MARCH/APRIL 2022 1

ME E T T HE CHALLE NGE S OF ICE AND SN O W At last, the first freeze. The landscape changed. Obscured. But the restless see new routes revealed. The possibilities of winter, fresh footprints, and untouched lines. Demanding, fickle and often fleeting, nothing offers challenge like the winter season. We’ve designed our range to help you thrive in this hostility, to embrace the opportunities of winter head on.

W W W .RA B .E Q U IPME N T

2 MAZAMAS

MAZAMA BULLETIN

IN THIS ISSUE Interim Executive Director’s Message, p. 4 President’s Message, p. 5 Mazama Values, p. 6 Upcoming Courses, Activities, & Events, p. 7 COVID-19 Policy Update, p. 8 Mazama First Aid Committee, p. 9 Mazama Leadership Development, p. 12 Farewell to Oregon’s Central Cascade Glaciers?, p. 15 Backcountry Ski Leader Profile: Mike Myers, p. 19 Musical Mountaineers, p. 20 Climb Leader Profile: Guy Wettstein, p. 22 Hiking with Athena, p. 23 A Brief History: Mazama Ski Mountaineering , p. 25 The Thrill of the Climb, p. 28 Mazama Nominating Committee, p. 28 The End of an Era, p. 29 Jack Grauer, p. 30 Saying Goodbye, p. 32 The Messiest Grade, p. 34 Successful Climbers, p. 37 Executive Board Minutes, p. 38 Mazama Lodge, p. 39 Cover: Jack Grauer on Mt. Constance, 1964. VM2012.007 Nick Dodge Collection. Above: New member Emily Bonner on the summit of Mount St. Helens, April 18, 2021.

Volume 104 Number 2 March/April 2022

CONTACT US Mazama Mountaineering Center 527 SE 43rd Ave., Portland, Oregon, 97215 Phone: 503-227-2345 | help@mazamas.org Hours: Monday–Thursday, 10:30 a.m.–5 p.m. Mazama Lodge 30500 West Leg Rd., Government Camp, OR, 97028 Phone: 503-272-9214 | mazamalodge@mazamas.org Hours: Friday–Sunday, 9 a.m.–10 p.m., Monday, 9 a.m.–Noon PUBLICATIONS TEAM Editor: Mathew Brock, Bulletin Editor (mazama.bulletin@mazamas.org) Members: Brian Goldman, Darrin Gunkel, Ali Gray, Ryan Reed, and Claire Tenscher (publications@mazamas.org)

MAZAMA STAFF mathew@mazamas.org

KALEEN DEATHERAGE Interim Executive Director kaleendeatherage@mazamas.org

RICK CRAYCRAFT Facilities Manager facilities@mazamas.org

BRENDAN SCANLAN Operations & IT Manager brendanscanlan@mazamas.org

MATHEW BROCK Library & Historical Collections Manager

For additional contact information, including committees and board email addresses, go to mazamas.org/contactinformation.

MAZAMA (USPS 334-780): Advertising: mazama.ads@mazamas.org. Subscription: $15 per year. Bulletin material must be emailed to mazama. bulletin@mazamas.org. The Mazama Bulletin is currently published bi-monthly by the Mazamas—527 SE 43rd Ave., Portland, OR 97215. Periodicals postage paid at Portland, OR. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to MAZAMAS, 527 SE 43rd Ave., Portland, OR 97215. The Executive Council meets at 4 p.m. on the third Tuesday of each month. Meetings are open to members. The Mazamas is a 501(c)(3) Oregon nonprofit corporation organized on the summit of Mt. Hood in 1894. The Mazamas is an equal opportunity provider.

MARCH/APRIL 2022 3

INTERIM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE by Kaleen Deatherage, Mazama Interim Executive Director

D

ear Mazama members, donors, and friends of the mountains, hello and happy new year from all of us at the Mazamas! You know that old adage we’ve all heard many times; the only constant is change. It feels as relevant today as it ever has. We have greatly appreciated your patience as we navigated the COVID-19 pandemic the past two years, and then more recently as we’ve undergone organizational transitions with the departure of Sarah Bradham, our Acting Executive Director, Monika Lockett, our Camp Manager, and Katherine Rose, our Volunteer Coordinator. Their contributions were significant, and we thank them for their service to the Mazamas.

I am honored to have the opportunity to serve you as the Mazama Interim Executive Director. This organization has a deep history, not only in our Cascade mountains, but also in the stories of those who have adventured in them. Your stories span decades, add to the deep historical record of our region, and have helped to make the Mazamas a mainstay of the outdoor community. All organizations must adapt and evolve to stay relevant and the Mazamas is no exception. Right now, it’s time to look inward to clarify and unify around a vision for our organization’s future. Together, we need to make many important decisions, key among them; who can become a member moving forward, who can serve in leadership roles, and what kind of programs will we offer. Most importantly, we must find a path to a more sustainable future. One thing is abundantly clear to me already, we need to significantly expand the revenue pipeline for the Mazamas. We can’t sustain even a scaled-down organization on the funding sources we currently rely on. So how do we go about charting this path? We’re approaching 2022 as a rebuilding year. Over the next few months, the Mazama Board of Directors, working with our staff and committees, is committed to the task of addressing the business side of the Mazamas. It’s time to chart a new strategic roadmap that will guide the programs and deliver the mission of our organization for the next three to five years. We’ll be looking at how to make our programs and activities more profitable, re-evaluating our budget process and how we engage with committees, and 4 MAZAMAS

evaluating nonprofit funding sources to expand our revenue generating potential. If the Mazamas choose to make the hard business decision to open our membership to a broader range of individuals, we then position the organization to pursue public and private grants, donor-advised funds, and capital gifts that our current bylaws make us ineligible to compete for. Changing our membership requirements not only makes sense from the standpoint of becoming more fair and inclusive, it’s also a sound business decision and one I believe is key to this organization’s survival. We’re also going to navigate this year by scaling back a bit. We’ve made the hard decision not to offer our Mazama Wild Camp this summer. Youth programming is an important pillar of the Mazama mission of getting everyone outside loving and protecting the mountains. The Mazama Wild Camp exposes hundreds of young people to the wonders of the natural world, the thrill of rock climbing, and the wild of the mountains. Knowing how important this program is to fulfilling our mission, the staff and board met multiple times to explore every possible path to offering our Mazama Wild Camp this summer. Those efforts, sadly, did not result in our concluding that we have a viable path to run camp this year, and so we are postponing Mazama Wild for 2022. We are firmly committed to re-opening Mazama Wild in 2023 and celebrating our tenth summer welcoming campers to experience their urban and wild environments through hands-on science experiments, nature lessons, climbing, hiking, and play.

While doing all of this, we will continue to offer the programs and classes that are a mainstay of the Mazamas. BCEP is already full with a waitlist, and most of our other classes are also expected to fill to capacity, which reminds us of the interest our community has in getting outdoors and exploring the mountain landscapes we all love. Interested in learning a new skill this year? Check out our website and find the educational opportunity, event, or activity that will take you on a new adventure. Even better, bring a friend to the Mazamas and enjoy the adventure together! I’m looking forward to getting input from all of YOU, our stakeholders, as we collectively define our vision of the future, think about the make-up of the organization, and determine the type of leader who can guide the Mazamas towards that bright future in 2023 and beyond. We’ll be holding a couple of townhall-style listening sessions on March 14 and 22. Be on the lookout for the invitation and please consider giving a little bit of your time and energy to help us choose the route our organization will follow in the years to come. The Mazamas has always counted on YOU—its friends and members—to make this great organization go. We are excited to dream and plan alongside you over the next several months to arrive at a vision that will guide our decisions, bring about greater sustainability, and strengthen the Mazamas for years to come. Portland will always need what the Mazamas can deliver like no one else— a path to experience, love, and protect the mountains.

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE by Jesse Applegate, Mazama President

W

hat if I told you the Mazamas is going out of business? Would you believe me? Would you wonder what that means–especially since our programs are volunteer-led? Well, it’s true. If we continue doing everything we currently do, as we have been, the Mazamas will cease to exist in the not-so-distant future. Why? And what do we do about it? First, I’ll make some assumptions. I assume you, as a member or participant in our community, care and wish to change our course from its current outcome. Without you, the Mazamas will be only history. Second, I assume you don’t necessarily have enough information to understand what needs to be done. Let me help you. The Mazamas: is it a business or social organization? It’s both. Yes, most of our programs are volunteer-led, and the experiences we have participating in those programs give us that sense of community that keeps us coming back. However, we have infrastructure to support all those volunteer-run programs in the form of real property, i.e., the Mazama Mountaineering Center (MMC) and Mazama Lodge, maintenance, group gear, custom website, database, insurance, permits, business relationships with other organizations, cloud services, bank accounts, investments, telephones, bills, etc. Most importantly, among us are people (staff) to help us run all of these things. They answer questions, help us operate the website when we don’t want to figure it out ourselves, and they also participate in the same Mazama programs we all love. Just as your household needs money to exist, the Mazamas does too. What’s the phrase: “no money no mission?” So, what’s our business plan? We rely on only a few revenue sources including membership dues, program and activity fees, and donations. “But we’re a nonprofit, what about grants?” you may ask. Unfortunately, we’re not eligible for most grants available to public benefit nonprofits because of our institutional structure. How else can we support ourselves? The obvious conclusion is to increase membership. However, we can’t easily increase our membership because of the glaciated peak membership requirement in our bylaws. In many cases, the glaciated peak requirement is not only holding back our membership potential, it’s also preventing us from applying for and receiving the grants mentioned above.

Perhaps you’ve heard this all before. That’s because it’s a conversation that’s been happening periodically for a long time. The difference now is that we are, and have been, consuming our investments and we will no longer have them to rely on in the future. We must find a way to be sustainable. There have been many well-intended efforts in the past to adapt, but they have for the most part been thwarted by our institutional structure defined in our bylaws and operating policies. There is no single position of institutional stability in how we’re structured. We don’t have a permanent finance director, a financial professional who keeps us operating to standard business practices, has their thumb on how we’re operating, can predict our needs, and makes recommendations before it’s too late. We have a new board makeup every year, new board officers every year, and our staff turnover is high. We’ve seen over and over that investments of time and money in programs and policies take longer than a year before they’re fully established and can bring results. With each new election cycle we get a new board, new leadership, and new ideas about the direction of the organization. Often, the new leadership is unfamiliar with the previous direction and there may be little to no sharing of institutional knowledge from one leader to the next. The average lifespan of volunteerism in the Mazamas is about seven years for a given person. These instabilities are baked into our bylaws, which is why there was so much effort to change them recently. Unfortunately, the message communicating the need to change was not received by enough of us.

So, here we are, continuing on a path that, without a correction, will likely lead to an insolvent dead-end. While we still have options, we need to determine who we are and what we want for the future of Mazamas. The path forward will not be easy as we have some difficult decisions to make. It will take all of us to help organize, take ownership, and participate in making our nonprofit business healthy, solvent, and stable so that the Mazamas community can survive and thrive. We can find solutions to the problems that are in front of us and we can do this best, if we do it together. I encourage all of you to learn about how our business works, what could be better, what should change, and why. To facilitate that sharing and to listen to your input and ideas, the Executive Council along with Kaleen, our Interim Executive Director plan to host two online forums in March, tentatively on the evenings of March 14 and March 22, 2022. We'll come ready to share our thinking about priorities for Mazamas and we want to listen to yours. More details will follow in the eNews and on the mazamas.org website. Please plan to attend one of these sessions and contribute your best thinking to the future of our great organization.

MARCH/APRIL 2022 5

MAZAMAMEMBERSHIP DECEMBER Membership Report NEW MEMBERS: 21 Melinda Becker, South Sister Gina Binole, Mount St. Helens David Blanchard, Mt. Hood Connor Carroll, Mount St. Helens Stephen Deatherage, South Sister Olivia Glassow, Mount St. Helens Julie Hakes, Mount St. Helens Lena Hanschka, Mt. Buet (France) Eli Hanschka, Mt. Shasta Frank Hoffman, South Sister Nathan Jundt, South Sister

Darren Lee, Mt. Hood Rachel Nelson, South Sister Stephanie Podasca, Mt. Adams Caleb Rabe, Mount St. Helens Kristina Rheaume, Mount St. Helens Susan Scholefield, South Sister Matt Smith, Mt. Hood David Taylor, Mount St. Helens Michael Thomas, South Sister Donald Wright, Mt. Hood

REINSTATEMENTS: 7 DECEASED: 2 MEMBERSHIP ON DECEMBER 31: 2,480 (2021); 2,537(2020)

NEW MEMBERS: 58

REINSTATEMENTS: 15 DECEASED: 2 MEMBERSHIP ON JANUARY 31: 2,579 (2022); 2,591 (2021) 6 MAZAMAS

SAFETY

We believe safety is our primary responsibility in all education and outdoor activities. Training, risk management, and incident reporting are critical supporting elements.

EDUCATION We believe training, experience, and skills development are fundamental to preparedness, enjoyment, and safety in the mountains. Studying, seeking, and sharing knowledge leads to an increased understanding of mountain environments.

VOLUNTEERISM

JANUARY Membership Report Agreen Ahmadi, Mt. Damavand (Iran) Paul Anderson, South Sister Alicia Antoinette, Mount St. Helens Joshua Robert Baker, Eagle Cap Sarah Bellamy, South Sister Emily Bonner, Mount St. Helens Tim Brodovsky, Broken Top George Burwood, Mount St. Helens Riley Carey, South Sister Kelly Chang, South Sister Michael Costello, South Sister Jennifer Costello, Mount St. Helens Kimberly Crihfield, South Sister Jonny Cushing, Mount St. Helens Brian Davis, Mount St. Helens Mario DeSimone, Mount St. Helens Fern Elledge, South Sister Camilla Elven, Mount St. Helens Jennifer Eykamp, Mount St. Helens Andrew Haertel, Mt. Shasta Brian Hague, Mount St. Helens Mikhail Hakim, Mt. Rainier Leah Harrison, Mt. Adams Jeannine Hart, South Sister Gass Hersi, Mt. Whitney Ben Hoffman, Mt. Hood Lisa Hughes, Mt. Rainier Mikael Jackson, Aconcagua (Argentina) Jon Kennedy, Mount St. Helens Sumanth Krishnamurthy, Mount St. Helens

MAZAMA VALUES

Lukas Kubeja, Mt. Adams Guy La Salle, Mount St. Helens Noah David Levinson, Mount St. Helens Jessamyn Luiz, Mt. Whitney Tovah Maas, Old Snowy Mountain Julie A Maas, Old Snowy Mountain Michael Maier, Mt. Hood Ada Marie, Old Snowy Mountain Derek Markee, South Sister John Milward, Breithorn (Switzerland-Italy) Paresh R Nawale, Mount St. Helens Alexander Pelka, Mount St. Helens Anthony Pucci, South Sister Peeyush Purohit, Mt. Adams Jonathan Robinson, Mount St. Helens John Rowland, Mount St. Helens Brooke Schiefelbein, South Sister Andy Schultz, Mt. Adams Sharon Selvaggio, Mount St. Helens Jenna Nicole Shockley, Mt. Kilimanjaro (Tanzania) Gabriela Sisco, South Sister John Ste. Marie, Mount St. Helens Jonathan Todd, Mt. Hood Elizabeth Tomczyk, Mt. Hood Thomas Richard Veeman, South Sister Mike Wills, Mount St. Helens Brian Wisner, Gilbert Peak Sean Wuilliez, South Sister

We believe volunteers are the driving force in everything we do. Teamwork, collaboration, and generosity of spirit are the essence of who we are.

COMMUNITY We believe camaraderie, friendship, and fun are integral to everything we do. We welcome the participation of all people and collaborate with those who share our goals.

COMPETENCE We believe all leaders, committee members, staff, volunteers, and participants should possess the knowledge, skills, abilities, and judgment required of their roles.

CREDIBILITY We believe we are trusted by the community in mountaineering matters. We are relied upon for information based on best practices and experience.

STEWARDSHIP We believe in conserving the mountain environment. We protect our history and archives, and sustain a healthy organization.

RESPECT We believe in the inherent value of our fellow Mazamas, of our volunteers, and of members of the community. An open, trusting, and inclusive environment is essential to promoting our mission and values.

UPCOMING COURSES, ACTIVITIES, & EVENTS WILDERNESS FIRST AID: SPRING SESSON 1

HELLS CANYON OUTING

■ Dates: June 4 ■ Registration Opens: April 26 ■ More Info: tinyurl.com/MazWFA221

■ Dates: Apr. 24–30 ■ Application Closes: April 6 ■ More Info: mazamas.org/outings, “Mazama Outings” on page 12

WILDERNESS FIRST AID: SPRING SESSON 2

ALASKA HIKING OUTING

■ Date: June 5 ■ Registration Opens: April 26 ■ More Info: tinyurl.com/MazWFA222

■ Dates: August 17–24 ■ Application Closes: June 1 ■ More Info: mazamas.org/outings, “Mazama Outings” on page 12

UPCOMING PERMIT DATES MOUNT ST. HELENS ■ April 1–May 14: 300 climbers per day, $15 per person with $6 transaction fee, purchased in advance online at recreation.gov ■ May 15–October 31: 110 climbers per day, $15 per person with $6 transaction fee, purchased in advance online at recreation.gov DOG MOUNTAIN

DEATH VALLEY OUTING

■ Date: Apr. 3–10 ■ Application Closes: March 15 ■ More Info: mazamas.org/outings, “Mazama Outings” on page 12

STREET RAMBLES

CANYONEERING 2022

■ Application Opens: April 18 ■ Application Closes: May 2 ■ More Info: mazamas.org/canyoneering This six-week course includes weekly lectures and two field sessions. The lectures will provide an overview of canyoneering, introduce canyon-specific topics and techniques, and prepare students for the class field sessions. An optional, latesummer outing will be offered to course graduates. The class will focus on local canyoneering in the Pacific Northwest, but we will touch on some aspects specific to the sandstone canyons of the Colorado Plateau.

Going on a Street Ramble is one of the best ways to get an introduction to the Mazama hiking program. Meet other hikers and plan a weekend trip, maintain your fitness after work, and see some hidden parts of Portland you might never get to see otherwise. Interested in joining us? All you need to do is show up, check in, pay, and be ready to go at 6 p.m. We'll see you there! We operate Tuesday and Thursday night Street Rambles year-round from REI in the Pearl District (NW Portland). More info at mazamas.org/rambles.

■ Permits for the Dog Mountain Trail System are required on Saturdays and Sundays between April 23 and June 12, 2022, and Memorial Day (May 30, 2022). There are 200 permits per day available for online reservation. Half of these will be released March 1 and the remainder will be available online three days in advance. Permits will also be available on a first-come, first-serve basis for visitors using the Dog Mountain shuttle (operated by Columbia Area Transit). ENCHANTMENTS

■ Between May 15 and October 31, a permit is required for overnight use in the Enchantments. Permits allow the permit holder and their group to camp overnight in one of the five zones: □ Core Enchantment Zone □ Snow Lake Zone □ Colchuck Lake Zone □ Stuart Lake Zone □ Eightmile/Caroline Zone CENTRAL CASCADES

■ At the time of this publication going to print, the permit starting date hadn’t been updated, but it looks like May 27 will be the start based on last year’s date.

MARCH/APRIL 2022 7

COVID19 POLICY UPDATE by Risk Management Committee

I

n order to stay current with local and federal recommendations, members of the Mazama Board, staff, and the Risk Management Committee reviewed and revised the Mazama COVID-19 Policy. Significant updates to the policy are highlighted below. All participants of Mazama activities should be familiar with this policy.

PROOF OF VACCINATION

The new policy expands the proof of vaccination requirement for indoor activities at the Mazama Mountaineering Center (MMC) and the Mazama Lodge to all eligible groups. Anyone age 5 or older must be vaccinated for COVID-19 to participate in INDOOR programming at the MMC or Mazama Lodge. Anyone participating indoors will have to present proof of vaccination. To apply for a vaccine badge to be added to your profile, please visit mazamas. org/covid19vaccinebadge. CAPACITY RESTRICTIONS

The new policy lifts capacity requirements at the MMC and the lodge. With the lifting of the State of Oregon’s Sector-Specific Risk Framework in the Summer of 2021, at this time there are no longer capacity restriction, or caps on the number of individuals permitted to occupy these spaces at any one time, with regard to the use of these facilities. Additionally, physical distancing between individuals from different households will no longer be strictly enforced at the MMC or the Mazama Lodge. However, understand that physical distancing is still a viable means of reducing transmission of COVID-19. To that end, we ask all of our Mazama members, staff, volunteers, participants, and/or guests to be mindful and respectful of others with regard to the distance separating them from others when interacting. Please keep in mind limited staffing exists at these facilities and special consideration should be given to this fact if you plan to have large group activities. Please be patient and considerate of staff. Neither of these facilities has had large groups in almost two years, and this policy adjustment 8 MAZAMAS

will likely impact staff and users. Without additional volunteer support and/or a short-term staffing plan that is worked out with the Executive Director and staff of the facility before booking, we may not be able to accommodate larger groups. We appreciate your ongoing patience and consideration of staff as they work to open our facilities to as many users as is safe and feasible. VACCINATION BOOSTERS

The Mazamas are not yet requiring vaccination boosters. While the CDC’s definition of fully-vaccinated has not changed, studies have shown that after getting vaccinated against COVID-19, protection against the virus and the ability to prevent infection with variants may decrease over time. Additionally, the recent emergence of the Omicron variant further emphasizes the importance of boosters needed to protect against COVID-19. In light of recent updates to the CDC’s quarantine guidelines for those fully vaccinated having had close contact exposures with confirmed COVID-19 positive cases, and to ensure that the Mazamas can successfully operate group classes and ensure business continuity and operations, a vaccination booster for qualified individuals is recommended, but not required, for participation in INDOOR programming, activities, or events at the MMC or Mazama Lodge. Whether or not an individual has received a booster is an important consideration when deciding whether or not to quarantine. QUARANTINE REQUIREMENTS

For individuals NOT fully vaccinated AND boosted If you live with, or have had confirmed close contact (i.e., within 6 feet of distance for a cumulative time of 15 minutes or longer in a 24-hour period), with

anyone who has symptoms of COVID-19 (see policy), is awaiting test results for COVID-19, or was diagnosed with COVID-19 in the last five days, AND you are NOT fully vaccinated AND boosted: ■ You are not permitted to participate in a Mazama activity or event, or enter the MMC or Mazama Lodge, for a period of 5 days post-exposure, regardless of the outcome of any COVID-19 tests. ■ Please notify the activity or event leader or designated contact to notify them and plan on not attending. Staff at the Mazamas will ensure that you receive a full refund. Please contact the office at 503-227-2345. ■ If the individual with whom you had exposure is solely symptomatic, and ultimately tests negative for COVID-19, you are permitted to once more participate in Mazama activities or events, or enter the MMC or Mazama Lodge. For individuals fully vaccinated AND boosted If you live with, or have had confirmed close contact (i.e., within 6 feet of distance for a cumulative time of 15 minutes or longer in a 24-hour period), with anyone who has symptoms of COVID-19 (see policy), is awaiting test results for COVID-19, or was diagnosed with COVID-19 in the last five days, and you ARE ANY of the following: ■ Fully vaccinated AND boosted; OR ■ Vaccinated but not yet eligible for a booster dose; OR ■ Have recovered from a confirmed COVID-19 positive case in the past 90 days; AND ■ You are not experiencing any of the symptoms noted in the policy, Then you are permitted to continue participating in the Mazama activity or event. It is recommended that you monitor

yourself closely for the development of any new signs of illness over the next 10 days and notify your Mazama activity or event leader immediately if your health status changes. It is also recommended that you seek out COVID-19 testing three to five days postexposure. Please assist us in reducing the spread of COVID-19 in the following ways: ■ Get vaccinated and boosted (if eligible); ■ Wear a well-fitting mask, preferably an N95 or KN95; ■ Stay home when sick; ■ Stay away from people who are exhibiting signs or symptoms of illness;

■ Cover your coughs and sneezes and wash your hands with soap and water often; ■ Maintain distance from people outside of your home; and ■ If needed, contact your primary healthcare provider to determine if testing may be advised. For more information, please call 211. Special thanks to Kyle DeHart and Sari Hargand for lending their experience and time to this effort. If you have any questions or concerns about this new policy please contact Kaleen Deatherage (kaleendeatherage@mazamas. org) or Greg Scott (gregscott@mazamas.org).

MARCH/APRIL 2022 9

CANYONEERING

IN THE NORTHWEST

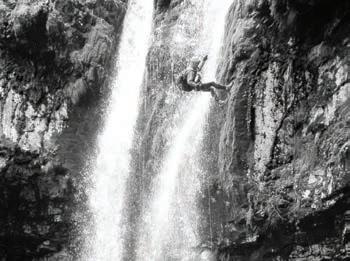

Above: Wim Aarts in the flow of a 150 foot rappel.

by Wim Aarts

W

hat class? Canyoneering in the Northwest you say? Is that even a thing? These are questions that I want to answer in this article and why canyoneering is such an amazing activity and experience.

The newest of the standing yearly classes within the Mazama education spectrum, canyoneering, was established six years ago. Numerous Mazamas have been to the deseret Southwest, to places such as Zion National Park and the canyons of the Robbers Roost and Escalante in Utah. When told about the amazing possibilities of the desert Southwest, one of the Canyoneering Committee founders, Keith Campbell, answered simply; “Oh, I do that kind of thing here all the time.” Not really convinced, some of us started joining the canyoneering scouting trips in the Northwest to see it with our own eyes. Soon, the list of canyons became extensive and it became clear that there are so many hidden slots to be descended in our area. At just about the same time, a number of 10 MAZAMAS

Seattle-based folks got into scouting in Oregon and Washington, which developed into great cooperation and friendships. The latest Mountaineers annual canyoneering meeting was attended by members of the Mazama Canyoneering Committee, and we taught a short lecture on retrievable anchoring systems. Canyoneering (or canyoning) is a fastgrowing sport in the Pacific Northwest (PNW). What makes it so exciting? The PNW is blessed with humidity— rain anyone?—and this makes for very lush and wet canyons in contrast to the Southwest desert canyons. And let’s face it, Utah adventures are special and can be fantastic, but they take considerable travel time. Within a couple of hours of Portland, we have dozens of very cool

canyon descents that now also have good descriptions available online on websites such as ropewiki.com. What is so difficult about rappelling some wet and cold “ditches” in the woods, you might ask? The answer might surprise you in that it’s not really that complicated if and when basic safety considerations are taken into account. Slippery when wet: A basic fact is that rappelling in waterflow and on slippery, mossy rock takes special precautions. It takes the right protective gear to avoid hypothermia or loss of control of the rappel due to the wetness and the cold, and you need to be prepared for the impact of a firehose of cold water and

continued on next page

Canyoneering, continued from previous page obstacles such as brush and tree trunks in the flow. Approaching canyon waterfalls almost always includes some steep off-trail hiking and navigation challenges. Creek walking, often very spectacular, takes the right gear and focus. This is a sport where you can experience overheating and hypothermia during the same trip—hat’s not to love? In the canyoneering class, you’ll learn and practice rappelling techniques with specialized descenders which are designed to change friction settings while rappelling. As an added bonus, we teach climbers to rappel right off the end of the

rope into pools. Anchors, that in the desert Southwest mostly consist of bolts or cairns, will in this area often be attached to trees. Retrieving your rope and pull cord for your next descent, is done with specialized techniques and tools. If you are interested in hanging on rappel in a lush green canyon, swimming narrows, jumping into pools (after verifying and scouting), or getting to places that are not accessible in any other way, this class is exactly what you’re looking for. Sign-up for the May through July 2022 class will start in March 2022, watch the weekly eNews for updates.

Left: Rappelling Covell Falls. Above: Rappelling into the Rain Room in Big Creek. Photos submitted by Wim Aarts.

by saRah Busse I would like to express what fills my heart with joy and terror, uses all my skills for ropework and safety, as well as brings me to an amazing adventure in the woods with only my teammates to help me. I feel canyoneering has really given me such a special gift of adventure that so many people don't even know exists. Imagine you are in the movie Avatar, this is what I think of when I am canyoneering in the Pacific Northwest. You exit the busy trails crowded with people trying to get away on the weekend and are transported to a magical lush green forest with ferns as tall as your shoulders and clear cold water dripping off the canyon walls feeding the walls of hanging greenery. You exit your car with this strange gear hanging off you and disappear into the forest, bushwhacking through an area that not many people have seen. It is this magical experience that is hard to describe until you experience it. Through canyoneering, I have learned so many tips and tricks for improved safety, comfort while quickly ascending ropes, quick problem solving, efficiently making anchors and rappelling, and downclimbing techniques. These are skills used regularly in canyoneering that have greatly improved my alpine and rock climbing skills. When you drop into a canyon, there is usually only one way out and that is down. You and your teammates must work together as a team to safely get out. This is what I love about canyoneering and as leaders, we would love to share that with you. MARCH/APRIL 2022 11

MAZAMA LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT

DON’T SEE CLIMBS THAT YOU WANT ON THE CALENDAR?

Members of the Leadership Development team pause for a break on the Zipper, Lane Peak. Photo by Suresh Singh.

by Leora Gregory, Leadership Development (LD) program manager

I

f you’ve already garnered some climbing experience, you might be able to help us help you by becoming a climb leader yourself ! HERE’S HOW IT WORKS.

The Mazamas has a largely experiential Leadership Development program where you can try out leadership roles and get mentorship in a safe environment, i.e., with someone who is already a climb leader. If you’re not into dealing with ropes, you can join the program to focus on A-level climbs. If you’re more interested in higher-level climbs, then the program also lets you develop teaching skills for those techniques necessary to make the inherently unsafe act of climbing as safe as it can be. Teaching the skills allows others to evaluate whether you know the skills well enough for leadership, and also helps promote the act of passing on the knowledge that people come to the Mazamas to learn. SO, WHAT’S ACTUALLY INVOLVED?

For those whose interest is leading A-level climbs, during the course of the program you’ll help a climb leader run a BCEP group and assist on at least three climbs. For those whose interest is higher-level climbs, you’ll be expected to participate to a higher degree in the running of a BCEP group, teach at least three field sessions of Intermediate Climb School (or Advanced Rock, Steep Snow and Ice, or an equivalent skill-builder), and assist on at least three climbs. In all of these, you’ll be evaluated and given ideas for improvement or alternative methods. SOUNDS GOOD, HOW DO I GET INTO THE PROGRAM?

We ask that you send your application and climbing resume to LeadershipDevelopment@mazamas.org, and have three climb leaders send in recommendations for you to the same email address. The recommendations help us to understand what 12 MAZAMAS

climbing, social, and/or leadership skills people are already seeing in you. The climbing resume is so that we understand the climbing experience level you’re coming into the program with—we ask for not just what route and mountain, but also the type of climb (Mazama, private, or guided) and your role in it (participant, assistant, or leader), and whether or not it was successful (some people include notes as to what stymied unsuccessful summit climbs). The “resume” should also contain any sort of outdoor education or type of activities you’ve done, any sort of medical training you’ve had, and any Mazama volunteering that you’ve done. If you want to lead A-level climbs, we are looking for you to have done on the order of 12 alpine climbs (half of which have been Mazama climbs), and if you’re looking to lead B or C (or higher level) climbs, for you to have done on the order of 16 alpine climbs (half of which have been Mazama climbs). Talk to us if there are issues with the requirements but you’re still interested in the program. The application helps us understand what your goals are in becoming a climb leader. We ask that you consider the following questions when you apply: ■ What motivates you to apply to this program? ■ What do you hope to get out of the program? ■ What aspects of being a climb leader interest you? ■ What do you plan on doing as a climb leader? We have about 45 people in the Leadership Development program, and around another 20 folks who are Provisional Leaders. We don’t have a limit on the number of people who can join. The whole program is expected to take about three years so that you can mature through the program. Many people try to rush through it in a year (which was my initial thought when I first joined), but there is a maturity that takes place as you focus on what it means to lead others either in the teaching field or on a climb. We hope that it’s a road you’d like to travel—if you do, please get in touch!

MAZAMA FIRST AID COMMITTEE HAVE YOU THOUGHT ABOUT BECOMING A WILDERNESS FIRST AID (WFA) INSTRUCTOR?

VOLUNTEER OPPORTUNITIES

mazamas.org/volunteer

CARDIO PULMONARY RESUSCITATION (CPR) INSTRUCTOR NEEDED! The Mazama First Aid Committee is looking to add instructor(s) to our pool of CPR trainers. If you are a qualified, current CPR instructor and would like to teach American Heart Association (AHA) CPR and Hike Leader First Aid courses to Mazama members, please send an email to firstaid@mazamas.org. If you are not currently qualified as a CPR instructor and are interested in becoming qualified as an AHA instructor, please let us know about your interest. To learn more about Mazama CPR courses, visit mazamas.org/cpr.

FIRST AID COMMITTEE SEEKS NEW MEMBERS

The Mazama First Aid Committee is gauging interest to see if there are Mazama members who may be interested in becoming nationally-qualified WFA instructors. The Mazamas have partnered with Base Medical since 2020 to deliver WFA training to Mazama members. In 2020-2021, several Mazama members completed Base Medical instructor training and became nationally-qualified WFA instructors through Base Medical. Base Medical is considering conducting a WFA instructor qualification course in June 2022 for Mazama members. A minimum requirement to becoming a WFA instructor is a current Wilderness First Responder (WFR) or higher wilderness medicine qualification. If you are interested, please send an email to firstaid@ mazamas.org, and if there is enough interest we will let you know about the next steps.

The Mazama First Aid Committee is looking for new members. Tell us about yourself, your background (medical, project management, education), and any specific areas where you would like to help. We deliver over 26 course instances of CPR, Hike Leader First Aid, Wilderness First Aid, and Mountain First Aid to over 225 Mazama members annually. Contact firstaid@mazamas. org for more information.

CLIMBING COMMITTEE SEEKS NEW MEMBERS The Climbing Committee manages all aspects of the Mazama climbing program, from approving climbing education program content to setting the standards for climb leadership. The committee is also actively recruiting and training leaders in best practices while promoting and developing a robust schedule of climbing activities. Committee membership is reserved for full climb leaders and, by exception, provisional climb leaders and Leadership Development candidates. Only full climb leaders can hold voting positions. Additionally, we are looking to grow our “Friends of the Committee” ranks to include anyone who has an interest in helping with our climbing program. We are currently looking to fill the following roles: ■ Secretary: This role requires a full climb leader. The secretary is responsible for taking minutes, reviewing a backlog of minutes, and ensuring that minutes are approved and archived. This is a voting position and backs up the chair, among other duties. ■ Climb Leader Continuing Education Coordinator: This role involves scheduling and coordinating opportunities for climb leaders to keep their required certifications up to date. Examples are Avalanche and Crevasse Rescue recertifications. Additionally, this role would help with Climb Leader Update sessions. This position is open to anyone on a leadership track. ■ Awards & Recognition: This role involves processing and handling climbing awards, including coordinating an award ceremony. This position(s) is open to anyone interested. If you’re interested in volunteering in any of these roles, or have interest in other areas of the climbing program, please contact the chair at climbing@mazamas.org. MARCH/APRIL 2022 13

14 MAZAMAS

FAREWELL TO OREGON’S CENTRAL CASCADE GLACIERS? by Anders Eskil Carlson, Ph.D., Nicolas Bakken-French, and Erin K. Hennessy, Oregon Glaciers Institute

I

n 1939, Kenneth Phillips waxed whimsically in the closing of his Mazama Bulletin article Farewell to Sholes Glacier: “perhaps mountaineers of the fairly near future may look upon the empty cirques of Mt. Hood as a normal condition, much as climbers of today may pardonably consider those of Mt. McLoughlin.” Phillips was discussing the departure of Sholes Glacier from Mt. McLoughlin, the first glacier disappearance documented in Oregon, not knowing the remarkable prescience his poetic closing contained. A little over 80 years later, that “fairly near future” is the modern here and now, at least for the glaciers in the Oregon Central Cascades. GLACIER SURFACE MASS BALANCE

The Oregon Glacier Institute, with generous support from the Mazamas, had planned in 2021 to resume seasonal surface mass balance measurements on Collier Glacier on the northwest side of the North Sister volcano in the Oregon Central Cascades (above). Surface mass balance is the measurement of a glacier’s “ins” and “outs.” One measures the amount of summer melt using PVC pipes drilled

into the glacier’s surface (the outs; the term for glacier mass loss is ablation) and the amount of snow remaining at the end of the summer using snow pits (the ins; the term for glacier mass gain is accumulation). That end-of-summer snow is then slowly turned into firn (granular ice crystals) that eventually compacts into glacier ice. The snow-firn-ice metamorphosis takes many years.

Above: Photograph of Collier Glacier on September 25, 2021. The snow cover is from a mid-September snowfall that hides the bare ice of the entire glacier. Photograph by Nicolas Bakken-French.

Thus, in summer on a normal glacier, one would walk up the glacier on bare ice in the ablation zone. As the elevation increases, one crosses from bare ice onto last winter’s snow in the accumulation zone. Under that snow are many prior winters’ snows and then firn resting on glacier ice. The transition between the ablation and accumulation zones is called

continued on next page MARCH/APRIL 2022 15

Glaciers, continued from previous page

the equilibrium line and its altitude is equivalent to the elevation where the mean annual temperature is freezing (32 °F, 0°C). Another way to think of the equilibrium line is that it is also the end-of-summer snowline on the glacier. On a healthy glacier in equilibrium with climate, accumulation equals ablation. The mass of the prior winter’s snow remaining at the end of the summer above the equilibrium line is equal to the mass of ice melted during the summer below the equilibrium line. The ins match the outs and the glacier’s overall mass does not change. On most glaciers in equilibrium with climate, about 55 percent to 75 percent of the glacier’s area should be in the accumulation zone above the equilibrium line, with the range reflecting individual glacier geography, geometry, and climate. That is, at the end of the summer roughly two-thirds of the glacier should still have some snow cover from the prior winter. On an unhealthy glacier, the accumulation zone is consistently less than two-thirds of the glacier area. And to kill off a glacier, the equilibrium line must rise due to a warming climate so that it is higher than the upper reaches of the glacier and the glacier has no accumulation zone. The glacier is now starving and will cease to flow once it has lost so much ice that it is no longer 100 feet (30 meters) thick, the threshold thickness for ice to deform under its own weight. Surface mass balance measurements are critical for documenting how seasonal weather drives long-term changes in climate and glaciers. If a glacier retreats, was it due to warmer summers causing more melt? Or has there been less snowfall? Or a combination of the two? Without such measurements, one is left with just speculation on what is driving glacier changes. At present, only glaciers in Alaska, Washington, and Montana have surface mass balance measurements conducted on a seasonal to annual basis, leaving the glaciers of Oregon, California, Wyoming, and Colorado unmonitored (the lone glaciers of Utah and Nevada are most likely gone). Professor Peter Clark and his students at Oregon State University made surface mass balance measurements on Collier Glacier in the late 1980s into the mid16 MAZAMAS

Figure 2. Accumulation area ratio of Collier Glacier (top) and nearby summer temperature (bottom). Top: accumulation area as percent of total glacier area. Dashed line indicates equilibrium ratio of 70 percent: above 70 percent is a positive mass balance year; below 70 percent is a negative mass balance year. Pink are data from satellite observations; red are data from surface mass balance measurements. Bottom: McKenzie Pass summer (June, July, August) temperature in blue. Dashed line is average temperature of 1990s. 1990s with one more set of measurements made in 2009–2010. These measurements indicated that Collier had to have an accumulation zone ratio of 70 percent to be in equilibrium with climate. However, the consistent measurements were abandoned due to lack of support from the State of Oregon. Despite the incontrovertible evidence of global warming and its impact on glaciers, as of 2021 the State of Oregon still shows no interest in documenting, monitoring, or understanding the retreat of Oregon glaciers and their attendant consequences to the environment and water resources of the state. For instance, the frequent state climate assessments never mention Oregon’s glaciers and their changes; the state’s 100-Year Water Vision makes no acknowledgment of glaciers’ roles in the hydrologic cycle. Research support from groups like the Mazamas is therefore critical to make up for our government’s neglect of their constitutional duty to protect our environmental trust. Indeed, the Mazamas maintained surface mass balance measurements on Mt. Hood’s Eliot Glacier from the 1960s up to the

mid-1980s, showing the organization’s commitment to glacier science. COLLIER GLACIER IN 2021

We headed out in mid-September to scout Collier Glacier. We planned to determine proper locations for the PVC melt stakes on the glacier and return in a week to install the stakes. Instead of the normal glacier profile described above, what we found halted our work in its tracks. As I mentioned, a hot summer can drive glacier retreat through increased melting and consequently more outs than ins. That heat also melts the snow and thus reduces the ins. Oregon had experienced an unprecedented heatwave a month and a half earlier in late June to early July, which the World Weather Attribution group found to have a 1-in-1000 chance of occurring, with grater than 99 percent of the heatwave due to human greenhouse gas emissions. In addition to its unprecedented nature, the heatwave was also devastating to Oregon’s glaciers and snowpack. While a

dusting of new September snow lay over Collier Glacier signaling with large accumulation zones and the glacier gained net mass. winter’s encroachment, the heatwave had not only melted ice Nevertheless, three out of the last five years were bad to abysmal. in the ablation zone, but also all the prior winter’s snow in the We then compared the last five years against the Collier accumulation zone, leaving the glacier in a state of starvation. surface mass balance record from the early 1990s (Figure 2). Collier Glacier had no accumulation zone for the 2020–2021 water For 1990–1994, Collier Glacier had an accumulation zone that year (a water year begins October 1 and ends September 30). covered about two-thirds (1990, 1991) to 80 percent of the glacier Without an accumulation zone, Collier Glacier lost mass at (1993). Two other years had negative surface mass balances, with every elevation for the 2020–2021 water year. With such drastic accumulation areas of around 50 percent (1992) to 35 percent conditions, we decided against installing the surface mass (1994). The one-off 2010 year measurements indicated that Collier balance equipment on the glacier as the lack of an accumulation had about 75 percent of the glacier in the accumulation zone. zone violates basic assumptions that go into the technique. The equilibrium line altitude was above the glacier’s highest reaches—8,920 feet above sea level. At its 1990s extent, the equilibrium line altitude on Collier Glacier should be at about 8,050 feet above sea level for the glacier to have 70 percent of its area in the accumulation zone. The temperature of 2021 over Collier Glacier was therefore quite extreme to drive the end-ofsummer snowline more than 900 feet higher than where it would typically reside in a climate that would sustain the glacier. We therefore switched focus and used the Mazama financial support to investigate the extent of the accumulation area on Collier for the last five years with satellite imagery to place the 2021 summer in historical context. Figure 2 shows the accumulation area record for Head of Collier Glacier on September 2, 2020, showing only about 1 foot of snow remaining Collier Glacier. At present, Collier from the prior winter. Photograph by Anders Carlson. Glacier is about 110 football fields in area. Remember that for Collier to be in equilibrium, about 70 This limited record points toward the 2017 and 2019 years for percent of its area should be in the accumulation zone, or around Collier being nothing out of the normal while also highlighting the 75 football fields of snow remaining at the end of the summer. severely negative 2018 year (nine percent accumulation area ratio) However, Collier Glacier lacked an accumulation zone in 2021 (0 and extremely negative 2020 and 2021 years as unprecedented. percent ratio). When we visited Collier Glacier on September 7, EXTREME SUMMERS 2020, we found only about a foot of snow remaining on the upper While Collier Glacier did not have an accumulation zone in reaches of the glacier (above). It did not snow on the glacier until 2020 and 2021, an additional phenomenon occurred in 2021: The mid-October of 2020, making for a long summer. By mid-October, heatwave melted through all the prior winter’s snow and into the all the snow on Collier was melted away and the glacier had an pre-2020 snow/firn that had accumulated. Those snow gains of accumulation zone ratio of 0 percent in 2020 as well as in 2021. In 2019 and 2017, along with the little snow of 2018, were obliterated, 2019, the accumulation zone was 85 football fields in size (a ratio leaving an entire glacier the size of 110 football fields of bare of 78 percent), marking a positive mass balance year for Collier. ice. One analogy to this phenomenon is a political prisoner on However, 2018 was another bad year with an accumulation zone a two-week hunger strike being forced by the guards to undergo covering only about 8 percent of the glacier (nine football fields). liposuction to hasten a morbid end to the hunger strike. Conversely, 2017 was another healthy year with an accumulation The year 2021 is not the only extreme summer we have zone of 97 football fields (88 percent ratio). In summary, two of the experienced in recent memory. There is 2015. Until 2021, 2015 last five summers had significant melting with no accumulation was the hottest summer on record that followed the lowest endzone: 2021 and 2020. In addition, 2018 had an accumulation of-winter snowpack on record, which set up dire conditions for zone that covered less than 10 percent of Collier Glacier. In fact, Oregon’s glaciers. In fact, the summer (June, July, August) average we would be shocked by the 2018 year if it wasn’t for how much worse 2020 and 2021 were. In contrast, 2017 and 2019 were years continued on next page MARCH/APRIL 2022 17

Glaciers, continued from previous page

temperature at the nearest weather station to Collier Glacier, McKenzie Pass, recorded equal average summer temperatures for 2015 and 2021: 57.3°F (bottom of Figure 2). For comparison, the average summer temperature in the 1990s at McKenzie Pass was 52.2° (bottom of Figure 2). We find on many glaciers in the Central Oregon Cascades evidence of that 2015 year. In the summer of 2020, only three to four layers of snow rested above bare glacial ice on some Oregon Central Cascade glaciers. The photo to the right shows three of these snow layers on Crook Glacier on Broken Top. These snow layers above glacial ice indicate that the 2015 summer melted away the The accumulation zone of Crook Glacier on Broken Top on August 28, 2020. Only three pre-2015 accumulated snow and firn, just like years of snow are visible above bare glacier ice, showing the loss of all prior years’ the 2021 heatwave wiped out the post-2015 accumulation during the summer of 2015. Photograph by Anders Carlson. accumulated snow on Collier. Thus, one hot of global warming, that 2021 heatwave had a 1-in-1000 chance of summer can remove the positive mass gains from prior cooler occurring, which would have been 150 times rarer if not for that summers and/or snowier winters. +1.2°C of global warming. At +2.0°C (+3.6°F) of global warming, Another force multiplier from these hot summers is the which we will likely surpass even with global nations’ current change in the glacier’s reflectance: the glacier’s albedo. Albedo is carbon emission pledges, the heatwave is estimated to occur every a measure of how much of the sun’s energy (shortwave radiation five to 10 years. Human greenhouse gas emissions have taken the called insolation) is reflected versus absorbed by a surface. 2021 heatwave from being a 1-in-150,000-year event to a 1-inAn albedo of 1.0 would reflect all insolation. Snow has a very 1000-year event, and will make it a less than 1-in-10-year event in high albedo around 0.8–0.9, which explains why one burns the the coming decades if we do not change our collective behaviors underside of one’s nose on a blue bird powder day despite wearing starting at the top and fully divest the United States from fossil fuel a billed cap and temperatures well below freezing. That high use. What we are doing now and are planning to do in the future albedo snow reflects the insolation back upwards where it then is clearly not enough to keep Oregon as the Oregon we know and burns one’s nostrils. Old snow/firn has a lower albedo of around love. 0.6. Glacier ice absorbs even more insolation with an albedo of The fact that three out of the last five summers were extremely 0.4–0.5 These differences are apparent in the photo above where bad for the health of Collier Glacier shows that even +1.2°C of the older snow layers and the glacier ice itself are darker than the global warming at 416 parts per million carbon dioxide in the 2020 snow layer. atmosphere is too much. Reducing carbon dioxide levels to below Absorbed versus reflected insolation matters. Just think 350 ppm (the level in the 1980s) would return Oregon back to a about running from the car to the swimming pool as a kid. While time when glaciers were more or less happy with their winter sprinting on the parking lot blacktop, one’s feet burn like the snowfall and summer temperatures. The Mazama surface mass dickens with the heat abating somewhat once one can hop onto balance measurements for Eliot Glacier on Mt. Hood documented a cooler cement sidewalk. The blacktop has a lower albedo than slight glacier growth between 1963 and 1983, meaning that the the lime-gray cement and absorbs more insolation that then burns climate of the early 1980s could sustain glaciers near to what the one’s feet more than the higher albedo cement. U.S. Geological Survey depicts on their maps. We could bring the Burned-feet childhood memories aside, heatwaves can switch landscape back into accord with the maps, saving the federal how reflective a glacier’s surface is. A heatwave removes the highly government much time and money in updating the physical reflective snow surface, burns through the less-reflective old snow geography of the maps! and firn to expose the low albedo, absorptive glacial ice. A snow/ Nevertheless, the climate that will result in Kenneth Phillips’ firn-free glacier now melts even more thanks to the hot summer vision of “empty cirques” may already be here, at least for and change in the glacier’s albedo that absorbs more of the sun’s Oregon’s Three Sisters Wilderness. The carbon dioxide level in energy. The heat switched the glacier from being cement to the atmosphere may be already too high to sustain glaciers in the asphalt. central part of the Oregon Cascades. There are some good snow LOOKING FORWARD years with positive mass balances, but the bad years are really bad Unfortunately, unless humans immediately cease to emit and growing ever worse. greenhouse gases AND start to reduce the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere from the current 412 parts per million level towards a sustainable target below 350 parts per million, glaciers will soon cease to exist in Oregon. At the 2021 level +1.2°C (+2.2°F) 18 MAZAMAS

BACKCOUNTRY SKI LEADER PROFILE: MIKE MYERS What do you love about skiing in the backcountry? Skinning on low-risk terrain allows my mind to drift between awareness and random thoughts (I wonder what fish look like at the bottom of Crater Lake?), or alternatively be engaged in friendly conversation without distraction. On the flip side, navigating complex terrain on the way up or down requires heightened awareness and concentration—life, work, and other distractions have to be set aside to focus on the task at hand. Do you have a favorite place to tour? Mt. Rainier is a go-to favorite if the gate is open. Depending on the avalanche risk, Nisqually Chutes, Camp Muir, Mazama Ridge, or the Tatoosh Range can be in play. What’s a memorable moment from your time skiing in the backcountry? When down in Argentina on a hut trip, our first run was down a 45-degree slope with our 55-pound packs. It reminded me that you need to be prepared to ski anything at any time in the backcountry. How should someone with no backcountry experience get started in the sport? Mazama classes are a great intro, especially since they help establish a community and mentorship to grow into the sport. Not to be discounted is making sure you have the alpine skiing skills prior to getting into the backcountry. Take some ski lessons if needed. Ideally, you should be able to ski all of Heather Canyon before venturing out into the backcountry. What’s a good place for people who have taken an Avalanche Awareness course to get out on the snow? Palmer at Timberline is a good place to practice skinning, transitioning, and skiing on your backcountry gear. Also on Mt. Hood, Bennet Pass and White River are low-angle alternatives that get you away from the resort.

Mike Myers, Backcountry Ski Touring Committee member and ski tour leader

Handcrafted custom framing + photo printing

Is there a tip or trick you often come back to when out skiing? I love using B&D ski leashes, as you don’t have to worry about a ski getting away from you at the top of Mount St. Helens, or losing it in deep snow. They’re also breakaway in case there’s an avalanche. What’s your favorite piece of touring gear? Or a favorite snack? Outdoor Research makes an insulated hat with ear flaps that is great for the uptrack and regulating heat—and it’s only around $20. Is there anything else that comes to mind you’d like to share with fellow Mazamas and the outdoor community? Just be kind, share information, and be helpful to those on the skin track. The backcountry is not time for bro-ing out. Share pit test info, help cut trail, spread the snacks and the stoke. Try and end each tour having learned or shared something.

Hazel Dell pnwframing.com

7720 NE Hwy 99, Suite E. Vancouver, WA 98665 360.693.0720 MARCH/APRIL 2022 19

MUSICAL MOUNTAINEERS

Above: the Musical Mountaineers play near Mt. Rainier. Photo by Rose Freeman.

by Claire Tenschar

M

ost Mazamas would admit to hearing the figurative music of the mountains, but what about literal music? Imagine hiking up a to a glacial tarn and hearing the sounds of a duet, played not over a Bluetooth speaker but performed live on a four foot digital piano and a violin. Anastasia Allison and Rose Freeman are the Musical Mountaineers, and you just might run into them in the Pacific Northwest.

They’ve performed on the summit of Sauk Mountain, in deep cascade snow, and on the flanks of Mt. Rainier. Their hikes can be extreme, especially when you consider they are both carrying instruments, both women are mountaineers and climbers. For their Musical Mountaineer ventures they generally hike 8-10 miles round trip, and as you can guess from their name they are usually going uphill, sometimes as much as 4,000,m feet. Occasionally they will switch things up, a particularly lovely video from two years ago has Allison covering “Pure Imagination” as the sun sets over the mountains and Freeman skates on a frozen tarn, it’s a duet for skate and piano. Their 20 MAZAMAS

music ranges from classical improvisation, to hymns, and covers of modern songs like the Jurassic Park theme. Each song is inspired by the specific destination. They treat each hike as a concert, from dressing the part in floor length, elegant dresses, to filming from multiple angles. Conversely, they still treat each hike with respect, noting they always carry the 10 essentials. Some of the challenges to playing outdoors and at altitude include strings that go out of tune due to cold air, frozen fingers, high winds that rip at their dresses, and bugs. Many of their concert videos show them wearing thick down jackets. Sometimes in their winter videos

you can see Freeman’s piano shut down due to the cold, but she gracefully turns it back on and continues playing. Both women were introduced to music by their grandparents, and music was a thread throughout their early life and schooling. Allison, the violinist, explored many careers including state park ranger, adventure guide, and outdoor clothing designer. As a ranger she would patrol the campground playing hymns and fiddle songs with her violin to encourage her campers to have peaceful evenings. But she always believed that music couldn’t be her career. She thought she would have to give things up if she was to pursue music full

Above: the Musical Mountaineers in the high alpine. Left: Heading out for a gig. Photos by Rose Freeman.

time. After a near death experience in a car crash she says, “It got to the point where it was scarier not to do what I love.” Freeman is a music teacher who has her own piano studio. For years she suffered terrible migraines, and she credits the outdoors as a great source of relief from physical and mental ailments. Since childhood she dreamed of playing her piano on a mountain summit. When the two met as adults, “it felt like a lightningbolt moment,” according to Allison. They were on similar paths simultaneously. Each required a partner to help them see it was possible. To make the dream real, Freeman carries a 13 pound battery powered Yamaha keyboard in a pack with a total weight of 45lbs. Allison has a special violin for their outings. Part of the joy they derive from their performance is the physical

effort required. On their website they are clear that they consider themselves normal, regular people who decided to do something to bring joy to the world and they want their listeners to be inspired to do whatever we can imagine. Freeman and Allison are driven by the idea that we can all bring our own “music” into the world and make it a better place. They perform to remind viewers of the good that exists in the world. For all the complications of packing and planning for their outdoor concerts, Allison says it’s actually simple, this is how they connect with others in a meaningful way and share something positive. A Musical Mountaineers sighting is rare—akin to seeing Sasquatch. They don’t announce their outings, to respect Leave no Trace ethics. While they welcome you to say hi if you do see them in person, they hike very early in the morning using headlamps, aiming to perform at sunrise before most hikers are on the trail, both

because it is beautiful, and because they know not everyone wants to hear music in the wilderness. Most sightings are after the Musical Mountaineers have finished their performance and are headed down the mountain. The best way to find them is on Youtube, search for The Musical Mountaineers. Their latest video was a tiny boat concert.

MARCH/APRIL 2022 21

CLIMB LEADER PROFILE: GUY WETTSTEIN Residence: Wilsonville, OR Hometown: San Francisco What did you want to be when you grew up? A lineman for the county. Any hobbies or interests unrelated to hiking or climbing? Music. I’ve played bass and guitar in bands since high school, at least until I started climbing. What are people surprised to learn about you? I have a crush on Ryan Reynolds. What got you started climbing? I read Into Thin Air and developed a fascination with mountaineering. Fifteen years later I decided to take BCEP. When and how did you become involved with the Mazamas? I didn’t want my BCEP experience to end, so volunteering with the Mazamas was the best way to keep the dream alive. What was your path to becoming a climb leader? I was impressed with how supportive and nurturing my climbing mentors were and thought maybe I could do that someday. After I was recommended for leadership coming out of ICS, I felt confident enough to give it a go.

Guy Wettstein, Climb Committee Chair

Guiding principle or philosophy for leading? Find a strength in each member of the team and then value them.

Most treasured possession? My ‘96 Takamine EF440C acoustic guitar.

Because it’s there, because it’s fun, because it’s hard, or just because? Because all of those and more. I think it’s the process of climbing that I enjoy most.

Favorite book(s) or movie(s)? The Shawshank Redemption.

What is your favorite climb? Unicorn Peak is a nice little climb that puts it all together.

What are you reading now? Just finished up Let My People Go Surfing: The Education of a Reluctant Businessman, by Yvonne Chouinard

Best climbing memory? Leading Shuksan this past summer was pretty special and absolutely beautiful. Proudest moment in climbing? First Mt. Hood summit, obviously. Monkey Face was also a big deal for me. Best Type 2 fun experience (miserable at the time, fun in retrospect)? Rainout on Mount St. Helens. I haven’t been that wet swimming! What are your climbing goals for 2022 and beyond? I’m taking Advanced Rock in the spring. I’d like to lead a few more of the 16 peaks and we have a family trip to Italy where I plan to get a few days climbing in the Dolomites. Favorite piece of gear? My Patagonia R1 (jacket). 22 MAZAMAS

Favorite book or movie about climbing or the Northwest? Nordwand.

Favorite music? As a musician, I really dig on almost everything. I go through various listening phases, though. Pet peeves? Crumbs on the counter. People taking food off my plate without asking. How much more space do I have here? Person, living or dead, you are most interested in meeting? Anthony Bourdain. Occupation? Application Engineer at Siemens.

HIKING WITH ATHENA By Leigh Schwarz and Jay Feldman

W

ho doesn’t like hiking in a beautiful place on a gorgeous day with your best friend? Dogs love walks, and new places with new smells bring JOY! With many dog hike miles under our boots and paws, we can share what works for us.

The point of hiking with our dog Athena is for all of us to get outside for exercise, fresh air, and fun. Of course, we need to be in similar shape, or we need to pick a distance, elevation gain, and pace that works for all of us. Less crowded trails are more enjoyable than crowded ones, and very narrow trails can be stressful if we will meet others on the trail. Knowing Athena wants to be with us and is not inclined to run off is really important. We know flirtatious dogs, either with other dogs or people, but our little rescue is fearful. Until proven otherwise, she prefers to keep her distance from others, and we know she appreciates our help doing that. When she gets together with hiking friends—folks she knows—she is happy to be sociable and part of the group! But, even with friends, she does not jump

Above: Athena contemplating the Pacific Ocean at Ecola State Park. Photo by Leigh Schwarz.

up on people. We always connect her leash to a minimal harness which avoids choking and minimizes feet tangling in the leash. Connecting the handle of a soft, flexible leash to a carabiner on my pack allows me to let go periodically, knowing the leash is safely anchored to my pack. Occasionally, on a very lightly used trail— and if trail rules and conditions allow—we may hike with her offleash, but always leash her up when we see another dog. Water and snacks are musts for all of us. A small shallow plastic container is a perfect lightweight water bowl. Making sure we have enough water for all of us is critical. A quick-to-access plastic bag of small treats or kibbles makes giving little rewards easy and keeps

continued on next page MARCH/APRIL 2022 23

Athena, continued from previous page Athena’s attention on us. Bringing dog snacks for lunch breaks helps keep our friend from begging for lunch from us and other hikers. And keeping her leashed and close-by during lunch is essential for everyone’s comfort. Cold weather hiking, whether in snow or rainy conditions, takes more energy for all of us. Many dogs are happy to wear a jacket in the winter, especially when it’s wet. Athena and our two granddogs all like to wear their fleece-lined, rain-shedding jackets when it’s cold and wet. Some dogs hate booties and prefer their original equipment—pads and claws— for traction, but in snowy conditions we make sure Athena’s feet are free of ice clods. Sometimes she needs our help to remove them. Speaking of safety, our dogs, like all of us, can get injured. Being aware of some canine first aid is worthwhile. Don McCoy, a retired veterinarian, Mazama dog hike leader, and friend of ours, recommends the American Red Cross “Pet First Aid” app. We feel better prepared having spent time reviewing it. Of course, the app is no substitute for veterinary care. Poop. No dog article would be complete without mentioning it. We always carry plenty of dog bags and pay attention to be sure we properly address her poop. Having extra bags allows us to tie up the used bag and place it in a second bag before putting it in a designated backpack pocket for proper disposal later in a trash can. Scooping poop into a bag and leaving the bag on a trail or in the woods is unconscionable! Having a towel or two in the car for drying off a muddy dog before the drive benefits all of us. Then we head home, knowing we all had a good workout and shared a wonderful outdoor adventure. We love to hike with our dear pooch and she loves it too. Athena’s big grin tells all! The Mazamas lead dog-friendly hikes, usually once a month, in areas with wide trails and where dogs are required to be on a leash. Retired veterinarian Don McCoy often leads these hikes. Friends of the Gorge also hosts dog-friendly hikes.

Above top: Athena and Leigh at the top of Silver Star. Photo by Alex Beard. Bottom: Poop Fairy. Photo by Don McCoy. 24 MAZAMAS

A BRIEF HISTORY: MAZAMA SKI MOUNTAINEERING

by Richard (Dick) Iverson

T

he Mazamas have pursued various forms of ski mountaineering and backcountry ski touring for more than a century. According to Peggy Mills’ “Seventy Years of Mazama Skiing, 1897-1967,” the first Mazama ski mountaineering summit ascent/descent was of Mount St. Helens on May 27, 1950. It also seems likely that the Mazamas or other locals made ski descents from the summit of Mt. Hood prior to the oft-cited “first descent” by renowned Swiss skier Sylvain Saudan in 1971. Nonetheless, there appear to be few records of these individuals’ accomplishments, and before 1990 there was no official Mazama ski mountaineering class or program.

The development of a Mazama ski mountaineering class was the brainchild of former Mazama Don Adamski. Following a telemark ski race that was part of the 1989 State Games of Oregon Winter Edition, Adamski explained his vision to fellow race participants Jon Major and me while we enjoyed a beer or two on the deck of the Mt. Hood Meadows ski lodge. In the afterglow of fine skiing and refreshments, Don easily convinced us that such a class was a good idea. Adamski next obtained authorization from the Mazama Executive Council to assemble an ad hoc steering committee to help organize and launch a Ski Mountaineering (SkiMt) class as a pilot program. The committee consisted of Adamski as chair plus experienced ski mountaineers Leo Sattler, Mike McGarr, Dennis

Above: Former Mazama Ray Patrick leading the way down Mt. Adams’ Southwest Chutes, 1994. Photo by Dick Iverson.

Olmstead, and me. Our meetings also included John Courtney as a liaison to the extant Nordic Committee, which oversaw our activities and budget. The committee had many discussions about the class curriculum and implementation, and by early 1990 the first class was underway. Adamski and the other committee members served as instructors. I recall that the first class attracted only about eight students (others recall as many as 18), but regardless of the number, there was no lack of enthusiasm among the group. In those days most people skiing in the U.S. backcountry used skinny telemark skis with leather boots and either three-pin or cable bindings, and sharpening basic ski skills on ungroomed

continued on next page MARCH/APRIL 2022 25

Ski Mountaineering, continued from previous page snow was an essential part of the class. Spills and chills were common. Over the next several years, the SkiMt class began to mature, and in 1994 the Ski Mountaineering Committee gained full status in the Mazamas. The class size held relatively steady at about 30–35 students per year, but the curriculum evolved. There was a gradually increasing emphasis on safety and decreasing emphasis on teaching ski skills or advanced technical maneuvers—including rather comical attempts to teach groups of three or four people to ski downhill while roped together! Above: Longtime BCST tour leader Wei Self-arrest practice using only ordinary ski poles as braking devices Chiang riding his splitboard at Mt. Hood. Photo by Ali Gray. was more essential. Nonetheless, Right: Mazama ski mountaineering class members and instructors group pausing near the top of Mt. Adams’ Southwest Chutes to contemplate the descent were undeterred from skiing such objectives as Mt. Adams’ Southwest route, 1994. Photo by Dick Iverson. Chutes, which seven of us first accomplished on a Mazama climb led by Ray Patrick in 1994. Nowadays, the Southwest Chutes draw hordes of springtime skiers, but one rarely recent years, saw other skiers there in the early-to-mid 90s. the training By the late 1990s, ski mountaineering was evolving rapidly has included 24 hours of instruction, mostly outdoors on the snow, in North America, especially in response to the development and partly embedded in ski tours. No serious avalanche accident of modern alpine touring (AT) ski gear that was lighter, more has ever occurred during a SkiMt class activity or tour. reliable, and more forgiving than older gear. This change lured The fatal avalanche accident that occurred during a Mazama throngs of skilled downhill skiers into the backcountry at a rate Basic Climbing School graduation climb on Mt. Hood on May 31, that continues to grow today. Eventually, even some of us who 1998, had major impacts on the SkiMt program, however. It led were diehard telemarkers made the transition to AT gear (in to a redoubling of Mazama efforts to assess and mitigate risks, many cases in deference to aging knees). Snowboarding also and to new restrictions on the organization’s winter activities crept into the backcountry and into the SkiMt class. Prior to the above treeline. Combined with increasingly stringent Forest widespread availability of splitboards in the late 1990s, powderService regulations limiting group sizes within the Mt. Hood seeking backcountry snowboarders generally had to slog uphill on Wilderness Area, this signaled the demise of an early tradition in snowshoes, which was a deterrent for many. Today, backcountry which the Mazama SkiMt class culminated with a mass ski tour snowboarding is almost as common as skiing. to Illumination Saddle. Sometimes snow conditions on these Training in avalanche avoidance and victim rescue techniques wind-exposed winter tours made for tricky skiing, but I don’t recall has always been a key part of the Mazama SkiMt class. However, in anyone getting seriously hurt. 1990, the American Association of Avalanche Professionals—now Another early tradition of the SkiMt class was a springtime called the American Avalanche Association, or simply A3—hadn’t foray to Mount St. Helens. The outing wasn’t a formal part of the developed its well-articulated guidelines for avalanche safety class, but all students and instructors were welcome to participate classes aimed at backcountry travelers. Moreover, substantial at their own risk. (This activity predated the implementation of avalanche safety training that targeted recreationists was the current climbing permit and quota system at Mount St. Helens, difficult to find anywhere in the Pacific Northwest. For SkiMt, and springtime group size wasn’t an issue.) Sometimes a glorious we consequently assembled instructional materials from diverse ski descent from the Mount St. Helens summit was followed by an sources and created an avalanche safety curriculum that consisted equally glorious barbecue with abundant beverages and revelry. of a half-day lecture session at Timberline Lodge followed by a Many participants wisely camped onsite afterwards, rather than half-day on-snow session in Salmon River Canyon adjacent to making the drive home. the lodge. Over the years, Mazama SkiMt avalanche training has In the past two decades, Mazama ski climbs led by ski become more comprehensive and consistent with the evolving mountaineering participants have included descents not only of Level 1 Avalanche Fundamentals guidelines developed by A3. In Mount St. Helens and Mt. Adams but also South Sister, Middle 26 MAZAMAS

Above: Gear may change over the years, but the beaming smiles on a bluebird powder day never do. Photo by Ali Gray. Right: A group of BCST students on a tour at Mount St. Helens about a month before COVID-19 shut down the world. Photo by Ali Gray.