6 minute read

Rivers of Red Rock

Adventures in Mauna Loa’s lava zone

By Dan Collins

Advertisement

canoes, flows for a long distance before it cools and hardens, forming a broad, gently sloping dome, shaped like a warrior’s shield laid flat. The lava initially pours out like thick cake batter, creating smooth, pillowy structures as it cools, which Hawaiians call “Paho‘eho‘e”.

As the lava flowing downslope begins to cool, it starts to crust over. But the swelling lava underneath the thin crust causes it to crack and crumble as quickly as it cools, creating a nearly impenetrable land-

The dry Western slopes of both mountains show little change from when they were formed, aside from the scrub brush that has taken hold amidst the black rocks that stretch for miles. But their windward slopes, pummeled relentlessly over time by tradewinds and the wet weather they bring, sport lush canyons and deep gulches carved by hundreds of thousands of years of wind and rain.

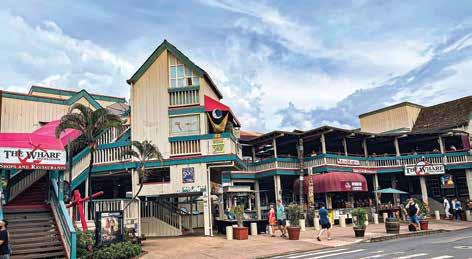

Concerned by the risk posed by volcano watchers parked on the narrow shoulder alongside a busy highway, oweo, and then migrated to the Northwest rift zone, one of two sections of fractured basalt downslope where there are deep fissures from which lava has historically emerged. It typically produces slow-moving flows that advance at a walking pace, presenting little risk to onlookers. scape of jagged boulders with edges as sharp as glass. The Hawaiians dubbed this type of lava “‘A‘a”. authorities smartly opened up an older, parallel route that lies closer to the eruption for viewers to use. It was already filling up with parked cars as we arrived at dusk. But persistent clouds blowing in from the East obscured our view of the lava flow. All we could see was an orange-red glow illuminating the clouds overhead. So we parked and waited, hoping for a break in the weather.

Let’s back up a little bit and discuss how these intriguing structures form. Cracks in the Earth’s crust, or lithosphere, separate it into tectonic plates, which float on top of a subterraneous sea of molten rock, or magma, slowly pushing against each other, battering their edges and forming mountain ranges where they meet.

The area impacted by the November eruption lies roughly in the center of the island, in the saddle that is formed by the convergence of earlier lava flows from Mauna Loa and its big sister Mauna Kea, to the north. The vast lava fields between the two are bisected by the Daniel K. Inouye Highway, known locally as Saddle Road, which is the main route between the population centers on the East and West sides.

As is common, the November 27 eruption of Mauna Loa began in a caldera at the summit called Moku‘awe-

The Pacific Plate on which the Hawaiian Islands are situated is drifting slowly to the Northwest at about the same rate that your fingernails grow. Its snail-paced migration is propelled by magma pushing itself to the surface along the Southeast edge of the plate where it forms new crust on the seafloor in an arc extending from Southern Mexico to a spot about a thousand miles south of New Zealand. As it slowly creeps towards Asia, reaching speeds of up to four inches per year, the leading edge of the Pacific Plate is forced downward in a process called subduction, where it melts back into the Earth’s molten mantle.

(Continued on Page 12)

Along that edge where the Pacific Plate meets the Eurasian, Phillipine, and Australian Plates we can find many of the “stratovolcanoes” that form the Ring of Fire surrounding the Pacific. Stratovolcanoes are smaller, don’t erupt as regularly, and tend to have more explosive eruptions than shield volcanoes, like those found in Hawai‘i.

Hawai‘i’s shield volcanoes are different because they are not formed along subduction zones, instead being the offspring of one massive “hot spot” underneath the vast Pacific Plate which has been oozing lava for tens of millions of years, forming large, broad, rounded mounds of basalt which dwarf the smaller, steeply sloping stratovolcanoes.

Geologists believe that this one spot where intense heat and pressure force molten rock through the seafloor formed all of the islands in the 3,500-mile-long Emperor Seamount-Hawaiian Island chain over the last 70 million years. As the islands drift away from the hot spot, they grow older and more eroded, eventually becoming atolls, and then disappearing into the sea.

In addition to feeding Mauna Loa and nearby Kīlauea, this same lava source is also giving birth to the Lō‘ihi Seamount, a subaquatic volcano sprouting out of the south side of the Big Island, which, if it continues to grow at its current rate, will emerge from the ocean and become the newest Hawaiian Island in 60,000 years.

The Big Island was formed by the convergence of five volcanoes, all emanating from the same hot spot. At 13,796 feet (4,200 meters), Mauna Kea is the tallest. Measured from its base, it’s technically the tallest mountain on Earth. Subma- rine flanks extend another 16,400 ft. (5,000 meters) to the seafloor, bringing Mauna Kea’s total height to 30,085 feet (9,170 meters)—more than 1,000 feet taller than Mount Everest.

About 25 miles to the south, Mauna Loa stands about 125 feet shorter than Mauna Kea, but covers a vast 2,035 square miles, or about half the surface area of the island. Thirty-two eruptions of Mauna Loa have occurred since they were first documented in 1843.

Kīlauea appears as a bulge on the Southeastern flank of Mauna Loa and was believed to be a satellite of the larger volcano, however chemical analysis of lava samples from both indicate that they are fed by separate lava chambers. Historically, high activity at one has usually meant low activity at the other.

For instance, Kīlauea was dormant from 1934-52 while Mauna Loa was active. Then Mauna Loa went quiet from 1952-74, while Kīlauea remained active. But then, the 1984 eruption of Mauna Loa began during an active eruption of Kīlauea, with no discernible effect on one another.

Kīlauea was active at its summit almost non-stop from 1983 until 2018, making it the longest-lived rift-zone eruption of the last two centuries anywhere on Earth, and culminating with the collapse of the summit caldera at Pu‘u‘ō‘ō on April 30 of that year. But the mountain came back to life three days later when a fissure opened downslope, beginning a four-monthlong eruption that wiped out a large section of the Leilani Estates subdivision near Pahoa, destroying 700 homes and displacing 2,000 residents.

While Kīlauea has become active relatively recently, it hasn’t been dramatic enough to convince me to make the trip. So, until this visit, I had never seen lava in person.

Safely parked off the road, we piled out of the car, staring in awe at the light show across the valley. Predictably, the young boys were quickly bored with the spectacle and retreated to the car and their iPads, emerging every few minutes to ask if we could go yet. Meanwhile, the rest of us braved the cold, excitedly snapping photos and filming the distant rivers of lava.

“I would have loved to have gotten closer to it, but being where we were didn’t take away from how amazing it was,” said Tronolone. “You could see the cinder cone up close with the long lens and it would shoot lava a ways off the top and you could see it landing and breaking apart.”

“I couldn’t believe how big a flow it actually was,” said Berg. “I’d seen lava before, but nothing like that. Not on that massive scale.”

The volcanoes on the island of Hawai‘i have probably been erupting on and off for the past 700,000 years, emerging from the sea some 400,000 years ago. The slow northwesterly drift of the Pacific Plate will take them away from the hot spot in the underlying mantle in another 500,000 to 1 million years. But this particular eruption lasted for just over two weeks—typical for Mauna Loa. During that time, lava traveled 16 miles from the Northwest rift zone to within less than two miles of Saddle Road. Then both it and Kīlauea went quiet, a day apart.

Returning to Maui, I’ve grown a new respect for our own dormant shield volcano, Haleakalā. It’s easy to imagine lava flowing from her summit and the many pu‘u that scar her slopes. Haleakalā last erupted between 423 and 543 years ago—barely a wink in geologic time. However, as long as the pressure from the magma hot spot continues to be released on the Big Island, and its offshore satellite Lōihi, the likelihood of Haleakalā coming back to life again is pretty slim. Or so they say.