impliedly preempts local law in the area of solar farms. This could leave many local regulations without teeth.

On February 2, 2017, the Maryland General Assembly, through gubernatorial veto override, passed legislation to increase Maryland’s renewable energy goals to 25 percent in 2020. Acts 2017, c. 1, § 5, eff. Oct. 1, 2016. Subsequently, Maryland implemented a “community solar” pilot project, which will make solar energy available to all in-

quality of life issue for certain rural areas and residents. Press Release, Anne Arundel County, Anne Arundel County Announces Eight Month Industrial Solar Operations Ban (Dec. 3, 2017). The eight-month moratorium ended on August 30, 2018, with the Anne Arundel County Council’s introduction of Bill 89-18. Bill 89-18 imposes stricter zoning regulations on solar fields per the recommendations of the County’s Agriculture, Agritourism, and Farming Commission.

Caroline County lifted its six-month moratorium on solar fields on December 12, 2017, through enactment of Ordinance #2017-2. Before that, Frederick County enacted a six-month moratorium by Executive Order No. 01-2016, effective January 15, 2016. On May 16, 2017, Frederick County adopted a solar facility commercial floating zone district (the “Floating Zone”) for the use of agricultural land for solar fields that requires a corresponding land use designation in the Comprehensive Plan. Frederick County Code § 1-19-10.700. After the expiration of Frederick County’s moratorium, the Baltimore County Council enacted its

agricultural land are not allowed by right, but rather pursuant to either a special exception (conditional use) or other zoning application, such as the Floating Zone. Anne Arundel County Bill No. 89-18; Caroline County § 175-13; Baltimore County Code § 4E-102(A); Wicomico County Code § 255-155B(2); Dorchester County Code § 155-50(LL); Cecil County Code § 54.4; Frederick County Code § 1-1910.700. The resulting zoning standards in these counties restrict solar fields on agricultural land in various ways by including, for instance, provisions for:

• A limit on the amount of prime agricultural soils that can be disturbed for solar projects. Anne Arundel County Bill No. 89-18; Frederick County Code § 1-1910.700(C)(4).

• A cap on the total acreage available for solar farms in the county. Caroline County Code § 175-85(A)(1). (Caroline County recently reduced the 3,000 acres of the County that can be used for solar farms to 2,000 acres. Id.)

• A cap on the number of facilities within each council district. Baltimore County Code § 4E-102(B) (4). (Only 10 solar farms, at any one time, are permitted in each council district. Id.)

come levels through a subscription to a single solar farm. COMAR 20.62.01, et seq. As a result, solar farms (utility scale and community) continue to be developed in rapid succession.

Many counties have imposed moratoriums on construction of solar farms in order to strengthen their zoning restrictions to strike a balance between what some perceive as competing public interests. Anne Arundel County most recently enacted a moratorium to halt the use of agricultural land for solar fields, framing the problem as a

own moratorium via Bill No. 68-16, which was vetoed by the late County Executive Kevin Kamenetz. Notwithstanding, the Baltimore County Council adopted amendments to its solar farm zoning regulations. Currently, Somerset County is in the process of amending its solar ordinance.

An underlying theme of the resulting zoning amendments adopted or proposed by the above counties and the zoning provisions already in place within some of the remaining Maryland counties is that solar fields on

• A cap on lot coverage or net area of the site used for the solar field. Anne Arundel County Bill No. 89-18; Frederick County Code § 1-19-10.700(C)(5).

• Prevention of the development within environmental features, such as environmentally sensitive areas, animal habitats, planned greenways and require forest conservation law compliance or other limitations on tree removal. Anne Arundel County Bill No. 89-18; Caroline County Code §§ 175-85(A)(4) and (B) (2); Baltimore County Code § 4E-104(A)(10); Frederick County

November 2018 20 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL

The increased use of agricultural land for utility scale solar generation facilities (solar fields that generate power for sale) has many Maryland counties struggling with how to balance two public interests – renewable energy and farmland.

Many counties have imposed moratoriums on construction of solar farms in order to strengthen their zoning restrictions to strike a balance between what some perceive as competing public interests.

Code § 1-19-10.700(C)(7).

• Imposition of buffer and screening requirements, including fencing. Anne Arundel County Bill No. 89-18; Baltimore County Code §§ 4E-104(A)(6) and (7); Dorchester County Code § 15550(LL)(1)(e) and (k).

• Protection of viewsheds, agricultural, conservation and historic preservation easements. Anne Arundel County Bill No. 89-18; Caroline County Code § 175-85(A)(3), §§ 175-85(B)(1) and (4); Baltimore County Code §§ 4E-104(A)(1)-(5); Frederick County Code § 1-19-10.700(B)(4); Dorchester County Code § 15550(LL)(1)(g).

• Regulation of glare and visible light. Anne Arundel County Bill No. 89-18; Caroline County Code §§ 175-85(B)(6) and (7); Baltimore County Code § 4E-104(A)(8); Dorchester County Code §§ 15550(LL)(1)(a) and (d).

• Imposition of a decommissioning plan, with a decommissioning bond/security, or other solar panel and infrastructure removal requirements. Anne Arundel County Bill No. 89-18; Caroline County Code § 175-85(C); Baltimore County Code § 4E-107; Frederick County Code § 1-1910.700(C)(10); Dorchester County Code § 155-50(LL)(1)(l).

• Imposition minimum distances between commercial solar projects. Anne Arundel County Bill No. 89-18.

Some counties prefer not to strike a balance, but to prohibit solar farms altogether on agricultural land. For example, Montgomery County has 90,000 acres of land in its agricultural reserve and allows solar only as an accessory use on that land (i.e., free-standing solar array must produce a maximum of 120 percent of the on-site consumption). Montgomery County Code § 59.3.7.2.B.1.

Despite these local efforts, the Maryland Public Service Commission (PSC) has jurisdiction to approve solar fields through the certificate of public conve-

nience and necessity (CPCN) process. Public Utility Article (PUA) § 7-207(b) (1)(i). It is recognized in certain instances that the CPCN process preempts the local zoning processes. The seminal case, Howard County v. PEPCO., 319 Md. 511 (1990), held that State law impliedly preempted local law in the field of public utility service. Specifically, the Court of Appeals held that State law preempted the Montgomery County Zoning Ordinance special exception requirements governing the location of power lines in excess of 69,000 volts because the State granted the PSC broad powers in this field and the State law gave no controlling deference or approval rights to the local jurisdiction. The State law merely provided for the PSC to give “due consideration to the recommendations of such bodies.” Id. at 526.

The “due consideration” standard is still applicable today. PUA § 7-207(e) (1) provides for “due consideration” of “the recommendation of the governing body of each county or municipal corporation in which any portion of the construction of the generating station…is proposed to be located.”

However, in 2017, H.D. 1350, 2017 Leg., 437th Sess. (Md. 2017) and S. 851, 2017 Leg., 437th Sess. (Md. 2017) added two additional criteria to which the PSC must give “due consideration”:

(1) the consistency of the application with the comprehensive plan and zoning or each county or municipal corporation where any portion of the generating station is proposed to be located” and; (2) “the efforts to resolve any issues presented by a county or municipal corporation where any portion of the generating station is proposed to be located.” PUA § 7-207(e)

(3). This triggered some counties to question whether preemption of local zoning was still the case.

The PSC’s public utility law judge (“PULJ”) relied on the State’s implied preemption of local regulations in the field of solar generation facilities when it initially approved the LeGore Bridge Solar Center, LLC’s application for a 20 megawatt solar field on agricultural land in Frederick County.

Proposed Order, P.S.C. Case No. 9429, 44-46 (Oct. 3, 2017). LeGore obtained special exception approval from Frederick County for its solar field prior to consideration of its CPCN application and Frederick County’s replacement of the solar farm special exception process with the piecemeal Floating Zone process. Id. At the close of the CPCN record, Frederick County filed with the PULJ a copy of the Floating Zone legislation to advance the notion that LeGore’s special exception was no longer valid and that it had to obtain Floating Zone approval. Id. at 33. The PULJ held in its Proposed Order that State law preempted Frederick County’s local zoning restrictions and alternatively, LeGore had obtained a special exception, and the special exception approval included a finding of conformance with the Comprehensive Plan. Id. at 46.

Frederick County appealed the Proposed Order to the PSC on multiple grounds. Notice of Appeal, P.S.C. Case No. 9429, 44-46 (Nov. 1, 2017). It argued against preemption on the basis of the recently enacted § 7-207(e) (3), Pub. Util., Md. Ann. Code, which added due consideration be given to the local jurisdictions’ Comprehensive Plan and zoning, thereby creating “complementary roles in the process” for the County and State. Frederick County, Maryland’s Memorandum of Appeal, P.S.C. Case No. 9429, 9 (Nov. 9, 2017). Frederick County also argued that the holding in HowardCounty was limited to public service companies, which LeGore was not. Id.

Without addressing preemption, the PSC upheld the Proposed Order on alternative grounds. In re: LeGore Bridge Solar Center, LLC, 2018 WL 1586448 (Md.P.S.C). It concluded that LeGore had vested its special exception and due process prevented the PSC from requiring LeGore to undergo the floating zone process so late in the game. Id. The PSC’s dissenting opinion argued that “due consideration” equates to “considerable weight” and by overlooking Frederick County’s comprehensive plan recommendations and Floating Zone, the PSC was deviating

November 2018 21 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL

from its normal practice. Id. The dissenting opinion also rebuffed LeGore’s reliance on preemption when it specifically mentions LeGore’s strategy to continue with the special exception process when faced with a moratorium and Frederick County’s proposed Floating Zone legislation. Id

Although the PSC declined to approve LeGore’s CPCN on the basis of preemption, the Court of Special Appeals recently addressed preemption in an unreported opinion. On August 28, 2018, the Court of Special Appeals issued unreported opinion, Board of County Commn. of Washington County v. Perennial Solar, LLC, 2018 WL 4090873, that upheld the issuance of a CPCN for a solar farm on the basis that local zoning regulations are preempted by State law and the applicant, although not a public utility company, was governed by the PSC because it was a “person” under PUA § 7-207(b)(1)(i) over which the PSC has jurisdiction to issue a CPCN. However, the CPCN at issue was subject to PUA § 7-207(e) before the amendments enacted by H.D. 1350, 2017 Leg., 437th Sess. (Md. 2017) and S. 851, 2017 Leg., 437th Sess. (Md. 2017). Accordingly, the viability of preemption by State law of local zoning requirements and Comprehensive Plan recommendations appears to be uncertain at this time, absent a subsequent decision by a PULJ, PSC, or Maryland appellate court.

Thus, preemption by State law may continue to be challenged by the local jurisdictions. However, the counties will likely continue to establish more stringent solar field zoning regulations and adopt Comprehensive Plans touching on solar field locations, in an attempt to preserve farmland – all balanced against the CPCN process.

Ms. Cirner is an associate in the Rockville offices of Miles & Stockbridge P.C.

Disclaimer: This article is for general information and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice for any particular matter. It is not intended to and does not create any attorney-client relationship. The opinions expressed and any legal positions asserted in the article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or positions of Miles & Stockbridge, its other lawyers, or the Maryland State Bar Association.

LEGAL CAPITAL, 4thEd

Legal Capital is widely credited with pioneering the introduction of the balance sheet and equity solvency tests, as well as other reforms in the Model Business Corporation Act and corporation statutes in over 30 states. This edition adds new historical material, updates the statutes and caselaw on dividends and other distributions in the U.S., and compares the evolution of legal capital in countries around the world.

“Legal Capital turns on a basic tension around the corporate form — how the concept of limited liability can place creditors’ and shareholders’ interests at odds, and how that tension isresolved through statute, case law, and private contracting. It is a must-read for corporate law students, academics, and practitioners, and a must-have for law firm and university libraries.”

Charles K. Whitehead Myron C. Taylor Alumni Professor of Business Law Cornell Law School

November 2018 22 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL

Visit | store.westacademic.com Call | 800-782-1272 email | inquiries@westacademic.com © 2018 LEG, Inc. d/b/a West Academic Publishing 101409 lb/6.18 West, West Academic Publishing, and West Academic are trademarks of West Publishing Corporation, used under license.

9781599417721

Bayless Manning, Late Former Dean, Stanford Law School James J. Hanks, Jr., Partner, Venable LLP, Baltimore

MARYLAND CHAPTER

The following attorneys are recognized for Excellence in the field of Alternative Dispute Resolution

The following attorneys are recognized for Excellence in the field of Alternative Dispute Resolution

Check preferred available dates or schedule appointments online directly with Maryland’s top neutrals

www.MDMediators.org is funded by these members

Check preferred available dates or schedule appointments online directly with Maryland’s top neutrals www.MDMediators.org is funded by these members

Sean Rogers Leonardtown

Hon. Steven Platt Annapolis

Richard Sothoron Upper Marlboro

Snowden Stanley Baltimore James Wilson Rockville

Hon. Monty Ahalt Annapolis

Jonathan Marks Bethesda

Daniel Dozier Bethesda

Douglas Bregman Bethesda

Hon. Carol Smith Timonium Scott Sonntag Columbia

Sean Rogers Leonardtown

Hon. Steven Platt Annapolis

Richard Sothoron Upper Marlboro

Snowden Stanley Baltimore James Wilson Rockville

Hon. Monty Ahalt Annapolis

Jonathan Marks Bethesda

Daniel Dozier Bethesda

Douglas Bregman Bethesda

Hon. Carol Smith Timonium Scott Sonntag Columbia

NADN is a proud sponsor of the national trial

bar associations... To visit our free National Directory of litigator-rated neutrals, please visit www.NADN.org

John Greer Simpsonville

and defense

Peculiar Problems with Variance Ordinances

By Derek M. Van De Walle

In this article, I am not talking about variances in critical areas, nor do I discuss use variances in any in-depth respect.

When reviewing a grant or denial of a variance, the court will “look first to the words of the applicable statute, ordinance, or regulation to divine what the enabler intended the weight to be accorded by the ultimate decision-maker to a recommendation of the plan.” Richmarr Holly Hills, Inc. v. American PCS, L.P., 177 Md. App. 607, 636 (1997). Due to the manner in which local ordinances and regulations are worded, this process requires the occasional divination by the court. Although generally applicable criteria and standards exist for reviewing variance applications, these criteria and standards are often rendered inapplicable due to the wording of the ordinance itself. Exacerbating this problem is that no two variance ordinances in Maryland are alike, with the language varying among each of the twenty-four counties. The differences range from how a variance is defined to the standards applied when granting or denying a variance application. While local zoning authorities and land use practitioners may be familiar with the nuanced differences in variance ordinances, often, the average applicant is not. Two continuing sources of confusion for members of the public in variance construction are discussed below: the meaning of the “unique” requirement and the use of conjunctives or disjunctives for the practical difficulties and unnecessary-hardship tests. This article highlights this confusion and discusses how, in recent years, Maryland courts have attempt-

ed to thwart the problems they create.

The Difference (or Lack Thereof) Between “Peculiar” and “Unique”

One of the many criteria that are required for a variance application to be granted is that the property in question must be “unique.” A property is considered “unique” when it has inherent characteristic not shared by other properties in the area, i.e., its shape, topography, subsurface condition, environmental factors, historical significance, access or non-access to navigable waters, practical restrictions imposed by abutting properties (such as obstructions) or other similar restrictions. Cromwell v. Ward, 102 Md. App. 691, 710 (1995).

The Land Use Article, however, does not use the term “unique.” Instead, “peculiar” is used in its place: “and where, owing to conditions peculiar to the property and not because of any action taken by the applicant, a literal enforcement of the zoning law would result in unnecessary hardship or practical difficulty, as specified in the zoning law.” LU § 1-101(s) (emphasis added).

Many Maryland counties – for example, Calvert, Carroll, Cecil, Dorchester, Frederick, Saint Mary’s, and Wicomico – follow suit and use “peculiar” in their ordinances to define “variance.”

Other counties – such as Caroline, Montgomery, and Queen Anne’s –include “peculiar” when discussing the standards for variances. Somerset and Garrett Counties do both, and Allegany and Washington Counties do

neither. Calvert and Prince George’s Counties use “peculiar” and “unusual” when describing “practical difficulties” and “unnecessary hardships” in their standards. Charles County does this as well, but also requires that any special conditions on the property be “unique” to the property. Worcester County uses “special or unique” to describe how the conditions of the property must be. Talbot County uses solely “unique” in its standards. Baltimore City and Kent Counties set the threshold even higher by requiring that the special conditions be “extraordinary.”

Generally, “peculiar” means something that is strange or unusual, while “unique” means something that is “one of a kind.” But in the context of variance cases, they are synonymous with one another. However, this has not always been clear. Cromwell v. Ward, 102 Md. App. 691 (1995), could be read to imply that “peculiar” and “unique” are separate standards. This is most likely due to the fact that the appellant presented it as such. Basing his argument on the Baltimore County Zoning Ordinance, the appellant argued that the restrictions of the applicable ordinance “taken in conjunction with the unique circumstances affecting the property,” must be the cause of the hardship (emphasis the court’s), and that the variance could only be granted where special circumstances or conditions exist that are peculiar to the land or structure which is the subject of the variance request . . . .” Id. at 694 (emphasis the court’s). The Cromwell court held that the law in Maryland “has always been a property’s peculiar characteristic or unusual circumstances relating only and uniquely to that

November 2018 24 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL

property must exist in conjunction with the ordinance’s more severe impact on the specific property because of the property’s uniqueness . . . .” Id. at 721 (emphasis added). The use of the disjunctive “or” would seem to imply that there is a difference between “peculiar” and “unusual” as they are used to modify “characteristic” and “circumstances,” respectively; at other times, the court appeared to use the terms interchangeably. Regardless, the distinction between “peculiar” and “unique” was not at issue in the Cromwell case, and so the court would have seen no reason to address it.

In 2017, the Court of Special Appeals sought to correct this problem by erasing any distinctions among “peculiar,” “unique,” and “unusual” in Dan’s Mountain Wind Force, LLC v. Allegany County Board of Zoning Appeals, 236 Md. App. 483 (2018). Allegany County, a home-rule county, does not provide any standards for reviewing variance applications. Instead, variances are mentioned only in the “definitions” section. The Allegany County Code, at section 360-59(A)(1), defines a zoning variance as a:

change of density, bulk[,] or area requirements, with respect to the loca-

tion of a building or a use on a lot of record, where the physical or natural character of the lot would otherwise preclude the use of the lot.

As noted above, this definition includes neither the word “peculiar,” seen in most definitions of “variance” in Maryland counties, nor the word “unique.” With no standards in the ordinance to rely on, the court implemented the general two-part standard “to determine whether a variance should be granted in a particular case.” Dan’s Mountain, 236 Md. App. at 491. The first part is the “uniqueness” test. Id. at 492. In applying the test, the court acknowledged that “Maryland cases have used the terms ‘unique,’ ‘unusual,’ and ‘peculiar’ to describe this step in the variance analysis.” The court asserted that “[w]e made clear in Cromwell that these words are used more or less interchangeably to mean ‘unusual.’” Id. at 494 (citing Cromwell, 102 Md. App. at 703). Whether the Cromwell case in fact does this is debatable, but Dan’s Mountain effectively ends that debate with its decisive language. And by doing so, Dan’s Mountain makes it clear that the differing use of “unusual,” “unique,” or “peculiar,” throughout the 24 county or-

dinances means nothing because they are one and the same concept.

Using Conjunctive and Disjunctive Terms for the Practical Difficulties and Unnecessary Hardship Standards

Variances fall into two categories: area variances, providing variances from area, height, density, and setback restrictions; and use variances, permitting a use other than that permitted in the particular district by the ordinance. See Dan’s Mountain, 236 Md. App. at 501. Maryland permits only area variances. See LU § 1-101(s) (“‘Variance’ means a modification only of density, bulk, dimensional, or area requirements in the zoning law that is not contrary to the public interest . . . .”) (emphasis added).

Area and use variances, theoretically, require different standards. The less stringent “practical difficulty” test applies to area variances, while use variances, because they could potentially change the nature of the neighborhood, face the “unnecessary hardship” or “unwarranted hardship”

November 2018 25 MARYLAND BAR JOURNAL