Workshop and short manual

Maša Ogrin, Nina Vidić Ivančič

Maša Ogrin, Nina Vidić Ivančič

Thatch roofing

Workshop and short manual

Gornji Petrovci and Ljubljana, 2022Introduction

Maša Ogrin, mag. inž. arh.

Straw, as a building material, considered in the context of roofing, stirs up a reflection on how we use the resources and raises the question of how much we know about old traditional construction practices.

The topic of the project brings up questions in various fields. What is the source of construction materials? What is its production cycle? How to actually handle the material required for construction? How does everyone who participate in creating and constructing a house collaborate? The topic also examines the possibilities of making such roofing in the modern age. It raises a question of whether we are even allowed to use home-made materials.

Ultimately, it also poses an entirely technical question of how to build a roof, one of the essential elements of a house?

Architectural production today dictates a tempo that does not allow for a masterful command of crafts, while it simultaneously makes us dependent on the external market by discouraging use of our own resources.

The aim of this publication is to shed light on the still living knowledge about thatch roofing and share it in an environment where it will be available to many who are interested in it. Possibly, this knowledge will be very valuable to us in the future.

By combining knowledge, lecturers, masters, participants, students who enthusiastically attended the workshop, architects who are already applying their skills in practice, and individuals who wish to build their homes in this manner, the project resulted in a lively debate that carries the lore into the future.

Thatch Roofing

Past and present

About thatch roofing in the lives of Slovenians

Conversation with ethnologist Jelka PšajdLet’s begin at the beginning. How do we produce thatching straw?

Straw is a by-product during harvest. In this region, wheat prevailed in the fields. The best grain for thatching was, howev er, a wheat-like cereal plant, i.e. rye, with stems reaching up to 70cm and of suita ble quality. There was a manual procedure to treat straw for thatching and each year people prepared some of the sheaves for regular thatch-ing or, in other words, for repairing a thatched roof. It was believed that a well-thatched roof could last up to 30 years. It could indeed; but one has to take into account that a roof of such age was repaired almost every year. This is why it lasted so long.

others, they used splints. The simplest way to achieve this, however, was to just cut grooves into a smooth surface with an axe.

What is the origin of these skills?

This is our heritage. And by this I mean that the materials were taken from the environment where people lived. In this geographical area, the construction of liv ing spaces from natural materials (clay, straw/cane, wood) traces its roots back to prehistoric times and the same materials were still used in the first half of the 20th century to build the traditional Pannonian log cabin cimprač. Having knowledge about the natural materials and their use as well as construction skills, all this is old heritage.

Was the process of threshing wheat any different for straw intended for thatching?

During manual processing, special at tention was paid to the stems to cause them the least damage. During the process of separating grain from stem, good stems were retained and tied together into sheaves.

In the past, thatching roofs with straw was inexpensive, because the material was sourced from nature. To put it in simple terms, there was no other, cheaper option. Today, however, a previously necessary skill is turning into a boutique option. Also and mostly because it is rare! Everyone used to have straw and almost everyone had to know how to thatch; if nothing else,

Within the scope of the Thatched Roof Project, we would like to highlight the importance of straw as a building ma-terial in Slovenian history, particularly that of the Pomurje region. We would like to know how this material is con-nected with the environment where it is used and how it is woven into folklore.

What remained was used either for cattle bedding or cut with a chaff-cutter and used as food supplement for cattle, or the cut remnants of stems were added to clay for plastering (as a binder). Plaster does not really stick to a straight (wooden) surface, so various tricks and skills must be used and these hark back to folk knowledge and expe-rience of our fore bears. For the plaster to harden well onto wood, a smooth surface had to be roughed. In certain places, they used cane sticks, which were fixed onto a wooden wall, in

at least how to patch a roof. The men I have in mind were jacks-of-all-trades who were skilled in various home crafts, partly because they lived in modest conditions and had to learn them. If people did not know how to do something, they asked their neighbour. This was not just mutual help, but also an exchange of work and skills, an exchange of favours. I would like to underline here that women and housewives were very skilled at preparing the clay and plastering wooden walls with it. Frequently, women were the ones who decorated the white limewash on the exterior façade.

Was thatch roofing a specialized skill?

Thatch roofing entailed knowledge and skills that required experience. One had to know how to properly prepare the material: how to harvest a cereal, treat the stem manually (separate grain from the stem) and store straw. These are the skills required to prepare straw. A spe cial skill was needed to thatch a roof: what is a suitable thatch thickness, how to secure sheaves to the wooden part of roofing, how to finish ridges on a thatched roof and so forth. Such work requires specialised tools, for example a short ladder (called hlapec) and other tools made at home. The material for securing straw onto roofing was also important: slender willow rods (called pintovec) had to be cut, stored and prepared at the right time so that they would be flexible enough and not break during fixing. This also was an impor tant skill! Later, they started to use wire but even though it was easier and faster to fix straw with it, it could also damage the straw.

Why is straw important for the Sloveni an countryside?

In the countryside, the use of straw was a way of life. Not a single part of it would go to waste (it was used as construction material, as a food supplement when there was no other fodder for cattle, and as manure). Another aspect was also

painful. Threshing in a steady beat also involved onomatopoeia or, to rephrase it, creating a pleasant beat and sound.

And, as I mentioned, people today mainly remember large thresher machines, especially a locomobile, a metal device that propelled a wooden thresher, which was also called a mašin or danfar. It had

What are stooks?

A stook is a stack of 18-21 sheaves of grain. They were stood in a field to dry.

The top sheave is called pop (meant as a tax for the priest and collected every year in a village, also known as a church due (cerkvena zbirca); it was placed with spears turned downward to prevent standing water in case of rain and enable its run off.

Was threshing done at a specific time of the year?

Feast after threshing

work carried out in connection with straw, one of by-products of cereals. What I have in mind is harvest, especial ly threshing, which required a special type of work – joint work.

Why were machine threshers important for the community?

What people from the Pomurje region most remember today are the machine threshers. But before people started using these machines, they threshed manually, with flails, which required rhythmical threshing. If threshers, work ing in twos or fours, failed to follow the beat, the whole affair could become very

to be controlled by a trained machine operator. This manner of threshing required from 18 to 22 workers and that shows the scale and importance of mutual help between villagers. The machine threshers used to go from house to house in the village and the machine operator received the highest pay for his work. The remaining workers, if they were hired and were not helping in the spirit of mutual favours, received grain as pay, while during harvest they received sheaves which were harvested and put into stooks.

The threshing period came after har vest. For a thresher, that meant that he threshed from one to two months a year –depending on the amount of crops and number of clients. As I mentioned, the thresher received the highest payment and also the best food. He had to fuel the engine and issue orders out to others. This was an organised sys-tem of 18 to 24 people. Everyone knew who filled the machine at one end and who held a sack under it at the other. Let us not forget the housewives who prepared hearty meals. Vrtanek, a round, braided bread with a hole in the middle, played an especially important role.

Is there a specific custom related to the process of producing grain?

Of course, there are many, bread was a staple that had a symbolic role in the life of an individual and the commu nity and it also signified sufficiency. A very important custom that is no longer practised today, also due to the technique of making, was a garland of wheat called doužnjek, crown, wreath of grain or St. Peter’s beard. From the last harvested sheaf

(doužnjek means the last one during har vest) a wreath was made, a flower or two was added and then it was taken to the landlady or landlord in the spirit of cele bration. In exchange, workers were served with vine or vrtanek (a specific type of bread) and ate to their heart’s content. The householder placed the wreath on a prominent spot because it was believed to be good luck. This is an old custom and it is assumed that, in the begin-ning, they left the wreath in the field as an offer ing to a deity. One way or the other, this custom embodies a re-spectful attitude towards nature.

they had the chance, took up season al work to earn money. This is the flip side of this idealized life. They had to try their luck abroad to earn their living and they had to go to large properties in Hungary, Bačka or Banat, to do season al harvest or other types of field work. After a few months of work, they brought home sacks of grain by train to sustain them for the winter.

Did the emergence of machine threshers have any impact on the intercon nectedness of people?

Not yet, the machine thresher, as men tioned, still required the cooperation and assistance of 18-22 people. I would like to call attention to the fact that this type of work demanded solidarity, help and co operation. Individuals de-pended on each other, on their neighbours and family.

In his book Praznično leto Slovencev (Slovenian holidays throughout the year), Niko Kuret describes that, even though they worked hard, they were also bantering or played tricks on each other... They did. They had a mischievous streak, it sprang from their socializing, their way of life... This mutual help and work was often also an opportunity to meet a future husband or wife. People and their everyday tasks were linked to their micro environment, to a close-knit countryside community. In the period between the two great wars, people, if

Farms were small. Particularly in Goričko, where there was little fertile soil. During winter, people stayed at home and lived off earned grain. They used it (its flour actually) to cook and bake, or sold it if they had a surplus of it, and then again ventured into the world to find work. This is the other side of a happy, content life in a village or a countryside; in reality, it was daily grind and a hand-to-mouth existence.

The work was hard, while customs or entertainment were something that accompanied all this hard work. Customs often also marked the start of work, usually with a prayer for the work to go well. It was customary that a landlord, before he went to plough the land (perhaps it was similar for

harvest), made a cross in front of the cows. “Praise God for good harvest.” We should not interpret this only in the strict Christian sense, but rather in a wider context. Wishes and prayers did not refer only to God with a capital let ter. For example, people also prayed be fore a meal. Not only to God but mostly to weather, so it would not destroy the crops. They were aware of their dependen-cy on weather; therefore, they thanked nature and, in some way, also themselves for the work carried out and for their health that enabled them to do physical labour. Nowadays, we no longer respect physical labour, weather and prayer, because we naively think that we can get everything in shopping centres. This is why respect towards many things and many people is passing into oblivion. The people I have in mind are farmers who remain on their land and farms in hilly and mountainous regions and who deserve the respect of national agricultural and economic apparatus, as well as the re spect of us, individuals, who would like to buy boutique products at the same price as those grown and produced in the lowlands, where work in the field and production are substantially easi er, faster and simpler. And, more often than not, also of poorer quality!

reality is different. If you ask me, you will be hard pressed to convince a big farmer (a cultivator of crops or a cattleman who has experience with producing and processing straw) to work with straw be cause he earns good money with selling milk and cattle. And then there are also subsidies and grants which guarantee a good, quality life to big farmers (virtually half-industrialised and robotised farms and robotised farm work). At the mo ment, the process of producing quality straw is expensive, because it involves more manual labour than machine work and there are not many people who want to do this kind of work. Simply put – it doesn’t pay. Because manual labour is valued so poorly, no one sees the op portunities in working with straw and natural materials. On the other hand, it is a mockery that this type of work and materials are so rare that they are becoming precious or too expensive for an established and widespread use in contemporary construction.

Today, also taking into account the response to the Thatched Roof work shop, we can sense a desire to return to traditional techniques and to respect the environment we live in. This is how I will answer your question: Boug daj toj rejči hasek. [So be it]. The

Examples of such practices, like yours, can hint at the possibility that they are indeed worthwhile. And when this will be reflected in the market, there will be more opportunities to return to traditional skills, manual work and natural materials. As a modern society, we must want and strive to finally grasp the meaning of tradition and natural living. Now it revolves merely around individuals trying to do no wrong and to not harm the environment. I think that this kind of attitude is a necessity and an indispensable ecological advantage, therefore it should be supported in any way possible.

Anton Golnar

Interview with a master thatcher

Your work is not easy. What convinced you to continue?

To be an independent craftsman is something entirely different than being someone’s hired hand. The biggest issues were with the materials, which I had to prepare myself. At the beginning, we could still buy around a ton of straw, but later almost all other farmers aban doned this activity. Older people used to do it, younger generations stopped doing it and we had to start harvesting cereals in the fields ourselves. So, we used to buy existing rye from farmers, we harvested, cleaned and stored it... Today there is virtually no rye to be bought, so we started growing it in our own fields and also leased ones. Now we also sow and plough up to 15 hectares: mostly rye, some wheat (a longer variety) and one third spelt.

Did you work on your own from the start or were you joined by anyone else very early on to help you out?

I had one occasional worker who helped me prepare straw. Then my son, when still in elementary school and then as a first-year high-school student, started thatching roofs. He learned the ropes so quickly it surprised me, because after only two months, he started to improve on my own work. (laughter)

What will be his challenges in the future?

Ah, yes, challenges. In 20 years, I covered 1000m2 per year. He is now already re-thatching roofs that I thatched in the past. If all of these will be repaired and if he also thatches some new roofs, he will have to work a lot, grind away. If his son will join him soon, as he joined me, then it will perhaps be smooth sailing. Or if any other thatchers crop up.

What’s your story, how did you start thatching?

My interest was roused when I was unemployed and I already had some skills because I previously attended a course organized by the Gornja Radgo na Community College. This was in 1987. I had no job for a few years, so I decided to go for it because it seemed that there would be work with thatched roofs. The first project was an open-air museum in Rogatec; this is when I got self-employed, initially in the form of an additional activity on a farm, because we have a small farm at home. The word about our work spread everywhere. To all the mu seums in Slovenia and also to heritage-protected buildings where they recognized what we were doing, so we always had enough work.

Does your grandson already show some interest? Will the family tradition continue?

My grandson likes to join in any work and even though he is only ten, he likes to climb onto a tractor and it is obvious he really takes pleasure in the work on the farm. Let’s hope he’ll join his father and continue to work with straw.

How could we familiarize people with the material or generate interest?

How much do people even know about thatch roofing?

Yes, well, it is often the case that people haven’t got a clue about thatched roofs, except that they see it looks nice. They also need to be told beforehand about the downsides of a thatched roof. There are several thatchings. The Hungarians do it in their own way and with cane.

which grew up to 1.8 metres. It vanished completely; four years ago, we got 100 grains for 100 Euro. This one really is a little taller, but not as tall as spelt. The grain of this wheat, however, is easier to use, at least for the animals; spelt has to be hulled if you want to make bread or something similar.

We are one of the rare ones in Slove nia who thatch with straw and we also produce it ourselves. It has to be noted that straw has to be clean, without grain, and that it has to be placed at the right pitch. The right angle of the slope poses the biggest issues because sometimes an architect is unable to draw any other pitch than a 32 degree one. (laughter)

How widely is straw used in modern times?

Mainly, it’s used as thatch on public fa cilities, museums. There are also private structures, but there aren’t many. There are some houses that were thatched by their owners, but I could not say that it is widely used.

You said that you are one of the rare ones who use straw for thatching; other materials are already being used in other places, such as cane. How do these two materials compare?

Ah, yes, the materials ... These materials do not grow here. Because here, anyone who wants to thatch a roof does it with straw, but Hungarian master thatchers also come here and bring cane with them. As the prices go, they are more or less the same now.

How much straw do we need for 100m2 of roof?

For 100m2 of thatched roof we need two tons of straw.

How much work is involved in prepa ration as opposed to actual work on site?

Compared to thatching, preparation definitely takes three times longer.

Let us look at the actual numbers; how many hectares of straw and what kind do you produce?

This year, we have 13 hectares: there are four hectares of spelt, the rest is rye. We have roughly half a hectare of wheat, an English variety, because today it is very difficult to find old wheat, the tall one,

What is the price of brick roofing compared to thatch roofing?

Thatch roofing is more expensive due to all the work involved. It is 50% more ex pensive for sure, but that also depends on other types of roofing since their prices vary.

The future looks increasingly more uncertain, environmental and economic challenges are becoming ever greater, there are many imported materials.

What is the future of using straw for thatching roofs?

I do not think the number of thatched roofs will increase in the future. Those on buildings protected as monuments, on museums, they will endure. Whether people will continue to re-thatch and use the material or not is also a matter of income and individual choice.

it; one does not need to be as skilled as with thatching.

What is a thatcher’s most important tool?

The most important tool is the thatch er himself: that he has everything he needs at hand, the knowledge and experi-ence, he also has to have an eye for it. And he has to notice the thatch thickness, make sure it is even.

What is the difference between roofing with industrial materials and thatching?

There is a lot of work involved in pre paring the material for a thatched roof, the straw. Preparing it, this and that. With other materials you simply go to the store, buy the material and install

Would you like to share a story about your work?

In the old days, says one story, when... Well, not connected to my work, but there is an old anecdote, if you would like to hear it, about a thatched roof: This was when... there was draught and people ate all the grain. The old ladies already stored it away, said the young ones: “But we still have to go on, what of it.” And when the rain came, they had no more grain, not even any seeds, which they usually stored. And one of them went and secretly asked their father, the young ones do not know, right, they do not know everything, and then he went and asked his father: “What do I do now? We have no grain; we should be sowing.” His father said: “Go up on the roof, uncover it and for sure you will find a grain or two up there.”

*Record of the anecdote in dialect: Sabina Slankovič

Thatch Roofing

The workshop

Preparation of the structure for the workshop.

Preparation of the structure for the workshop.

Seamlessly tied together

Working with straw and the workshop experience

Author: Pia Gerbec, student of architecture

Our work with straw really began in the middle of the process that usually lasts around a year. It starts with sowing wheat in October, harvesting it at the end of June or the beginning of July, and then it has to be cleaned and stored.

A scent of freshly laden hayracks wafted through a modern barn, a golden carpet was rolled out on the floor; its even-ly interwoven threads waited for gentle hands to comb and clean them, sort them by size and tie into sheaves which in three days’ time will come together to create a thatched roof.

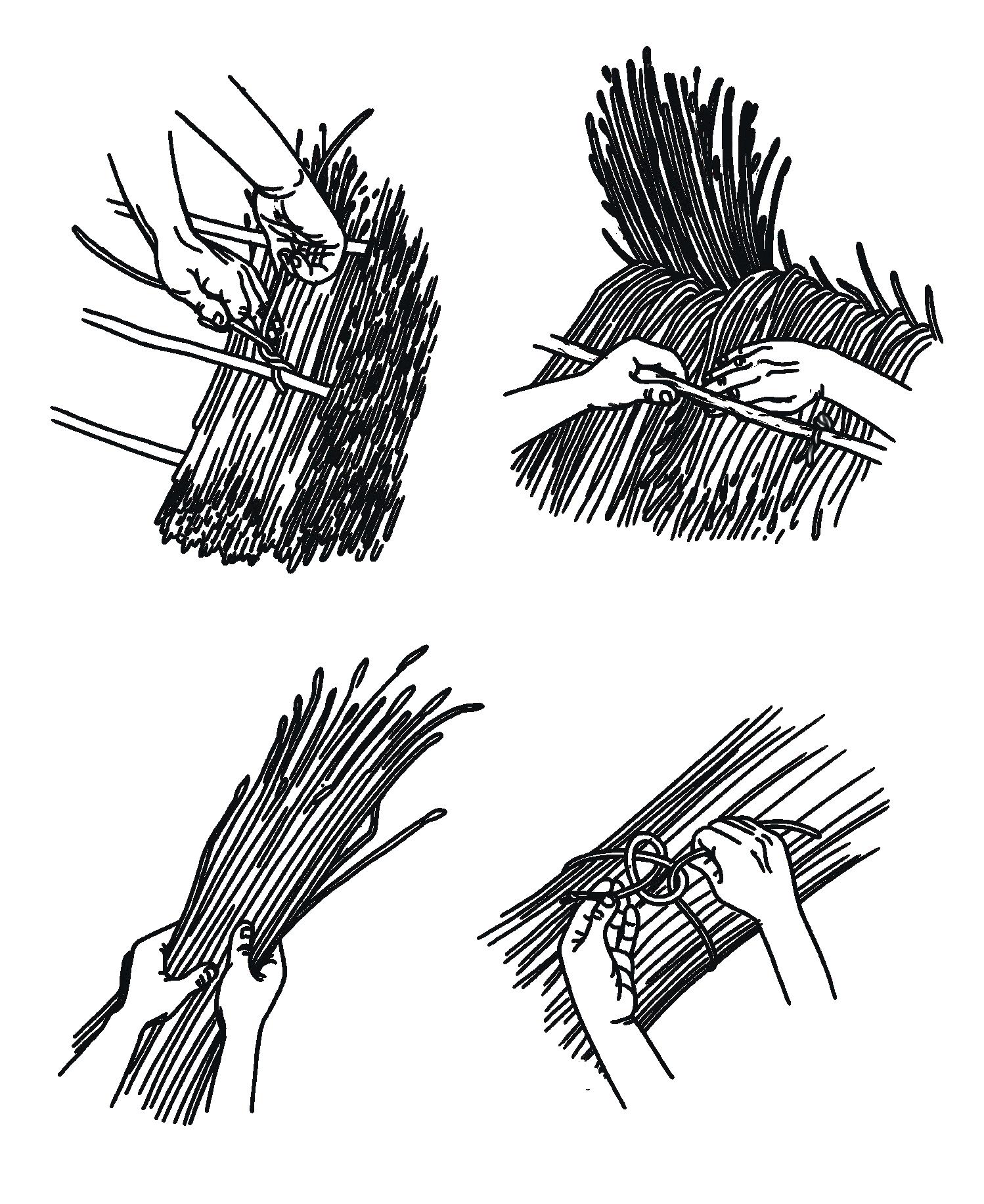

Straw is tied into carefully aligned smaller sheaves with a special knot that allows loosening.

We start thatching the roof from the bottom up, in rows approximately half a meter wide. We use hazel rods that are fixed onto the construction. Between these rods and the laths, the prepared sheaves of straw are secured. Hazel rods are additionally tied onto the construction with willow rods or, in modern times, wire so that straw wedged between a hazel rod and the wooden construction does not move.

“For me, building with straw was more like sewing than construction. Lacing together sheaves of straw, willow rods or ‘gožviceʼ and hazel rods. The gentleness of the material is woven into the process and also into the final product.”

14 The short ladder (“hlapec”) used on the roof

13 Placing of sheaves: shorter at the bottom, longer at the top

15 Composition of the roof

When the sheaves are spread out, we untie them so that the stems are evenly distributed, then we additionally secure them onto the construction.

We use a manual tightening tool called šponar. This process is repeated until we arrive at the ridge, then we again move to the bottom of the roof at the other side and start a new row. During thatching, we always use a prička, an implement to straighten straw from the bottom up and to spread it evenly across the roof surface. To work at heights, we can sometimes use a short ladder called hlapec

16 The tightening tool (“šponar”)

17 The aligning tool (“prička”)

“Rather than the traditional use of this technique, I find the approach to building and being more important: and working with straw, a natural material, has a lot to teach us about this. About a forgotten attitude towards mistakes, repairs and maintenance. We are increasingly lacking an attitude founded on our involvement in work, in the process, the creation. The attitude that makes us stop and think before discarding anything, that makes us repair and reuse. Because what makes something beautiful is that small part of us we put into it – our time, idea, will, strength and good company.”

Roof construction should have a steep pitch, at least 40 degrees or even 45 degrees, because it allows water to run off quickly after rain and straw to dry. It is best if a thatched structure is located in an open area and not in the shade of trees, because that could prolong the drying time.

Sheaves of straw used for the ridge must be longer so that they can be bent over to the other side of the roof; this is to prevent leaking. When we repeat thatching on the other side, a thatched roof is finished with a ridge.

“Work suddenly becomes a lot more – a space for exchanging ideas, advice, problems, for posing questions and receiving answers. This sets off the reciprocity of two processes – work promotes socializing and socializing inspires work. The latter thus stops being a chore but rather an opportunity to create, learn and connect.”

The

path into

the future

Examples of contemporary architecture

Museum and Biodiversity Research Centre

Guinée*Potin Architects

Completed: 2014

Location: La Roche-sur-Yon, France

Area: 2057m2

Client: Région des Pays de la Loire

Photo credits: Sergio

Grazia, W. BerréWhy did you decide to use the material?

In our studio, we take a keen interest in traditional materials and shapes. For us, a relationship between architec-ture and context is key; this is also aligned with environmental issues and explains our interest for the material, especially within the context of vernacular architecture.

We mainly build here in the west of France since it is the region we know best. Our projects are inextricably linked with the area, architecture, materials and the environment.

In a landscaped green environment, a project takes on a strong identity, reinter preting in a modern and innovative manner the traditional technique of thatched skin that envelops entirely the walls and roofs of a building. The com-petition pictures show a natural ageing of the material, the fading to grey hues and the changing of hues at the turning of seasons. The building organically blends into the environment, embracing Mr. Durand’s mansion without upsetting the natural order of things. Solid raw chestnut stilts interfere with the overall look of the project on pur-pose. The building resembles a branch laying on the ground, it is a ‘part of built environmentʼ, a ‘new

geographyʼ complementing the natural sce nography. If the building is raised up from the ground, the impact of foundation works is minimized and the biodiversity remains undisturbed. The project then takes us up a gradually ascending terrain and reveals a pond, a home to frogs and herons, while next to the entrance to the location there is an edu-cational greenhouse.

Is straw a traditional material in the region?

The thatched roof technique was some thing entirely ordinary in France before the 19th century, before new me-chanical tools were developed in agriculture. Af terwards, such roofs were preserved only in some parts of France: there are many thatched roofs in Normandy and there are some in Brittany and the Vendée region where the pro-ject is located.

Where was the straw sourced? How hard was it to find the material and why? How was the building process? Did you employ a specialized builder? What were the main challenges that you faced while working with the material: design/execution?

Thatched roofs are undergoing a revival within the context of aesthetic standards in France, especially in the vicinity of Nantes, in Brittany, more specifically in the Brière area. There are a few thatching businesses so it was not hard to find a contractor to construct the roof. The problem arose when it came to making the outer skin. French com-panies do not have the skills for work ing with this material on a vertical surface, so we had to find a company that was willing to learn. The entire team went to the Netherlands for a month to learn the technique. There, they do not use the traditional

technique of ‘sewingʼ individual sheaves onto a surface, but they rather use metal fastenings that fix sheaves onto a surface. This technique makes the ‘skinʼ denser and more resistant; the same technique is also used for the roof. The wooden walls and the construction are prefab ricated in a factory and assembled on site. The thatched skin is an entirely different story; one person covers 6m2 in a day. Here, 2000m2 had to be covered and it took us 10 months (consid ering that it was wintertime and that working conditions were hard).

Is there potential in using straw as a building material? What are the reasons that it is not used widely?

From an environmental perspective, straw is really interesting, especially if we take into account its insulation char-acteristics and the low environmental impact of its produc tion. Because it is compact, it does not quick ly become a breeding ground for insects. In the worst case scenario, moss starts growing on it but it does not damage the roof itself and it can take up to 30 years for the moss to cover the roof.

The Tåkern Visitor Center and Bird Sanctuary

Wingårdhs Architects

Completed: 2012

Location: Lake Mjölby, Sweden

Area: 1000m2

Client: Östergötland County Administrative Board

Photo credits: Åke Eson Lindman

Why did you decide to use the material?

The bird sanctuary Lake Tåkern is surrounded by reed. The lake is very shal low, and the reed must be cut down to keep the lake open. So the idea of using the material harvested next to the house came very naturally. Especially after we found out that the reed was sold to Denmark every year, where it was used to make roofs. For Tåkern we needed a whole year's »supply« of reed from the lake area and it takes one year to dry before it could be used.

Is straw a traditional material in the region?

Straw has traditionally been used everywhere where there is a need for a cheap and easy way of cladding. Reed, harvested from lakes and shores, are slightly more sturdy than straw (from oat or wheat) but wherever there was an abundance of material, people found a way to use it.

You can still find specialists on roof clad ding. We found people from Poland, where cladding with reed and straw is more common than in Sweden.

What were the main challenges that you faced while working with the material: design/execution?

How was the building process? Did you employ a specialized builder?

Cladding with reed or straw works better the more steep the roof is, for the best durability the steep should be at least 45 degrees. This affected the design and opened for a monolithic interpretation of the volume. Cladding can cover all edges and corners seamlessly. The only fragile part is the ridge – the top of the roof. The reed were therefore replaced by glass on the ridge. This gave the exhibition space inside a nice, top-lit solution.

Is there potential in using straw as a building material? What are the reasons that it is not used widely?

Even though the material is cheap, it takes a lot of work to create a sturdy and beautiful roof. It is expensive, it will need to be maintained or replaced more often than tiles, for example. But if the work is done properly, the material has long durability, approximately 50-70 years. One big problem is the number of contractors that have the skills to do the work and the short period when it's possible to do it. If we had used only Swedish spe cialists we would probably have had to employ almost everyone in Sweden to get the job done.

However, it does give the building a wonderful camouflage that is most appropriate in an environment where the focus is bird-watching.

Thatched Hut in the Austrian Alps – SkinOver

Armin Kammer, Anke Wollbrink, students of theseminar

Completed: 2019

Location: Alps, Austria, Vorarlberg

Area: 12m2

Client: University of Stuttgart

Photo credits: arhiv IBBTE

Why did you decide to use the material? It was a very formal approach in the beginning. We realized that in their design work for a mountain hut the students attempt ed to design the full envelope – facade, and roof – out of a single material to generate a monolithic design.

In the following student workshop, we researched materials that could be used in this way. Besides stone, concrete, wood, and metal we rediscovered the material –thatch – which allows a very three-dimen sional design, similar to concrete. This fascinated us right away and led to further research and the idea of building a proto type of this thatched envelope.

The objective was to research the ap propriateness of reed as a facade and roof cladding material, especially in high-alti tude alpine regions. Reed, also known as thatch, is in every sense a sustainable, renewable, carbon-neutral resource: rapid growth, short process chain with low energy demand and emissions, perfect life cycle, no pollutants, tested over generations. Au thorities in Vorarlberg have been very open to thatch as a material because it has been used over generations. Traditional crafts

manship is still blooming and highly ap preciated in this area. Another important aspect was the expected visual integration of reed after turning gray over the first years with the stone surrounding it.

Where was the straw sourced? How hard was it to find the material and why? The focus has been on reduced local materials and craftsmanship. After a lot of research, we got the information that near Vienna at NeusiedlerSee reed is being har vested again. The only area in Austria for now. The timberwork and the larch wood cladding have been harvested in local surrounding forests and manufactured by a local carpenter from Brand.

How was the building process? Did you employ a specialized builder?

Only the thatcher came from Germany. We could not find a local craftsman but we have been very lucky to connect with a group of craftsmen loving their pro fession and want to push boundaries by keeping old knowledge and tradition.

What were the main challenges that you faced while working with the material: design/execution?

The design needed to be simple and appropriate to location and purpose. The main focus was on the material itself and the coordination of its architectural and manual (technical) details. It was essential to include craftsmen in the early stage of planning to develop simple and appropriate details. A team of craftsmen, students and faculty staff developed and built the project together.

Because the covering was done in the Alps, the envelope of the building was done in local thatch and wood and the metal connections were thoughtful ly placed to reduce the amount of the material.

The dead-standing part of the plant is going to be replaced by a new plant every year. Only this dead part of the plant is going to be harvested and can be used as a cladding material for the facade and the roof without any further treatment. At the end of life, reed is compostable and closes the material life cycle.

But there are missing regulations for reed, its characteristics and qualities. Our research is ongoing – renewable resources need to be more visible in the construction environment. Right now we are researching what reed as a material can 'learn' from more established materials like wood and loam – especially in terms of regulations, prefabrication, etc.

Is there potential in using straw as a building material? What are the rea sons that it is not used widely?

We also researched contemporary thatch architecture and found beautiful strong examples in France, Denmark and Sweden.

We even found the first attempts of prefabricated thatched facades. Prefab rication has been the driving force for materials like wood and rammed earth to enter contemporary architecture.

Reed grows fast, forms a valuable bio tope, generates better water quality, and provides a home for multiple animals.

“Mother Pavilion”

Studio Morrison

Completed: 2020

Location: Wicken Fen Nature Reserve, Cambridgeshire, Great Britain

Area: 15m2

Client: Wysing Arts Centre

Photo credits: Charles Emerson

»Mother Pavilion is inspired by Richard Mabey's book 'Nature Cure', in which the author explores the Eastern region's beautiful and unexplored landscapes. The form is an inter pretation of the remarkable hayricks once found dotting this countryside. The timber used in the framing was felled from the artist's forest, and the walls and roof are made from local straw.«

Extension and renovation of a thatched cottage Nicola Spinetto Architects

Completed: 2020

Location: Hermeray, France

Area: 42m2 (extension) + 38m2 (renovation)

Client: private

Photo credits: Sergio Grazia

»The house is part of a group of 3 constructions, which all have the typical local form of a longère (a long, narrow dwelling) with its thatched roof.

Thatch has long been used to cover rural roofs, with widespread use due to the low cost of the material and the thermal insulation it provided. The interior construction is also made with cross-glued prefabricated panels from natural materials which allow the inner casing to be visible.«

Recreational farmhouse Åstrup

Have, NORRØN Architects, Marco Berenthz, Poul Høilund

Completed: 2020

Location: Haderslev, Danska

Area: 600m2

Client: private

Photo credits: Torben Eskerod

»As a homage to the local tradition of the Schleswig region, the steep roof unfolds as a thatched structure and connective tissue that connects the body beneath. The roof is inspired by the traditional building of the Haubarg region which all had steep roofs to store large amounts of hay.«

Flemish Barn Bolberg Renovation

Arend Groenewegen Arhitects

Completed: 2009

Location: Bavel, The Netherlands

Area: 280m2

Client: private

Photo credits: author’s archive

»The structure has components of the original ar chitectural form and consists of the wooden con struction, low black facade and large thatched roof. The Flemish barn was built around 1800. Partly the renovation began at the request of the municipality of Breda, intending to enhance the quality and character of the countryside at a location where urban expansion is being planned. Traditional woodworking techniques were used to restore wooden parts of the characteristic shape of the roof and the wooden construction.«

Bird observatory TIJ

RO&AD Architects + RAU Architects

Completed: 2019

Location: Stellendam, The Netherlands

Area: 150m2

Client: Vogelbescherming & Natuurmonumenten

Photo credits: Katja Effting; Drone: Merijn Koelink

»The TIJ bird observatory was built when sluices from the North Sea to the river delta system of Maas and Rhine in the Netherlands were opened to improve water quality, biodiversity and fish migration. Tij is thatched with local reed and has a timber structure that has been assembled at the site. Through its re-usability, modularity, materials, and contribution to the natural environment, it is almost completely circular and sustainable. It is temporary, can be disassembled and will be taken apart in the future. At that time, it may be reused or recycled without detrimental effects to nature or man.«

Animame Algarve Yoga Pavillion

Jonathan Cory-Wright and workshop volunteers

Completed: 2022

Location: Alcantarilha, Portugal

Area: 50m2

Client: private

Photo credits: Cris Coa

»The substructure was built as part of the Learn Bi0n workshop, and the roof was made using a straw sewing process. The challenge of the project was to cover the domed structure, since straw, which is otherwise an ideal material for covering cane structures, is limited in terms of design ca pabilities. The slope of the roof should be around 45 degrees, but by no means less than 35 degrees. The latter dictated the method of covering and the opening of the roof in the middle of the building.«

Nile Safari Lodge

Localworks Architects

Completed: 2019

Location: Mubaku, Uganda

Area: 2,230m2

Client: NOVAM

Photo credits: Will Boase, Gio and Moh

»A series of roofs floating above the landscape offer visitors a connection with the surrounding space. The geometry of the roof responds to the surrounding conditions – a large number of trees and steep topography. Straw from the northern part of Uganda, as a typical material for vernacu lar structures in Uganda, connected the building to the local context. Local masters prepared sam ples so that it was easier to decide on the best technique and structure of production.«

Straw Ranch

Cinco Patas al Gato and Biocons Architects

Completed: 2020

Location: Ita, Paraguay

Area: 178m2

Client: private

Photo credits: Diego Saravia

»We started from the client's desire to recreate the home his grandmother had, hence the idea to use this roofing. The materials used are affordable, like concrete, bricks with colored earth mortar and white bricks for paving, raw iron that rusts with time and masonry furniture. The openings are standardized.«

Archive photography authors: 1. Fran Vesel, Slovene Ethnographic Museum archives 2. Franči Šarf, Slovene Ethnographic Museum archives

3. Marija Makarovič, Slovene Ethnographic Museum archives 4. Franči Šarf, source: Žetev in mlatev v Prekmurju. Etnografija Pomurja I, (p. 60)

5. Pošta Slovenije: Slamnati dožnjek, 1994

6. Fran Vesel, Slovene Ethnographic Museum archives

Title: Slamnata streha English title: Thatch roofing

Editor: Maša Ogrin Layout and design: Urška Alič Photography: Jana Jocif Illustration: Tamara Likon Translation: Katja Cvahte and L. P.

Project authors: Maša Ogrin Nina Vidić Ivančič Workshop host: Makrobios Panonija so.p. Public relations: Lena Penšek Workshop lecturer: Katarina Živković

Workshop participants: Ajda Žagar Christian Štor Domen Korelc Eva Bratina Jakob Podlesek Jakob Šubic Jan Maček Jure Ule Katarina Kušar Klavdija Rauter Lovro Levar Maja Pisnik Pia Gerbec Tamara Likon Tea Pristolič and others

Thatch roofing / Slamnata streha workshop was held between the 14th and 16th of October 2022 in Gornji Petrovci, Slovenia.

The publication was part of the project Thatch roofing / Slamnata streha in cooperation with Zavod za socialni razvoj Murska Sobota.

Project was co-financed by the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Slovenia.

Ljubljana, November 2022