13 minute read

Cancer

STRONG LONG

YUNLONG ONG’S QUEST TO OUTCLIMB CANCER

Yunlong Ong on the summit of Mt. Adams. Photo by Ian McCluskey.

by Ian McCluskey

On a sweltering July day, our climbing team returned to the trailhead after a successful summit of Mt. Jefferson. Packs laden with ropes, pickets, ice axes, second tools, tents, sleeping bags, stoves, leftover fuel, and ripe blue bags were dropped with a grunt. Leg muscles ached, heel blisters stung, and the grit of traildust and forest-fire ash stuck to sweaty skin. It was that moment when you want to peel off trail-grimy clothes and pour water all over your head, then look back at the now distant snow-capped peak and stupidly grin with a soul-deep sense of self-satisfaction.

For our climb leader, Yunlong Ong, it was his first successful Jefferson summit, having tried once before. Even more meaningful, it was the very first climb that he led as an official Mazama climb leader. Yet achieving these two hard-earned life goals was not the most significant thing on our climb leader’s mind.

I hobbled over to congratulate Yunlong—or “Long” as he’s known by friends and fellow Mazamas. As he peeled off his hiking shirt, I noticed the unnatural protrusion on his bare chest, just under his skin. Through this port had been pumped the potent chemicals to battle his gastric cancer.

This was his first climb after intense rounds of chemotherapy and resection surgery. His salt-and-pepper hair had started to grow back, but just three weeks earlier he had suffered two severe episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding, requiring transfusions, and leaving him weakened. Most people wouldn’t have decided to embark on something as strenuous as climbing a mountain.

But Long doesn’t believe in limitations.

Starting with the mountain considered Oregon’s most technical peak, Long began a personal quest to outclimb his cancer.

A Season of Blitz Climbs

After his successful summit of Jefferson in the summer of 2019, Long set out on nothing short of a mountaineering blitz. He attempted seven more climbs, reaching six Cascade summits. A schedule shift turned Middle Sister into a burly car-to-car push.

Just a few days later, I was with him as we zigged-zagged our way up the Emmons glacier on Mt. Rainier.

It was now late season. The snow had gone through so many thaw-freeze cycles that crampons and ice axes left dings on the hard surface but made no purchase. These conditions, and a sleepless night of howling winds, made the choice to turn back obvious. It would be the first, and only, unsuccessful summit attempt in Long’s push before the end of the Cascade climb season of 2019.

At the customary post-climb meal of burgers and milkshakes, he gave a little speech to the team. Then he got choked up.

Most know Long for his big smile. “Hey buddy,” he’ll say as his standard greeting, and if he likes something, it’s “cool beans.” In small social groups that he considers “like-minded,” he reveals his unabashedly playful nature. With his close friends, his form of endearment is to tease them.

But other times, he is often quiet. On climbs, he has an intense focus, his face covered by helmet, sunglasses, and balaclava. He keeps emotions guarded, even bottled up. So when tears come out, it often takes people by surprise. Sometimes it even takes Long by surprise.

“I’m sorry,” he said to the team after Rainier, though the team understood why we turned back. But it wasn’t the team that Long felt that he’d disappointed.

He wiped his eyes and collected himself. “I’m sorry,” he said again. “I was thinking of my dad.”

From the South China Sea

Long was born in Brunei, a tiny nation on the island of Borneo looking out across the South China Sea. Islam is the dominant religion and Malay the common language. But Long’s parents were Chinese. At home they spoke Mandarin and practiced Buddhism.

His dad worked as an air conditioning and refrigerator mechanic. But he had “foresight,” Long says. He enrolled Long in an English school, where Long learned to speak his third language.

His dad was a man of few words. He worked hard to be a provider, and told his two sons that “education was the way.”

In 1983, the family moved to Singapore. It is smaller in land-size than Brunei, but with more than 5 million people it is one of the most densely populated countries in the world. For his father, the move was an increase in the cost of living to support the family, but it also offered his children a path forward in their education. Singapore has one of the highest youth literacy rates in the world.

In 1996, Long earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Singapore—the first in the family to graduate college.

He felt the culture of Singapore was rigid, demanding conformity. The cultural expectation was for him to marry and immediately start a family. Long worked in youth development programs that he describes as similar to Outward Bound. But he didn’t get along with some of his colleagues, he says, due to his “rebellious nature.”

As Long travelled to various countries of Southeast Asia for his job, he saw life outside the relatively wealthy counties of Brunei and Singapore. The level of medical conditions made a big impression on him, and he felt he wanted to make life better for people. He realized that he could accomplish this through medicine. It was a lifechanging epiphany. When Long told his father that he wanted to move to America to study medicine, his dad said simply, “Go do what makes you happy.”

Becoming a Nurse and a Mazama

Long moved first to Denver, Colorado to earn a Bachelor of Science in Nursing, then to Los Angeles, California where he entered UCLA for a master’s degree. In Los Angeles, Long met Bill, a location manager for Hollywood movies. Bill smiles as he recalls that first chance meeting in a gym, when he asked Long about the t-shirt he was wearing that said “Thailand.” Bill’s eyes get a little misty. “The best thing that ever happened to me,” he says. In 2010, Long had the opportunity to continue pursuing his path in medicine at OHSU. He and Bill moved to Portland. At OHSU, Long began his career as a Nurse Practitioner, eventually settling into the specialty Pain Management.

While working on a cardiac ward, he met Mark Stave, a nurse, and, it turned out, a Mazama.

Long had first experienced climbing back in Asia. In Colorado, he hiked a few “14-ers.” But the Northwest’s Cascades offered what Long considered “real climbing”—long-distance approaches, setting up a base camp, and crossing glaciers ripped by crevasses.

He took the Basic Climbing Education Program (BCEP), and a couple years later the Intermediate Climbing School (ICS). Climbing with Mazamas gave Long a community of “like-minded” people who shared his passion for climbing and his love of

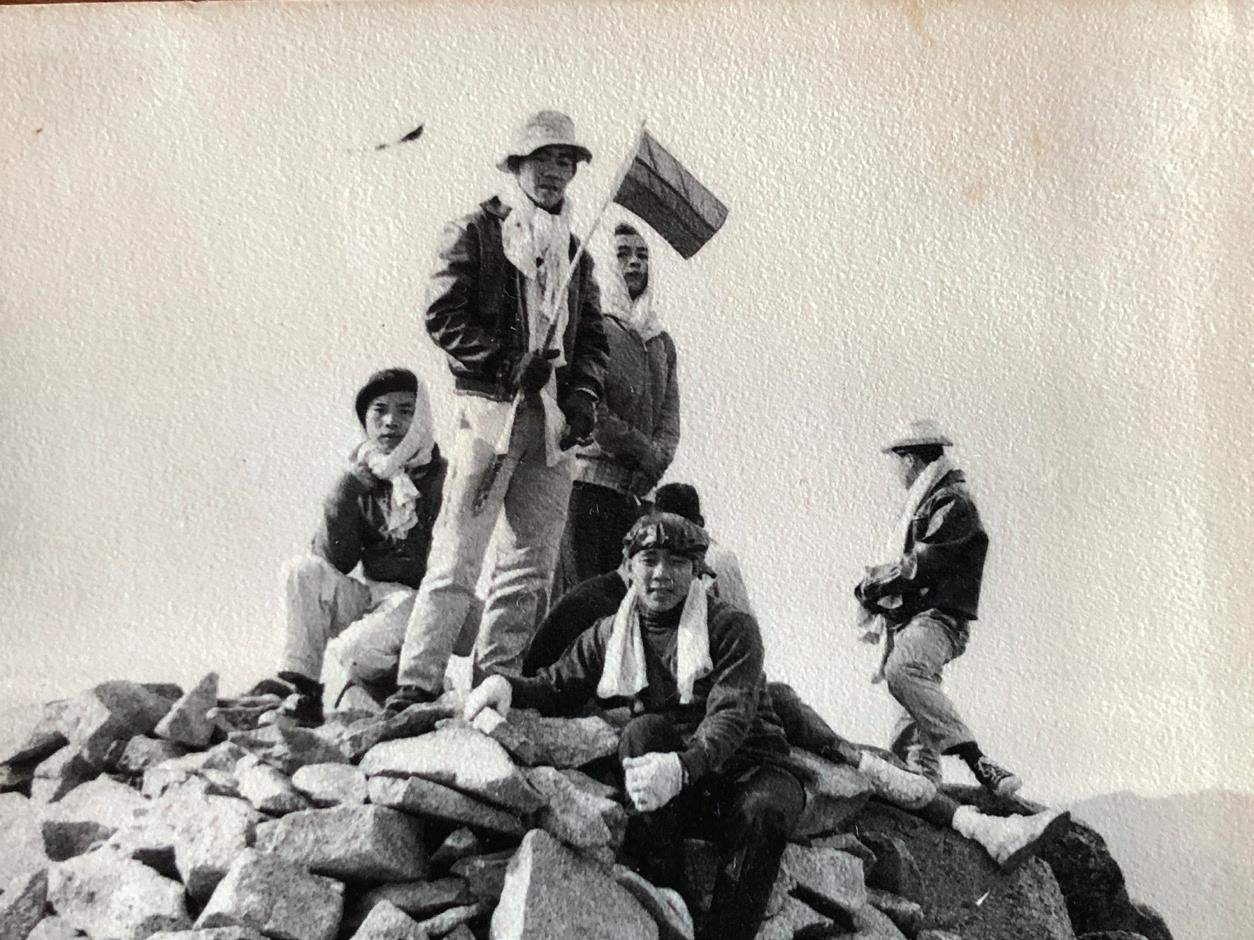

Yunlong’s dad and friends on the summit of Borneo’s Mt. Kinabalu, 1966

nature. Having been focused intensely on his academic studies for years, Long could enjoy a new chapter of alpine adventure and camaraderie.

In 2016, he decided to take the final step and enter the Mazama Leadership Development program to become an official Mazama climb leader.

In August 2018, Long had reached his third provisional climb. Never settling for easy, he’d picked North Sister. I was fresh out of

BCEP that spring and applied for his climb. Rather than reject me flat out, Long called other climb leaders for a reference. Running background checks like this would later become one of Long’s standard practices as a climb leader.

On that climb, I got to witness his leadership style. “He tries to get everyone involved in the climb,” says Mark Stave. “I think that makes for a very strong team when everyone feels like they are not just along for the ride.”

Long successfully completed this final provisional, completing the requirements to apply to become a Mazama climb leader. Barely a month later, Long stood on the summit of Africa’s fabled Kilimanjaro. That same day he learned that he had been approved as a climb leader. Long’s life had reached a true high point.

Before heading back to the U.S., he flew to Singapore to celebrate his dad’s 80th birthday. He had lots of success to report, yet he had one concern that he’d have to deal with when he got back home that he kept to himself. He didn’t want his dad to worry.

“Why is dad so thin?” he asked his mother.

His mother hadn’t noticed. “When you see someone every single day, you don’t notice the gradual changes,” said Long.

Before he left, Long said to his younger brother, “Look after dad.”

Critical Juncture

Before Long left for Africa, he had experienced gastrointestinal bleeding. His doctor had scheduled an endoscopy for after his return.

The endoscopy revealed two ulcers. His doctor took a biopsy. When Long saw the image, with his medical training he could see that the cells did not look normal.

Three days later, the test results confirmed what he’d feared.

“That’s when my world fell apart,” he said.

He turned to his partner, Bill. “We had to decide what we would do at this critical juncture,” Long said.

There was so much uncertainty ahead. “What was certain,” said Long, “We love each other. We want to spend this time together.”

A few days after Thanksgiving 2018, they gathered a small group of friends, some of Bill’s family, and a minister. They exchanged vows. They were declared “husband and husband.”

For him to marry a man was “beyond comprehension” in the culture Long had grown up in. “The opportunity to say that you love someone, of the same gender,” explained Long. “You can be who you are, not what you are.”

Setting His Sights High

At the beginning of 2019, Long started his first round of chemo. But soon after, he flew back to Singapore.

His Dad was having health problems. It started with pneumonia, but had worsened to a delirium where he didn’t know where he was and could not even recognize family members. But when Long went to visit him in the hospital, his dad recognized him and asked, “Why do you have no hair?”

“Oh, it’s a new fashion,” said Long, not wanting to worry his father.

That spring, Long underwent his second round of chemo and resection surgery. Then he flew back to Singapore again, this time for his dad’s funeral.

Long’s body was pummeled by more rounds of chemo. And when the last round was done, he turned his sights to mountains.

Starting with Jefferson, he charged six summits, apologizing to his team for being, “a little slower than usual.”

“I’ve only seen him frustrated once,” says Daven Berg, climbing partner and friend. They were coming down North Sister. After

Yunlong on Kilimanjaro. Photo by Daven Berg.

some 13 hours since the alpine start, a day of setting lines and keeping a watchful eye on his team, Long was exhausted and beginning to fall behind. Daven was ahead with the others when he heard a noise come from Long. “It wasn’t a word, and it wasn’t aimed at anyone, but just like a yell up at the sky, just an expression of frustration out loud,” Daven explains. “It wasn’t a theatrical display to draw attention to himself, just a moment. A moment where I realized he was human.”

“Then, he was back to his jovial self.”

Long’s blitz climbs of 2019 might have seemed like a frantic dash to fill every weekend with a climb—going against the common sense to rest and recover after such an intensive medical ordeal and painful loss of his father—but Long had a plan with deeper purpose.

He had to rebuild his body’s iron levels from the massive blood loss. He wasn’t just scrambling up the familiar Cascades for pure fun—every foot upward was training.

He charged to the end of the climb season, then headed south to Mexico. He climbed two mountains, 17,343-foot Iztaccihuatl and 18,491-foot Pico De Orizaba. But even these peaks were training for his real goal of 2019.

He had climbed Africa’s highest peak with his friend Sue, from Singapore. Now they’d set their sights on the highest peak in the Americas, Aconcagua. Rising 22,838 feet above sea level in the Andes of Argentina, it is the highest peak outside the Himalayas. To pick such a superlative summit was fitting for such a difficult year.

South America had held a special place in Long’s imagination. “It had a mystique,” he said. “It felt exotic, like a true adventure.”

After his string of summits, Long felt strong again. Ready.

Transcendent Loneliness

Climbs always seem to start loud, and eventually get quiet.

This is what Long seeks. “A pure communion between human and mountain, uninterrupted by other human beings,” he said. “I seek the pureness and the transcendent loneliness of the mountain, the mountain breeze that seems to blow away my worries and the pure elation of entering a relationship with the mountains.”

When Long goes on climbs, like our Jefferson climb, he slips away from the group for a moment. “I have some business to take care of,” he’ll say, making a joke about using a blue bag. Which is actually true. But under his potty humor, there’s his spiritual side. He’ll step away from the team to say some prayers in private.

Reaching the summit of Aconcagua was the highest he’d ever been on the planet. Being so high above the world of cities and roads and schools and hospitals, put him closer to a spiritual plane, “energy that we can’t fully understand,” he describes.

When he is on a mountaintop, Long stops to think about his dad. He keeps a snapshot taken when his dad was a young man, proudly standing with a team on the talus peak of Mt. Kinabalu back in Borneo.

Long recalls the last time he saw his dad in the hospital in Singapore. “Before he died, I sensed he was proud of me,” says Long.

He offers the wind a prayer. “Dad, wherever you are, I hope I am your pride and joy. I hope you are in a good space. Thank you for giving me this life to do this climb.”

When Long first moved to America, his dad was worried about his son. “Does he have enough money, someone to take care of him?”

When Long says his mountaintop prayers, he tells his dad, “Don’t worry about me.”

More Peaks Than a Lifetime

Long beat his cancer into remission, but it returned. He resumed the rounds of chemo. He got good news, then bad news, then good news, then more bad … as it too often goes with the cruelty of cancer.

But he doesn’t want to focus on the disease—rather, on resiliency. Thinking about the mountains he will climb gives him something to look forward to. “The life-motivating desire to scale every mountain I can possibly do so with my finite time in this mortal world!”

“As a health-care provider, he’s aware of his prognosis,” says Mark Stave. “I think he’s realistic, but he doesn’t let the diagnosis of cancer hold him back. These are goals he had pre-cancer, and he’s not going to let cancer take those dreams away from him.”

By the end of 2020, Long had set his sights on returning to South America to attempt three large peaks in Ecuador—Cayambe, Cotopaxi, Chimbarazo. He invited Mark and Daven to join.

Long feels drawn back to the Andes. “There are more peaks than we’ve heard of there, the expanse of the unknown,” he says. “Standing on a summit, you can see more peaks than anyone can climb in a lifetime.”

But that won’t stop Long from trying.

Yunlong on the summit of Mt. Shuksan. Photo by Daven Berg.