Gretchen Albrecht

Gretchen Albrecht

between gesture and geometry

Luke Smythe To Jamie and AndrewGretchen Albrecht and I first realised we had a certain affinity when she came to stay with me in Florence in the spring of 1992. I had received an Italian government scholarship to research my master’s thesis. After four months working in isolation in libraries I was looking forward to her company. When she arrived Gretchen dropped her bag, and almost immediately asked if I would walk her around the city, ‘speaking’ my thesis as we went.

Rather than the grander paintings of Renaissance art, my research was based on works that were less well known but held important clues about women’s real lives, a history at the time half hidden in a city carrying the full weight of Renaissance art and culture on its shoulders. Over the next few days we visited frescoes and wall panels of the pregnant Madonna and Nativities tucked away in museums or newly discovered under later wall coverings in local museums and churches. At every step Gretchen questioned, concurred, challenged and absorbed what I was hoping to elucidate. By the end of her stay I felt I had drawn my research together for the first time, but I also had absorbed new ways of seeing.

Gretchen revealed to me her own approach to Renaissance art and how it had fed into her own practice within abstraction. I had viewed the columns and lunettes and arches as secondary to what was depicted within them, but her artist’s eye translated them into forms that could shape and contain her painting.

If Renaissance art marked the beginning of our friendship, over time the dynamism of the Baroque entered our shared vocabulary. Caravaggio’s light and shadow as mediums for meaning; Borromini’s lantern and oculus in the Roman churches of Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza and San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane — elements that work their way into her oval canvases, such as Nocturne (The Spiral Unwinds) (1991) and Nomadic Geometries (Dancing Shall it Name) (1993) — discussions woven back and forth, from inspiration to elucidation, to a broadening of understandings.

Later, speaking of her own first visit to Italy in 1979, she recalled: ‘a revelation about the power of painting hit

me when I looked at these historical works. The ability of paintings to emotionally affect and carry meaning is as relevant today as it was then . . . aspects of the everyday [are] found in many Renaissance paintings — [the] things we all recognise and can share can also be imbued with a sense of mystery and significance.’

Gretchen’s canvases are sites of containment where meaning is explored, revealing truths that are both specific and universal. Instead of depicting the Virgin’s response when the Angel Gabriel, his wings still in the act of folding, tells her she has been chosen above all women to bear the son of God, in Gretchen’s painting The Annunciation (1992) the message becomes gestural as the movement of narrative is translated into the fluidity of paint itself. Sweeping arcs of colour, the deepest blue shimmering against delicate pink, two quadrants fraught with a pause, an expectation, a desire, an acceptance, are captured within the tracing and retracing of the hand, the brush, the palette knife or squeegee in a broad arc over the canvas, so that we feel movement, absorbing the essence of narrative. Her paintings are kinaesthetic, like Leonardo da Vinci’s Measure of Man, the span of a human’s arms encapsulating our existence.

Words — as titles, inscriptions, counterpoints, epiphanies — are an intrinsic part of Gretchen’s paintings, leading us over the decades through the milestones of human existence. Her love of poetry is equalled by her acute observation of nature in all its fire and beauty: the last of the light at Piha as the sun slips beneath the horizon, the blaze of red in a summer pōhutukawa. The wild west coast’s black sand becomes a metaphor for grief — the death of a parent, a friend, someone’s darling child; the engulfing power of grief replaced with a silent mourning, a gradual acceptance: Seven Sorrows of Mary (Burial) (1995); Meditation (My Father’s Spirit) (1996); Darkening Lake (1997) — the rise and fall of gesture replaced with stillness, reflection, imponderable depth. These are universal themes of love, friendship, nurturing, loss and grief that can only be addressed from a lifetime of experience.

Mary Kisler, Curator Emerita, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

Poetry’s impulse to use metaphor, to discover resemblance, is not to make comparisons . . . or to diminish the particularity of any event; it is to discover those correspondences of which the sum total would be proof of the indivisible totality of existence. To this totality poetry appeals . . .

— John Berger‘I PAINT WITH MY BACK TO THE WORLD,’ the abstract artist Agnes Martin once declared.1 For Martin, who painted simple stripes and grids, abstraction was a way to escape reality into a perfect realm of geometric order. She saw this order as a source of reassurance in a world she found messy and unpredictable.

Gretchen Albrecht has a similar understanding of her own abstract work. ‘I think I paint to still the anguish I feel in my heart,’ she wrote in the early 1980s; ‘To order the chaos I sense is just outside the magic circle I draw around me with my painting.’2 She, too, employs abstraction in this process, but keeps her painting anchored in the real world. Although a great admirer of Martin’s work, she has no wish to escape from reality, which is why she invests her compositions with worldly associations. Her softly striated paintings of the 1970s evoke the layering of the landscapes that inspired them. Later series, like her hemispheres and ovals, and her more recent rectangular paintings, allude to many other themes and subjects. Abstract artists of a purist persuasion, like Martin and many of the genre’s greats, would find these references unwelcome, but for Albrecht they are a part of the chaos that she is trying to keep at bay in her art.

Rather than attempt to escape from the world’s disarray, she seeks to give it structure in her work, drawing on the power of abstraction to assist her in this process. Her paintings of the 1970s distil a basic order from the landscape that becomes apparent only when we abstract it. In her hemispheres and ovals, she refers to an array of phenomena that in concrete terms seem wholly unrelated. All, however, have a broad association

with semicircles or ellipses. She uses this abstract affinity to weave a network of correspondences between them. As in her works of the 1970s, but in a more complex fashion, these shaped paintings use geometric structure to proffer an experience of reality that is more orderly and reassuring than would normally be the case. Reality itself remains unchanged, of course, but we are coaxed by Albrecht’s paintings to see it through a more comforting lens. It is this distinctive capability of impure abstract art that she has worked with for close to fifty years.

Focusing primarily on painting, but also working in a range of other media, Albrecht has developed an abstract idiom in which shapes and their associative potential feature prominently. Colour and free-flowing gesture are also integral to her practice, as is the written word in the guise of her evocative titles. Allusive and descriptive in equal measure, her titles help us grasp the connotations with which she has invested her imagery. Placing these focal aspects of her work in the service of her search for reassurance, she fashions images whose poetry and power derive from the several kinds of experience they elicit. The first of these is physical. It consists of the felt intimations of expansion and contraction, implied movement and implacable stasis that her colours, shapes and brushwork awaken in us. With the promptings of her titles, these forms become suggestive of the real world and our immediate response to them is joined by the thoughts and feelings they call forth. Musing on how works of such economy can give rise to this multi-threaded experience is one great pleasure of encountering Albrecht’s art. Another is tracing her enrichment of this dynamic from one abstract series to the next. This book surveys the different stages of that process, along with the early years of her practice, in which, throughout the 1960s and the early 1970s, she slowly made her way toward abstraction.

During that initial phase of her career, Albrecht struggled to find her feet as an artist while juggling the demands of solo motherhood. It was only through sheer perseverance and occasional moments of good fortune that she was able to establish herself professionally and, by the end of the 1980s, secure her position as one of New Zealand’s leading painters. In the years since her rise to prominence, her work has received considerable attention, with the hemispheres and ovals proving to be especially popular. There are many other series, however, that have received less exposure, and in some cases have faded from public memory. Her collages of the late 1980s, for example, were last discussed by Linda Gill in the early 1990s, when she published the first survey of Albrecht’s work. Gill’s concise yet informative study remains an invaluable resource, but now covers only half of Albrecht’s output. In the time since it appeared, much of the early work it addresses, from the 1960s and 1970s, has also been forgotten. With several decades of new work to take account of, and new archival sources available that shed light on many of the early series, there is much that

can be added to Gill’s account. There is also scope to bring together insights from the many other writers on Albrecht’s work and assess these in the context of a new synthetic overview of her practice.

As this book tracks the vicissitudes of Albrecht’s pursuit of reassurance, it undertakes this second task as well. From the ensuing discussion of both the insights and the oversights of past commentators, a clearer picture of her achievements is established. Her paintings of the 1970s, for instance, are shown to be distinctive precisely by virtue of their impurity. At a time when abstraction in New Zealand was viewed in purist terms by nearly every critic and artist, the landscape references of her stained canvases were unusual. More abstract than the expressionist landscapes of older figures like Colin McCahon and Toss Woollaston, but less abstract than the geometric paintings of her male contemporaries, this series was an outlier of the period. This situation soon changed, however, and by the mid-1980s an impure approach to abstraction had become the norm. Albrecht’s status as a pioneer in this regard needs to be acknowledged, something that has yet to occur.

As several earlier authors have acknowledged, and as this book reaffirms, Albrecht was also a forerunner of the women’s art movement, which rose to prominence in New Zealand in the early 1980s. At that time, she was attacked in some quarters for failing to tackle social issues in her work, and for making paintings that were allegedly unfeminine. Both charges were tendentious, however, because they rested on narrow views of what it meant to be a feminist and a female artist. A more open-minded assessment of Albrecht's practice makes her credentials as a feminist abundantly clear. In addition, it reveals that she anticipated key aspects of feminist art practice in her work of the 1960s and 1970s. Clarifying these and other matters affirms the importance of her position within the histories of abstraction and women’s art in this country.

History only matters, of course, if it enriches our sense of art’s significance in the present moment. It is here that this book hopes to make its most important contribution. Like any art worth looking at, Albrecht’s work requires no assistance to convince us of its merits. It is the task of an art writer, however, to offer his or her assistance — whether needed or not — by furnishing responses to the work that enhance it for other viewers. Just as Albrecht’s paintings refine our experience of reality, so the text that follows aims to do the same for the viewer’s experience of the paintings.

1963 – 1970 models of expression

Godley Road, Titirangi, 1964 Photograph: Des DubbeltGRETCHEN ALBRECHT’S INTEREST in art developed at Mount Roskill Grammar School in Auckland in the late 1950s. Prior to this point, she can recall being fascinated by her mother Joyce’s bag of sewing scraps and she also took an interest in the construction projects of her father Reuben, a builder. Not until her teenage years, however, did she feel an inclination to paint and draw, an urge that surfaced in the classroom of her art teacher Colin de Luca. Initially, she had planned to study French, but after visiting de Luca’s class she felt drawn to its panoply of sights and smells and asked her parents to let her switch to art.

By the standards of the period, de Luca was unusually progressive. At a time when the art curriculum stressed techniques like copying Michelangelo, de Luca ringed his room with reproductions of works by leading modernists, from late-nineteenth-century masters like Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Cézanne to recently deceased figures like Chaim Soutine and Henri Matisse. He asked his students to study these images carefully, to commit their dates, titles and makers to memory, and to write personal responses to what they saw. He also made a point of screening documentaries showing artists at work. Among these were Paul Haesaerts’s A Visit to Picasso (1949), Hans Namuth’s Pollock (1951) and a third film (whose title Albrecht no longer recalls) showing Matisse developing his painting Pink Nude (1935). Albrecht was receptive to de Luca’s teaching from the outset, and by the end of her last year at high school she was determined to become a painter. With de Luca’s help, she prepared a Fine Arts preliminary portfolio for acceptance into Elam (later to become the University of Auckland School of Fine Arts), and began a Diploma of Fine Arts in February 1960.

During her four years at Elam, Albrecht received instruction in painting, design, drawing and art history. Here, too, the curriculum remained conservative, with still-life and figure drawing the major focus of instruction. Although she chafed at this traditionalism, Albrecht took heart from the fact that half the painting staff (Louise Henderson, Ida Eise and A. Lois White) were women. She also enjoyed her drawing classes with Jim Allen, who encouraged her to work with greater freedom and directness.

Most memorable of all were her art history classes with Arthur Lawrence and Kurt von Meier, which instilled in her a number of abiding interests. Lawrence imparted to her his love of the Romanesque and Renaissance, which later became touchstones for her work, and von Meier exposed her to the work of female modernists such as Paula Modersohn-Becker, Gabriele Münter, Käthe Kollwitz and Sonia Delaunay. He also introduced her to the work of Frances Hodgkins, whose Self Portrait: Still Life [p.42] he took her to see at Auckland City Art Gallery. Not all of these women would influence Albrecht’s painting, but each stood as a model of the serious and successful female artist, able to persevere and prosper in a field that remained male-dominated.

Paula Modersohn-Becker

Paula Modersohn-Becker

AS THE FOREGOING list of painters suggests, von Meier’s teaching emphasised Expressionism, a style Albrecht adopted for her own work at Elam. Key expressionist models for her first paintings of note, including Susannah and the Elders [p.15], which she produced in 1963, her honours year, were Modersohn-Becker [p.14] and Emil Nolde. 1 The self-portraits of Modersohn-Becker encouraged her to place her own experience at the heart of her painting and to use a naked female figure as her pictorial stand-in. From Nolde she took a raw approach to paintwork, a preference for strident, unmixed colours, and a predilection for thickly applied pigment. In an added parallel, she echoed his depictions of encounters between imaginary creatures, investing her own compositions with a similar sense of childlike simplicity. She parted company with Nolde, however, at the level of her work’s motivation. Nolde’s scenes are playful fantasias, born from his love of myth and folklore, but Albrecht’s more earnest paintings related to her challenging life circumstances. 2 Although she was only 20 at the time they were produced, her recent life had been enormously difficult.

Shortly after starting at Elam, she had begun a relationship and become pregnant. Under pressure from their parents, the couple had married and moved into a flat in Devonport. A few months later, Albrecht contracted pregnancy-induced toxaemia, a form of blood poisoning, and was hospitalised. After fighting off the illness, she gave birth to a son she named Andrew, at which point she and her husband moved in with her parents in Mount Roskill. Albrecht was determined to maintain her studies and was supported in this decision by her mother, who volunteered to look after Andrew. Already, the marriage was unravelling and it was only with her parents’ assistance that she was able to complete her degree: not surprisingly, Albrecht’s first taste of adulthood was a far cry from the peace and security of her fondly remembered childhood. 3

This was an abrupt coming of age, so it is little wonder that Albrecht’s paintings from this period seemed to face in two directions at once. Stylistically, they reached back to her fast-receding youth; their themes, however, were entirely adult. Typical in this regard are Susannah and the Elders (1963) [p.15] and The Suitor (1964) [p.17]. In both works a naked woman is encroached on by a male admirer with animal attributes: plumage (or perhaps antlers) in the case of the Elder, and a pair of goat-like horns in the case of the Suitor. By virtue of this bestialisation, these figures can be taken as embodiments of male sexual instinct, albeit of opposing persuasions. The Elder is a predatory figure, the Suitor his romantic inverse: his features are more refined, he discloses his presence openly, and he bears with him a token of his affections in the form of a radiant bouquet, a device Albrecht adapted from Modersohn-Becker.

In contrast to Susannah, who looks troubled by the Elder’s proximity, the woman being courted by the Suitor greets him happily and welcomes his advances. As Linda Gill has noted, these images concern relations between the sexes, which they address on both public and private levels.4 Publicly, they use allusions to myth and archetype to capture the perennial ambivalence of sexual interactions. Privately,

Adramalech, a Rebel Angel D13

Untitled D9

Untitled D4

Fool, Beast & Woman (D15)

works 1964 pencil on paper 56 x 38 cm

Wellington

Untitled D3

Angel Playing Bach

Erika and Robin Congreve, Auckland Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, All

Untitled D3

Angel Playing Bach

Erika and Robin Congreve, Auckland Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, All

Regatta 1 1965

Regatta 1 1965

they relate to Albrecht’s personal experience, and in light of the breakdown of her marriage, they can be taken as expressions of her own mixed feelings about men. Though disappointed by her husband, her romantic ideals remained intact and she continued to hold out hope for a better partnership.

In rendering the woman in The Suitor, Albrecht took inspiration from Pablo Picasso. She had used the funds from the Fowlds Memorial Prize, awarded to the most distinguished honours student at Elam, to buy the newly published Les Déjeuners (1962), a lavish publication that reproduced Picasso’s drawings after Edouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe. Her painted nudes from 1964 bear the imprint of Picasso’s supple contouring, as do the figures in a suite of pencil drawings she created that same year.

In part her decision to make drawings was a matter of expediency. Since leaving art school she no longer had a studio and could not make large paintings. Andrew was increasingly active, so she had less time for art and was wary of leaving turpentine and paint within his reach. Rapid-fire drawing allowed her to continue working, while also fostering a shift of emphasis in her technique. Instead of working up an image in stages and investing it with preconceived significance, she improvised her drawings in a single session, savouring the challenge of conjuring invented forms quickly with a series of spontaneous hand movements. The ensuing compositions feature mythic scenes like those found in her paintings. In one untitled image [p.18], a mother protects her child from a looming male figure. In another Adramalech, a rebel angel who appears in Milton’s Paradise Lost, swoops in to seize a startled woman [p.18]. Here too, then, predatory men continued to loom large in her imagination.

But not all men fit this model, and it was thanks to male sponsorship that these works were shown in public, at Albrecht’s first solo exhibition. While visiting Auckland City Art Gallery, she had a chance encounter with Hamish Keith, who asked to see the drawings she had with her. Impressed by what he saw, he encouraged her to show them to Colin McCahon, at that time the gallery’s deputy director and keeper of its collection. McCahon also liked what he saw and arranged an exhibition for Albrecht at Ikon Gallery. This was a highly unusual act of sponsorship for an artist only one year out of art school, let alone a woman artist. Speaking at the exhibition’s opening, McCahon placed Albrecht in a lineage of talented female artists in New Zealand that reached back to Frances Hodgkins. A newspaper review quoted McCahon’s opening speech and the well-received exhibition earned Albrecht a reputation as a promising young artist.5

This warm reception notwithstanding, in the wake of the exhibition Albrecht shifted course dramatically. Wishing to open her work more fully to the real world, she left behind imaginary imagery and began to work with media photographs. For the most part, these were sourced from British periodicals, either newspapers like The Observer and The Sunday Times or magazines like Nova, a progressive women’s magazine from London that was a favourite of Albrecht’s at this time.6 In keeping with their international provenance, most of the images she worked with related to current global events, and the US intervention in Vietnam formed a notable focus of several paintings from this period. Our Man of the Year (1966) [p.23],

Vietnam Painting 1965

Vietnam Painting 1965

for example, featured the head of US president Lyndon Johnson in its upper right-hand corner and a white dove of peace exiting the image at its lower left. Like many young New Zealanders in the 1960s, Albrecht was active in the peace movement and had joined CND, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, some years earlier. The title of this work is an ironic allusion to Time magazine’s choice of Johnson, escalator of the US war effort, as its ‘Man of the Year’ in 1965.

Other works from 1965 and 1966 addressed contemporary New Zealand subject matter and were culturally affirmative rather than critical. Regatta 1 (1965) [p.20], for instance, is a lively celebration of beach culture that constellates found images of bathers with bright blocks of colour, animated patterns and hand-painted figurative motifs. The source photographs for this painting and others were taken by a friend, Des Dubbelt, at Mount Maunganui.7

In both these groups of paintings Albrecht’s treatment of her source images was redolent of Pop Art, which by the mid-1960s was a well-established international art movement. She does not recall a conscious engagement with Pop, but by this stage its visual sensibilities had filtered through into the wider culture, making it all but inescapable. It is therefore unsurprising that her work of the mid-1960s recalls the painting of prominent Pop artists like R. B. Kitaj and Robert Rauschenberg, who took a painterly approach to their photographic source material.8 When glueing or silkscreening photographs onto their canvases, these artists fringed or juxtaposed them with passages of freeform brushwork. When copying them by hand, they altered them considerably, dissolving them in clouds of abstract paintwork, surrounding them with abstract patterns, purging them of detail and so forth.

It is a measure of Albrecht’s ingrained expressionistic sensibilities that she also favoured such techniques. Working in this painterly manner allowed her to manipulate the impact of the photographs she worked with, as is evident in Regatta 1. To heighten the impression of the sun’s intensity in the photographs, she overpainted their backgrounds in stark white, a colour she used elsewhere in the image to convey an effect of seering brightness. This occlusion had the added consequence of highlighting the figures in the photographs, strengthening their impact within the painting as a whole.

In a later group of paintings, from 1967, Albrecht’s manipulation of photographs grew more pronounced and her work’s Pop sensibilities began to fade. Though she still looked to the media for inspiration, she now reduced her photographic sources to a near-flat arrangement of coloured shapes. So schematic and mellifluous are these images that at times they are entirely illegible, as is the case in some parts of Wooden Horse (1967) [p.27]. In this painting and others like it she continued to engage with mass culture, but she now distorted and re-imaged her sources in a thoroughly expressionistic fashion.

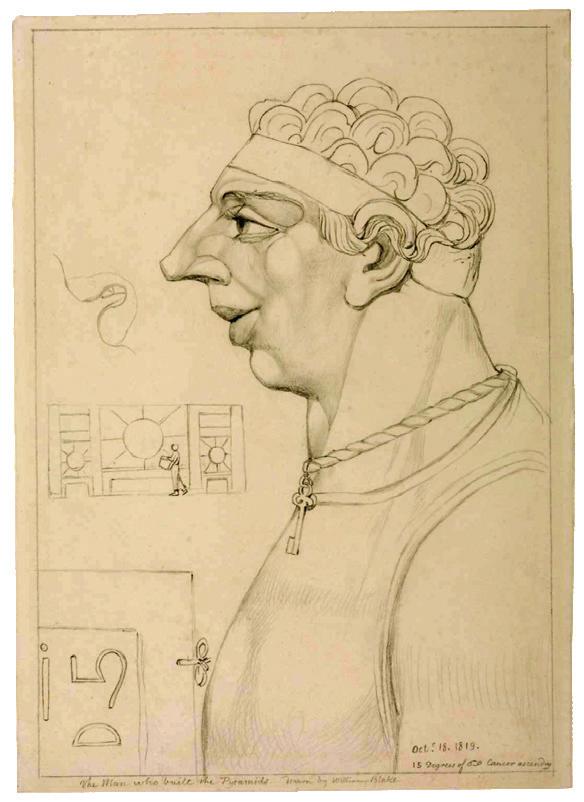

Elsewhere in her work from 1967, she began to use other source material. The head in profile in Pyramid Builder (1967) [p.25] derives from The Man who Built the Pyramids (c.1825), a drawing by John Linnell after a lost William Blake. The still-life below the head is indebted to Pittura Metafisica, an Italian painting

Attributed to John Linnell

The Man who Built the Pyramids (after William Blake) c.1825 graphite on paper 29.8 x 21.4 cm Tate Britain, London

Attributed to John Linnell

The Man who Built the Pyramids (after William Blake) c.1825 graphite on paper 29.8 x 21.4 cm Tate Britain, London

movement from the 1910s.9 A key exponent of this trend was Giorgio Morandi, who included a mannequin’s head in his early still-lifes. Albrecht also used this device in Pyramid Builder. By connecting her objects to the head of a living being and tightly enclosing both within a circle, she suggested that her still-life was a mindscape of some kind: the riddling contents of her painted figure’s psyche.

That the paintings in this vein were perhaps too enigmatic for their own good became evident in July 1967, when Albrecht showed 14 of them at Barry Lett Galleries in Auckland. Unable to make sense of what they saw, the critics who reviewed the exhibition deemed her new work unsuccessful. The Star’s I. V. Porsolt, for example, was impressed by her technique, but when it came to content he found her paintings wanting. In striving to invest her cryptic imagery with weighty symbolic significance, he felt that her ‘age [had let] her down’.10 The Herald’s T. J. McNamara saw potential in her ‘surrealist’ approach, but on the whole deemed it lacking in coherence. ‘This exhibition,’ he concluded, ‘is the work of a still immature painter who is working her way toward accumulating a vocabulary of expressive forms.’11

Albrecht had similar reservations. Although the photo-based works like Wooden Horse appealed to her formally, she felt that her distortions of their imagery were seldom related clearly to their subjects; her treatment of her photographic sources thus seemed arbitrary. She found her metaphysical works, like Pyramid Builder, more suggestive, but faulted them on technical grounds. In her view, they were too ‘stiff’ and ‘rigid’ to be convincing.12

Given her living circumstances, these shortcomings were hardly surprising. She had separated from her husband in 1966, and with no state social welfare benefits yet available for solo parents, she was struggling more than ever to look after Andrew. With no prospect of earning a living from her art (an impossibility for all but a handful of well-established figures at that time), she was obliged to find another source of income. She thus enrolled at Auckland Teachers Training College, and after earning her Teacher’s Certificate in 1967, she worked at first in a ribbon factory, then in a temporary role at Mount Roskill Grammar before landing a permanent position at Kelston Girls’ High School. Between her childcare and work commitments, finding time to paint was near impossible. As she explained to Priscilla Pitts some years later, the works in her second exhibition were the best she could produce under the circumstances: ‘I don’t think they were particularly good . . . but they were a sign of life, they were me still trying to keep on keeping on.’13

Thankfully, this grind became less taxing after Albrecht met James Ross, an art student who flatted with her brother. Their relationship began late in 1966, and as they grew closer in the years that followed, the tenor of her work began to shift. Setting aside Pittura Metafisica, she started making freer, brighter images that were directly observed from life. In these works vivid colour and supple line work returned to the forefront of her practice and a new source of inspiration became apparent: Henri Matisse. With colour and vitality returning to her life, Matisse became a fitting touchstone for her art. Accordingly, in the late 1960s, she produced works in several media that echoed both Matisse’s paintings and his cutouts.

Wooden Horse 1967

acrylic on canvas 98 x 83.5 cm

Wooden Horse 1967

acrylic on canvas 98 x 83.5 cm