7 minute read

THE LORDS OF THE SAVANNAH’S FAMED BEADWORK

work

Intricately beaded art, like a kaleidoscopic spiderweb, has become an emblem not only of the Maasai tribe’s East African homelands, but even of the spirit of adventure that encapsulates Africa itself. Words and pictures by Mark Eveleigh

Advertisement

The statuesque warrior with the shimmering earrings, bangles and shining assegai (spear), and the dark maiden with the undulating necklace framing her face have become East African icons.

Yet these colourful images are a relatively recent import. Traditionally, the Maasai created their jewellery using natural materials such as grass, shells, seeds, clay, wood and bone. Cowrie shells from the Swahili Coast were (and still are) particularly sought-after, and later, explorers and slavers – both Europeans and Arabs – brought trade-goods in the form of copper, brass wire and eye-catching glass beads that captivated the Maasai, all too often literally.

More recently, as trade spread into the interior, backcountry dukas (general stores) opened – often run by entrepreneurial Indian immigrants – and production of Maasai beadwork became even more prolific as a result of a profusion of more readily available and inexpensive plastic beads. The dukas also supplied cheaper versions of the checked red and black blankets that replaced the traditional Maasai shuka robes. To this day, Maasai will recognise fellow clansmen by their blankets much as Scotsmen will celebrate the sight of familiar tartan (although in the case of the Maasai, it is less a tribal emblem and more simply the fact that a particular blanket has become popular at the local duka).

At 72 years old, Kipinketene Sankaire is old enough to remember a time in her remote manyatta (village) near NairagieEnkare when most jewellery was made from less colourful natural materials.

“Those were happier days,” she says. “The materials we used were strong and bones were plentiful. The land gave us what we needed; we collected scented grass to make perfumes and we made belts out of hides. It’s unlike now when everything has to be bought and many Maasai just produce their beadwork as a stepping stone for other people’s businesses.”

As in Western culture, the use of more intricate and abundant jewellery will show a person’s status, but Maasai can decipher a wealth of information about an individual’s class, clan or marital status with just the merest glance at their jewellery. While a married woman will wear a long necklace of blue beads known as nborro, unmarried women will sport a wide and beautiful beaded necklace that, during dances, undulates hypnotically with a movement said to be reminiscent of the dewlaps of the tribe’s precious cattle.

When a girl is married, she might wear a necklace that reaches even to her knees. Often there will be long strands hanging from it to represent the dowry of cows that will be paid to complete the union. These marriage collars may become highly prized heirlooms – the possession of which is matched only by the possession of the all-important cattle – and visitors should consider very carefully before tempting local people into parting with them.

Throughout Kenya and Tanzania, bead adornments, often now made from cheaper plastic or glass, have become an important source of income for many Maasai, with many visitors wanting to take home a tangible souvenir from their safari that will remind them of the legendary aristocrats of the savannah. The tribe’s northern cousins, the Samburu, have a historical

Above:

Designer Anna Trzebinski and some of her Maasaiinspired works

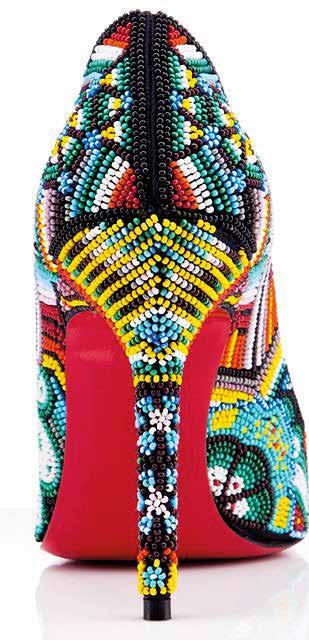

Right:

Christian Louboutin Maasai-inspired heels tradition of beadwork all of their own that is all too often overshadowed by visitors who are unaware of the often subtle cultural distinctions between the region’s many tribes.

Outsiders often detail the significance of colour choice (usually relating to the tribe’s precious cattle; white for milk, green to signify lush grazing, etc) but the Maasai themselves invariably deny this and claim that they simply choose colours that appear attractive together.

African Heritage was established in 1978 as the first Pan-African gallery in Africa and once housed the finest collection of African beadwork in the world. Boasting 500 craftsmen and 51 outlets, African Heritage was once described by the World Bank as ‘the largest, most organised craft retail and wholesale operation in Africa’. Lately, The African Heritage Design Company (renamed after it acquired new ownership in 2003) has been focusing on exports and has opened a new outlet at Nairobi’s Villa Rosa Kempinski that offers contemporary home décor pieces inspired by the Maasai and other communities.

“Our goal is to make a difference to local communities,” says owner Makena Mwiraria. “We don’t want to just work with a community and then leave them in the same situation we found them. An export operation like ours – involving Maasai beadwork – could provide jobs for hundreds of women, and we can also help them by supplying household items that they need – solar lights for example.”

The influence of Maasai beadwork has reached far beyond the dusty game-trails of East Africa and onto the polished catwalks of Europe, where dresses by Emilio Pucci and elegantly beaded stilettos by Christian Louboutin have wowed the fashion world. British designers Kokon To Zai produced an entire line of beaded clothes that they call ‘Maasai Punk’. Anna Trzebinski (www.annatrzebinski.com), perhaps Nairobi’s most famous designer, has developed Maasai beadwork in subtle ways to produce gems like her Tibetan pashmina and silk shawl which is trimmed with ostrich feathers and Maasai beading, and her ‘Maa Gladiator’ goat-suede and bead sandals.

“The Maasai are held in high esteem for their continued respect for their culture, and their beadwork has become known as one of the most celebrated and widely recognised forms of tribal jewellery. Even in an era when many Maasai children are leaving to look for work in the cities, some excel in art. Maasai beadwork is becoming more popular and these young Maasai will be the cultural ambassadors of their people’s artistic tradition in the future,” says Mwiraria.

FACT-FILE

Getting there and around:

It is possible to take domestic flights to safari hotspots such as Maasai Mara and Amboseli in the heart of the

Maasai homelands. Most visitors arrange domestic transport as part of a safari package but for those with an intrepid streak, it is possible to hire fully equipped self-drive safari vehicles from reputable companies like Erikson Rover Safaris (www.roversafari.com).

Where to stay

For many people, a visit to a Maasai community or a trek with warrior trackers is an unexpected highpoint of their East African safari. Porini Safari Camps (www.porini.com) have wonderful safari properties in Maasai conservancy areas in Maasai Mara and Amboseli regions. Apart from offering some of the best guided safari game-drives and walks in Africa, they also work closely with local Maasai communities and provide insightful tours of local manyattas and warrior camps. Gamewatchers (www.porini.com) offers a 6-night Porini Migration special offer safari with a night on arrival at Nairobi Tented Camp, followed by accommodation at their Porini Camps in the Maasai Mara on an all-inclusive basis (including meals, soft drinks, wine, guided bush-walks with the Maasai, day and night drives with qualified Maasai guides, conservancy, and park fees), with return flights from Nairobi.

Where to experience tribal cultures

While Kenya’s Maasai Mara is often seen as the Maasai heartlands, Tanzania’s celebrated Serengeti National Park and Ngorongoro Crater are also unbeatable safari locations in Maasai territory. Serengeti and Maasai Mara are world famous for the great wildebeest migration – known as the greatest wildlife spectacle on earth – but if you want to avoid crowds and have the freedom to explore on foot, choose to stay at a tribal conservancy on the fringe of the Mara (the park is unfenced anyway so wildlife is just as abundant on the boundaries). For a completely different safari experience, head to the Samburu National Reserve where Saruni Samburu

(www.saruni.com) offers an unbeatable insight into the Samburu, the Maasai’s less famous but equally aristocratic northern cousins.